Use of scoring tools in municipal in-patient acute care services – a cross-sectional study

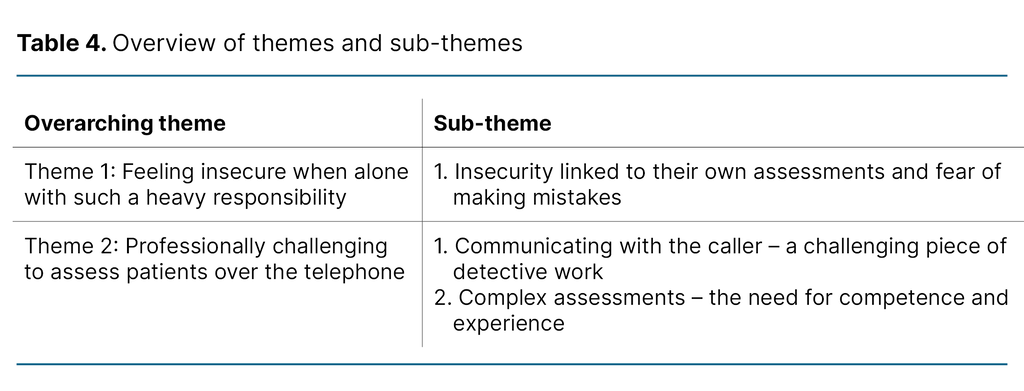

Introduction

The transfer of responsibility and tasks from the specialist health service to the primary health service means that more and more specialised municipal services must be established (1). Ensuring patient safety and quality in ever more complex municipal health services makes high demands of RNs’ clinical assessment and decision-making skills (2, 3).

Standardised scoring tools for early identification of exacerbation of somatic disorders and assessment of nutritional risk and risk of falls are recommended by health authorities at all levels of the health service, both nationally and internationally (4–7). The aim of the systematic use of scoring tools is to boost patient safety. They help create a common understanding in cooperation on patient care and provide a better basis for clinical decisions (8).

Systematic use of scoring tools in decision-making processes reduces the risk of inadequate assessments in clinical practice (9), helps confirm the intuition of experienced RNs in patient care (3, 10), and promotes accurate communication in cooperation with other health personnel (11). At an early stage, the Early Warning Score (EWS) tool can detect risks of somatic deterioration and death (12, 13).

The risk of undernutrition can be identified by the systematic use of nutritional risk scoring tools, and undernutrition can be prevented through the early initiation of nutritional treatment (14). Identification of fall risk may make health personnel and patients more alert to this risk, and serious injuries can be reduced by initiating individual and evidence-based interventions (15).

However, a number of studies emphasise that the use of scoring tools must always be adapted to the context. They must be used in combination with clinical judgement and should never be the sole decision-making basis (11, 16–19).

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain an overview of the use of clinical scoring tools in MIPAC services in Norway. We wanted to examine whether geographical region, organisation, location and structural factors led to differences in the use of scoring tools.

Background

The study sets focus on MIPAC services, an important measure in the Coordination Reform. The aim is to provide 24-hour emergency beds for acutely ill patients in order to reduce unnecessary hospitalisation (20).

Older patients and patients with chronic disorders and complex health challenges are an important target group. As these patients are in acute need of care, RNs must make rapid, precise and accurate clinical assessments and decisions in diverse situations (2, 3).

The law allows for MIPAC units to be freely organised in accordance with the local context, infrastructure and available resources in the individual municipality (21–23), leading to considerable variation nationally in the organisation of the services (24, 25).

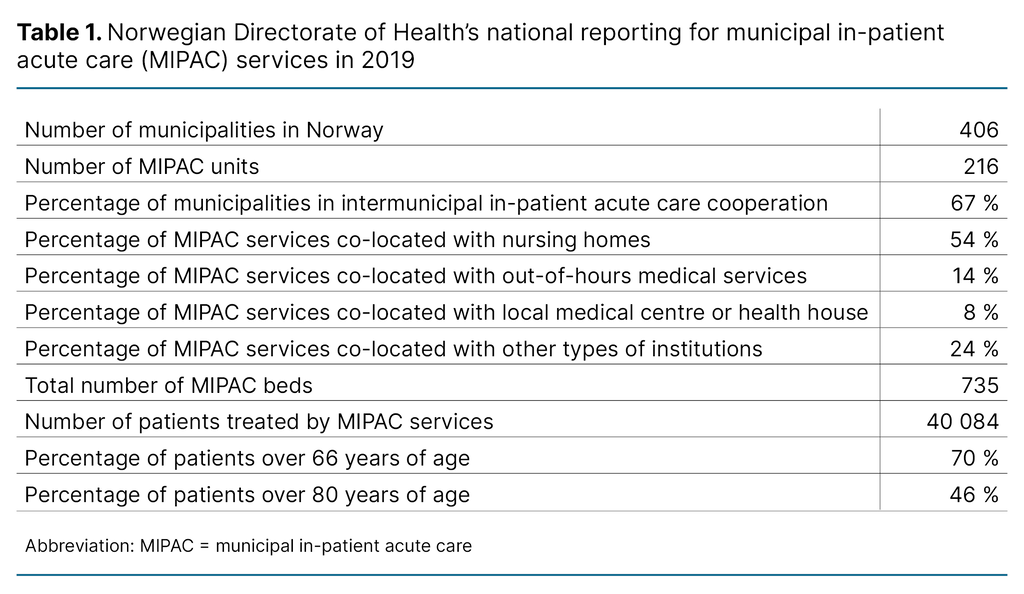

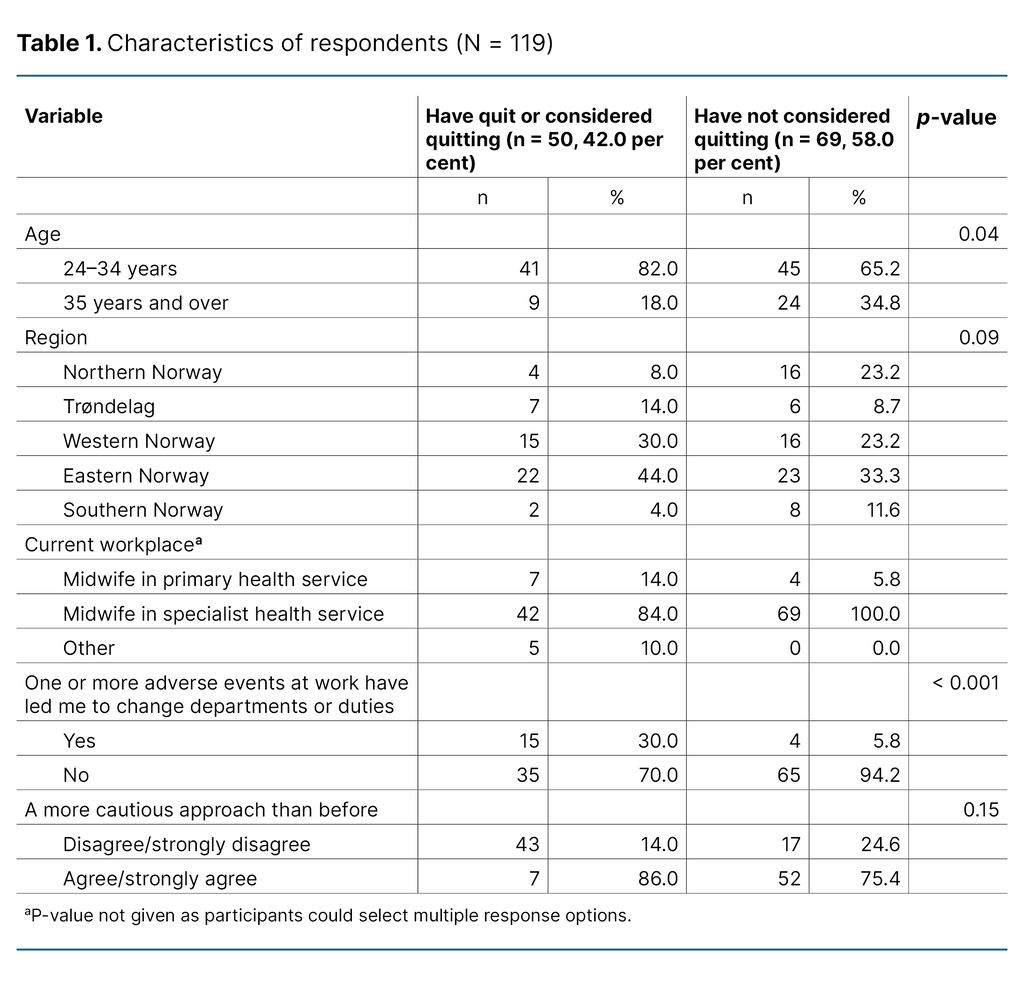

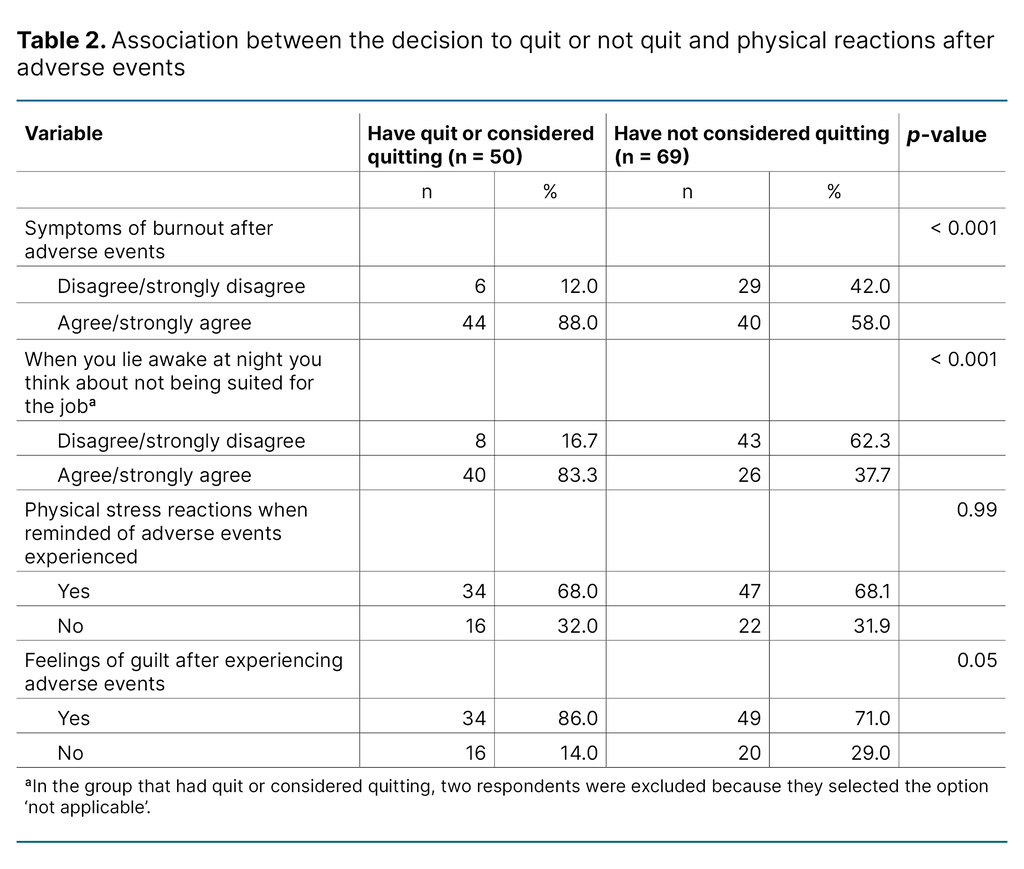

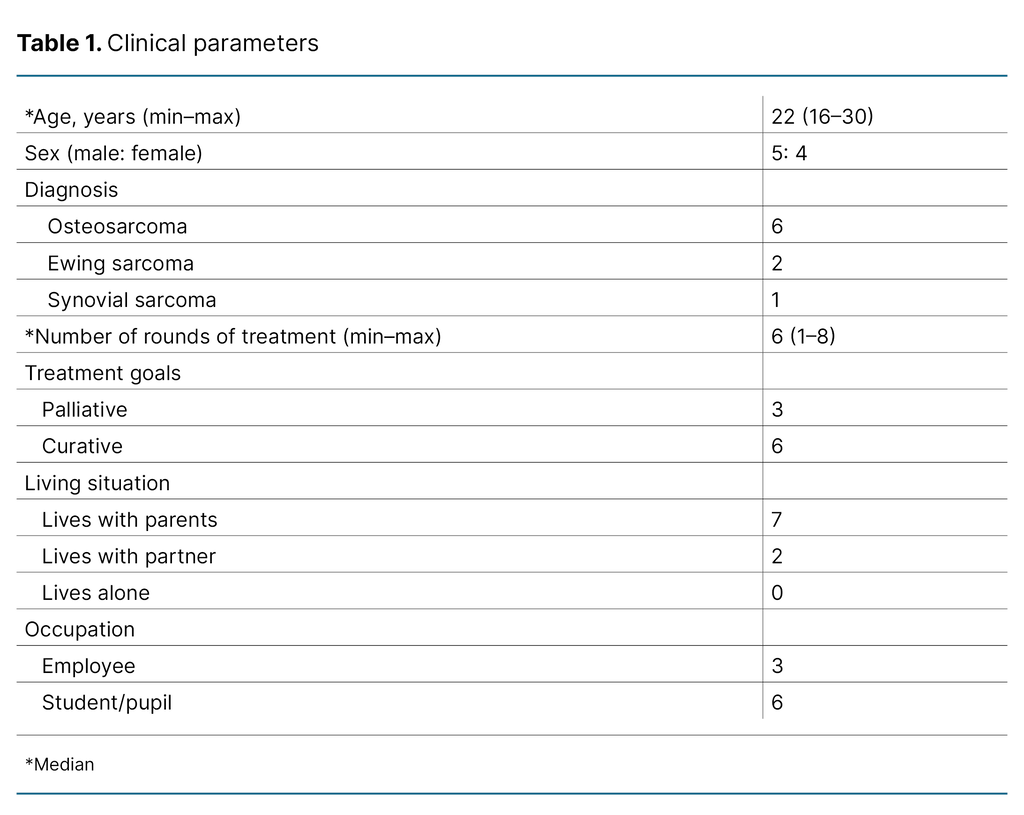

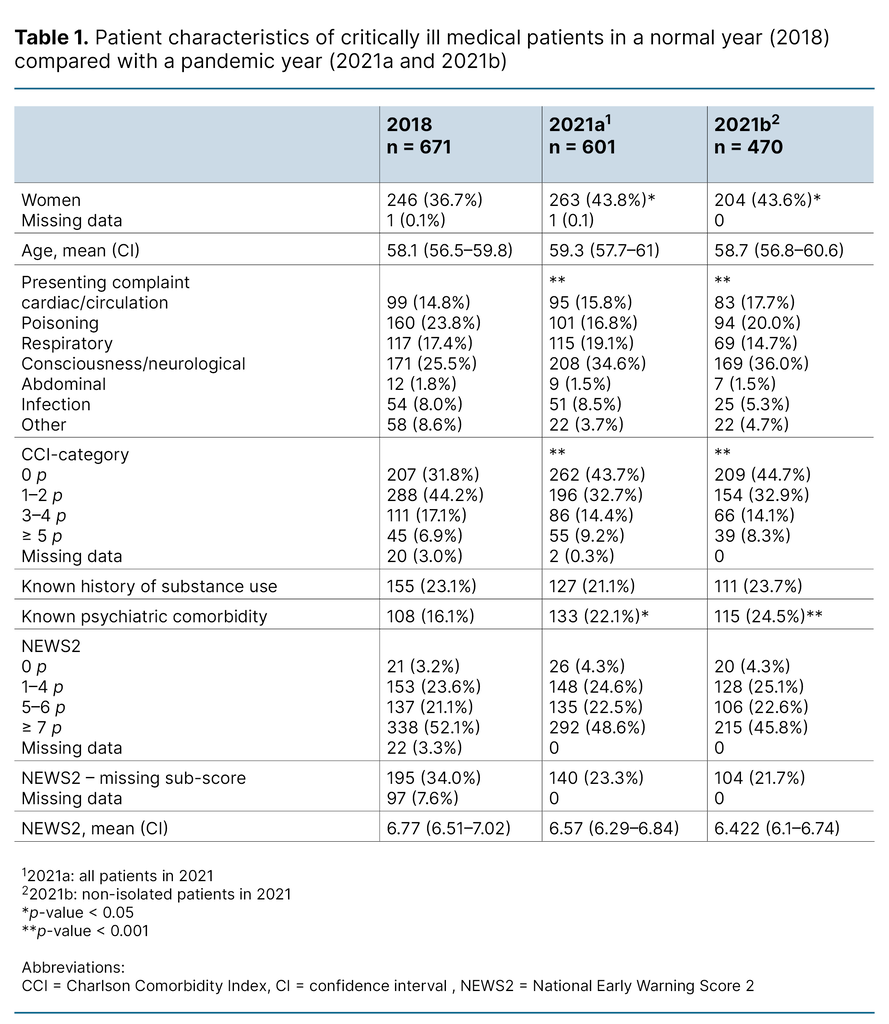

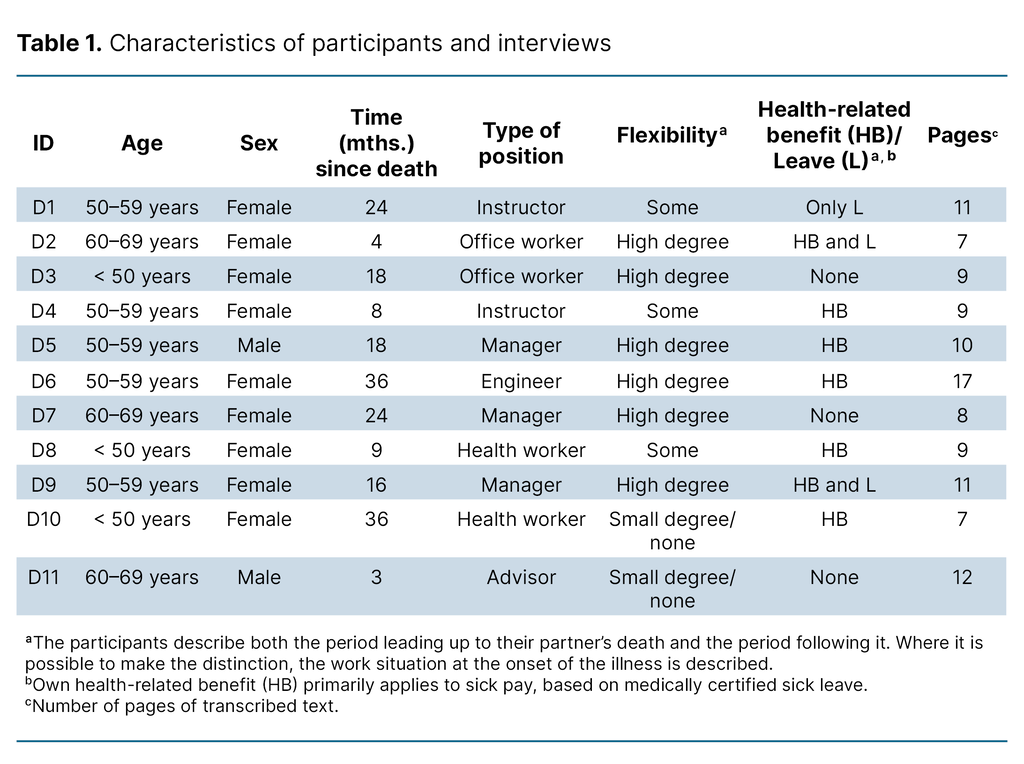

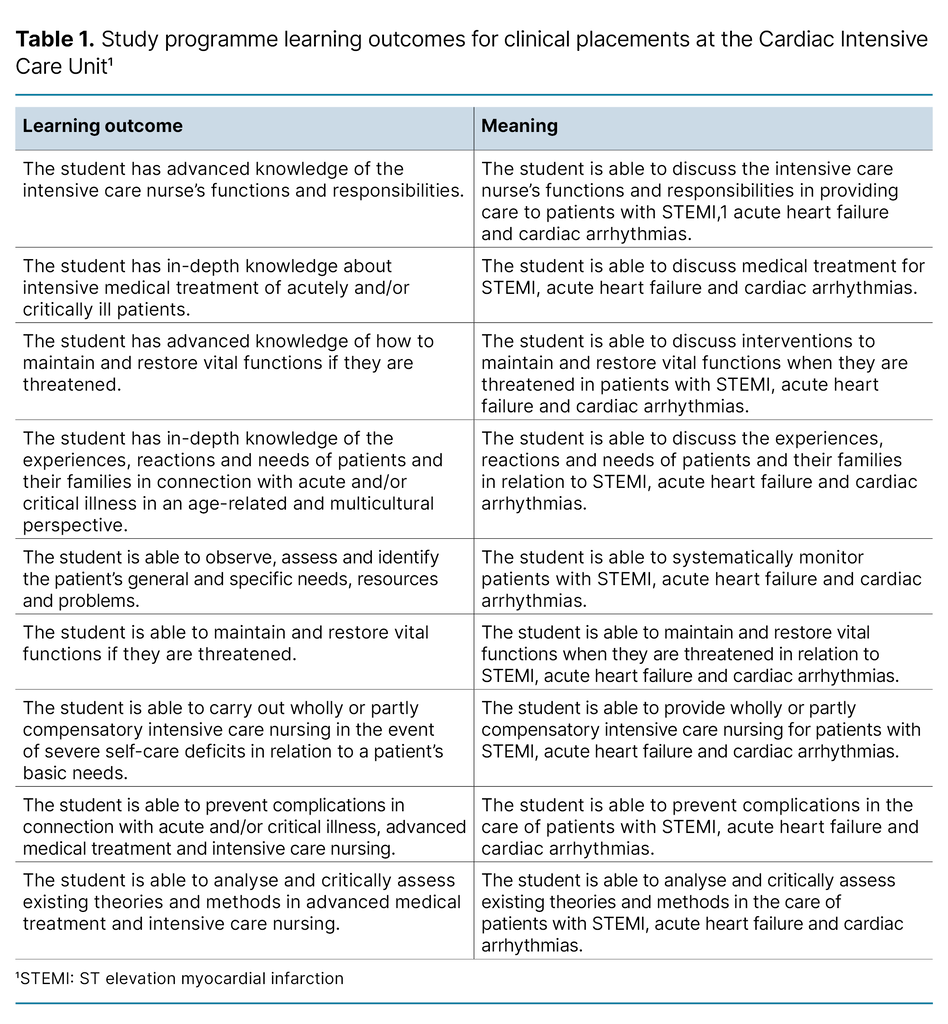

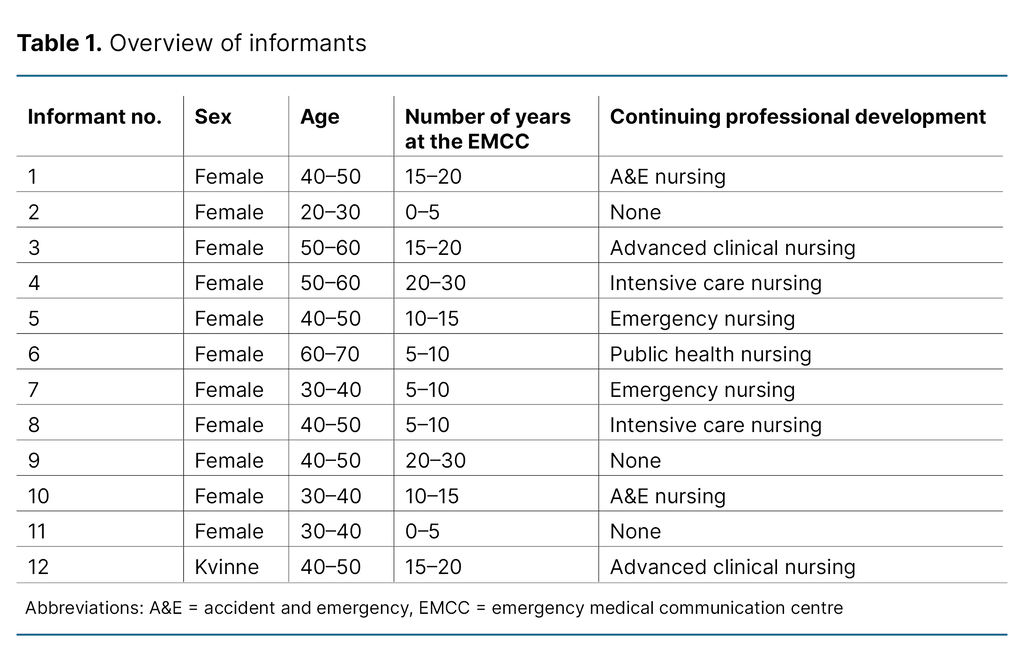

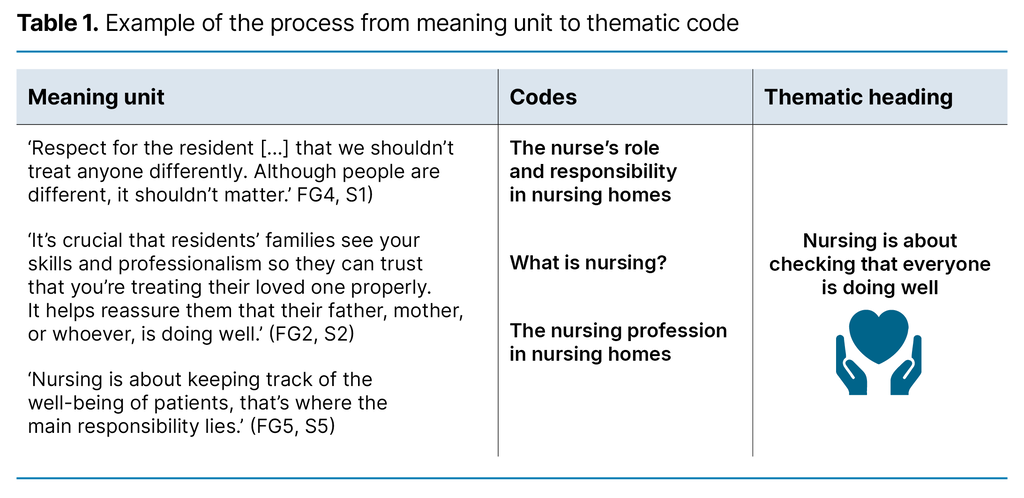

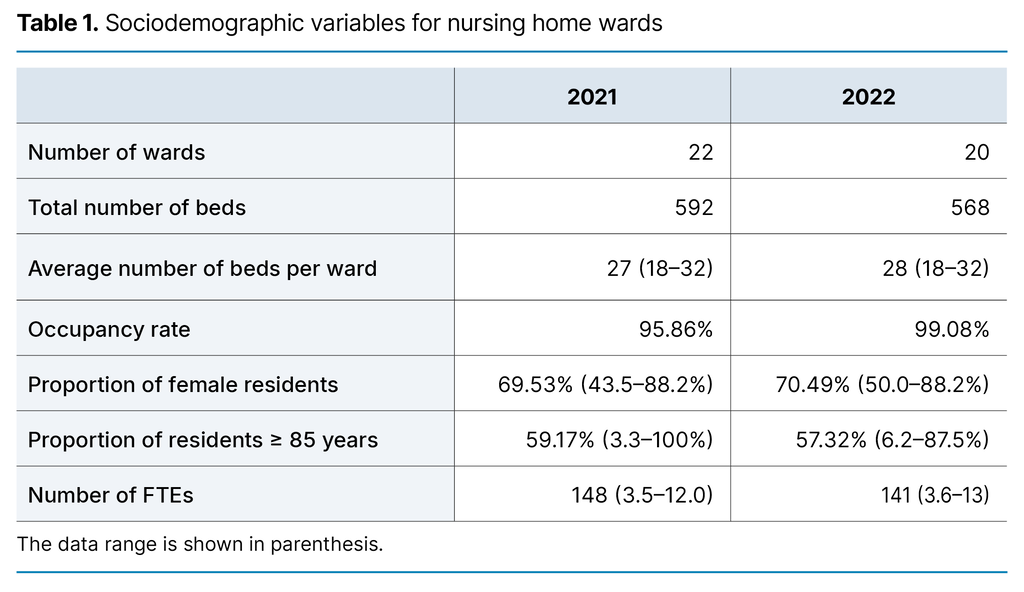

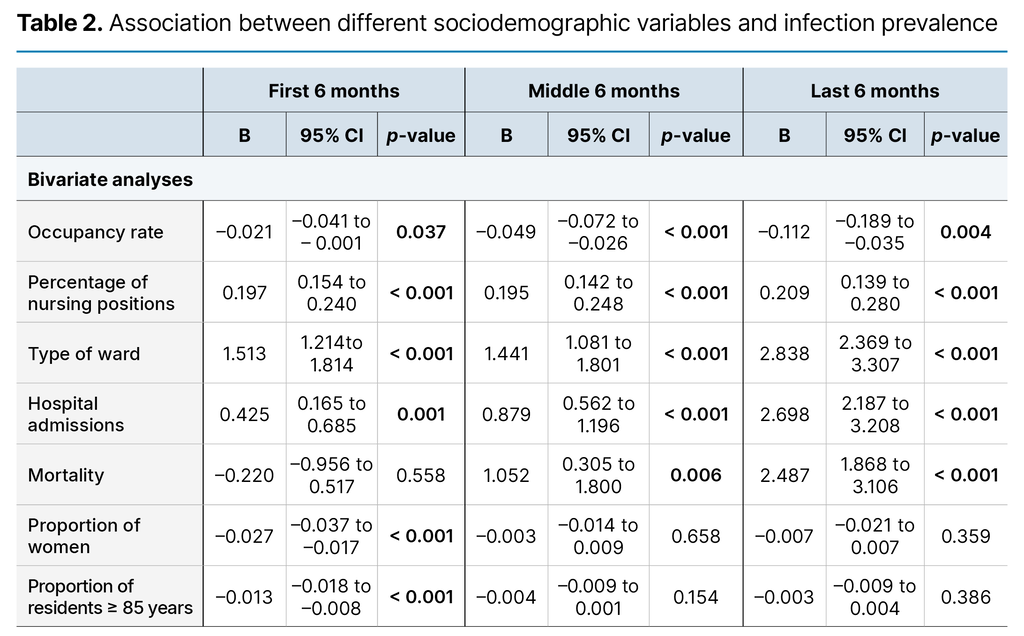

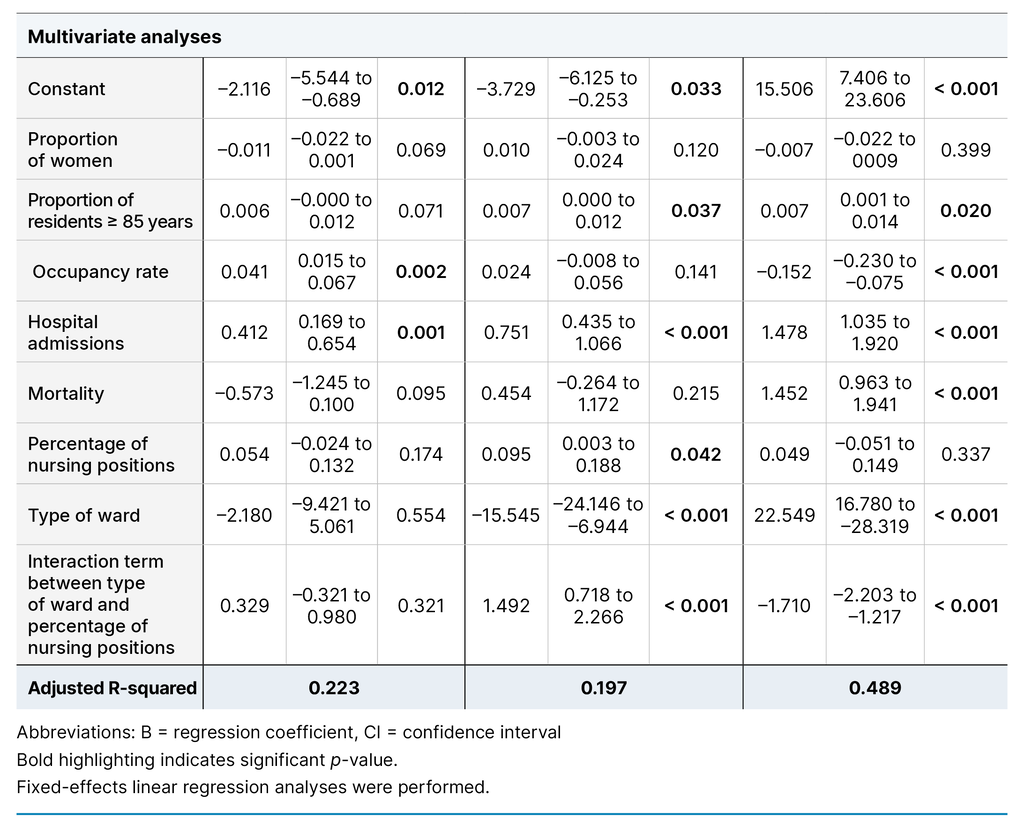

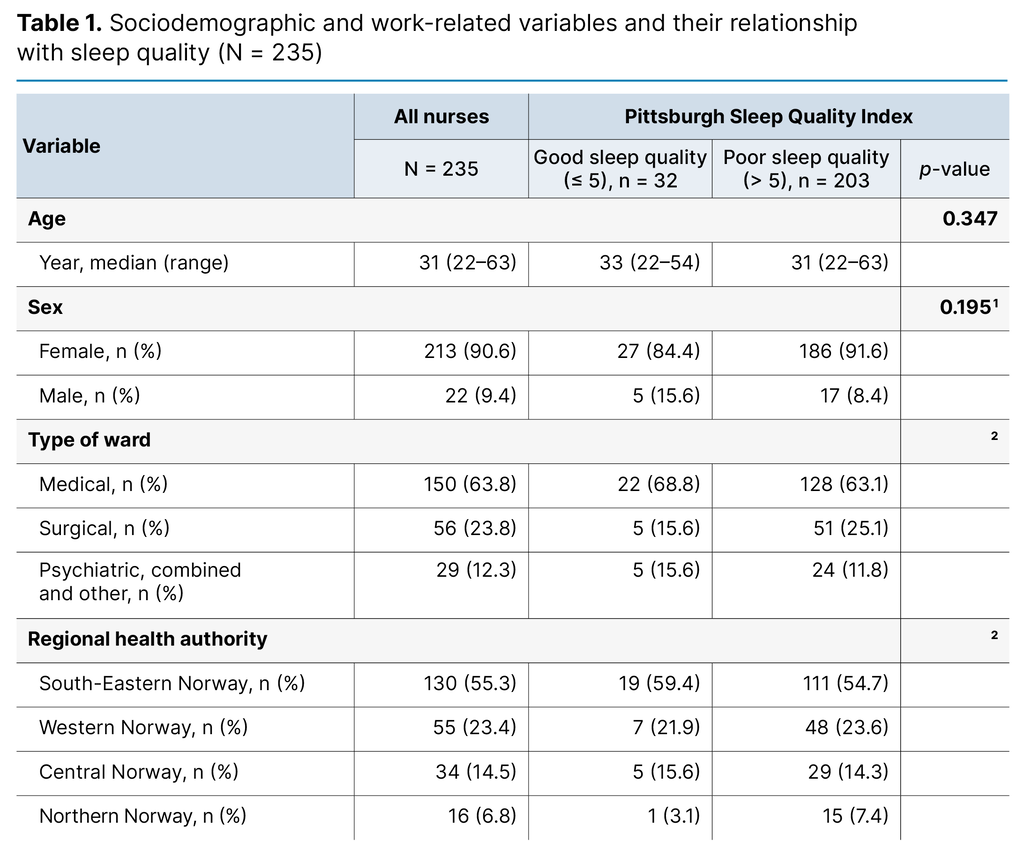

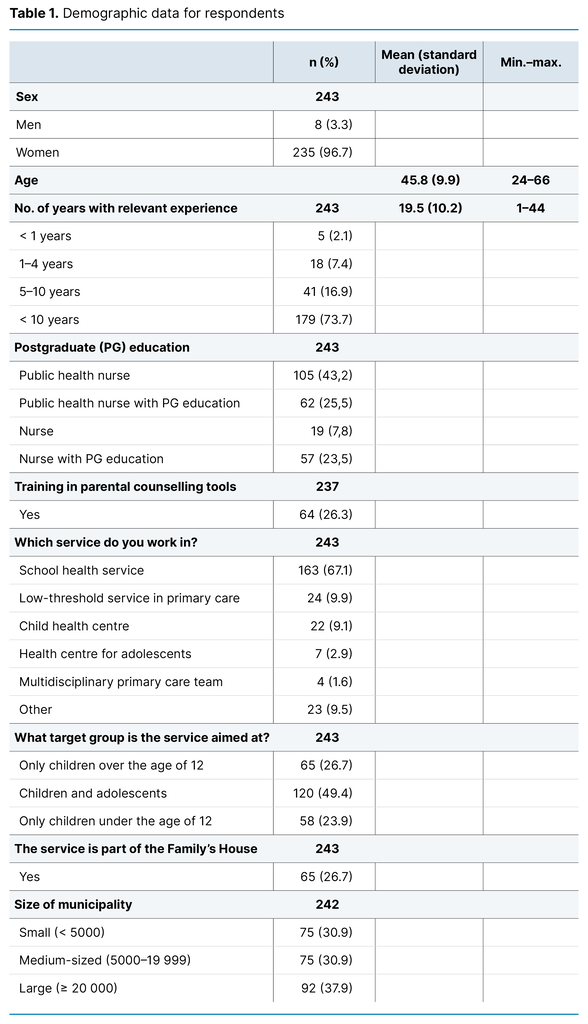

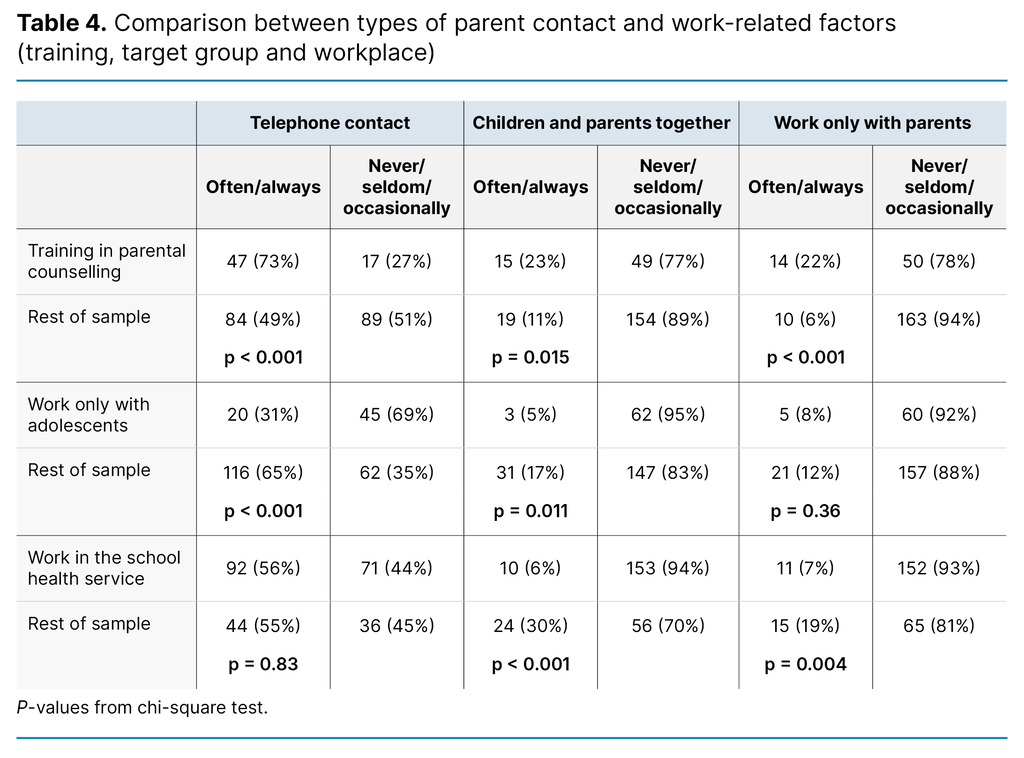

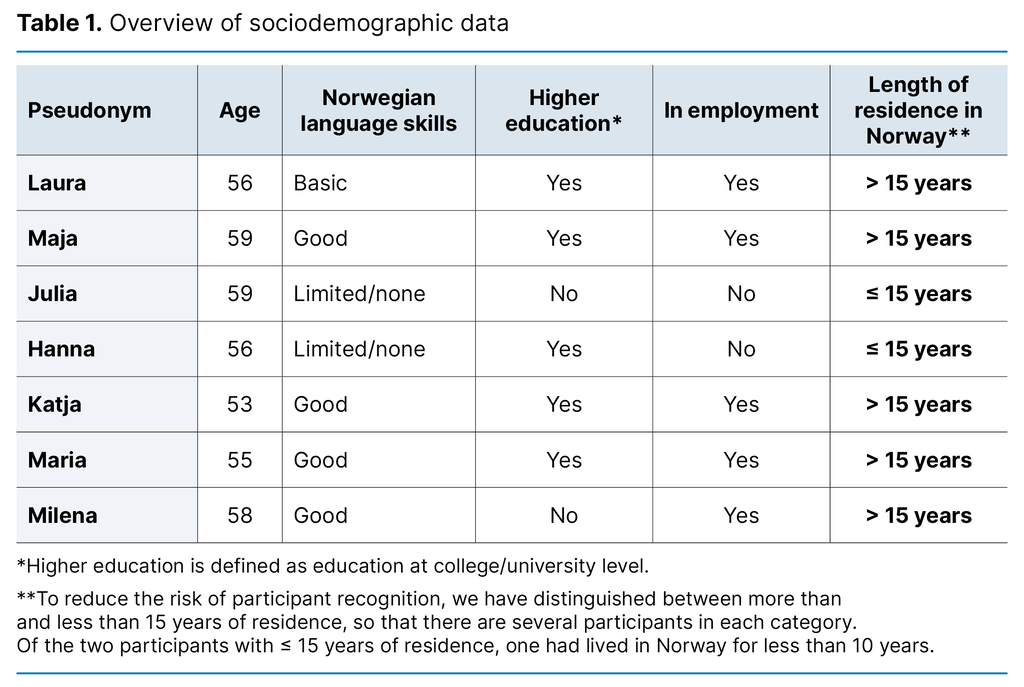

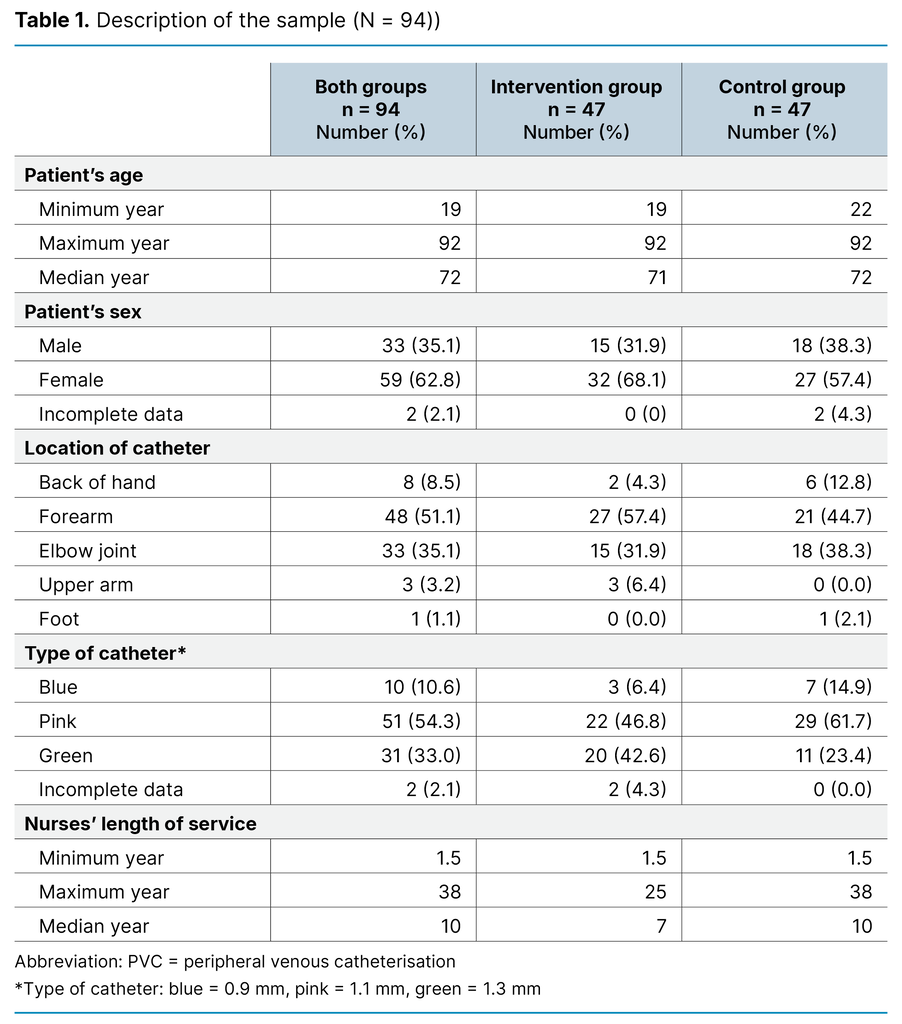

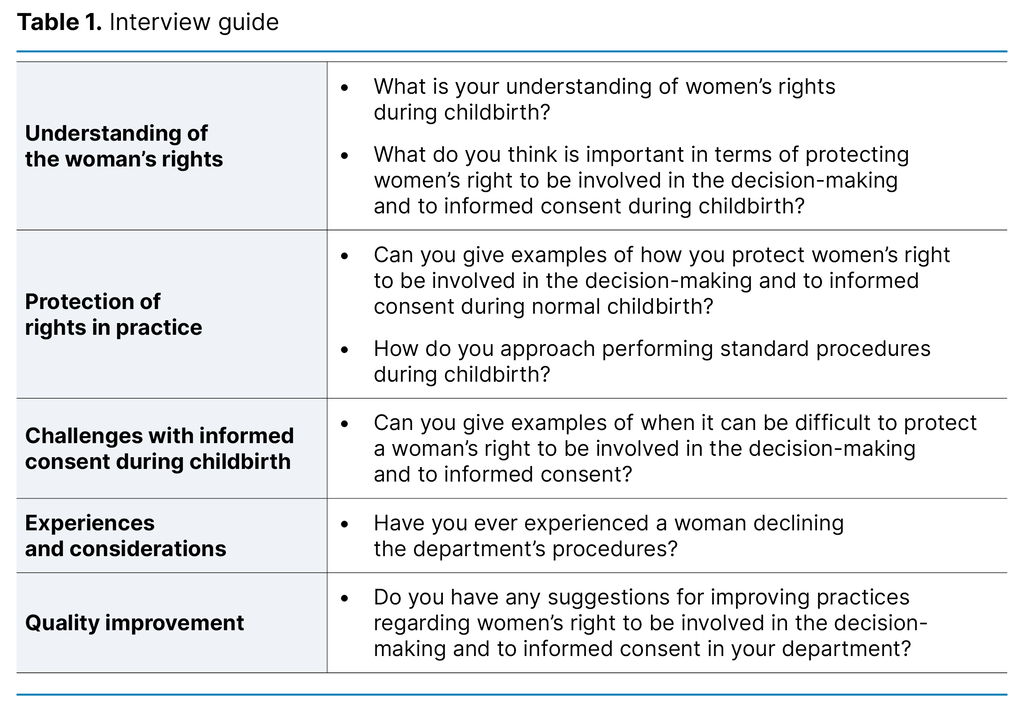

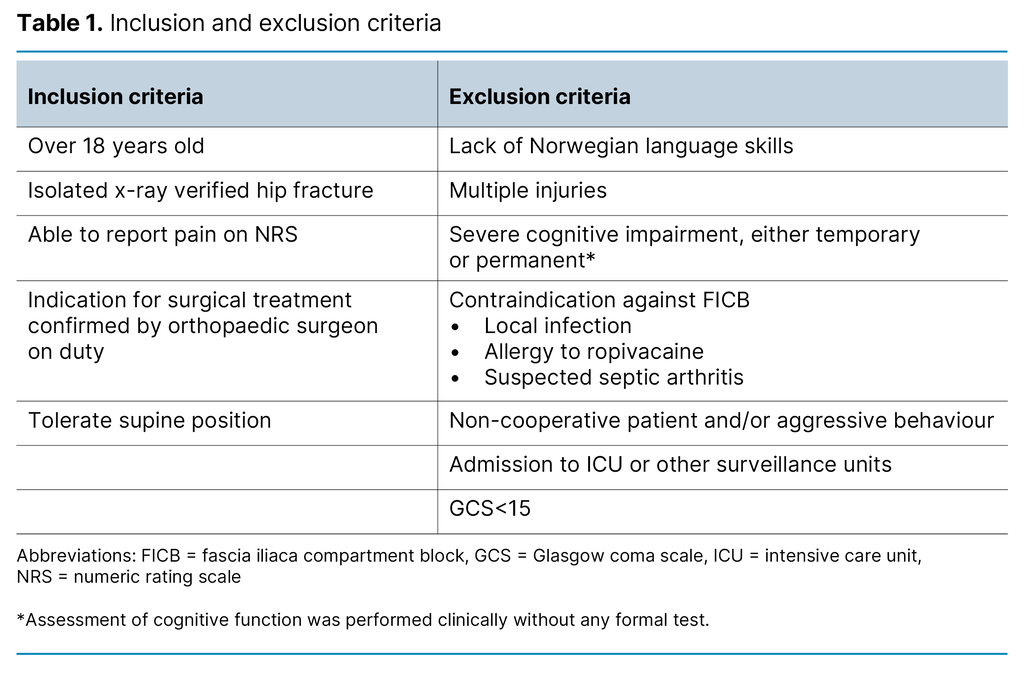

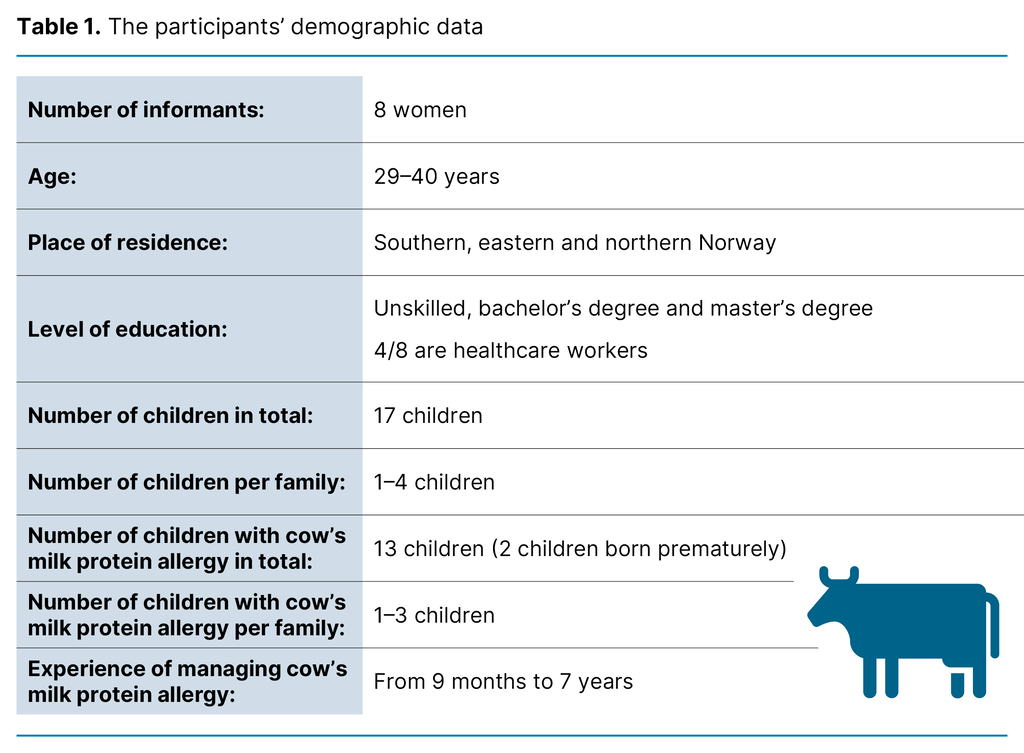

Table 1 shows the Norwegian Directorate of Health’s national reporting on the extent, location and patient populations for MIPAC services in 2019 (26). Patient data on sex, age and reason for admission have remained relatively stable since 2017 (27).

Appropriate use of scoring tools challenges and promotes clinical competence (12, 16, 18, 19). Units vary in respect of competence, the proportion of registered nurses and the proportion of nurses with specialised competence, as well as whether there is a contracted, designated doctor. These differences are partly related to structural frameworks and the diverse organisation of the services (21–24).

Competence is often low in MIPAC units located in long-stay units in nursing homes, particularly in Central and Northern Norway (24). Structural factors that promote competence include a high percentage of RNs on the staff, organisation in short-stay units, intermunicipal cooperation and the establishment of a professional development nurse position (3, 23).

This study explores the use of scoring tools for early identification of exacerbation of somatic disorders. The tools included EWS and the sepsis scoring tools in use at the time of the investigation: qSOFA and SIRS. We also examined the use of scoring tools to assess fall risk and nutritional risk.

The health authorities expect these decision-making support tools to be applied in RNs’ decision-making processes at all levels of primary care. As there was little knowledge of the extent to which these tools were systematically used in MIPAC services, we formulated the following research questions:

- To what extent are scoring tools used in MIPAC services in Norway?

- Are there differences in the use of scoring tools countrywide and in the organisational context?

- Can structural factors explain why the use of scoring tools to support decision-making varies in MIPAC services?

Method

Design

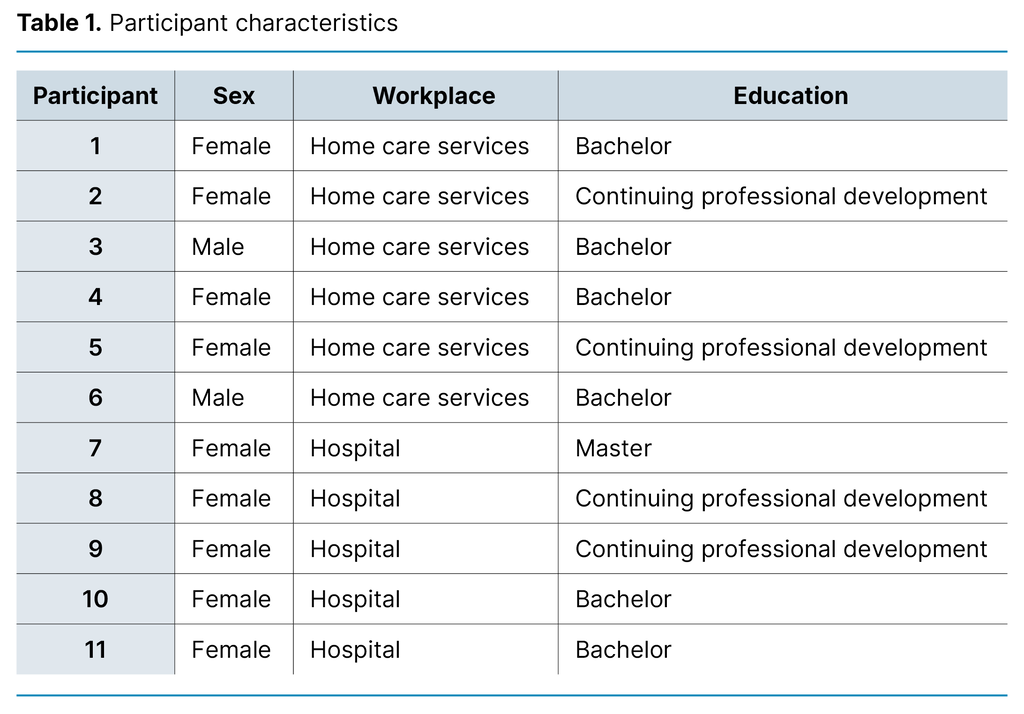

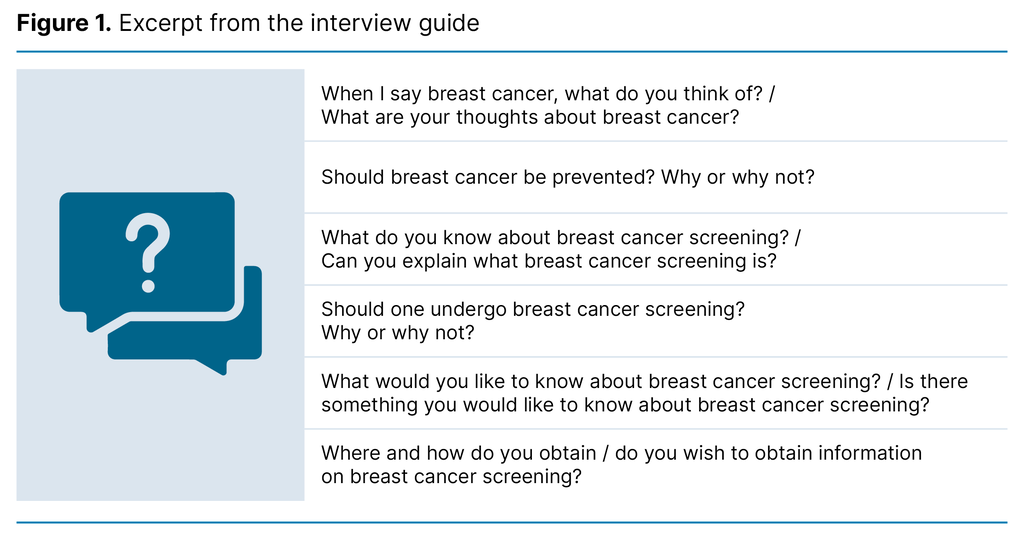

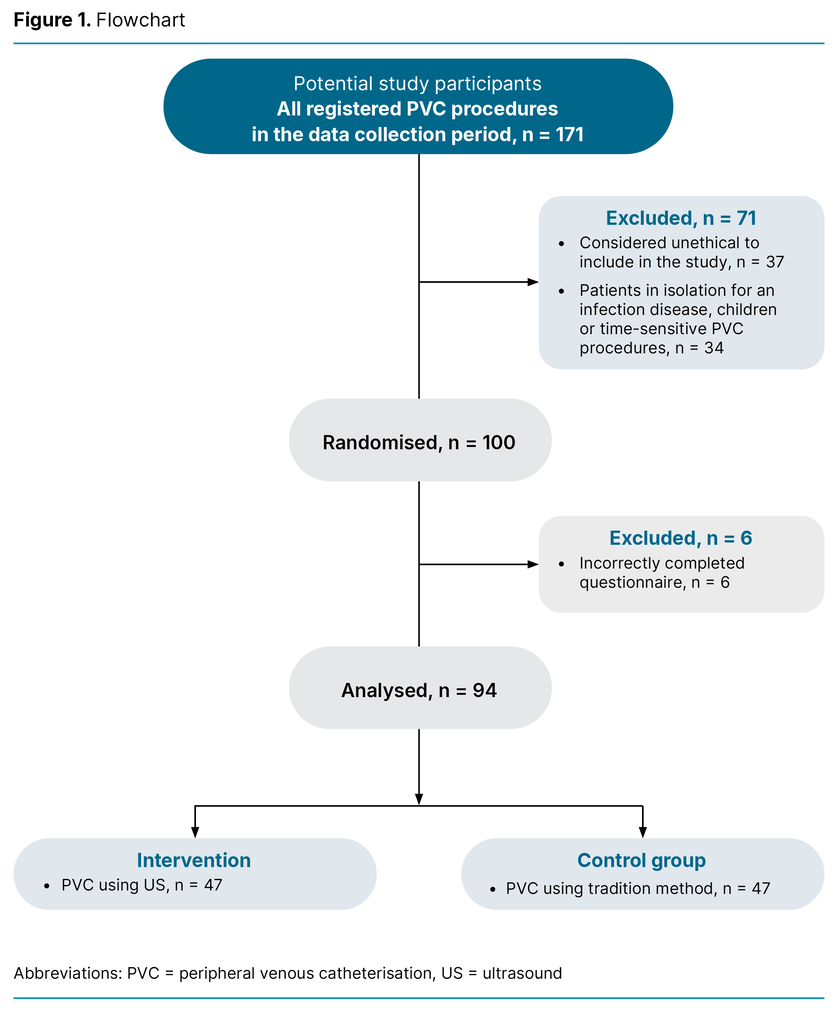

To acquire knowledge about the systematic use of scoring tools in Norway’s municipalities, we conducted a cross-sectional study among first-line managers at MIPAC units. An online questionnaire was used in the data collection. We chose first-line managers as respondents because we believed that they were best qualified to answer the questionnaire.

Sample and recruitment

For information about the location of MIPAC services in Norway, we used an email list from the Norwegian Directorate of Health supplemented with information from the host municipalities. We obtained contact information for the first-line managers from the respective municipalities. We assumed that first-line managers had best knowledge of the units and were therefore best qualified to answer questions on their use of scoring tools.

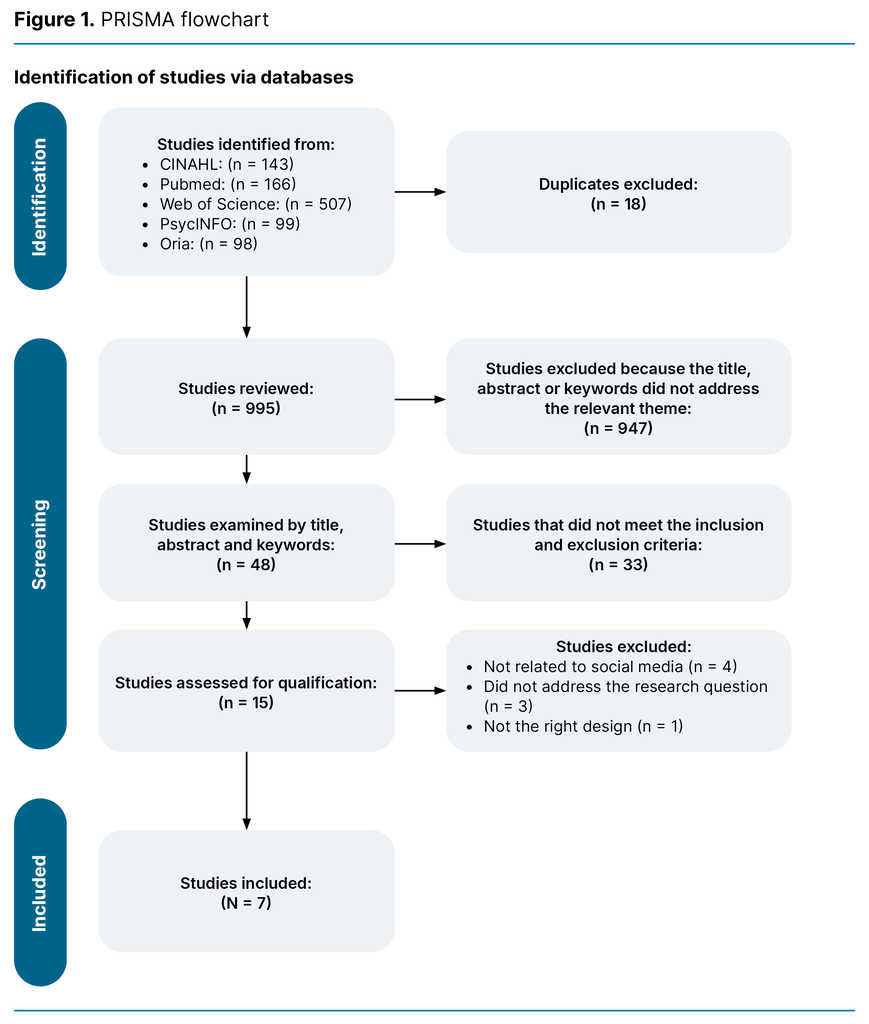

A total of 226 units (100 per cent) with MIPAC beds were identified. First-line managers were contacted by telephone and asked to participate after having received oral information about the study. We obtained email addresses from those who wished to participate and sent them an information letter and a link to the digital questionnaire.

Data collection

The questionnaire used in this study (Attachment 1) was developed by the first, second and third authors based on our previous research (3). It was also used in a study to identify nursing competence in MIPAC services (24).

We use the online platform SurveyXact to gather data over a three-month period. The questionnaire was distributed on 6 March 2019 and data collection ended on 6 June 2019. Two reminders were sent.

Variables

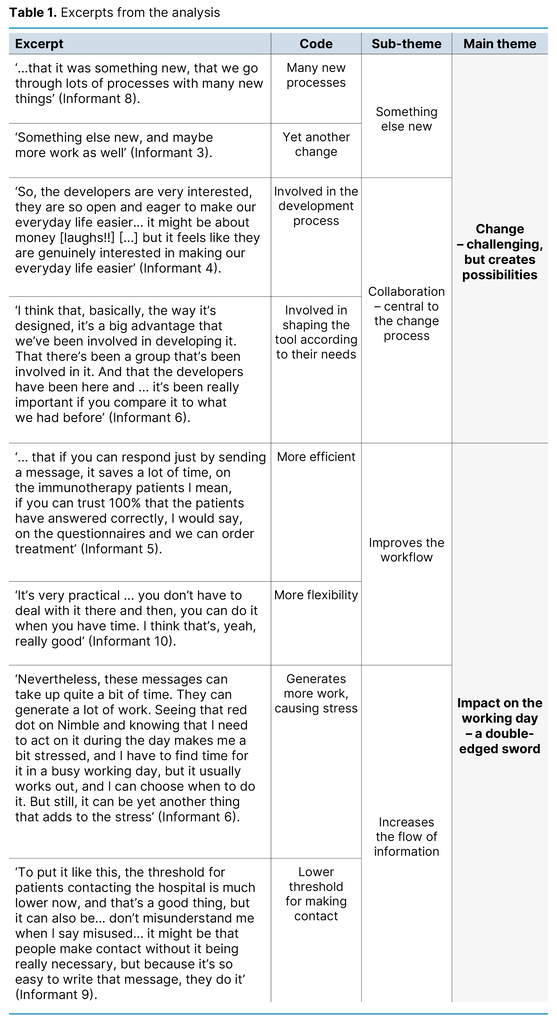

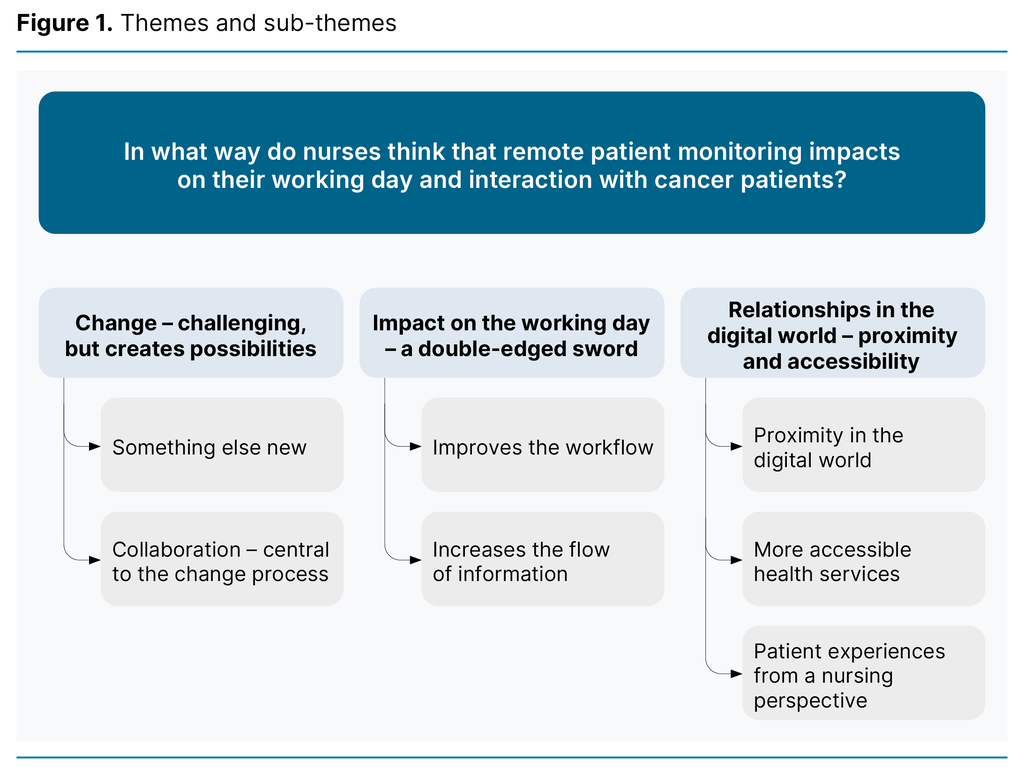

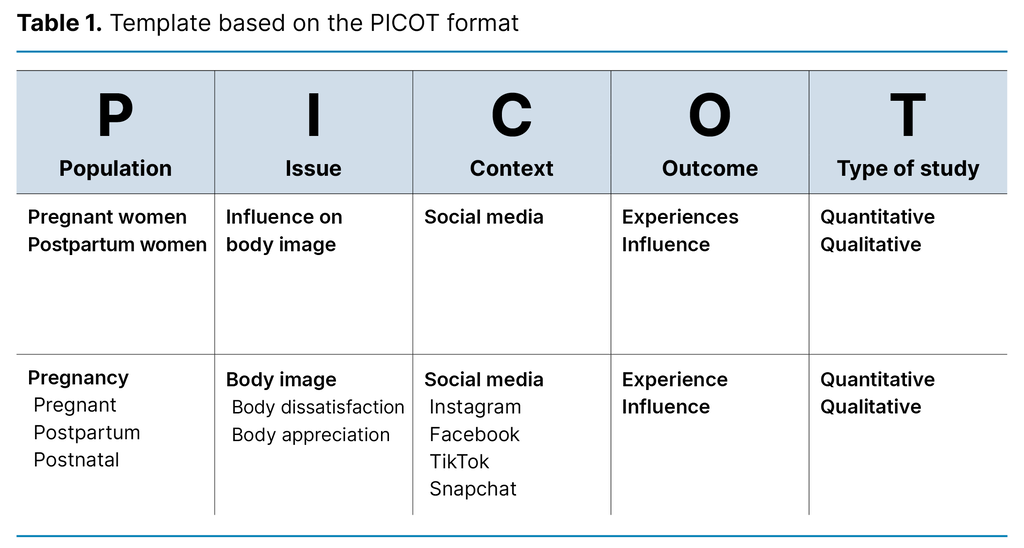

The respondents were asked to state how often the following scoring tools were used: a) EWS, MEWS, NEWS or TILT, b) sepsis scoring tools in use when we gathered the data: SIRS or qSOFA, c) fall risk scoring tools and d) nutritional risk scoring tools.

The response categories were ranked from 1–4 (1 = not used, 4 = always used). These variables were dichotomised (0 = not used, 1 = used). Geographical location (region) was dichotomised into a) South-Eastern Norway and Western Norway, and b) Central Norway and Northern Norway. This categorisation was based on earlier studies showing that the percentage of RNs on the staff and the percentage of units with standardised competence requirements vary from region to region (24).

The different types of MIPAC units were classified as: a) MIPAC unit only, b) MIPAC and short-stay unit, c) MIPAC and out-of-hours medical services, d) MIPAC and local medical centre, e) MIPAC, short-stay and long-stay unit, f) MIPAC and long-stay unit dichotomised into short-stay units (a, b, c, d) and long-stay units (e, f).

Respondents were further asked to state the number of RNs, and we calculated the proportion of RNs on the staff (percentage). The respondents were also requested to estimate the full-time equivalent for the professional development nurse position. This was dichotomised into ‘no’ (none) and ‘yes’ (> 1 per cent). Consequently, the unit had to have a professional development nurse working a minimum full-time equivalent of 0.01 for the response to be categorised as ‘yes’.

We conducted a pilot test of the questionnaire whereby five people from the target group provided feedback on logic, comprehensibility and structure in order to evaluate face validity. Their feedback resulted in some minor changes.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (28), and was evaluated by the former Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), now Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, on 28 January 2019 (reference number 815471) and the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Health and Sport Sciences, University of Agder (reference number MSG1715203).

The participants were contacted individually and received oral and written information about the study. The written information included a description of their legal rights in respect of participation. They were informed that participation was voluntary, and that responding to the questionnaire was regarded as consent. Anonymity was also guaranteed by the deidentification of individuals in reports and publications.

Analysis

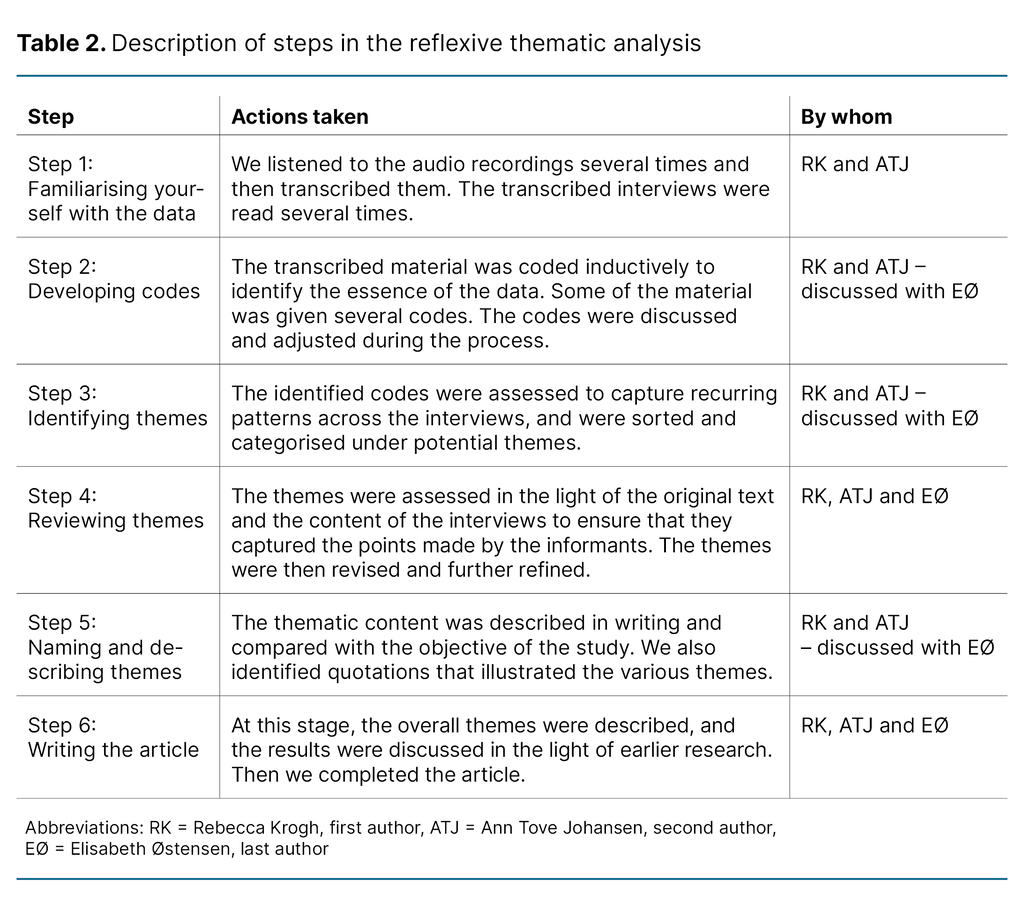

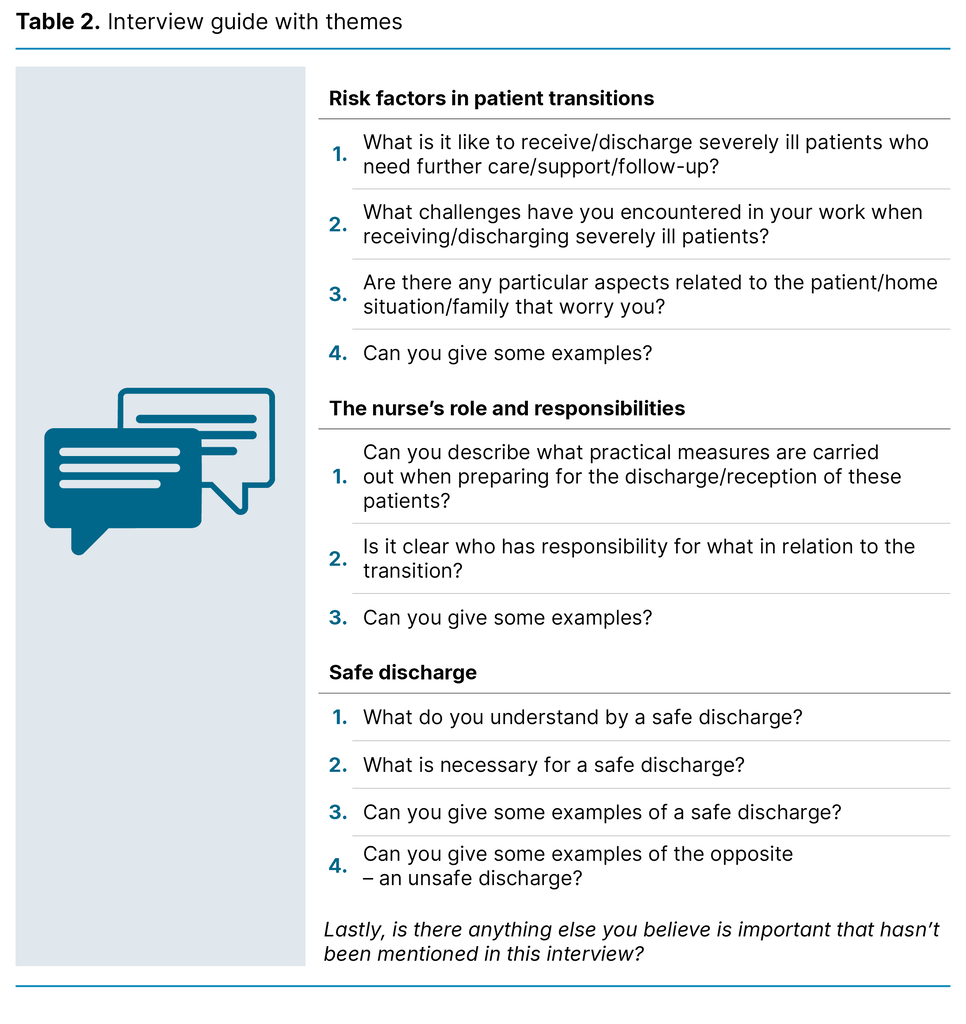

To describe the sample and the units’ reported use of the various scoring tools, we presented the data as number (n), percentage (%), median and interquartile range (IQR)). We also used the Mann-Whitney test and calculated the effect size (Cohens r) based on Z-statistics (r = z / √N) (29).

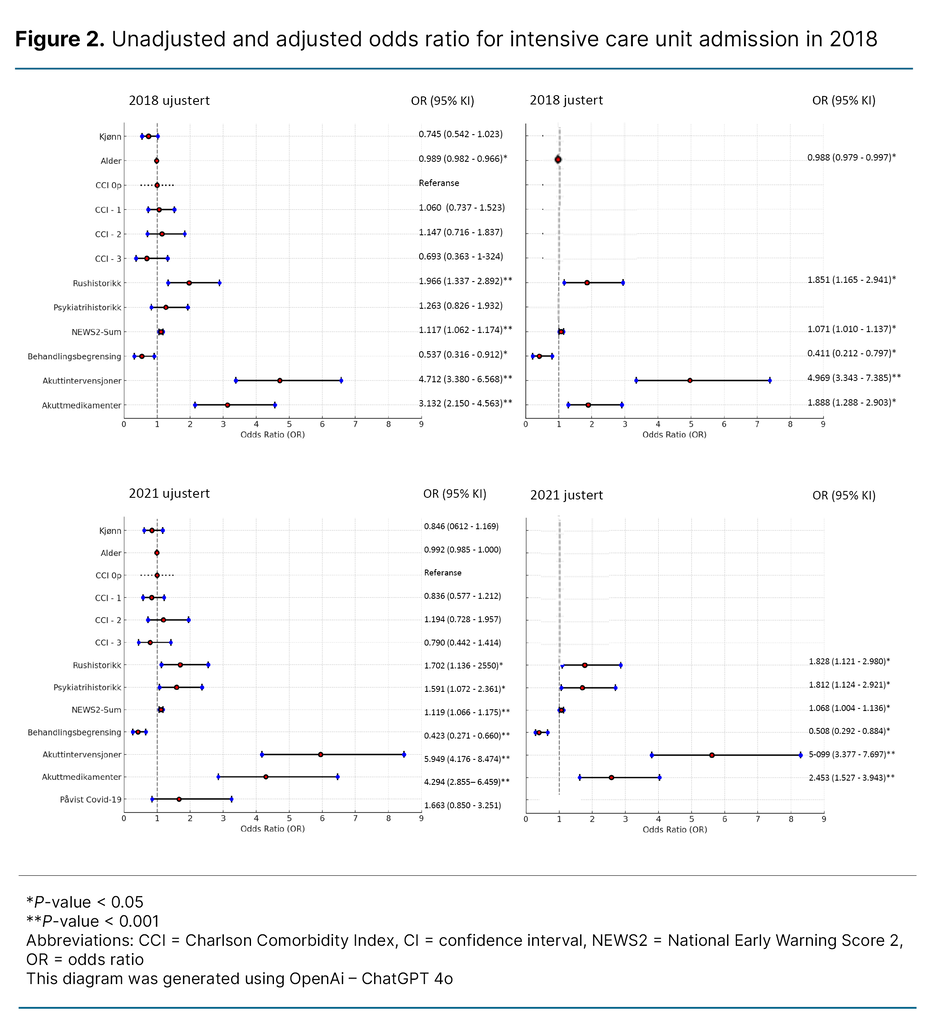

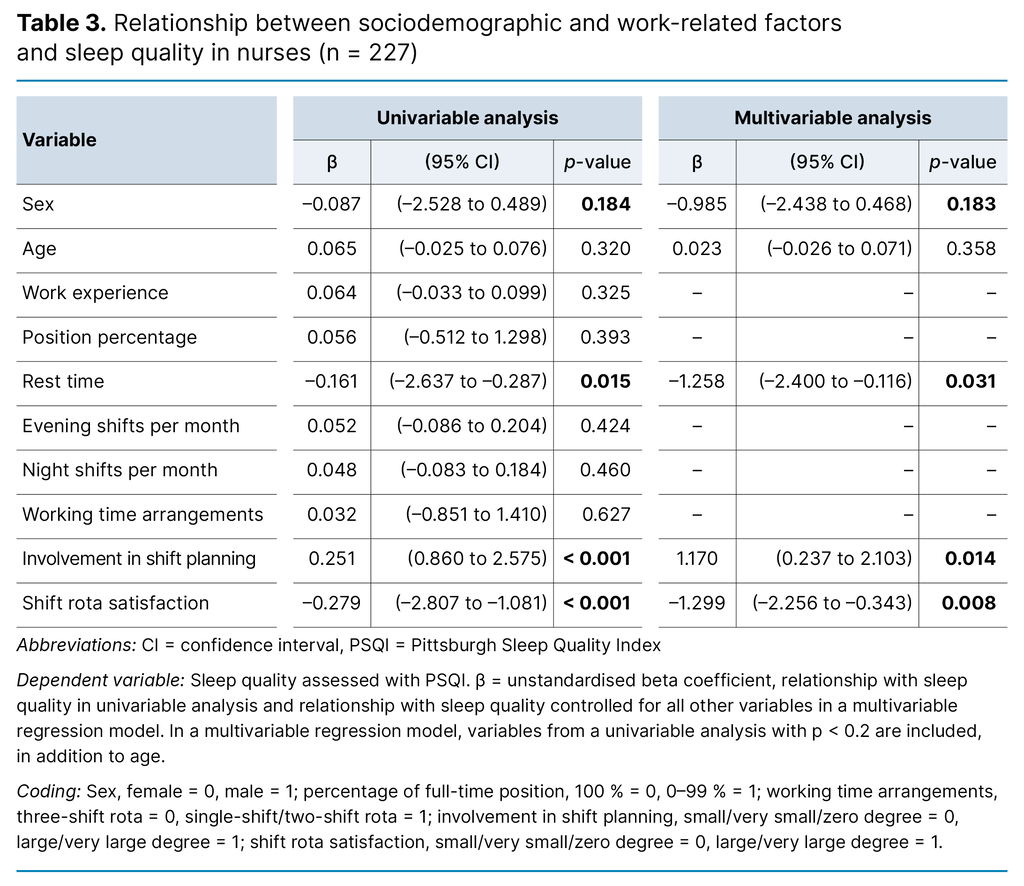

Finally we carried out four multiple logistic regression analyses. Dependent variables are the use of Early Warning Score, sepsis score, fall risk score and nutritional risk score (yes/no). Independent variables are region (South-Eastern/Western Norway and Central/Northern Norway), type of unit (short-stay and long-stay unit), organisation (intermunicipal/municipal), professional development nurse position (yes/no) and the proportion of RNs on the staff (percentage).

The results of the regression analyses are presented as unstandardised regression coefficient (B), 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) for regression coefficient (B) and odds ratio (OR) for B. The strength of the regression model is estimated by calculating the regression coefficients (Cox and Snell r2 and Nagelkerke r2, giving the lower and upper limits for explained variance.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all tests were two-tailed. Missing data were excluded from the analysis. We conducted the analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.

Results

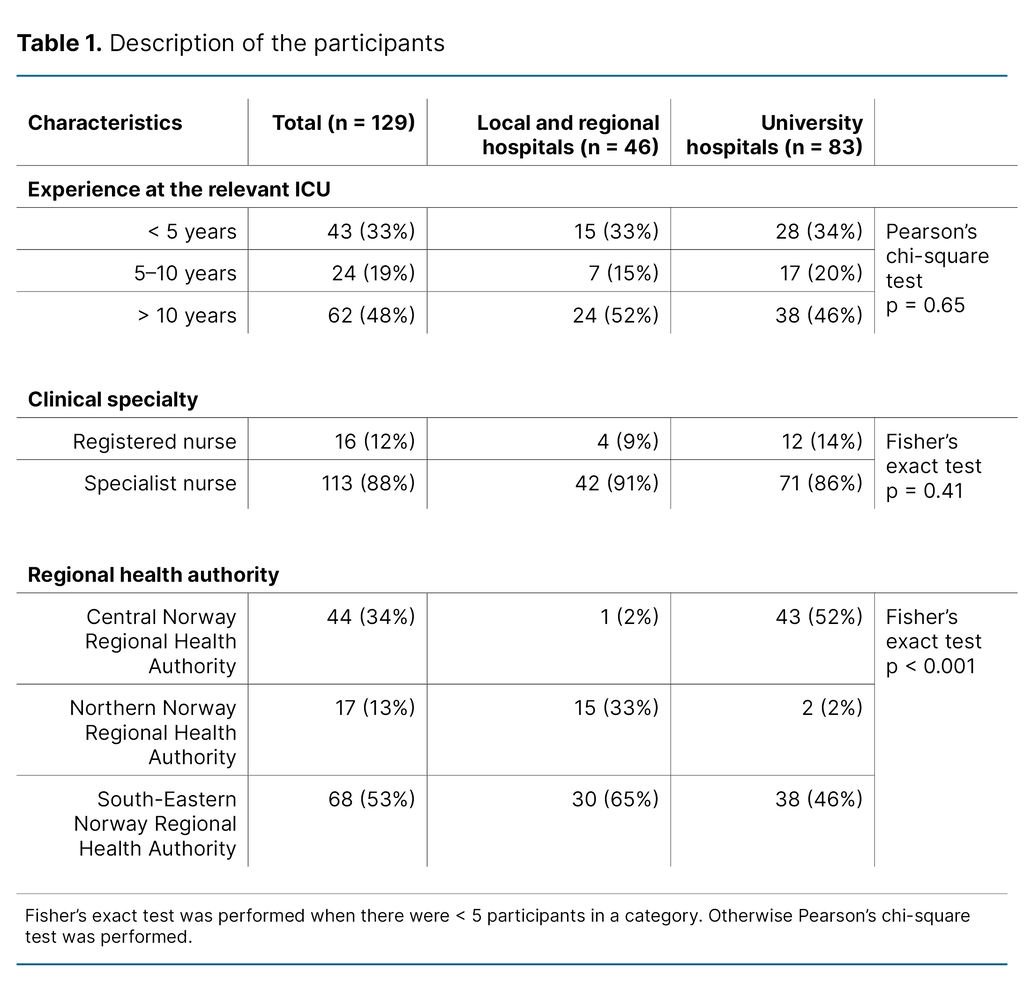

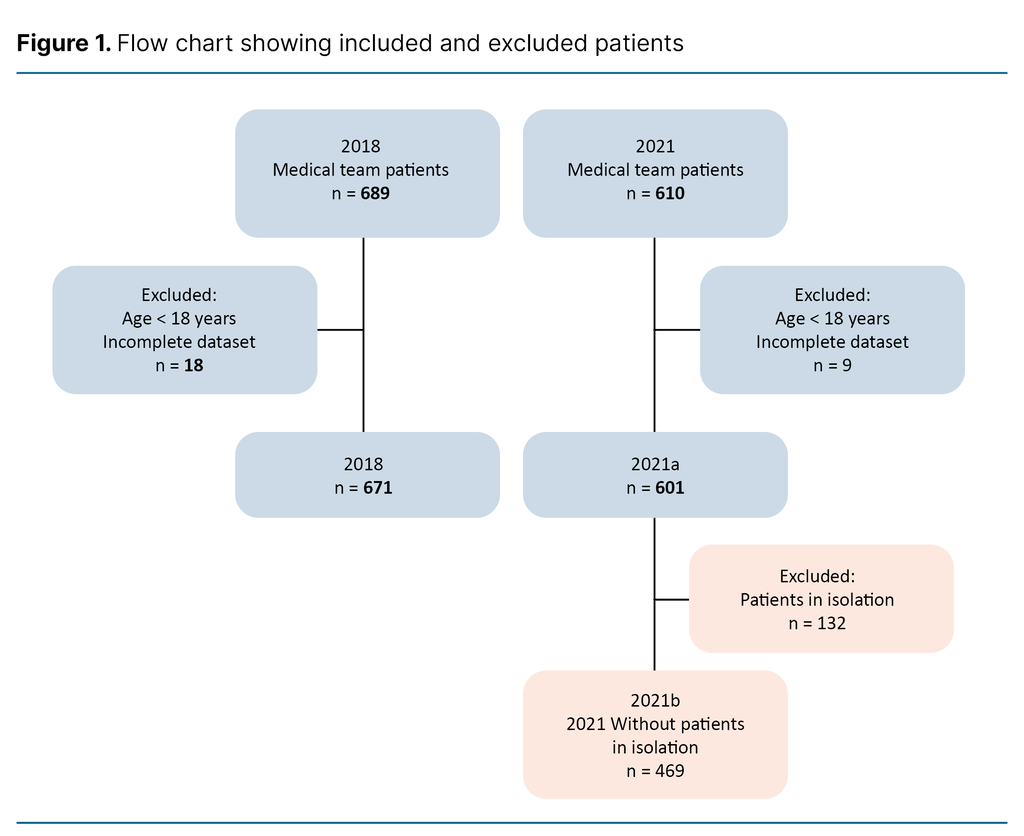

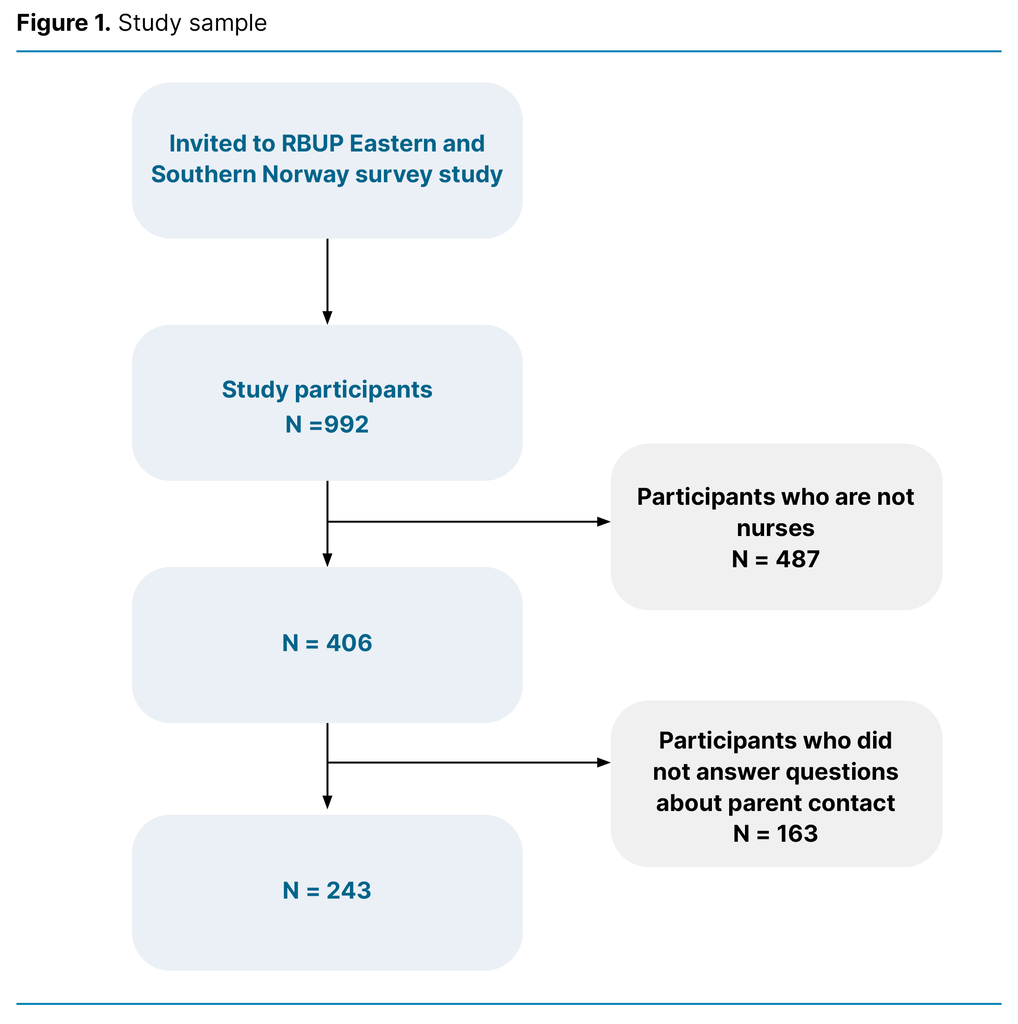

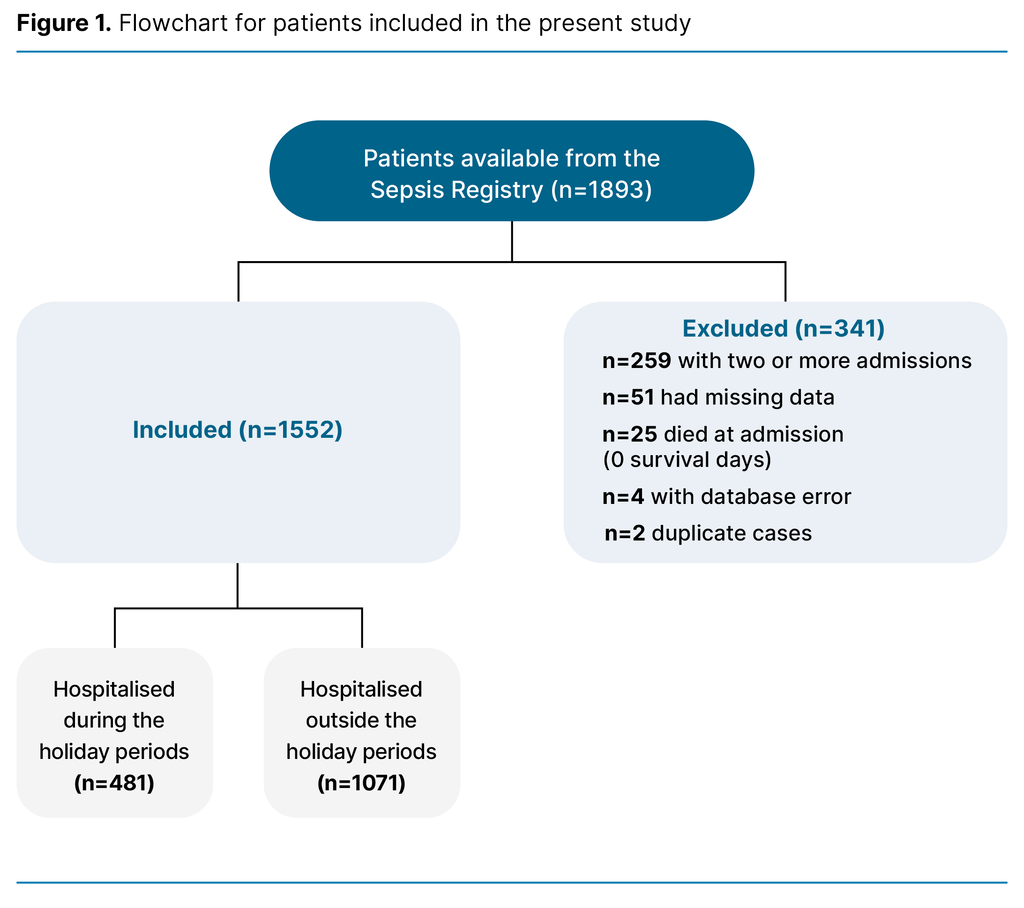

The study included 207 MIPAC units, representing 91.6 per cent of the population. A total of 108 units were located in South-Eastern and Western Norway, 42 of which (39 per cent) were intermunicipal MIPAC units. Of the 99 units located in Central and Northern Norway, 22 (25 per cent) were intermunicipal MIPAC units. Some 101 MIPAC units had managers with responsibility for long-stay units and MIPAC beds.

A total of 64 (63 per cent) were located in Central and Northern Norway. The median percentage of RNs on the unit was 56 (IQR: 38‒ 78), and 109 (55 per cent) of the units had an associated position for a professional development nurse. Some 59 per cent of the MIPAC units located in South-Eastern and Western Norway had a professional development nurse position while in Central and Northern, the percentage was 46 per cent. The number of MIPAC beds in the units varied from 0.2 to 34.

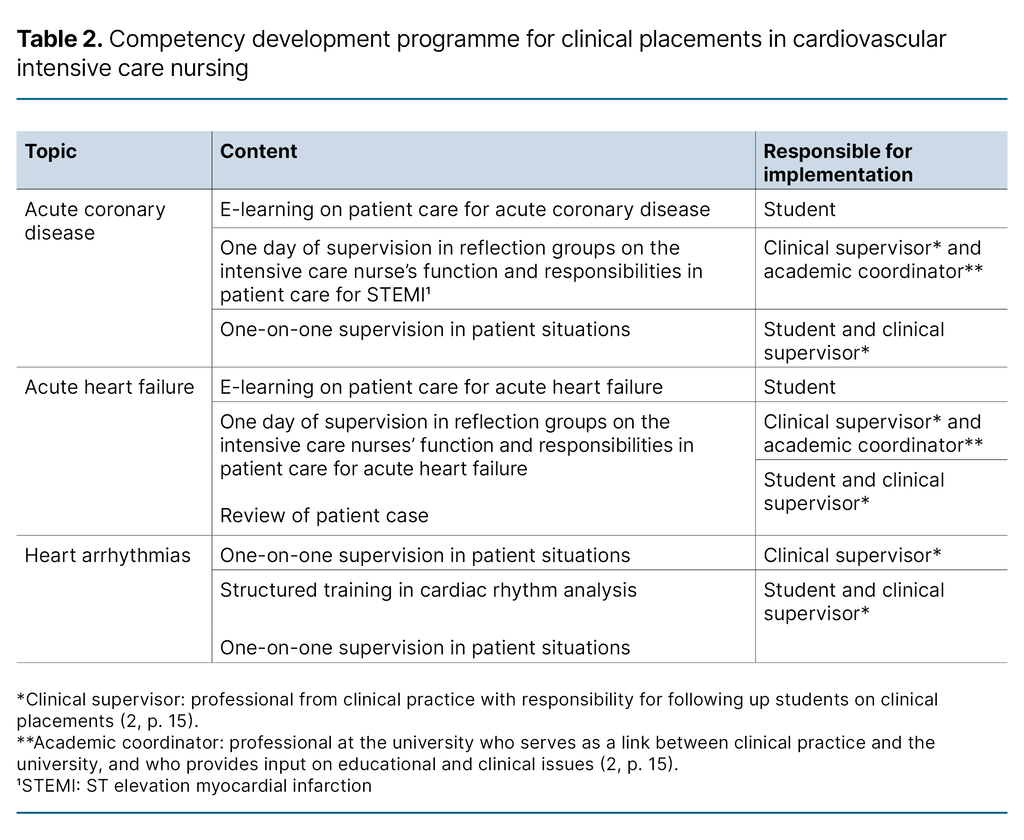

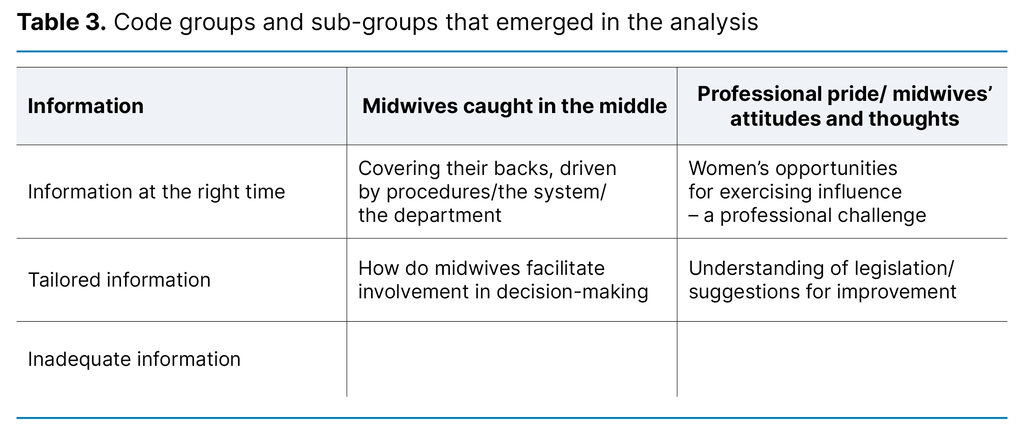

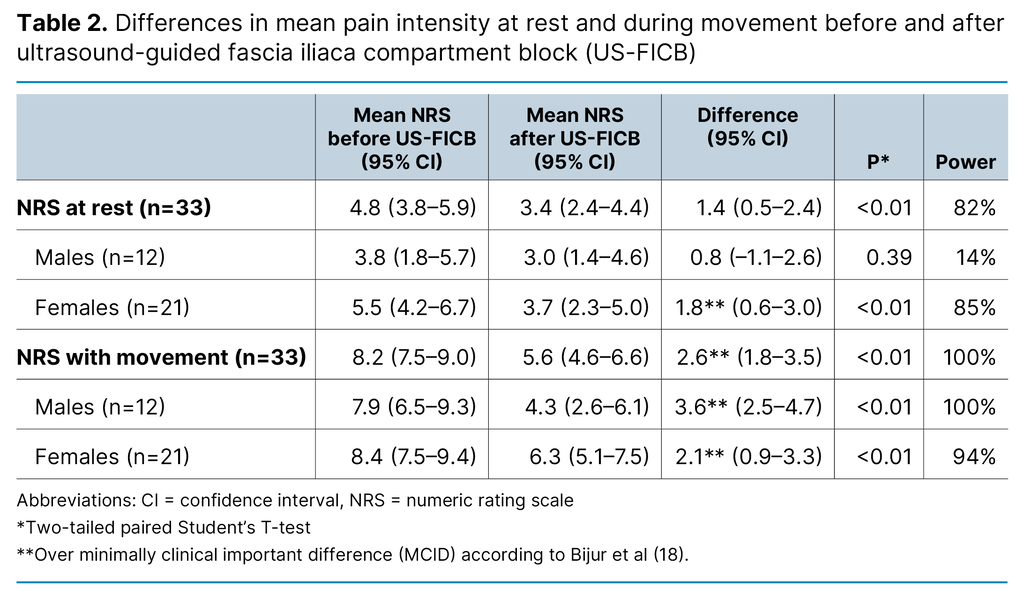

Systematic use of scoring tools in MIPAC services

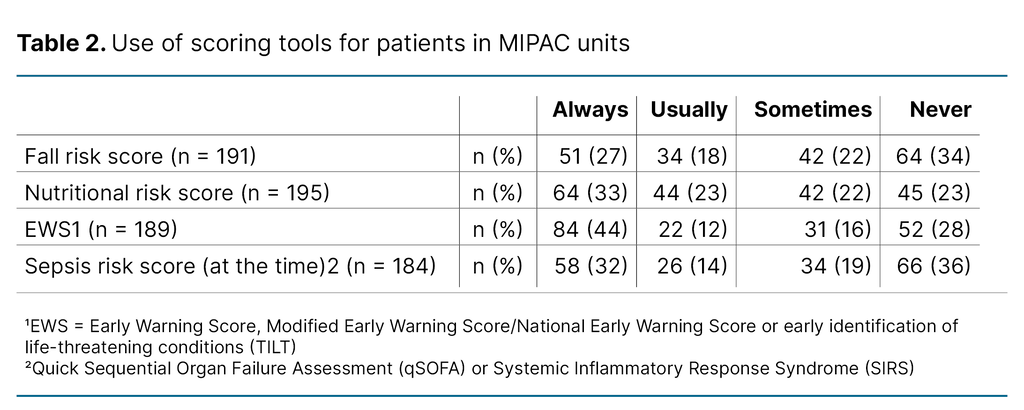

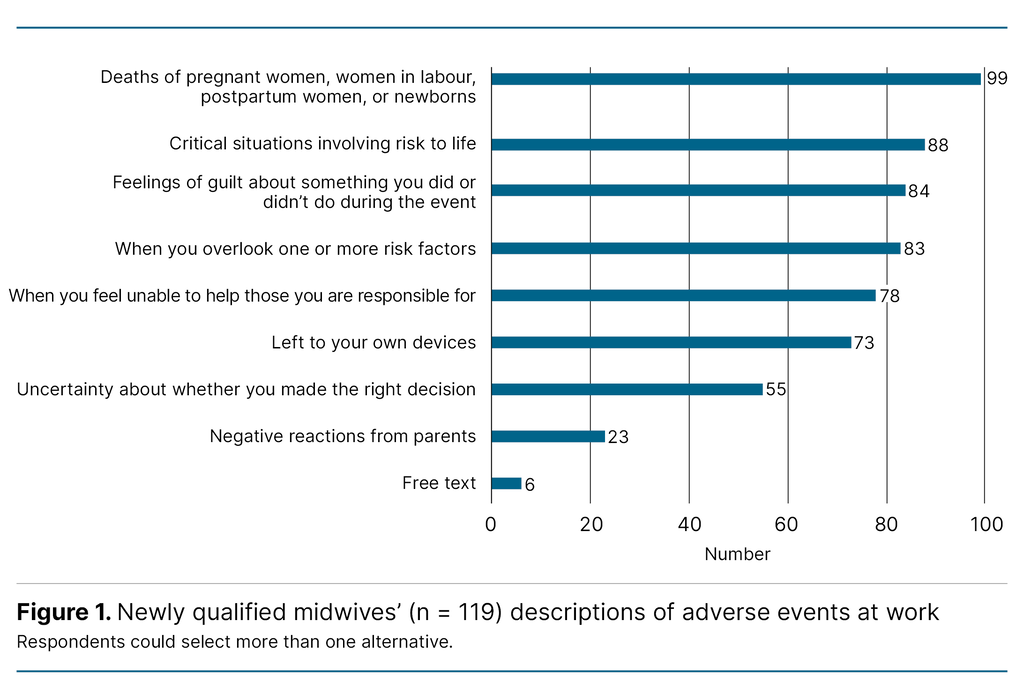

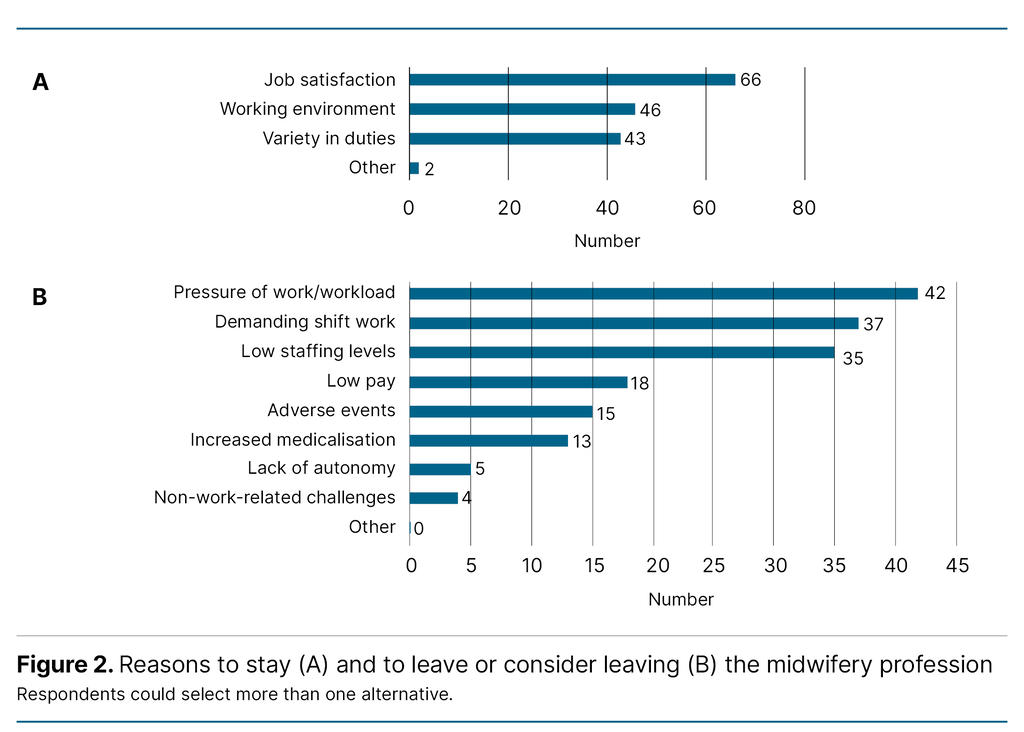

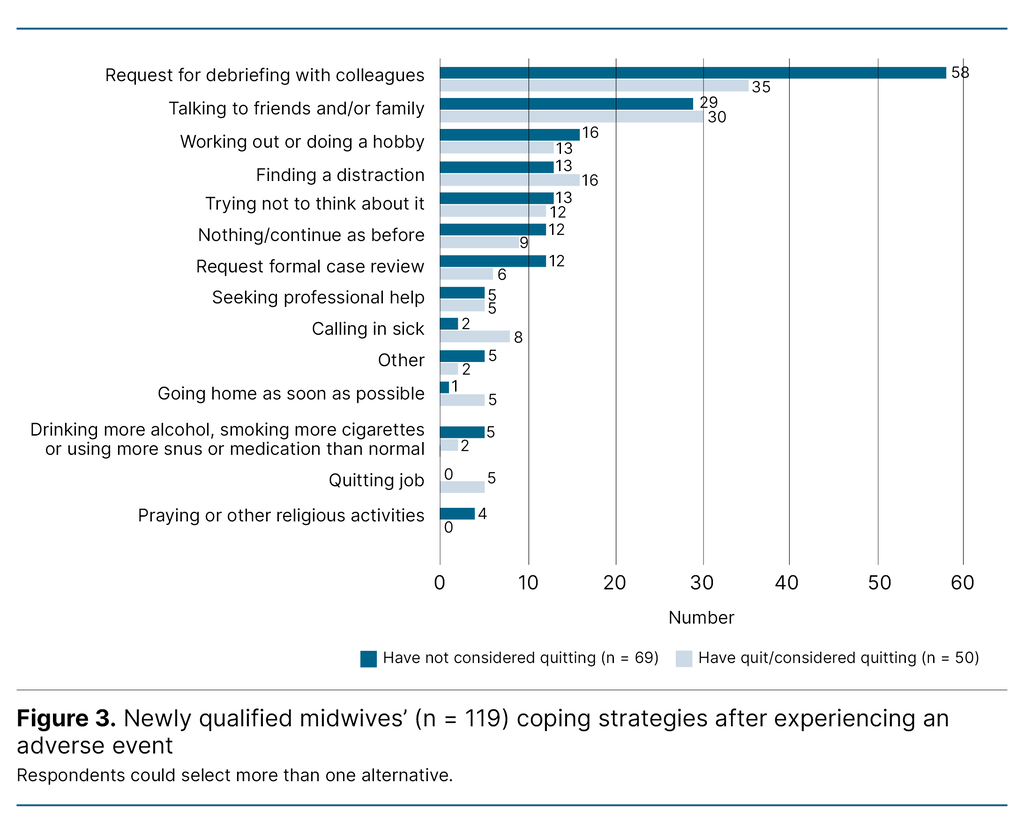

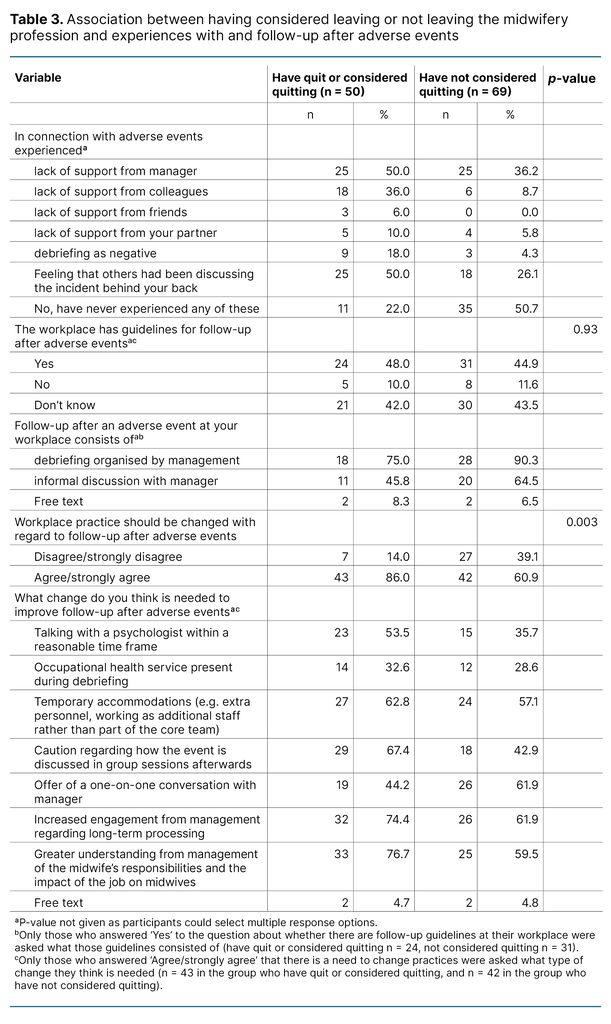

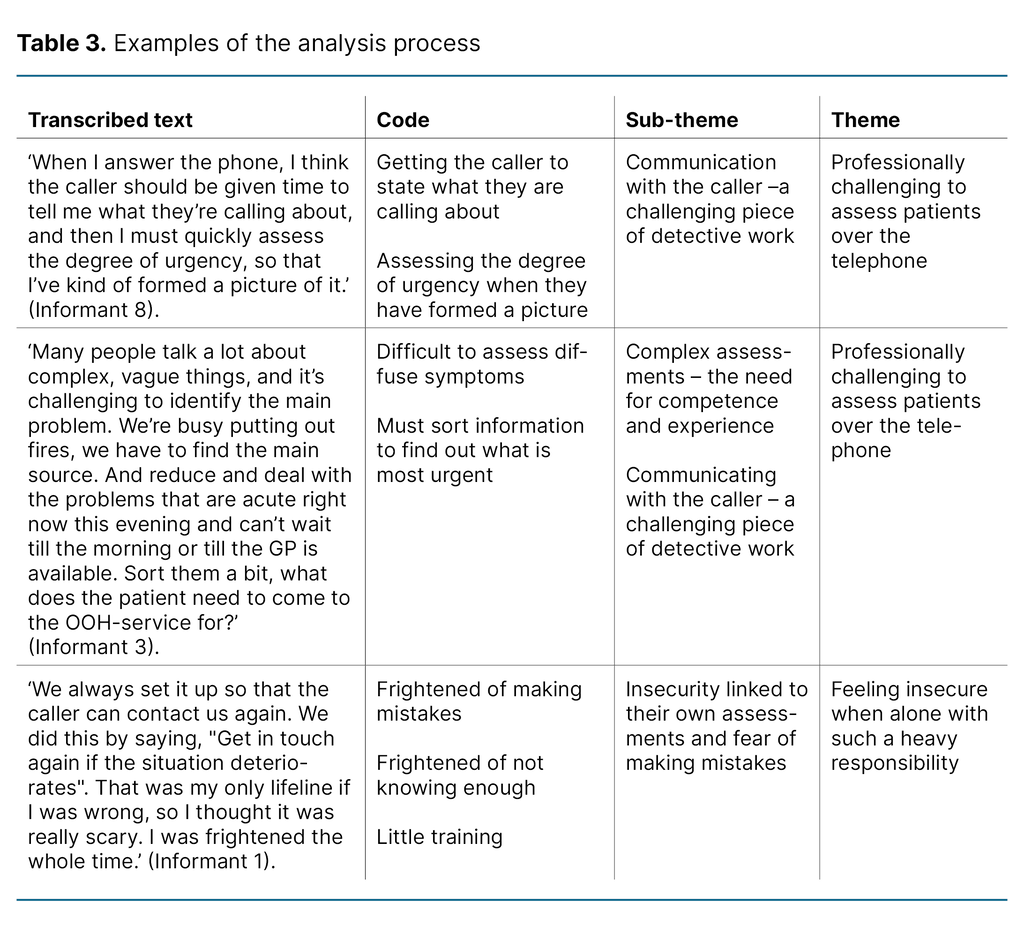

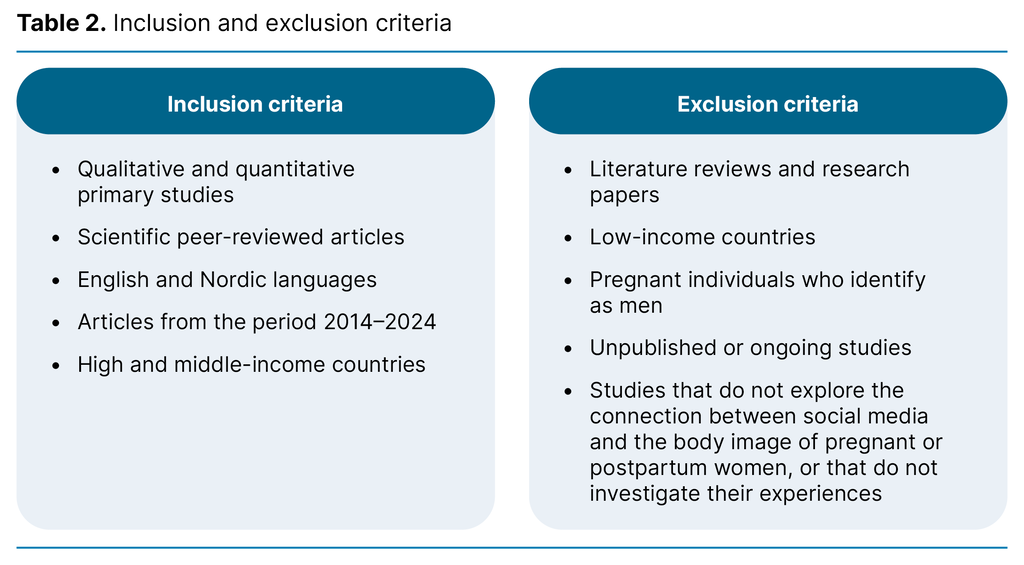

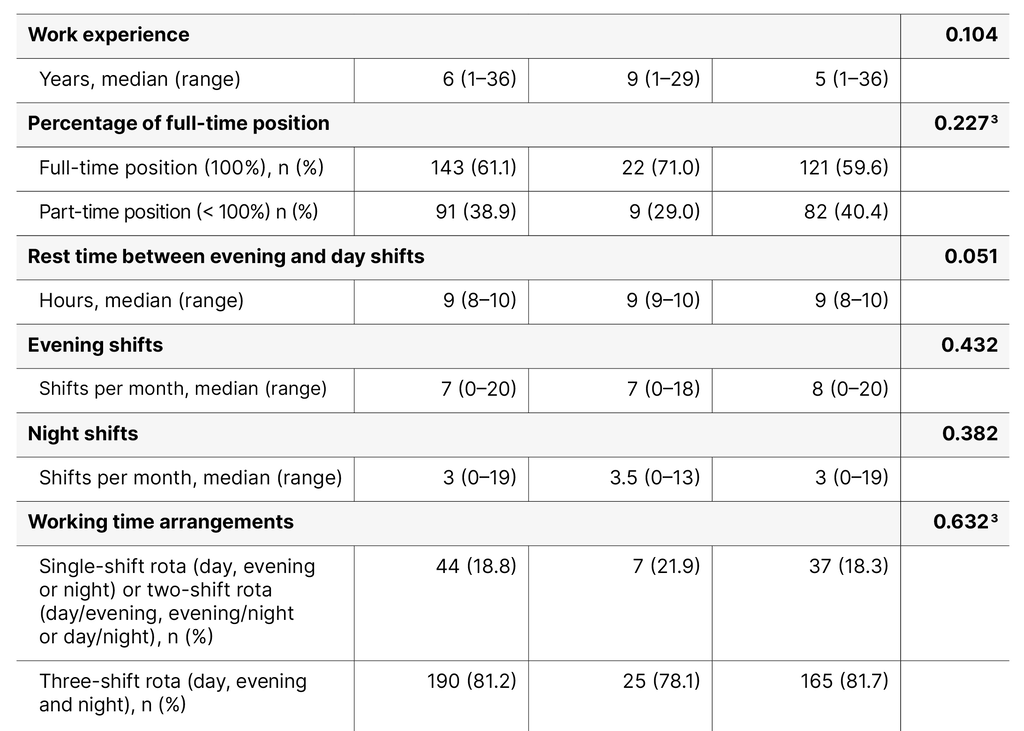

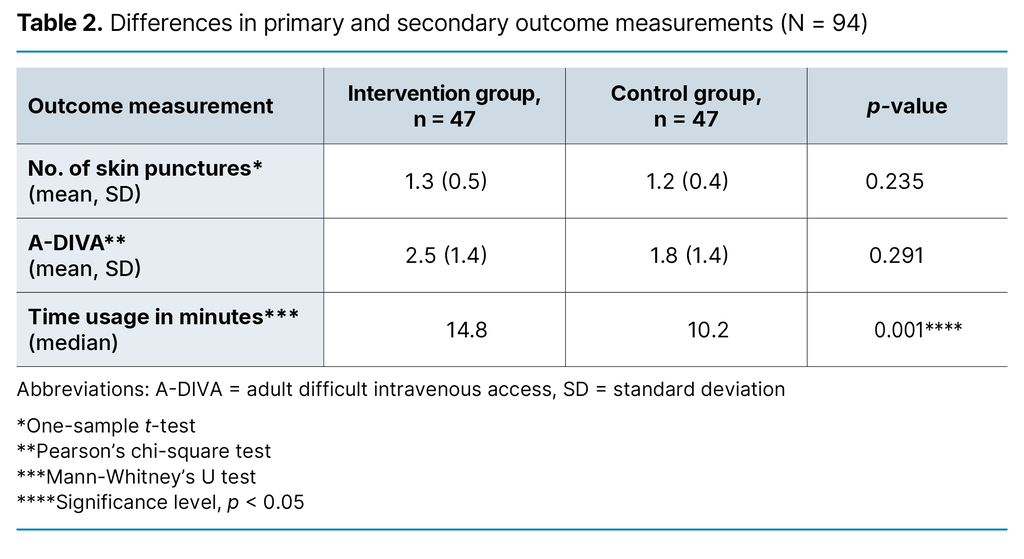

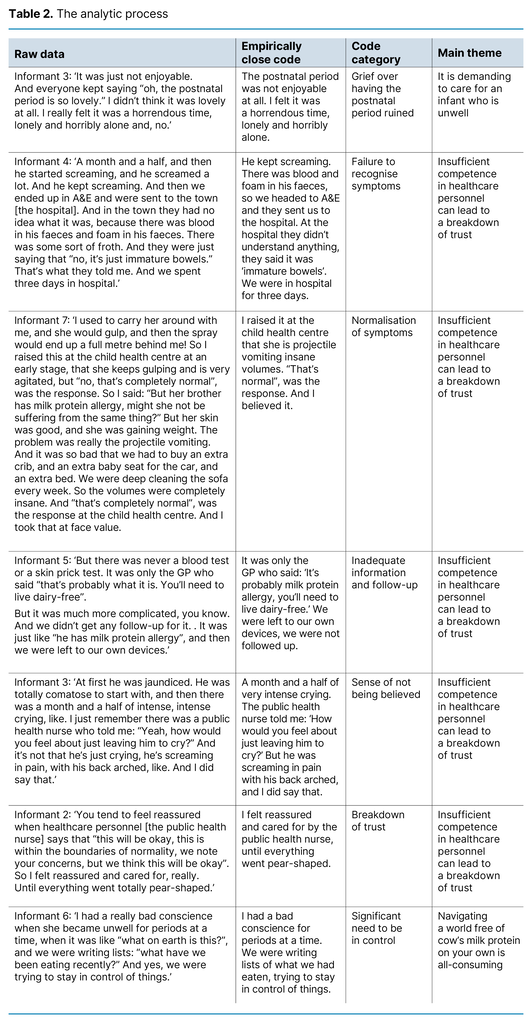

Some 56 per cent of the MIPAC units in the sample often or always used EWS, while 28 per cent did not use the tool. Furthermore, the results showed that 46 per cent of the units used the current sepsis score often or always for patients when infection was suspected, while 36 per cent did not use sepsis scoring tools.

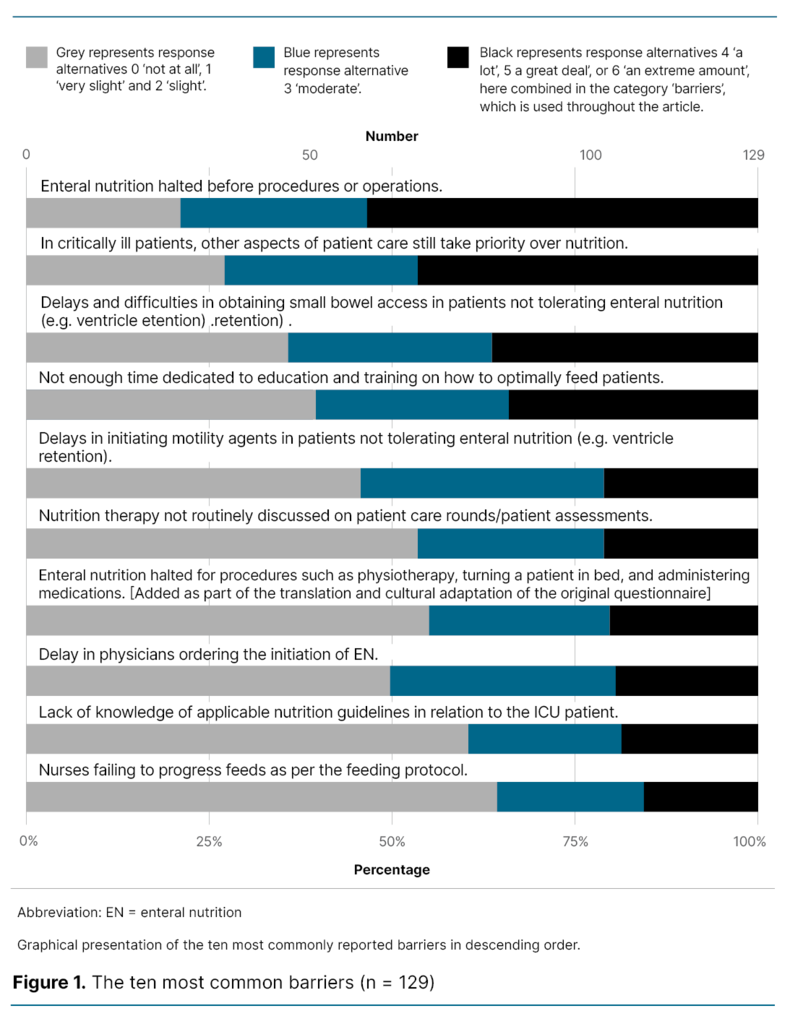

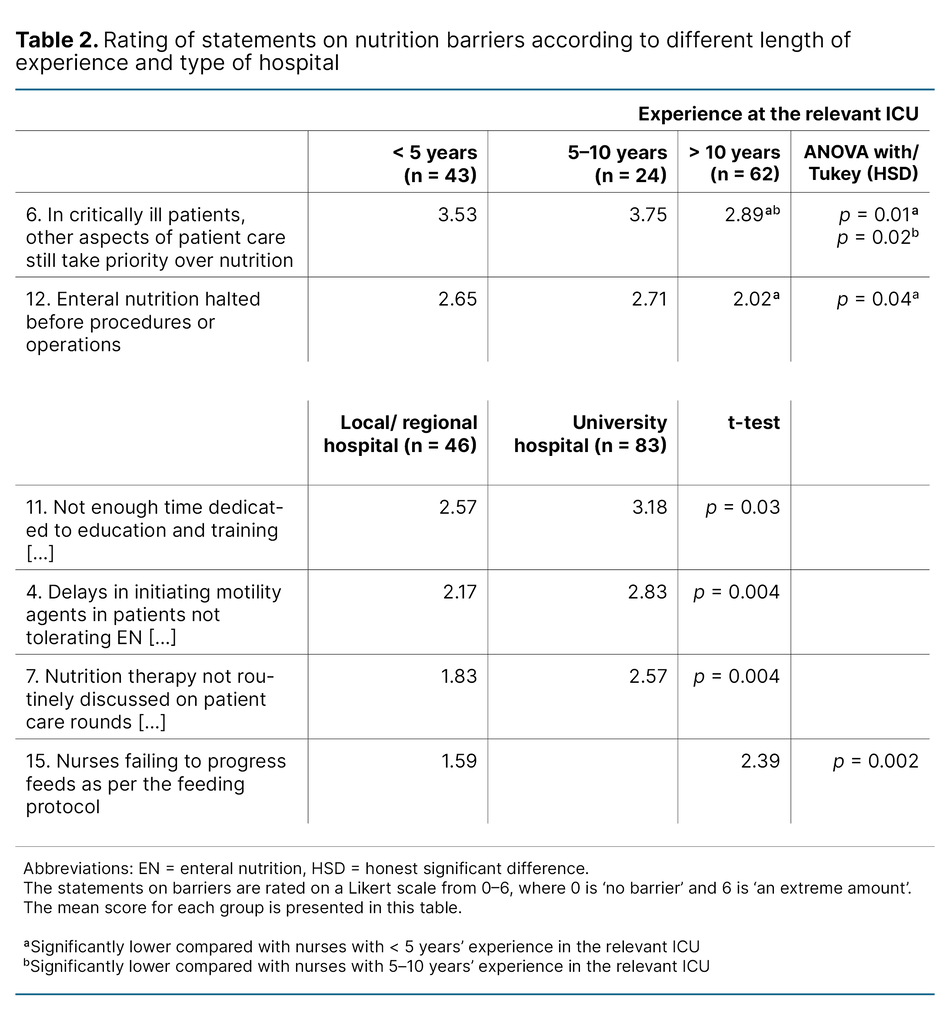

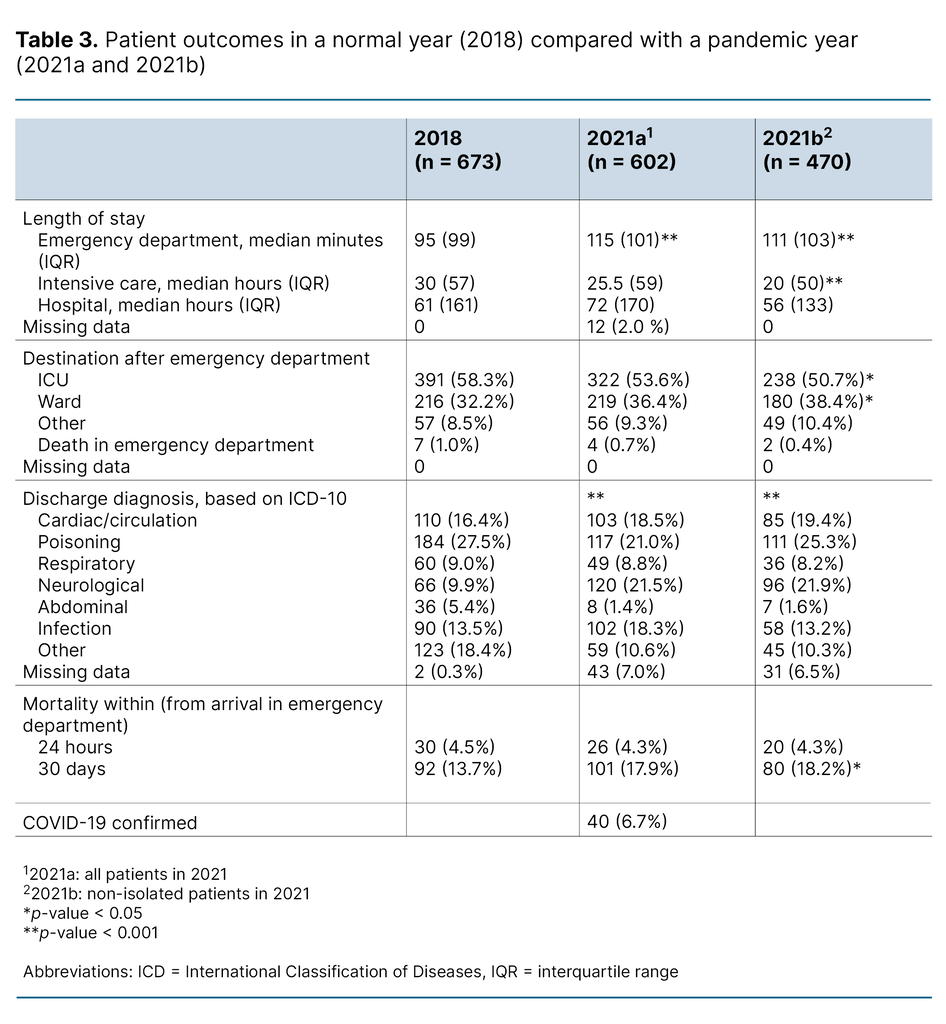

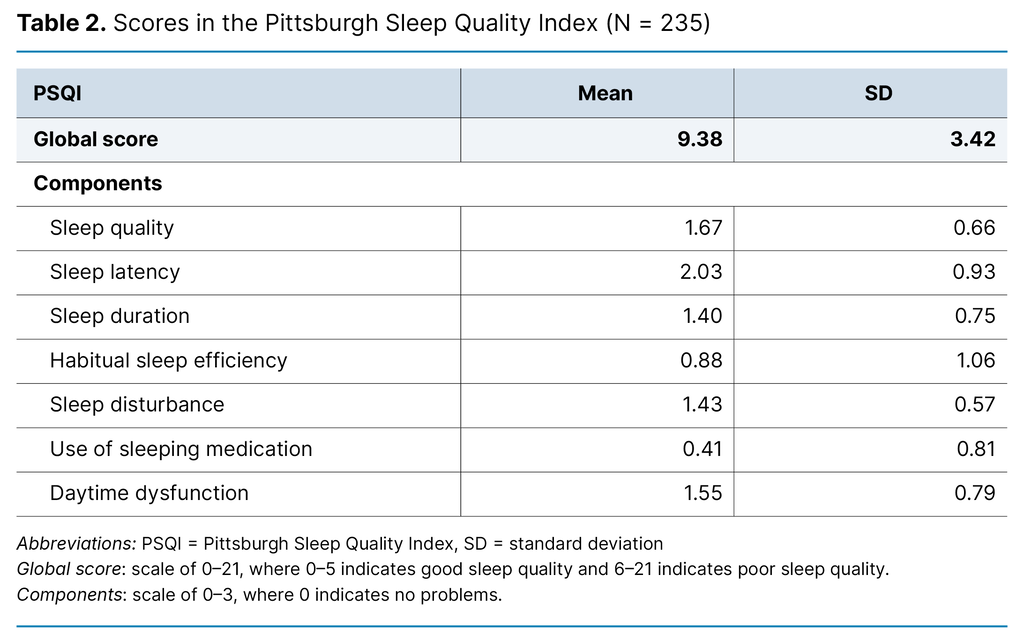

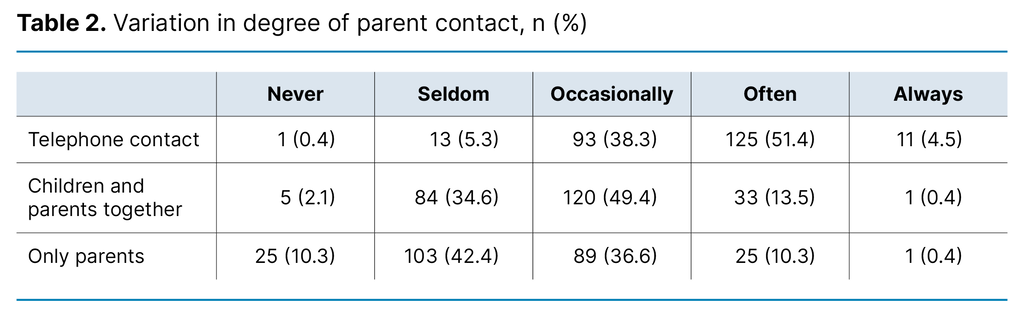

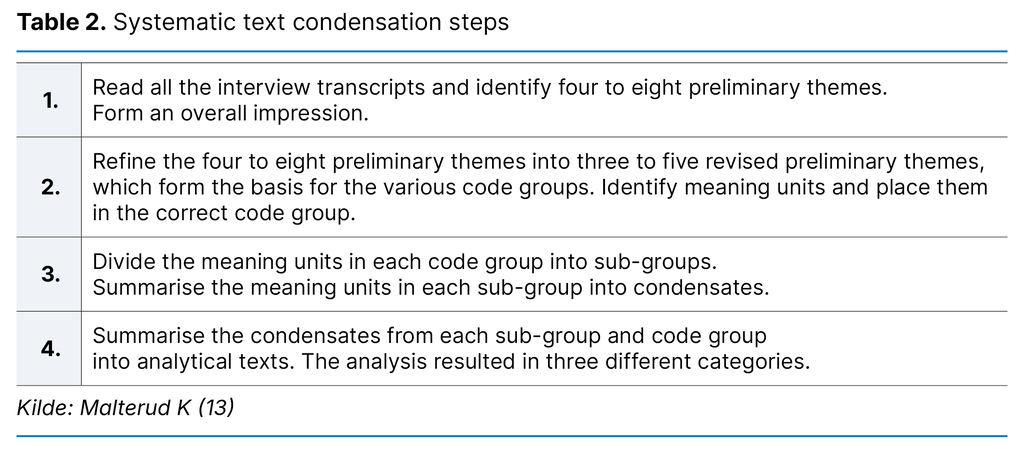

The results also showed that 45 of the MIPAC units often or always used fall risk scores for at-risk patients while 34 per cent never used this score. Scoring of nutritional risk was often or always used in 55 per cent of MIPAC units in Norway, while 23 per cent did not use such tools (Table 2).

Differences in systematic use of scoring tools across region and organisation

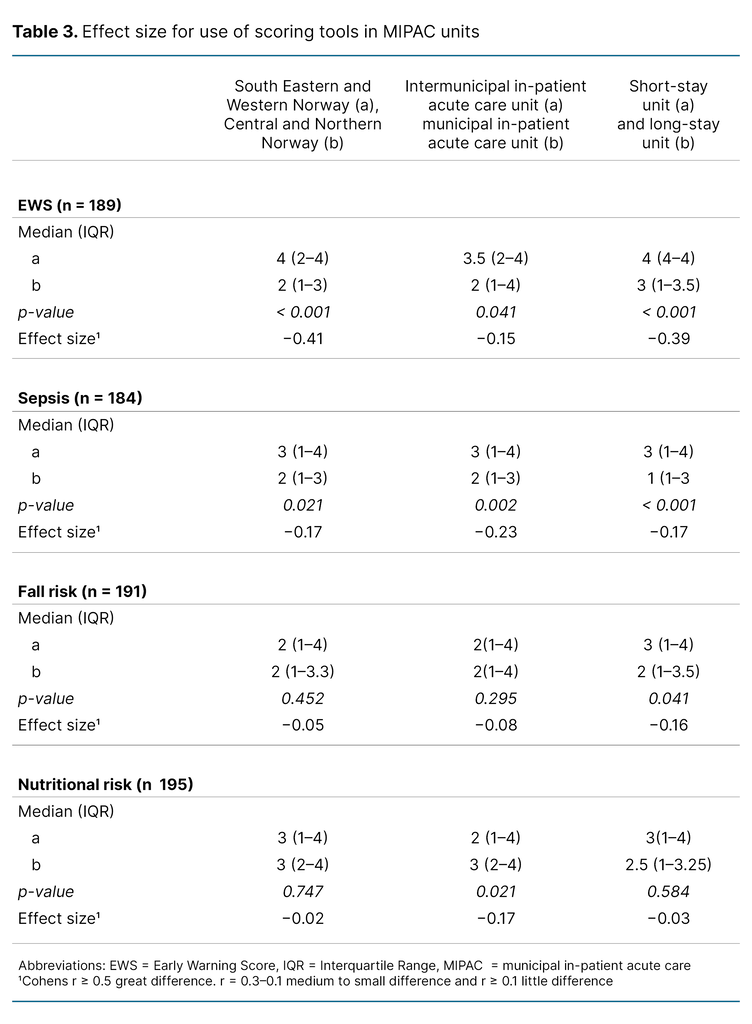

The results showed that EWS was used much more often in MIPAC units in South-Eastern and Western Norway than in Central and Northern Norway. EWS was more frequently used in MIPAC units organised under short-stay units than those organised under long-stay units.

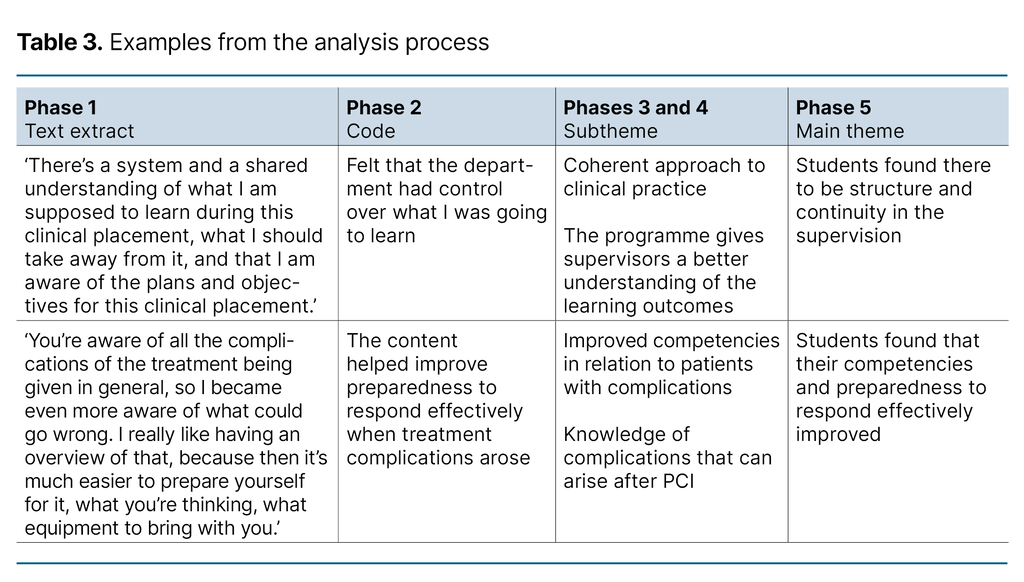

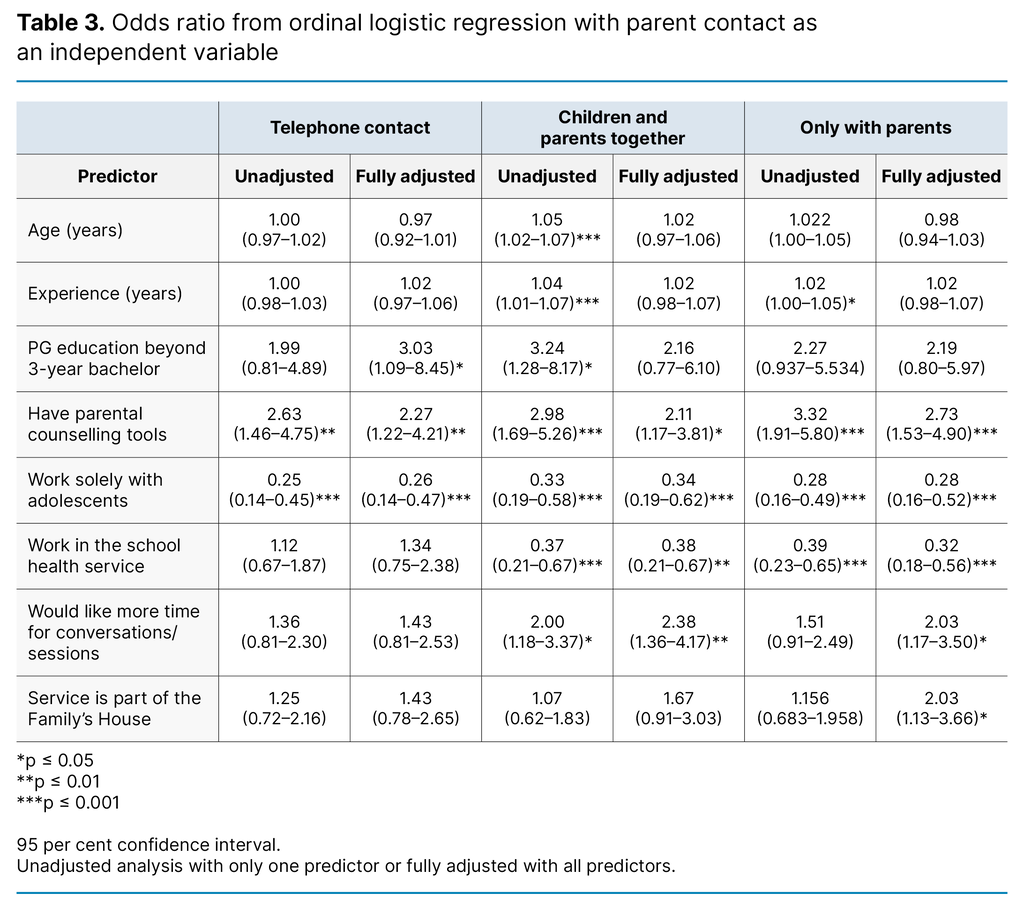

Moreover, we found that EWS was more frequently used in intermunicipal in-patient acute care units than in municipal units, but the differences were smaller. Sepsis scores were used slightly more often in South-Eastern and Western Norway compared with Central and North Norway. They were more often used in intermunicipal in-patient acute care units than in municipal units, and also more often in short-stay units than in long-stay units (Table 3).

Fall risk scoring tools were more frequently used for fall risk patients at short-stay MIPAC units than long-stay units. There were no significant differences in the use of fall risk scores either regionally or between intermunicipal and municipal units.

As regards the use of nutritional risk scoring tools, we found that they were more often used in municipal units than in intermunicipal units. There were no differences in their use regionally or between long-stay units and short-stay units.

Structural factors and variations in use of scoring tools in RNs’ decision-making processes

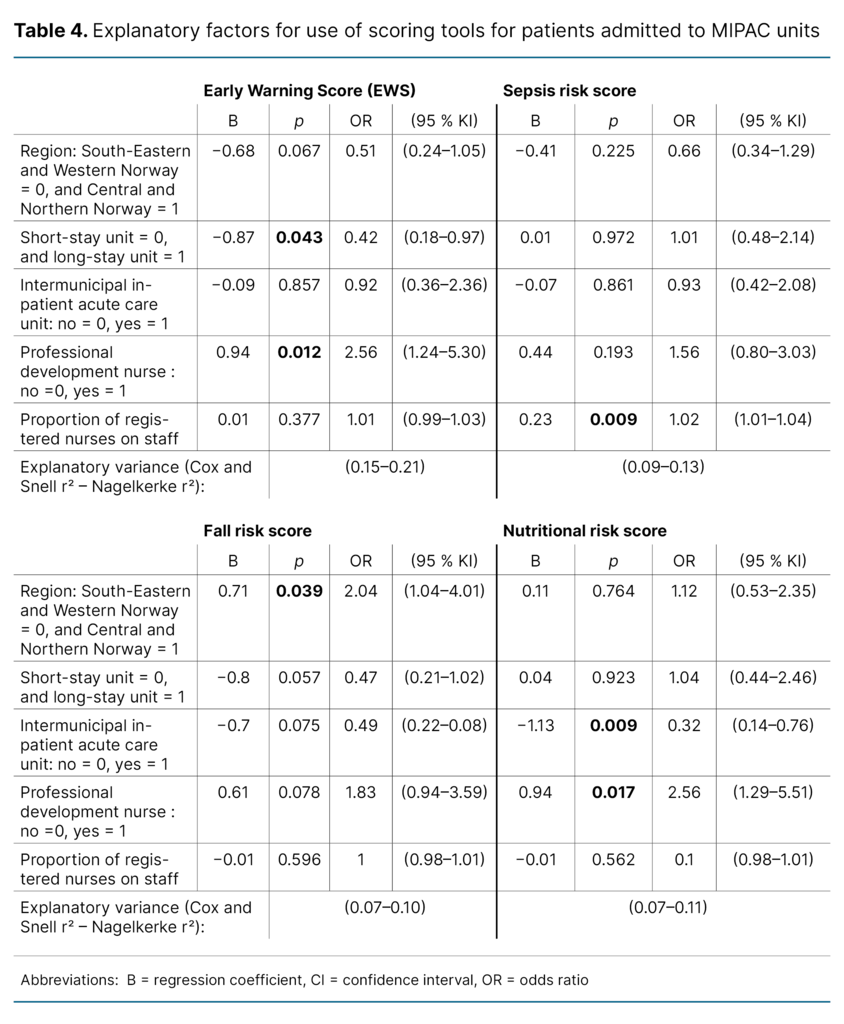

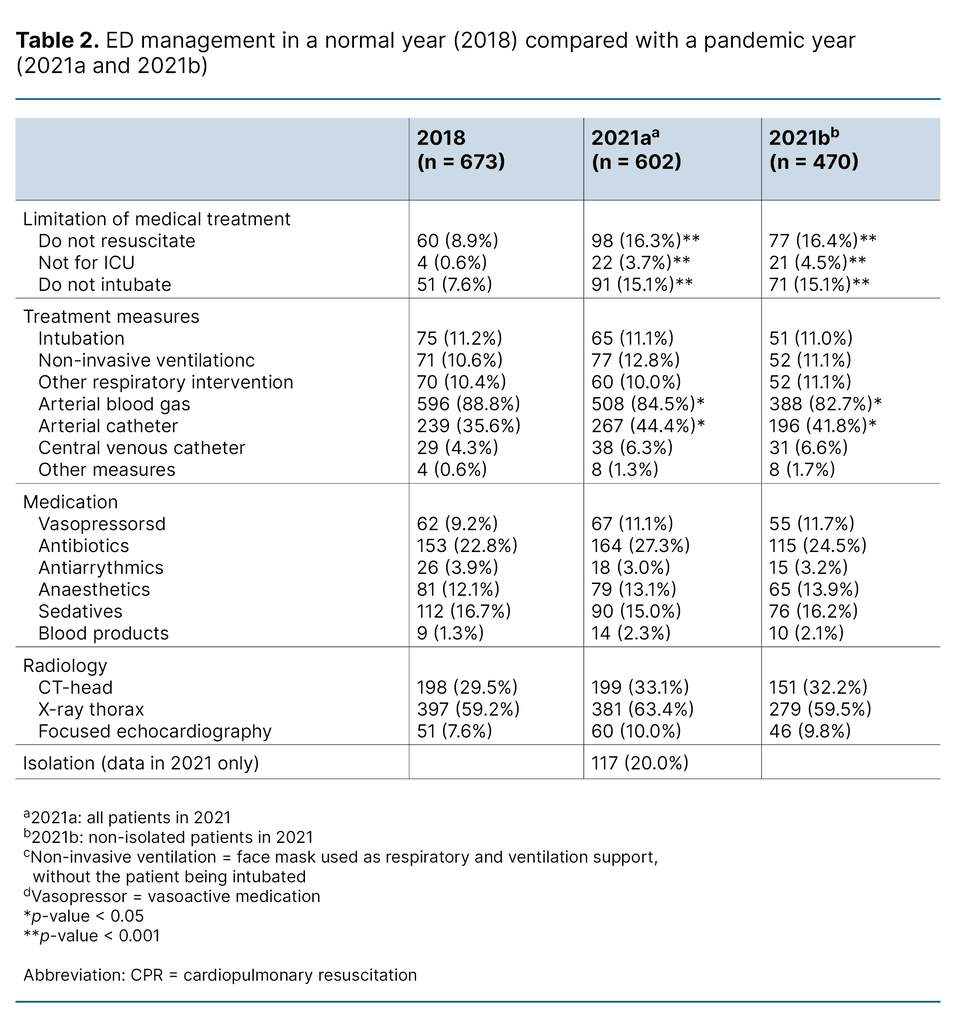

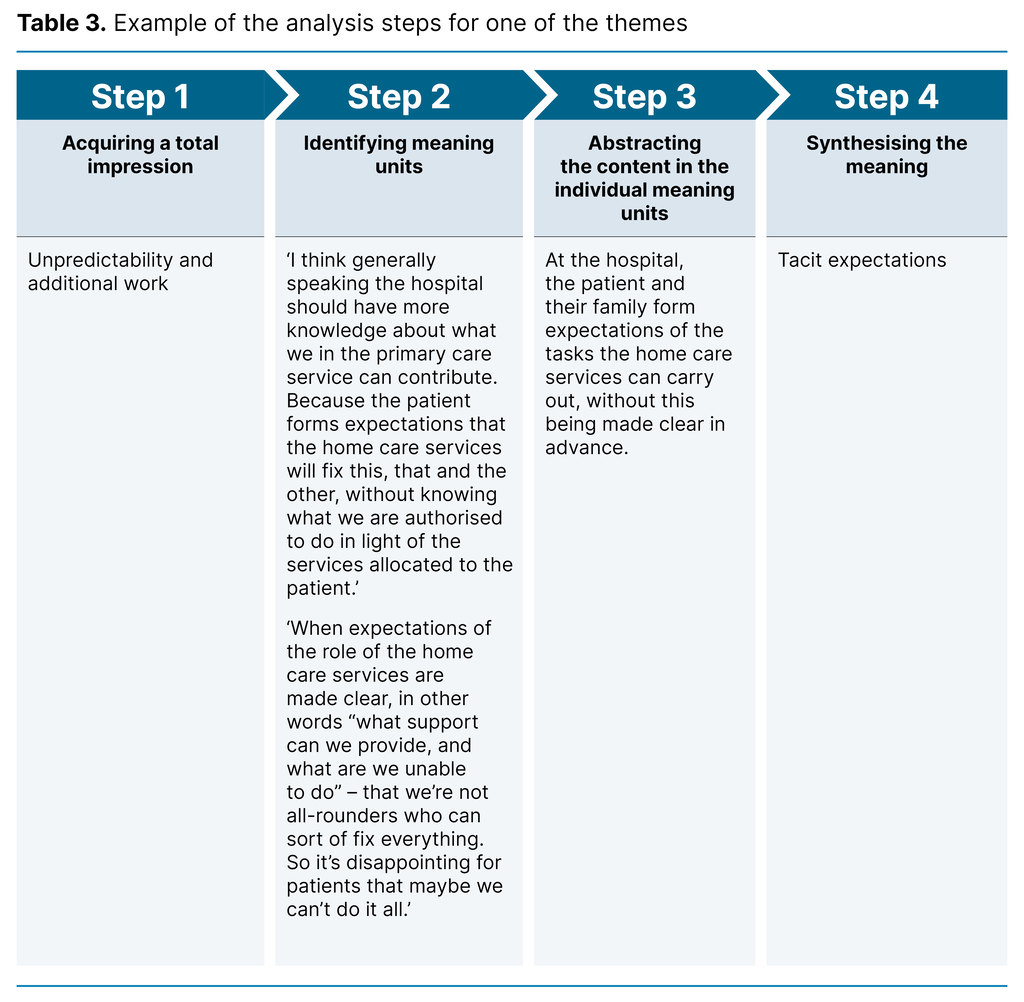

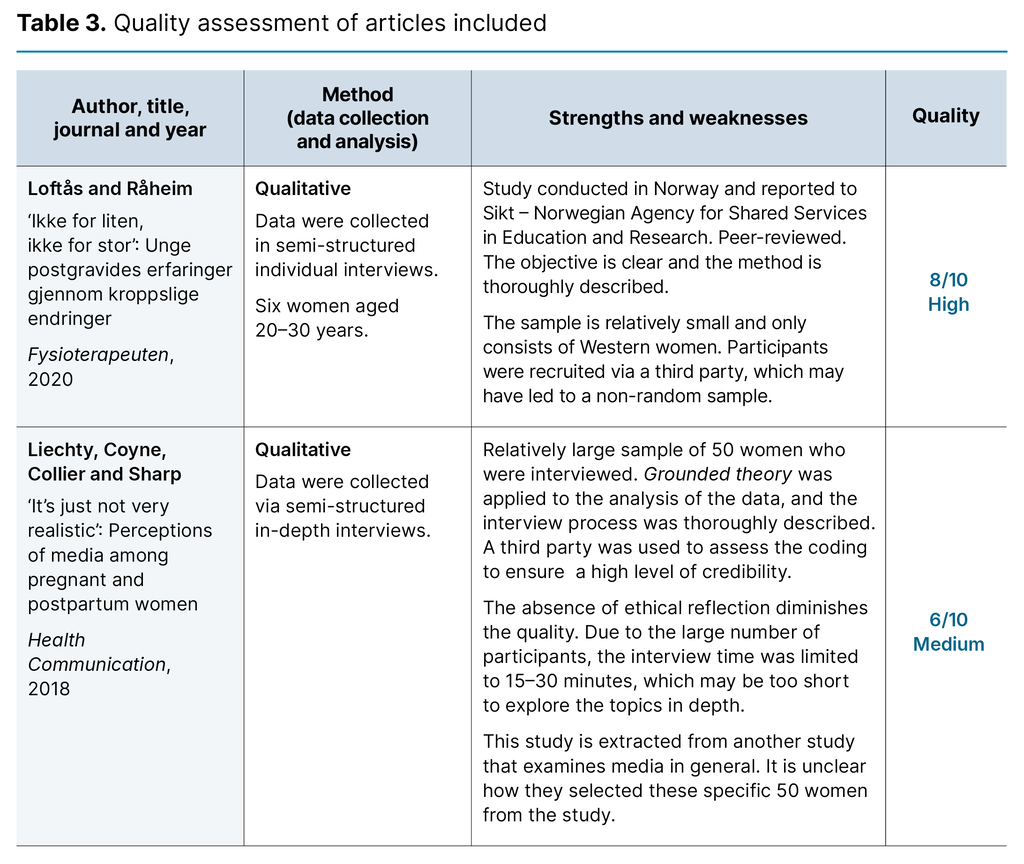

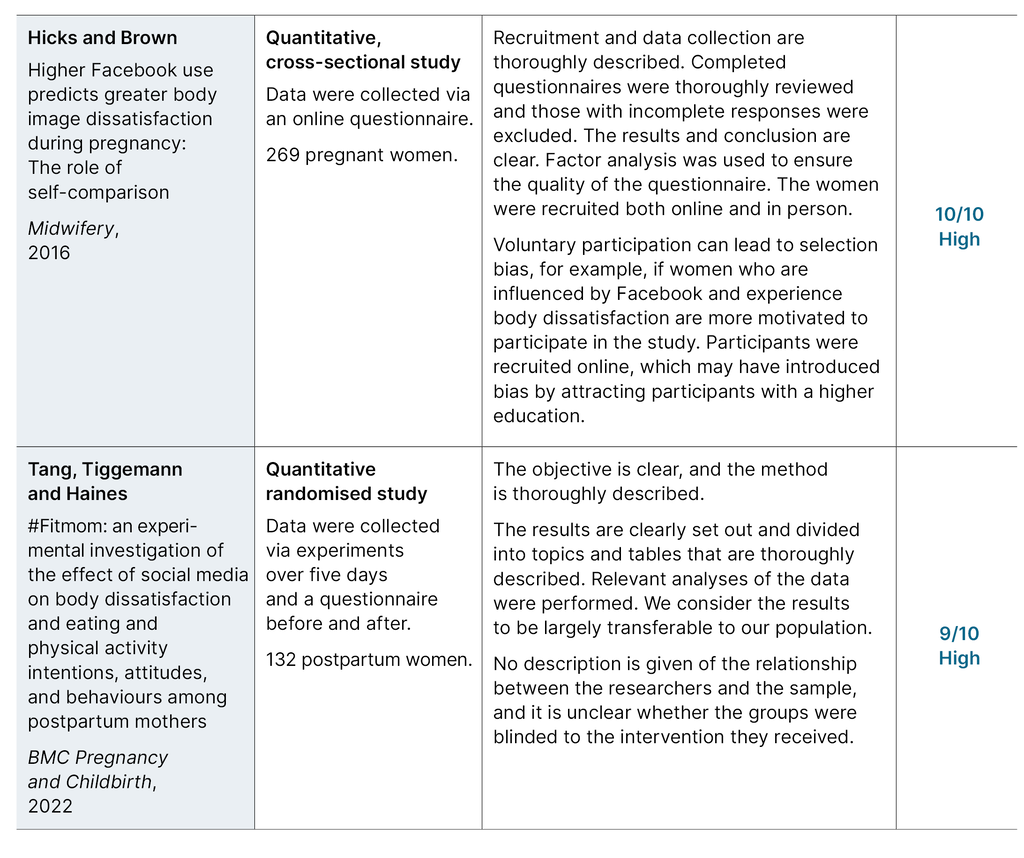

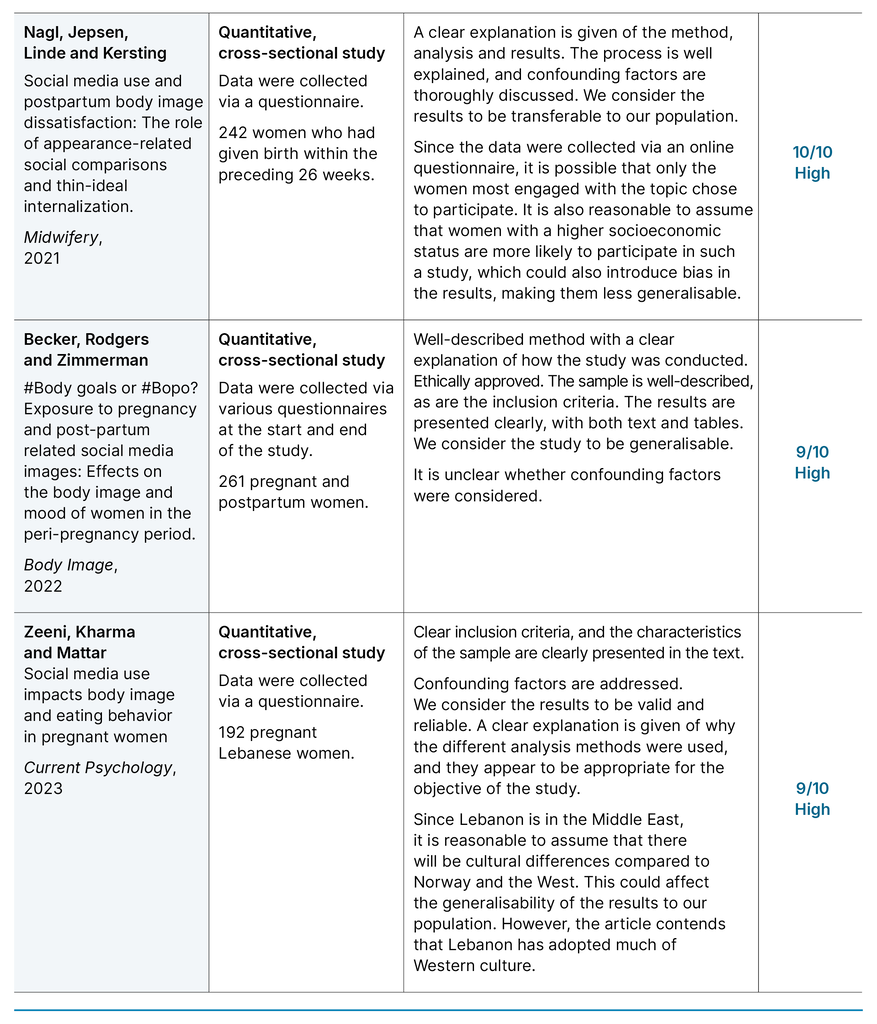

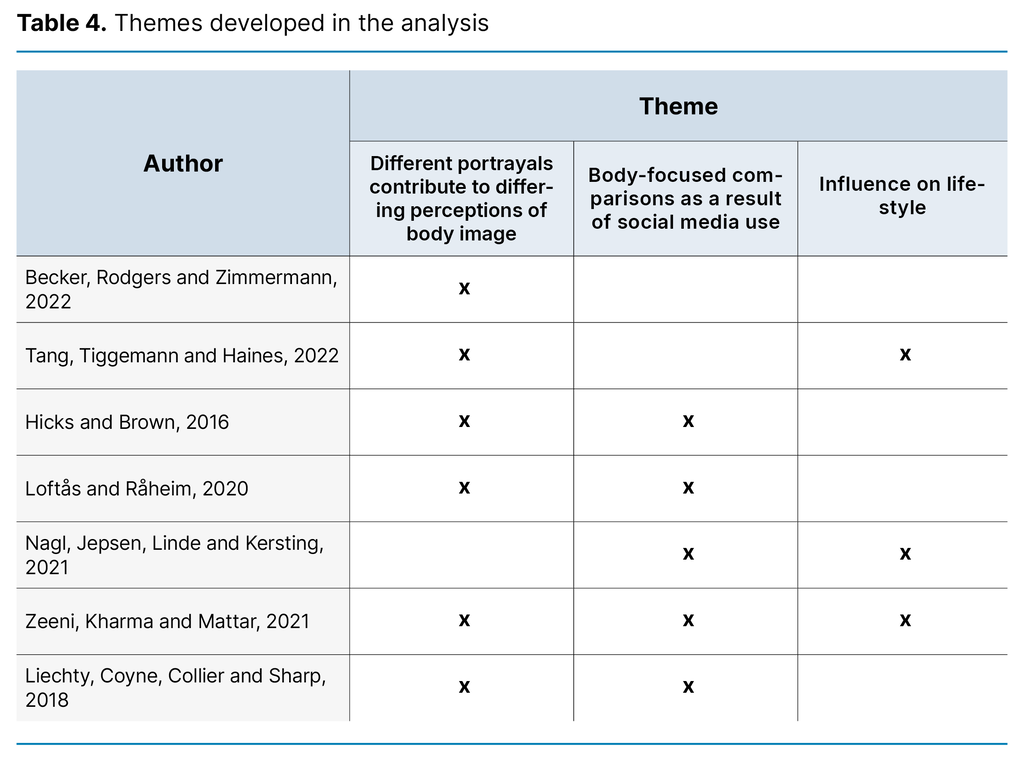

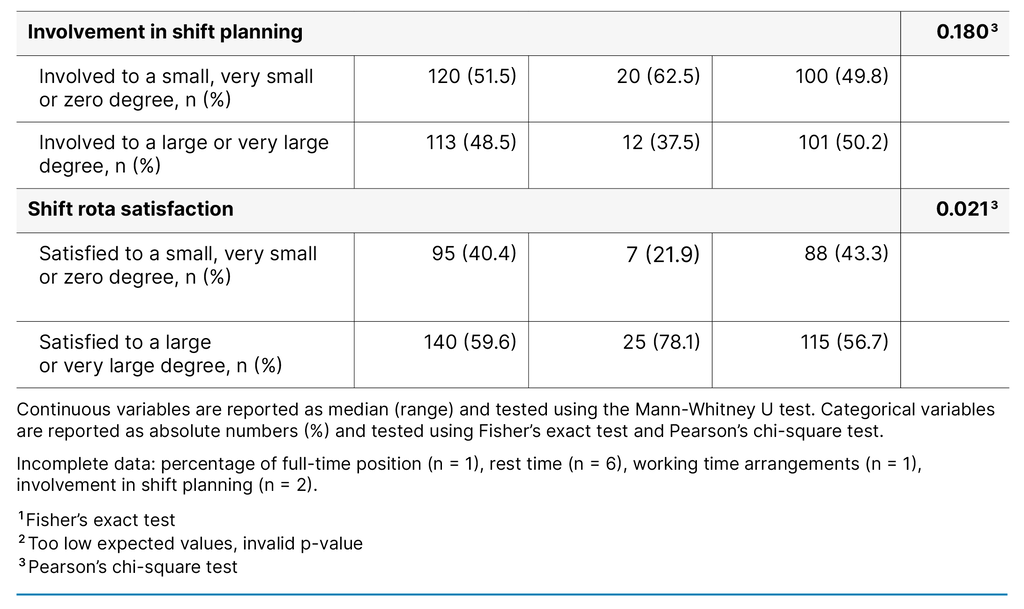

The regression model explained between 15 and 22 per cent of the variance in use of EWS, while the explanatory power was lower for sepsis scoring tools (9–13 per cent), fall risk (7–10 per cent) and nutritional risk (7–11 per cent) (Table 4).

The presence of a position for a professional development nurse in the unit was significantly associated with greater use of both EWS and nutritional risk scoring tools, with an odds ratio of 2.56. This means that the probability of using these scoring tools is over 2.5 times greater in units with a professional development nurse than in those that do not.

Moreover, a higher proportion of RNs on the staff was significantly related to greater use of sepsis scores, but the effect was relatively small (OR 1.02). However, this estimate indicates that if the percentage of RNs on the staff is increased by 10 per cent, in all likelihood the use of sepsis risk scoring tools will increase by 20 per cent.

In the case of MIPAC beds located in short-stay units and organised as an intermunicipal service, there was a negative association with the use of nutritional risk scoring tools (OR = 0.32). This demonstrates that such scoring tools are more frequently used in MIPAC units that are not part of an intermunicipal service.

In addition, we identified regional differences whereby the probability of using fall risk scoring tools in MIPAC services in Central and Northern Norway was twice as high as in South-Eastern and Western Norway (OR = 2.04).

Discussion

The main findings in this study show that less than half of the MIPAC units used scoring tools systematically to support RNs’ decision-making in clinical practice. Although EWS is the most frequently used scoring tool, one-third of the MIPAC units do not use it.

We also detected a geographical variation: EWS is used considerably less in Central and Northern Norway compared with South-Eastern and Western Norway. Fall risk and nutritional risk scoring tools are used systematically in approximately half of the MIPAC units.

Furthermore, the study revealed that structural framework conditions such as the presence of a professional development nurse play an important role in the use of scoring tools. The probability of using both EWS and nutritional scoring tools was over two and a half times greater in units with a professional development nurse than in units without.

These findings may indicate that there should be greater focus on the value of systematic use of scoring tools in clinical practice.

Use and variation in use of scoring tools in MIPAC services

The results of this study show that RNs in MIPAC services use scoring tools systematically to some extent or little extent as a decision-making tool in clinical practice. This is not in line with the health authorities’ recommendations (4, 5, 35). It appears that EWS is the most frequently used decision-making support tool of those examined in the study.

Our results indicate that EWS is used systematically in just over half of the Norwegian MIPAC units. National clinical guidance strongly recommends it as a tool for early detection and rapid response with regard to the deterioration of somatic conditions. It is crucial for ensuring patient safety, improving treatment results and reducing the risk of serious complications (5).

Therefore, the finding that approximately one-third of Norway’s MIPAC units do not appear to use scoring tools to detect early deterioration of somatic conditions is surprising. Infection symptoms are among the most common diagnoses on admission to MIPAC units and are difficult to identify at an early stage solely based on clinical judgement without systematic and objective observations. Many of the older patients admitted have unpredictable and complex health conditions (2, 3, 30).

Therefore, it is worrying that as many as one-third of the services have not implemented these systems in the municipality’s highest level of care for acutely ill patients. Infections can escalate quickly and develop into serious, life-threatening diseases if the correct medical treatment is not initiated in time (31).

Scoring tools also help ensure that communication between RNs and doctors is relevant and accurate, so that essential treatment can be initiated as early as possible. Effective and confident decision-making in clinical situations is linked to adequate communication and a common understanding of clinical terminology (5, 32).

In telephone communication between RNs and doctors, the precise and relevant information represented by EWS and sepsis scores is of decisive importance in ensuring rapid and appropriate medical treatment. In many of the municipal institutions with MIPAC services, a doctor is not always present so that out-of-hours medical services or the emergency medical assistance number 113 must be contacted (25).

The results show that sepsis risk scoring tools are used less than EWS. One explanation may be the finding in a 2016 study that EWS predicts serious illness more precisely than qSOFA. Consequently, the use of more traditional tools such as EWS was recommended (17). The Norwegian Directorate of Health’s current recommendations for sepsis treatment also state that qSOFA is not effective in detecting the development of sepsis and NEWS2 is therefore recommended (33).

A Norwegian doctoral thesis (30) points out that EWS tools have an important function in the municipal health and care services. They are effective in combination with clinical judgement in predicting clinical response and death (17). However, they are not applied entirely as intended because they are not adapted to the organisational structure or the older patient group (18, 19, 34).

As in hospitals, the organisational structure of MIPAC services is well adapted to the use of scoring tools to identify the exacerbation of somatic disorders and sepsis. If MIPAC units are to replace hospital treatment or offer as good quality services as hospitals, the use of EWS in 24-hour emergency units such as MIPAC units should be a minimum requirement.

The results showing less use of EWS and sepsis risk scoring tools in Central and Northern Norway as well as in long-stay units may be due to the lower proportion of RNs and doctors at units in these regions (24). Central and Northern Norway have fewer units with professional development nurse positions than South-Eastern and Western Norway.

However, previous research shows that the patient groups in the various MIPAC units varied considerably. Units with high nursing competence and good doctor coverage admitted a greater number of older patients with complex health conditions. Units with fewer resources had strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, and rejected patients if they could not give them proper care (34). This may explain why smaller MIPAC units find systems such as EWS and scoring tools less relevant.

Nevertheless, older patients with diffuse and subtle symptoms may be admitted to MIPAC units that do not have sufficient competence (3). Conditions that are not perceived as serious on admission can quickly deteriorate. For example, an infection may need to be identified at an early stage to prevent serious outcomes such as sepsis (5, 31). A complex clinical picture in older patients underlines the importance of offering adequate treatment at the correct level of care.

The fact that scoring tools are not used systematically can also be partly explained by how challenging it is to access competence and resources for professional development (23, 24). Moreover, health personnel do not always find the tools useful because they are not sufficiently well-adapted to the context or patient group (17, 19).

Our results show that fall risk and nutritional risk scoring tools were used systematically by approximately half of the MIPAC units. However, the results also demonstrate that a considerable number of units, one-third and one-fourth respectively, do not use these tools.

One possible explanation is that there may be different understandings of the responsibilities inherent in the mandate of MIPAC services, or that assessment of fall risk and nutritional risk are not regarded as relevant in emergency situations. If so, this is not in line with national clinical guidance on fall prevention in older patients (35) or national clinical guidelines for the prevention and treatment of undernutrition (4), where it is emphasised that early, systematic identification of risk is required.

The importance of structural factors for systematic use of scoring tools

The results show that structural framework conditions are associated with variation in the use of the scoring tools included in our study. The explanatory value is highest for the use of EWS and somewhat lower for sepsis, nutritional and fall risk scores. An interesting finding, nevertheless, is that the probability of using fall risk scoring tools is twice as great for MIPAC services in Central and Northern Norway.

This result may be due to the fact that a greater proportion of 24-hour emergency beds are located at long-stay units in Central and Northern Norway than in South-Eastern and Western Norway. This may mean that in long-stay units, the prevention of falls is prioritised and more often practised in long-stay units.

However, having a professional development nurse position in the unit emerges as the most important factor in our model. The odds of using EWS and nutritional risk score was over two and a half times greater in units with a professional development nurse. The results of the regression model indicate that the differences we found between municipal and intermunicipal in-patient acute care beds can probably be attributed to the fact that intermunicipal services had the advantage of better access to resources since several municipalities bear the costs (21).

This allows units to have a professional development nurse and more RNs on the staff. Overall, these results indicate that the following are vital for knowledge-based practice in MIPAC services: nursing competence, nurses with specialised education or master’s degree qualifications, and clinical development positions in line with national guidelines and advice.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A limitation of studies with a cross-sectional design is that they can only describe the actual situation at a particular point in time. Our study was based on data from 2019, and the situation may be different today. Introducing scoring tools means that work processes change, and both resources and time are required to implement changes in clinical practice. Consequently, the study may be relevant for current practice.

A strength of our study is that all MIPAC units are included in the sample, and the response rate is over 90 per cent. Even though we attempted to include all municipal in-patient acute care units, it was challenging to acquire a total overview because these municipal services constantly changed their location and organisation. Even though we made every attempt to include the whole population, some units may have been overlooked.

Conclusion

The study shows that the use of scoring tools in MIPAC services varies and that their systematic use in Norway is limited. In many units, the tools do not form part of RNs decision-making basis. The complex, unpredictable health of acutely admitted patients challenges RNs’ assessment and decision-making skills. Appropriate use of scoring tools can supplement nurses’ competence, and support quality and patient safety.

The target group for MIPAC services indicates that there is a need for scoring tools, both to identify life-threatening conditions at an early stage, and to detect the risk of falls and undernutrition in short- and long-term situations. The fact that these scoring tools are not used systematically in all MIPAC units represents a challenge to patient safety, and indicates that patients are subject to differential treatment depending on where they live.

Having a position for a professional development nurse can promote greater use of scoring tools in MIPAC services. More research is needed to understand the reasons for the variation in the use of scoring tools, and the possible consequences for patient safety when these are not used systematically.

The auhtors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

Many municipal in-patient acute care units do not use scoring tools as part of registered nurses’ decision-making basis.

Background: The clinical assessment and decision-making skills of registered nurses (RNs) face challenges in the encounter with patients with acute care needs referred to municipal in-patient acute care (MIPAC) services. The goal of these services is to provide care for older patients and those with chronic, complex health challenges. The use of decision-making tools is recommended to ensure high-quality treatment. However, knowledge of their practical application is limited.

Objective: We wished to explore the degree to which nurses at MIPAC services in Norway use scoring tools in their clinical decision-making processes for early identification of deteriorating somatic condition, risk of falls and risk of undernutrition.

Method: Cross-sectional study with a questionnaire distributed to 220 first-line managers in all of Norway’s MIPAC units.

Results: A total of 207 first-line managers (91.6 per cent) were included in the study. Some 57 per cent of the units examined used the Early Warning Score (EWS) systematically to identify deteriorating somatic condition at an early stage while 29 per cent of the units did not use this. The sepsis scoring tool recommended when the data were collected was systematically used in 46 per cent of the units, while 32 per cent did not use a sepsis score. The use of these tools was lowest in units in Central and Northern Norway and in MIPAC services co-located with long-stay care units. The scoring tool for identifying fall risk was systematically used in 45 per cent of the units, and the nutritional risk screening tool in 55 per cent of the units, while 34 per cent and 33 per cent respectively did not use the tools. Having a professional development nurse (often referred to in the literature as ‘clinical nurse educator’) attached to the unit was the most important factor in the use of the Early Warning Score and tools to assess nutritional status.

Conclusion: The study reveals that there is a considerable potential for increased use of scoring tools in MIPAC services in Norway. The results indicate that this can be achieved by strengthening clinical management through employing professional development nurses in the units.

Tredjeforfatternavn endret fra Mariann til Marianne (23.05.2025).

Tabell 3: Deltakertall fjernet for hver enhet for EWS, sepsis, fallrisiko og ernæring (12.09.2025).

Faktaboks: Overskrift endret fra "Skåringsverktøy for sepsis" til bare "Skåringsverktøy" (12.09.2025).

- Use of scoring tools for patients admitted to municipal in-patient acute care (MIPAC) units in Norway varies considerably.

- The use of scoring tools is related to geographical location and organisation of the service.

- Presence of a professional development nurse in MIPAC units may promote greater use of the Early Warning Score (EWS), nutritional risk score and fall risk score when assessing patients’ condition.

1. Sogstad M, Hellesø R, Skinner MS. The development of a new care service landscape in Norway. Health Serv Insights. 2020;13. DOI: 10.1177/1178632920922221

2. Hjertstrøm HK, Obstfelder A, Norbye B. Making new health services work: nurse leaders as facilitators of service development in rural emergency services. Healthcare. 2018;6(4):128. DOI: 10.3390/healthcare6040128

3. Vatnøy TK, Karlsen TI, Dale B. Exploring nursing competence to care for older patients in municipal in‐patient acute care: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(17–18):3339–52. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.14914

4. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for forebygging og behandling av underernæring [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2021 [cited 1 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/forebygging-og-behandling-av-underernaering

5. Helsedirektoratet. Tidlig oppdagelse og rask respons ved forverret somatisk tilstand [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2020 [cited 16 December 2024]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/faglige-rad/tidlig-oppdagelse-og-rask-respons-ved-forverret-somatisk-tilstand

6. Oliver D, Britton M, Seed P, Martin FC, Hopper AH. Development and evaluation of evidence based risk assessment tool (STRATIFY) to predict which elderly inpatients will fall: case-control and cohort studies. BMJ. 1997;315(7115):1049–53. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1049

7. Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2 [Internet]. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2017 [cited 1 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-early-warning-score-news-2

8. Timmermans S, Epstein S. A world of standards but not a standard world: toward a sociology of standards and standardization. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36(1):69–89. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102629

9. Banning M. A review of clinical decision making: models and current research. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(2):187–95. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01791.x

10. Odell M, Victor C, Oliver D. Nurses’ role in detecting deterioration in ward patients: systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(10):1992–2006. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05109.x

11. Higgs J, Jones MA, Loftus S, Christensen N. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008.

12. Downey CL, Tahir W, Randell R, Brown JM, Jayne DG. Strengths and limitations of early warning scores: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int. J Nurs Stud. 2017;76:106–19. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.09.003

13. Karlsen EE, Rønsåsbjørg NA, Skrede S, Mosevoll KA. Skåringsverktøy for tidlig oppdagelse av sepsis på sengepost. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2023;143. DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.21.0905

14. Gjerlaug AK, Harviken G, Uppsata S, Bye A. Verktøy ved screening av risiko for underernæring hos eldre. Sykepl Forsk. 2016;11(2):148–56.

15. Olsen RM, Ness TM, Devik SA, Senter for omsorgsforskning. Fall og pasientsikkerhet blant eldre i kommunene – en oppsummering av kunnskap [Internet]. Omsorgsbiblioteket; 2017 [cited 15 May 2025]. Available from: https://omsorgsforskning.brage.unit.no/omsorgsforskning-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2452445/Fall%20og%20pasientsikkerhet.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

16. Churpek MM, Yuen CT, Winslow PC, Hall PJ, Edelson PD. Differences in vital signs between elderly and nonelderly patients prior to ward cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):816–22.

17. Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, Sokol S, Pettit N, Howell MD, et al. Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the Intensive Care Unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;195(7):906–11. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0854OC

18. Jeppestøl K, Vitelli V, Kirkevold M, Bragstad LK. Factors associated with care trajectory following acute functional decline in older home nursing care patients: a prospective observational study. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2022;34(1):42–51. DOI: 10.1177/10848223211034774

19. Jeppestøl K, Kirkevold M, Bragstad LK. Early warning scores and trigger recommendations must be used with care in older home nursing care patients: results from an observational study. Nurs Open. 2023;10(7):4737–46. DOI: 10.1002/nop2.1724

20. St.meld. 47 (2008–2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid [Internet]. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2009 [cited 1 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/d4f0e16ad32e4bbd8d8ab5c21445a5dc/no/pdfs/stm200820090047000dddpdfs.pdf

21. Arntsen B, Torjesen DO, Karlsen T-I. Drivers and barriers of inter-municipal cooperation in health services – the Norwegian case. Local Gov Stud. 2018;44(3):371–90. DOI: 10.1080/03003930.2018.1427071

22. Helsedirektoratet. Kommunenes plikt til øyeblikkelig hjelp døgnopphold. Veiledningsmateriell [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2016 [cited 1 July 2024]. Available from: https://helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/kommunenes-plikt-til-oyeblikkelig-hjelp-dognopphold-veiledningsmateriell

23 Vatnøy TK, Dale B, Skinner MS, Karlsen TI. Associations between nurse managers’ leadership styles, team culture and competence planning in Norwegian municipal in‐patient acute care services: a cross‐sectional study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2022;36(2):482–92. DOI: 10.1111/scs.13064

24. Vatnøy TK, Skinner MS, Karlsen T-I, Dale B. Nursing competence in municipal in-patient acute care in Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):1–11. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-020-00463-5

25. Skinner MS. Døgnåpne kommunale akuttenheter: en helsetjenestemodell med rom for lokale organisasjonstilpasninger. Tidsskr Omsorgsforsk. 2015;1(2):131–44. DOI: 10.18261/ISSN2387-5984-2015-02-09

26. Helsedirektoratet. Øyeblikkelig hjelp døgntilbud i kommunene. Status 2019 [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 12 June 2019 [updated 22 September 2023; cited 1 July 2024]. IS-2941. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/status-for-oyeblikkelig-hjelp-dogntilbud/Status%20for%20kommunalt%20døgntilbud%20for%20øyeblikkelig%20hjelp%202019.pdf?download=false

27. Helsedirektoratet. Status for kommunalt døgntilbud for øyeblikkelig hjelp 2022 [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2023 [cited 1 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/status-for-kommunalt-dogntilbud-for-oyeblikkelig-hjelp-2022

28. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Fortaleza: World Medical Association; 2013.

29. Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141(1):2. DOI: 10.1037/a0024338

30. Jeppestøl K. Acute functional decline in older home nursing care patients: using the Modified Early Warning Score to support clinical reasoning and decision-making in community care. A mixed methods study [doctoral thesis]. Oslo: University of Oslo; 2023.

31. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

32. Radhakrishnan K, Jones TL, Weems D, Knight TW, Rice WH. Seamless transitions: achieving patient safety through communication and collaboration. J Patient Saf. 2018;14(1):e3–5. DOI: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000168

33. Helsedirektoratet. Sepsis [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2020 [updated 14 February 2025; cited 2 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/antibiotika-i-primaerhelsetjenesten/andre-infeksjoner/sepsis#69be96f4-f994-4ecb-a822-bf69c3a5c737-praktisk-informasjon

34. Jeppestøl K, Kirkevold M, Bragstad LK. Assessing acute functional decline in older patients in home nursing care settings using the Modified Early Warning Score: a qualitative study of nurses’ and general practitioners’ experiences. Int J Older People Nurs. 2021;17(1):e12416. DOI: 10.1111/opn.12416

35. Yang F, Skinner MS. HSD4 institutional and geographical variation in discharge destination among admission avoidance municipal inpatient acute care units in Norway. Value in Health. 2023;26:S294. DOI: 10.1016/j.jval.2023.09.1556

36. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonale faglige råd [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2024 [cited 1 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/faglige-rad/fallforebygging-hos-eldre