Experiences with combining work and caregiving when a partner is seriously ill with cancer

Summary

Background: Research shows that it can be challenging for partners of seriously ill cancer patients to continue working and/or perform their duties in the workplace satisfactorily because of the increased responsibilities at home in the caregiving role. There is a lack of qualitative research that highlights the partners’ experiences with balancing their caregiving responsibilities and their work.

Objective: We aimed to explore the experiences of surviving partners of cancer patients. The most interesting aspect was their experiences of the caregiving role while in work.

Method: Our study had a qualitative design and we conducted 11 individual in-depth interviews with respondents from the Norwegian Cancer Society’s user panel. The respondents included were surviving partners (cohabitant or spouse) of cancer patients, who continued to work during their partner’s illness. As a methodological tool, we used thematic analysis – a method for identifying, analysing and describing patterns in qualitative data.

Results: We identified three main themes: 1) Work limitations, 2) Joy from continuing to work and 3) Caring for partner while continuing to work. Participants faced various limitations that made it challenging to fully participate in the workforce. They also noted that it was important to be able to work in order to recharge and have a break. Few respondents mentioned financial problems, but several criticised current financial and non-financial support schemes. They stressed the importance of being able to care for and support their partner in practical and psychosocial terms, and in dealing with the health service.

Conclusion: The descriptions in our study align well with previous findings: continuing to work while acting as a caregiver is complicated. While it is important to have a job to go to, many found that being there for their partner was even more valuable. However, many had a difficult time after their partner’s death, and several expressed a need for support schemes that were not available.

Cite the article

Taslidza I, Myhre G, Grov E, Syse A. Experiences with combining work and caregiving when a partner is seriously ill with cancer. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(98417):e-98417. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.98417en

Introduction

In a cancer pathway, it is not only the patient who is affected, but also those close to them (1). The partner is an important resource and, in many cases, takes on increased responsibility and more caregiving tasks (2–4). Tasks can be related to practical, emotional, physical and/or social aspects, and some could have been performed by healthcare personnel (5).

A study shows that caregiving tasks at home can take up to 20 hours per week, such as practical chores and follow-up on doctor appointments (6). Some tasks can cause stress and be so demanding that they have an adverse effect on the caregiver’s own quality of life (7–9). However, many describe the caregiving role as meaningful and report that it strengthens their bond with the person who is ill and brings them closer (10).

Nevertheless, the caregiving role can also affect their ability to work (11, 12), i.e. their self-assessed ability to perform job tasks as required (13). Many family caregivers therefore face challenges in balancing their working life with caregiving duties at home (1, 8, 11, 12).

The Norwegian Directorate of Health’s Family Caregiver Survey shows that one-third of the working population have been negatively affected by caregiving, with reduced efficiency, productivity and concentration (4). This finding is also confirmed in a US study, where one in three family caregivers of a cancer patient had to leave their job due to the strain (14).

Changes in employment can lead to changes in finances (1, 14–16). Meanwhile, the workplace and colleagues can help an employee maintain their identity, social network and ‘normal’ daily life (10). Consequently, a family caregiver’s job can serve as a sanctuary and an important arena for their social life (4, 17).

The employer’s sympathy for the family caregiver’s situation and ability to make accommodations are important factors that can help caregivers to continue working (10, 18–20).

Studies show that family caregivers with jobs that offer flexibility and accommodations are more likely to continue working and experience less stress (18–21). However, a Norwegian study shows that only one in four employers have procedures for supporting employees in caregiving situations (22).

The Norwegian health and welfare services have developed several support schemes to assist family caregivers (23) but few are aware of what is available (13). Care allowance is a little-used financial support scheme for family caregivers, designed to replace lost wages for up to 60 days’ absence from work (1). The scheme enables family caregivers to stay home and care for their loved one, but the financial support is terminated if the patient is admitted to an institution. The extent of family caregivers’ sick leave in Norway is unknown (21).

According to Norway’s National Insurance Act, sick pay is only for those who are unable to work due to a disability that is clearly due to their own illness or injury. ‘Incapacity for work caused by social or financial problems’ is not grounds for sick pay (24, section 8-4).

Objective of the study

Overall, there is very little Norwegian research on partners’ experiences of caregiving for a spouse/cohabitant with cancer while continuing to work (21). The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of surviving partners of cancer patients, with a particular focus on how it felt to be in a caregiving role while continuing to work.

Method

We employed a qualitative design in this study and conducted individual in-depth interviews using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1 – in Norwegian). The article is part of a larger project at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health on how cancer affects families, called Cancer in Families (FAMCAN).

Recruitment, inclusion criteria and sample

The participants were recruited from the Norwegian Cancer Society’s user panel. In January 2024, the Norwegian Cancer Society distributed an electronic survey. Recipients who met the pre-specified inclusion criteria were asked to leave their contact information for the research team.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: at the time of interview, participants must have had a partner who had recently died from cancer, participants were of working age and in employment. The Norwegian Cancer Society reviewed the responses and then forwarded the email addresses and phone numbers of 12 eligible participants to FAMCAN’s project manager.

The information was shared with the first two authors, who then contacted the individuals to provide more details about the study and ask them to participate. One person chose not to participate, but the remaining 11 consented. The interviews were arranged over the phone.

Data collection

The participants were spread across a large geographic area in Norway in six different counties. Seven interviews were conducted remotely via Teams, two were by phone and two were held in person in February 2024. The conversations lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, and audio recordings were made.

We used a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1 – in Norwegian), which was devised in a collaboration between the Norwegian Cancer Society, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University. The interview guide consisted of pre-defined questions and was structured based on the objective of the study, existing research and the researchers’ professional experience. FAMCAN’s users provided feedback on the interview guide.

The first two authors were present at all the interviews and alternated as moderators. This ensured that all topics were covered and that both could contribute with follow-up questions to gain a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences. The subsequent discussion on the findings also contributed to reflection and intersubjectivity, meaning relative agreement on how the participants described their experiences.

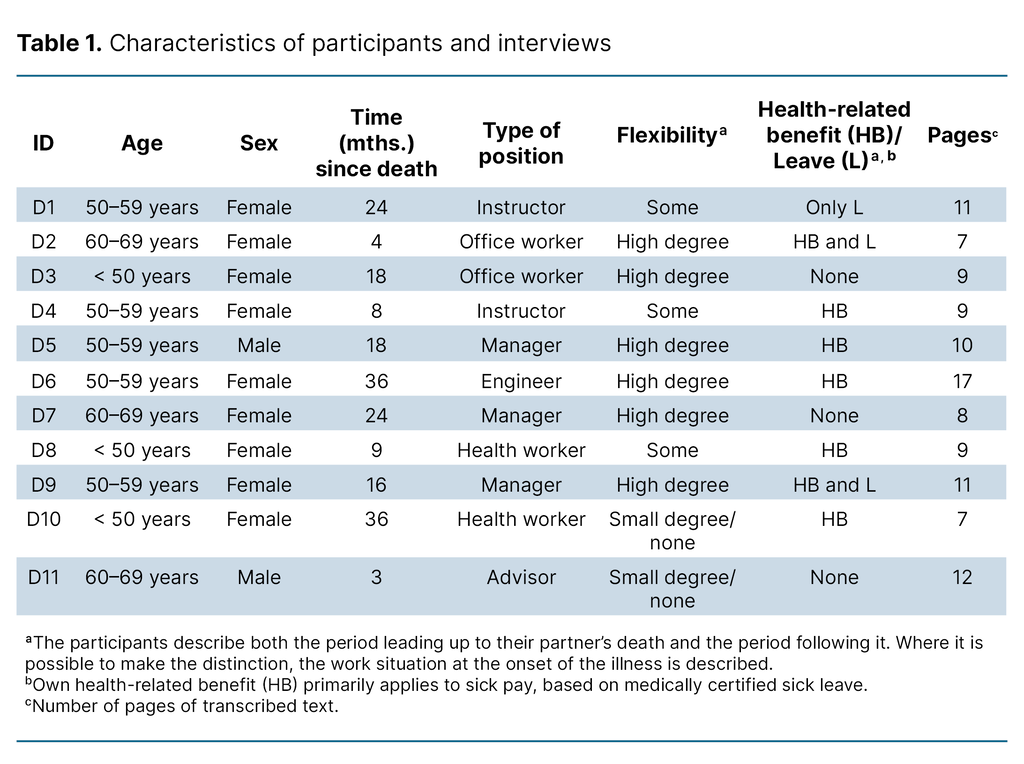

Table 1 gives a brief description of the informants. The time from the partner’s death to the interview varied from about three months to three years.

Data analysis

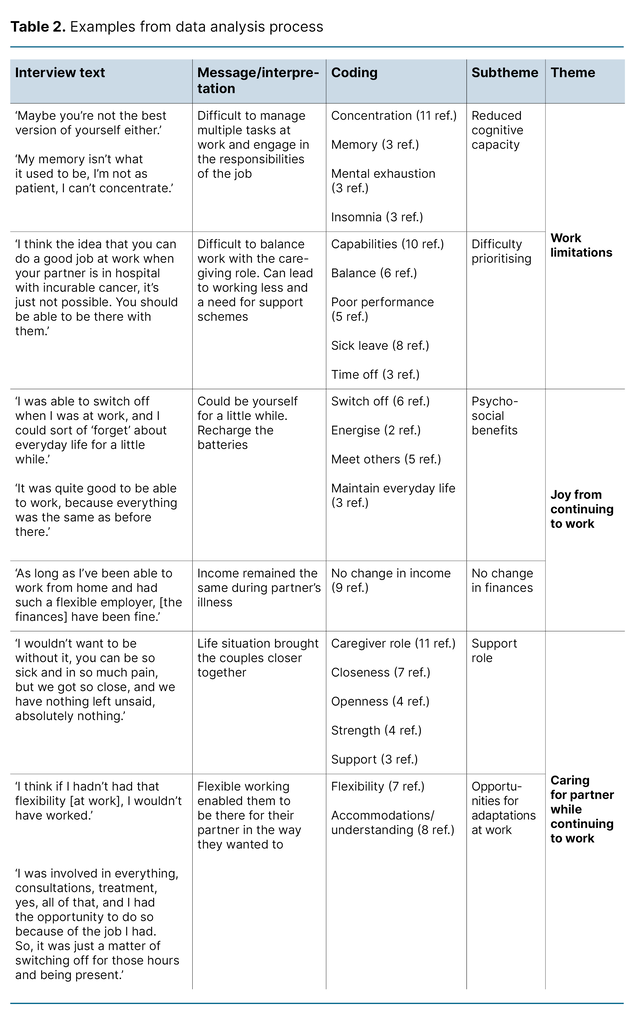

We employed Braun and Clarke’s six-step reflexive thematic analysis to analyse the data (25, 26). In the first step, the audio recordings were reviewed and manually transcribed by the first authors, giving a total of 110 pages. All transcriptions were read thoroughly by all the authors to familiarise themselves with the data. In the second step, we organised the data into codes (N = 23).

This led us to the third step in the analysis process: development of themes (Table 2). Codes that were similar to each other were grouped together. The themes were developed based on patterns in the data, such as similarities, differences, frequency and correspondence, but also based on the authors’ background understanding and experiences from the interviews.

In the fourth step, the themes and subthemes were redefined and discussed repeatedly in light of the codes from step two. Finally, the themes were defined and named (fifth step) and then presented in the results chapter (sixth step).

Ethical considerations

The project was reported to Sikt – Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number 907772/24). It did not need to be reviewed by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) because we did not use information about third parties or health data. The study therefore fell outside the scope of the Health Research Act. We conducted a risk and vulnerability analysis (RVA).

Audio recordings were stored in an encrypted format for 90 days using the data collection tool Nettskjema, and then deleted. We immediately de-identified the data and subsequently anonymised them in order to protect confidentiality and safeguard data protection. During transcription, participants’ dialects were transcribed into standard Norwegian (bokmål) to prevent the data from being recognisable. Ordinary personal information and anonymised transcriptions were stored with a key password in a dedicated project area in the Services for Sensitive Data (TSD) at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

We initially provided written information about consent to participate in an information letter. We then repeated this orally before the interview. Participants were informed about their right to withdraw, according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (27). Participants’ oral consent was thus given in the audio recording.

To protect those who were potentially in a vulnerable situation, we chose to recruit participants whose partner had already died (retrospective perspective). Some of the questions were nevertheless distressing as the participants had to relive difficult situations to answer them. We made it clear that they could choose not to answer certain questions, and request a break or withdraw without consequence.

Results

Our main findings were that many participants experienced (1) work limitations due to having a seriously ill partner. However, several of them emphasised (2) the joy (and benefit) of continuing to work while (3) acting as a family caregiver.

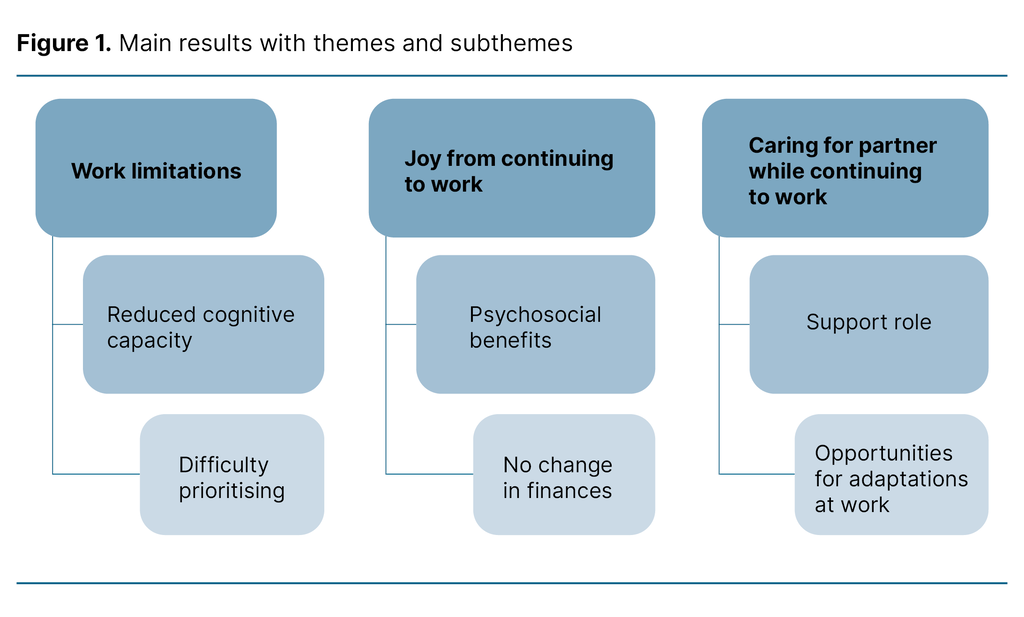

The interviews revealed that the majority found it challenging to work while in the caregiving role. They noted that workplace flexibility and accommodations were crucial for them being able to continue working while caring for and supporting their partner. Working was important because it gave the participants the opportunity to switch off and recharge. Figure 1 illustrates the main results and shows themes and subthemes from the analysis.

Reduced ability to work and difficulty prioritising

The majority of participants reported a reduced cognitive capacity, which led to limitations in their work capacity, including difficulty concentrating. They forgot things more often and felt more tired:

‘My memory isn’t what it used to be, I’m not as patient, I can’t concentrate, I’m a lot slower at things, it’s harder to get going.’

Many participants also found it challenging to set priorities. They had an internal struggle in the face of expectations, both at work and at home. The dynamics at home affected their ability to perform tasks at work, and vice versa, making the balancing act very difficult in some cases:

‘No, it wasn’t easy to balance things, to be really positive, encouraging and cheerful. I didn’t manage to balance it or keep my head above water.’

They found it challenging to combine work with caregiving tasks at home, both practically and mentally. Three participants expressed it as follows:

‘There aren’t enough hours in the day, and maybe you’re not the best version of yourself either. When you need more energy, more calm, and more understanding for your husband and children, you don’t have it.’

‘But I wasn’t sure how things were going at home when I was at work.’

‘I used to have everything under control, but that’s not always the case now.’

It became more difficult for participants to manage their duties at work and perform satisfactorily. This was often related to their partner’s health and the extent of their caregiving tasks. Many had to scale back their work commitments by working fewer hours, taking time off or taking sick leave. In the early stages of their partner’s illness, this particularly applied to participants in jobs with fixed working hours and few opportunities for flexibility.

In the later stages, many more reduced their working hours. Some felt that the sick leave system worked well, while others expressed a desire for a different arrangement because they themselves were not actually ill:

‘I wish there was something that said, ‟If you are in this extreme situation, you could get something that is not sick leave”. Because I’m not sick, I wasn’t sick, but I wasn’t functioning well.’

Two participants had fixed working hours (see Table 1) and had to change their work situation. They faced financial challenges both during and after their partner’s illness. Several applied for a care allowance but found that the payments stopped once their partner was hospitalised. The system was perceived as rigid and inadequate for dealing with the unpredictable nature of illness:

‘I think it’s a paradox, with the welfare state we live in, and such good systems for all sorts of things, I think the idea that you can do a good job at work when your partner is in hospital with incurable cancer, it’s just not possible. You should be able to be there with them.’

Psychosocial and financial benefits of continuing to work

Working was extremely valuable for the majority of our participants. At work, the family caregivers could be themselves for a short time. They could talk to colleagues about other things and take a break from their caregiving role and their partner’s illness. For some, physically being at work and receiving support from colleagues became important:

‘I was able to switch off when I was at work, and I could sort of ‘forget’ about everyday life for a little while. It allowed me to regain some energy and strength. It was like I had recharged my batteries in a way.’

Another benefit of continuing to work during their partner’s illness was that their finances and income remained unchanged. This applied to a total of nine participants.

Caring for partner while continuing to work

Participants in more flexible jobs felt supported and received understanding from their employers. They were given a great deal of freedom and extensive accommodations were made, such as working from home more often or flexible working hours, with the ability to log on and off as needed:

‘My employer [is] amazing. I could take time off and just let them know. And as [x] got worse, I was also granted leave to stay home.’

Many emphasised that workplace accommodations and flexibility made it possible to provide care at home while still carrying out some of their duties at work:

‘Given the job I have, I could be at home a lot more than perhaps others whose partners have cancer.’

Discussion

This study examines the experiences of surviving partners of cancer patients. The study also explores their experiences of acting as a family caregiver while continuing to work.

Importance of workplace flexibility and the joy of working

Our findings show that employees’ ability to work is impaired when they have a sick partner. They feel it is more difficult to work effectively. Their mental capacity in particular is reduced, which aligns with previous research (7, 8, 14, 15). Several participants reported feeling tired and being torn between being a good partner and a productive employee, in line with the key findings of the Family Caregiver Survey (4).

Participants with considerable workplace flexibility and/or accommodations were more likely to work almost normally, at least in the early stages of their partner’s illness. They reported being better able to manage their work tasks because they had the flexibility to choose when and where to complete them. This finding is consistent with previous research, which shows that flexibility increases the likelihood of family caregivers continuing to work (18, 19).

Flexibility also helped several participants manage both their caregiving role and their responsibilities as employees. Many expressed that workplace flexibility meant they could be involved in the medical follow-up of their partner’s illness, such as attending doctor’s appointments, which was in line with other findings (20).

This argument is further supported by the fact that participants without flexible workplaces had to reduce their working hours, take sick leave or take time off because they were unable to manage both home and work responsibilities. They were unsure whether sick leave was a good solution, as they were not necessarily the ones who were ill. Studies show that this type of sick leave is often based on a mental health diagnosis (28).

It was also problematic for several participants who used up their sick leave when their partner was sick and were left without any when they became ill themselves after their partner died.

In line with previous findings (4, 17), participants valued having a job as it meant they could get a break. Previous research (17) also shows that the workplace can serve as a sanctuary for self-care, maintaining a social network and an opportunity to get some breathing space. Having some time away from their partner also enabled them to contribute more in their caregiving role. A previous study showed that family caregivers who did not work were more stressed than those who did work (18). This finding corresponds with the experiences of participants in our study who had little or no workplace flexibility and who reported a greater extent of physical and mental strains.

The finances of the majority of participants were unaffected. This finding does not fully align with previous research (1, 14–16). Our sample predominantly described having a flexible work situation (Tables 1 and 2). It is possible that those with less flexible work situations might have responded differently. Future research should consider prospective designs and registry data in order to include a representative sample of partners with flexible and less flexible jobs.

Care tasks and perceptions of support

The health service should have guidelines for protecting and supporting family caregivers (23), but half of these caregivers spend considerable time performing and/or coordinating services (4). Family caregivers are entitled to help at home, such as technical aids, practical assistance or healthcare services in addition to respite care (29).

We found that caregivers described the experience of spending time with their partner as invaluable as it brought them closer together. This is in line with previous research (6). However, many faced challenges when their partner had significant care needs. Participants described situations where they helped with tasks such as personal care, nursing and mobilisation. For some, it became difficult to leave the house because they had to stay with their partner.

Several participants called for more support and welfare schemes to manage the daily life of being both an employee and a family caregiver. Guidance from healthcare personnel can help prevent additional stress for caregivers (23, 30), such as on techniques for moving patients, nutritional advice, or emotional support (30–33). The latter is particularly important for nurses who interact with family caregivers (34), but many of our participants felt that the clinical nurses and cancer coordinators were often unavailable due to high workloads.

We asked participants specifically about the care allowance scheme in the interviews. Participants had either heard about the scheme through an acquaintance or found information about it online, but it was often discovered too late, as was found in earlier studies (1). Participants who received the care allowance but had it revoked when their partner was hospitalised described this as very frustrating.

Since sick pay is not primarily for caregivers, we did not ask participants about this directly. However, several participants had received sick pay. Whether the caregiving role was so demanding that it caused them to become ill themselves or if they simply found the sick pay scheme to be the most accessible option is not clear, and further investigation is needed.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study included participants from the Norwegian Cancer Society’s user panel, representing various parts of Norway. A potential limitation of the study is that our participants may have been more affected by living with someone with cancer compared to other partners, as they had chosen to be members of the Norwegian Cancer Society and its user panel.

It may also be a strength that the participants were likely to have been particularly interested and engaged, resulting in rich and contrasting descriptions. The interviewers’ lack of experience with data collection may have limited the number of follow-up questions, which could have resulted in more in-depth data.

However, the first two authors had been trained in communicating with patients and their families. This may have had a reassuring effect during the interviews, which in turn encouraged the informants to share detailed descriptions of very personal experiences.

We conducted the interviews digitally, via phone or in person. Without these flexible options, the recruitment of participants would have been a challenging process. In remote meetings, it can be difficult to establish a good rapport and it is harder to observe body language. In contrast, the distance may feel comfortable and safe for some participants. Allowing participants to choose the interview format, along with the relatively short duration of the interviews and the absence of travel costs, were all strengths.

A retrospective perspective gives participants time to reflect on their experiences as a caregiver and what information and support they felt was lacking in this situation. One limitation is that the findings may not be completely reliable, as memories and emotions can change over time. The strength of the information was assessed throughout, with all authors involved in developing the themes through shared reflections, known as researcher triangulation.

It is difficult to know whether saturation was achieved. In our study, we only had access to 11 participants, and all were interviewed. It is possible that we would have received different answers and/or drawn different conclusions if more participants had been available. We consider it a limitation that only two men were included in the sample and that most participants had highly flexible jobs.

Conclusion

Cancer affects many people and therefore has an impact on a significant number of family members. We found that while it is crucial for partners to provide care and support to their ill spouse/cohabitant, continuing to work can be a challenge. However, work provided a breathing space and respite from their everyday life at home. Those with less flexible jobs who took sick leave in the early stages of their partner’s illness had more difficulty finding a sanctuary and were under a greater strain.

The experiences of partners of seriously ill cancer patients may also be relevant for family caregivers of individuals with other diseases. Several participants called for user-friendly support services and relevant support schemes for family caregivers. This feedback could be important for employers, clinicians, patient organisations and those responsible for shaping family caregiver policies.

Funding

This study received funding from the DAM Foundation and the Norwegian Cancer Society.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to the participants who shared their experiences with us. This article would not have been possible without you.

Irma Taslidza and Gunhild Eide Myhre share first authorship.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments