Intensive care nurses with a child welfare role – opportunities and differing expectations

Summary

Background: Around 20,000 critically ill patients are treated in intensive care units (ICUs) in Norway every year. Family members include many children and young people in vulnerable situations. Norway’s Specialist Health Service Act relating to Children and Young People as Caregivers was amended in 2010. This led to the specialist health service establishing functions such as personnel with a child welfare role. These healthcare professionals were specifically tasked with supporting patients’ children and serving as a resource for clinical personnel. Our knowledge is limited on how the duties of intensive care nurses with a child welfare role have been carried out. Furthermore, we do not know which challenges are still relevant.

Objective: To investigate the experiences of intensive care nurses with a child welfare role, in relation to their tasks and function following introduction of the requirement for this role in 2010.

Method: Individual qualitative in-depth interviews of 14 nurses conducted between autumn 2019 and spring 2022. We aimed to investigate their experiences with executing tasks in their function as an intensive care nurse with a child welfare role. We analysed the data using an inductive and descriptive approach.

Results: The analysis resulted in two main themes: ‘Statutory requirements meet everyday limitations’ and ‘Need for support within the organisation’. The nurses with a child welfare role reported that the limited resources available to them made it difficult to meet the expectations stemming from the legal requirements.

Conclusion: ICU personnel with a child welfare role in Norway operate within a broad spectrum of challenging tasks and responsibilities in the daily care of critically ill patients. One of their primary objectives was to facilitate an inclusive environment for children and young people, recognise and address their individual needs and support the family. There is still room for improvement in this regard.

Cite the article

Frivold G, Lind R, Moi A. Intensive care nurses with a child welfare role – opportunities and differing expectations. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(95370):e-95370. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.95370en

Introduction

In 2022, intensive care units (ICUs) in Norway recorded 20,021 admissions of 16,590 patients (1). The family members of chronically and critically ill patients include a large number of children and young people, including those with parents, siblings, grandparents and other close relatives who are affected by serious illness or injury (2).

The rights of children and young people who are family members of hospital patients were enshrined in law in 2010 through Section 3-7 (a) of the Specialist Health Services Act and Section 10 (a) of the Health Personnel Act. To implement this legislative amendment and protect children’s rights, requirements were introduced for personnel with a child welfare role in all departments in the specialist health service (4).

Patients’ children are entitled to have the situation explained to them in a way they understand. Personnel with a child welfare role in the specialist health service are responsible for promoting and coordinating healthcare personnel’s follow-up of children in this group.

Earlier research on patients’ children

Admission to an ICU can be dramatic for patients and their family (5, 6), and it often takes place as an emergency, giving them little time to prepare. Patients’ families are exposed to major emotional stress, and the situation can have a negative impact on their lives and health (7–9). In this situation, patients’ children will need reassurance. They need explanations that they can understand and they need to be included (10, 11).

Making these children and young people feel included is also crucial for their ability to understand the adults’ expressions of grief, despair and uncertainty. It can also help reduce the sense of helplessness, guilt, separation and self-blame and give them an opportunity to express their own feelings and needs (12).

A national report from BarnsBeste (13) concluded that the legal provision for personnel with a child welfare role was only partially complied with, and that there should be more systematic efforts to implement the legislative amendment. A follow-up survey revealed that personnel with a child welfare role largely perform tasks that all healthcare personnel should carry out for patients’ children (14). No specific data emerged from departments that treat critically ill somatic patients.

The term ‘family-centred care’ (15) is relatively new within the context of the ICU. Respect, dignity, information sharing, participation and collaboration are core elements of this concept (16).

Because many ICU patients lack decision-making capacity and the ability to communicate their needs, we need to understand family-centred care as more than just the family’s right to visit the patient. Family-centred care is rooted in a comprehensive approach that recognises the experiences of patients as well as their families. It involves facilitating family presence in hospitals, addressing family members’ needs and promoting family engagement (17, 18). A stronger focus needs to be placed on these factors in relation to patients’ children.

According to a study by Knutsson et al. (10), the procedures for involving patients’ children are better in mental health care than in somatic departments. ICUs in Norway have had dedicated positions for nurses with a child welfare role since the legal provision came into effect in 2010. However, little is known about the experiences of intensive care nurses in the child welfare role in Norway.

Objective of the study

To investigate the experiences of intensive care nurses with a child welfare role, in relation to their tasks and function following introduction of the requirement for this role in 2010.

Method

The study has a qualitative descriptive design (19, 20) and explored experiences through individual interviews with intensive care nurses and other nurses – hereafter referred to collectively as intensive care nurses – with a child welfare role in an ICU in Norway. We transcribed the interviews and analysed the data using an inductive and descriptive approach. The personnel’s experiences form the basis for new knowledge on how we can best support children and young people who are family members of ICU patients.

Sample and recruitment

The participants were recruited from nine ICUs in three Norwegian health trusts, where the context of their role varied. Some worked as part of a hospital network, while others had sole responsibility for child welfare or joint responsibility with other ICU personnel. The sample consisted of 13 women and 1 man, with 2–10 years of experience (median 6 years) in the child welfare role.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted between autumn 2019 and spring 2022. All in-person interviews were held in a private setting at the informants’ place of work. The interviews during the pandemic were conducted via a secure digital audio-visual platform.

Seven interviews were conducted by a master’s student and the first author, two by the second author and five by the last author. We made audio recordings of the interviews and took contemporaneous notes. A semi-structured interview guide was used (Appendix 1 – in Norwegian).

The interview guide was further developed by the authors based on the original interview guide from the master’s project. After an initial open-ended question about experiences in the child welfare role, more detailed follow-up questions were asked. The audio files were transcribed, and the transcriptions were anonymised and stored on a research server at the University of Agder. Three interviews were transcribed by a master’s student, four by the first author and the remainder by an approved transcriber.

Analysis

We analysed the data in line with an inductive and descriptive approach and used NVivo software (21) to code the text and identify patterns of meaning in the interviews. The first author led the analytical work. All three authors have extensive experience as intensive care nurses.

Throughout the research process, we sought to reflect on our own point of view and keep an open mind about the participants’ experiences. We worked on our own to start with and then together. The themes were developed in six phases in line with Braun and Clarke’s recommendations (19, 20).

In the first phase, we familiarised ourselves with the material by identifying aspects that were immediately recognisable. We then reflected on the material while maintaining a critical distance, and engaged in analytical inquiry. The first author then coded the data across all interviews.

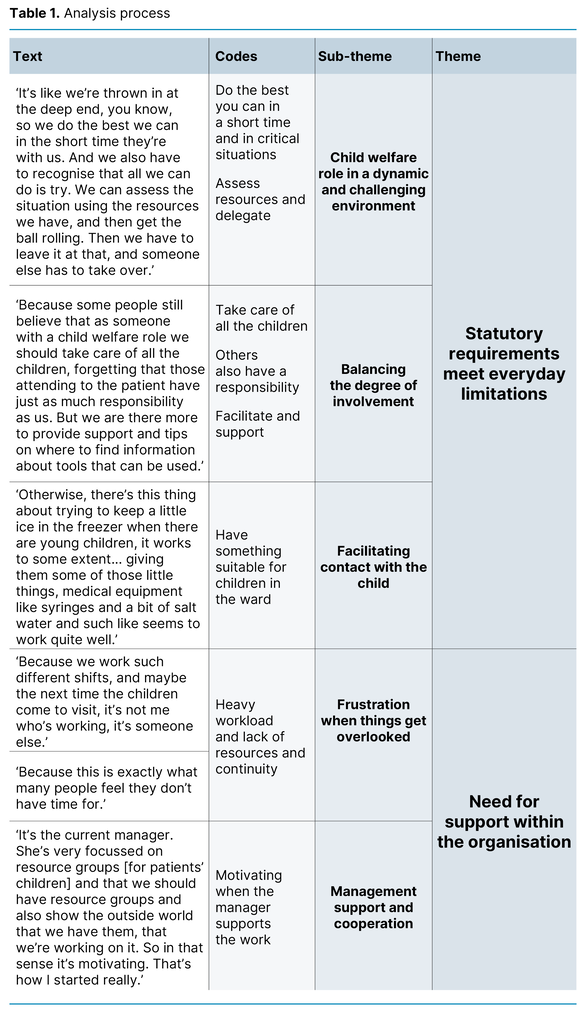

We discussed and developed the initial codes and then generated preliminary themes. We iterated the analysis process between codes and themes until the final themes were defined and named. The analysis process is shown in Table 1.

Ethical considerations

The study has been assessed by Sikt (the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research) (reference number 210608) (22) and the Ethics Committee at the University of Agder (reference number 21/00608). In accordance with data protection regulations on liability in relation to collecting, processing and storing data, a data processing agreement was established between the institutions responsible for the research: the University of Agder, UiT The Arctic University of Norway and the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (Appendix 2 – in Norwegian).

Written informed consent was obtained from the informants for participation in the study. They received written and oral information about the purpose of the study, their rights and practical details.

Results

The child welfare role was in addition to the other tasks that all intensive care nurses carry out. Categories of job instructions and full-time equivalent percentages associated with the child welfare role varied. The study shows that some of those with a child welfare role carried out this role alone in their unit, while others were part of a resource team. The dual role of the former meant they faced extra challenges; they had to manage the daily patient care, which was challenging enough in itself, alongside the child welfare role.

The analysis resulted in two main themes: ‘Statutory requirements meet everyday limitations’ and ‘Need for support within the organisation’. as well as five sub-themes: ‘Child welfare role in a dynamic and challenging environment’, ‘Balancing the degree of involvement’, ‘Facilitating contact with the child’, ‘Frustration when things get overlooked’ and ‘Management support and cooperation’.

Statutory requirements meet everyday limitations

The informants found being an intensive care nurse with a child welfare role rewarding, exciting and challenging. A common feature is that all informants identified good opportunities to shape their own role within given frameworks and conditions.

Child welfare role in a dynamic and challenging environment

Everyday life was characterised by unforeseen situations where there was little room for planning, both in short- and long-term hospital stays:

‘It’s like we’re thrown in at the deep end, you know, so we do the best we can in the short time they’re with us. And we also have to recognise that all we can do is try. We can assess the situation using the resources we have, and then get the ball rolling. Then we have to leave it at that, and someone else has to take over.’

The context here also includes life-critical situations, where intensive care staff have to make snap decisions and undertake actions in collaboration with patients and their families. It was precisely in these situations that those with a child welfare role described having particular challenges, as patients’ children had to be deprioritised.

Balancing the degree of involvement

The child welfare role primarily involved having overall responsibility for supporting patients’ children. Tasks also included sharing factual knowledge about the children’s situation and needs with staff and students. However, several personnel with a child welfare role experienced a cross-pressure, as one informant somewhat irritably expressed:

‘Because some people still believe that as someone with a child welfare role we should take care of all the children, forgetting that those attending to the patient have just as much responsibility as us. But we are there more to provide support and tips on where to find information about tools that can be used.’

Managing colleagues’ expectations of them to get involved in individual situations could be challenging. Nevertheless, they were a valuable resource for colleagues and parents, for example by informing the public health nurse or teacher about the child’s special situation with a close relative in an ICU.

Consequently, the child could receive help in maintaining as normal a daily life as possible. The study informants emphasised that it was easier for them to understand the overall picture of a family member’s situation and contact the child’s network when they did not have responsibility for the patient.

The informants found that the greatest practical change following the legislative amendment in 2010 was the requirement for patient medical records for all admissions to indicate whether the patient had dependent children. As an extension of this measure, an assessment was also to be made of the child and family’s circumstances, along with their need for follow-up. The informants identified this change as the easiest to measure.

Nevertheless, the documenting of the necessary information and the assessment could be challenging. The personnel with a child welfare role worked to ensure that nurses provided more details in the patient medical records than the minimum requirement. It was normally noted when the patient had dependent children, but this could be overlooked during short hospital stays.

The informants reported that they were more uncertain about the detailed recording of information in the patient medical records about patients’ children:

‘Then it’s like, we’re going to report this to the child welfare service. That’s what people wonder about the most. So everyone has a clear opinion on whether this should be reported, but we’re unsure. How was it again, and where was the DIPS form, and who was I supposed to send it to, then I have to phone in advance. I guess that’s what there are so many questions about.’

They were uncertain about whom to report to in situations where a need for follow-up was identified. They were also unsure if such reporting was within their remit, and if not, would someone else address the issue?

Facilitating contact with the child

An important part of their remit was to impart knowledge and facilitate a child-friendly ward. Designated ‘children’s corners’ with toys, books and age-appropriate worksheets and information material was just one of the measures implemented to show that children were welcome in the ICU. The informants found that young people need different measures from younger children:

‘Young people and older children all have mobile phones nowadays. They often bring tablets and such like, so we arrange free Wi-Fi access for them in the hospital, so yeah, these little things, we have at least that.’

In the interviews, nurses with a child welfare role expressed that they understood the importance of recognising the individual needs of each child and addressing them according to their particular capabilities:

‘We really feel for these children and think it’s crucial that they receive information tailored to their level.’

Several nurses with a child welfare role had experienced children being shielded by the adults in the family by not being allowed to visit the patient. They therefore considered guiding the family to facilitate children’s participation on their own terms to be an important task. The adults taking care of the children were regarded as the most important partners in the work with patients’ children. By supporting the adults, the personnel with a child welfare role felt that they were also supporting the children.

Need for support within the organisation

The opportunities and challenges of the child welfare role were considered in relation to the organisational conditions in the hospital departments.

Frustration when things get overlooked

The informants faced challenges in the child welfare role, both at a personal and system level. Working shifts with an uneven workload and little continuity in patient care makes it difficult to follow up patients’ children. The short-term nature of some hospital stays meant that the registration of patients’ children could be overlooked. On busy days with understaffing and critically ill patients, it could be difficult for the intensive care nurses to attend to patient’s families, and their children in particular:

‘I find it frustrating when we want to do so much, and when you get started with things and try to get a bit of continuity, it doesn’t work out. I understand that the patient comes first, but other factors are also an important part of the job.’

Some departments had established specialist teams of personnel with a child welfare role. This was particularly important when there were challenges with certain family members, and it enabled intensive care nurses to seek advice from others and discuss experiences from similar situations. The informants also described how they were inspired by the established resource groups that had national cooperation for personnel with a child welfare role. These large forums could particularly be helpful for shedding light on challenges, for example in the case of reported wrongdoing. Such cases could make the child welfare role challenging and had led to uncertainty among the staff.

Management support and cooperation

Management engagement was highlighted as essential for maintaining the motivation of those with a child welfare role. When a manager had identified a need to facilitate sufficient time and resources, the personnel with a child welfare role felt supported in their efforts to effect useful measures. Working with others in an extended team inspired their work with patients’ children:

‘But if you work as part of an interdisciplinary team, when the doctor also takes an interest, in addition to nurses and physiotherapists, for example. Because if we’re all focused on what we have to do, it’s much easier. Because we have to work as a team. Yes, because it’s a tough department we work in. But we have to create a space for children to come and feel safe. Guide parents, because they often just need a few tips.’

Networking and collaboration across departments and hospitals strengthened the professional standard of the services. These hubs, where knowledge and experiences were shared, were described as crucial for informants being able to sustain their role over time. They highlighted networking and interdisciplinary collaboration as important elements of the basis for good solutions in the practical daily work in ICUs.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to investigate the experiences of intensive care nurses with a child welfare role, in relation to their tasks and function following introduction of the requirement for this role in 2010.

Statutory requirements meet everyday limitations

The findings of the study show that personnel with a child welfare role considered the function and tasks rewarding, exciting and challenging, but that this was dependent on the prevailing frameworks and conditions.

The term ‘family-centred care’ (16, 23, 24) appeared to be well established, albeit primarily in relation to paediatric patients as opposed to patient’s children. The needs of patients’ adult family members are often related to involvement in decision-making (15, 25), whereas children primarily need to understand, and to be acknowledged and included (11, 26).

A systematic review (27) shows that being present in the ICU has a positive effect on children and young people. It provides them with the necessary understanding, but they need tailored information. The findings in our study highlight the importance and challenging nature of addressing children’s needs on their terms in the context of intensive care. There is still room for improvement in this area.

The intention behind implementing practical measures for ICU patients’ children was to recognise their needs in an alien hospital setting with all sorts of wires and machines. It is therefore important that children have the opportunity to be present and receive tailored information (28, 29).

As a follow-up to the practical measures, the personnel with a child welfare role had developed various strategies for age-appropriate information and learning, often through readily accessible written materials in the wards. However, it appears to be much more common to provide support to parents than to help patients’ children directly. There is still a need to recognise the best strategies for addressing children’s needs on their own terms, even while also supporting the parents.

Children of cancer patients (30) and mental health patients (31) are often in this situation for a long period of time. Children of ICU patients are usually ‘thrown’ into a new situation and are completely unfamiliar with what being the child of a patient entails. This presents specific challenges for personnel with a child welfare role. In cancer care, there is a long history of organisations providing national support schemes (30). In the field of intensive care, there are no such dedicated forums to which children can be referred.

Need for support within the organisation

The study shows that expertise on being a child of a patient is achieved by establishing a systematic framework within organisations. Training and professional follow-up in the department are also needed. A review of Norwegian literature on healthcare personnel’s child welfare role (32) points out that this function must be anchored in management.

A recently published scoping review examining nurses’ leadership in the intensive care unit (33) concluded that communication skills, emotional intelligence and innovation development are particularly important. According to Schaufeli, engaging leadership that facilitates, strengthens, connects and inspires employees is key to promoting work engagement (34).

A new Norwegian survey of 1600 nurses (35) showed that intensive care nurses have largely been trained in the legislation and tasks relating to the child welfare role vis-à-vis patients’ children. After nurses specialising in substance use and mental health, intensive care nurses are the next likely to report having this child welfare role.

Our study shows that the knowledge base in the nursing profession regarding legislation and national recommendations is well established. However, the informants felt that they needed more time to carry out their tasks and more continuity. When this was lacking, the standard of the work deteriorated, and they felt less capable in the child welfare role. The study found that effective procedures are in place, but that compliance with these is still lacking in relation to following up patients’ children. This applies to record keeping and the implementation of practical measures (35).

Findings from our study show areas where personnel with a child welfare role want to see improvement, such as more knowledge through training courses and practical training, sufficient time to fulfil their child welfare role and targeted managerial support. The survey by Thorsen et al. also recommends improvements in these areas (14).

Strengths and limitations of the study

To our knowledge, this study is the first to shed light on the topic of the child welfare role in an intensive care perspective. The study includes participants from several ICUs in different Norwegian health regions, thereby strengthening transferability to other ICUs. The data were collected over an extended period of time. It should also be noted that conditions changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced the findings of the study.

Conclusion

Personnel with a child welfare role in Norwegian ICUs navigate a broad spectrum of challenging tasks and responsibilities in the day-to-day care of critically ill patients.

The primary objectives of the intensive care nurses with a child welfare role who participated in this study were to facilitate an inclusive environment for children and young people, recognise and address their individual needs and support the family. There are still opportunities for improvement here.

These nurses experienced differing expectations stemming from legal requirements that needed to be met, whilst also facing constrained organisational frameworks and resources to implement the measures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Susanne Rønquist Knutsen, who conducted three of the interviews, and all the informants who shared their valuable experiences about their child welfare role.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments