Parents’ experiences of having an adult daughter with an eating disorder

They are ever on the alert vis-à-vis their daughter, suffer loneliness and feel that the eating disorder is taking over their home.

Background: Having a family member who suffers from a severe eating disorder can have a significant impact on family life. Earlier research shows that parents feel anxious and worried and that they carry a heavier burden of care and strain. Compared to the parents of individuals with other severe mental disorders, this group carries a heavier burden of care. They express a greater need for information and assistance from the health services. There is evidence of a correlation between the duration of the disease and the parents’ experiences.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to describe the experiences of parents who have an adult daughter with a severe eating disorder. Knowledge about parents’ experiences may help to improve the range of support offered to families.

Method: The parents’ experiences were collected by conducting qualitative in-depth interviews with open-ended questions. The chosen analytical method was Graneheim and Lundman’s content analysis. The group of participants consisted of five mothers and six fathers of adult daughters (21–23 years) who suffered from either anorexia or bulimia.

Results: Three categories were identified: ‘ever on the alert’, ‘the eating disorder takes over the home’, and ‘loneliness’.

Conclusion: The findings show that the daughters’ severe eating disorders impacted on the parents’ lives in the form of stress, anxiety, shame, powerlessness, reduced health and loneliness. The health service referred to the need to maintain patient confidentiality and that they carried the primary responsibility for the patient. Based on these findings it emerged that the parents were ‘ever on the alert’. Their situation also meant reduced contact with family and friends. The parents felt left to their own devices with a responsibility that was overwhelming. It is important for healthcare personnel to be familiar with the experiences of parents as this will enable conversations with them about the eating disorder and their caring role. Such knowledge can also be used to develop services that better meet the needs of parents of adult patients.

Having a family member with a severe eating disorder can have an impact on all aspects of family life. In this study, eleven parents of adult women with anorexia or bulimia were interviewed about their experiences as carers.

Mothers and fathers describe their experiences of living with a family member who suffers from an eating disorder and their encounters with the health services. The responsibilities that many relatives take on for their loved ones, and the care they provide, make up a key part of society’s total care resources (1).

It is important that registered nurses and other healthcare personnel are familiar with the experiences of parents to enable conversations with them about relevant themes in relation to the eating disorder and the role of carer.

Government recommendations, guidelines and evidence-based practice attach importance to experiential competence as well as to collated reflections on the experiences of service users and their next of kin. The experiences of parents can be useful as we seek to further develop and improve services.

Eating disorders in Norway

There are no accurate or up-to-date figures for the incidence of eating disorders in Norway. In 2015, the specialist health service treated 5500 patients for an eating disorder (2). Of these, 43 per cent were registered with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, and 25 per cent with a diagnosis of bulimia (2).

An eating disorder is defined as an obsession with food, body shape and weight to the extent that it affects a person’s normal activities, reducing their quality of life (3). Anorexia nervosa is considered to be the most deadly diagnosis of all mental health disorders (4).

Anorexia manifests as severe underweight and a fear of putting on weight. People who suffer from anorexia often perceive their body to be large, despite being underweight. Bulimia manifests as repeated episodes of over-eating followed by vomiting. People who suffer from bulimia often maintain a normal weight (3).

The experiences of family members

Weimand (5) analyses the experiences of family members of people with severe mental illness and highlights their need for assistance from the health services. Providing care and support for one’s loved ones can be a meaningful preoccupation which gives a sense of mastery.

Family caregivers can also encounter challenges and dilemmas. They may experience isolation, stress, strain and exhaustion (1). Baronet’s (6) critical review shows that mental illness in one family member means that other family members are under increased strain and take on additional caring chores.

Earlier studies of family caregivers

Several studies have compared carers for family members with eating disorders to carers of family members affected by other severe disorders, such as substance abuse, depression and schizophrenia. Linacre and Hills (7) found that carers in the former group have a poorer quality of life than those who care for family members with psychotic problems.

Several of these family caregivers suffer from reduced mental health, stress and a curtailed social life. There is often a correlation between the caregivers’ mental wellbeing and the duration, severity and outcome of the disease.

People who look after family members with an eating disorder feel that they carry a heavier burden of care than people who look after family members with psychotic disorders (7). They express a need for assistance and information from the health services and seek greater involvement with the patient’s treatment (8–13).

Family caregivers often struggle with anxiety and depression if they live with someone who suffers from an eating disorder (6). Some studies show a high incidence of depression, particularly among mothers, caused by the family situation (14–16). Mothers, unlike fathers, feel a heavier burden of care (17).

Some of the literature has focused on minors with eating disorders and their caregivers’ need for help and support (18–22). The parents of children with anorexia can speak of a hope of recovery, and their quality of life is not yet as heavily affected (20, 22).

Eisler (23) writes that many individuals who suffer from an eating disorder tend to continue living with their primary relatives for longer than their peers. Compared to others, the families are involved with the lives of their children to a greater extent than what is natural for their biological age.

A systematic review shows that there is a correlation between the duration of eating disorders and the experiences of family caregivers (8). It emerged from one qualitative study on long-term eating disorders that families gave varying degrees of support to relatives affected by an eating disorder (24).

Few studies have focused on adults with long-term eating disorders (7). Our own systematic literature review found no other research on the parents of adults with anorexia or bulimia.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study is to describe how it feels to be the parent of an adult daughter with a severe eating disorder. Knowledge about the experiences of parents may help to improve the range of support offered to families.

Method

Research design

The design of the study is qualitative and exploratory. Data were collected by conducting in-depth individual interviews with the parents of young adult women with severe eating disorders. Our chosen analytical method is Graneheim and Lundman’s qualitative content analysis (25).

The project was managed by the last author. The study was conducted by all the authors while two fellow researchers with lived experience as patient and parent took part in the discussion of our findings.

Recruitment and research ethics

The parents were recruited via a unit for eating disorders at a Norwegian hospital. They had previously taken part in multifamily therapy (MFT) (26, 27) and were invited by the last author to participate in the research project. The number of participants was determined on the basis of saturation.

Out of fourteen invited parents, eleven consented to taking part. No further study participants were included because new information was no longer forthcoming from the interviews.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research project was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) on 13 July 2017 (reference number 2014/1621/REK vest).

All participants received verbal and written information about the project and signed a form of consent. They were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The data material was anonymised and treated confidentially.

Participants

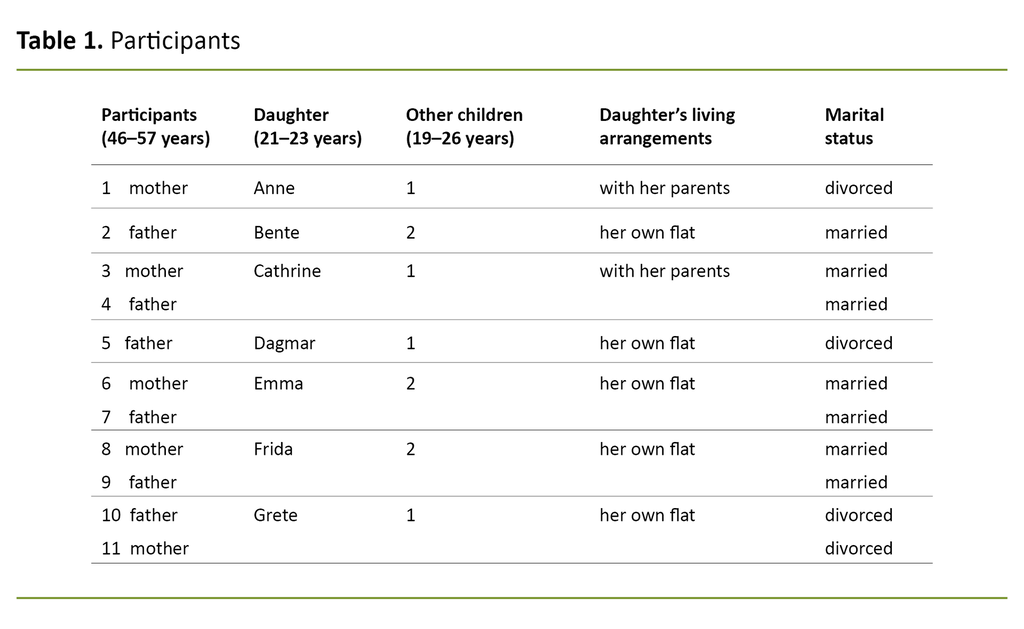

The group of participants consisted of five mothers and six fathers of seven young women with severe eating disorders (Table 1).

Five of the young women had been diagnosed with anorexia as their main disorder. Some had also experienced vomiting and problems with excessive exercise, and some suffered from comorbidities such as self-harm and personality disorders. Two of the women suffered from bulimia.

All the women had been affected by the disorder for a long time, from two to seven years, and had been hospitalised on several occasions. Most of them had been sectioned. None of them were in hospital at the time of the interview with their parents. One of the parents and one of the siblings also suffered from an eating disorder.

Conducting the interviews

The interviews were conducted in the period between 31 August and 19 October 2017. We interviewed each parent separately. The participants chose whether they preferred to be interviewed in an office at the hospital or in their own home. The first, second and last authors conducted the interviews. The last author attended all the interviews.

For training purposes, the first and second authors accompanied the last author during six of the interviews. The third author had previously encountered some of the patients in her clinical practice and did not take part in the data collection process. We used qualitative in-depth interviews with open-ended questions.

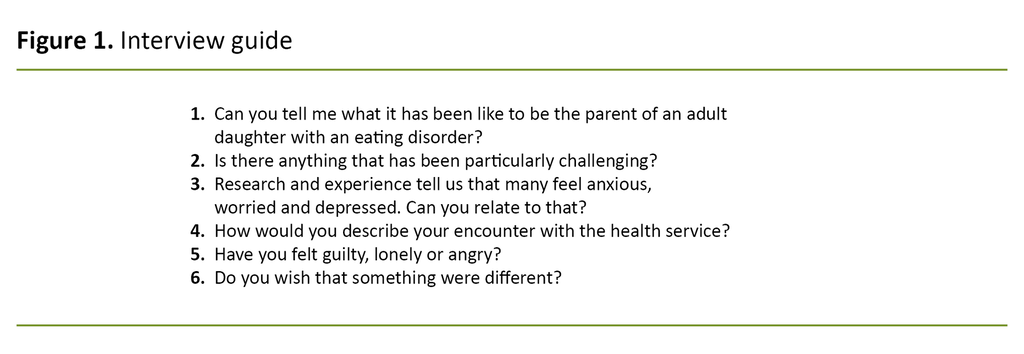

The participants were asked this introductory question: ‘Can you tell me what it has been like to be the parent of an adult daughter with an eating disorder?’ This was supplemented with additional questions (interview guide, Figure 1). We designed the interview guide based on experience from our practice and earlier research.

We did not follow the interview guide rigorously. We found that the participants talked freely about their experiences, including positive ones. Each interview lasted 60 - 90 minutes and they were all recorded on tape. The data material was transcribed verbatim. The combined word count for all the interviews was 81 258.

Analysis

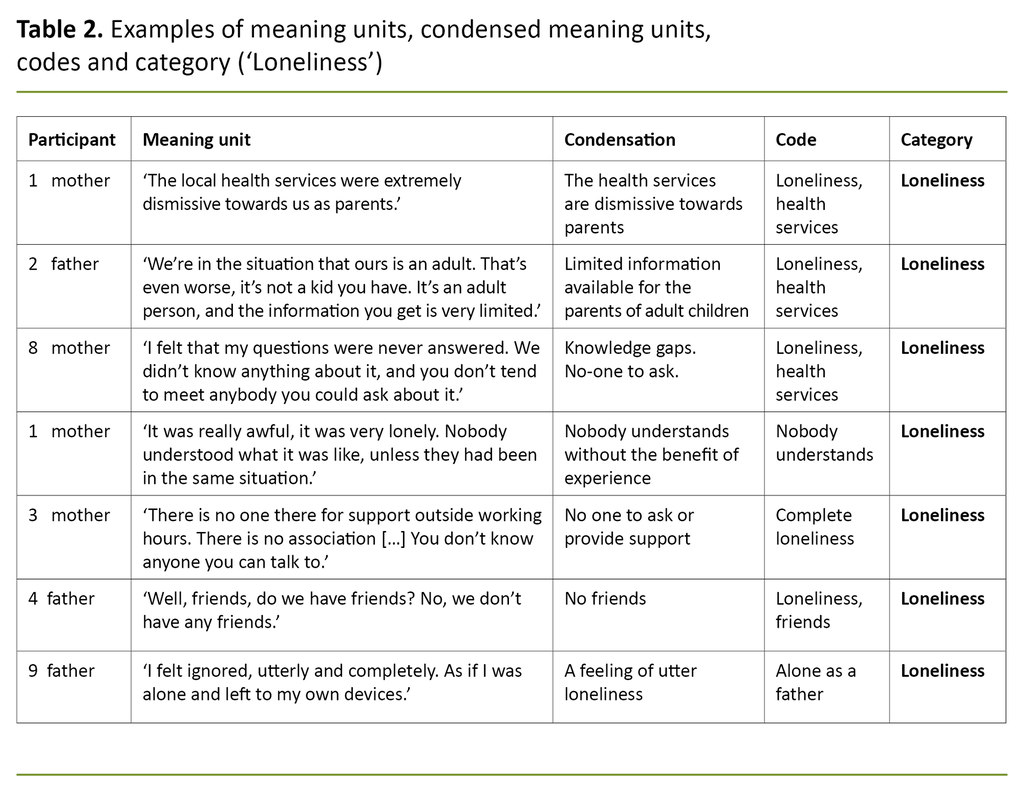

Our chosen analytical method was Graneheim and Lundman’s (25) qualitative content analysis. We started by reading through all the interviews so we could form an overall impression of their content. Meaning units such as word, sentences and paragraphs were then identified and condensed into truncated segments of text.

The condensed meaning units were labelled with codes and categories were formed by merging codes that were found to denote similar content (25) (Table 2).

All the authors contributed to the analysis. The first interview was analysed by all the authors in concert. We then distributed the remaining ten interviews between us and worked to identify meaning units, condense the text, label with codes and establish categories – individually at first, then in pairs.

Throughout this phase, we circulated between partners to ensure that each individual had worked with all the other authors at one stage in the process. Finally, all the authors met up to discuss preliminary sub-categories and suggestions for main categories. These categories were also presented to and discussed with two fellow researchers with lived experience as patient and parent.

Results

The interview findings can be summarised in three categories: ‘ever on the alert’, ‘the eating disorder takes over the home’, and ‘loneliness’.

Ever on the alert

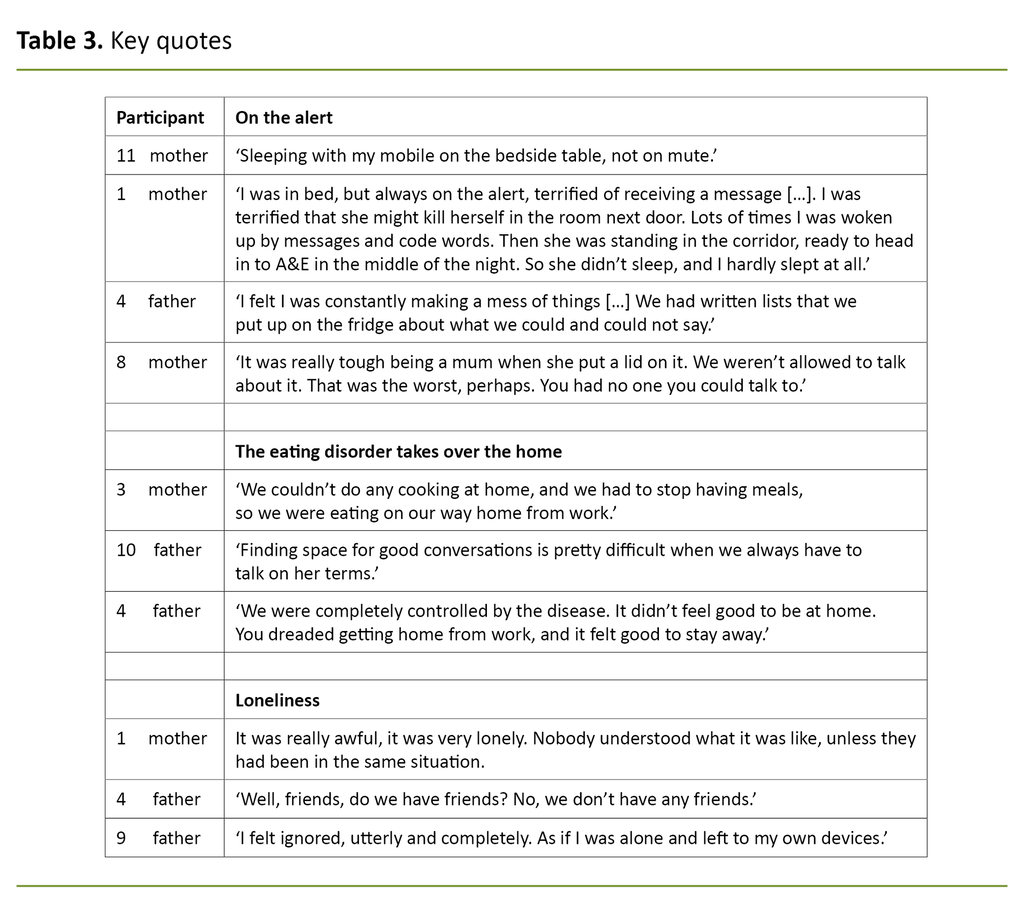

The main finding of our study describes a feeling reported by all the parents interviewed, that they were ‘ever on the alert’ vis-a-vis their ill daughter, vis-a-vis the other parent, other family members, friends and even the health services.

Several parents explained that they were constantly on maximum alert because they kept telling themselves that something serious might happen. One father described how he bedded down outside his daughter’s bedroom every night to keep watch over her. In another family, a mother was lying awake all night with her mobile phone at the ready on her bedside table, in case her daughter sent her a message.

Several parents explained that they were constantly on maximum alert.

Some described a balancing act in the way they related to their daughter. The parents felt powerless faced with their daughter’s distress and felt they had to avoid everything that might give rise to conflict. In some homes, rules had been introduced that governed what could and could not be said.

Misinterpretations could trigger terrible outbursts of anger. Visits from friends and acquaintances could end up in confrontations because something had been said the wrong way or was misinterpreted by the daughter. Several parents explained that they felt they had to conform with the rules for acceptable subjects of conversation, and that their room for manoeuvre vis-à-vis the health services was also restricted.

Some feared that the health services would counter them with the need to maintain patient confidentiality, and some avoided contacting the health services because their ill daughter did not want this type of involvement from her parents (Table 3).

The eating disorder takes over the home

The parents felt that the eating disorder took increasing control over their daughter’s life, and that it eventually took over their home and controlled the lives of all the family. Food became a taboo at home. Some parent stopped cooking completely to avoid a smell of food in the house.

Seasonal celebrations and gatherings with family and friends could become onerous. Some felt this was too challenging; they stopped attending family gatherings and other social settings that involved food in order to protect themselves and their daughter.

The parents felt it was difficult to see their daughter becoming ever thinner and being unable to talk about it. The disorder came to control the subjects of family conversations (Table 3).

Loneliness

The participants talked of loneliness vis-à-vis their partner and other family members because the eating disorder put a wedge between the parents and led to conflicts between them, as well as between the daughter and the parents. Many parents talked about having lost contact with friends and family due to the daughter’s disorder.

Friends and family did not understand how difficult things were, and the family situation was so dominated by the eating disorder that it was difficult to welcome visitors. The participants felt extremely lonely in their role as parents. When they contacted healthcare personnel for support, advice or information, they were met with the need to maintain patient confidentiality. The information they received was dictated by whatever their daughter wanted them to hear.

According to the participants, they found themselves in a situation so challenging that they wondered whether life was worth living.

Parents and guardians worry about their children beyond the age of 18. The parents we interviewed did not always know if their daughter was in hospital and whether or not things were going well. When a family member suffers from a severe disorder, the feeling of loneliness is exacerbated if any enquiry directed at the health service is countered with the need to maintain patient confidentiality.

According to the participants, they found themselves in a situation so challenging that they wondered whether life was worth living. The life they used to live had gone, and they feared that they would never get it back. They wanted to escape from the situation they were in (Table 3).

Discussion

The parents felt that they were left to their own devices, their own knowledge gaps and all the challenges that the eating disorder brought with it. They felt that there was no one to turn to for support.

According to Highet et al. (28), the feeling of loneliness and inadequate help and support is exacerbated by the fact that there is little awareness and understanding of eating disorders in society at large. Their study was conducted in Australia, where healthcare provision is described as insufficient or difficult to access.

The majority of the studies covered by Fowler’s (9) review article were conducted in Australia and England. The reports are of long waiting periods, which can adversely affect the condition. Another Australian study shows that the focus is solely on the person with the disorder, despite the fact that eating disorders affect the whole family (29).

Families in Mediterranean countries may have a higher tolerance level for looking after sick relatives, because family members tend to live together for longer (8). Culture affects not only one’s perspective on eating disorders, but also how the health services work (30).

Parents feel excluded by the need to maintain patient confidentiality

Despite having the Norwegian welfare system as their term of reference, the parents in our sample also talked of insufficient assistance from the health services, and they felt the need to maintain patient confidentiality to be an encumbrance. It is difficult to compare these findings across cultures, as parents’ expectations of the health services may well differ.

They felt the need to maintain patient confidentiality to be an encumbrance.

In welfare states such as Norway, relatives expect to receive a certain amount of help and they are concerned about the quality of the assistance on offer. It is a recurring theme that parents feel excluded by the need to maintain patient confidentiality, and that they have relatively little involvement with the treatment. The theme in many of the international studies is that no help is forthcoming.

Dialogue became a difficult balancing act

According to Weimand (5), individuals who care for family members with a mental illness tend to feel that their relationship with that person is highly fragile. The parents in our sample describe that relating to their daughter feels like walking a tightrope. Attempts at dialogue with their daughter could be met with anger, aggression, self-harm and rejection.

They also felt it was difficult to set boundaries for unacceptable behaviours. Adjustments were made at multiple levels to meet the needs of the family member with the disorder. For example, it was considered challenging to welcome visits by family and friends. The daughter controlled the family’s social network. According to Eisler (23), relatives often find themselves trapped in the situation.

They may know that what they are doing is wrong but fear that any change may aggravate the pain. It is difficult to find a way out of the situation because the daughter depends on continuous help and support. She is an adult, but needs the care of a child (15).

The families felt stigmatised

Highet et al. (28) found that family members often tried to find the right balance between communicating a message and avoiding confrontation and triggering pain. Parents avoided inviting friends and family to their home. Some also found that their network did not wish to visit. The families felt stigmatised (28).

Parents avoided inviting friends and family to their home.

Our material gave no direct indication of stigma, only a slight suggestion that there may be shades of stigma present. It is an expectation in society that adult children should be able to look after themselves. Outsiders may find it difficult to understand the burden of care that these parents are carrying.

It becomes even more of a challenge if the person with the disorder is living in the family home. These homes become isolated units where no one else is allowed access. The families are left to their own devices with the responsibility of caring for the person with the disorder (28).

The parents complied with the daughters’ demands

In order to avoid an aggravation of the eating disorder, the parents in our sample complied with many of their daughter’s demands. The parents made adjustments for the benefit of the person with the disorder. Elements of protection and over-protection can be prominent in such relationships, which may lead to parents feeling that they are losing control, while those who are ill find themselves exerting increasing control (31).

Fox et al. (10) found that parents went far to meet the needs of the person with the disorder. This involved re-organising their daily lives, sacrificing their own activities and taking time off work. Much time was spent on preparing and monitoring meals.

Our participants used words such as frightening and depressing to describe this change in the family dynamics. One mother in our material explained that the family stopped cooking at home in order to avoid confrontations. Food is central to every home and is important for social unity, enjoyment and celebration.

In families with an eating disorder it is food and meals that are the source of insecurity, confrontation and isolation. The person with the disorder feels a need to control food, but this leads to loneliness and a loss of control among the parents.

These factors may help to explain why family caregivers for this group of patients describe a heavier burden of care than those who look after relatives with other severe mental disorders (6, 7).

Parents were anxious not to aggravate the illness

Several participants reported that they were worried that their daughter’s disorder might become even more severe and that she would die. Many relatives report that the situation is even more difficult if the disease is long term and there are no signs of improvement and insufficient support available (8–10, 28).

Kyriacou et al. (14) found that particularly mothers of children with anorexia need psychosocial support, and that their own mental health is vulnerable. Our material gave no indication of any significant differences between the experiences of mothers and fathers.

The fact that mothers and fathers share similar experiences may also be culturally conditioned because parents in present-day Norway are considered equal caregivers. In some other countries, gender roles are played out along the lines of a more traditional pattern in that this responsibility falls to the mother.

The strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study is based on a small sample of eleven participants, and it may well be that different nuances would have emerged had we interviewed a large sample. One of the authors has clinical experience of working with the group of patients in question, and her preconceptions may therefore have impacted on the study.

The study was conducted by four authors, which means that it has benefited from a variety of perspectives based on different backgrounds. Two fellow researchers with lived experience as patient and parent have also contributed to our discussion of the results, which strengthens the study’s credibility and validity.

The study’s reliability has been secured in that we have followed and carefully described the steps of out analytic process. Each of the interviews were analysed by two authors working in pairs, and all the authors discussed sub-categories and main categories in concert.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate parents’ experiences of having an adult daughter with a severe eating disorder. It was a common experience among the parents to be ‘ever on the alert’.

Their lives were largely focused on making adjustments to their daughter’s disorder. The feelings of ‘loneliness’ and that ‘the eating disorder took over the home’ can be seen as consequences of these adjustments.

Strain, anxiety, powerlessness and loneliness were key elements. The parents found themselves isolated in their own home, without any ‘interference’ from the health services. Within the home, the daughter with the eating disorder was in control.

Communication within the family, cooking and meals, contact with social networks and information obtained from the health services were adjusted to the daughter’s disorder. The parents felt that they were losing control and that they were left to their own devices with a responsibility they found overwhelming.

The study shows that the parents felt there was insufficient help and assistance forthcoming from the health services. The parents sought information for their own benefit and for the sake of their daughter, but felt that they were excluded despite the fact that user involvement and the family perspective are statutory requirements.

Implications for practice and further research

Nurses need to be familiar with common parental challenges and needs in order to share these experiences with other parents. Such information may help parents understand, find meaning in and handle the demanding situation they find themselves in.

Knowledge about parents’ experiences and requirements may also be useful in the development of health services that better meet the needs of adults. There is a need for studies that focus on the implementation and impact of parental involvement with the treatment of adults, as well as on parental satisfaction with this involvement.

Furthermore, it may be worthwhile to investigate whether the experiences of parents differ depending on whether their sick offspring is a child, an adolescent or an adult, if the experiences of parents vary with different diagnoses such as anorexia and bulimia, and if the experiences of mothers differ from those of fathers.

We are grateful to our fellow researchers Mari Wattum and Ragni Adelsten Stokland for their useful input to this article.

Anne-Lise Grønningsæter Loftfjell and Solveig Margaret Thomassen share the first authorship.

Referanser

1. Helsedirektoratet. Pårørendeveileder. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2017. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/parorendeveileder/om-veilederen (downloaded 23.03.2020).

2. Skarbø T, Rohde M. Norsk kvalitetsregister for behandling av spiseforstyrrelser (NorSpis). Årsrapport for 2016 med plan for forbedringstiltak. Bodø: Nordlandssykehuset; 2017. Available at: https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/sites/default/files/50_arsrapport_2016_norspis.pdf (downloaded 30.04.2020).

3. Skårderud F, Stänicke E, Haugsgjerd S, Maizels D, Engell S. Psykiatriboken: sinn – kropp – samfunn. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2010.

4. Seierstad A, Langengen IW, Nylund HK, Reinar LM, Jamtvedt G. Forebygging og behandling av spiseforstyrrelser. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten; 2004.

5. Weimand BM. Experiences and nursing support of relatives of persons with severe mental illness. (Doktoravhandling.) Karlstad: Karlstad University, Faculty of social and life science; 2012.

6. Baronet A-M. Factors associated with caregiver burden in mental illness: a critical review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19(7):819–41.

7. Linacre SJ, Hill A. The wellbeing of carers of people with severe and enduring eating disorders (SEED). Leeds: University of Leeds; 2011.

8. Anastasiadou D, Medina-Pradas C, Sepulveda AR, Treasure J. A systematic review of family caregiving in eating disorders. Eating Behaviors. 2014;15(3):464–77.

9. Fowler E, Quayle E, Newman E. Supporting someone with an eating disorder: a systematic review of caregiver experiences of eating disorder treatment and a qualitative exploration of burnout management within eating disorder services. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh; 2016.

10. Fox JR, Dean M, Whittlesea A. The experience of caring for or living with an individual with an eating disorder: a meta‐synthesis of qualitative studies. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2017;24(1):103–25.

11. Hibbs R, Rhind C, Leppanen J, Treasure J. Interventions for caregivers of someone with an eating disorder: a meta‐analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2015;48(4):349–61.

12. Sharkey D-AM. Caring for someone with an eating disorder: the experiences and perceptions of carers. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 2007.

13. Zabala MJ, Macdonald P, Treasure J. Appraisal of caregiving burden, expressed emotion and psychological distress in families of people with eating disorders: a systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review. 2009;17(5):338–49.

14. Kyriacou O, Treasure J, Schmidt U. Understanding how parents cope with living with someone with anorexia nervosa: modelling the factors that are associated with carer distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(3):233–42.

15. Hazell P, Woolrich R, Horsch A. Posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of individuals with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice. 2014;2(1):31–41.

16. Ma JLC. An exploratory study of the impact of an adolescent's eating disorder on Chinese parents' well-being, marital life and perceived family functioning in Shenzhen, China: implications for social work practice. Child and Family Social Work. 2011;16(1):33–42.

17. Masa'Deh R. Perceived stress in family caregivers of individuals with mental illness. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2017;55(6):30.

18. Bezance J, Holliday J. Mothers’ experiences of home treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eating Disorders. 2014;22(5):1–19.

19. Franta C, Philipp J, Waldherr K, Truttmann S, Merl E, Schöfbeck G, et al. Supporting carers of children and adolescents with eating disorders in Austria (SUCCEAT): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. European Eating Disorders Review. 2018;26(5):447–61.

20. McCormack C, McCann E. Caring for an adolescent with anorexia nervosa: parent’s views and experiences. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2015;29(3):143–7.

21. Parks M, Anastasiadou D, Sánchez JC, Graell M, Sepulveda AR. Experience of caregiving and coping strategies in caregivers of adolescents with an eating disorder: a comparative study. Psychiatry Research. 2018;260:241–7.

22. Svensson E, Nilsson K, Levi R, Suarez NC. Parents’ experiences of having and caring for a child with an eating disorder. Eating Disorders. 2013;21(5):395–407.

23. Eisler I. The empirical and theoretical base of family therapy and multiple family day therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Journal of Family Therapy. 2005;27(2):104–31.

24. Robinson PH, Kukucska R, Guidetti G, Leavey G. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SEED-AN): a qualitative study of patients with 20+ years of anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review. 2015;23(4):318–26.

25. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24(2):105–12.

26. Brinchmann BS, Moe C, Valvik ME, Balmbra S, Lyngmo S, Skarbø T. An Aristotelian view of therapists' practice in multifamily therapy for young adults with severe eating disorders. Nursing Ethics. 2019; 26(4):1149–59.

27. Skarbø T, Balmbra, S. Establishment of a multifamily therapy (MFT) service for young adults with a severe eating disorder – experience from 11 MFT groups, and from designing and implementing the method. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;8(9):2–12.

28. Highet N, Thompson M, King RM. The experience of living with a person with an eating disorder: the impact on the carers. Eating Disorders. 2005;13(4):327–44.

29. Hillege S, Beale B, McMaster R. Impact of eating disorders on family life: individual parents’ stories. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006;15(8):1016–22.

30. Hoek HW. Review of the worldwide epidemiology of eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):336–9.

31. Treasure J, Sepulveda AR, Macdonald P, Whitaker W, Lopez C, Zabala M, et al. The assessment of the family of people with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2008;16(4):247–55.

Comments