New clinical placement model in intensive care nursing – students’ experiences

Summary

Background: Clinical placements are a comprehensive and important component in the master’s programme in intensive care nursing and are crucial for students achieving the desired learning outcomes, which include knowledge, skills and general competence. Earlier research shows that the quality of clinical placements can be linked to the structure of the content, the supervision that students receive and the cooperation between educational institutions and the field of practice. To improve the quality of clinical placements, it is recommended that educational institutions and clinical practice jointly develop new clinical placement models. The master’s programme in intensive care nursing at OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University and the the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) at Oslo University Hospital have developed a clinical placement model aimed at improving the structure of the content in clinical placements, strengthening student supervision and promoting closer cooperation between the university and clinical practice.

Objective: The objective of the study was to evaluate a clinical placement model for students in a master’s programme in intensive care nursing.

Method: The study employs a qualitative approach, and includes semi-structured in-depth interviews with 13 students. The interviews were conducted in the spring and autumn of 2020 and the spring of 2021. The data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis of qualitative data.

Results: We identified five main themes in the analysis: 1) Students felt prioritised, 2) Students gained an overview of the department’s activities, 3) Students found there to be structure and continuity in the supervision, 4) Students felt self-assured and 5) Students found that their competencies and preparedness to respond effectively improved.

Conclusion: Students found that the clinical placement model helped them achieve the learning outcomes. The structure and content of the competency development programme fostered self-assurance in the students and continuity in the supervision, and integrated theory and practice through the cooperation between the university and clinical practice.

Cite the article

Harg I, Stubberud D, Solberg P. New clinical placement model in intensive care nursing – students’ experiences. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(98211):e-98211. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.98211en

Introduction

The Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research, and Education (NIFU) has studied clinical placements in nursing education in Norway. They found that the quality of the placements is crucial for students achieving the learning outcomes of the study programme (1).

Learning outcomes refer to what a person knows, can do and is able to accomplish as a result of a learning process. They are expressed in terms of knowledge, skills and general competence, and describe the qualification level students should have attained upon completing their education (2, 3). Clinical placements in the master’s programme in intensive care nursing are an important component in students’ competency development, accounting for 45 of the total 120 ECTS credits and covering a total of 30 weeks (4).

In the ‘Operation Clinical Placement 2018–2020’ project, Nokut investigated the quality of clinical placements in higher education within health studies during the period 2018–2020. The project revealed that clinical placements play a crucial role in helping students develop the competencies required for their future careers (5, 6).

The project also showed that one of the ways that clinical placements differ from practical job training is the opportunity they provide for students to reflect on their clinical experience within a theoretical framework (7). However, the quality of clinical placements is often considered variable and inconsistent (5).

Earlier research indicates that the quality of clinical placements can be linked to the structure of the content, the supervision that students receive and the cooperation between the university and the field of practice (2, 5, 8–10).

Academic supervisors and supervisors/coordinators in clinical practice emphasise the importance of a close cooperation between educational institutions and the field of practice. This cooperation is a key factor for improving the quality of clinical placements (11, 12). The field of practice aims to provide a welcoming environment for the students, but familiarity with the learning outcomes and content of study programmes varies (11).

Meanwhile, educational institutions aim to work together on planning and developing the content of study programmes with a view to ensuring up-to-date and practice-oriented learning. Close cooperation in integrating theory with practice is considered an important factor for improving the quality of clinical placements (2, 5, 7–12).

Universities Norway suggests that ‘new clinical placement models be developed, tested, evaluated and exchanged in an equal partnership between educational institutions and the field of practice’ (2, p. 6). Collaborative projects like this can bridge the gap between the field of practice and universities and help improve clinical placements for students (9).

New clinical placement models have been tested in the bachelor’s programme in nursing (13, 14) and in mental health care (15). However, we have not identified any studies evaluating new models for clinical placements in the master’s programme in intensive care nursing.

In cooperation with the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) at Oslo University Hospital (OUS), the master’s programme in intensive care nursing at OsloMet developed a clinical placement model aimed at improving the structure of the clinical placement content, strengthening student supervision and promoting closer cooperation between the university and clinical practice (16).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to evaluate a clinical placement model for students in a master’s programme in intensive care nursing. The research question was: ‘What are students’ experiences with a structured competency development programme for clinical placements?’

Method

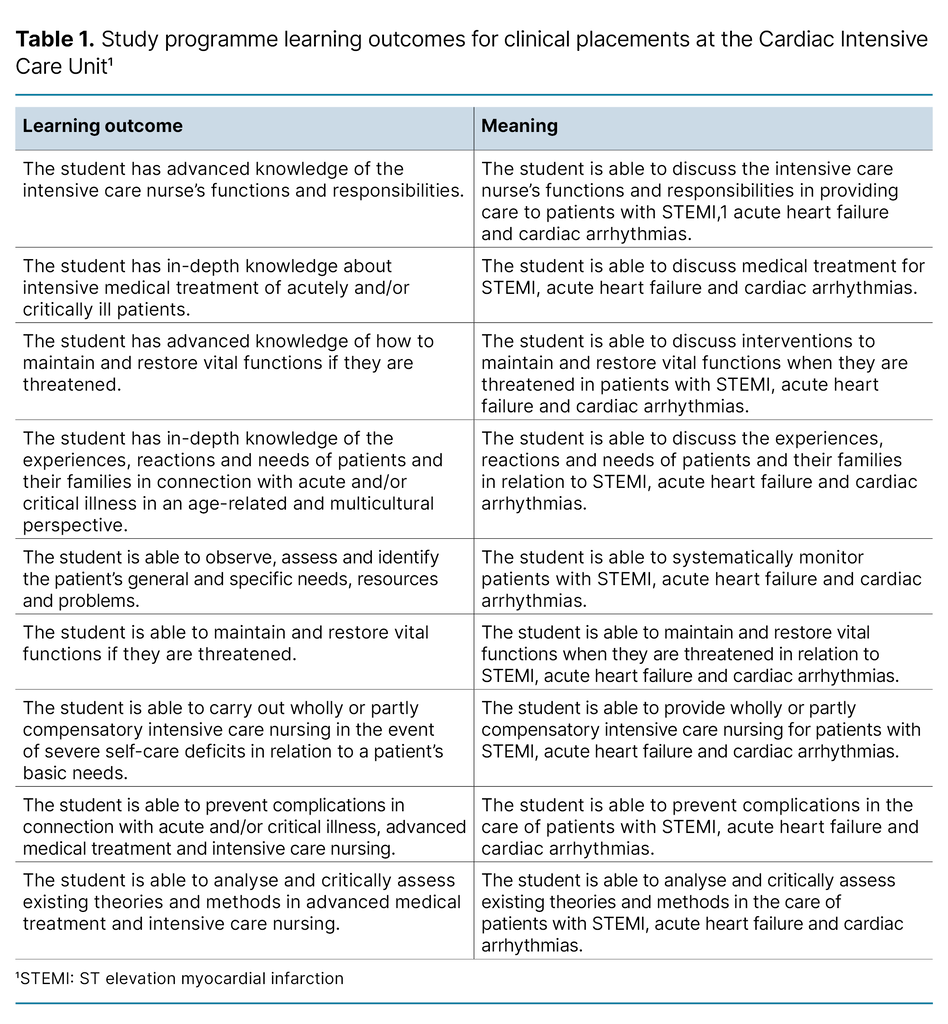

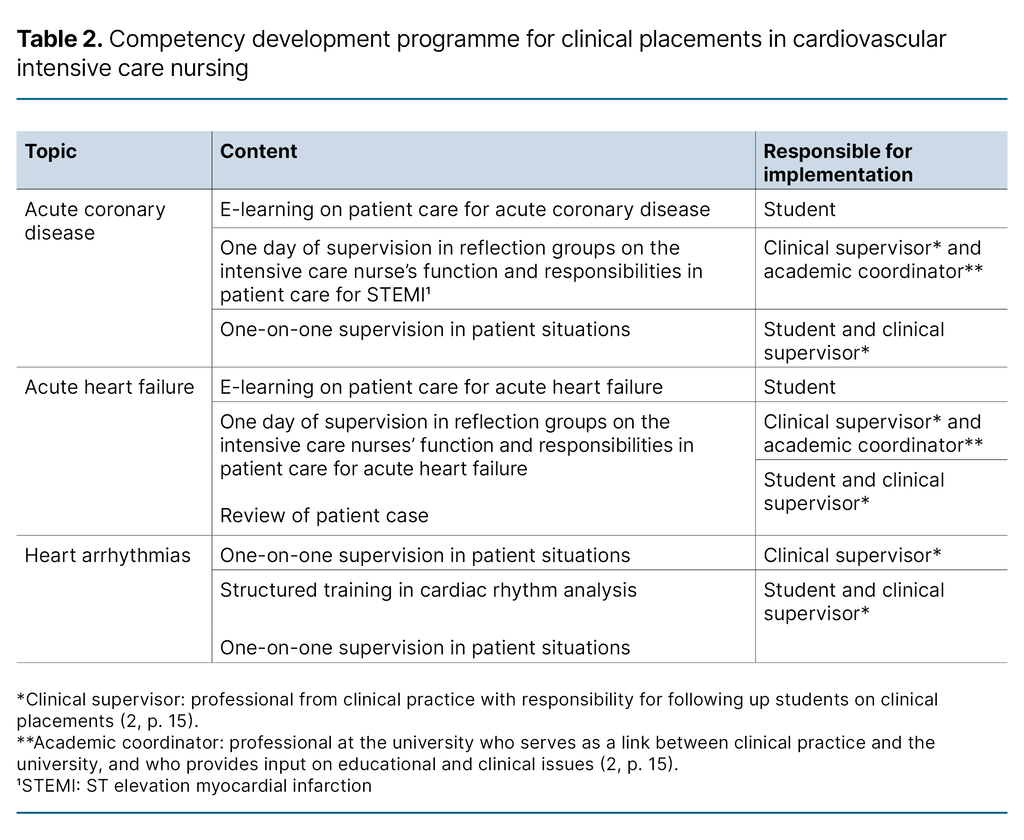

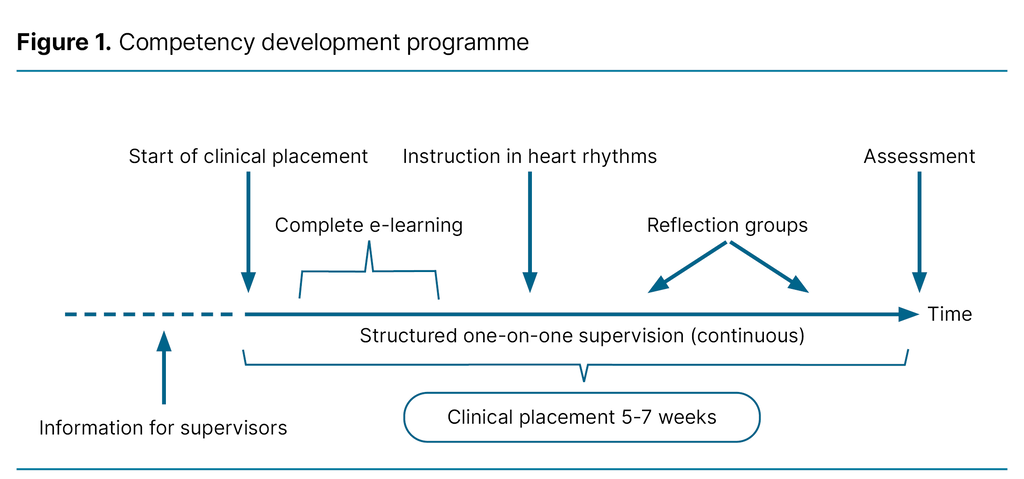

The clinical placement model included a competency development programme for patient care in acute cardiovascular conditions and is intended solely for the clinical placements at CICU. To ensure that students achieved the desired learning outcomes in the clinical placement (Table 1), and to create variation in the learning process, the project group employed various didactic methods:

- E-learning with a combination of interactive information pages and short video clips, where the third author provided instruction on topics in a relevant hospital setting.

- Reflection groups led by the first and second authors, with a review of a patient case in which students applied relevant research and experiential knowledge.

- Structured training in cardiac rhythm analysis, including practice in analysing various heart arrhythmias.

- One-on-one supervision in patient situations with a supervisor.

The purpose of the various methods was to foster motivation, engagement, practical application, variation, individualisation and cooperation (Table 2 and Figure 1).

The programme was implemented in the department in February 2020. The project group that developed the programme consisted of all three authors. At the time, the first and last authors held the roles of student coordinator and clinical nurse specialist at CICU, respectively, and represented the clinical placement department. The second author represented OsloMet in the project.

Design and method

We aimed to capture the students’ individual experiences with the competency development programme. We therefore chose a qualitative design method with semi-structured in-depth interviews, and reported the findings in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (17).

Interviews

We used an interview guide with open-ended questions based on the learning outcomes of the study programme. The guide was developed from the study programme description and the national curriculum for intensive care nursing (Table 1) (18, 19).

The last author conducted the interviews alone in the spring and autumn of 2020 and the spring of 2021. Unlike the first and second authors, who were part of the students’ supervision team, he had no close relationship with the students in clinical placement.

The interviews were held at the hospital immediately after the students had completed their clinical placements and received the result of their assessment. The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. Audio recordings were made but no field notes were taken.

Sample

The study participants were students in the master’s programme in intensive care nursing. They carried out clinical placements at CICU during the project period, from February 2020 to March 2021. The students spent between five and seven weeks in the department. Students in the master’s programme in intensive care nursing are registered nurses with at least two years of clinical experience in the somatic specialist health service.

During the project period, 14 students completed the competency development programme. Thirteen of these agreed to participate in the study and were subsequently interviewed.

Analysis

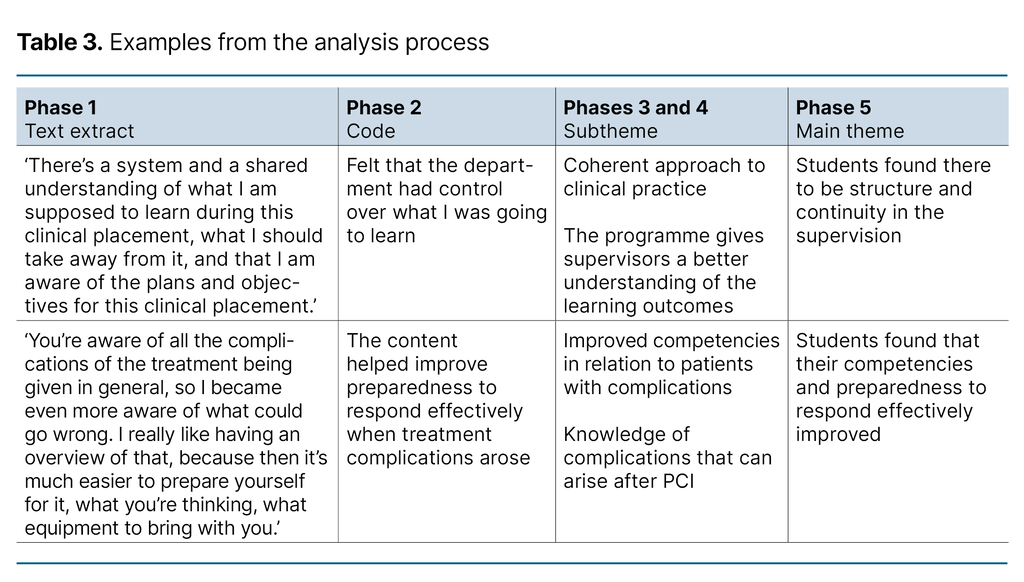

The interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. The first and second authors analysed the interview transcripts using Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis of qualitative data (20).

The analysis process is not linear and involves moving back and forth between the various phases of analysis: 1) Familiarisation with the data, 2) Generating initial codes, 3) Identifying themes, 4) Reviewing themes, 5) Defining and naming themes, and 6) Reporting the findings (Table 3).

Ethics

The study was defined as part of a quality improvement initiative at OUS. Sikt – Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research did not therefore need to be notified, but it was reported to the hospital trust’s data protection officer. The data protection officer at OUS recommended approval of the study (reference number 20/02076).

Participants were informed about the study on their first day of clinical placement. The interviewer repeated this information before the interview started. The students provided voluntary and informed written consent. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason and that all data collected would be de-identified.

Results

We identified five main themes in the analysis:

- Students felt prioritised

- Students gained an overview of the department’s activities

- Students found there to be structure and continuity in the supervision

- Students felt self-assured

- Students found that their competencies and preparedness to respond effectively improved

Students felt prioritised

The students noted that the department seemed well-prepared to receive them and that their assigned supervisors were familiar with the learning outcomes of the study programme. They felt that learning situations were specially facilitated for them, whereby they were allowed to participate in relevant patient cases:

‘The entire setup was notable – in a good way. I quickly got the impression that the department had prepared for our arrival. It stood out from other departments I’ve been in, also in my bachelor studies.’ (Student 1)

Students gained an overview of the department’s activities

CICU is a specialised department with several types of patient categories, where patients’ needs for monitoring and treatment vary. It can take time for students to familiarise themselves with the department’s core activities and understand what kind of patient care is needed.

The students felt that the content of the competency development programme helped clarify the department’s core activities. They were able to use e-learning before the clinical placement started. This gave them a good insight into the patient population and the relevant care needed for patients with an ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and acute heart failure:

‘We should use e-learning before we arrive […] I’ve done it twice, but I think it’s a good idea to do it first to understand the entire workflow in the department and the treatment.’ (Student 2)

In the reflection groups, they also described the supervision as important to understanding the treatment chain and what patient care is needed. After the group supervision, the students felt it was easier to understand and contribute to patient care:

‘The group supervision on STEMI was great because we’d been in clinical practice and seen patients. When we had the group supervision we could ask questions about the treatment we’d seen and experienced in practice. It was good to see if we had understood it correctly.’ (Student 3)

Students found there to be structure and continuity in the supervision

Several students emphasised that the competency development programme had a positive effect on the structure and continuity of the supervision. Knowing what to focus on and thus having the opportunity to make the necessary preparations helped them achieve the learning outcomes of the study programme. They also felt that the competency development programme facilitated a more coherent approach to clinical practice. Furthermore, the students found that the content of the competency development programme was varied and educational, with different didactic methods being used:

‘The way it is structured ensures that you get through your learning objectives. In earlier clinical placements, I’ve found that you can set as many goals as you want but end up with completely different patients, and things quickly become very fragmented.’ (Student 4)

Because of the defined content in the programme, students found that the clinical supervisors were able to ensure continuity in the content and taxonomy of supervision:

‘The programme makes it easier for clinical supervisors to help me experience the things I should, and not just be assigned tasks like personal care or things I already know. I don’t have to fight to create learning situations that I need. The supervisor is more aware of what learning situations I need.’ (Student 2)

E-learning enabled students to refresh their knowledge throughout their clinical placement:

‘The videos were really educational. You could watch them repeatedly. The content in the videos was very clear. Very well explained. It helps when you watch them again, a hundred times, then it sticks.’ (Student 5)

In terms of other structural factors, students characterised the cooperation between the department and the university as positive:

‘It’s great that the university and clinical practice cooperate on the organisation of clinical placements and what we need to do.’ (Student 8)

Students felt self-assured

They pointed out the importance of feeling self-assured during clinical placement in order to actively participate in providing patient care. Factors that fostered self-assurance included the following:

- The department was prepared and welcoming.

- E-learning enabled students to prepare themselves.

- The content of the clinical placement was clearly defined and organised.

Student 1 noted the following: ‘For me as a student, it was very reassuring that you had set up a plan for us. How we would systematically go through things, like STEMI and cardiogenic shock.’

Student 6 expressed the following: ‘After going through the patient case for acute coronary disease in group supervision, I felt more self-assured in the PCI [percutaneous coronary intervention] lab. I felt braver about getting involved.’

Students found that their competencies and preparedness to respond effectively improved

The students felt that their competencies improved through, for example, acquiring knowledge and skills in patient care for STEMI and acute heart failure. They felt that the content of the competency development programme helped them form a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s problems and needs. E-learning provided them with an overview of the knowledge and skills the department expected them to acquire.

Through group supervision, they gained a deeper understanding and had the opportunity to reflect on their own experiences in patient situations:

‘I remember sitting at the end of the day thinking how much I had learned about seeing the whole picture. Recognising the patient’s basic needs. I had to reflect on what might complicate the situation. The learning was more in-depth.’ (Student 1)

The patient’s condition, such as in the case of STEMI for example, can change suddenly. In the interviews, it emerged that the competency development programme helped to highlight the complications that could arise when treating patients. This made the students feel that they were prepared to respond effectively and carry out the recommended interventions:

‘You’re aware of all the complications of the treatment being given in general, so I became even more aware of what could go wrong. I really like having an overview of that, because then it’s much easier to prepare yourself for it, what you’re thinking, what equipment to bring with you.’ (Student 6)

Discussion

The results show that the students had positive experiences with the competency development programme. They felt that the structured content in the clinical placement, continuity in supervision and close cooperation between the university and clinical practice helped them achieve the learning outcomes.

Structure

The structure of clinical placements impacts on quality (2, 5, 8–10). Structure refers to how the various elements of clinical placements are integrated into a cohesive whole and how this whole is organised.

The competency development programme helped students gain a comprehensive understanding of the care needed for patients with acute and/or critical coronary disease. The students thus felt they achieved the learning outcomes of the study programme. According to Norway’s Ministry of Education and Research, clinical placements should facilitate the achievement of study programmes’ learning outcomes (10).

Research shows differing opinions on the effect of e-learning in developing competencies (21–23). However, the students in this study found e-learning useful as it served as a knowledge resource that could be accessed throughout their clinical placement.

Self-assurance promotes learning, including in clinical placement. Self-assurance in clinical placement stems from being acknowledged and supported, and having a well-organised structure, mutual expectations and predictability. Predictability is linked to clarity and structure. Students who are self-assured are more willing to take an active role in their learning and therefore make better use of their resources and work more consciously toward their learning outcomes (24).

According to the students in the study, the structure and systematic approach of the competency development programme was reassuring. The fact that the department was prepared and welcoming also contributed to this experience. The structured organisation of the clinical placements made them feel prepared, enabling them to take an active part in patient care.

Supervision

The quality of supervision that students receive affects the overall quality of their clinical placement (1, 2, 5, 8–10). To achieve the learning outcomes of their study programme, students need competent supervisors. The clinical supervisors assigned to students play a crucial role in their learning process.

The students found that the competency development programme helped familiarise their clinical supervisors with the study programme’s learning outcomes. As a result, learning situations were arranged and adapted according to the students’ needs. The students experienced structure and continuity in their supervision.

The opportunity to reflect on patient situations that students have encountered is important for ensuring that clinical placements serve as educational experiences rather than just practical job training (7, 9, 25). However, finding time for reflection during patient care is not always possible. The physical and mental condition of patients with an acute and/or critical illness may limit this opportunity.

Groups of three to four students were taken out of the department for two full days of group supervision. The students in the study reported that these supervision sessions provided a space for reflection, allowing them to connect theory with practice. They worked through patient cases with their academic and clinical supervisors, which helped confirm their understanding of what they had learned and highlight any knowledge gaps.

Reflection groups with few students, led by an academic supervisor and/or clinical supervisor, can provide a space for students to engage in professional reflection during their clinical placement. This form of supervision can motivate students and help them connect theory with practice (9, 25).

Allocating time for reflection may mean that students experience fewer patient situations, but none of the study participants raised concerns about this.

Cooperation between educational institutions and the field of practice

The interviews revealed that the students viewed the cooperation between the university and clinical practice in a positive light. According to Hatlevik and Havnes, students perceive their studies to be of a higher quality when there is a clear connection between what they are taught at university and what happens in clinical practice (26).

Hatlevik asserts that this connection is crucial for students achieving the learning outcomes of their study programme and ensuring continuity and quality in their education (27). He also claims that a connection between theory and practice can be established by explaining how theoretical knowledge informs various aspects of professional practice (27).

Group supervision in the competency development programme is an example of this. In the group supervision, challenges from clinical practice were discussed in light of theory with professionals from both the university and clinical practice. The students reported that the group supervision helped them gain a more comprehensive understanding of the patient’s situation and the care they needed. This gave them the confidence to become actively involved in patient situations.

Clinical supervisors are calling for closer cooperation with educational institutions. Dialogue about the curriculum, learning outcomes and other framework conditions helps create a more comprehensive understanding for students, better preparing them for the professional challenges they will face in clinical practice (2, 28).

The cooperation between the university and clinical practice helped ensure that students perceived their clinical supervisors as well-prepared, with a good understanding of the learning outcomes for the clinical placement, thereby fostering students’ competency development.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study has a number of strengths:

- We interviewed students in three different cohorts of the competency development programme over a period of 13 months.

- The participants were interviewed immediately after completing their clinical placement, when the competency development programme was still fresh in their minds. This may have reduced the risk of bias.

- The interviewer was well acquainted with the study programme’s content and learning outcomes for the clinical placement, as well as the field of study and the content of the competency development programme.

None of the students reported having negative experiences in relation to the competency development programme. However, the study has several potential weaknesses that may have unintentionally contributed to more favourable findings:

- The study participants were students, which may have created an imbalanced power dynamic between the researchers and the participants. The project group consisted of representatives from the university and clinical practice, which are the entities responsible for assessing whether the students have passed their clinical placement. We therefore conducted the interviews after the students had completed their clinical placement and been informed of the result of their assessment. The interviewer was not involved in the student assessments. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the students felt under pressure to be positive.

- The interviewer played a central role in the e-learning videos. This may have made it difficult for the students to criticise that part of the competency development programme. Otherwise, the interviewer had no other relationship with the students during their clinical placements.

- We developed and implemented the competency development programme and then researched our own field. We cannot rule out the possibility that our preunderstanding may have influenced the results.

- The COVID-19 pandemic started shortly after the competency development programme was implemented. This led to some minor changes in the programme, such as one of the reflection groups being held remotely instead of in person. The interviews were held in person at the hospital, as planned. We cannot rule out the possibility that the pandemic may have impacted on the results.

Conclusion

The study shows that the students felt the clinical placement model helped them achieve the learning outcomes of the study programme. The structure and content of the competency development programme fostered self-assurance in the students and continuity in the supervision, and integrated theory and practice through the cooperation between the university and clinical practice.

A structured programme for clinical placements can help students view the placements as meaningful and as a suitable setting for achieving the learning outcomes of their study programme. We believe the results may be transferable to undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate nursing students.

Funding

The clinical placement model was developed with the help of partner funding from Oslomet.

During the study, the first and last authors held the roles of student coordinator and clinical nurse specialist at CICU, respectively, and represented the clinical placement department.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments