Parents’ experiences of losing their newborn child in intensive care

Summary

Background: Parents’ grief when their newborn child dies can involve anger, guilt, fear, emptiness, loneliness and depression. Admitting a child to an intensive care unit (ICU) places an additional emotional strain on the parents as many of the typical parenting tasks can be difficult to carry out due to the child’s medical condition. The parents’ bond with their child will be affected. Family-centred care (FCC) aims to involve parents in the treatment of their child. This entails close cooperation with healthcare personnel, but challenges such as space constraints, the varying skills of staff and the frequent need for medical procedures can hinder FCC in critically ill neonates. Research is limited on parents’ experiences with the unexpected death of a neonate in an ICU.

Objective: To explore parents’ experiences after their newborn child unexpectedly died while in an ICU.

Method: The study employed a qualitative exploratory and descriptive design. We conducted individual semi-structured interviews using a theme-based interview guide to collect data. The analysis took the form of a thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke.

Results: The sample consisted of eleven parents, with five fathers and six mothers representing seven children. The analysis identified three main themes, which describe in different ways the characteristics of the parents’ experiences after the unexpected death of their child: 1) An emotional rollercoaster, 2) The importance of the relationship between the child, parents and nurses and 3) Parents’ participation at the end of the child’s life.

Conclusion: Parents who lose their newborn child experience a variety of emotions. They go from joy over the child’s birth to anxiety and worry in a chaotic intensive care environment, where life feels unreal and the severity of the situation is difficult to comprehend. They need support and understanding from the nurses, and they need the opportunity to be present for and establish a bond with the child – to be parents and create memories. The findings suggest that it is important to tailor the support and be sensitive to parents’ needs, particularly in challenging decision-making processes. The study underpins the importance of implementing FCC in ICUs that treat critically ill neonates.

Cite the article

Magnussen T, Tømt C, Larsen M, Sørensen K. Parents’ experiences of losing their newborn child in intensive care. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(94677):e-94677. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.94677en

Introduction

An average of 6000 neonates are treated in neonatal units in Norway every year (1, 2). Medical advancements mean that many premature and newborn babies with congenital conditions and illnesses are given intensive care (1). This means that the specialist health service now treats children with more severe health problems than previously, which increases the demands on the competence of healthcare personnel (2). Despite highly specialised treatment, neonates can die during intensive care (1).

Losing a child is described as one of the most painful and traumatic experiences a person can endure (3). The death of a neonate in an intensive care unit (ICU) can occur after a gradual deterioration in their condition, or acute situations can lead to them dying unexpectedly. Parents’ grief can then involve anger, guilt, feelings of loneliness, fear and emptiness (3). Previous research indicates that parents with a neonate in an ICU experience loneliness, stress and depression, as well as emotional distancing in the final moments of the child’s life (4).

A hectic ICU with a large staff and advanced technology can feel alien and unwelcoming to parents (5). Helplessness in not being able to protect the infant and the loss of control associated with the passive parental role can mean that parents feel a lack of closeness and belonging to their child (6). Parents’ involvement in decisions related to end-of-life care appear to impact on their grieving process and psychological well-being long after the child’s death (7).

In current nursing practice, family-centred care (FCC) is described as a cornerstone of paediatric nursing (8, 9). The framework is based on ten principles developed during a conference in 1992. This initiative involved doctors and parents whose critically ill children had been treated in a neonatal ICU. The discussions also included other occupational groups, such as nurses (10). The core values in the framework are respect, dignity, participation and information sharing in interactions with children and their families (9).

Caring for a newborn child in a neonatal unit is therefore not only about medical treatment but also about supporting and caring for the family as a whole. The main constituent of FCC is the collaboration between the healthcare personnel and the family. Parents and other family members are encouraged to be actively involved in the decision-making process and the care of the child. For healthcare personnel, FCC thus includes providing parents with information, explaining treatment options and respecting their wishes and concerns (11).

However, parenting tasks such as feeding, washing and skin-to-skin contact (kangaroo care) (12) can be difficult to carry out in the neonatal period due to the child’s medical condition. A Norwegian study showed that being unable to spend time alone with their child was a significant source of parental stress in the neonatal period (13).

Our initial literature search indicated that parents’ experiences of unexpectedly losing a newborn child in intensive care is an under-researched area. Previous research in the field focussed on parental experiences related to stillbirth, palliative care in the neonatal period and the loss of older children (3, 15–18). Increased knowledge and competence among nurses caring for critically ill neonates and their parents can help ensure that families receive more tailored support and guidance in the future.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was therefore to explore parents’ experiences after their newborn child unexpectedly died while in an ICU. We aimed to answer the following research questions:

- What are parents’ needs when they lose a newborn child in an ICU, and how are these needs met?

- How do parents perceive their relationship with the nurses in such a situation?

Method

Design

This qualitative study employed an exploratory and descriptive design. In accordance with Malterud’s recommendations (18), we conducted individual interviews to obtain data on sensitive topics. The study reporting adheres to the checklist ‘Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research’ (COREQ) (19) (Appendix 1).

Recruitment and sample

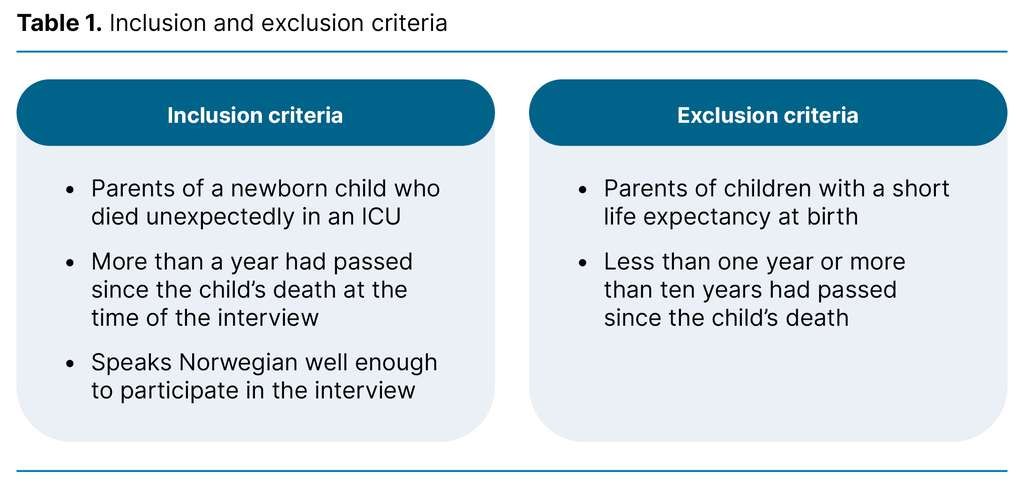

Participants were recruited through the National Association for Unexpected Child Death and the Norwegian Association for Children with Congenital Heart Disease. The associations disseminated information to their members via their online channels and information letters (Appendix 2 - in Norwegian). Those who wanted to participate contacted the first authors (18). None of the authors knew any of the participants from the child’s stay in an ICU. Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted between December 2021 and February 2022 by the first authors, who were master’s students at the time. Both are female nurses with experience from a neonatal ICU. One asked questions and was actively engaged in the conversation, while the other noted impressions and non-verbal communication. The interview guide was formulated based on the objective of the study, theory and the authors’ personal experiences (Appendix 3 - in Norwegian)

The interview guide was developed by the first authors and tested in a pilot interview that was not included in the study. No subsequent changes were made to the interview guide. The parents were mostly allowed to speak freely about their experiences, but the interview guide ensured that the conversation covered the relevant topics.

We attempted to establish a safe atmosphere by allowing the participants to choose where to be interviewed. Four interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom, two were conducted in connection with a seminar organised by the National Association for Unexpected Child Death, and the remaining five were conducted at the participants’ homes. The interviews lasted from 45 to 150 minutes and were recorded on audio tape.

Analysis

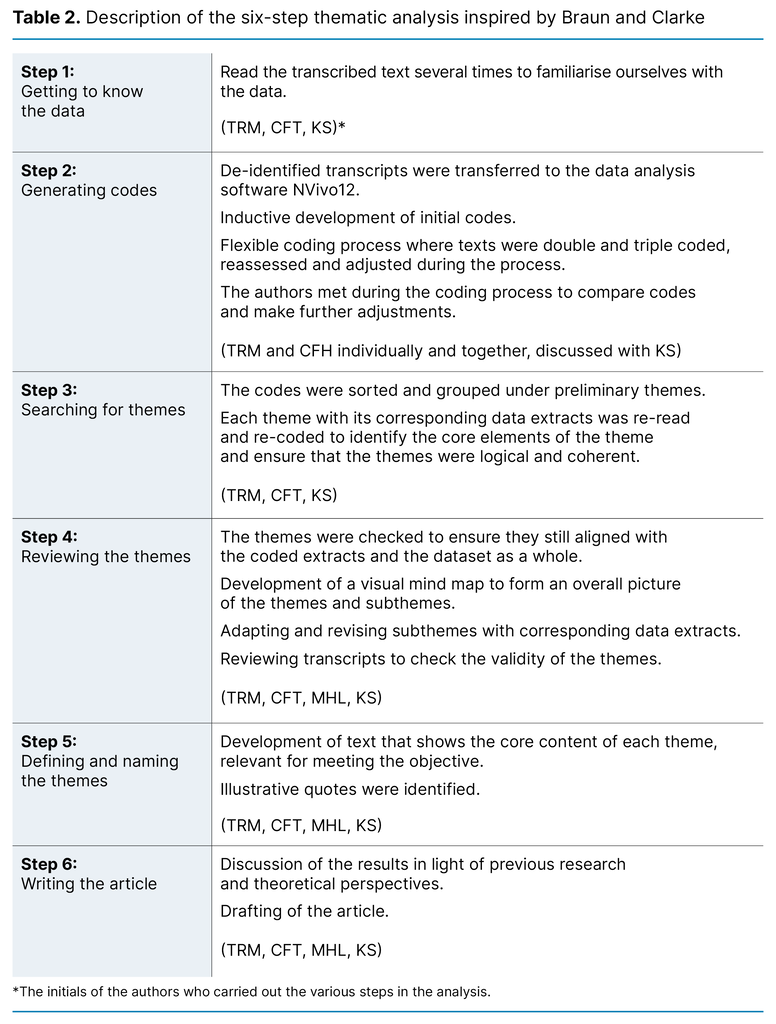

The first authors transcribed the interviews, resulting in 73 pages of text. The transcribed text was coded inductively and further analysed using thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke (20). We analysed the parts of the text that we considered relevant to our objective. NVivo 12 data analysis software was used to aid the organisation and analysis of the data. Table 2 shows the analysis process and the authors’ contributions.

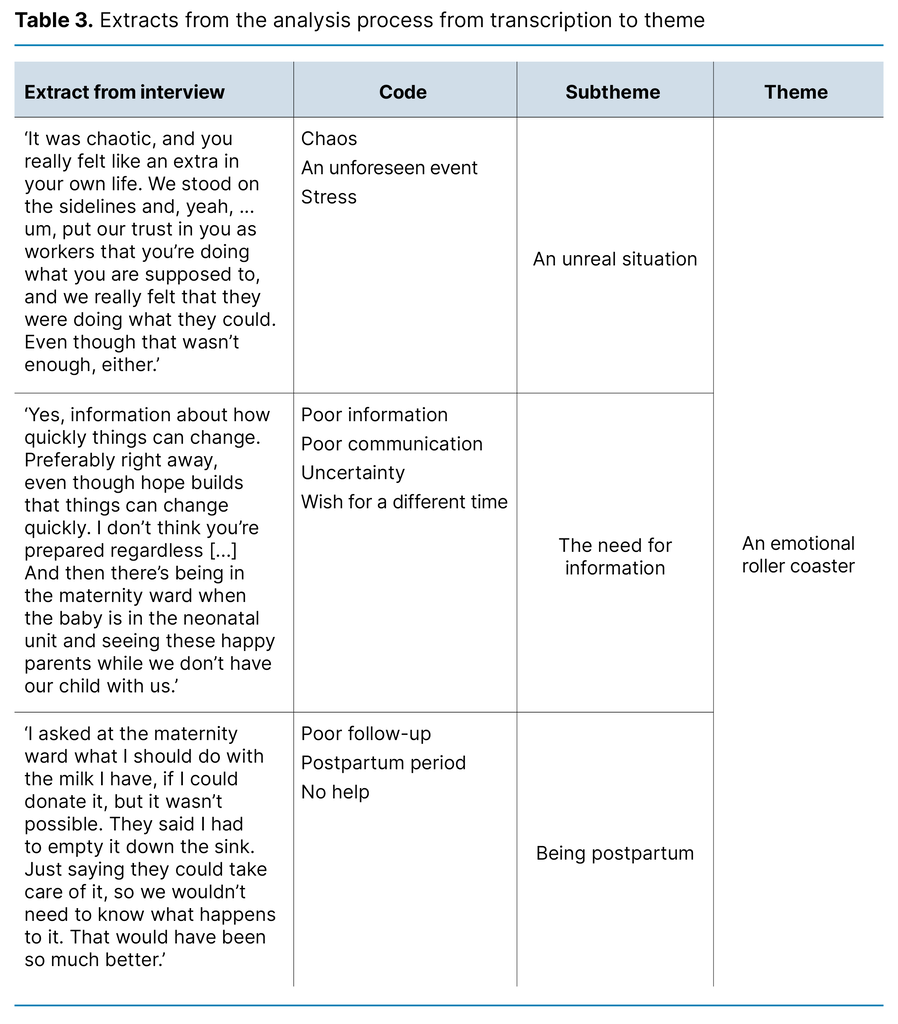

Table 3 is an extract from the analysis process, with text coding, subtheme definition and a final theme.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference number 353568, and conducted according to research ethics guidelines for particularly vulnerable groups (21). Potential participants received oral and written information about the study and were informed that participation was voluntary. All the parents who contacted us wanted to participate in the study, and none withdrew at any point. All participants provided written consent prior to the interview and were reminded that they could withdraw both during and after the interview.

We decided to hold individual interviews because talking about losing a newborn child can be difficult. The parents were asked to recount the period around the child’s death, which could evoke painful memories and constituted a psychological burden. Since the participants were recruited through the National Association for Unexpected Child Death and the Norwegian Association for Children with Congenital Heart Disease, they could be offered further follow-up through these associations.

The participants expressed a strong desire to share their experiences, and found the interview situation to be positive. All data were de-identified and treated confidentially in accordance with procedures at Lovisenberg Diaconal University College, which was the institution responsible for data management.

Results

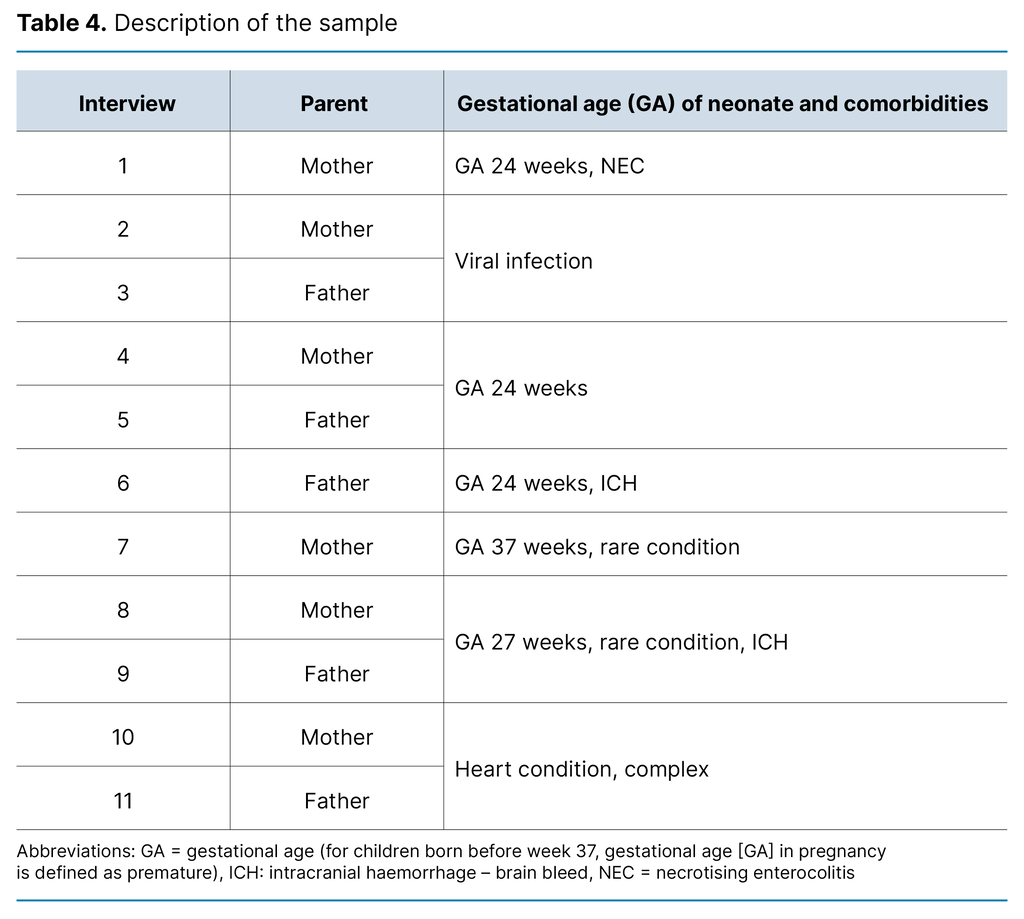

The sample consisted of eleven parents representing seven children. The parents were aged 24–40 years. At the time of interview, between one and five years had passed since the death of their child. The children were admitted to the ICU unit for periods ranging from two days to seven weeks. Three families were hospitalised during the COVID-19 pandemic. In three of the interviews, the mother and father were interviewed together. For further characteristics of the sample, see Table 4.

We identified three main themes that summarise the parents’ experiences of the ICU when their newborn child died: ‘An emotional roller coaster’, ‘The importance of the relationship between the child, parents and nurses’ and ‘Parents’ participation at the end of the child’s life’.

The results are illustrated with quotes from the interviews.

An emotional roller coaster

The parents described how they felt that the entire situation was unreal and found it difficult to comprehend the severity of the situation. From being pregnant and looking forward to becoming parents, they were thrown into an unknown world characterised by chaos and despair:

‘An alarm button was pressed, and suddenly there were ten people in the room to administer lung support, magnesium and drugs to stop my contractions. A helicopter was also sent for, and I was there all on my own because I was just supposed to be having a check-up.’ (Mother 4)

Some participants described how their hope fluctuated with positive information one moment and a sudden critical development in the child’s condition the next. A cerebral haemorrhage in the premature neonate or complications during surgery were examples of events that could abruptly turn the hope of a happy future into despair.

Others mentioned the absence of conversations specifically about how critical the situation actually was for the child, which would have enabled them to prepare themselves for how quickly a seriously ill child’s condition could change:

‘I wish we had been given more information about what to expect. And perhaps a bit more pessimism or realism about how quickly things could change.’ (Father 6)

This father expressed how healthcare personnel had a ‘it’ll be alright attitude’, and that the information they were given was too positive. Others believed that positive information offering hope was important:

‘I got a heads up from a paediatrician [about] how extensive this would be, because it was critical, but there was also an overall optimism. Knowing that they had faith even though it was critical was good.’ (Mother 1)

The parents pointed out the importance of specific details, which provided predictability even when the information itself was negative.

Several mothers felt they were not viewed as postpartum. They talked about a body that bore the signs of pregnancy and childbirth, even though they did not have a child to hold in their arms:

‘I was postpartum but had no child, and my body had been through something insane. I kind of had no postpartum identity because I had lost my child.’ (Mother 2)

The mothers had wanted more information about where and how they could express milk while the child was alive, and about how to stop milk production when the child died. Some talked about the challenges they faced following a caesarean section and reported a lack of information about wound management. They felt that their postpartum identity was disregarded and that they were forgotten by the healthcare personnel, especially after the child’s death.

The mothers had wanted more information about where and how they could express milk while the child was alive, and about how to stop milk production when the child died. Some talked about the challenges they faced following a caesarean section and reported a lack of information about wound management. They felt that their postpartum identity was disregarded and that they were forgotten by the healthcare personnel, especially after the child’s death.

The importance of the relationship between the child, parents and nurses

The parents described how the nurses helped them bond with their child by including them in washing and nappy changing, or showing them how to touch the child’s head and hands. The small things were important and helped them feel like parents amid the wires and machines:

‘One of the nicest memories is thanks to a nurse. She enabled us to be parents and brought some breast milk for him to taste – after [it] had been confirmed that he would die. He loved that.’ (Mother 1)

Several participants mentioned that they wished they had more physical contact with the child. In retrospect, the experience of holding the child was very important, even when the child was heavily wired up and unstable. The parents described eye contact and touch as crucial for bonding with their child.

Continuity among the nursing staff allowed the parents to feel a sense of security when familiar nurses cared for their child. They also mentioned how familiar nurses noticed changes in the child sooner and understood the child’s needs better. This was important for the parents to dare to entrust their child to the nurses. Several parents expressed gratitude. One said the following: ‘The nurses have a special place in our hearts. They made the stay as good as possible’. (Mother 8)

Some parents talked about how nice it would have been for other family members, such as grandparents, aunts and uncles, to also have seen their sick child. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, some families were offered the opportunity to gather, for example, during a baptism:

‘Yes, we had an emergency baptism the day before he died, and then we were allowed to have visits from my grandparents, my mother and my aunt. So everyone was present during the baptism and wore a face mask. So, luckily, we were able to have a small ceremony.’ (Mother 2)

Restrictions were more stringent for other families, such as a father who was not allowed to spend any time with his child at all. The mother of this child described tremendous sadness over not being able to be together as a family.

Some parents had not been treated in a way that met their needs during the stay:

‘When we arrived at the hospital, no one came to meet us. They said on the phone that a nurse would be ready for us, but that wasn’t the case.’ (Mother 1)

They felt abandoned and were shocked at having a critically ill child. They also described episodes where nurses took coffee breaks and discussed their private lives right next to the critically ill child. The noise from this disturbed the peace for the parents spending time with their child and made them unsure whether they could trust the nurses.

Many parents talked about the importance of memories. These could involve specific actions and/or different types of physical objects to take home:

‘They gave us memory books and plaster casts. We needed that. I think you need physical things.’ (Mother 2)

The parents also talked about the importance of the nurses celebrating all the milestones in their baby’s life, and that they received certificates for each event. Parents who did not have physical memories described this as particularly painful:

‘What made it worse was that they actually made such memory books. I don’t know if they misplaced ours or if they never made one for us, but nobody found it. It would have been nice to have now.’ (Mother 10)

Parents’ participation at the end of the child’s life

The parents described the importance of witnessing their child’s deterioration. It gave them time to prepare for and accept the child’s death. The parents described the importance of the nurses’ support and facilitation during this period:

‘He died lying between us, and even though we were just lying on that sofa bed waiting for his heart to stop beating, that was also nice. It was supposed to be the three of us! That’s how it started, and it felt right that that’s how it should end. It was nice to be able to take everything at our own pace.’ (Father 6)

Other parents did not have time to prepare for their child’s death. One child died unexpectedly during surgery, and some parents recounted the swift transition from the decision to terminate treatment to actual termination:

‘From the moment it was decided that it was over and we were going to switch off the ventilator, things happened quickly, so we struggled to keep up.’ (Mother 7)

Parents who were not present when the child died said that they had wanted to be given specific details immediately, not six months later during the review of the autopsy report:

‘I wish they had told us how long they performed life-saving treatment for, and that they did chest compressions for fifteen minutes. That they actually gave him a chance.’ (Mother 1)

Views on the decision-making process regarding the termination of treatment differed. Some fathers felt it was important to be involved in the decision to terminate treatment, but that confirmation from healthcare personnel was essential in this process:

‘We were very involved in the decision to stop treatment. It was our choice. But what was so nice was that the person who met us on arrival came and said he thought we had done the right thing, and that’s reassuring because we haven’t then done anything wrong.’ (Father 6)

Other parents had not been involved in any decisions but had to simply accept what had been decided. Consequently, they felt like their opinion did not matter. One mother believed that this had negatively impacted her grieving process. In contrast, some parents felt too involved in the decision to end treatment. They were given choices they were unable to make, such as deciding the timing of the termination. They believed healthcare personnel should set the parameters for the termination:

‘We were far too involved. It was like: “When does it fit in your calendar for your daughter to die?”’ (Mother 7)

The parents described different experiences from the actual termination. The individual needs of some couples differed, with one parent wanting more time with the child while the other did not. Several parents were given the opportunity to help care for the child and take pictures. Some were given a separate room during treatment termination, where siblings and grandparents could also come and go as they pleased and spend as much time together as possible, both before and after the child’s death:

‘We were holding him when he died. Before he died, my father was able to hold him for a little while – and then he died in my arms, and then they kind of unhooked – the machine. Yeah, I really felt it there – I’ve never seen a dead person for real before, only in films.’ (Mother 8)

Discussion

The main findings of the study demonstrate how the parents’ emotions fluctuated between hope and despair while their newborn child was undergoing intensive care. The many small things that contributed to them feeling like parents, such as being involved in taking care of the child, experiencing physical and eye contact, or giving them a few drops of breast milk, were considered very important retrospectively. However, the overall experience was characterised by both positive and negative events throughout the process. Information flow and involvement in the decision to terminate treatment appear to be two important factors in the overall experience.

Specific details can contribute to a sense of control in a chaotic situation

Our findings correspond with those of previous studies and demonstrate the considerable need for information, support and care among parents of premature and unexpectedly critically ill children. However, these parents’ experiences of how these needs are addressed differ (8).

Our study showed that continuous information and specific details about the child’s condition could contribute to a sense of control in a chaotic situation. Daily updates with the opportunity to ask questions, as well as being able to interact with a small, dedicated team familiar with the child, helped reassure parents and gave them a positive experience of participating in the care of the child. This finding is consistent with the principles of family integrated care (FICare), which is an extension of family-centred care (FCC), particularly aimed at neonatal intensive care (22).

Nurses are tasked with providing support and guidance to parents on how to best care for their child, ensuring that they become confident caregivers. The aim is to improve and increase parental involvement and their partnership with healthcare personnel in relation to the child’s daily care. Previous studies have shown that when nurses repeat information and allow for questions without using advanced medical terminology, parents perceive them as good nurses (17, 23).

However, we also found that some parents experienced conflicting or vague information about the severity of their child’s condition, and that they were therefore not prepared for the possibility of the child dying. This sometimes made them feel uncertain about previous information they had been given and the actual treatment of the child. Previous studies have also shown that honest and clear information is an important factor in parents understanding the overall situation and the child’s condition (14, 16).

Communication impacts on perceived involvement in care and decision-making

Within FCC, information sharing and parental involvement in the child’s treatment are considered integral to the care of parents with critically ill neonates (3, 8, 9). Research on family members of adult intensive care patients in Norway shows similar experiences to the parents in our study. These family members wanted to help make the patients feel more secure during the ICU stay, and they considered their efforts an important resource. A calm atmosphere, trust in the healthcare personnel and private visits with the patient enabled the family members to play an active role, where they could support and care for the patient (24).

Our findings suggest that nurses play a crucial role in fostering a good relationship between parents and their critically ill newborn child. Parents who felt involved in the treatment and care of the child experienced a positive parent-child bond, which is important knowledge for nurses working in FCC. Previous research has shown that spending time with the newborn child is highly valued, and closeness and support from healthcare personnel strengthen the parental role (3, 14).

How well parents bond with the child is described as important in the period following the child’s death and impacts on parents’ health and grief reactions (16). However, our findings also showed that some parents did not feel as well cared for by the nurses and doctors. They described how one negative event or incidence of poor communication could negatively impact on the overall ICU experience. This finding aligns with a Norwegian doctoral study examining the experiences of family members of adult ICU patients (25, 26).

The results showed that while the families were satisfied with the respect and consideration demonstrated by doctors and nurses towards patients, they were not satisfied with the communication, particularly between themselves and the doctors. The doctors provided information, but they often used medical jargon that was difficult to understand, and families called for more feedback about the patient’s condition and simpler language. In a Dutch study, parents found that communication problems about death and conflicts with healthcare personnel had a particularly negative impact on the overall experience (23).

The relationship between parents and healthcare personnel can often change during the ICU stay. Initially, healthcare personnel tend to be the dominant party, before they become a team together with the parents. In the final phase, where the child dies, the healthcare personnel gradually withdraw from the relationship (23). In our study, the parents describe interactions with healthcare personnel in different phases of the ICU stay. In cases where the child suddenly became critically ill and died, it may have been in an early phase where the parent-staff relationship had not yet developed into a solid team.

Creating memories and preparing parents for the end are important nursing tasks

In line with other studies (6, 14), our study shows that tangible memories such as photos, footprints or other mementos can help create a bond between the parents and child, which subsequently becomes a valuable memory. The parents in our study who had no tangible memories and/or did not get to spend enough time with their child emphasised the importance of nurses ensuring that parents have such memories and meeting their needs. They subsequently experienced additional grief, helplessness, psychological stress and bitterness towards the healthcare personnel.

These findings are consistent with a mixed-methods study (27) in which parents who did not have the opportunity to say goodbye to their child experienced prolonged grief and depression. It negatively affected their ability to work and to function in daily life. Such negative parental reactions also align with findings from a Canadian study, where fathers who did not see their child during the ICU stay felt a sense of helplessness, anger and exclusion (28). These fathers felt deprived of memories and valuable time that they would never get back.

The findings showed how having time to prepare for the child’s death impacted on the parents. The parents of children who gradually deteriorated had more time to prepare for an unwanted outcome. They seemed better equipped to participate in decisions about terminating treatment. Parents of children with more acute clinical courses had more negative experiences with participation and also mourned this after the child’s death. Our findings align with what the literature says about the importance of parental involvement, including in relation to such difficult and tough decisions (29).

Decisions to terminate the treatment of a child in a neonatal unit are, nevertheless, extremely complex and emotionally challenging (30), as emphasised by the parents in our interviews. Encouraging parents to be involved in the decision-making process can have implications for the grieving process, including in the longer term (7, 17, 31).

However, our findings show that the extent of parental involvement and the decisions they find too difficult vary greatly among individuals. When the doctor responsible for the child’s treatment makes a clear final decision, the parents can focus on spending time with their child during the crucial moments and start the grieving process (32). Feeling responsible for the decision to terminate treatment can have a negative impact on parents’ mental health (33).

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of the study is the participation of both mothers and fathers, as similar studies have often only included mothers. The diversity in participants’ demographics, age and time since the child’s death helped provide a nuanced array of experiences among the parents. A further strength is that the experiences of parents represent a range of neonatal units from different parts of Norway.

It may also be a strength that all the authors have experience in paediatric nursing in an ICU, and that the first two authors conducted the interviews together. It could be argued that our sample size is somewhat limited. However, we had a narrow focus in that we aimed to achieve a deeper understanding of a very specific phenomenon. According to Malterud et al., a narrow focus requires fewer participants than a broader approach to a phenomenon (18, 34).

Malterud also emphasises that if participants have expertise in the field and rich experiences they wish to share, a limited sample size will also mean good information power, which was highly relevant for our study.

It may be a limitation of the study that the use of interest organisations to recruit participants might have resulted in a sample of participants in a more advanced stage of the grieving process than parents not affiliated with such organisations. However, using a strategic sample could also be interpreted as a strength of the study. It may have contributed to generating richer and more detailed data, which is important in qualitative research where the aim is to achieve depth and understanding (18).

Nevertheless, there may have been experiences and nuances that we failed to identify. Preconceptions may have influenced the results. However, our detailed descriptions of the method, sample, context and results, including quotes from participants, underpin the study’s credibility (15).

Conclusion

Parents who lose their newborn child in an ICU experience a range of emotions, from joy over the child’s birth to anxiety and worry in a chaotic intensive care environment. Life feels unreal, and the severity of the situation is difficult to comprehend. The parents need support and understanding from nurses. They need to spend quality time with the child in order to form a bond – to be parents and create memories.

The findings suggest that it is important to tailor the support and be sensitive to parents’ needs, particularly in challenging decision-making processes. The study underpins the importance of implementing FCC in all ICUs that treat critically ill neonates.

Further research is needed on the role of parents in the decision-making process regarding the potential termination of medical treatment for critically ill neonates. The same applies to the follow-up of parents following such a death.

Therese Rohde Magnussen and Christina Fiala Tømt contributed equally to this article. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments