How registered nurses at the emergency medical communication centre experience making patient assessments

Summary

Background: The number of calls to emergency medical communication centres (EMCCs) is increasing because more people with complex health challenges live at home. EMCC nurses are responsible for triaging patients and deciding on further action on the basis of one telephone call without any prior information or preparation. The caller’s ability to communicate clearly will be important in how easy it is to make these assessments. Decision support tools can be of help in triaging, but earlier research indicates that these tools are regarded as less suitable for patients with complex conditions or diffuse symptoms. A heavy responsibility rests on the EMCC nurses. Nevertheless, there is little research on how they experience being the person who must assess the situation when someone calls the centre.

Objective: To examine nurses’ experiences of assessing patients at the EMCC.

Method: The study has a qualitative research design with semi-structured individual interviews as a data collection method. The study’s empirical data were collected from EMCC nurses. The data consisted of twelve individual interviews with nurses with at least two years’ experience at the EMCC and a minimum FTE of 50 per cent. The dataset was analysed using thematic text analysis.

Results: We identified two themes that described the nurses’ experiences of assessing the patient by telephone. The theme, ‘Feeling insecure when alone with such a heavy responsibility’, describes a fear of making mistakes, while the theme ‘Professionally challenging to assess patients over the telephone’ describes how the job requires competence in many fields, and that the nurses want more support from colleagues in their assessments.

Conclusion: Nurses can find it personally demanding and professionally challenging to be alone in assessing patients at the EMCC. The findings may suggest that there is a need to facilitate better support from colleagues, cooperation, training and supervision at the communication centre.

Cite the article

Krogh R, Johansen A, Østensen E. How registered nurses at the emergency medical communication centre experience making patient assessments . Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(98177):e-98177. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.98177en

Introduction

The percentage of older people in society is growing and in turn, the number of people with complex health needs will increase (1). Local authorities have assumed several tasks that were previously assigned to hospitals. In the primary health care service, the out-of-hours emergency service (OOH service) is the first stage of the chain of emergency care. The EMCC call handlers have direct contact with patients and their families who ring the OOH service, and they have an advisory function for other actors in the primary health care service (2).

Calls to the OOH service about older patients are often characterised by the patients having general, unspecific symptoms, and it is sometimes difficult to determine their cause (3).

EMCC operators who handle emergency calls must map and assess the patient’s medical situation, decide the level of urgency, initiate action and give guidance and medical advice (2). The operators must have relevant professional medical training at a bachelor’s degree level, additional training as an operator and relevant clinical practice (4).

However, there are no guidelines on what constitutes relevant clinical practice or its duration. Normally registered nurses (RNs) act as EMCC operators and answer emergency calls. Consequently, they are the first to assess the situation (5).

EMCC operators have a heavy responsibility. Their decisions can impact patient treatment and safety as well as decide the outcome for the patient (6). A review study shows that decision-making in time-critical situations is a complex process in which many different factors must be evaluated (7).

In a short period of time, the nurse must systematically map the patient’s situation and obtain relevant information in order to make a correct and confident decision (2). The target set in the regulation on emergency medical services is that all calls should be answered within two minutes (4).

The quality of information obtained by the nurse depends on good communicative abilities (2). It also depends on the nurse being concentrated and attentive (8). Insufficient information can threaten patient safety (9). The caller’s ability to communicate is also important. Shim (10) demonstrates that health competence, attitudes and behaviour all affect the outcome.

In addition to assessing the actual situation, nurses must also reach a consensus with the caller about the right level of health care, and act as a gate-keeper for the health services (11). During the conversation, the nurse has no opportunity to make a clinical assessment based on visual cues. Consequently, the task becomes more challenging and requires the nurse to have extensive medical knowledge to be able to identify the patient’s needs. In order to safeguard patient safety, greater attention must be paid to these decision processes (12).

Several decision support tools have been developed with the aim of ensuring that patients are triaged consistently. In Norway, the most frequently used tools are the Norwegian Index for Emergency Medical Assistance, the decision support tool for telephone triage (legevaktindeks) and the Manchester triage system (2).

However, as there is no requirement that these tools should be used, the practice varies. Studies report that the decision support tool is not always seen as a support because the patient’s problem may be reduced to symptoms (13, 14). Thus it can be difficult to obtain a comprehensive view of the patient’s problems (14). In these studies, nurses related that diffuse and complex issues required most knowledge, while such conversations also took most time and led to greatest insecurity (13, 14).

Hansen and Hunskaar (15) found in their study that nurses felt it was easier to assess the most urgent cases because in less urgent cases, the patient’s symptoms could appear vague. Earlier studies have also shown that assessing diffuse symptoms correctly requires both expertise and time (11). Moreover, this entails complex decision processes (16–18) that demand both knowledge and experience.

Decision support tools may be perceived as inadequate. A Norwegian cross-sectional study by Haraldseide et al. (3) discussed older people’s contact with the OOH service. They pointed out that the decision support tool should incorporate the characteristics of geriatric illnesses better, and that the emergency nurses should have more training in interpreting older people’s symptoms (3).

The objective of the study

As mentioned above, earlier research shows that assessing patients on the telephone is a complex task, especially when the symptom profile is diffuse. At the same time, there is little research describing how EMCC nurses experience having to assess these patients and make decisions over the telephone.

Such knowledge can provide a solid foundation for quality-enhancing measures that will increase patient safety. The objective of this study, therefore, was to examine nurses’ experiences of assessing patients at the EMCC.

Method

Design

The study had an explorative, descriptive design. We used individual interviews as a data collection method, as this method is suited to performing in-depth investigations of people’s experiences (19). The article adheres to the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist for qualitative studies (20).

Recruitment and sample

The participants were recruited from two EMCCs in Eastern Norway and two in Northern Norway. Heads of section in the four local authorities identified possible informants on the basis of the inclusion criteria: nurse with at least two years’ experience at the EMCC and a minimum FTE of 50 per cent. This gave a strategic sample of participants who could provide new insights and wider understanding of the topic, illuminating the study (21).

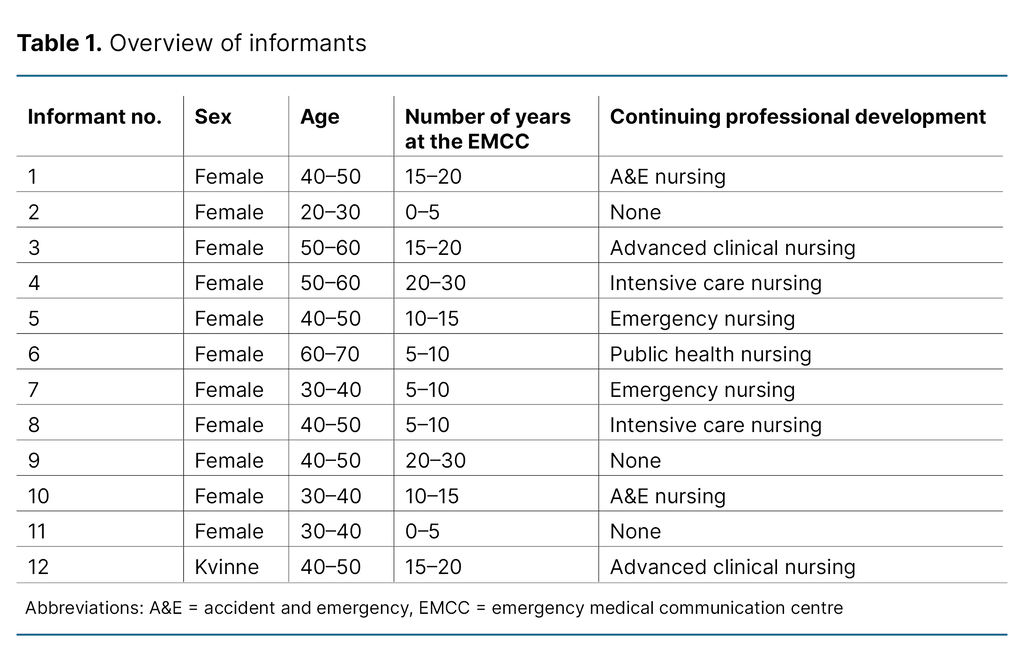

Twelve nurses were interested in participating. They received written and oral information about the study, and all of them consented to participate. The sample consisted of eleven women and one man between the ages of 24 and 70. To preserve anonymity, all the informants are registered as women in Table 1, which provides demographic information.

Data collection

The first and second authors carried out six interviews each during February 2023. Both authors are female master’s degree students with limited research experience but with broad experience from the OOH service. The interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes, and were conducted in a suitable room at the informants’ workplace. The interviewer took notes during the process. The interviews were recorded using an audio-recorder, and then transcribed.

We used a thematic interview guide in all the interviews. The guide was devised by all the authors based on the objective of the study, previous research and their own experiences. It consisted of five main topics with twenty questions.

The main topics were as follows: ‘Motivation for starting as a call handler’, ‘Induction training and positive aspects of the work’, ‘Daily work tasks’, ‘Experiences associated with triage’, ‘Experiences linked to the use of aids’, and ‘Challenges or wishes for change’.

The first author tested the interview guide in a pilot interview. We then evaluated and adjusted it in line with what worked or did not work in the interview situation. Both interviewers were keen to have a natural conversation with the informants. As a result, we could ask questions in a different order and be open to other topics that the informants regarded as important and that were relevant to the study’s research question.

In the course of the interviews, topics emerged that we wanted to explore further. These were shared with the other interviewer and included in the interview guide.

Data analysis

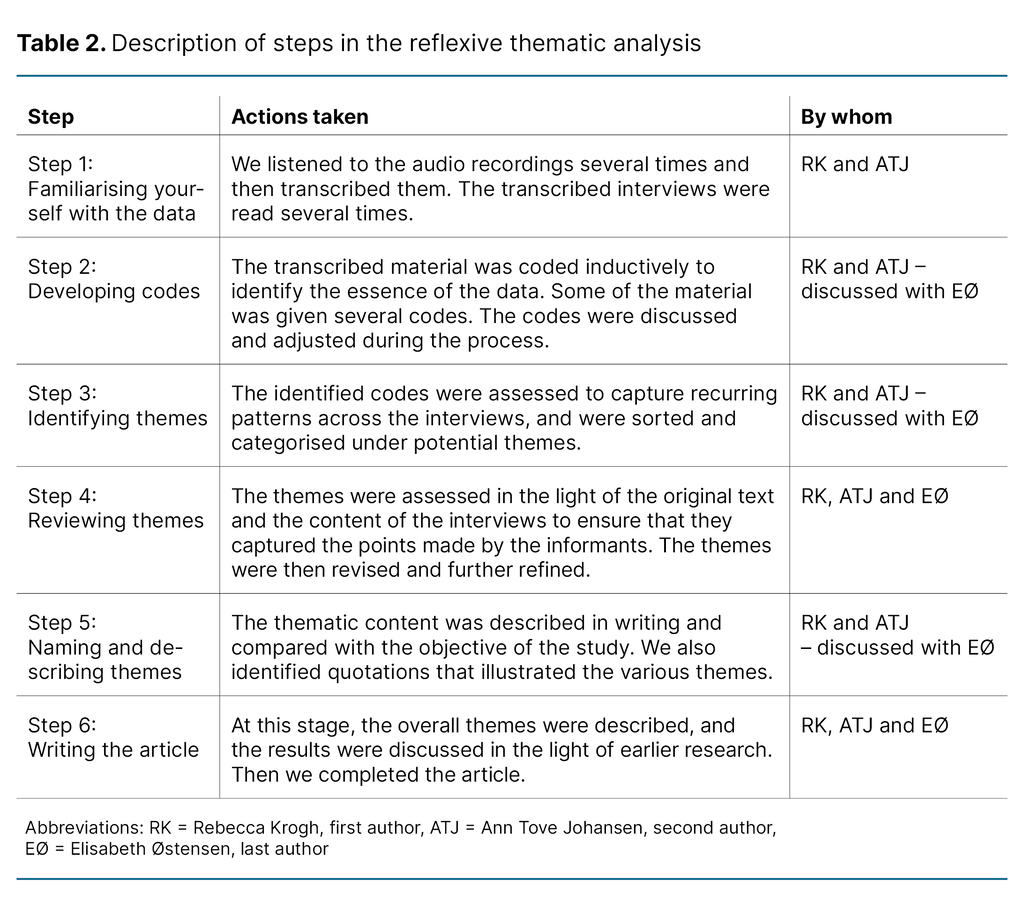

We analysed the data by using reflexive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (21). Reflexive thematic analysis entails that the researcher acknowledges their own prior understanding and reflects underway on how their own experiences may impact on the analysis (21). The analytic method consists of six steps. Table 2 shows what we did at each step of the process and which of the authors was involved.

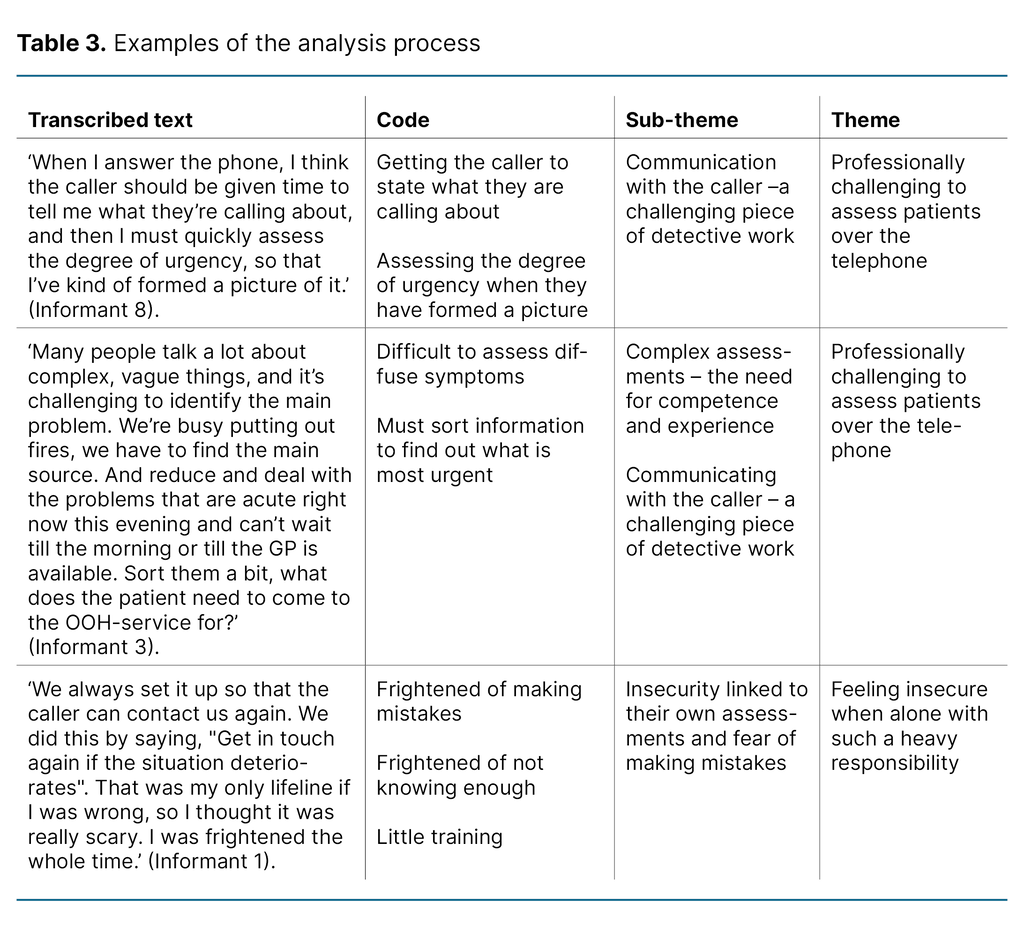

Table 3 shows examples of the analysis process – from transcribed text to theme and sub-theme.

Ethical considerations

The study was reported to the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (Sikt), reference number 925316. The heads of section at the different EMCCs gave us permission to carry out the study.

Prior to the interviews, we obtained written informed consent from the informants, and informed them that participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw from the study at any point. The informants were reminded that they should not share confidential information.

All personally identifiable information was anonymised in the transcription and audio recordings were deleted after the transcription. The collected data were stored in accordance with the guidelines of the institution responsible for the data, i.e. Lovisenberg diaconal college.

Results

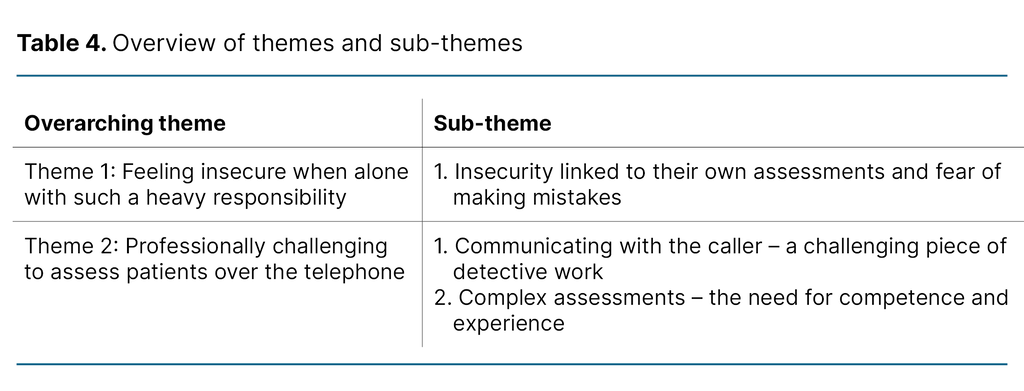

In the analysis process, we identified two overarching themes that describe the nurses’ experiences of assessing patients at the EMCC (Table 4). The themes are explored further in this chapter.

Feeling insecure when alone with such a heavy responsibility

Insecurity linked to their own assessments and fear of making mistakes

The informants in the study said that being an EMCC operator was a varied and exciting experience. However, all of them described having felt insecure when they were alone with certain assessments. Assessing questions about complex health problems felt frightening because they were afraid they had insufficient knowledge and might make mistakes.

One informant described what it had been like to be a novice operator: ‘I was always scared that I’d made a mistake, misunderstood the patient, or that I didn’t know enough about what they were calling about.’ (Informant 1)

Informants 2, 4 and 11 pointed out the need for more training and follow-up. They called into question the low requirements that were set and whether the limited call handler training they received was professionally sound: ‘I often think about the heavy responsibility we have. We’re kind of supposed to know about all kinds of patients, diagnoses and symptoms after five days training, I don’t understand how it can be lawful.’ (Informant 1)

The insecurity they felt meant that several of them chose to refer the patient for a consultation at the OOH service, so as to avoid being alone with the responsibility: ‘I always have to think about watching my back when assessing whether patients should be called in to the OOH service so as to be in the clear.’ (Informant 4)

Meanwhile several informants felt under pressure not to refer too many patients, and believed that they played an important role as gatekeepers to the emergency service.

Their work at the EMCC was also described as unpredictable. It was impossible to be prepared for the telephone conversations in advance: ‘You never know who’s going to call, you can never prepare yourself.’ (Informant 6)

The informants had to be ready to assess patients of all ages with different types of symptoms. Based on the insecurity and unpredictability of the work, half of the informants said that they wanted to have supervision and support in their clinical assessments: ‘I feel more confident when I don’t have to make the assessment on my own, when I can check with others at work. Have I made the correct decision? There should be regular supervision, in my opinion.’ (Informant 3)

Even though they could consult colleagues, there was no formal supervision, and the informants felt alone with the responsibility. ‘You’re so alone, you’re the only person to hear what they’re saying. You’re the one who has to make the decisions initially.’ (Informant 7)

All informants described a fear or concern related to making errors because of the heavy responsibility they had for the life and health of individual patients: ‘I’m not confident about having this big responsibility alone, and it’s strange that there’s no greater focus on this.’ (Informant 2)

The fear of making mistakes also applied to the personal burden they had to bear if they make a wrong assessment: ‘I think if I make a wrong assessment, it’s my personal responsibility. That’s also a burden.’ (Informant 8)

For this reason, several informants said that they needed to be exempted from responsibility: ‘It also gives a sense of security to know that I’m more in the clear if I’ve followed the triage system, because I’m aware of the huge responsibility we have.’ (Informant 1)

The informants described how this fear of making mistakes could last over time because they were never told whether their assessments were correct. As a rule, patients continued on the health service pathway without the OOH service being informed of what had happened afterwards. Therefore their ability to evaluate their own work was limited.

Professionally challenging to assess patients over the telephone

Communicating with the caller – a challenging piece of detective work

Although all the informants said it was professionally exciting to work at the EMCC, they also found it challenging: ‘I like the range and breadth you find at the EMCC with patients from 0 to 100 years old. It’s difficult but rewarding to be on the phone doing the assessments.’ (Informant 2)

All the informants described the level of urgency as the most important factor in the conversations. They found it challenging to assess patients over the telephone because they could neither see them nor examine them physically. In addition, they usually had no access to other information about the patient than what was given during the conversation.

Consequently, a difficult and important part of the job was to ask the right questions in order to form the most accurate picture of the patient: ‘You should have a lot of experience before you man the EMCC phones, it’s a great disadvantage not being able to see the patient, not being able to examine them physically or get a complete picture of the patient and their situation, so experience is absolutely essential.’ (Informant 4)

The informants described the telephone calls as a demanding piece of detective work. They explained that they usually had to sort the information they obtained from the conversations to find out what the patient needed: ‘You have twenty calls describing absolutely classical influenza symptoms, so how do you manage to pick out the one where sepsis is involved?’ It’s difficult. Terribly difficult. Beyond difficult. No one presents things in the same way.’ (Informant 8)

Several of the informants said that they had to have good clinical competence to be able to judge from the conversation whether the matter was urgent or not. As well as listening to what was said, they also listened to the voice and breathing: ‘You hear from the voice register – is the patient calm or stressed? Are they able to use full sentences? It’s difficult to put everything into words really. Because you probably get more of a general picture.’ (Informant 12)

The informants put emphasis on calming the caller to gain their trust and create a safe frame round the conversation: ‘You must create a verbal relationship to promote rich communication that builds trust. Set limits so that you get the information, quickly. Clear, authoritative and confident.’(Informant 3)

Meanwhile several informants said it could be challenging to work out what the patient needed. It might be difficult to understand each other, with different mother tongues and different ways of expressing themselves. Some conversations could also affect the informants emotionally, especially when the caller was angry or frightened. It became challenging to avoid provoking them while at the same time asking more questions.

Such conversations were challenging, and you needed to summon up your courage to deal with them: ‘You must have experience, remain calm and be brave enough to stand your ground. It’s difficult. The only way to deal with this is to have competence and knowledge. Give them solid professional reasons for your assessment.’ (Informant 10)

Complex assessments – the need for competence and experience

All the informants stated that patients with diffuse and clinically complex symptoms were especially difficult to assess. The general clinical view of the patient is the deciding factor, and it is thus important to obtain background information. The available decision support tools were a vital supplement in the assessments, acting both as a reminder and an assurance of quality.

However, some informants expressed the view that the use of the tools alone was not enough to ensure good assessments of patients with complex health problems: ‘The index alone is not enough, I have to use everything I’ve got – all my experience and training.’ (Informant 6)

The tools did not capture the complexity of the case, and the assessments therefore might be incorrect: ‘I have found the triage support tool useful, but it resulted in an awful lot of people being called in urgently to the OOH service, and we really don’t have the resources for that in the health service.’ (Informant 5)

Consequently, all the informants pointed out that good assessments of these patients depend on the operator having broad knowledge and a high degree of competence. Although it was challenging and demanding, it was also professionally rewarding to assess patients with so many different health issues.

To deal with all these calls, several informants believed that you needed personal qualities such as confidence in your own role, good local knowledge and the ability to trust your own gut feeling.

Moreover, some believed that they needed qualities such as patience, humility and openness: ‘You must have patience, you must be able to understand why you maybe get a telling-off – because that can happen. You must understand people’s reaction processes. Fear or grief can cause that kind of reaction, for example.’ (Informant 9)

Discussion

In this study, we examined nurses’ experiences of assessing patients at the EMCC, which they found challenging and made them feel insecure. The nurses said that they were frightened of making mistakes. This was linked to their fear that their understanding of the situation was inadequate, and they misinterpreted it.

Difficulties in understanding the situation may be associated with various obstacles in the communication between the caller and the nurse, such as vague descriptions of symptoms and language-related challenges (22). Earlier studies have pointed out that the fear of making mistakes can result in the overuse of limited health resources (23, 24), which this study also indicates.

There is a growing need for health services. Meanwhile, there is already a shortage of resources (11), and it is therefore important to avoid unnecessary use of the health services. By implementing measures to increase the EMCC nurses’ confidence, it may be possible to reduce unnecessary use of the OOH service.

A 2023 study (25) points out that over-triaging may affect the workflow at the OOH service in a negative way. It may result in more concurrency conflicts and challenges in prioritising between calls with the same level of urgency, which in turn can be stressful for the health personnel (25).

The danger of under-triaging is that the patient does not receive the necessary health care at the right time. If necessary treatment is delayed, this may have fatal consequences (26). This risk becomes particularly evident when communication is by telephone.

Sole responsibility led to insecurity

Our study also found that nurses were insecure when it came to having sole responsibility for asking the necessary questions, identifying health needs and making correct assessments of the patient. This responsibility is seen as a significant challenge. The informants described challenging conversations, uncertainty about whether they had understood the caller and assessed the situation correctly, and well as time pressure at the EMCC.

This can be compared with a Norwegian study that investigated how new doctors experienced the clinical assessment of patients. The study described how newly qualified doctors in particular felt discomfort and uncertainty about whether they had made the correct assessments, a feeling echoed by a number of experienced doctors. This feeling of insecurity affected them both physically and mentally (27).

Another study exploring nurses’ experiences of dealing with challenging telephone conversations at the EMCC found that such conversations could create anxiety and emotional reactions in nurses even long after the conversation ended (22).

Support from colleagues and evaluation are important after challenging conversations

A Swedish study from the emergency medical service (24) emphasises that emotional support is important after challenging conversations. The informants in our study mentioned the importance of support from colleagues and expressed a wish for closer cooperation and supervision.

Earlier studies (22, 23) support the finding that the individual can derive benefit from reflection, discussions and feedback from colleagues after challenging conversations. Receiving confirmation that your thinking is correct can make nurses feel more confident in their work (28).

The informants in our study would also like their call handing to be evaluated so that they could feel more confident about their own assessments. Such confirmation could help them process and learn from the situation they have experienced (23).

Due to strict personal data legislation in Norway, it is difficult for the OOH service to find out about patient outcomes. Consequently, we must find other ways of giving the nurses feedback, for example through the supervision of their colleagues.

Different tools and measures help the nurses

A Norwegian study examining the quality of EMCC triage assessments pointed out that it would be a learning experience if the same nurse that took the call, was to meet the patient on arrival at the OOH service centre (15). This quality improvement measure could be trialled at several OOH services.

The nurses in this study said it was difficult to assess patients’ health needs when they were unable to see them. Earlier research has shown that nurses form a mental picture of the patient and that they use this picture as well as their clinical knowledge and decision support tools to map the situation during the telephone conversation (29).

We also found that the nurses felt it was challenging to assess diffuse symptoms. Moreover, the support tools did not always provide an answer since they require a clear symptom and are not adapted to complex health conditions.

The strengths and weaknesses of the study

The first and second authors have experience as EMCC nurses. Research in one’s own field can be challenging as it easy to be blind to experiences other than one’s own. Consequently, we made active choices during the entire process from the formulation of the questions in the interview guide to the selection of themes and codes. We acknowledge that our experience and prior knowledge of the EMCC directly impacts on the data when we use this method (30).

The researchers’ prior understanding will affect the questions and their interpretation. The interviews were carried out by two different people with different attitudes and prior understandings. This may produce dissimilar results. We have taken active measures to avoid excessive bias, for example by sharing our perceptions after each interview.

The last author, who had no experience from the EMCC, asked critical questions and participated actively in the planning of the study, the analysis process and the presentation of the results.

Another weakness may be that the heads of section identified potential informants for the study. They may have chosen informants who they felt were particularly interested or who would present their workplace in the best possible manner. Meanwhile, the results show that most participants also pointed out work-related challenges. This indicates that the sample did not influence the results of the study in any particular direction.

Conclusion

The findings in this study show that nurse may find it professionally challenging and personally demanding to make assessments at the EMCC. The informants had a feeling of insecurity at work. They were frightened of making mistakes and shouldering the responsibility alone, and they described a need for structured training and supervision.

The study sheds light on the human aspects of working at the EMCC. The findings may indicate that nurses have a need for support and cooperation in relation to the assessments they make at the EMCC. This indicates a need to facilitate support and supervision from colleagues to enable them to handle challenging conversations better and evaluate assessments, giving them more confidence in their own assessments.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all the twelve nurses who were willing to share their unique experiences of working at an emergency medical communication centre. The first and second authors also wish to thank Elisabeth Østensen for her patient, thoughtful supervision of two practitioners on their academic journey. We couldn’t have done it without you!

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments