Women’s experiences with postpartum urinary retention – a qualitative study

Summary

Background: Postpartum urinary retention (PUR) affects between 0.18 and 14.6% of all postpartum women globally. To prevent sequelae to the bladder and urinary tract after childbirth, it is important to ensure effective bladder emptying. This is done by regularly emptying the bladder using a single-use catheter. The procedure is usually carried out by healthcare personnel in a hospital, after which the women are taught how to do it themselves. However, there was a lack of evidence-based knowledge on postpartum women’s experiences of being trained to use a catheter to empty their bladder and actually using the catheter.

Objective: To explore women’s experiences with PUR. We also wanted to examine the challenges they face with self-catheterisation whilst caring for their newborn child.

Method: The study has a qualitative exploratory design. We conducted semi-structured individual in-depth interviews with women who had experienced urinary retention for one to three weeks after childbirth. The data underwent a thematic analysis.

Results: The women were not prepared for the possibility of PUR. They experienced inconsistent and inadequate follow-up of their condition on the maternity ward. The training in self-catheterisation made the women feel that the care they received and the facilities at the maternity ward were inadequate. PUR also affected their lives after returning home. Returning home with PUR whilst having to care for their infant was challenging. However, the women were solution-oriented and coped well with daily life with PUR and their newborn child.

Conclusion: Experiencing PUR was contrary to the women’s expectations for the postpartum period. They found there to be a lack of information on PUR and wanted healthcare personnel to have a clearer and more consistent follow-up strategy for the condition. They also wanted more involvement in their care. The facilities associated with training at the hospital were not considered optimal. The condition and the practical challenges it entailed had implications for their daily life even after returning home, but they found effective ways to cope.

Cite the article

Aga M, Beisland E. Women’s experiences with postpartum urinary retention – a qualitative study. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(95719):e-95719. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.95719en

Introduction

The incidence of postpartum urinary retention (PUR) ranges from 0.18 to 14.6%, and it is defined as the inability to urinate spontaneously within six hours of childbirth or after catheter removal following a caesarean section (1, 2).

Women who receive an epidural when in labour are known to be at the highest risk of developing PUR. Prolonged labour, episiotomy, oedema, haematomas and perineal tears are also known risk factors that can lead to bladder-emptying problems after childbirth. If PUR is not detected and treated in time, repeated overstretching of the bladder can lead to persistent emptying issues and potential sequelae to the bladder and urinary tract (1, 3).

Bladder scanning and regular catheterisation are essential for the diagnosis and treatment of PUR. To ensure effective bladder emptying, the bladder should be emptied regularly using a single-use catheter. The method is called intermittent catheterisation (IC) (1, 2).

Research shows that patients who have to carry out self-catheterisation experience various problems (4). The loss of normal bladder function can trigger emotional reactions in patients in the form of grief (5).

A study of men and women who had to learn self-catheterisation for a variety of reasons identified psychological issues, physical problems and interaction difficulties. However, nurses who were good communicators helped ease the learning experience. A friendly, relaxed approach alleviated patients’ embarrassment and anxiety, thus facilitating cooperation and the exchange of information (6).

This was one of only a few studies that focus on patient experiences with IC and the problems and challenges it entails for women in their daily lives (5). We are not aware of any previous studies on women’s experiences with self-catheterisation in the early postpartum period. In a study of 222 postpartum women, it was found that more physical symptoms were associated with more breastfeeding problems and lower breastfeeding self-efficacy (7). However, the study did not investigate PUR specifically.

The e-manuals of Oslo University Hospital and Bergen Hospital Trust state that it is important to document that normal urination has resumed within three hours of childbirth. This is particularly important in first-time mothers as they have a higher risk of urinary retention. A bladder scanner should be used to check for residual urine. If the result is ambiguous, clean intermittent catheterisation (CIC) should be performed. In cases of persistent urination problems and large volumes of residual urine, a plan should be drawn up to monitor and ensure bladder emptying over the next few days. The midwife should consider consulting a urotherapist, urogynaecologist or urologist for further follow-up (8, 9).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to explore women’s experiences with PUR. Increasing knowledge on this can help women feel better cared for in the maternity ward and improve follow-up in the postpartum period.

Method

The study employed a qualitative method with an exploratory design (10) and was conducted according to the COREQ checklist (11). Data were collected in individual semi-structured interviews (12).

Sample and recruitment

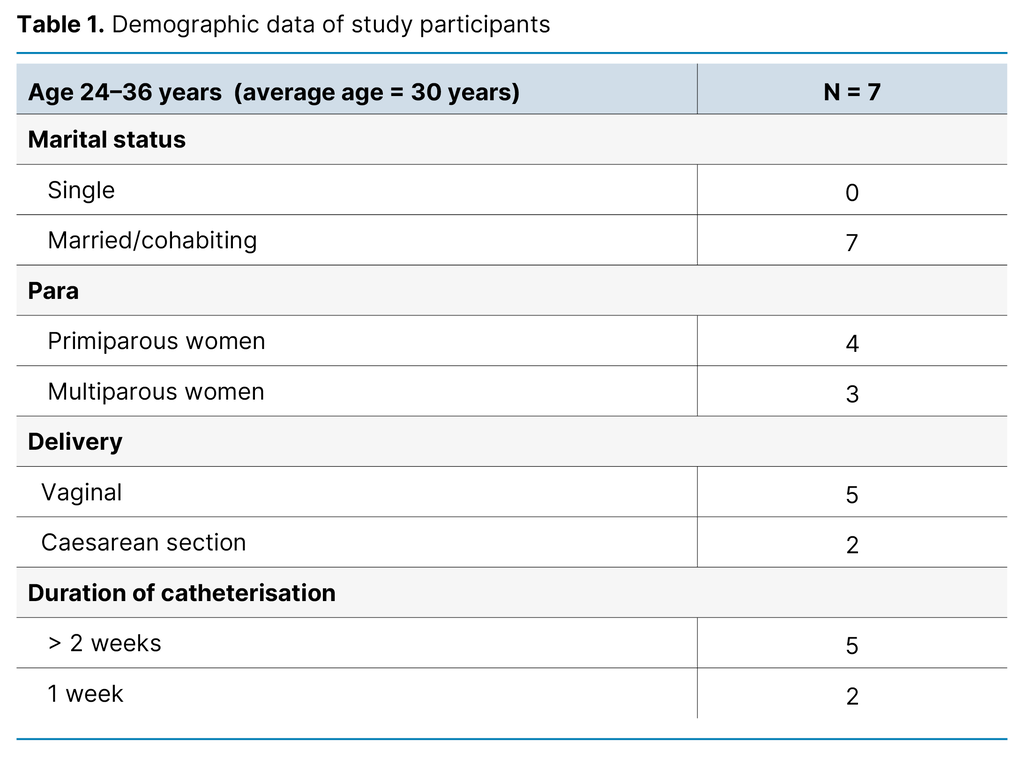

We wanted to recruit a wide variety of informants who could shed light on the research question from different perspectives. We recruited informants on an ongoing basis to obtain a representative sample (13). The participants consisted of seven women who had experienced PUR and had received training in self-catheterisation before discharge from the maternity ward (see Table 1). All participants had carried out self-catheterisation for one to three weeks after childbirth.

The inclusion criteria were: age 18 or over, capacity to consent and ability to communicate in Norwegian or English. They had to have performed self-catheterisation for more than one week after childbirth. The participants were recruited by a nurse during outpatient check-ups at a large hospital in Norway, and were not therefore known to the interviewer. All the women who were approached, agreed to participate in the study.

Data collection and analysis

The data were collected between March 2022 and March 2023. We devised a semi-structured interview guide according to the guidelines of Kallio et al. (14). The first interview was conducted as a pilot to test the interview guide.

The first author conducted the semi-structured in-depth interviews, which lasted 45–60 minutes. Four women were interviewed at the hospital and three were interviewed at home. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim as soon as possible afterwards (12).

We applied Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis method (15, 16). In the first phase, both authors thoroughly read all the interview transcripts multiple times to familiarise themselves with the data material. In phase two, we discussed and identified initial codes, and in the third phase, we grouped the codes and identified preliminary sub-themes and themes.

In phase four, codes, sub-themes and themes were discussed and readjusted in light of the context. In phase five, we established final themes and placed them in a matrix. In the final phase, we prepared a final report with illustrative quotes to support the themes.

Ethical considerations

The Norwegian Centre for Research Data, now called Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, and the data protection officer at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL) were notified of the project (reference number 992502). We also obtained written permission from the clinical director at the relevant hospital.

Patients received written and oral information about the study from the nurse at the outpatient clinic before being asked to participate. The women signed an informed consent form and were told they could withdraw from the study if they wished. We stored transcripts and personal details such as names and phone numbers in separate files on HVL’s research server.

Results

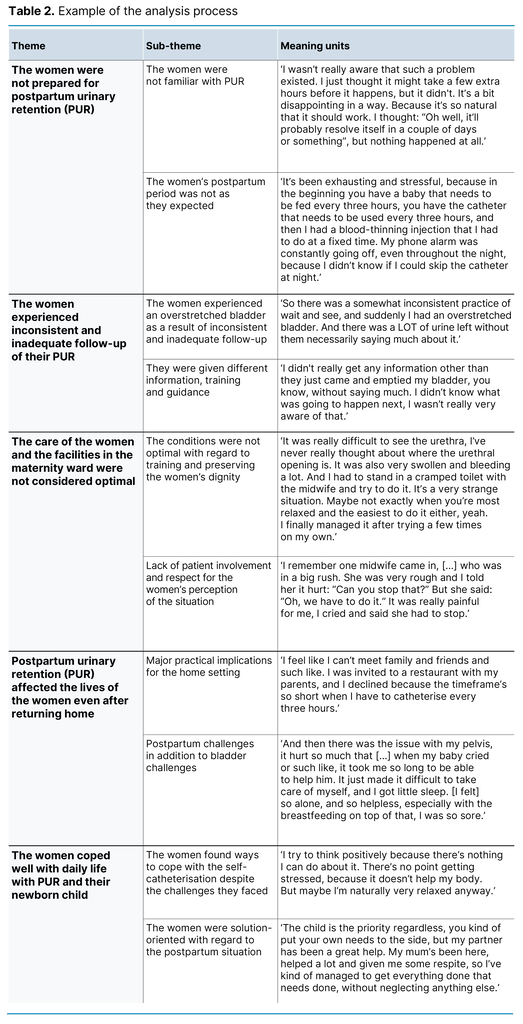

The data analysis led us to the following five themes, based on codes and identified sub-themes: 1) The women were not prepared for postpartum urinary retention (PUR), 2) The women experienced inconsistent and inadequate follow-up of their PUR, 3) The care of the women and the facilities in the maternity ward were not considered optimal, 4) Postpartum urinary retention (PUR) affected the lives of the women even after returning home and 5) The women coped well with daily life with PUR and their newborn child (Table 2).

The women were not prepared for postpartum urinary retention (PUR)

The women were not familiar with PUR and seemed surprised that they could experience bladder problems after childbirth. One of the informants, Camilla, explained it as follows:

‘I was so surprised that I hadn’t heard about this before, you only hear about those who leak a bit, you know, but nothing about those who can’t pee [laughs]. I feel that I prepared myself well before giving birth, listened to a lot of podcasts. I feel like I’m up to date on what’s normal after childbirth, but I’ve never heard about this [PUR]. I don’t think I knew that disposable catheters even existed.’

The postpartum period was different from what the women had hoped for. Having to carry out IC after childbirth led to various emotional reactions. They expressed stress reactions and emotional responses. Maria described this as follows:

‘It was like a cold shiver down my spine every time I thought about it [PUR]. No, now I have to do it again, I felt a bit stressed, almost started sweating. Imagine, now I have to go into that cramped bathroom and go through it all again there. I never knew, because I didn’t feel that I had to pee, I didn’t feel how much was in my bladder either.’

The women experienced inconsistent and inadequate follow-up of their PUR

Most of the women expressed frustration that the healthcare personnel had different approaches to the follow-up of PUR. Liliana recounted the following:

‘A midwife came and said: “No, we have to empty more often, we have to do this every two hours because we can see there’s a lot left in the bladder.” Then a new midwife came on shift who said: “We can wait another hour!” But when I had waited that hour/hour and a half, my bladder had stretched! It was a bit frustrating!’

The women found it frustrating when they were given different information, training and guidance from the healthcare personnel at the hospital. Sofia described it as follows:

‘I was told by a nurse in the outpatient clinic that there shouldn’t be any resistance when inserting the catheter. [When] I tried again in the maternity ward, I couldn’t do it. Then another nurse helped me by pushing past where there was resistance. There was a bit of discomfort, but I didn’t think much of it at the time. [When] I tried at home, I started bleeding afterwards, so I realised then something was wrong! Then I was scared to death!’

The care of the women and the facilities in the maternity ward were not considered optimal

The women received training in IC in a cramped toilet together with the midwife. Several found it uncomfortable to have healthcare personnel up so close and personal. Some also found it uncomfortable looking at their genital area during the IC training. Maria recounted the following:

‘I’m given a mirror and have to look at myself down below. It’s bleeding, and I’m supposed to get help from someone else, and they then look at it. I feel really small, in a way.’

The women felt like a nuisance to the other women they shared a room with when they had PUR, particularly when there was a lot of focus on follow-up. They also missed having their partner present to help with their infant. The women found that the healthcare personnel’s experience varied. Kira said the following:

‘It wasn’t a good feeling to be IC’d in the room! No one did it the same way. Some are very careful, while others are not. I remember one midwife came in who was in a big rush. She was very rough and I told her it hurt: “Can you stop that?” But she said: “Oh, we have to do it.” It was really painful for me, I cried and said she had to stop.’

Postpartum urinary retention (PUR) affected the lives of the women even after returning home

The women experienced some stress in obtaining self-catheterisation equipment at the pharmacy, and some considered the equipment expensive. They also had technical challenges with IC, both at home and elsewhere, and were worried about getting an infection. They found the IC procedure time-consuming and felt stressed about having to live by the clock. Several therefore isolated themselves at home. Sofia expressed the following:

‘I feel tied to my home, because everything has to happen within a certain timeframe. When we go out, I end up being late. I feel like I can’t meet family and friends and such like. I was invited to a restaurant with my parents, and I declined because the timeframe’s so short when I have to catheterise every three hours.’

The women deprioritised their own basic needs and struggled with other postpartum challenges, such as pain, swelling and bleeding in the genital area. They also experienced hormonal and emotional fluctuations. Kira recounted the following:

‘I noticed that I was losing weight. I talked to my doctor about feeling like I was disappearing. I felt like I was about to be hit with postpartum depression. I felt like I wasn’t myself, I was someone else.’

The women coped well with daily life with PUR and their newborn child

Despite challenges in following up and carrying out IC, the women coped well with their new daily life at home with their newborn child. PUR and all it entailed never took precedence over their infant. Theresa commented as follows:

‘It’s like the baby’s needs come first, so it’s a bit non-stop. Suddenly you have to breastfeed, or there’s something else you have to give priority to with your infant. So you stand there thinking: “Yeah, I need to get to the toilet!” So I just have to put her down on the changing table, have her there next to me, and do what I need to do while she’s crying. That’s just how it has to be, I just have to prioritise.’

The women tried to stay positive about the situation in order to cope as best they could. Helene commented as follows:

‘I feel a bit like a three-year-old being toilet trained [laughs]. You just have to look at things with a bit of humour, it doesn’t help to be negative.’

Discussion

The women interviewed had little knowledge of PUR, and several had never seen a catheter. This finding is consistent with a study that examined various patients’ experiences with self-catheterisation (6), where it emerged that the patients wished they had received more information about this from healthcare personnel. In another study, the patients were shocked by bladder dysfunction and unaware of self-catheterisation (4).

Section 3-2 of the Norwegian Patients’ and Service Users’ Rights Act (17) sets out patients’ and service users’ right to information and states that ‘the patient shall have the information that is necessary to obtain an insight into his or her health condition and the content of the health care. The patient shall also be informed of possible risks and side effects’. This had evidently not been adequately addressed among the women interviewed.

The women were clear that the postpartum period was not as expected as a result of PUR. A study of postpartum women in general found that the women were not well prepared for the early postpartum period at home. They lacked information about the postpartum period and what was normal for themselves and their infant (18). We live in a digitised world, with options to distribute information through all kinds of digital platforms, such as websites and podcasts. Health trusts and healthcare personnel should seize the opportunity to inform patients via such platforms.

Follow-up was inconsistent and inadequate

The women felt that the follow-up of their PUR was neither consistent nor adequate. Several felt that they were not listened to and suffered from bladder overstretching after childbirth. Previous studies have shown that even a single instance of overstretching can lead to complications in the form of urinary retention and sequelae to the bladder (19).

In 2014, a review was conducted of urinary retention cases in Norwegian hospitals, which revealed that most cases occurred in maternity and surgical wards. The maternity wards reported that bladder overstretching could, in some cases, be due to hospital capacity challenges, insufficient documentation and lack of follow-up of diuresis, i.e. the amount of urine produced over a certain period of time. On this basis, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health posits that many cases of urinary retention could possibly have been prevented if enough healthcare personnel had been on duty (19).

Few studies have examined women’s experiences with IC (5). Nevertheless, nurses’ communication skills are considered crucial for ensuring that patients do not feel embarrassed or stressed in their cooperation and exchange of information with nurses (6).

There should therefore be a sufficient number of midwives or nurses on duty in maternity wards to ensure optimal communication and information. Nurses must assess the individual needs of each woman and follow up with a plan for bladder emptying in accordance with current guidelines (8, 9).

Learning self-catheterisation was challenging

Several informants reported feeling shame when they had to learn how to carry out IC after childbirth, and that the facilities in the maternity ward were not optimal. They found it uncomfortable having to be trained in a small, cramped communal bathroom. Several informants were not familiar with their own anatomy and the location of the urethra. This finding aligns with the results of a study in which women said they did not know their own body well enough or where the urethra was (4).

Several of the women also felt that no one was interested in their perception of their bladder situation and expressed a lack of patient involvement. The perceived disregard for their concerns and the staff’s failure to take their perspective on bladder function into account when assessing the need for catheterisation may suggest staffing shortages, resulting in time constraints and communication challenges.

The women experienced a high level of stress when they returned home in relation to obtaining equipment and having to adhere to a strict self-catheterisation schedule. They faced technical challenges with the IC procedure due to bleeding, swelling and pain in the genital area. These factors combined led to several of the women isolating themselves at home. Logan’s study of other patient groups who had to carry out self-catheterisation also found that catheterisation leads to home isolation (6).

The study by Puritz et al. (7) showed that the more physical symptoms and discomfort postpartum women experienced, the greater their breastfeeding problems and the lower their self-efficacy. Previous studies have also demonstrated that calmness and good care during the postpartum period can protect against postpartum depression. Self-efficacy and good social support can alleviate anxiety and stress (18).

Healthcare personnel who are involved in IC training after childbirth should therefore provide women with individually tailored information and allocate sufficient time for training. They should strive to facilitate the best possible care for the woman and her infant both at the hospital and during the transfer to the home setting. The patient’s family should also be informed and involved. This overall approach would benefit postpartum women’s breastfeeding and general well-being (7).

Despite challenges with PUR, the women coped well with their daily life and newborn child after returning home. They put their own needs aside and prioritised the care of their infant during a vulnerable time with major hormonal fluctuations and bodily changes. IC at fixed times was a high priority, and the women were solution-oriented with regard to the postpartum situation. Active coping and humour were two of the coping strategies used by the women (20, 21).

Strengths and limitations of the study

The fact that the study was conducted according to the COREQ criteria (11) is considered a strength. We produced a rich dataset, despite only seven women being interviewed. The women’s age, number of previous births and experiences varied. The aim of the analysis was to identify the themes that emerged in the data material, thereby improving the understanding of the women’s experiences with PUR.

The researchers were mindful of their own preunderstanding throughout the research process and did not allow this to influence the analysis. We did not find any previous research reporting on women’s perspectives on their PUR. The findings were therefore discussed in light of results from other patient groups’ experiences with self-catheterisation. This could be considered a weakness of the discussion, but the comparison was nevertheless interesting.

Conclusion

Contracting PUR was contrary to the women’s expectations for the postpartum period. They were unprepared for PUR and would have liked more information about the condition. They wanted more consistent follow-up of the condition and more involvement. They did not consider the care and facilities in the maternity ward to be optimal. The urinary retention affected the women’s daily life after returning home, but they found effective ways to cope with the condition.

The findings from this study have clinical implications for healthcare personnel in maternity wards, indicating a need for more information about PUR for new mothers. It also appears that resources need to be strengthened in the form of healthcare personnel to provide information, training and consistent follow-up of PUR. More research is needed on this topic from the perspective of postpartum women in order to improve the knowledge base in the field.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments