The transition from intensive care nursing student to competent intensive care nurse – intensive care nurses’ experiences

Summary

Background: The shortage of intensive care nurses in Norway has led to the creation of more student places. Intensive care nurses must be able to integrate advanced theoretical knowledge with practical and interpersonal skills in order to care for acutely and critically ill patients and their families. Little is known about new graduate intensive care nurses’ experiences of the transition from intensive care nursing student to qualified intensive care nurse.

Objective: To gain an understanding of intensive care nurses’ experiences of the transition from intensive care nursing student to competent intensive care nurse in intensive care units (ICUs) in Norway.

Method: The study is qualitative with a hermeneutic approach. We conducted three focus group interviews with 12 intensive care nurses in February 2022. Two of the focus group interviews were held at level 1 ICUs in local hospitals and one was held at a centralised hospital with level 2B ICU. Nine of the participants had worked in an ICU before specialising in intensive care. The hermeneutic analysis model by Fleming et al. was used to analyse the data, in addition to Kvale and Brinkmann’s step-by-step analysis process, where meaning coding and meaning interpretation are central.

Results: Three main themes emerged: 1) High-level competence requirement, 2) Substantial responsibility and 3) Becoming a competent intensive care nurse takes time and requires professional support and teamwork. New graduate intensive care nurses found the responsibility and competence requirements to be greater than expected. Participants experienced differing competence requirements at local and centralised hospitals. Being assigned more responsibility by practice supervisors with considerable experience in intensive care nursing during clinical placements made the transition easier. New graduate intensive care nurses need professional support from more experienced intensive care nurses.

Conclusion: Experience from the intensive care field before specialising in intensive care nursing aids the transition to competent intensive care nurse. Organisational constraints such as staffing challenges and insufficient intensive care resources hinder the transition of new graduate intensive care nurses. It takes time to become a competent intensive care nurse, and they must be given the time they need.

Cite the article

Jacques M, Willumsen H, Mæhre K. The transition from intensive care nursing student to competent intensive care nurse – intensive care nurses’ experiences. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(95528):e-95528. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.95528en

Introduction

Intensive care nurses work with acutely and critically ill patients who need continuous treatment, monitoring and care. They attend to patients whose vital functions need to be restored after anaesthesia, surgery, trauma or acute exacerbation of a chronic illness (1).

According to the Regulations on National Guidelines for Intensive Care Nursing Education (1), hereafter referred to as ‘the Regulations’, candidates should, upon completion of their education, possess action competence and thus be competent practitioners. This competence entails the capability to make independent clinical judgements and decisions, and to prioritise tasks, allowing for early detection of any deterioration in the patient’s condition and implementation of appropriate interventions (1).

Within 17 years, approximately 40% of intensive care nurses in hospitals in Norway will have reached retirement age (2). Three out of four intensive care units (ICUs) in Norway currently have vacancies for intensive care nurses (3). The Health Personnel Commission (4) believes that the challenge of recruiting intensive care nurses in Norwegian hospitals makes it difficult to maintain Norway’s high standard of health services. The shortage of intensive care nurses has led to the creation of more student places in intensive care nursing education in Norway (5).

Intensive care nursing students in Norway now only need 90 ECTS credits to complete their studies (1). Students who complete 120 ECTS credits are awarded a master’s degree in intensive care nursing (1). The admission criteria for the intensive care nursing programme have included a requirement for two years of nursing experience after completing a bachelor’s degree in nursing (6). Several educational institutions abolished this requirement in 2023 (4).

Background

Intensive care nursing students in Norway are most satisfied with the clinical placements in the study programme for intensive care nursing, despite many experiencing varying quality among practice supervisors (7). Practice supervisors find that supervision is resource-intensive and a major responsibility (8).

International studies focus on new graduate nurses’ transition to practising nurse in an ICU. Studies have shown that insufficient investment in relevant education and training programmes has a negative impact on new nurses in an ICU, leading to what is termed ‘transition shock’ (9–13). One consequence of this is an increased staff turnover (9).

A phased introduction to working in an ICU (14), good preceptorship in the beginner phase (9, 10, 12) and practical experience over time contribute to a more manageable transition process and increased confidence in the role of intensive care nurse (11, 13). We did not find any research on the experiences of new graduate intensive care nurses in the transition from intensive care nursing student to practising intensive care nurse.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain an understanding of intensive care nurses’ experiences of the transition from intensive care nursing student to competent intensive care nurse in ICUs in Norway. The background for the study was the need to recruit and retain intensive care nurses in an ICU.

Probing research questions:

- What are intensive care nurses’ experiences of being a new graduate intensive care nurse?

- What promotes or hinders a smooth transition from intensive care nursing student to practising intensive care nurse?

The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research (15) defines ‘competence’ as the ability to solve tasks and overcome challenges in specific situations. The concept of competence comprises of the sum of knowledge, skills and attitudes, and how these are applied in combination (15).

The term ‘competent intensive care nurse’ is inspired by Benner’s (16) five stages of proficiency: novice, advanced beginner, competent practitioner, proficient practitioner and expert. According to Benner (17), at least two to three years of work experience is needed to become a competent practitioner.

Method

The study has a qualitative and exploratory design, which is suitable for subjective experiences and under-researched topics (17, 18). Our data collection method was focus group interviews, which stimulate reflection and discussion among participants (17, 19).

Recruitment and sample

The sample is strategic, which involves targeted recruitment of participants who can shed light on the research problem (19). The first and second authors first contacted department heads at various ICUs in Norway. The department heads suggested relevant participants based on the following inclusion criteria: one to three years’ work experience as an intensive care nurse in an ICU in Norway and a Norwegian education in intensive care nursing. The authors subsequently contacted relevant participants. We did not include anyone from our own workplace. All enquiries were dealt with via email and telephone.

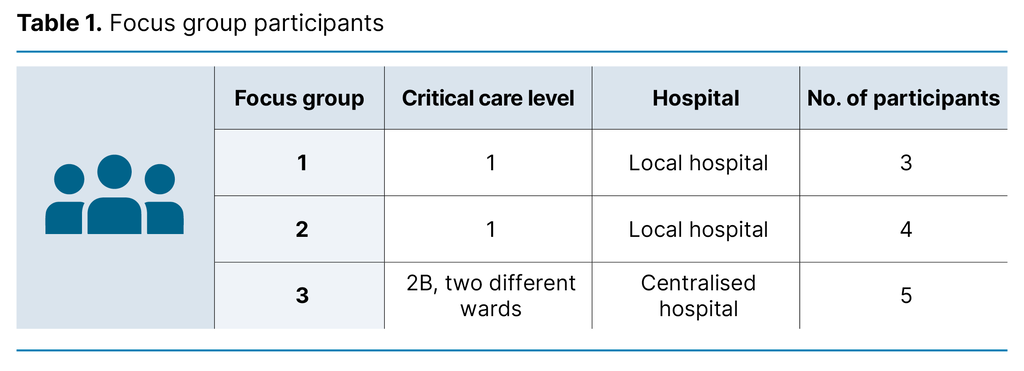

We recruited 13 intensive care nurses from two different regional health authorities in Norway to take part in three focus group interviews. One participant cancelled for personal reasons on the day of the focus group interview. Four men and eight women participated in the study. Each focus group interview consisted of three to five participants (Table 1).

Nine of the participants had worked in an ICU for a period of a few months to ten years before specialising in intensive care nursing. For anonymisation purposes, we do not disclose the individual participants’ length of service. In Norway, ICUs are classified in four levels (20). The higher the level, the more complex the treatment modalities and the requirement for round-the-clock staffing by specialist intensive care personnel (Table 2). The participants in the study worked in level 1 and level 2B ICUs.

Data collection

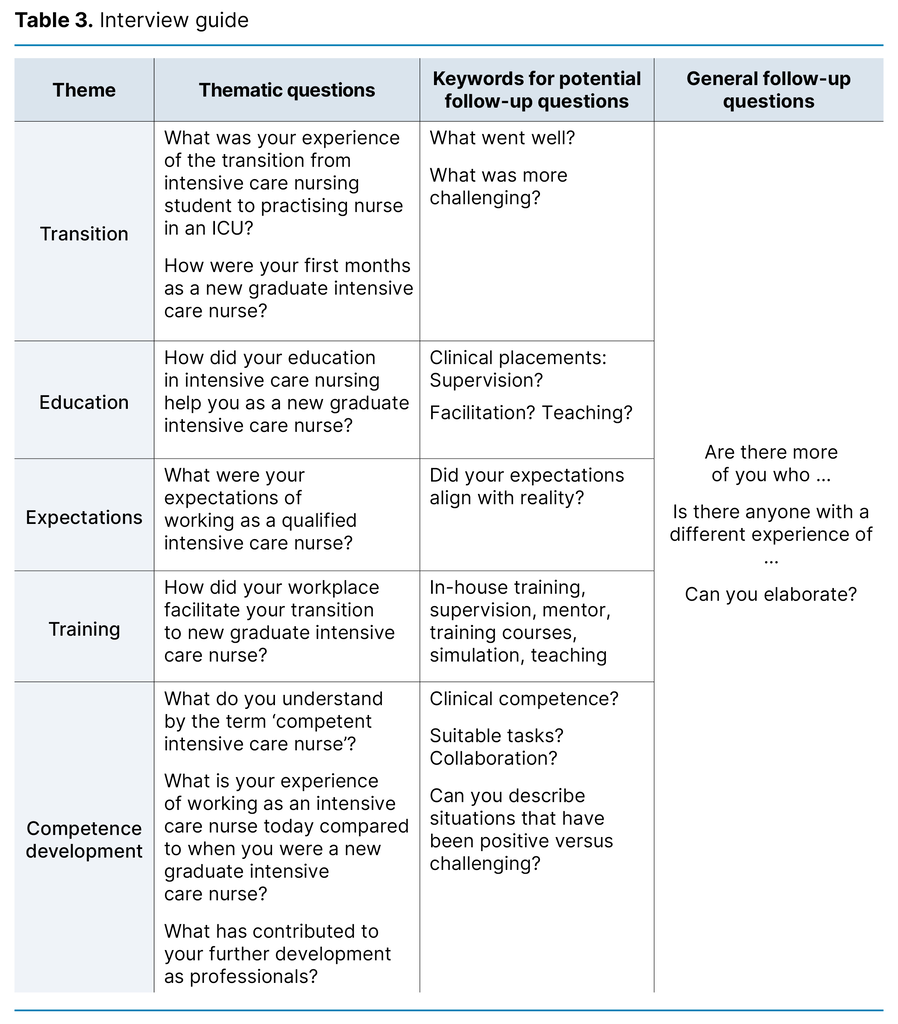

Before collecting the data, we devised a semi-structured interview guide inspired by Krueger and Casey’s (21) advice on conducting focus group interviews. We developed the content of the interview guide based on previous research and knowledge gaps. The interview guide was piloted in an interview with new graduate intensive care nurses from the same cohort as the first and second authors.

After the pilot interview, the first and second authors discussed the content of the interview guide with the project supervisor/last author. The interview questions were subsequently refined, and additional follow-up questions were added (Tabell 3).

The project supervisor served as the moderator in the first focus group interview. In the next two interviews, the first and second authors alternated between the roles of moderator and secretary. The focus group interviews lasted between 60 and 70 minutes and were held at the hospitals where the participants worked. Two audio recorders were used.

Each focus group interview began with us presenting the study’s objective and research questions, and asking if the participants had any questions about the written information and informed consent. The secretary took field notes and provided a brief summary after each interview. The first and second authors transcribed the audio recording immediately after the interviews.

Analysis

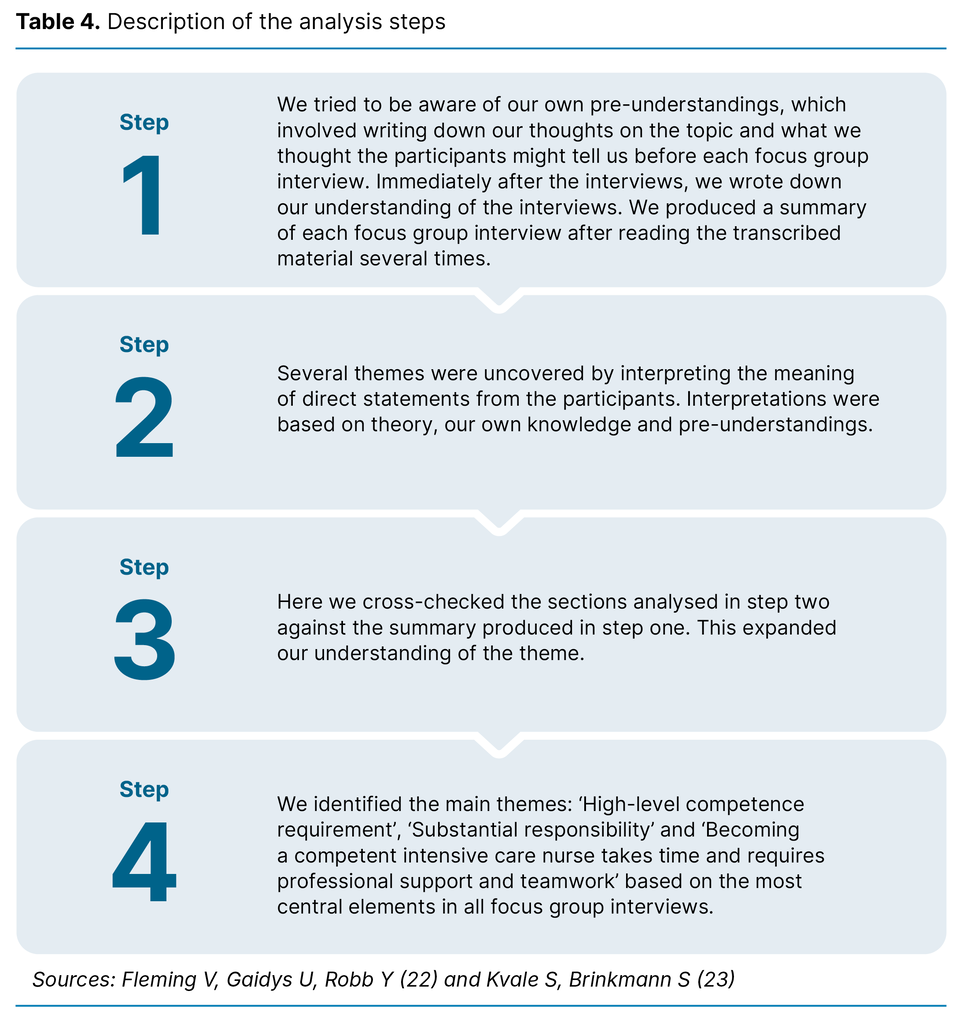

In our analysis, we used the hermeneutic analysis model of Fleming et al. (22), as well as Kvale and Brinkmann’s (23) step-by-step analysis process, where meaning coding and meaning interpretation are key concepts. Fleming et al.’s (22) analysis model is inspired by Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics and hermeneutic circle, where the whole must be understood in connection with the parts, and the parts in relation to the whole.

In hermeneutics, the work involved in reading and analysing textual material entails constantly challenging the researcher’s understanding. Fleming et al.’s analysis model (22) consists of four steps: Step 1) Find the whole meaning of the text and identify own pre-understandings, Step 2) Identify themes by looking at the parts of the text, Step 3) Gain more understanding by looking at the parts in relation to the whole, and Step 4) Identify themes (Table 4).

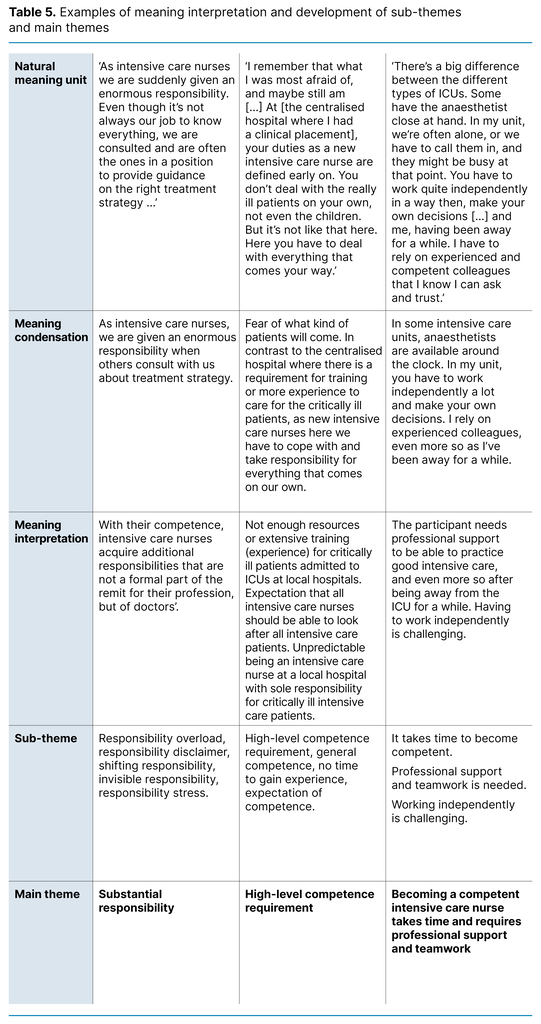

The first and second authors first conducted a manual analysis in Excel. The analysis, main themes and sub-themes were then discussed with the project supervisor. Examples of the development of themes are illustrated in Table 5.

The participants were sent the results of the focus group interviews. After the focus group interviews, we encouraged the participants to provide feedback on the results, but none of them did.

Ethical considerations

The Norwegian Centre for Research Data, now called Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number 747094), was notified of the study. Participation was voluntary in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (24). The participants gave their consent to participation either electronically or in writing and were informed that they could withdraw their consent during the study, which none of them did.

All interviews were stored in an encrypted file and deleted from the audio recorders’ memory cards. The data were stored and processed in accordance with legislation and regulations on the handling of personally identifiable information (25).

Results

Three main themes and associated sub-themes emerged in the analysis:

- High-level competence requirement

- Linking theory to clinical practice aids knowledge development

- Differing competence requirements at local and centralised hospitals

- Substantial responsibility

- From piecemeal and shared responsibility to sole responsibility

- Dealing with unexpected situations – responsibility stress

- Becoming a competent intensive care nurse takes time and requires professional support and teamwork

- The transition from intensive care nursing student to new graduate intensive care nurse is considered challenging

High-level competence requirement

Linking theory to clinical practice aids knowledge development

Professional medical knowledge and clinical placements aided the understanding of unclear and challenging patient situations:

‘You have something to relate to that makes you feel more reassured. Just the fact that the ABCDE bundle is etched in your brain. You form a quick picture of [the intensive care patient’s] condition’ (Focus group 1).

A high level of competence was required, and more theoretical knowledge increased awareness of previous knowledge gaps:

‘Just understanding the V/Q ratios in the lungs. It was a mysterious concept [before]. [Now] you understand positive pressure ventilation much better’ (Focus group 1).

All participants expressed a desire for more clinical lectures and in-depth study of intensive care nursing in the study programme. The participants considered clinical placement experience to be most educational and applicable to intensive care nursing practice:

‘You don’t gain experience by sitting in a classroom talking about a case. When you experience it in person, you remember it better’ (Focus group 2).

Several pointed out that the practice supervisors’ competence and experience are crucial for a good learning outcome from clinical placements:

‘My supervisor didn’t have paediatric competence, so I didn’t get the opportunity to see paediatric intensive care patients in clinical practice. How does a child breathe normally or abnormally? We’ve only learned reference ranges from the textbook’ (Focus group 2).

Making clinical observations and assessments was not something they could learn by reading about it. In all focus groups, the participants discussed the challenges of having to care for paediatric intensive care patients. They had only gained minimal knowledge of and clinical experience with this patient group during their education.

Differing competence requirements at local and centralised hospitals

Local hospitals with a level 1 ICU had a requirement for general competence in intensive care nursing. Patients of all ages with differing aetiology and severity of illness were admitted here – ranging from stable, intermediate patients to unstable and critically ill intensive care patients on ventilators waiting for transferral to a higher level of treatment:

‘Here you have to be able to handle everything that comes your way. And [the] scariest part when you have to [be] both a coordinator or receive a new patient, you don't know what’s coming’ (Focus group 2).

The participants were also involved in emergency responses for cardiac arrest, stroke and trauma alert:

‘You can go from cardiac arrest to cardiac arrest until you suddenly encounter a four-week-old baby [...]. A mother runs in with a blue baby and shouts hysterically that the child is dead’ (Focus group 1).

Adult intensive care patients admitted to a level 2B ICU are a patient group that requires advanced and specialised intensive care for an extended period of time:

‘As a new graduate, it is satisfying to work with just the one patient group, as you can quickly feel competent’ (Focus group 3).

When the study participants had extensive experience with a specific patient group, it helped them develop a deeper understanding and an earlier sense of mastery in the role of intensive care nurse.

Substantial responsibility

From piecemeal and shared responsibility to sole responsibility

Some participants found that they were only given responsibility for parts of the care for ICU patients in their last clinical placement:

‘The sense of responsibility is not as strong for students, because it’s like “Okay, now I’m going to change this arterial line” […], but it’s more complex than that’ (Focus group 2).

As new graduate intensive care nurses, several discovered that patient situations were more complicated and complex than they had experienced as intensive care nursing students. Several were given substantial responsibility. In addition to caring for intensive care patients, they were also expected to supervise staff and intensive care nursing students:

‘You get appointed as the coordinator. It’s not easy without training, being responsible for the department, [but] when it’s you and 90% relief staff, that’s how it ends up sometimes’ (Focus group 3).

As new graduates, several were given sole responsibility for critically ill intensive care patients, and some of them would have liked support from a preceptor:

‘I could feel the stress of now having sole responsibility for a patient on a mechanical ventilator. Before, you had someone with experience who supported you. Now I was the one with the most experience and who was supposed to have a novice in my team’ (Focus group 1).

A number of the participants wanted to take on more responsibility for intensive care patients in their last clinical placement and for the supervisor to be more in the background. Several believed that this would have contributed to a smoother transition process.

Dealing with unexpected situations – responsibility stress

The participants reported having substantial responsibility for unstable intensive care patients, which was most prevalent at local hospitals where anaesthetists could be on call at home. They were particularly vulnerable during weekend and night shifts:

‘You can be on duty alone and have to administer a muscle relax[ant] because the patient is experiencing bronchospasm, and you have no one who can help you within a 20-minute radius. So, as intensive care nurses, we have a much greater responsibility; we’re expected to deal with any situation really’ (Focus group 1).

Several pointed out that they had acquired medical knowledge in their intensive care nursing education, making it easier to detect and manage complications that could arise in connection with the intensive care. The knowledge they learned also deepened their understanding of the responsibility they had for giving patients the right care:

‘There is more responsibility and knowledge behind the decisions and assessments we [now] make, which makes the working day easier and more predictable [...] Before, you were perhaps blissfully ignorant. Whereas now you’re unhappily knowledgeable’ (Focus group 1).

‘For my part, it felt like, with the tasks we were assigned, we were being placed on an equal footing with those who’ve been intensive care nurses for 30 years’ (Focus group 1).

One participant described a situation where a doctor with limited experienced transferred an acutely and critically ill patient to the intensive care unit for specific treatment. Upon receiving the patient, the new graduate intensive care nurse had a sense that the prescribed treatment was incorrect. The nurse felt that the doctor did not want to listen to their assessment of the situation. Further observations confirmed the intensive care nurse’s suspicion. The nurse contacted the doctor on call, who agreed that the prescribed treatment should not be administered.

Such experiences led to stress, uncertainty, unpredictability and insecurity in the beginner phase. However, the study participants reported that challenging patient situations were a learning experience that gave them the courage to take on more responsibility.

Becoming a competent intensive care nurse takes time and requires professional support and teamwork

The transition from intensive care nursing student to new graduate intensive care nurse is considered challenging

Several study participants expressed a need for closer professional follow-up and supervision, also when they were new graduate intensive care nurses. Being an intensive care nursing student one day and a qualified intensive care nurse the next was challenging for several participants. None of the participants were given the opportunity to take part in a training programme for new employees. Several had sole responsibility for intensive care patients with complex needs. The participants noted that it takes time to become a competent intensive care nurse:

‘It’s a bit like when you get your driving licence. You’re not a good driver. It takes a long time before you learn to drive a car’ (Focus group 2).

Participants with previous work experience from an ICU found that their clinical placement experience helped them absorb new theoretical knowledge:

‘I could spend energy reading up on various patient cases and delving into the pathophysiology […]. For my fellow students with no intensive care experience, I could see that there was a lot [new] to get to grips with’ (Focus group 1).

Working with colleagues with intensive care competence was educational and motivating for participants:

‘[...] that you have the opportunity to work together in pairs, or that you have people who are more experienced than [you] supporting [you] that [you] can ask. Having critically ill patients and the opportunity to ask doctors as well as experienced nurses. It’s very educational and really good. So there needs to be enough skilled staff working’ (Focus group 3).

Professional support, team cohesion, collegiality, good patient care, adequate staffing and supervision by experienced intensive care nurses and doctors were all conducive to a smooth transition process and facilitated the development of competence.

Discussion

Being a new graduate

Our study shows that new graduate intensive care nurses find the transition from intensive care nursing student to practising intensive care nurse more difficult than expected. Several felt that help to link theory to clinical practice and more responsibility in their final clinical placement could have eased the transition. They considered there to be a high level of action competence required for new graduate intensive care nurses.

According to Benner’s (26) theory, developing action competence requires iterative experiential learning and reflection on one’s own actions. According to the Regulations (1), educational institutions must provide relevant learning situations, evidence-based services and competent supervisors.

Several study participants had work experience from an ICU before starting their intensive care nursing education. According to Benner’s theory (16), these students can be considered advanced beginners, where their practical experience enhances their ability to understand different situations, but they will still need supervision and professional support.

Austenå et al. (8) claim that a higher supervision competence level is needed among intensive care nurses in Norway. Practice supervisors with supervision competence are not afraid to give intensive care nursing students more responsibility (8). The results of the study show that having an experienced practice supervisor during clinical placement is conducive to a smooth transition to working life. When intensive care nursing students are given and take on responsibility during their clinical placements, it helps them further develop their professional identity as an intensive care nurse (8), something the participants were concerned about.

The participants also experienced responsibility stress as new graduate intensive care nurses. Olsvold (27) describes responsibility stress as an intense sense of responsibility for patient care in someone who has not formally been assigned the responsibility and does not possess the relevant formal competence. An example of responsibility stress is the focus group participant who reacted to the prescribing of medical treatment by a doctor with limited experience. The participant took responsibility and contacted the doctor on call to ensure that the patient received the correct treatment.

According to the Norwegian Health Personnel Act (28), doctors have decision-making responsibility for patient’s medical care. As new employees, the participants in our study wanted a closer collaboration with experienced intensive care nurses and doctors. Responsibility stress over time is likely to hinder the transition process and perhaps lead to more intensive care nurses leaving their positions in ICUs. Teamwork and a sufficient number of staff with intensive care expertise, which our participants considered to be lacking, are likely to reduce responsibility stress.

Organisational constraints in ICUs impact on the transition

According to the Specialist Health Services Act (29), hospitals have a duty to provide the training necessary for employees to carry out their work in a responsible manner. None of our participants had received formal in-house training as a new intensive care nurse. Several of the participants experienced a ‘reality gap’ in the transition process in the form of a mismatch between acquired educational knowledge and the competence requirements in the intensive care field. Our results show that the competence requirements differ between levels 1 and 2B critical care. The apparent requirement for a high level of general competence in level 1 ICUs was surprising.

Høgbakk and Jakobsen (30) point out, in line with our study, that the high-level competence requirement in level 1 ICUs may be due to organisational constraints. For example, fewer intensive care nurses in the department and anaesthetists who are on call at home (20). There is also less extensive training and a lower level of competence in caring for ventilated patients (30), as noted by the participants in our study. The large distances between local hospitals and centralised hospitals in Norway can lead to local hospitals with level 1 critical care having to treat acutely and critically ill patients for longer than their competence level dictates (30).

The participants from level 2B critical care described a more manageable transition but also experienced high-level competence requirements. Our results showed that participants from these departments were more likely to work with a specific patient group. This facilitated the accumulation of extensive practical experience and expedited the development of action competence. Level 2B ICUs also have more resources available. For example, anaesthesiologists are on hand in the department around the clock (20).

Time to achieve the competence requirements

According to the Regulations (1), a new graduate intensive care nurse must have action competence. The results of our study show that participants who had work experience from an ICU before starting their intensive care nursing education found the transition process easier. Because of their previous experience, they were able to intervene more quickly and change the course of a situation that deviated from the norm (16, 26), as illustrated by the participant in focus group interview 1 who had to administer a muscle relaxant because the patient had a bronchospasm before the doctor arrived.

The national curriculum for postgraduate studies in intensive care nursing (31) will be discontinued on 1 July 2025. This means that local admission criteria and the requirement for two years of experience as a practising nurse may be abolished. The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) is currently conducting trailing research to examine the consequences of such a change (4). One of the consequences could be that more nurses will experience a ‘transition shock’ in their first encounter with clinical practice (9, 10, 12).

The ultimate consequence may be that new graduate intensive care nurses will leave the profession (12, 32). There is no statistical data on how many intensive care nurses leave the profession within a few years in Norway. Our study shows that building confidence and competence takes time, which aligns with Benner’s (16, 26) five stages of development.

Previous research shows that it can take two years before nurses in ICUs feel more confident and have a sense of belonging to the team (9, 10, 12). The absence of a requirement for clinical practice experience after completing a bachelor’s degree could potentially prolong the development of action competence among intensive care nurses.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The focus group interviews were conducted in connection with the first and second authors’ master’s thesis, and the article was written two years after they qualified as intensive care nurses. We have tried to challenge our pre-understanding. Increased awareness of our pre-understanding has led to a greater emphasis on the findings from the focus groups for level 1 ICUs in both the results and discussion sections. The project supervisor/last author has worked in the intensive care field for more than 15 years. This can be a strength but also a weakness, because the transition from intensive care nursing student to qualified intensive care nurse may seem more of an unfamiliar concept.

The first and second authors did not know the participants. The project supervisor knew some of the participants in the focus group interview she moderated through her work in the intensive care field of study in the master’s degree in nursing. Despite this, the participants consented to the project supervisor’s involvement. Her presence did not seem to hamper the dialogue in the focus group interview.

Individual interviews could have yielded different results and perhaps more personal experiences of not feeling competent. Further research is needed on the transition from intensive care nursing student to qualified intensive care nurse.

Conclusion

The participants found that the competence requirements were higher and the responsibility greater than expected in the transition from intensive care nursing student to qualified intensive care nurse. Experienced practice supervisors who give intensive care nursing students more responsibility during clinical placements foster a smooth transition process. Removing the admission criterion in the intensive care nursing education for two years of nursing experience after completing a bachelor’s degree may prolong the development of action competence.

To make the transition process more manageable, more time should be dedicated to supervision and collegial support. There also needs to be a greater understanding that building competence takes time. New graduate intensive care nurses also experience responsibility stress. The shortage of intensive care nurses seems to hamper the transition process and knowledge development.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research and development (R&D) team at the Surgical and Intensive Care Clinic (OPIN Clinic) at University Hospital of North Norway in Tromsø, as well as the Faculty of Health Sciences at UiT The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø and St Olav’s Hospital in Trondheim.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Sub-themes in table 5 were corrected, as one was still in Norwegian, and one had not been included.

Comments