Cow’s milk protein allergy in children from a mother’s perspective: a qualitative study

Summary

Background: Cow’s milk protein allergy is one of the most common food allergies in infants and toddlers, with an incidence of between 2 and 4.5%. Allergy management involves compliance with dietary restrictions, which means that some breastfeeding mothers will need to introduce dietary constraints on themselves, on behalf of their child. Food allergies in children affect the parent’s perception of quality of life and their self-efficacy. Such allergies can be perceived as both a social and emotional burden.

Objective: To present practice-oriented knowledge about mothers’ experiences of caring for an infant or toddler who has been diagnosed with cow’s milk protein allergy. I also wish to investigate their encounters with healthcare personnel and how they found the change to a diet free from cow’s milk protein.

Method: I carried out a qualitative study based on individual, semi-structured interviews with eight mothers of infants or toddlers who had been diagnosed with cow’s milk protein allergy .

Results: The mothers found that it was challenging to care for an infant who suffered from symptoms of cow’s milk protein allergy. The parents observed that for long periods of time, their infant experienced pain and distress, and this could cause sleep deprivation and increased stress in the mothers. All of them felt that healthcare personnel had little knowledge about cow’s milk protein allergy, provided insufficient information about managing allergies and failed to follow them up after the diagnosis had been established. In their encounters with healthcare personnel, particularly public health nurses, the mothers felt that their children’s symptoms were largely downplayed, which led to a breakdown of trust. Furthermore, the mothers found the change to a diet free from cow’s milk protein to be all-consuming. In the first phase, in particular, they spent considerable time thinking about food and planning meals at all hours.

Conclusion: Cow’s milk protein allergy is difficult to manage due to the variety of symptoms involved, and the extensive dietary restrictions. For mothers, it can be both physically and mentally demanding to cope with these symptoms on top of the dietary restrictions. They therefore expected support from healthcare personnel. In the primary health service, public health nurses play a particularly important role in providing parents with guidance and information about infant nutrition.

Cite the article

Andresen S. Cow’s milk protein allergy in children from a mother’s perspective: a qualitative study. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(95936):e-95936. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.95936en

Introduction

The incidence of food allergies has increased in recent decades. This has an impact on public health. Cow’s milk and eggs are the two foods that most commonly cause allergic reactions in infants and toddlers (1). According to the World Allergy Organisation (WAO) estimate, the incidence of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants is between 2 and 4.5% (2). The allergy is largely transitory. Over 75% of children diagnosed with cow’s milk protein allergy tolerate cow’s milk protein by the age of three (3).

Cow’s milk protein allergy has been well described in terms of incidence, symptoms and investigation, but there are few studies that focus on the parents’ perspective. Research shows that parents of children with egg and cow’s milk protein allergy have lower self-efficacy compared to parents who deal with other food allergies (4). Parents of children with multiple food allergies have stated that cow’s milk protein allergy required more planning than other allergies and had a greater adverse effect on them, both socially and emotionally (5).

The parents’ perspective has been better investigated for children with general food allergies. It has also been well described for those whose children have had anaphylactic reactions to foods, which is rarely the case with cow’s milk protein allergy. Compared to other parents, the parents of children with food allergies have poorer mental health and a lower quality of life (6). Mothers have withdrawn socially due to the child’s food allergy, and this has impacted on their perception of quality of life (6).

Food allergies are managed by avoiding the foods that cause allergic reactions. It is difficult to avoid certain foods in a diet, so personalised training is required. In children, dietary restrictions can lead to diverging development paths in terms of weight and length, due to the risk of insufficient intake of nutrients. Children with cow’s milk protein allergy are at risk of iodine, calcium and vitamin D deficiency (7).

According to the national clinical guidelines (8), health promotion and preventive work are the two most important tasks of the local authorities’ child health centres. Their objectives include promoting the healthy development of infants and toddlers and providing parental support, follow-ups and referrals. It is strongly recommended that the child’s diet is mapped by healthcare personnel and that the family should receive personalised dietary guidance from when the child is born (9). Parents of children with food allergies struggle when they realise that they have insufficient knowledge and are receiving inadequate support from healthcare personnel. This can diminish their trust in healthcare personnel (6).

Objective and research question

The study’s objective was to gain practice-oriented knowledge that could help improve the healthcare services provided for parents of children with cow’s milk protein allergy. I sought a deeper understanding of mothers’ experiences of caring for infants and toddlers who have been diagnosed with cow’s milk protein allergy. To this end, I drew up three research questions:

- Do mothers find that they are emotionally affected by their child’s cow’s milk protein allergy?

- How do mothers perceive their encounters with healthcare personnel in general, and public health nurses in particular, when their child suffers from cow’s milk protein allergy?

- What are mothers’ experiences of adapting to a diet free from cow’s milk protein?

Method

This study has a qualitative approach based on interpretive description, which is well suited for healthcare research that focuses on problems encountered in clinical practice. The goal is to gain knowledge that will benefit the field of practice (10).

Recruitment and sample

In August 2021, I shared an informative poster about the study with the Facebook group ‘Barn med melkeallergi’ (children with milk allergy), in order to recruit informants. Research shows that recruitment via Facebook can be useful, particularly in the case of specific or rare medical conditions (11). The criteria for inclusion were ‘having a child with cow’s milk protein allergy diagnosed by a doctor’, and ‘having sufficient proficiency in the Norwegian language to understand the informative note and to be interviewed in Norwegian’.

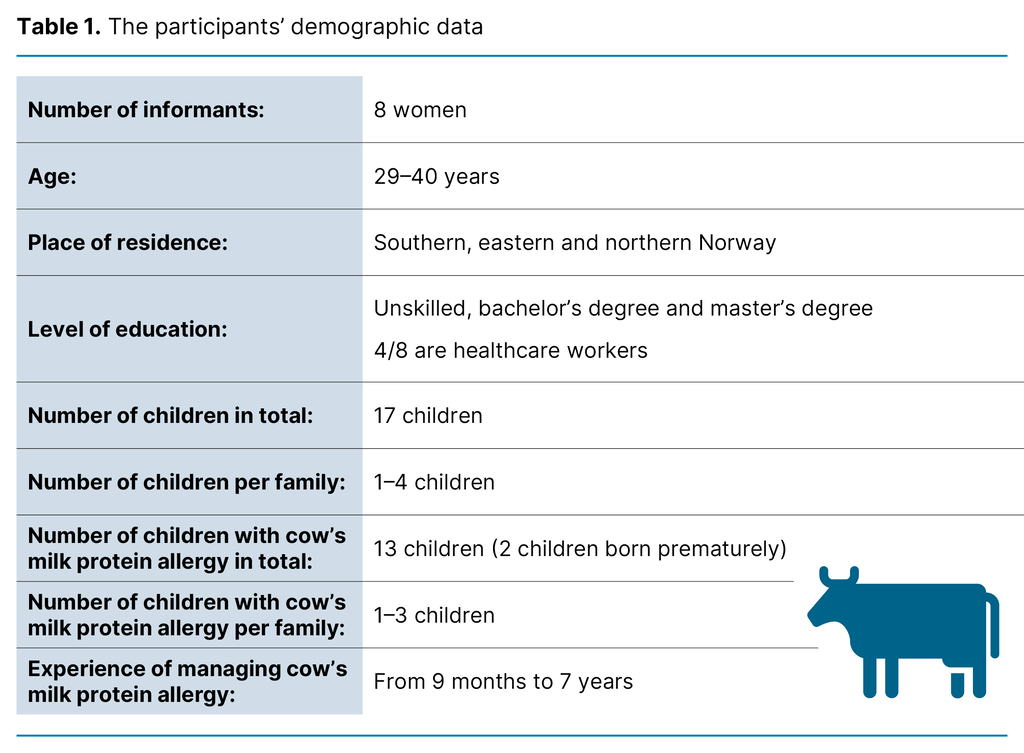

Soon after publishing the poster, I received messages from 25 mothers who were interested in the project. Most of them gave a brief description of their own situation when they got in touch. On this basis, I selected participants with a view to achieving variation in the number of allergic children per family, the severity of allergy symptoms and their geographic location in Norway. Eleven mothers were invited to take part, eight of whom accepted. Table 1 shows the participants’ demographic data.

Collecting the data

The interviews were conducted by the author via Uninett’s Zoom platform, which meets the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and relevant Norwegian legislation (12). I followed the Zoom procedures adopted by VID Specialized University for research interviews (13).

The questions in the interview guide were open-ended and inspired by themes from earlier research. The phrasing of the questions, and their sequence, were adjusted after a pilot interview. Follow-up questions about experiences at the child health centre were added, as this issue has not been studied previously in a Norwegian context. In the period between September and December 2021, I conducted eight individual semi-structured interviews, each lasting 30–70 minutes. The interviews were recorded on an audio recorder and immediately transcribed.

Analysis

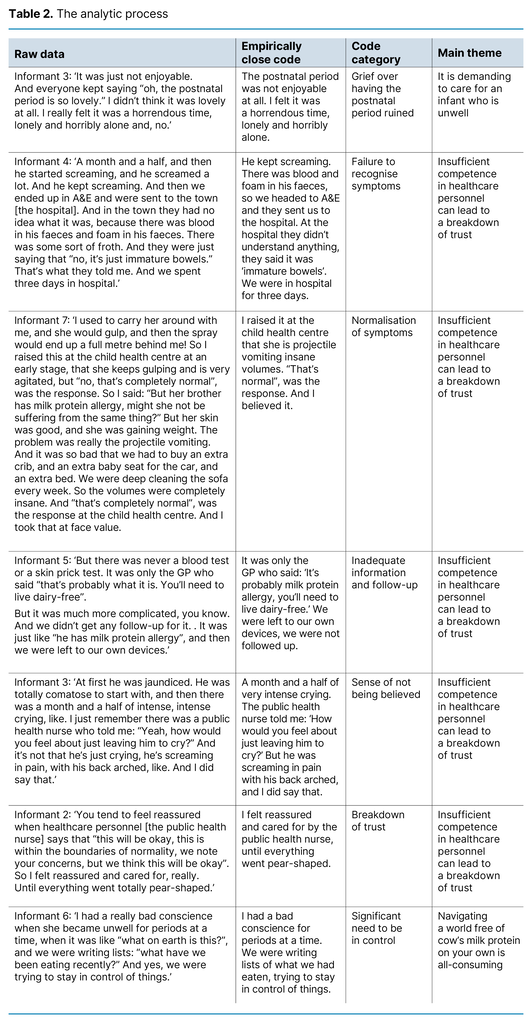

Interpretive description is an inductive research approach that allows data to be analysed according to a range of analytic methodologies (10). After careful reading, I reduced the volume of transcripts by means of empirically close codes according to Tjora’s (14) method: Stepwise-Deductive Induction (SDI). The steps from raw data to main themes are presented in Table 2. Each empirically close code and code category was created inductively and tested deductively. In line with the SDI method, a new category level, called a main theme, was created (14).

Ethical considerations

The study was assessed by Sikt − the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, reference number 429927, and approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK), reference number 218883. The informants received written and oral information about the study. Participation was voluntary, and they were informed about their right to withdraw from the study without giving a reason. They posted their written informed consent before the interview took place. The informants’ confidentiality has been protected throughout the research process.

Results

The analysis gave three main findings: (1) It is demanding to care for an infant who is unwell, (2) Insufficient competence in healthcare personnel can lead to a breakdown of trust and (3) Navigating a world free of cow’s milk protein on your own is all-consuming.

It is demanding to care for an infant who is unwell

None of the mothers had heard of cow’s milk protein allergy before their child was diagnosed. First-time parents found that the initial period was marked by uncertainty. Although they knew that infants cry, gulp and sleep to varying degrees, they did not know what to expect or what was normal. They described how challenging and tiring it was when the child expressed pain and distress for extended periods of time, and needed to be held close and comforted throughout the day and night.

The mothers suffered from sleep deprivation and stress, which adversely affected their relationship with their partner. They took sick leave during their period of statutory maternal leave and developed symptoms of post-natal depression, like despondency, social withdrawal and unhappiness:

‘It was really tough! We were at the point of leaving each other, me and my partner. […] We were completely run down, both of us. So it was really hard going.’ (informant 3)

The baby’s expressed distress, crying and gulping, described by many mothers as vomiting, led to several of them choosing to avoid social settings, like taking part in postnatal groups. Several mothers reported that they had initially assumed the infant was suffering from colic. When the child failed to gain weight, or there was blood in the faeces, or they developed a rash immediately after the first intake of baby porridge, the mothers realised it had to be something else.

They later talked about unhappy memories and felt upset that the joy of the postpartum period, which should be cherished, had been lost due to the baby’s distress and pain.

Insufficient competence in healthcare personnel can lead to a breakdown of trust

The mothers had repeatedly expressed a worry about their infant’s health in various consultations with public health nurses and doctors in both the primary and specialist health service. The infants’ symptoms were largely downplayed, particularly at the child health centre:

‘She [the public health nurse] had like a refrain she kept repeating, like: “Yes, but all children are different, all children are different, everything is normal”.’ (informant 5)

When the healthcare personnel failed to recognise the infant’s symptoms, this gave the mothers a sense of having to fight to be believed and to get the referrals they needed. When cow’s milk protein allergy was eventually put forward as a possible diagnosis, they felt left to their own devices without being provided with further information or follow-up by healthcare personnel.

None of the mothers felt that the doctor at the child health centre was involved with the allergy investigation or follow-up. There was a wide range of perceptions of GPs’ attitudes. Some felt that their GP was highly involved with the follow-up, while other GPs were perceived to be entirely disinterested or unaware of how the allergy affected the mothers’ everyday lives.

Even when food provocation tests were to be conducted, some of the mothers felt that they received no information or guidance from the doctor in charge. Those with the longest experience of having a child with allergies described it as sheer luck the times they had met healthcare personnel with in-depth knowledge about cow’s milk protein allergy.

The mothers who felt they had received help at an early stage and good follow-up from personnel outside the child health centre setting described a good relationship with their public health nurse. Even if they found that the public health nurses had inadequate knowledge about cow’s milk protein allergy, they were able to benefit from other aspects, like supportive conversations. Most of the mothers found that cow’s milk protein allergy was never a topic for discussion during consultations at the child health centre. Some were advised to google the answers themselves.

The mothers also used their own networks and spent countless hours on the internet to acquire basic knowledge about cow’s milk protein allergy. When the healthcare personnel did not meet their expectations in terms of up-to-date knowledge about cow’s milk protein allergy, the mothers experienced a breakdown of trust in them. This made them feel doubtful, and they stopped making use of the child health centre services to the extent they had originally wanted:

‘I have no confidence in them. Of course, they [the public health nurses] are nice and sweet, but I don’t think they have any knowledge, up-to-date knowledge.’ (informant 1)

Half the mothers had consulted private practitioners for allergy investigation and follow-up, since they felt there was little help forthcoming from the primary health service. Even if the mothers had told their doctor that they needed a referral to a nutritionist, this was only provided for mothers with premature babies, except for one mother who was referred to ‘The Milk School’ (15) at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål. ‘The Milk School’ was described as very useful, but it was felt that the referral had come too late.

Navigating a world free of cow’s milk protein on your own is all-consuming

The breastfeeding mothers, who themselves embarked on a diet free of cow’s milk protein on behalf of their child, described the initial phase as all-consuming. They were having to navigate in a world free from cow’s milk protein on their own, whilst also caring for a child who continued to suffer from symptoms. Finding safe foods was time-consuming, and they spent considerable time planning meals throughout the day. For some of the mothers, the situation became so challenging that they chose to stop breastfeeding.

The mothers were also worried about making mistakes that would cause more suffering for their child, and they felt that the restrictions had major implications for their diet. Alternative foods were also costly and affected large parts of their daily life:

‘I felt it was almost like studying for a bachelor’s degree. I had to read up on everything […] There is milk protein in Zendium toothpaste, I found, and I felt that, gosh! It was difficult and dispiriting to start with.’ (informant 8)

The mothers became skilful in handling the dietary constraints, which gradually became part of their new daily routine. They continued to worry about whether the child’s diet was sufficiently nutritious. They experienced repeated mishaps when their food was prepared by others. In parallel, the mothers experienced a growing need for control in order to protect their child.

Daycare and birthday celebrations became challenging arenas where the mothers felt their children were vulnerable to mishaps or had no access to food of a standard that matched everyone else’s. The mothers constantly had to inform other people and remain vigilant because others failed to grasp the severity and extent of the dietary restrictions.

Travelling involved detailed meal planning. Even after direct contact with hotels, the food on offer was inadequate. Allergen markings on restaurant menus were also not reliable. They soon found that society in general had insufficient knowledge about the difference between lactose intolerance and cow’s milk protein allergy.

Discussion

Daily life was hugely affected by the infant’s allergy symptoms and management of the allergy. The strain of living with an infant who is unwell could cause symptoms of postnatal depression in the mothers, lead to periods of sick leave, or bring parents to the verge of a relationship breakdown.

Similar findings are described by Feng et al. (16) and Moen et al. (6), who showed that mothers, in particular, experienced anxiety, depression and a diminished quality of life when their child suffered from a food allergy. Having to adhere to strict dietary constraints meant that the family restricted their social interactions, and this gave them a sense of diminished quality of life (6).

The management of food allergies has received considerable attention in recent years. Nevertheless, the parental mental health challenges associated with caring for children with food allergies have not received the same level of recognition (16).

Breastfeeding is associated with self-efficacy in the maternal role and can be linked to the child’s allergy symptoms

Lower self-efficacy levels have been found among parents of children with egg and cow’s milk protein allergy compared to parents of children with other food allergies. This was associated with the type of food that had to be avoided, not the severity of symptoms (4).

Mothers whose firstborn child developed symptoms of cow’s milk protein allergy encountered particularly big challenges. Seven of the mothers who took part in the study found that their infant reacted to cow’s milk protein through breast milk. The mothers therefore experienced a direct link between their own diet and the infant’s manifestation of allergy symptoms. The ability to breastfeed is a significant factor that has a direct impact on a mother’s self-efficacy in her maternal role (17).

Frustration and grief arise when expectations of competence and support from healthcare personnel are not being met

My study shows a more significant breakdown of trust between the mothers and the healthcare personnel than has been previously demonstrated in earlier studies. Research shows that parents’ trust in healthcare personnel is reduced when they encounter inadequate recognition and insufficient assistance with the management of food allergies in children (6).

When healthcare personnel had insufficient knowledge about symptoms, the mothers felt that their infant’s allergy was diagnosed later than necessary. They also found that healthcare personnel were lacking in understanding, and provided insufficient follow-up before, during and after the diagnostic process. This led to a breakdown of trust in the healthcare personnel.

There was also a clear expectation that the public health nurses and the doctor at the child health centre would have in-depth knowledge about cow’s milk protein allergy because they attend to virtually all children. Public trust in child health centres is high (18). Moreover, public health nurses have a close relationship with families with children. By working with the parents, they can help identify signs of food allergy in infants (19).

Under the child health centre programme, the mothers had frequent contact with public health nurses. Trust collapsed in the public health nurses who had downplayed the symptoms at an early stage, or who showed little interest in or provided little support with managing the allergy. This emotional collapse of trust was described during the interviews as irreparable, even after the diagnostic process, because the mothers later experienced a lack of follow-up and support. This finding matches earlier research showing that parents have felt they receive little support and advice from the child health centre with managing the child’s food allergies (20).

When healthcare personnel demonstrated competence in relation to cow’s milk protein allergy, the mothers believed it was based on previous experiences with other patients. It therefore appeared to them that the knowledge did not stem from guidelines or training. In 2021, in an effort to ensure that patients with food allergies are dealt with by healthcare personnel with appropriate knowledge, the regional centres for asthma, allergy and hypersensitivity published, with their collaborative partners, a practical guide to managing food allergies: ‘Praktisk veileder i håndtering av matallergi’ (21).

Several informants described frustration and grief because their postnatal period had been ruined by insufficient assistance from healthcare personnel. Feng et al. (16) write that diagnosing food allergies is no longer sufficient; the parents’ mental health must also be acknowledged.

Dietary restrictions can affect the nutritional status of both mother and child

While the mothers had a keen wish to be referred to a nutritionist, they found that healthcare personnel assumed it was easy to adhere to a diet free from cow’s milk protein, and that consequently a referral was not necessary. Research has shown that adhering to a diet free from cow’s milk protein is a massive challenge, and that parents consider the dietary restrictions to be burdensome. Finding alternative foods is also very time-consuming, and plant-based products are often more expensive (5).

Sugunasingha et al. (22) point out that there is little doubt that parents of children with food allergies have an unmet need for information. Were this need to be fulfilled, the parents’ stress would probably be reduced and their quality of life improved. Although several educational interventions have been explored, none of these methods can be fully recommended due to the low methodological quality of these studies. Future studies should have a more robust methodological design (22).

Leaving the entire nutritional responsibility to the parents is a risk, particularly since children with dietary restrictions often have an insufficient and unbalanced intake of nutrition (7).

This fact is supported by the practical guide to managing food allergies (21), which emphasises that a nutritionist or other skilled health worker should take part in the investigation and follow-up of cow’s milk protein allergy. Furthermore, breastfeeding mothers should take dietary supplements to compensate for the inadequate intake of dairy produce (21). However, none of the mothers had received personalised dietary guidance at the child health centre, and more than half of them were never referred to a nutritionist.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

By recruiting via Facebook and conducting the interviews on the Zoom platform, I was able to include mothers from a wide geographic area, with different family sizes and levels of experience with managing cow’s milk protein allergy in their own children. However, I am uncertain why parents chose to join the Facebook group. It is possible that this group of parents have experiences that are different to those who do not choose to join this group. This may be a weakness of the study.

A potential constraint is that participation in the study required technical skills. Individual interviews were an appropriate data collection method, particularly since the informants were sharing sensitive information about themselves and their children. The informants had different experiences, and the interviews provided rich answers to the research questions.

Conclusion

Cow’s milk protein allergy is a complex allergy that often requires extensive dietary restrictions. These constraints have a direct impact on family life and on the mothers’ self-efficacy. The mothers who contacted healthcare personnel for advice often felt that they were not taken seriously. They found that their concerns were downplayed. The child’s symptoms were not acknowledged, and they had an unmet need for information.

They also experienced a low level of follow-up from healthcare personnel in the public health service, and felt that the diagnostic process was too protracted. The mothers were left with deep-seated frustration and grief because the postnatal period was marked by the allergy symptoms.

Healthcare personnel should be aware of the repercussions of a diet free from cow’s milk protein for the child’s growth, the mothers’ mental health and family life. Through the national child health centre programme, public health nurses have a significant role to play in providing guidance and information about infant nutrition.

No single educational intervention currently stands out as significantly superior to others in meeting the parents’ need for information. Nevertheless, it is important that healthcare personnel who attend to infants and toddlers have expertise on cow’s milk protein allergy so that they can identify the symptoms and provide referrals, guidance and practical advice to the families as the child develops.

Future studies should investigate dietary restrictions and breastfeeding, or explore the perspectives of fathers, healthcare personnel or daycare staff.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments