Midwives’ experiences with protecting women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent in childbirth

Summary

Background: The quality of antenatal and intrapartum care in Norway is high by international standards. However, research shows that women’s rights are not adequately protected in Norway due to a lack of knowledge, a fear of accusations and heavy workloads in clinical practice.

Objective: The aim of the study was to explore midwives’ experiences with protecting women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent in childbirth.

Method: The study has a qualitative design. The data were collected in nine semi-structured interviews conducted in autumn 2022. The informants were midwives who were currently or previously employed at a Norwegian maternity unit within the past five years. Systematic text condensation was used to analyse the data.

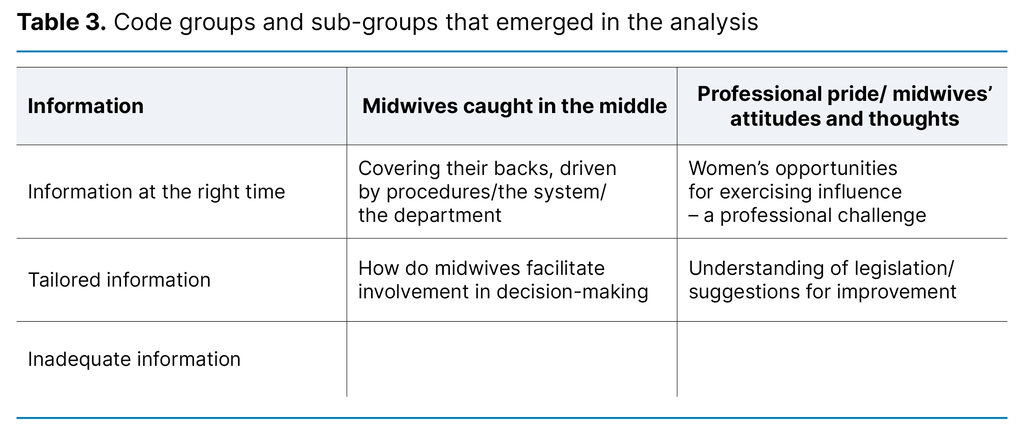

Results: The analysis resulted in three distinct categories: ‘The midwife’s adaptation and handling of information’ describes when the midwife chooses to provide information, how the information is adapted, and what the midwife chooses not to tell the patient. ‘The midwife is caught between procedures and the women’s right to involvement in decision-making’ addresses the midwife’s challenges in balancing the department’s practices with the woman’s rights. ‘The joint responsibility of the midwife and the patient for involvement in decision-making in childbirth’ describes the midwife’s thoughts on the woman’s preparation for childbirth as well as her own understanding of the woman’s rights.

Conclusion: The midwives found it challenging to protect women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent in childbirth. The study shows that there is a need for more knowledge and better facilitation in the departments to enable midwives to protect women’s rights.

Cite the article

Mageland N, Aarlien A, Galtung M, Dahl B. Midwives’ experiences with protecting women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent in childbirth. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(96697):e-96697. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.96697en

Introduction

Both the World Health Organization (WHO) (1) and the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) (2) recommend involving women receiving antenatal and intrapartum care in decision-making. In Norway, a woman’s right to be involved in health decision-making is enshrined in law (3).

Women have the right to be involved in the choice of examination and treatment methods and to receive sufficient and tailored information to help them understand the state of their health and the content of the healthcare provided, including potential risks and adverse effects. Healthcare services should be designed in collaboration with the woman to the greatest extent possible, and her opinion should be given weight. As a general rule, health care should only be provided with the woman’s consent. Informed consent is only valid if she has understood the content and significance of the information (3).

This study focuses on women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent in normal childbirth. Separate rules apply to acute situations.

How can we understand the right to be involved in decision-making in the context of childbirth? In a comment on the legislation (4), the Norwegian Directorate of Health states that the right to be involved in decision-making requires interaction between the patient and the healthcare personnel. However, it also emphasises that the patient’s right to be involved in the choice of appropriate examination and treatment methods does not negate healthcare personnel’s medical responsibility in the situation.

For a woman in labour, this means, for example, that she has the right to be involved in the choice of pain relief methods and other examination and treatment methods, as long as the choice is medically justifiable. However, she cannot freely choose a caesarean section over a vaginal birth. In situations where it is difficult to foresee the consequences of different treatment options, the need for information, advice and guidance from healthcare personnel for the woman to make a medically justifiable choice becomes greater (4). In the context of childbirth, the midwife plays an important support role for the woman.

Involvement in decision-making is an underexamined topic in Norwegian government documents on intrapartum care, but the clinical guidelines on quality in intrapartum care (Et trygt fødetilbud – kvalitetskrav til fødselsomsorgen), which are under revision, establish women’s legal right to be involved in decision-making and to information during childbirth (5).

In contrast, involvement in the form of shared decision-making was introduced in evidence-based guidelines, procedures and recommendations for antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care many years ago in England (6). In terms of intrapartum care, this means that women are involved in decision-making processes, supported in evaluating different options and given the opportunity to express her own wishes and views (7), such as choosing a birthing position or pain relief method.

Previous research shows that inadequate information and poor communication, as well as the sense of being excluded, can lead to a traumatic childbirth experience (8). To ensure a positive birth outcome, the woman should feel that she is actively participating in the decision-making process. A study by Kloester et al. (9) describes midwives’ strong desire to protect women’s rights and provide woman-centred care. Nevertheless, women’s rights are not always well protected due to a lack of knowledge, fear of accusations and legal action, and heavy workloads.

Furthermore, a study by Kennedy et al. (10) shows that consent during labour, as it is practised today, is not in accordance with legislation and clinical guidelines. The study shows that healthcare personnel want to offer women options but find a mismatch between wishes and practice. In order to be able to protect women’s right to consent, healthcare personnel need to update their knowledge on the legislation regarding consent (10). The study discusses whether midwives unconsciously use nonverbal persuasion and points out that only women who are willing to fight for their rights are able to resist the pressure from healthcare personnel (10).

A systematic literature review highlights the lack of studies addressing informed choice and decision-making in antenatal and intrapartum care in traditional hospital settings (11). The authors found that many primary studies include women who have chosen a home birth or unassisted birth – women who have made a conscious decision not to give birth in a traditional setting for various reasons (11). The purpose of our study was to explore midwives’ experiences with protecting women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent in childbirth in Norwegian maternity institutions.

Method

We employed a qualitative method and an exploratory design to investigate the midwives’ experiences (12, 13). Individual interviews and thematic analysis were considered suitable for collecting and analysing the data. We used the COREQ checklist (14) to quality assure the execution of the study.

Recruitment

We recruited informants using convenience sampling and held individual interviews based on a semi-structured interview guide (13). Recruitment began in August 2022 with a post in the Facebook group for midwives in Norway (Jordmødre i Norge), and five midwives expressed an interest. Due to the poor response, the request for participants was reposted in September 2022, but no new participants emerged. Through snowball sampling (13), we then asked our informants to share information with colleagues who might be interested. We also emailed and phoned maternity units throughout Norway, which resulted in four more participants.

Sample and data collection

The sample consisted of nine midwives. The inclusion criteria were that they had to have been employed at a Norwegian maternity unit within the last five years. Due to the geographical distances, and as per the participants’ preferences, all informants except one were interviewed via Zoom or Teams.

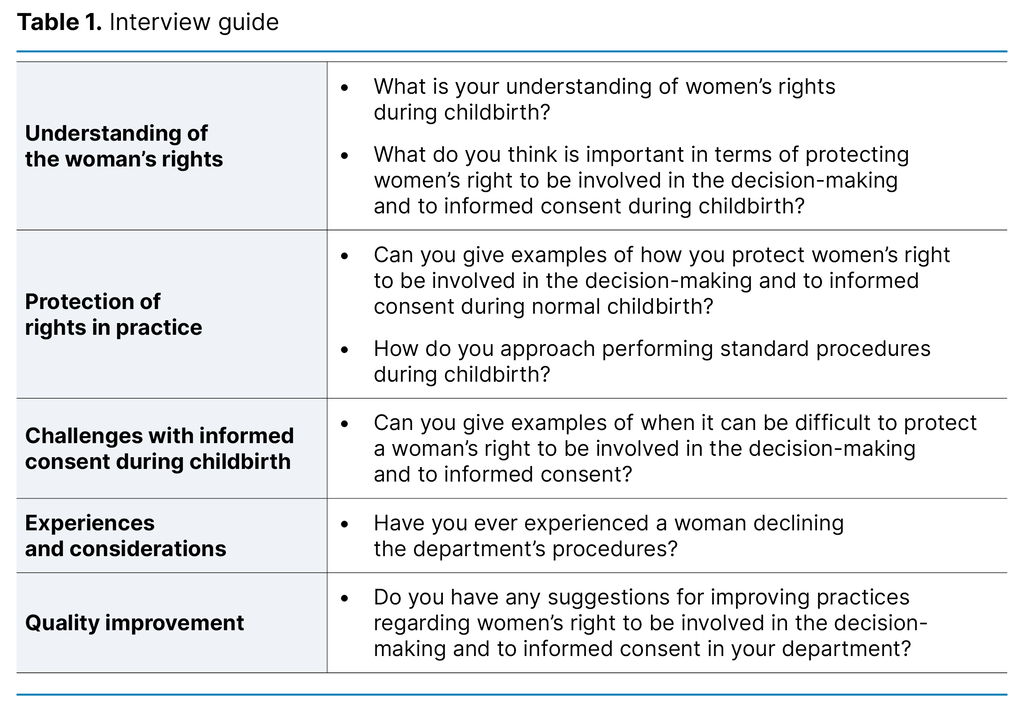

The interviews were held between September and November 2022 and lasted between 27 and 65 minutes. The authors were each assigned separate interviews, but the first interview was conducted by two of the authors. An interview guide (Table 1) consisting of seven questions was used. An audio recording was made of the interviews and this was transcribed verbatim by the interviewer.

The midwives were employed at three of Norway’s four health trusts. They were currently or previously employed in delivery rooms, maternity wards or maternity clinics. Three of the midwives were aged 30–40 years, one was in the 40–50 age group, three were in the 50–60 age group, and two were in the 60–70 age group. Their length of service varied from 8 to 30 years.

Analysis

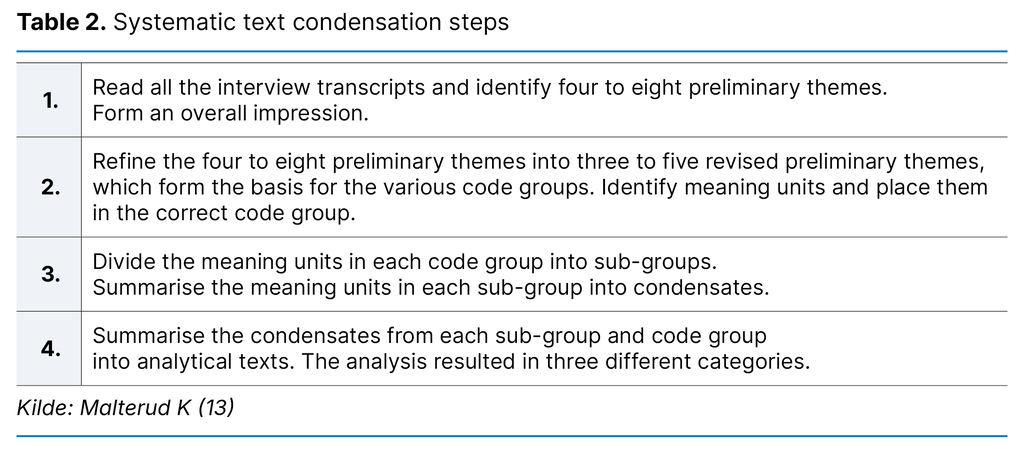

The authors performed a joint analysis of the data using systematic text condensation (STC), a cross-sectional thematic analysis method consisting of four steps (13).

In the first analysis step, we read all the interview transcripts to form an overall impression, and identified six preliminary themes. These were then revised and reduced to three preliminary themes that served as the basis for code groups. In the second analysis step, we labelled meaning units and sorted them into the relevant code groups. In the third step, we organised these meaning units into subgroups and then condensed them. Finally, each condensed unit was transformed into analytical text (13). The code groups and subgroups are presented in Table 3.

Ethical considerations

The project was reported to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), now called Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, reference number 936542. As the purpose of the study was to examine midwives’ experiences, we determined that the project fell outside the scope of the Health Research Act and that there was therefore no needed to notify the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics.

The study was conducted in line with the recommendations in the Declaration of Helsinki (15). The midwives were sent written information about the study before they agreed to participate. One participant gave oral consent. The midwives who were interviewed via Teams or Zoom consented by logging on to the Teams or Zoom link. They were informed of their right to withdraw from the study without giving a reason, up until completion of the data analysis.

Results

The midwife’s adaptation and handling of information

The midwives felt that information should be provided at the right time, giving the woman time to reflect on what was said and enabling her to give informed consent. Time pressures forced them into harsh prioritising. When faced with choosing critical care, providing information took a back seat. The midwives were in a better position to provide useful information to women giving birth at a time when the department was quiet compared to when it was busy. The women accepted the procedures suggested if they were given information and explanations.

However, it was challenging for the midwives to provide information and obtain consent in the later stages of labour when the pain was more intense. The midwives prioritised giving information between contractions and reiterated it as necessary. During the pushing stage, the information they provided was brief. The best approach was to prepare the women well in advance of the birth. Ideally, information about the women’s rights, as well as the benefits and drawbacks of interventions, should be provided as part of the antenatal care:

‘If you’re going to explain it in a way that she’ll truly be able to give her consent, you need to do it well in advance. It’s too late once the head is crowning.’ (Informant 2)

Some midwives were surprised by what their colleagues chose to spend time explaining, but they understood that perceptions of situations could differ. They emphasised the importance of ‘sensing’ how receptive the woman was, and tailored the information they provided accordingly.

The midwives found that women who understood the reason behind something being done in the delivery room were less afraid. They therefore tried to avoid using complicated words and phrases. They noted that when a woman was scared, providing information that she was able to understand was challenging. In cases of information overload, when the woman was losing her focus, the midwives allied themselves with her partner:

‘I often find that the woman’s partner can be a team player because they aren’t as overwhelmed as the woman. So, working with the partner is a good idea.’ (Informant 1)

The midwives made sure that the information they provided aligned with what they themselves considered best practice, in the hope that the woman would cooperate. When the midwives recommended interventions, they rarely mentioned adverse effects and drawbacks in order to avoid alarming the women. If a woman did not ask about adverse effects, the midwives did not mention them. Some did inform the women of drawbacks but were mindful of how they phrased it. One midwife gave an example of how she would never phrase things:

‘I’m making an incision now just to be on the safe side. It will hurt more, and will be more painful to heal than a second-degree tear.’ (Informant 3)

She was aware that by withholding information about the drawbacks it would be easier to gain approval for performing an episiotomy (an incision made in the perineum to prevent uncontrolled large tears, particularly when a quick delivery is needed).

The midwife is caught between procedures and the women’s right to involvement in decision-making

The midwives sometimes felt compelled to perform procedures they disagreed with. They found that clinical management expected more monitoring than was recommended in research, such as requiring admission cardiotocography (CTG) for all women. Most of the midwives felt they had to be loyal to their employer in order avoid a reprimand.

One midwife used to tell women, ‘This is the department’s procedure, that’s why I’m doing it this way’ (Informant 2). She rarely faced resistance, as most people assumed the hospital knew best. The midwives explained that it would be the midwives themselves who would suffer the consequences if they failed to follow the procedure. However, the more experienced midwives often chose to deviate from the procedure to enable the woman to be involved in decision-making. They justified this by saying they were more confident in their abilities than newly qualified colleagues and were less afraid of being reprimanded:

‘Adhering to procedures while also protecting the woman’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent is, I would say, a bit of a utopian expectation.’ (Informant 9)

It was difficult to fulfil a woman’s wishes and protect her rights in addition to taking responsibility for her child, while also adhering to the department’s practices. Sometimes, for medical reasons, the midwives had to perform procedures against a woman’s wishes.

One challenge that was mentioned was that if a woman did not want to be catheterised but had two litres of urine in her bladder, the midwife would not give up until the woman understood the consequences of not being catheterised. Some midwives were afraid of doing something wrong or overlooking something, and they believed this was driven by a need for control that possibly stemmed from fear. They performed interventions that were not part of the procedure, ‘just in case’:

‘In any case, I think we focus more on covering our backs than on allowing them to have a say and make informed choices.’ (Informant 3)

The midwives questioned whether the women actually had a real choice. Several reflected on how they phrased their language. They often presented measures during labour as suggestions or recommendations, because as soon as they formulated the proposed measure as a question, they had to consider the possibility of the woman refusing. One such example was: ‘I’m now going to [...] because [...].’ They then performed the procedure without asking the woman. One midwife described this as a form of coercion and thought it would have been a better experience for the woman if she had been given the opportunity to take part in the decision-making:

‘I present it as part of our standard practices, this is how we do things here. I don’t ask directly if she agrees.’ (Informant 6)

The joint responsibility of the midwife and the patient for involvement in decision-making in childbirth

Women who had attended antenatal classes were more aware of their rights and the opportunity to influence the childbirth process with a birth plan. Some of the midwives applauded this, while others found it problematic. One midwife thought that colleagues who questioned it perhaps felt that their professional competence was being challenged. Another believed that it was primarily the most experienced and authoritative midwives who found the use of a birth plan problematic.

Birth plans were challenging when women had a very fixed idea about what they wanted, and all the midwives emphasised the importance of women being flexible during labour. There was no point in planning the birth in detail, as childbirth is inherently unpredictable. However, most of the midwives believed that antenatal classes and birth plans were effective tools for facilitating women’s involvement in decision-making. One informant said the following:

‘She herself has a responsibility for her labour progressing, so she needs to be informed about what we want to do and why. If she wants to lie on her back in labour for eight hours, let her get on with it.’ (Informant 6)

All informants agreed that there was potential for improvement in relation to their own and the department’s knowledge of the legislation on women’s rights during childbirth. One question raised was, ‘What would I want if I was in this situation?’ Many felt that introspection and effort were needed to change established behaviours. Suggestions for improvement included holding training days on the patient’s involvement in decision-making. Several highlighted the value of sharing experiences, thoughts and perspectives with each other.

The midwives expressed uncertainty about the legislation and were unable to quote any of its content. Some were more up to date than others, but most engaged with the legislation at a subconscious level; they reasoned that women have the right to be involved in decision-making and to give informed consent:

‘At some point, I’ve probably known something about patients’ rights. But the laws on that are not foremost in my mind.’ (Informant 5)

Discussion

Right to information – a challenge in clinical practice?

Women in labour have the right to tailored information (3), but the midwives in the study rarely mentioned adverse effects and drawbacks of various interventions in order to avoid alarming the women. One of the midwives described this as a form of coercion. When a suggestion is framed as a question, it opens up the possibility of the woman responding with either yes or no. If the woman declined the proposed intervention, the midwife was faced with a dilemma. This dilemma was avoided by refraining from providing the woman with sufficient information to make an informed choice. Consequently, she deprived the woman of the opportunity to be involved in decision-making and to make a real choice.

This finding is consistent with other research indicating that it is not standard procedure to provide information about the benefits and drawbacks, and that this practice may be linked to midwives’ reluctance to involve women in the decision-making (16). Another explanation could be that providing detailed information is time-consuming. In order to make an informed choice, the woman needs time to reflect on the information she is given, which can be challenging in a busy department. Although shared decision-making is not yet common practice in Norwegian maternity wards, documents on intrapartum care recognise women’s legal right to receive information during childbirth (5).

Providing the women with adequate information can give them a greater opportunity to be involved in decision-making, helping them avoid becoming a passive participant in their own childbirth process (8). Furthermore, studies show that healthcare personnel’s reluctance to provide information (16–18) can contribute to traumatic childbirth experiences (8, 19). Trying to shield women by withholding information can therefore be counterproductive to the midwives’ intentions.

Active involvement in decision-making – a real possibility?

According to Joseph-Williams et al. (20), women may be trapped in their desire to be a ‘good’ patient, where they are passive and compliant and take up little space. The study shows that healthcare personnel believe it is their job to make decisions on the patient’s behalf, as they know what is best for them. Similar findings were reported by the midwives in our study and are supported by research indicating that some women do not actually want to be involved in health decision-making (21).

In contrast, other studies show that while healthcare personnel may believe a woman does not want to be involved in decision-making, the reality might be that she does. However, she is being deprived of this opportunity because she has been given inadequate information (8) or does not wish to bear sole responsibility (19).

The midwives in the study reported how some women used a birth plan to be actively involved in the decision-making during labour. Devising a birth plan after consulting with the midwife and maintaining an open dialogue about it during labour has been shown to enhance the birth experience (22), foster greater involvement in the decision-making and promote a sense of control (23, 24).

All the midwives agreed that birth plans are a useful tool for childbirth, but they also raised concerns about some women setting specific demands and wishes that are unrealistic. The midwives felt that if the women’s wishes in the birth plan were too detailed, they were less inclined to adapt. This could be professionally challenging for experienced midwives.

This finding is consistent with other studies (25, 26), which show that experienced midwives in Norway have a strong identity linked to the midwifery profession. They often viewed the women’s expectations during childbirth as a long ‘wish list’ of demands that could be perceived as offensive, and they felt that the women doubted their midwifery knowledge and experience. This tension can pose a challenge to the midwife’s professional autonomy and hinder effective collaboration between the midwife and the patient.

The quote above from Informant 6, regarding the shared responsibility for labour progressing, illustrates the importance of information, communication and collaboration during childbirth. Although the women have a legal right to be involved in decision-making, the midwife has a professional responsibility in the situation. The midwife must balance the woman’s wishes and rights with her own duty to provide appropriate medical care.

Clinical guidelines and procedures – basis for negotiation?

The midwives in the study sometimes felt compelled to perform procedures they considered inappropriate. They felt they had to be loyal to their employer, and that it would be commented on if they did not adhere to procedures. Several studies indicate that midwives feel pressured into adhering to the department’s practices and procedures, even when this undermines the patient’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent (16, 27, 28).

The study by Feeley et al. (16) found that midwives engaged in negotiations with the women to find a compromise between fulfilling the woman’s wishes and adhering to the department’s practices. This finding is consistent with our own results. Midwives found the situation challenging because they felt that internal procedures and clinical guidelines did not adequately address women’s right to be involved in the decision-making during childbirth. Nevertheless, they tended to adhere more to the department’s procedures and clinical guidelines than to the legislation. A British study shows that no facilitation is made for midwives to protect women’s rights while simultaneously following departmental guidelines (28).

In our study, several experienced midwives chose to deviate from the department’s procedures to enable the women to be involved in decision-making, for example by omitting the routine use of admission CTG. They justified this by saying they were more confident in their abilities than newly qualified colleagues and were willing to take responsibility for their decisions. Similar findings are seen in a study that describes how the midwife’s autonomy is more crucial than departmental procedures for ensuring a normal birth (25).

It is interesting to note that the midwives who chose to deviate from or only partly adhere to procedures at larger maternity wards were regarded as ‘alternative’ by their colleagues (25), while the midwives concerned perceived themselves as a reassuring presence for the women in their care. This finding raises thought-provoking questions about what constitutes ‘valid’ knowledge in the midwifery profession, as well as the understanding of the midwife’s autonomy versus the woman’s rights during childbirth.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The authors are midwives with experience in intrapartum and postpartum care, professional development and education. Our interest in the topic arose after observing how practices regarding the protection of women’s right to be involved in decision-making and to informed consent differed across clinical settings. We recognise that women are becoming increasingly aware of their rights during childbirth, but challenges often arise when trying to balance the requirement for medically justifiable care with the women’s right to be involved in decision-making.

Qualitative design and individual interviews were suitable methods for shedding light on the study’s research question (13). Similarly, a cross-sectional thematic analysis was an appropriate choice given the scope of our data (13). However, our limited research experience may have impacted on the quality of the interviews, particularly our ability to follow up on important points in the first interviews.

Using social media in the recruitment process enabled us to effectively communicate information about the study to a wide audience of midwives. One of the strengths of the study was the participation of midwives from large and small maternity units across three of Norway’s four health trusts. However, the recruitment was challenging. This could be due to a lack of interest in the topic, or perhaps a reluctance to comment on it, but it could also be related to our choice to recruit via social media.

The closed Facebook group for midwives in Norway (Jordmødre i Norge) has over 3000 members and is frequently used to recruit participants for various studies. We cannot ignore the possibility that the volume of requests has led to ‘fatigue’ within the group, as members mostly need to participate in the research in their leisure time. We also cannot rule out the possibility that midwives who were particularly interested in the topic contacted us with a desire to participate, which may represent a bias in our sample.

Conducting the interviews via Zoom and Teams enabled us to recruit participants from across the country. The midwives could respond from the comfort of their own homes, making it easier to fit the interview into their busy daily routines. The participants reported feeling comfortable with digital video platforms, having grown accustomed to them over the years of the pandemic. However, we cannot ignore the fact that it can be easier to establish a good rapport and identify non-verbal cues in in-person interviews compared to remote interviews.

Conclusion

The midwives found it challenging to protect the women’s right to be involved in the decision-making and to informed consent during childbirth. Balancing the protection of women’s rights while being expected to adhere to the department’s practices was particularly challenging.

The study also revealed a need to improve practices and update clinical guidelines and procedures, with a strong focus on opportunities for patient involvement and shared decision-making. Greater involvement in decision-making can contribute to a more positive childbirth experience and give a woman a greater sense of ownership over her own childbirth process.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments