‘Mind the gap’: nurses’ experiences of the transition of patients with terminal cancer from hospital to home

Summary

Background: Patients living with terminal cancer often need palliative care from both the primary and the specialist health services. Facilitating safe transition from hospital to home is a key nursing task. Transferring a patient from one place to another involves a handover of clinical responsibility from one group of healthcare personnel to another. This poses a risk to patients’ safety along with a lack of follow-up.

Objective: The objective of the study was to gain greater insight into the experiences of hospital and community nurses with the transfer of patients with terminal cancer.

Method: The study has a qualitative design. We carried out two focus group interviews with a total of eleven nurses employed in the primary and specialist health services. We analysed the transcribed focus group interviews using systematic text condensation. Our discussion of the study’s findings is informed by Afaf Meleis’ transitions theory.

Results: We identified two themes in the analysis: ‘Unsystematic planning’ and ‘Tacit expectations’. Patient transitions appeared to be an unpredictable process characterised by randomness. Both hospital and community nurses had a very busy working day and felt a need for closer dialogue and interaction. Community nurses thought it was vital that the expectations of the patient and their family were clarified with the service providers prior to discharge from hospital. It was also essential that the necessary information, medication and equipment were available prior to transfer to the home.

Conclusion: The study shows that both hospital and community nurses feel a responsibility for patient transitions and compensate for the shortcomings that arise. There is a need to clarify the nurses’ expectations as to what can be done by the home care services or at the hospital prior to patient transitions. The study highlights the need for more systematic interaction. Greater attention should be paid to the fact that the patient’s needs may change in a different context.

Cite the article

Sørensen J, Ellingsen S. ‘Mind the gap’: nurses’ experiences of the transition of patients with terminal cancer from hospital to home . Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(97576):e-97576. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.97576en

Introduction

The nurse has a unique role and pivotal function in helping the patient to deal with and master different transitions, and preventing the negative impacts a transition may have on health and illness (1–3). A transition may have negative, health-related consequences, but care measures can improve the quality of transitions and thus influence the outcome (1, 2, 4–8).

The patient’s condition, nursing-related factors and organisational aspects are some of the elements that affect the outcome of transitions for patients with cancer (8).

Patients with terminal cancer are in continuous state of transition due to a rapidly progressing disease and bodily changes (9). This means that these patients may need palliative care, nursing and treatment from both the primary and specialist health services (10).

They risk being moved to different places, with another group of health personnel assuming responsibility for their treatment and care (9). Such a transition may make patients and their families feel insecure. Therefore not only do they need information and practical support but also to be involved in the planning of the transition (8, 11–13).

Ensuring the quality of patient transitions is a familiar and long-standing challenge (14). The goal has been to achieve seamless patient transitions between the primary and specialist health services. Although various national measures have been implemented to ensure their quality, adverse events nevertheless still occur (14, 15).

The ‘Cancer patient pathway’ was intended to be implemented in the different health services by the end of 2023. The purpose is to give the patient reassurance and predictability. The intervention includes three joint meetings with conversations about the patient’s life situation over and beyond the cancer treatment. Moreover, the patient must receive follow-up after being informed of the cancer diagnosis. The first conversation is initiated by the health trust while the second and third conversations are initiated by the primary health service (16–18).

Research emphasises the importance of collaboration between nurses and other health personnel at different levels of the health service (7). Close collaboration between nurses, patients and their family is important in creating trust and reassurance in the home setting (19). When the hospital fails to provide sufficient information about the prognosis or treatment targets, it is challenging to take over the care of the patient (20). Differing views about what information should be emphasised in the exchange between community nurses and specialist health care nurses may make cooperation difficult (21, 22).

If there is little time for planning, dialogue and interaction, the danger of adverse events increases (19, 21–23). Inadequate planning of the discharge entails additional work afterwards (21, 22, 24). Research shows that interventions can improve patient safety, but this does not necessarily mean that they will make the patient more satisfied (25). We need more knowledge about the care of patients with cancer at the transition stage as this may lead to more satisfied patients and prevent re-admissions to hospital (8).

Transitions are described as ‘a passage from one life phase, condition or status to another’ (2, p. 25). Afaf Meleis’ transitions theory can make nurses more aware of what promotes good patient transitions (7). The main focus of the theory is to promote well-being and coping strategies by identifying critical points or risk areas during the transition. In this way, we can avoid deterioration in the condition of those undergoing a transition, and give their families greater understanding of what a transition entails (4).

Meleis describes different types of transition, such as developmental, health-related, organisational and situational (5, 26). Discharge from a hospital can be regarded as a transitional experience that requires the nurse’s attentiveness (1, 26). The transitions theory provides a framework for clinicians to describe the critical needs of patients during hospitalisation, discharge, restitution and transfer. This may have implications for nursing practice (5). Our discussion of the study’s findings is informed by Afaf Meleis’ transitions theory.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain greater insight into nurses’ experiences of the transfer of patients with terminal cancer from hospital to home

Method

Design

The study has an explorative qualitative design with focus group interviews (27–29).

Recruitment and sample

We recruited a strategic sample (28) of nurses who had experience of the discharge and reception of patients with terminal cancer.

The participants were recruited from four wards in a large hospital in Norway and three of the local authorities that form part of the health trust in question. Managers and cancer coordinators were excluded.

The ward managers and the various municipal home care services were the first author’s contacts, and they passed on information about the study to their staff. Those who wished to participate contacted the first author by email or text message. As it was challenging to recruit a sufficient number of participants from the specialist health service, we also used snowball recruitment (27), whereby nurses in the first author’s circle of acquaintances informed their own circle about the study, and they in turn informed others.

Those who wished to participate contacted the first author directly via email or text message, and then received written information about the study by email. We recruited two informants in this way.

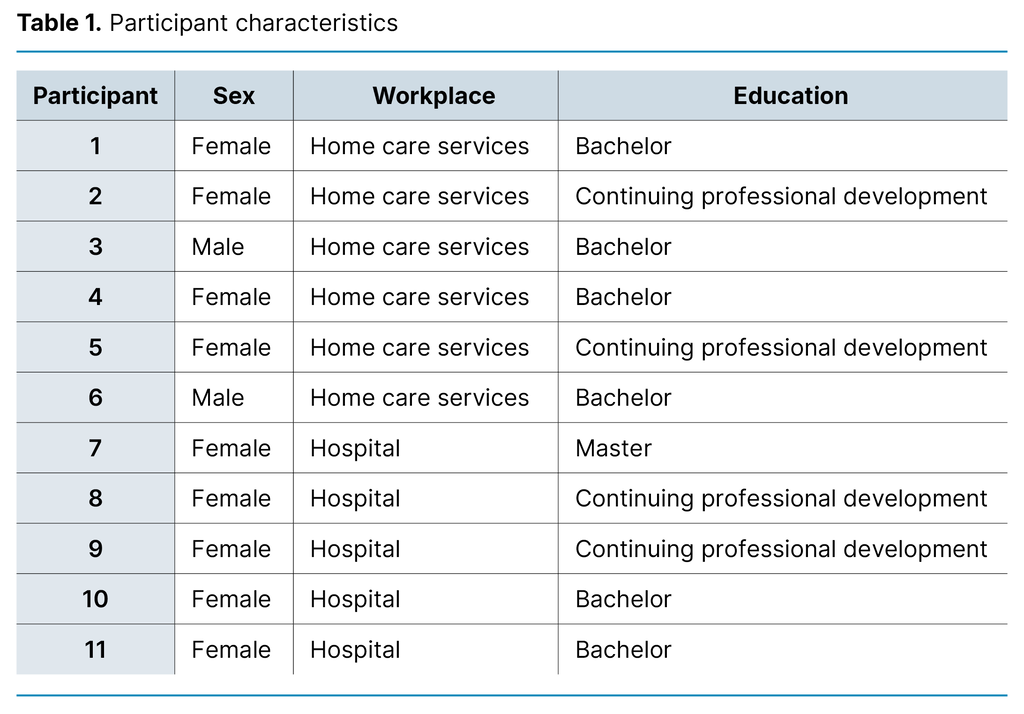

A total of 15 nurses agreed to participate. Two of these withdrew: one withdrew when the first author contacted them to arrange a date for the focus group interview, and the other withdrew the day before the focus group interview. A further two participants were unable to attend because none of the alternative interview dates suited them. A total of eleven nurses attended the two focus group interviews (Table 1). They were aged from 24 to 52 years, with a median age of 42. Their work experience ranged from 6 months to 26 years.

Data collection

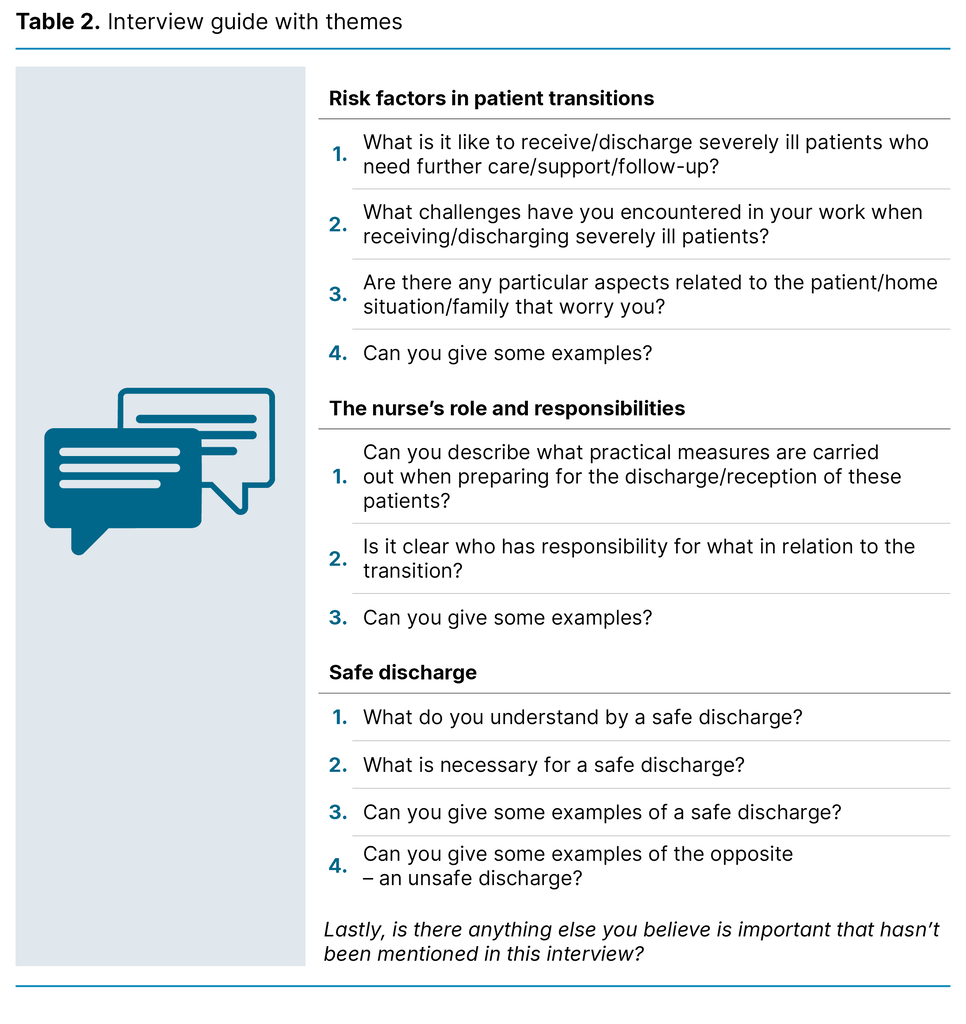

We devised a semi-structured interview guide with three themes (28, 29): ‘Risk factors in patient transitions’, ‘The nurse’s role and responsibilities’, and ‘Safe discharge’. Each theme had related questions. We conducted a pilot focus group interview with four nurses from the first author’s workplace to practice carrying out an interview and to check whether the questions in the guide elucidated the theme fully. No changes were made in the interview guide.

Next we carried out two focus group interviews – the first with six participants from the home care services, and the second with five participants from the hospital. The pilot and the two focus group interviews were conducted by the first author and a co-moderator (28) in a hospital meeting room.

The interviews lasted 59 and 65 minutes, respectively. The themes in the interview guide were presented in the same manner in all the interviews. The questions that had been prepared in advance were hardly required because the informants largely kept to the various themes in the interview guide when talking to each other. At the end, they were all asked the last backup question in the interview guide: ‘Lastly, is there anything else you believe is important that hasn’t been mentioned in this interview?’

At the end of the interviews, the co-moderator summarised the essence of what had been discussed, and the informants could give feedback. The focus group interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed by the first author. Table 2 presents the interview guide.

Analysis

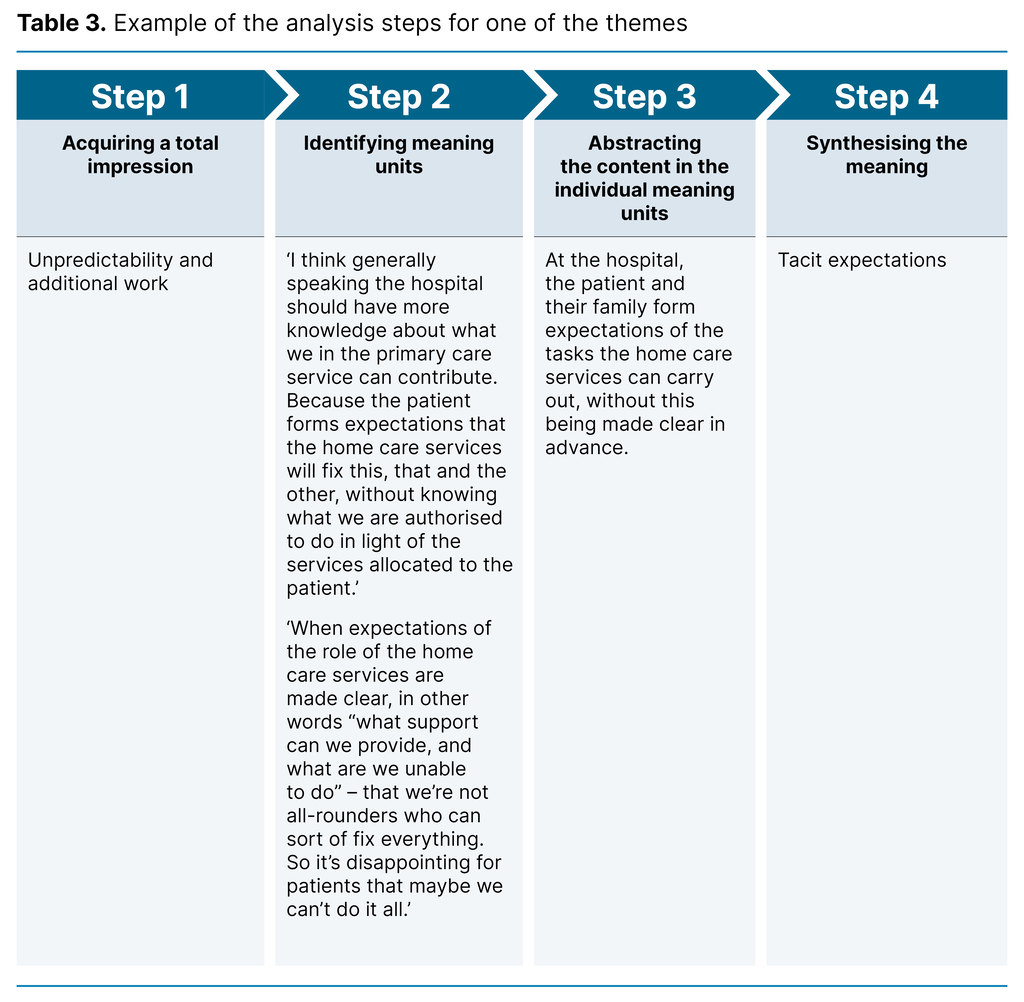

The interviews were analysed using systematic text condensation – a thematic cross-case analysis consisting of four steps (28). We used highlighter pens to colour code text on paper, then the meaning units were cut out and sorted.

Step 1 consisted of acquiring a total impression. First the transcribed interviews were read and reread several times to gain a total impression of the entire dataset. In addition, eight preliminary themes were identified.

At step 2, we identified meaning units. The material was then systematically reviewed to identify what was relevant to the research question. We set aside the material that was not found relevant. As a result of this process, the preliminary themes were reduced from eight to four code groups.

At step 3, we abstracted the content of the individual meaning units. These were processed and sorted into sub-groups based on the nuances observed. We summarised the sorted information by condensing the content of the sub-group and using pertinent quotations.

At step 4, we synthesised the meaning of the content. Finally, we formulated an analytical text for each sub-group, and assessed the pertinent quotations to check if they still illustrated the analytical text. Throughout the analytical process, we evaluated the titles of the code group and sub-groups, and refined these in order to capture the content (28). Table 3 gives an example of the analytical steps for one theme.

Ethical considerations

The study was reported to Sikt, the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, reference number 146020. Participation in the study was voluntary, and we obtained written informed consent. The participants recruited by the snowball method received information and a consent form by email, and the remaining participants received this from their supervisor. They sent their written consent to the first author. We processed all information and data material in line with the guidelines for research ethics (30).

The audio files were deleted after transcription. The transcribed material did not contain any personally identifiable data. The first author is affiliated with the institution where the study was conducted. Three of the informants knew the first author through her position as a coordinator at the Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, but they had no personal relationship. The informants who withdrew had no knowledge of or relationship with the first author.

Results

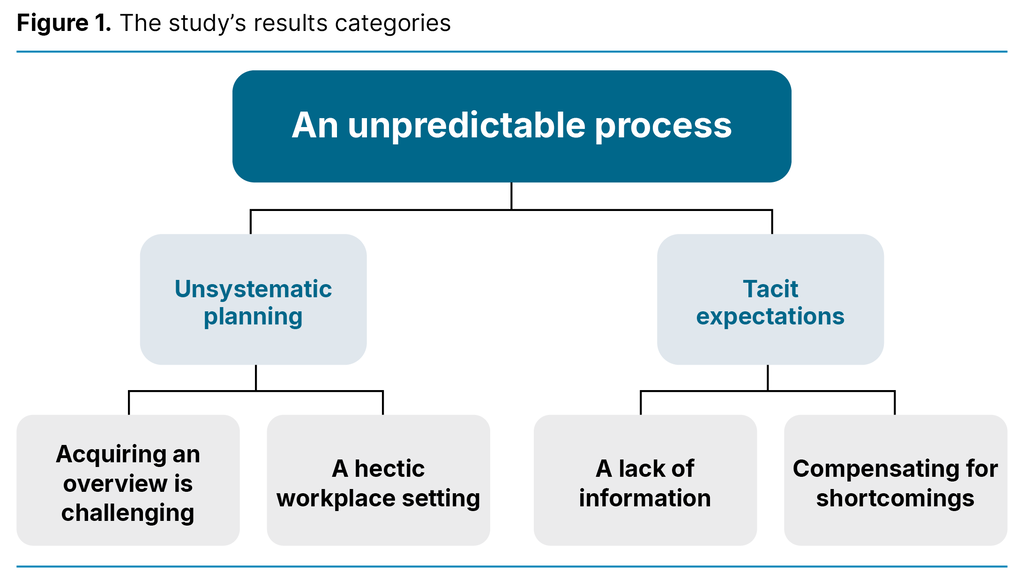

As the entire process of facilitating and implementing patient transitions was characterized by randomness, the overarching theme of the study was ‘An unpredictable process’. Both hospital and community nurses found it impossible to predict whether the necessary aids would be in place in the patient’s home, if the discharge report would be available when the patient was discharged, and if prescriptions for the prescribed medications had been written.

The analysis resulted in the following two main categories: ‘Unsystematic planning’ and ‘Tacit expectations’, each with two sub-groups (Figure 1).

Unsystematic planning

There were variations in how the planning of a patient transition was carried out and documented. The different hospital wards had different procedures for documenting the planning and progress of a patient transition in the patient record. When progress was not documented systematically, this was extremely challenging. Reading through several documents in the patient record to find the right information could be time-consuming. Even though there were clear procedures for how this work was to be accomplished, these were not always followed:

‘We have a discharge plan, but I think it’s quite poor. It’s almost better that one person has the main responsibility, someone who is more involved than all the others. […] People forget to use it [the discharge plan]. It’s not always updated. What has been done? What hasn’t been done? So there’s a bit of a muddle at the end. And with the high turnover of personnel, shifts, all kinds of things. […] I think there’s kind of a capacity problem really’ (Participant 10 from the hospital).

Acquiring an overview is challenging

The hospital nurses emphasised that they needed information from various actors, such as the attending doctor at the hospital, the patient’s GP, the hospital and community nurses, the patients and their families:

‘There are conversations with the patient about applying for home care services, for example. Then we must help them with the application and see that it’s sent. And we must have a meeting with the local authority, organise things, and adapt the home with the help of the local authority. Communicate with the local authority about when the patient is to be discharged. It’s a big area, and there’s a lot to cover. A lot of tasks to do when preparing for people with late-stage cancer to stay comfortably at home’ (Participant 7 from the hospital).

A hectic workplace setting

Both hospital and community nurses described the planning of patient transitions as time-consuming. The hospital nurses found that they had only a short time to prepare for a patient transition:

‘Maybe a reason for things often being forgotten is that we have too much to do. A lot has to be done at the same time. Then you forget it, because we’re not programmed machines’ (Participant 9 from the hospital).’

The hospital nurses found that insufficient time was set aside for work on patient transitions. Consequently, this was often done in between other tasks. The community nurses also usually found that they needed more time with patients than was allocated:

‘Patients are allocated services. But 20 minutes for conversation, what happened to that? You’re expected to do this at the same time as caring for a PICC line or other tasks. I think that’s a shortcoming’ (Participant 4 from the home care services).

Community nurses had a feeling that they were only given time to carry out practical tasks when visiting patients. They wanted to give the patient all-round care but were under pressure because the time allocated was insufficient.

Tacit expectations

The nurses’ expectations of what should be done by the home care services or the hospital were not clarified. The hospital nurses expected the community nurses to correct errors or shortcomings that were identified after the patient transition, although this was really the responsibility of the hospital.

The community nurses expected that as much as possible had been arranged before the patient came home, but with no dialogue about what this entailed for the individual patient. When expectations were not made clear, or services were promised that could not be provided, this could lead to frustration and disappointment not only for patients and their families but also for those working in the home care services:

‘When expectations of the role of the home care services are made clear, in other words “what support can we provide, and what are we unable to do” – that we’re not all-rounders who can sort of fix everything. So it’s disappointing for patients that maybe we can’t do it all’ (Participant 1 from the home care services).

Both the hospital and community nurses described patient transitions as successful when it was clear what patients and their families wanted, who was involved, what tasks were to be done prior to discharge, and who was responsible for carrying them out.

A lack of information

The varying quality of the exchange of information between hospital and community nurses could lead to unpredictable planning of patient transitions. Community nurses only had access to information provided via electronic care messages and telephone calls.

The nurses often needed to talk together because the electronic care messages did not bring out the nuances in the patient’s situation in the same way as an oral exchange. When home care services received patients with complex health problems, liaison meetings were held.

It was important for the home care services to have updated information about the patient and the discharge report in particular. When preparing for the patient’s return home, they usually called the hospital nurses directly if anything was unclear. On several occasions they had discovered that the hospital’s information about the patient did not correspond with what they themselves experienced when they met the patient in their home. Then they spent a considerable amount of time trying to contact the person who had the information they needed, since many actors were involved:

‘If you need a prescription, who do you then call? Do you call the GP, the palliative team or the [hospital] department? So it should have been made clear whether the GP is included or not. And as for the palliative team, they’re only available from 8am to 4pm, right? After that you must contact the ward’ (Participant 2 from the home care services).

Compensating for shortcomings

When there were errors or shortcomings in patient transitions, these were often rectified because the community nurses informed the hospital or put them right themselves:

‘We get phone calls about all sorts of things. But I feel that we often manage to fix it ourselves. We haven’t done the job properly, haven’t sent all the paperwork or followed the procedures. But it works out, the home care services get in touch’ (Participant 10 from the hospital).

Community nurses often felt they were on their own with the work of unravelling and solving problems related to patient transitions when there were deficiencies. With no specific contacts to turn to, nurses often felt that they were alone. When equipment or medications were lacking, the community nurses themselves procured these in order to avoid negative consequences for the patient.

‘Maybe the patient is sent home without the right equipment. […] Sometimes we’ve had to go to the hospital or medical assistive equipment centre and collect things during working hours. Just so we can save the situation’ (Participant 6 from the home care services).

Efforts to obtain equipment or medications might result in nurses having no time to eat lunch. In some cases it meant that they had to work overtime to make up for the lost working hours. Afternoons, evenings, public holidays and holiday periods were mentioned as being difficult times for the discharge of patients from hospital.

Discussion

To achieve a smooth patient transition, it is vital to be aware that this entails change, and that there are critical points in the change process (4). In this study, two critical points stood out: information exchange and unclear expectations.

Information exchange

This study identified the unpredictability of the entire process of patient transitions from hospital to home. There was a considerable lack of clarity, and the hospital and community nurses expressed a strong need for a better overview of the information exchange between them. Much of this could be both unstructured and undocumented. Earlier studies also point out challenges in relation to information exchange and the information that is relevant and important in the handover (21, 22, 31).

Community nurses find that important information may be lost in the communication between hospital and local authority (19). This finding is similar to findings in our study, which also showed that important information about the patient may be lost in the communications gap between ward nurses in hospital. An earlier study sheds light on the insecurity patients and their families may experience in connection with transitions. It also demonstrates that health personnel may fail to provide information about what the imminent transition entails, and who the patient or their family can contact if necessary after discharge from the hospital (12).

Meleis’ theory, which highlights awareness of the changes that are important for patients and their families as well as nurses in transitions, can shed light on these findings (4, 5). Moreover, findings in our study indicate that the informal and unsystematic exchange of information in telephone calls poses a risk that important information will not be documented, and will then be lost.

Different medical record systems and a lack of mutual access to these may pose a challenge (31). The written exchange of information between the specialist and primary health services takes place via electronic care messages. Brattheim et al. (32) point out that these promote closer cooperation across health levels, but poor-quality messages lead to a need for supplementary oral communication.

The study of Lundereng et al. (21) mentions that nurses were not always confident that the other party had read and understood the message content, and therefore they double-checked by telephone. Access to electronic communication between the medical record systems is discontinued when the patient is discharged from hospital (31).

Our findings also indicate that in some cases the hospital and community nurses were unable to bring out the nuances in an electronic care message in the same way as in an oral exchange. This did not necessarily mean that the messages were inaccurate but that an informal conversation was needed to bring out the nuances in the patient’s situation.

Unclear expectations

Allen (33) describes the nurse’s coordinating role as an invisible function that is not noticed until something fails. This invisible function serves to tie all the loose ends together so that patients and their families experience the various health services as coordinated and coherent (3).

The nurse’s coordinating function is vital in maintaining the quality of care in patient transitions. However, we need to clarify what this involves in terms of tasks and practice. Knowledge of transitions theory can provide a sound framework that enables the nurse to be aware of the critical points in a transition. Moreover, applying the theory can promote the wellbeing and coping skills of the patient and prevent negative impacts on health and illness during transitions (1, 2, 5).

According to Meleis and Trangenstein (1), the nurse has a unique role and key function in helping patients to manage and cope with transitions, partly because they must make the patient and those involved aware of what a transition may entail (4, 5).

The degree of personal involvement in a transition will depend on how aware the patient is of the changes and experiences the transition entails. These depend on the individual and require the nurse to chart what the patient experiences when they are discharged from hospital to home.

The patient pathway in the home may be the solution for the critical points we have identified in this study as it has guidelines for the systematic mapping, coordination and follow-up of the patient (16).

However, it is too early to say if this will serve the purpose. Critical voices claim that the care pathway is a tool suited to the treatment focus of hospitals. They assert that holistic patient pathways cannot be standardised in the same way, since these do not involve a diagnosis but an individual overall health status and function that forms the basis of the local authority’s planning and provision of services (34).

Another challenge, which the Norwegian Cancer Society has highlighted (35), is that the patient pathway in the home is a recommendation that health trusts and local authorities cannot be instructed to use.

The study’s strengths and weaknesses

The focus group interview is an efficient way of collecting qualitative data. Good interaction in the group can produce rich data through an exchange of opinions where the individual must put forward clear arguments to support their views. A weakness may be that some participants may dominate the discussion, whilst others do not make themselves heard (27).

A weakness of the study is that our dataset is associated with a particular geographical area. This could have been avoided by recruiting informants from other hospitals and local authorities in Norway. A third focus group interview with informants from both the primary and specialist health services might have produced a richer dataset. Moreover, as the first author conducted the research in their own field, this may have impacted on the study’s validity.

However, a strength of the study is that the co-moderator is an experienced researcher, and the second author has contributed to the various steps of the analysis process. Systematic text condensation does not require there to be one overarching theme as the analysis cross-cuts individual themes (28). However, as the themes in this study belonged together, they were grouped under one overarching theme.

Conclusion

Nurses in both the specialist and primary health services found that patient transitions from hospital to home were characterised by unsystematic planning, and it was challenging for nurses in their busy workday to gain an overview of the necessary information when preparing for a patient transition.

Both parties had certain expectation of what the other party could or should do in these transitions, but these were not clearly formulated. The community nurses in particular perceived shortcomings in patient transitions. To ensure that the patient was cared for, they compensated for these inadequacies by carrying out tasks that should have been performed in hospital.

Clinical practice should acknowledge that a patient’s needs may change in a different context. The differences in the working situation of nurses in the primary and specialist health services must also be recognised.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the informants who shared their experiences. Without you, this article would not have come to fruition. Thanks also to Bente Ervik, PhD – manager and cancer nurse at the Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, University Hospital of North Norway HF – who shared her knowledge of interview techniques prior to the pilot focus interview, and contributed as a co-moderator in the pilot and focus group interviews.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments