Patients’ perceptions of quality of life in heroin-assisted treatment

Summary

Background: Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) is a type of opioid substitution treatment for patients with a heroin dependency. HAT involves supervised consumption of medically prescribed heroin (diacetylmorphine) twice daily. Nurses follow up patients’ treatment on a day-to-day basis. HAT was established in Norway in 2022 as a five-year pilot project in Bergen and Oslo. Research on quality of life among patients with a substance use disorder has primarily been quantitative. At an international level, patients’ experiences with HAT have been underreported.

Objectives: To gain insight into HAT as a treatment method and its potential implications for patients’ quality of life. This qualitative study is the first in Norway to examine how HAT impacts on patients’ perceived quality of life.

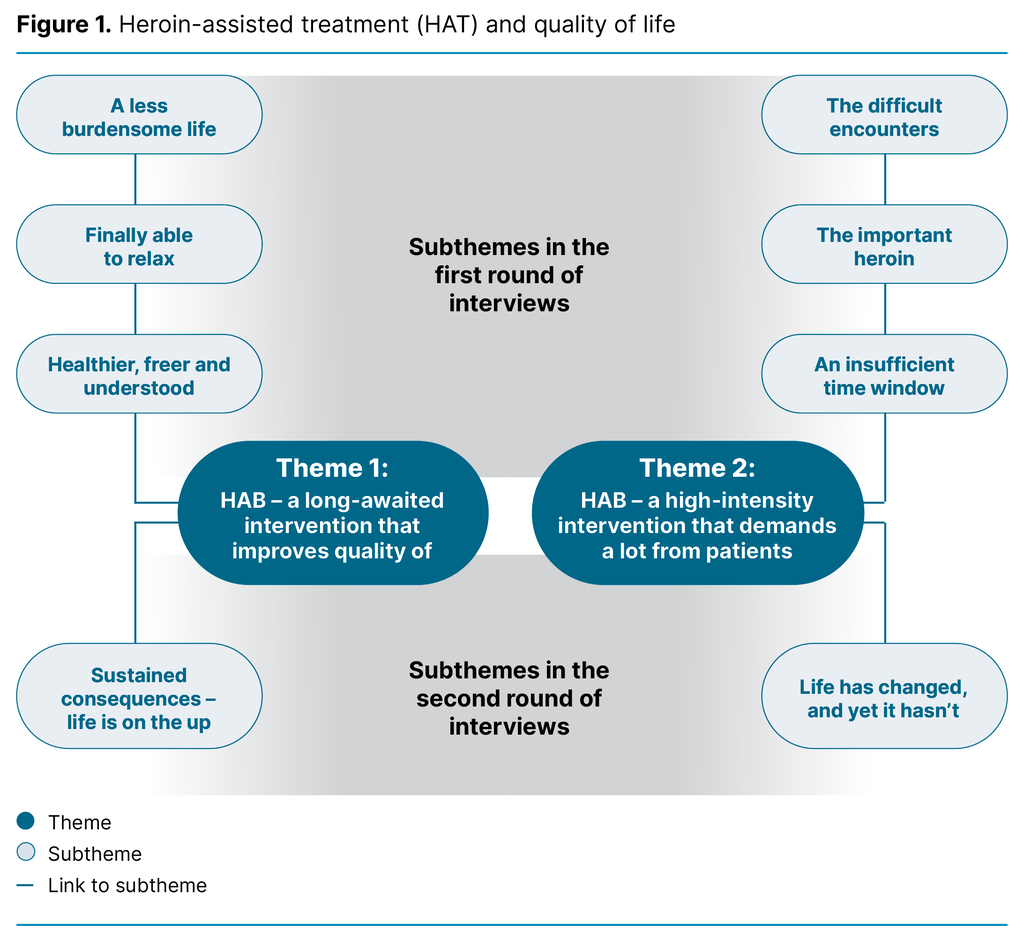

Method: We conducted semi-structured interviews with six HAT patients in Bergen, one month and six months after starting treatment. The data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke. We developed two main themes that capture the key patterns in the data on the patients’ quality of life. The main themes constitute a core idea and are organised around an overarching concept.

Results: After systematically reviewing the data, we identified two main themes. Theme 1, ‘HAT – a long-awaited intervention that improves quality of life’, which addresses the participants’ perceptions of how HAT has improved their lives: access to heroin makes life less stressful, and they feel safer and more stabilised. Theme 2, ‘HAT – a high-intensity intervention that demands a lot from patients’, which highlights the challenges of daily attendance and interactions with staff and other patients at the clinic. Nevertheless, the participants expressed that the benefits of HAT outweigh the drawbacks.

Conclusion: As a stabilising intervention, HAT can help improve patients’ quality of life by reducing the burden associated with heroin dependency. Stable and safe access to medically prescribed heroin means they have more time and money and feel a greater sense of freedom. The treatment programme is challenging, but they believe it is worth the effort. Challenges mentioned by the participants are related to their heroin dependency and could likely be further reduced by recognising the complexity of dependency and increasing the psychosocial support for each patient.

Cite the article

Kyrkjebø-Urheim T, Andersen C, Ellefsen R. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life in heroin-assisted treatment. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(97141):e-97141. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.97141en

Introduction

Opioid dependence is a severe disorder that affects the physical, mental and social aspects of life (1). It is characterised by an inability to regulate the use of substances like heroin despite the adverse consequences (2). People with opioid dependence are more likely to receive disability benefits, and they have a four to seven times higher risk of premature death (3–9). They also report a lower quality of life compared to the general population (10–13).

High overdose figures indicate that people with a substance use disorder (SUD) do not receive adequate help, and in 2023, there were 363 drug-related deaths in Norway (14). Most of these were linked to heroin and other opioids. In the National Overdose Strategy 2019–2022, the Norwegian Directorate of Health introduced measures to prevent lethal overdoses and improve the quality of life for this patient group (15). These measures included better access to opioid agonist treatment (OAT) and the development of heroin-assisted treatment (HAT).

HAT is a five-year pilot project that is being evaluated by the Section for Clinical Addiction Research (RusForsk) at Oslo University Hospital, among others. This study of HAT in Bergen was conducted as a master’s project at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences in collaboration with RusForsk. HAT was launched in Oslo and Bergen in the winter of 2022 as part of the existing OAT provision.

HAT patients attend an outpatient clinic twice daily to take medically prescribed heroin (diacetylmorphine), administered by injection or tablet, as an alternative to other substitution medications. The treatment has a higher intensity than other forms of OAT. Patients are assigned a primary nurse who follows up on their daily treatment. Patients can also receive psychosocial support from a social worker or psychologist at the clinic. The treatment is aimed at patients with opioid dependence who have not had sufficient results from standard OAT (16).

HAT is available in countries such as Denmark, Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands. International research shows that the treatment has a positive, stabilising effect (17, 18), that heroin improves quality of life more effectively than methadone, that the treatment leads to a higher level of satisfaction (12, 19), and that it can reduce the use of illicit heroin (18, 20). However, HAT has been a controversial treatment method both in Norway and other countries.

There are few qualitative studies on quality of life and HAT internationally (21, 22). Considerable quantitative research has been conducted on dependency and patients’ quality of life; however, more qualitative research has been called for that includes the user’s perspective and a subjective approach to quality of life (10, 21, 23). This study contributes to such knowledge.

Objective of the study

The first and second authors worked together on the master’s study on which this article is based. The study was one of the first contributions to research on HAT in a Norwegian context. The aim was to generate knowledge about HAT as a treatment method and its potential impact on the quality of life for patients in Bergen. The research question for the study was as follows:

How do HAT patients feel that the treatment impacts on their quality of life?

‘Quality of life’ has many definitions, but in this article, we focus on it as a subjective psychological phenomenon, defined as mental well-being and an individual’s experience of feeling good (24). A good quality of life is when a person’s conscious cognitive experiences, such as evaluations, thoughts and perceptions, are positive, while negative affective experiences, such as emotional states, indicate a poor quality of life (24).

RusForsk recently published an article addressing patient satisfaction with HAT in Bergen and Oslo (25). The article is based on parts of the same data collected for our study by the first and second authors.

Method

Sample and recruitment

Only ten patients were enrolled in HAT when we began recruiting for the study. We therefore formed a strategic sample from this group, and included the six who gave their consent to participate, made up of an equal number of women and men. The median age of the participants is 43 years.

At the time of recruitment, the second author was employed in the HAT programme. In her professional capacity, she informed the patients about the study, obtained consent and arranged interviews. We will later discuss how this asymmetrical power dynamic may have impacted on the data.

Interviews

The first and second authors each conducted semi-structured, individual interviews with three participants. The interviews were held one month and six months after treatment started. One participant withdrew from treatment and was unable to participate in the second round of interviews, resulting in a total of eleven interviews.

The interview guide was devised by RusForsk, and we included our own questions about quality of life, such as: ‘How does HAT impact on your quality of life?’ The most suitable time and place to conduct the interviews was at the clinic after the participants had taken their dose of medically prescribed heroin, as they would not be experiencing withdrawal symptoms at that point. The interviews lasted between 15 and 60 minutes. Each interviewer made audio recordings of their own interviews and transcribed them verbatim.

Data analysis

The first and second authors carried out reflexive thematic analysis on the qualitative data, as described by Braun and Clarke (26–28). This six-phase analytical method entails creating codes and developing themes from across the dataset. We adopted an inductive approach and sought to develop codes and themes that reflected both the positive and negative aspects of HAT that could impact on the participants’ quality of life.

The focus in this analysis method is on the researcher being reflexive, i.e. subjective, curious and critical of their own preunderstandings. Throughout the process, we discussed how our preunderstandings and experiences from working in the field of substance use could impact on the analysis in the study.

Research ethics considerations

This study was part of RusForsk’s research project, which has been approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK), reference number 195733. The research project has also been approved by the data protection officer at Oslo University Hospital and at Haukeland University Hospital. We adhered to RusForsk’s and Oslo University Hospital’s research protocols for data collection and storage to protect participants’ privacy and ensure secure data management. Pseudonyms are used in excerpts from the interviews.

Results

The thematic diagram (Figure 1) shows the findings of the analysis, setting out two main themes: ‘HAT – a long-awaited intervention that improves quality of life’ and ‘HAT – a high-intensity intervention that demands a lot from patients’. The subthemes from the first round of interviews are shown in the upper part of the diagram, while the subthemes from the second round of interviews are positioned in the lower part.

HAT – a long-awaited intervention that improves quality of life

The first main theme that was constructed from the analysis describes the experiences and feelings in relation to HAT that help to improve the participants’ quality of life. The participants said that they applied to take part in HAT due to their heroin dependency, the offer of free heroin administered legally in a safe environment, and a desire for a better and more stable life. The four subthemes are briefly described below.

The subtheme ‘A less burdensome life’ focuses on the direct consequences of HAT, such as the sense of liberation from the stress and anxiety of looking for their next fix every day. Other consequences include reduced use of illegal substances and less involvement in criminal activities. They also no longer have to fund their heroin use from within an environment that could cause them psychological and physical harm.

These factors in turn led to better finances, improved health and more time in their daily lives. We interpret this finding as an improved life situation that entails a better quality of life:

‘How much easier everyday life became for me after I started here. When I think about it, how much time I actually spend looking for my next fix, and whole days go by just trying to stay well, and that constant search, you know.’ (Tore, first interview)

‘Finally able to relax’ addresses the more indirect consequences of heroin dependency and how it can be all-consuming without proper help. The daily supply of heroin that participants received in HAT gave them a sense of safety and predictability. HAT also gives them a routine and stability in life, where the time they would otherwise have spent looking for their next fix can be used for enjoyable activities. Life becomes more relaxed, leading to an improved quality of life:

‘I just notice how much easier it is to get out now and get things done at home, and I eat more, and yes, I feel a bit more relaxed.’ (Tore, first interview)

‘Healthier, freer and understood’ addresses the indirect emotional consequences of HAT. This subtheme includes the feeling that life has improved, of better self-esteem, of finding more meaning and belonging, of recognising the heroin dependency and feeling freer and healthier. They felt healthier due to the positive effects and minimal adverse effects of the medically prescribed heroin, along with experiencing fewer withdrawal symptoms throughout the day:

‘Things have really only gone in the right direction, or the direction I had hoped. I appreciate being part of this, and yes, as I said, it makes things much better and easier, I’m a bit healthier and more active, and I get things done.’ (Tore, second interview)

‘Sustained consequences – life is on the up’ is the subtheme from the second round of interviews. Shortly after starting HAT, the participants were more focused on the direct consequences of the medically prescribed heroin they were given. After six months, they were more concerned with the implications of HAT for their lives. Most of the positive aspects related to the quality of life that were identified in the first round of interviews continued into the second round.

HAT – a high-intensity intervention that demands a lot from patients

The second main theme that was constructed from the analysis describes experiences and feelings in relation to HAT that may hinder quality of life. Examples of these include encountering other substance users at the HAT clinic, being faced with ignorant attitudes from the staff, and the frequent attendance required. The four subthemes are briefly described below.

‘The difficult encounters’ addresses the interactions with other HAT patients and staff. At the HAT clinic, participants will be in the presence of other substance users, some of whom they may have a bad relationship with. They asked to be separated from other substance users and expressed concern about the inclusion of those who might exploit the programme. They also felt that the staff imposed sanctions and made unreasonable demands. Some of the staff lacked understanding and knowledge about dependency, as well as the effects and motivations behind each patient’s use of heroin:

‘I’m not going to tell them [the staff] if I have a relapse with pills; they can figure it out for themselves. I could get punished for saying something like that. They put you in a position, and on top of that they expect you to manage fine, when the reason I took [another substance] was to top up the dose I had.’ (Lisa, first interview)

‘The important heroin’ refers to the perception that heroin is so essential that the informants prioritise attending the clinic even though the frequency of visits is challenging and prevents them for planning other activities. Many of the informants, particularly those who live far away, find that being so tied to the clinic is exhausting and that it restricts their freedom. Some expected a stronger effect from the medically prescribed heroin:

‘It’s the fact that you have to come here twice, you always have to be thinking about it.’ (Ruth, first interview)

In the subtheme ‘An insufficient time window’, the informants described rigid opening hours that did not align with their needs and rhythms. They expressed a desire to have the option of a third dose of heroin and a meal at the clinic. The HAT clinic in Bergen does not offer either of these, which they found limiting.

‘Life has changed, and yet it hasn’t’ is the subtheme from the second round of interviews. The negative aspects from the first round of interviews were still present after six months of HAT. The informants shared more about how their dependency affected their daily lives, such as use of additional substances to numb unpleasant feelings and painful experiences from life in the drug community, in relation to violence and exploitation. HAT does not address aspects such as this that reduce quality of life. Life is still difficult.

The results show that the informants have both positive and negative affective and cognitive experiences related to HAT. They describe how the medically prescribed heroin makes them feel joyous, euphoric, safe, a sense of belonging and recognised. These are examples of positive affective experiences. They are more satisfied with their lives because HAT gives them stability and routine. They have better self-esteem and feel healthier and freer. These are examples of positive conscious cognitive experiences. The informants also reported that HAT helps reduce negative affective experiences such as anxiety, fatigue, shame and stress.

However, they also found HAT to be exhausting and time-consuming. It involves involuntarily meeting other substance users. These are examples of negative conscious cognitive experiences. Both the positive and negative aspects of HAT highlighted by the informants correspond with results from international studies (21, 22).

Discussion

The results show that medically prescribed heroin is a major, important and somewhat positive part of the informants’ lives. They illustrate the complexity of substance use disorders in the context of heroin use being generally perceived in a one-dimensional negative light and sobriety being idealised. However, the aim of receiving HAT is not sobriety or recovery from dependency, but rather to gain access to medically prescribed heroin and manage the dependency in a responsible manner within the framework of the healthcare system. Nevertheless, as the results show, these frameworks can be perceived as rigid and insufficiently adapted to the patients’ needs.

Quality of life and dependence

Drug use has a powerful effect on the brain’s dopamine release and gives the brain a major boost compared to other natural dopamine-releasing activities. Over time, this can alter the brain’s motivation and reward system, thereby increasing the motivation for further consumption. As a result, the positive affective experience associated with heroin use becomes so intense that it can overshadow most aspects of the lives of individuals with an SUD (7, 29, 30, 31).

When informants cite heroin as the most important aspect of what they perceive as a better quality of life, it should be understood in this context. Access to medically prescribed heroin in HAT also means that informants no longer need to worry about withdrawal symptoms or the stress of funding illegal heroin use.

Medically prescribed heroin in HAT gives an immediate positive affective experience of euphoria and reduces negative cognitive experiences of suffering from withdrawal symptoms and the stress and anxiety associated with looking for the next fix. Both the act of taking heroin itself and the safety and predictability of the HAT clinic supplying them with medically prescribed heroin lead to the perception of a better quality of life. The informants are relieved of the uncertainty and risk of taking illicit heroin, and the use of medically prescribed heroin is monitored and takes place in a safe environment.

The informants also said that, with HAT, heroin use is reframed as medical care as opposed to a criminal act. This can help reduce the shame associated with SUD and increase the feeling that opioid dependency is recognised by the healthcare system and society in general (32).

The informants also highlighted that HAT means they no longer need to seek out the drug community to obtain illicit heroin. This is described as one of the reasons for their improved quality of life. While meeting the physiological need for heroin is important, it seems that this alone is insufficient for them to distance themselves from the drug community.

HAT improves quality of life – real or not?

Treatment for SUD is complex. On the one hand, patients’ physiological dependence must be treated with medication to adjust their tolerance levels and prevent withdrawal symptoms. Meanwhile, the psychosocial aspect of dependency needs a sufficient focus in the treatment process. This group of patients needs help to change behaviour patterns and habits that feed their condition.

The findings of this study are consistent with international quantitative research in which HAT patients are more satisfied with the medication than those receiving other forms of opioid substitution treatment (19).

However, the qualitative interviews provide deeper insight, showing that while patients may be satisfied with the medication, the lack of a comprehensive treatment provision makes it difficult to improve their overall life situation. This point aligns with an international literature review recommending a stronger focus in clinical practice on the quality of life of those receiving treatment for opioid dependency (10).

The informants described how they found the daily attendance exhausting and that it could get in the way of them pursuing enjoyable activities. This can negatively affect their perceptions of quality of life. Self-fulfilment is considered an important aspect of a good quality of life (24, 33). The intensity of HAT seems to limit patients’ opportunities to engage in any activity other than the treatment.

The frequent visits to the HAT clinic mean that the informants involuntarily spend time with other substance users, which can trigger a craving to take drugs to regulate negative emotions. Some informants also feel that the staff do not sufficiently understand their dependency and the effects of heroin. These factors can make it difficult for the informants to avoid feeling shame about their dependency. The shame associated with SUD is often both the cause and effect of substance use (34). There is a risk that the clinic environment perpetuates cravings and feelings of shame.

Stabilisation from a single daily dose of medication, without experiencing the usual high, can also present challenges. The high often serves a purpose beyond its biological and chemical effects, including keeping unpleasant feelings, such as anxiety, shame and guilt, at bay.

As patients develop a tolerance to heroin and stabilise their dosage, they may find that the heroin becomes solely a means of preventing withdrawal symptoms. Negative emotions may not necessarily be suppressed any longer, and the heroin’s utility may decrease. This can make navigating everyday life a challenge that calls for some extra support. The dependency becomes more complex, and treatment must offer something more. HAT as a purely medication-based treatment can lead to an oversimplified view of SUD as a disease. Consequently, this treatment approach may be inadequate for addressing the non-medical needs of patients that are essential for improving their quality of life.

The shift from heroin as an intoxicant to a medicine has significant implications. The psychosocial and social education aspects can be overshadowed by the medical need to control its administration and the assessment of whether it is medically justified.

It is important to remember that this treatment is intended for active users with an opioid dependency who have not had satisfactory results from standard OAT: the most vulnerable and hardest to treat. They cannot be expected to be continuously stabilised, as neither dependency nor stabilisation are a linear process. Staff can better support patients by recognising this reality and reducing their own need for control.

Building relationships, preventing the use of additional substances and addressing other challenges become easier if psychosocial follow-up is emphasised, prioritised and further developed to meet the patients’ complex needs beyond the medical. The nurses’ expertise should also be utilised for effective psychosocial follow-up, as they work most closely with the patients.

Methodological considerations

In this study, we have focused on reflexivity, remaining mindful of how we as researchers have influenced the research process and the results. Three aspects of the project have been particularly important: interviewing informants under the influence of a substance, our experiences as nurses from working in the field of substance use, and the second author’s dual role as both an employee at the HAT clinic and a researcher.

The interview situation and interviewing active substance users who could be considered intoxicated, was no easy task in terms of the ideal qualitative research interview. We encountered reluctance, polite rejection, hypersensitivity and a lack of both interest and experience in discussing life. It was often difficult to decipher what was being said. These factors raise questions about the validity and quality of the data.

We believe the data provide important insights and are representative of the informants’ reality. When researching this patient group, it is also necessary to consider that the group is under the influence of the substance they are dependent on. We treated the informants differently from interview subjects who are not part of a marginalised group or under the influence of substances; we would have challenged the latter group more.

It is reasonable to question whether the informants felt pressured into participating in the study. The second author had a dual role as an employee at the HAT clinic and a researcher, and was also the one who provided information, obtained consent and arranged the interviews. The participants were told that participation and the information they provided in interviews would not affect their treatment. Nevertheless, they may have consciously or subconsciously wanted to make a good impression on the second author.

They may also have presented HAT in a more positive than negative light because they hoped that it would become an established provision after the pilot project period. These factors, along with the possibility that the data may not adequately represent HAT in Oslo, should be considered when evaluating the study’s data and results. Nevertheless, the study provides important and unique insights into how HAT impacts on patients’ quality of life.

Conclusion

The study’s results show that HAT has a positive impact on the informants’ perceived quality of life, particularly in terms of the access to medically prescribed heroin and because they no longer need to spend time and effort on looking for their next fix. However, several aspects of HAT could be improved to better meet the patients’ needs. This relates to the fact that HAT in Bergen is not equipped to facilitate a comprehensive treatment provision, where relationship-building, social education and psychosocial support are central.

There are indications that HAT in Oslo is better structured for a comprehensive treatment provision (25). Better utilisation of nurses’ expertise in these areas in HAT in Bergen would be beneficial.

However, the positive aspects of HAT outweigh the negative ones for the patients. Furthermore, HAT can help reduce the stigma and shame that this group experiences through recognition and validation of the opioid dependency and use. When the administration of heroin shifts from the streets to the clinic, use becomes safer, and the number of lethal overdoses can be reduced.

One of the goals of HAT is to improve participants’ quality of life. Overall, HAT is an important initiative for enhancing the quality of life for this group. However, if HAT becomes too medicalised, it could result in patients merely functioning, without necessarily achieving the important changes that are needed to improve their life.

We have identified potential for improvement in HAT in Bergen. We believe that HAT’s mandate and objectives need to be more clearly defined. This would allow for an evaluation of whether and how HAT in Bergen can be further adapted to patients’ needs and to a holistic approach for each participant. This would enhance the patients’ quality of life and better equip them to make positive changes in their lives.

Conflicts of interest

During the study, Christina Dahl Andersen was employed in a 60% position in the heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) programme.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments