Boys’ reflections on body image – a qualitative study

Summary

Background: Adolescents feel that there is a strong focus on their body and appearance. They describe feeling pressure to have a body that conforms to societal ideals. Understanding adolescents’ relationship with their body and appearance is crucial for health-promoting and preventive measures. Previous research has largely focused on girls in this context.

Objective: The aim of the study was to explore boys’ reflections on body image.

Method: Employing a qualitative, descriptive method, we conducted nine semi-structured individual interviews with boys aged 16–19 in a city in Norway. The data were analysed using a stepwise inductive-deductive approach, which generated seven code groups. These codes were subsequently condensed into three concepts.

Results: In the analysis, we identified three concepts that described the boys’ reflections: 1) Own body and the ideal body, 2) The importance of the ideal body and 3) Body pressure or motivation. The participants were generally satisfied with their bodies. Boys at a more advanced stage of puberty expressed greater satisfaction with their bodies than those in an earlier stage. The ideal body was a positive identity marker for the boys. Most participants had a negative view of body pressure, but a few considered it a motivating force for exercising.

Conclusion: A body that aligns with societal ideals is positively associated with and important for social recognition, belonging and respect. Body pressure was a common experience among the participants. The study shows that late onset of puberty can make adolescents more vulnerable and prone to body dissatisfaction. This highlights the need for targeted, preventive efforts, with a focus on identity and self-worth in the prepubertal phase.

Cite the article

Hansen I, Nordhagen L, Leonhardt M. Boys’ reflections on body image – a qualitative study. Sykepleien Forskning. 2024;19(95340):e-95340. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2024.95340en

Introduction

In recent years, the subject of ‘boys and body image’ has been regularly debated in the media (1–3). In their own life stories, adolescents describe a desire and struggle to have a body that aligns with societal ideals, which favour a slim but muscular, sculpted and well-proportioned body (3–7).

The proliferation of social media exposes adolescents to gender-specific advertising that portrays a one-dimensional view of the body and appearance. Nearly half of all those in Norway aged 13–18 have been targeted by advertising on how to lose weight or gain muscle (8).

The annual Ungdata survey of youth in Norway has shown that adolescents experience significant pressure in relation to body and appearance, academic performance, athletic prowess and social media (9). Significant pressure in relation to body and appearance was reported by 25% of girls and 23% of boys (9). They described the body pressure and school-related pressure as exhausting and challenging (5, 7, 10).

Girls as well as boys experience a large discrepancy between their own body and the ideal body, which can further reinforce body dissatisfaction and body pressure (5, 11, 12). Body pressure is defined as the feeling that the body should look a certain way (13). On social media, influencers and fitness idols describe exercise and diet methods that will supposedly help to achieve these ideals (14–16).

In the Norwegian living conditions survey on sports and outdoor activities, 58% of the population aged 16 and over reported that they exercise or engage in physical activity several times a week. The younger generation primarily exercised to improve their appearance, while the older generation exercised to improve their health, get fresh air and experience nature (17).

In recent years, considerable research has been conducted, both nationally and internationally, on adolescents’ relationship with their bodies. Most studies have been quantitative and have found high levels of body dissatisfaction and body pressure among girls (4, 10, 18). Previous research and media articles have been dominated by girls’ experiences and perceptions (4, 5, 19).

Studies of boys show that a significant proportion report body dissatisfaction, mainly related to body shape, muscle tone and muscle mass (4, 11, 14). Just as many boys as girls struggle with disordered eating and exercise behaviours, body pressure and body dissatisfaction, but far fewer boys seek help from the school health service or other first-line services (34).

Meanwhile, boys have been under-represented in relevant research, and their experiences with body pressure and body dissatisfaction have been under-communicated and taboo (20–22). The purpose of this study was therefore to explore boys’ reflections on body image. This knowledge will inform the development of a more attractive health service provision for boys and young men.

Method

Our study is qualitative with a descriptive design. We conducted nine semi-structured, individual in-depth interviews.

Recruitment and sample

We asked seven public health nurses in upper secondary schools in a city in Norway for assistance in recruiting informants. Three declined due to time constraints. The remaining four obtained consent from their respective schools. Information about the study was distributed to several classes and pupils. Those who wanted to participate were encouraged to get in touch.

Six informants were recruited. Three more were recruited via the snowball method, where informants who have been interviewed ask their fellow pupils to participate in the study. This method ensures motivated informants and is time-efficient (23).

Pupils who needed an interpreter or follow-up by a school psychologist or public health nurse were excluded. This was to ensure that language barriers or additional personal stresses did not influence the responses.

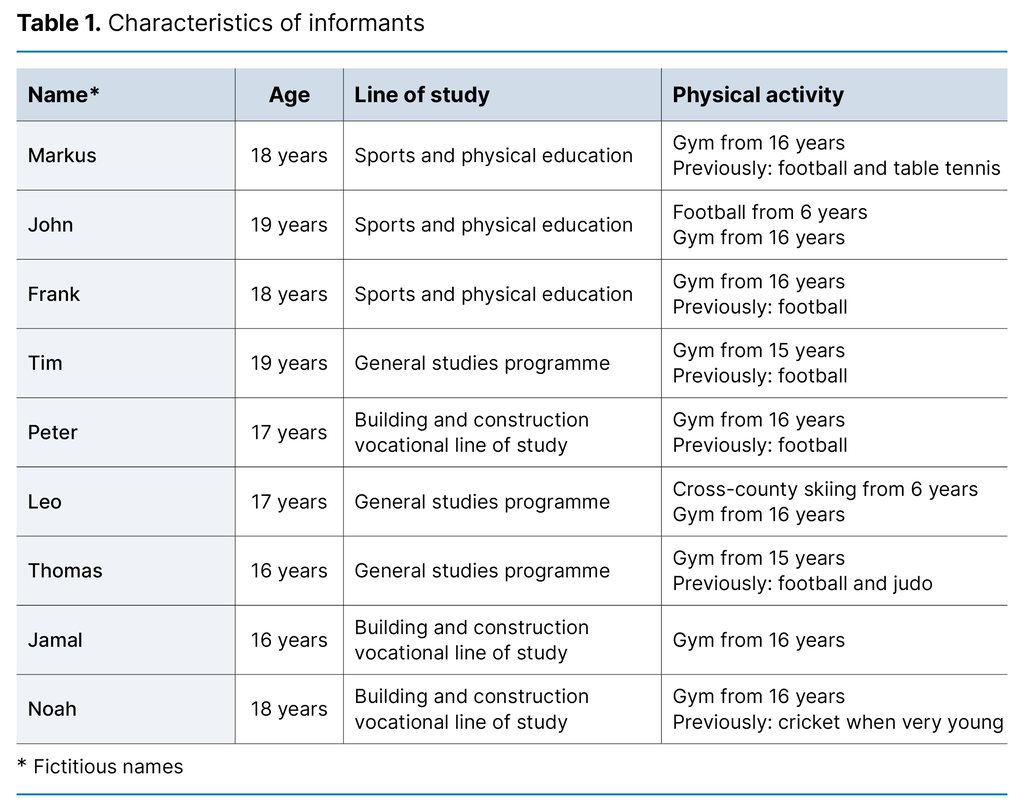

The participants signed a consent form, and the interviews were arranged. The final sample consisted of nine boys aged 16–19 from four upper secondary schools. Three of the informants were in the general studies programme, three were studying sports and physical education, and three were taking the building and construction vocational line of study (Table 1).

Data collection

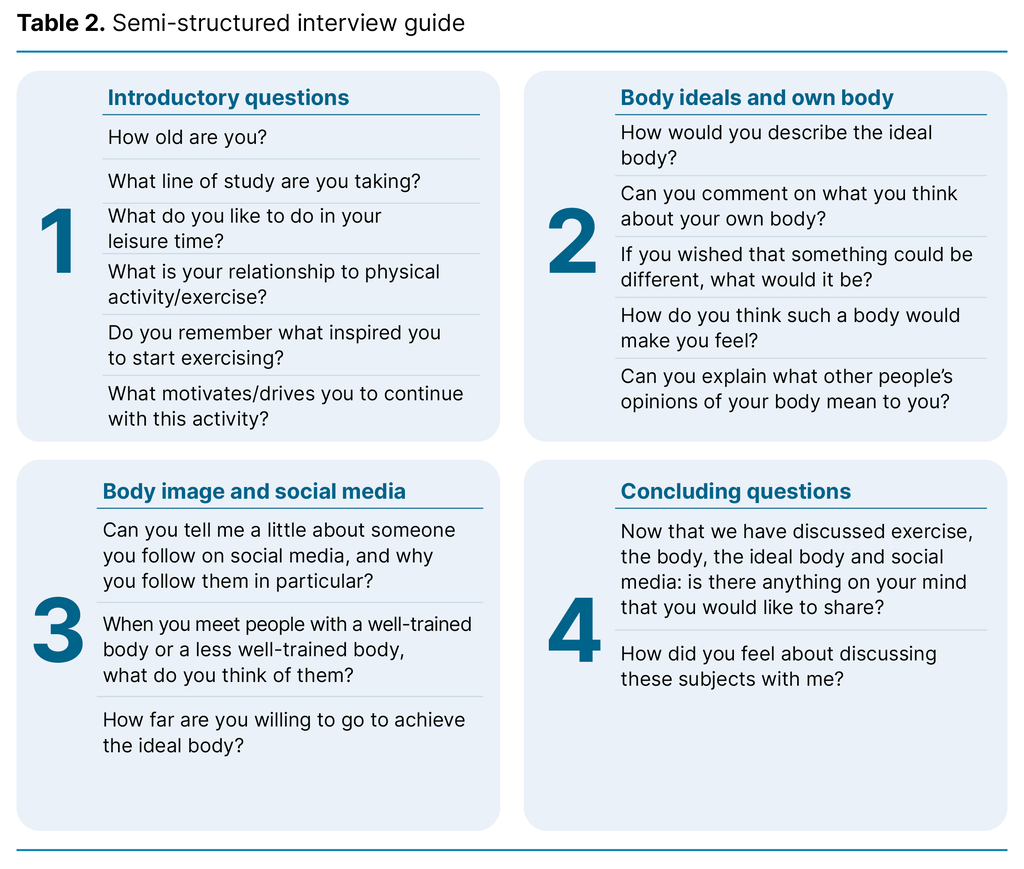

We conducted the interviews in November 2019 with the help of a semi-structured interview guide that had been adjusted slightly following quality assurance in a pilot study. The interview guide consisted of introductory short-answer questions followed by more probing open-ended questions for reflection (Table 2). The order of the questions varied according to the development and dynamics of the conversations.

The interviews were conducted during school hours in specially arranged, sound-insulated interview rooms to prevent distractions. The interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. We recorded the conversations and transcribed them verbatim.

Data analysis

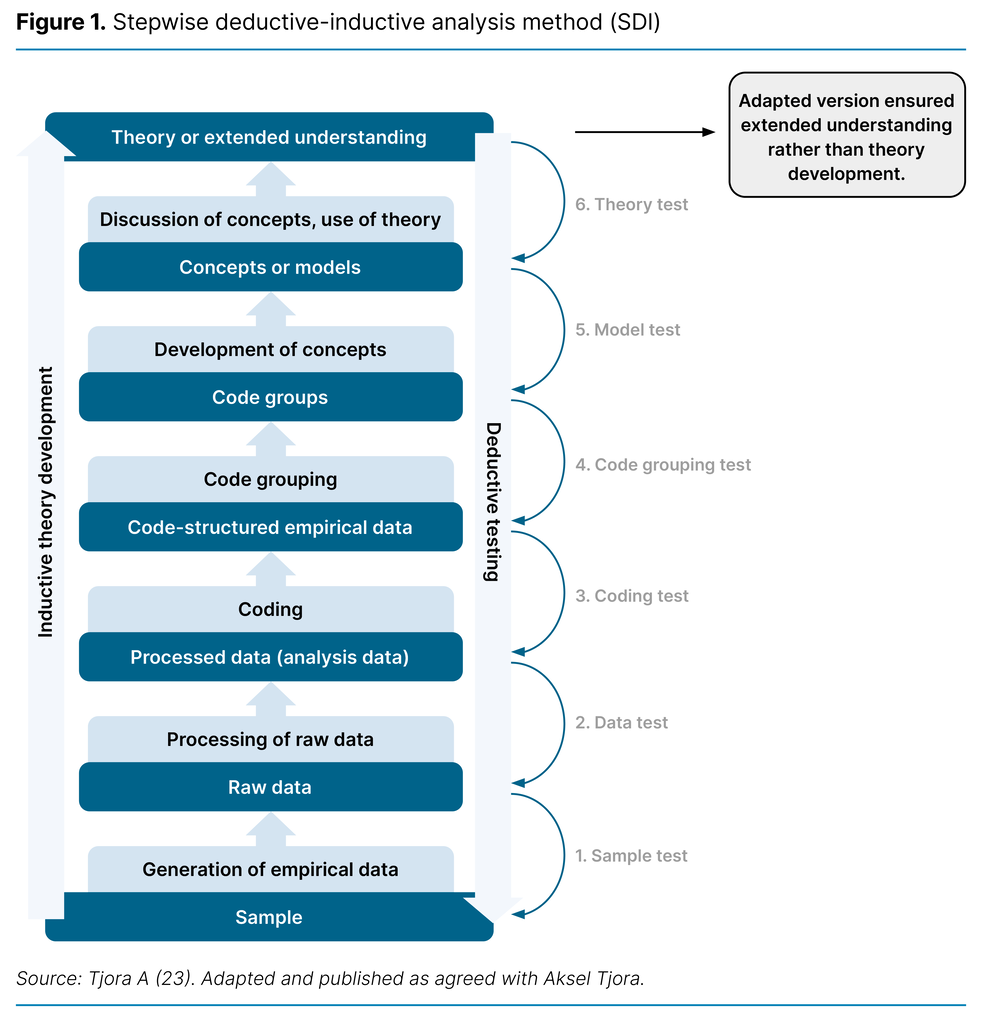

The data were analysed using the stepwise deductive-inductive method (SDI) (23) (Figure 1).

The study followed the first four steps of the model: generating data, processing raw data through coding, categorising codes and developing concepts. The study had a limited scope and it was not therefore relevant to develop theory. We instead used an adapted version of the model. Rather than theory development, our goal was to gain a new and expanded understanding of the subject.

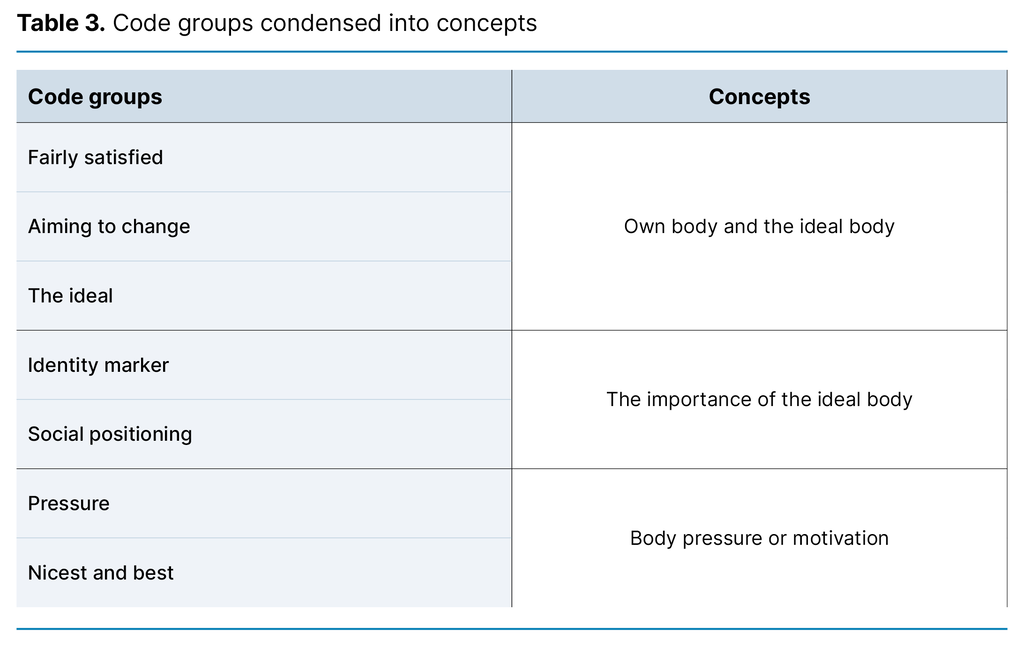

The raw data resulted in 197 codes, which were analysed in various steps, condensed and categorised into seven code groups. These were further condensed to three main thematic categories, also referred to as concepts (Table 3). In the analysis, we identified recurring patterns, and interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved.

Ethical considerations

The study was reported to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), now called Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number 419077). Informants were recruited on a voluntary basis and provided written informed consent. The data collected were anonymised.

Results

We identified three concepts through the analysis: 1) Own body and the ideal body, 2) The importance of the ideal body and 3) Body pressure or motivation.

Own body and the ideal body

The informants described their own body and appearance as ‘fine’, ‘okay’ and ‘adequate’, followed by specific wishes for change:

‘[…] but I wish I was a bit taller’ (Peter), ‘I want to broaden my shoulders’ (Thomas), and ‘I need to work on my thighs’ (Noah).

The informants mentioned height, shoulder width and a well-developed upper body as factors that contribute to satisfaction. Informants in a more advanced stage of puberty were more positive in their descriptions than those in an earlier stage.

The informants with late onset of puberty considered their development to be delayed or stagnant, and they became more dissatisfied as the height and muscles of their peers increased. However, they were optimistic about how they would develop based on their understanding of genetics and typical developmental patterns. The majority referred to the ideal body as ‘the dream body’, and they described it in the same way:

‘Starting under the head; the shoulders should be quite broad. The collarbone should be pronounced, you should have large biceps and triceps, and not too thin forearms, preferably with visible veins on the arms. And you should also have wings, a broad back, a six-pack and fairly large calves’ (Leo).

The informants described the ideal body as athletic, slim, sculpted and ‘properly masculine’. Several informants referred to the American actor and bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger when describing the dream body: ‘I think all boys my age dream of looking like Arnold Schwarzenegger’ (Markus).

All informants emphasised the importance of balance and moderation when it came to muscle growth and muscle appearance. A body that is too big or too muscular had a strong negative connotation and was referred to as ‘unsavoury’ and ‘juiced up’. They referred to people with such an appearance as ‘stupid’ or ‘not very smart’.

Half of the informants associated an untrained body with characteristics such as irresponsibility, laziness and/or psychological and social insecurity: ‘He has little self-control, he’s not as disciplined and doesn’t work as hard and things like that. Maybe he struggles mentally or socially with friends. He’s probably hanging out in the wrong environment’ (Jamal).

The remainder described an untrained body through the person’s interests: ‘They probably have other interests and don’t care about exercise’ (Leo).

The importance of the ideal body

The informants described a well-trained and muscular body as a positive identity marker that reflects desired personal attributes such as hard-working, dedicated and disciplined: ‘He takes a lot of responsibility, because it takes a lot to get a nice body’ and ‘You’re seen as more successful’ (Tim).

The informants felt that body and appearance were important for first impressions: ‘When you meet new people, new boys, you introduce yourself by way of your appearance. Being big and strong gives you a certain status’ (John).

However, several informants discuss this attention in a negative light: ‘You get scanned, stared at in the canteen. It’s a bit stressful’ (Markus).

The informants said that the ideal body ensures recognition and respect from others: ‘The perfect body means that many people notice me, look up to me and like me. The body gives me status’ (Tim). However, there was competition between the boys: ‘All my mates work out, so there’s a bit of competition, yeah, I have to catch up if they get bigger than me’ (Frank).

The informants also emphasised that the body was crucial for attracting attention from girls: ‘A fit body gets a fit lady’. All assumed that an attractive appearance would improve their options and increase their chances of getting a girlfriend.

According to the informants, body and appearance were important for social positioning. They expressed it as ‘a gateway to desirable social arenas and environments’.

One informant linked appearance to future employment: ‘A well-trained person knows how to stay in control, so can have control over others in a work context’ (Frank). More than half of the informants drew a parallel between the ideal body and success: ‘Look around you; there are more good-looking successful business leaders than ugly ones. That’s just how it is’ (Leo).

Two informants related the dream body and a muscular appearance to respect and security: ‘I train to get muscles, you know, you have to be big to be able to thrash someone’ (Jamal). Both had described challenging times as a child. The three informants in vocational education linked the desire for a strong, muscular body to the need for muscle strength to meet the physical demands of future employment.

Body pressure or motivation

In the body image reflections, the term ‘body pressure’ was used repeatedly: ‘There’s definitely body pressure. Having a big, muscular body with a six-pack and attractive ab crack and all that’ (Thomas).

Body pressure was mainly described as a negative feeling: ‘There’s a bit of pressure. I have to catch up with those who’ve gotten bigger than me, and it gets a bit stressful’ (Tim).

They described the desire for progress and quick results as stressful. ‘I can definitely say that I start to really depend on making progress and getting results. It’s exhausting – not so much physically, but more mentally’ (Frank).

Despite their stress, they did not consider it relevant to contact first-line services to discuss the issue or obtain advice. This kind of help was viewed in a negative light: ‘Boys want to be manly, and it’s not manly to talk about your feelings’ and ‘Boys have to be able to fix their own problems’ (Jamal).

Meanwhile, a third of the informants thought that body pressure was somewhat positive as it leads to a healthier diet, regular exercise and social interaction at the gym: ‘I think everyone can feel body pressure at times, and that’s healthy. Yeah, it’s healthier to be thin and do exercise than to be so overweight that you can’t walk straight’ (Frank).

The positive effect of exercise on sleep quality and the sense of well-being was also discussed. Several described the gym as an important and informal social arena that promotes a sense of belonging.

All informants did strength training and cited increasing muscle growth and altering their appearance as the most motivating factors for the training:

‘I train to look good, and the health benefit is less important. I don’t care too much about my health, I’m young, I go out drinking, and I’ve had periods where I’m smoking and things like that’ (Markus).

Exercise was seen as a necessary measure in response to body pressure. It was also described as a positive activity that gives structure to daily life:

‘With the training, I go there and have peace, and it gives me something to do every day instead of hanging around doing stupid things’ (Jamal).

They also described diet and nutrition as crucial to achieving the body ideal. The level of knowledge varied and was mainly based on advice and recommendations from friends, older siblings, and influencers and sports idols on social media. All informants except one had used or were currently using dietary supplements regularly. They differentiated between legal and illegal substances. Two-thirds of the informants were strongly opposed to the use of, for example, anabolic androgenic steroids due to a fear of side effects: ‘I will never resort to pills and doping. Dietary supplements and shakes are things I’ve tried and will definitely try again’ (Noah).

Some had a more liberal or ambiguous attitude towards doping.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to explore boys’ reflections on body image. We identified three concepts ‘Own body and the ideal body’, ‘The importance of the ideal body’ and ‘Body pressure or motivation’, and discuss the topic based on these.

The informants were satisfied with their own body and appearance. All of them had specific goals for how they wanted their body to look. The ideal body can be understood as a positive identity marker that reflects personal characteristics. A body that aligns with societal ideals was considered important for attracting a potential girlfriend. What was even more important was recognition by their peers, respect, and social belonging and positioning.

The dream body

The informants’ body image reflections were consistent, and they used general terms and emotionally neutral words like ‘okay’. Their descriptions of the ideal body aligned with the current male body ideal, which is slim, muscular, sculpted and capable of sustained physical performance. These findings are consistent with research reports from Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, which also found that young boys aspired to a masculine, muscular physique that aligns with the ideals of Western culture, characterised by broad shoulders, a narrower waist, and a well-proportioned body with a low fat percentage (4, 10, 19, 24).

Body ideals are constantly changing (12, 25), and have recently shifted towards a mesomorphic ideal, which values well-defined muscles, a well-developed chest and shoulder area and a narrow waist and hip area. A smaller proportion of body fat is desired than before, and adolescents’ role models and idols have become both thinner and stronger over the last 30 years (1, 14, 16, 26).

A balance in muscle growth and body appearance is favoured. A body that deviates from this by being too large or too muscular is viewed in a negative light and associated with negative personal characteristics by the informants. Sæle refers to deviations from body ideals as ‘the shame of our time’ (27). Research from the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom found that an overly large and muscular body is associated with self-absorption, lower intelligence and low education, and is not compatible with a prestigious job (4, 11, 14, 28).

In this study, the associations with a less well-trained body were less negative and were attributed to these people having other interests or being lazy or insecure. Boys at an early stage of puberty were less satisfied with their bodies than boys at a more advanced stage. International research findings consistently demonstrate that many boys are dissatisfied with their appearance due to insufficient height and muscle growth in relation to their perception of the dream body (21, 24, 29).

Other research found similar results and showed that early onset of puberty leads to greater satisfaction than later onset. Overall, puberty takes boys closer to their dream body through the increase in muscle mass (5, 10). This highlights the importance of covering topics such as normal development and body dissatisfaction in puberty education in primary and lower secondary schools.

Body and appearance as identity markers

The informants referred to the body as an important identity marker that reflects desirable and coveted personal characteristics such as hard-working, dedicated, goal-oriented and disciplined. This perception is supported by other research, which shows that an attractive body and appearance is a reflection of personal characteristics (26, 28, 30, 31).

The pursuit of the dream body can be understood in terms of hegemonic masculinity and the male ideal (26, 32). Hegemonic masculinity is described as a practice in which a social elite sets the standards and norms for the prevailing ideals (26, 28, 29, 32). The elite contribute to, legitimise and reproduce the social relations and trends that perpetuate the dominance of certain men over other men. Body and appearance function as symbolic capital and a gateway to desirable social environments (26, 28, 29, 31).

The informants’ perceptions of the dream body align with this hegemonic male ideal, where the body provides access to desirable and coveted high-status environments. Nielsen describes today’s body ideal as far more hegemonic and homogenised, with girls placing the emphasis on aesthetic aspects of the body, while boys are more concerned with the functional aspects, such as strength and sporting prowess (33).

In our survey, a strong body is also described as important for gaining respect and remaining safe in childhood. A strong body signals physical superiority. The informants in the building and construction vocational line of study also mentioned that muscle strength is important for their future careers in manual labour.

The informants said that body and appearance were crucial for making a good first impression. People are weighed up, ranked and positioned socially based on their body and appearance after just a few seconds of observation. An attractive exterior helps secure the desired positioning and recognition from friends, acquaintances and potential girlfriends. These findings are consistent with other research, which emphasises the value of recognition by friends as motivation for achieving the dream body (4, 31).

The informants in our study said that trying to make a good first impression was stressful and exhausting, leading to additional pressure. According to Sæle, when body shape is perceived as reflecting certain character traits in a person, body pressure will also be greater and more complex (12, 27, 31).

Negative associations concerning the body and appearance

All informants had experienced body pressure. National and international research confirms a high prevalence of body pressure among adolescents and young adults (10, 18, 20). Body pressure is described in our study and others as a negative feeling characterised by low mood, dispiritedness, as well as pressure and stress related to progress and changes in body-related behaviours (6, 14, 20).

Seeking help from first-line services was rarely considered and was described as unmasculine and unmanly. Hargreaves and Tiggemann suggest that this is because boys are experiencing body dissatisfaction whilst also contending with a social taboo against expressing emotions (1). However, previous research shows that good access to and positive interactions with public health nurses and first-line services increase the likelihood of boys subsequently making contact if they are having problems (34). It is therefore important that the public health nurse is present at the school, where regular meeting points such as group sessions and themed gatherings are a key priority throughout primary and lower secondary education.

The informants’ widespread use of dietary supplements can be partly a result of the desire for quick results, reading advice and recommendations on social media, and accessibility. Their reason for not using doping agents was a fear of side effects. However, informants who followed strict exercising and diet regimes seemed to have an ambiguous attitude towards doping.

Eik-Nes found that young men with a strong focus on building muscle are four times as likely to resort to muscle-building supplements, both legal and illegal. Twenty-two per cent reported such use in the past year (10, 14, 30). This highlights the health risks faced by the target group in this study.

Other research points to how public health nurses play a key role in providing new and up-to-date information on the topic as part of their preventive efforts. This can help change and correct adolescents’ assumptions, which may be based on poor knowledge (34).

Strengths and limitations

It is a strength of the study that the informants represent a heterogeneous group in terms of ethnicity, line of study and socio-economic background. The target group, boys aged 16–19, is under-represented in other research compared to girls (5, 10, 20). This strengthens the study’s relevance. The results align with other national and international research (4, 24, 35) and can therefore provide insight into boys’ reflections on body image. Due to the small sample size, the results cannot be generalised.

Conclusion

The informants were generally satisfied with their own body and appearance. Their descriptions of the ideal body were consistent. They considered body and appearance to be important identity markers that were important for recognition and social belonging. Body pressure was a common experience that mainly had a negative association. However, some informants found that body pressure motivated and disciplined them, leading them to make choices that had positive health effects.

The study shows that the informants’ onset of puberty and pubertal development impacted on their degree of satisfaction with their body. It also shows how the masculine ideal is favoured and how the desire for the ideal body is related to expectations and hopes for recognition, respect, social positioning and future employment. This knowledge is important in the health promotion and prevention efforts aimed at pubescent boys.

Our findings highlight the need for access in schools to a public health nurse who can educate groups about puberty development, body pressure, body dissatisfaction, exercise, muscle growth and dietary supplements. This could help make the school health service more appealing for boys.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the informants, the public health nurses who facilitated the study, and the school for its positive attitude.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments