Home visits by midwives in the early postnatal period

The postnatal period is a vulnerable time that involves reorientation and new experiences. Early visits by a midwife may therefore help enhance the women’s perception of coping.

Background: Postnatal care has changed over the years. The period spent in the maternity ward has gradually been reduced from five to six days to approximately two days. According to health policy, women’s and their families’ experience of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity should be coherent and holistic and provide a sense of security.

Objectives: The aim of the study is to shed light on women's experiences with home visits by a local midwife in the early postnatal period.

Method: The study is qualitative. We conducted nine semi-structured individual interviews. We analysed data by using a qualitative content analysis inspired by hermeneutic interpretation and a systematic condensation of text. The study is based on the theory of health promotion, empowerment, coping, autonomy and the relationship between the midwife and the mother.

Main results: Three main categories describe the women’s experiences:

- having control themselves,

- knowledge and support, and

- continuity and relationship with the midwife.

Conclusion: This study indicates that home visits by local midwives may contribute to women being able to cope with the new circumstances in their lives. Being able to meet women’s individual needs seems to enhance empowerment. Midwives and health visitors have different skills that can complement each other and contribute to promoting health in the postpartum period.

Postnatal care has gradually changed over recent years. Previously, the mother and child would spend five or six days in the maternity ward after a normal birth. Now, they generally go home after one or two days, depending on the woman’s health condition (1). The programme for follow-up in the early postnatal period has not been organised to keep pace with these changes. Most pregnant women are followed up by a midwife and doctor in the municipality throughout the pregnancy and give birth in a hospital with the assistance of a midwife employed at the hospital. The woman then moves to a maternity hotel or ward, where she meets other midwives whom she does not know from before.

The health visitor is usually the first person to establish contact with the woman after her return home, seven to fourteen days after the birth. The postnatal period is a vulnerable time of reorientation and new experiences, during which most women may feel a need for information and support. As a result of the pregnancy and birth, the bodily, mental and social changes may represent challenges for the women concerned (2, 3).

Guidelines for postnatal care

The national professional guidelines for postnatal care were published in 2014 to help ensure appropriate and predictable postnatal care. The municipalities provide maternity services that vary in scope and content, and the Board of Health Supervision has pointed out that the time elapsing from the women’s discharge from hospital until they contact the public health centre represents a critical period (1). The Coordination Reform provides instructions for more effort in health promotion and disease prevention. The reform proposes to bestow a key role on the municipal midwife services in the follow-up of mother and child during the first days after birth (4).

The objective of postnatal care is to help the woman establish a better sense of coping and enable her to take charge of her new life situation to the greatest possible extent, in the best interests of herself and her family (1). The midwife and the health visitor possess different skills, but in their follow-up in the early postnatal period their focus in overlapping. The national professional guidelines for postnatal care recommend that both of them undertake home visits (1).

Before the publication of the national professional guidelines for postnatal care, only very few women were visited at home by the midwife immediately after giving birth, since home visits were not included in the tasks of municipal midwives. At the time of writing, only a few municipalities have made provisions for early home visits by a midwife, and there are few studies available of postnatal care practices in Norway (1, 5).

The importance of home visits

Searches for previous research on this topic show that some studies investigate postnatal care in hospitals, while others focus on women and post-partum depression. A number of studies conclude that home visits by a midwife are important. These conclusions are based on investigations of the differences between provision of postnatal care in hospitals and in the home (6, 7), women’s experience of early discharge (8) and parents’ perception of relational continuity when midwifery students provided follow-up during the antenatal, perinatal and postnatal period (9). This study details women’s perceptions and experiences with home visits by a municipal midwife immediately after being discharged following childbirth.

Our research questions are the following:

- What could be the importance of early visits by a midwife with regard to the woman’s perception of coping in her new life situation?

- How can the midwife help in accommodating the woman’s needs in the context of home visits?

- What significance does it have for the woman that the home visit is undertaken by a midwife?

The study is based on theories of empowerment, in the sense of having as much control as possible over issues that may affect personal health. The study emphasised co-determination, redistribution of power and recognition of the woman’s competence in relation to herself (11). The correlation between relational work, perception of coping and autonomy can be regarded as fundamental for health promotion.

Method

The research design is descriptive, with some explorative elements. We chose to use a qualitative methodology to elucidate the research question (12, 13).

We conducted nine semi-structured individual interviews. The interview guide focused on the woman’s perception of her new life situation, the experience of coping in the early postnatal period, perceptions and experiences associated with the home visit by a midwife and the relationship to the midwife.

Regional committees for medical and health research ethics (REC) have determined that the study falls outside of their mandate (reference number 2013/1140 A). The study has been reported to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) (project number 34872) and has been implemented in compliance with guidelines for research ethics (14).

Participants

Since the first author was familiar with the field, she contacted the director of the health services and midwives in the three municipalities that conducted projects on early home visits by a midwife. Most of the visits were undertaken by the same midwife. The women were recruited through convenience sampling (15). The first author requested the municipal midwives to recruit participants consecutively after having undertaken the visit, in order to avoid selective recruitment. All the women who were asked consented to participate in the study.

The inclusion criteria were the following: a healthy child born at full term, home visit by a midwife from one to six days after birth, Norwegian-speaking, and the participation should not represent an undue burden. The participants included six primiparous and three multiparous women. The home visits were undertaken by four different midwives.

Data collection

The first author, who had no previous knowledge of the women involved, was responsible for the collection of data. She interviewed the women in their homes in the period from November 2013 to January 2014. Only the mother and child were present during the interviews, which lasted for an average of one hour. The interviews were recorded on an audio device and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

We analysed the data with inspiration from hermeneutic content interpretation and systematic text condensation (12, 16). The systematic procedure for text condensation helped achieve an appropriate handling of the large amount of text. In addition, the principles for hermeneutic content interpretation helped elicit valid interpretations in a hermeneutic perspective. This perspective implies that any interpretation depends on the prior understanding on which it is based (12).

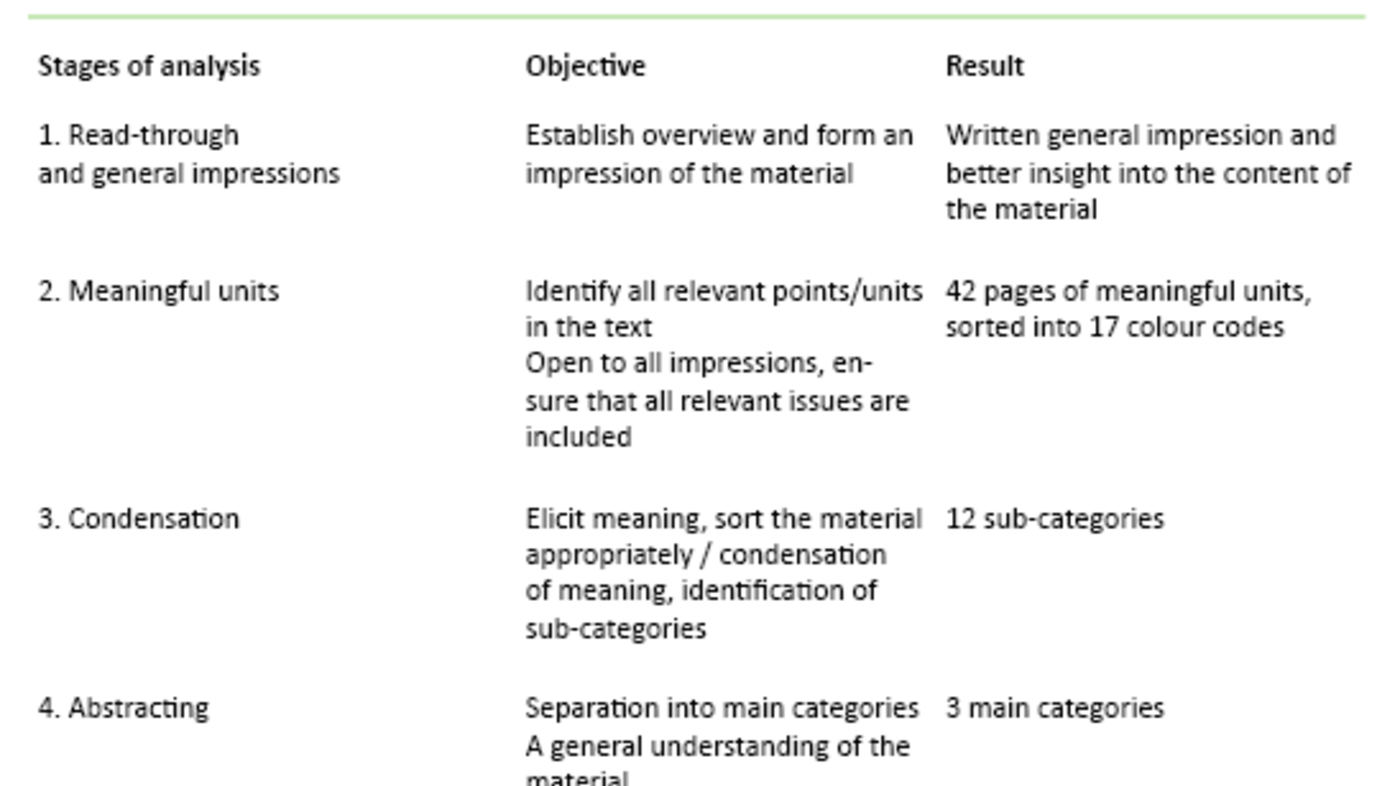

Table 1 shows the four stages of the analysis process.

The first author repeatedly read through the entire material. She made notes of reflections and ideas along the way, before writing down the general impression. The condensation took place in an iterative process that involved all the authors, back and forth between the research questions, general impressions and units of meaning. The abstracting took place in the same way. Research questions, general impressions and sub-categories were assessed in light of each other until the categorisation became meaningful on the basis of findings and research questions. During the analysis process we focused on being aware of our preconceptions, using notes and discussions as an aid, in order to ensure valid interpretations.

Results

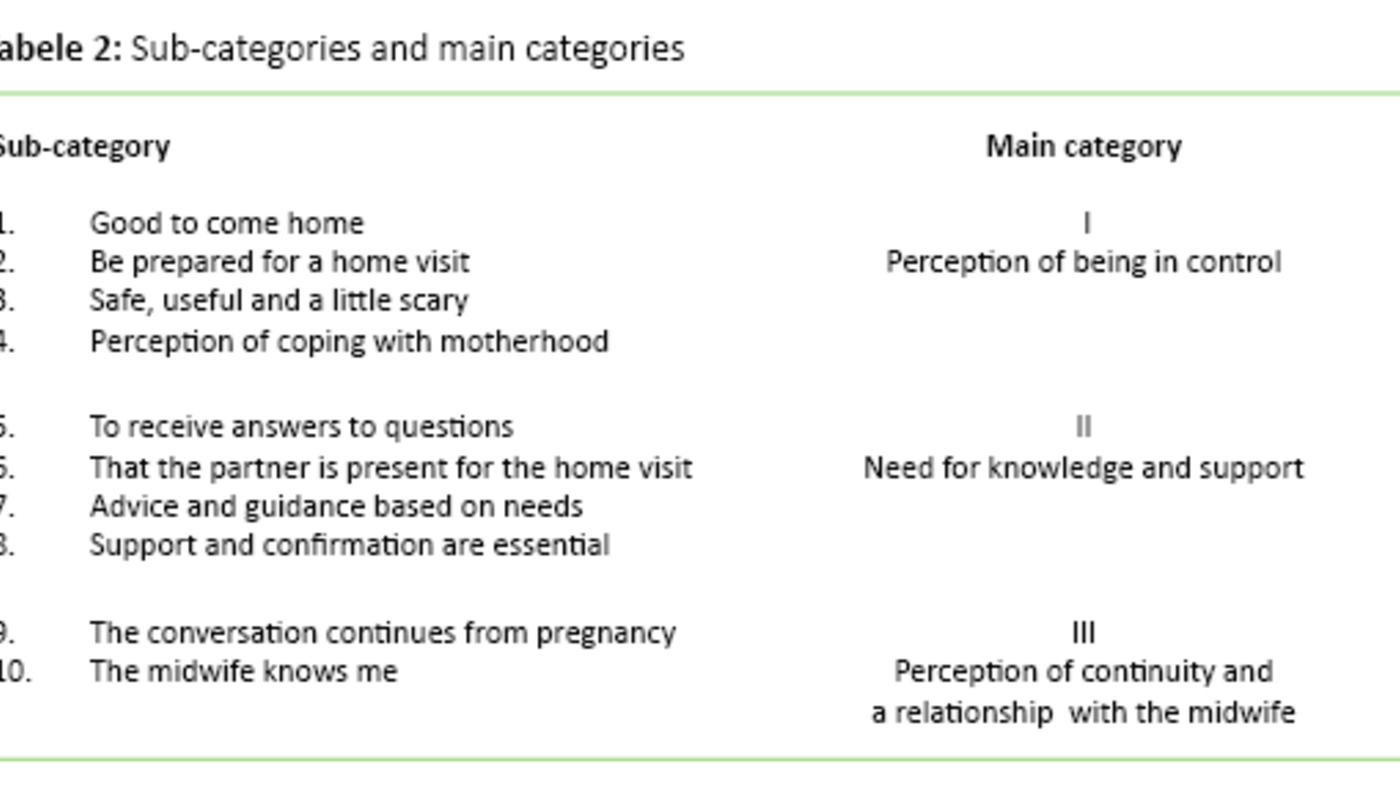

Table 2 shows the categories that emerged during the analysis.

The perception of being in control

The women felt that the home visit helped provide security and calm in a hectic postnatal period. Many of them told us that they looked forward to the midwife’s visit. The women were aware of what the midwife could provide, and that the visit was voluntary and agreed beforehand. The women thus felt that they were prepared for the visit and in control of the situation:

‘When you come home, it’s much calmer than being in the hospital, it’s easier to think through the things that you wonder about or questions to be asked.’

‘It was very good that we were prepared ... that way, the entire process becomes natural and informal.’

The women felt more secure when receiving support and confirmation from the midwife.

Prior to the home visit, many of the women had believed that the visit would entail checking or assessment of the home and of them as parents. One of the mothers described it as ‘scary’. All the women described the sense of security and the advantage of receiving help based on their own needs as the key element of the home visit:

‘The impression that I had beforehand, what I learned from others, was that they come to check that everything is in order in the house and all that, but certainly also because it was the midwife, it felt just like having a friend visiting, a friend who also has the knowledge.’

The women described various experiences of coping associated with matters being as expected, and that they were able to cope with new roles and tasks. One woman had a strong perception of coping in the context of the birth itself. She described it as important for her to share this experience with the midwife during the home visit:

‘So that was really great, because now I can finally do it, and had the confirmation that I can’ (breastfeeding).

‘We did everything ourselves ... I really felt that sense of coping.’

The need for knowledge and support

During the home visit, it is crucial that the women receive answers to their questions, advice and guidance. The participants described the conversation with the midwife about the pregnancy and birth as essential for their understanding and confirmation:

‘We had prepared ourselves ... made notes of questions and such, so that we could ask about what we were unsure of.’

‘Then we talked a lot about the birth ... I really needed that – that it was her I told what I felt about or what my hopes were before the birth ... because she had been involved all the way, even though she hadn’t been present during the birth itself.’

The partner’s role in the home visit was underscored as essential, because the partner could support the woman. The partner’s questions and experiences were considered:

‘It was good that he could be there too, then we receive the same information, and he also had some questions.’

Many reported that preparing adequately for the postnatal period was difficult, and that manoeuvring through the available information could present problems:

‘No matter how well one prepares, one can never prepare enough, because one cannot know what lies ahead.’

The women’s need for counselling and guidance varied from simple advice and confirmation of normality to more comprehensive guidance regarding matters such as breastfeeding, the birth or how to cope with overwhelming emotions. The women reported feeling safer in their new role after having been provided with support and confirmation by the midwife:

‘I feel quite a lot more trust in the midwife, it’s because I know that she’s a midwife, she knows about me too, not just the baby.’

‘It’s important to hear when one is so uncertain and emotional and very fearful of doing something wrong’ (about confirmation).

Perception of continuity and the relationship to the midwife

The home visit was described as meaningful and informal. The continuity in the relationship between the woman and the midwife emerged when the woman reported that the midwife was familiar with her condition during pregnancy and that the conversation ‘flowed’ immediately. Many described how they continued the conversation with the midwife during the consultations at the public health centre:

‘With the midwife it’s like: “Hello, how did the birth go?” and then we just start chatting.’

‘After all, the midwife knows how things have gone from day one, that makes it a different conversation.’

Many of the women reported that they felt confident in discussing their emotions and experiences. The relationship to the midwife was important and appeared to help reinforce the woman’s sense of coping. One of the women was previously unfamiliar with the midwife, but described how she felt the visit was useful because of the help and support that it provided to her:

‘It wouldn’t have been as easy to sit there and be open about emotions and the birth experience with someone who does not know you a little from before.’

‘When we were talking and I was telling her about it all, I could breathe, I felt relieved.’

Discussion

The women felt confident about their early discharge from the maternity ward when knowing that the midwife would come in a couple of days. Because information about the visit was provided beforehand, the woman could take control of the situation and choose whether or not to make use of this option. We interpret this to mean that predictability was important to the women. A Norwegian study confirms that being able to choose for oneself inspires confidence (17). Pursuant to the Patients’ and Users’ Rights Act, the woman is entitled to choose whether or not to accept a home visit (18).

The fact that the women believed that the visit involved being checked, can be seen as indicating that the women were in a vulnerable situation in their new role. The asymmetry of the situation, in which the woman was in need of the midwife’s help, may also have had an effect. Ruyter and collaborators claim that autonomy is not a constant, but varies in light of the condition and situation of the individual (19). The postpartum woman is in a vulnerable situation, and it may therefore be said that her autonomy may be limited. Establishing a good relationship may help the party involved in the relationship reinforce and regain her autonomy (20, 21). After the visit, none of the women felt that it had constituted a control measure. This might be associated with the fact that the relationship between the woman and the midwife was known, and that the midwife was skilled in building relationships.

All the women felt a need to discuss issues associated with the child’s weight and breastfeeding.

Other research shows that women who have received home visits are more satisfied than those who have been in a maternity ward. This is most likely due to the busy environment at the hospital and the perceived importance of continuity and relational interaction between the midwife and the woman (7, 8). When the woman feels accommodated and trusts the midwife and her skills, she can work to enhance her own insight and self-confidence through this relationship. Thereby, she obtains a better opportunity to make correct and autonomous decisions for herself and her child. This is crucial in the formation of a secure basis for the ties between mother and child, as well as for the child’s health in later life (20).

The need for knowledge and support

At the stage when breastfeeding had barely started, guidance in breastfeeding and feeding was essential. Breastfeeding is appropriate both in terms of child nutrition and bonding. Guidance on breastfeeding in the early postnatal period, combined with home visits, may help sustain breastfeeding over time (22, 23). All the women felt the need to discuss issues associated with the child’s weight and breastfeeding. Other important topics included how to understand the child’s signals, sleep balance and the woman’s own health.

This study shows that the ability to accommodate the child’s needs may help the women to feel a sense of coping. Other studies confirm that the child’s health and well-being are crucial for the mothers’ feeling of confidence (6, 24, 25). Seemingly, when the women felt confident about the condition of the child, they could start thinking of themselves and their own needs. Talking about the birth was important to the women. We interpret this to mean that a discussion of expectations and actual experiences could help enhance the understanding of the birth process. Most of the women described it as appropriate and natural to have this conversation with the midwife, whom they knew from before. However, one woman described it as rewarding despite her not having previous acquaintance with the midwife.

The women felt confident in talking to a midwife they knew from their pregnancy period.

Aune et al. found that during the home visit, attention was focused on perceptions and experiences from pregnancy and birth, more than on future events (9). These findings may confirm that the perception of coherence and understanding of the process are important to the women. This may corroborate the argument that midwifery skills are crucial in the early postnatal period. The women expressed difficulty in preparing adequately for the postnatal period, and felt secure when the midwife could contribute her knowledge and skills. Women may need support to take care of themselves during the first week of the postnatal period (26, 10).

The objective of the guidance is to support the woman and to provide her with better knowledge and skills to enhance her self-confidence and self-efficacy. She can thus better address her new life situation and have power, influence and control of the situation (27, 28). The study appears to show that attention to individual needs and the ability to cope helped promote empowerment in the woman, which is consistent with other studies (8, 9, 29).

Having their partner present during the home visit was important for the majority of the women. Giving both of them the opportunity to discuss their questions and thoughts may help bolster the chances of a positive and equal collaboration in their new family setting (30, 31). If the woman is provided with information to be shared later with her partner, this may result in an asymmetric relationship (19, 20).

Perception of continuity and the relationship with the midwife

The study shows that the women felt confident in speaking with a midwife they knew from their pregnancy period and who had competence with regard to the newborn child as well to them as women. The continuity in the relationship is claimed to help bolster the women’s trust in the midwife’s expertise, advice and guidance, and in addition, the midwife can reinforce the women’s trust in their own resources (9, 32).

Many of the women described how they were overwhelmed by the initial period. The postnatal period is a vulnerable time for the woman because of the major changes that occur in her life (20, 33, 34). The midwife’s skills in communication and relationship-building appear to have an impact on the benefits that the woman derives from the home visit. Razurel et al. emphasise that emotional and social support is more crucial than practical knowledge during the early postnatal period (35). Whether the women were facing challenges or a normal process appeared to have little bearing on the need to obtain support or confirmation from the midwife. The support and confirmation that the midwife gave regarding the women’s choices or understanding of the situation could provide them with confidence, self-efficacy and a sense of coping. These are the main elements of empowerment thinking and can thus be interpreted as evidence that the midwife may help promote empowerment in the woman (11, 28).

The midwife may use her skills and previous relationship with the mother to accommodate her individual needs (32, 36). This could be an opportunity for continuity, even if the woman and the midwife are not known to each other from the pregnancy period. The midwife’s professional skills may help the woman perceive consistency and continuity in her understanding of the process. Studies show that women are greatly satisfied with the information and guidance provided by the midwife during the home visit (7, 8).

Whether the women were facing challenges or a normal process appeared to have little bearing on the need to obtain support or confirmation from the midwife.

The tasks of the midwife and the health visitor overlap during the home visit; for example, both may provide guidance on breastfeeding. They both focus on health promotion and include the family, the woman and the newborn child, but they possess different skills. The midwife’s skills include maternal health, pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period (37). She makes a home visit one to six days after the woman’s discharge from hospital, when she mainly focuses on the woman and the newborn child. The midwife may, for example, help strengthen the woman in her new life situation, which may assist in developing her skills as a mother. The health visitor has competence with regard to children, adolescents and their families (38). She makes a home visit six days to two weeks after discharge, focusing on the child’s health and development within the family. The health visitor may, for example, help in establishing positive bonding and good family relationships.

Better collaboration and understanding between health visitors and midwives during home visits may help better adapt the follow-up options for the early postnatal period to the woman, the child and the individual needs of the family. Moreover, it is likely that better interdisciplinary collaboration and familiarity with each other’s competencies may help ensure a better utilisation of resources and competencies.

Validity of the study

The study elucidates the perceptions and experiences of women from home visits by a municipal midwife in the early postnatal period. This topic has not previously been highlighted in Norwegian studies. The first author is a midwife with experience from community midwifery services. She is familiar with the conditions related to the topic that the study seeks to explore. This knowledge may help lend considerable relevance to the questions in the interview guide, but may also entail the risk that certain elements are overlooked or underestimated. We attempted to reduce this risk by clarifying our preconceptions throughout the research process (12, 16, 39).

The fact that the first author is a midwife may have influenced the women, causing them not to report any negative aspects out of fear of appearing unfriendly. To reduce the risk of such an effect, the first author informed the participants about her role as a researcher prior to the interview. No questions related to midwifery were brought up during or after the interview. Reflections were noted immediately after the interview and used for purposes of validation during the analysis. We believe that undertaking the interviews in the woman’s home environment helps reinforce the validity and credibility of the study (40). The women were recruited by locally employed midwives on the basis of availability, which may have had an effect, in that the women’s attitude to home visits by a midwife was known in advance (15). Efforts were made to reduce this effect by recruiting the women consecutively after the home visits had been undertaken. This may help enhance the validity of the study.

Conclusion

The study shows that a community midwife may help establish a perception of consistency and continuity by maintaining regular contact with the woman throughout the pregnancy until the home visit. The visit may provide an opportunity to accommodate the women’s individual needs, in light of the previously established relationship and the midwife’s competence in maternal health, pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period. When the woman feels that she is regarded as ‘an expert on her own situation’, is permitted to participate in the process of identifying the best solutions and thus remain in control of her own life situation, this may help reinforce her empowerment.

Home visits by a midwife may thus help advance the woman’s perception of coping and reinforce her empowerment, which will promote the health of the woman, the child and the family. The midwife and the health visitor possess different skills, and home visits by both may be appropriate in terms of health promotion. Interdisciplinary collaboration is important, and more research on how best to make use of resources and skills is needed.

References

1. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal retningslinje for barselomsorgen. Nytt liv og trygg barseltid for familien. Oslo. 2014. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/nasjonal-faglig-retningslinje-for-barselomsorgen-nytt-liv-og-trygg-barseltid-for-familien. (Downloaded 18.06.2015).

2. Venheim MA. Barselomsorg : Plager og komplikasjoner. In: Tegnander E, Brunstad A. (ed). Jordmorboka: ansvar, funksjon og arbeidsområde. Oslo: Akribe; 2010.

3. Lundgren I, Berg M. Central concepts in the midwife-woman relationship. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences. 2007;21(2):220–8.

4. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Samhandlingsreformen: rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. Oslo: Regjeringen. 2009.

5. Den norske jordmorforening. Høringssvar. 2015. Availabe at: http://www.jordmorforeningen.no/Media/Filer/Hoeringssvar/Dnj_hoeringsvar_prioteringer_helsetjenesten_2015. (Downloaded 15.05.15).

6. Hildingsson IM, Sandin-Bojö A-K. «What is could indeed be better» – Swedish women’s perceptions of early postnatal care. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):737–44.

7. Fenwick J, Butt J, Dhaliwal S, Hauck Y, Schmied V. Western Australian women's perceptions of the style and quality of midwifery postnatal care in hospital and at home. Women and Birth. 2010;23(1):10–21.

8. Johansson K, Aarts C, Darj E. First-time parents' experiences of home-based postnatal care in Sweden. Uppsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010;115(2):131–7.

9. Aune I, Dahlberg MU, Ingebrigtsen O. Parents’ experiences of midwifery students providing continuity of care. Midwifery. 2012;28(4):432–8.

10. Hjälmhult E, Lomborg K. Managing the first period at home with a newborn: a grounded theory study of mothers’ experiences. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences. 2012;26(4):654–62.

11. Tveiten S. Empowerment og veiledning : sykepleierens pedagogiske funksjon i helsefremmende arbeid. I: Gammersvik Å, Larsen T. (red). Helsefremmende sykepleie – i teori og praksis. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad & Bjørke. 2012.

12. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 2. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2009.

13. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9. ed. Wolters Kluwer Health Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012.

14. De nasjonale forskningsetiske komiteer. Forskningsetiske retningslinjer for samfunnsvitenskap, humaniora, juss og teologi. 2006. Available at: https://www.etikkom.no/forskningsetiske-retningslinjer/Samfunnsvitenskap-jus-og-humaniora/. (Downloaded 18.06.2015).

15. Thagaard T. Systematikk og innlevelse. En innføring i kvalitativ metode. 4. ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad & Bjørke. 2013.

16. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. En innføring. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. 2013.

17. Henriksen L. Hva betyr helhet og kontinuitet i svangerskap, fødsel og barselomsorg for kvinner? En evaluering av Barsel hjemme, et prosjekt fra Oslo. 2010.

18. Lovdata. Lov om pasient- og brukerrettigheter. 2. juli 1999; nr. 63. [Pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven].

19. Ruyter KW, Førde R, Solbakk JH. Medisinsk og helsefaglig etikk. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2014.

20. Schibbye A-LL. Relasjoner: et dialektisk perspektiv på eksistensiell og psykodynamisk psykoterapi. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. 2012.

21. Goering S. Postnatal reproductive autonomy: promoting relational autonomy and self-trust in new parents. Bioethics. 2009;23(1):9–19.

22. Hansen MN. Barseltiden og amming. In: Tegnander E, Brunstad A. (ed). Jordmorboka: ansvar, funksjon og arbeidsområde. Oslo: Akribe. 2010.

23. Kronborg H, Vaeth M, Kristensen I. The effect of early postpartum home visits by health visitors: a natural experiment. Public health nursing (Boston, Mass). 2012;29(4):289–301.

24. Forster DA, McLachlan HL, Rayner J, Yelland J, Gold L, Rayner S. The early postnatal period: exploring women's views, expectations and experiences of care using focus groups in Victoria, Australia. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 2008;8:27.

25. Persson EK, Fridlund B, Kvist LJ, Dykes A-K. Mothers’ sense of security in the first postnatal week: interview study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(1):105–16.

26. Fahey JO, Shenassa E. Understanding and meeting the needs of women in the postpartum period: The perinatal maternal health promotion model. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 2013;58(6):613–21.

27. Tveiten S. Veiledning: mer enn ord. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. 2013.

28. Askheim OP. Empowerment i helse- og sosialfaglig arbeid: floskel, styringsverktøy, eller frigjøringsstrategi? Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2012.

29. Askelsdottir B, Lam-de Jonge W, Edman G, Wiklund I. Home care after early discharge: impact on healthy mothers and newborns. Midwifery. 2013;29(8):927–34.

30. Rudman A, Waldenstrom U. Critical views on postpartum care expressed by new mothers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:178.

31. Ellberg L, Högberg U, Lindh V. «We feel like one, they see us as two»: new parents’ discontent with postnatal care. Midwifery. 2010;26(4):463–8.

32. Hunter B, Berg M, Lundgren I, Ólafsdóttir ÓÁ, Kirkham M. Relationships: The hidden threads in the tapestry of maternity care. Midwifery. 2008;24(2):132–7.

33. Brodén M. Graviditetens muligheder: en tid hvor relationer skabes og udvikles. København: Akademisk Forlag. 2004.

34. Reinar L,M. Barselomsorg; Plager og komplikasjoner. In: Tegnander E, Brunstad A. Jordmorboka: ansvar, funksjon og arbeidsområde. Oslo: Akribe. 2010.

35. Razurel C, Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Dupanloup A, Irion O, Epiney M. Stressful events, social support and coping strategies of primiparous women during the postpartum period: a qualitative study. Midwifery. 2011;27(2):237–42.

36. Aune I, Dahlberg U, Ingebrigtsen Or. Relational continuity as a model of care in practical midwifery studies. British Journal of Midwifery. 2011;19(8):515–23.

37. Rammeplan for jordmorutdanningen. Oslo: Regjeringen. 2005. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/kd/pla/2006/0002/ddd/pdfv/269373-rammeplan_for_jordmorutdanning_05.pdf. (Downloaded 18.06.2015).

38. Rammeplan for helsesøsterutdanningen. Oslo: Regjeringen. 2005. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/kd/pla/2006/0002/ddd/pdfv/269386-rammeplan_for_helsesosterutdanning_05.pdf. (Downloaded 18.06.2015).

39. Fog J. Med samtalen som udgangspunkt: det kvalitative forskningsinterview. København: Akademisk Forlag. 2004.

40. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24(2):105–12.

Comments