Are group-based self-management programmes suitable for all patients with type 2 diabetes?

Type 2 diabetes is an increasingly prevalent illness (1), and is placing significant demands on patient self-management. In Norway, as in the rest of Europe, the health authorities are investing in group-based self-management programmes to enhance coping skills and improve therapeutic compliance (2). Since 1997, approximately 60 Learning and Mastery Centres have been established in the specialist health services, and these arrange ‘Beginners’ courses’ for patients with type 2 diabetes (3). Since the introduction of the Coordination Reform in 2012, various generic self-management programmes have also been established by local authorities to support recommended health behaviour. In addition, the Norwegian Diabetes Association runs local motivation groups.

Socioeconomic factors

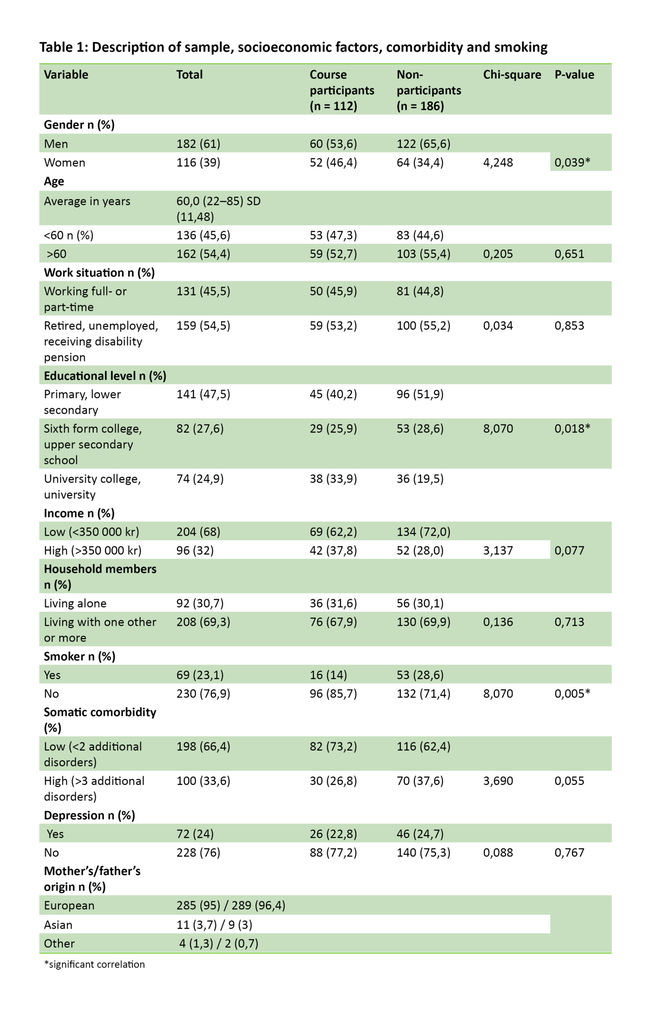

A summary from the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services shows that group-based self-management programmes have a positive effect on mental health, coping, relationships and knowledge of one’s disease (4). Long-term studies also indicate improved blood sugar control in persons with type 2 diabetes after group-based programmes (4-6). However, it is uncertain whether group-based self-management programmes are equally attractive for all groups of patients. Studies from other countries show selection bias, and differences are related to socioeconomic factors. Participation in group-based self-management programmes declines with lower economic status and increasing age (7).

A Canadian cross-sectional study of 46 553 patients with diabetes shows significant differences between participants and non-participants in group-based self-management programmes. Among non-participants, there is a preponderance of persons with a low educational level, advanced age, immigrant background, mental illness and comorbidity (8). One study also shows that patients recruited to the group programmes are those who initially exhibit the best health behaviour (9), which indicates that it is difficult to recruit persons who struggle to maintain appropriate health behaviour. Studies also indicate higher participation in group-based self-management programmes by women than by men (10, 11).

Selection bias

The association between patients’ socioeconomic status, gender, health behaviour and participation in group-based self-management programmes has not been investigated in Norway, but less use of health services in groups with a low socioeconomic status can generally be observed (12, 13). There are significant correlations between socioeconomic conditions and health (14-16), with a higher prevalence of obesity (17, 18) and smoking (19, 20), as well as little physical activity and low intake of fruit and vegetables (20, 21) in groups with a low socioeconomic status. With regard to type 2 diabetes, an increased prevalence can be observed in certain immigrant groups (22), in groups with a low educational level (23, 24) and among pensioners in receipt of disability benefit and persons who are not economically active (25).

According to Report No. 20 to the Storting, ‘National strategy to reduce social inequalities in health’ (15), the health services shall contribute to reducing social inequality, and Learning and Mastery Centres are described as an important arena for this (p. 54). Experience from other countries showing that group-based self-management programmes do not attract men or persons with a lower level of education to the same extent as other groups suggests a need to investigate how the current service functions in Norway. The purpose of this study was to investigate a sample of Norwegian patients with type 2 diabetes. We wanted to discover how large a proportion of these had participated in group-based self-management programmes and what characterises participants and non-participants. Are there differences in socioeconomic factors, gender and health behaviour?

Method

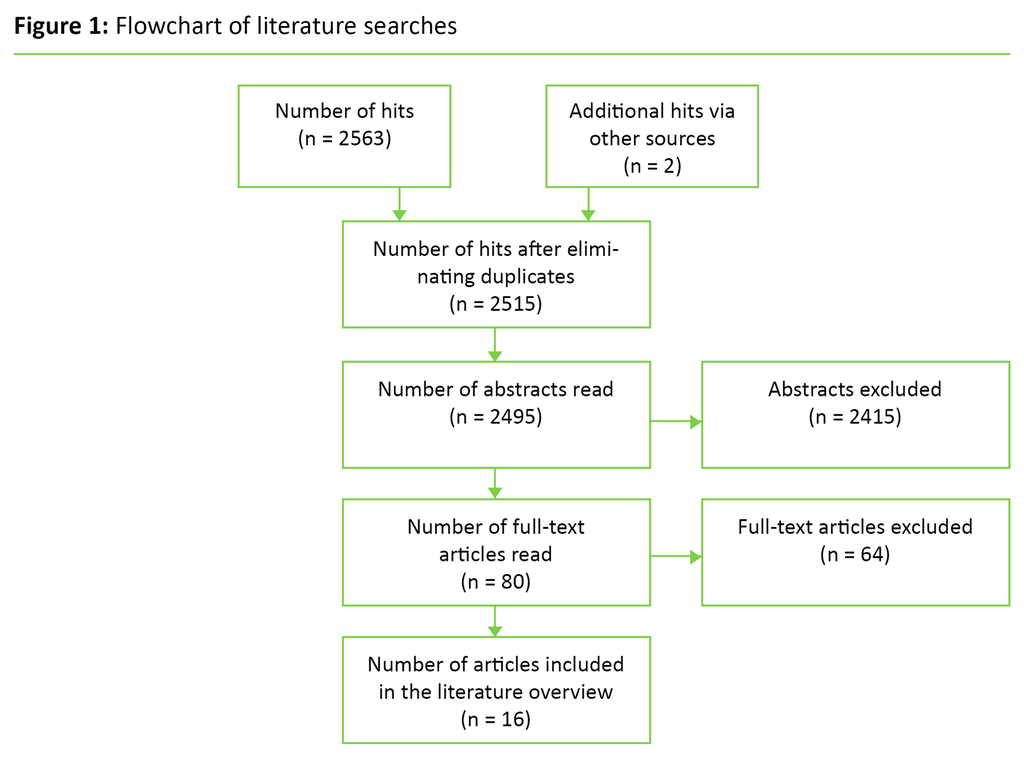

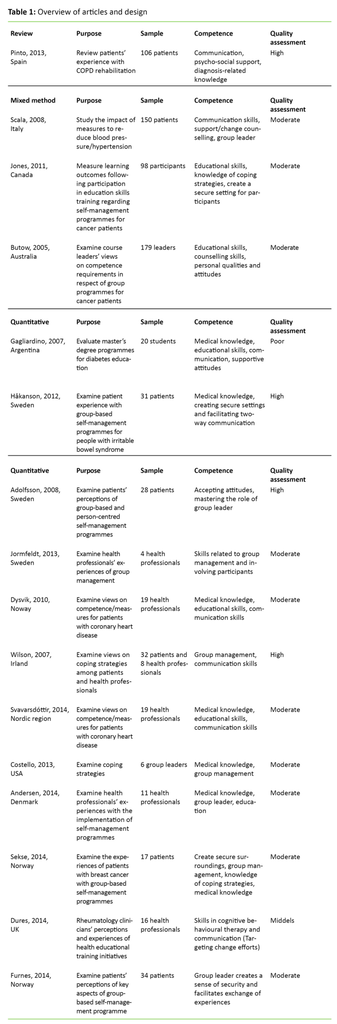

Our study is based on Norwegian data from an EU study (EU-WISE) that involves six European countries and is funded under the 7th Framework Programme. The study focuses on social networks and self-management of type 2 diabetes in economically deprived groups (26). Although EU-WISE has the express objective of reaching those who struggle with diabetes, there was no capacity to focus on the particular challenges of immigrant groups. In conformity with the protocol of EU-WISE, each participant country recruited 300 patients with type 2 diabetes in urban and rural areas to a descriptive cross-sectional study (26). Criteria for inclusion were that the patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, was older than 18 years and spoke Norwegian sufficiently well to be able to understand and complete a questionnaire.

We excluded patients with double diabetes, gestational diabetes, severe cognitive impairment, severe psychiatric illness, terminal illness and patients who had recently undergone extensive surgical or medical treatment. We approached outpatient clinics in the specialist health service with the aim of reaching patients who had been referred there by their GP, as such patients very often struggle to cope with the disease and develop long-term complications. Via a total of eight outpatient clinics in health trusts in Eastern Norway, diabetes nurses invited patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria to participate in the study in the period from August 2013 to February 2014. The study has been approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC). Participation was voluntary and the participants signed an informed consent form.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire that was used in EU-WISE was composed of various validated instruments (26). The study participants provided sociodemographic data (gender, age, highest completed education, employment status, number of household members, income level and parents’ country of birth). They were also asked whether they had participated in a group-based self-management programme. Comorbidity was measured using self-reporting, and the participants were asked whether they had been diagnosed with

- hypertension,

- high cholesterol,

- angina,

- heart attack,

- heart failure,

- TIA/ transient ischaemic attack,

- stroke,

- atherosclerosis/intermittent claudication, or

- depression.

They were also asked if they had undergone heart surgery.

The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) scale was used to measure health behaviour (27). The SDSCA scale asks respondents to indicate the number of days in the previous week that they have followed the recommended diet, been physically active, measured their blood sugar and checked their feet. Smoking is indicated in the yes/no category. SDSCA is internationally validated. In connection with the study, we have followed international principles for translation and adaptation to Norwegian conditions (28), but otherwise the instrument has not been validated in Norwegian.

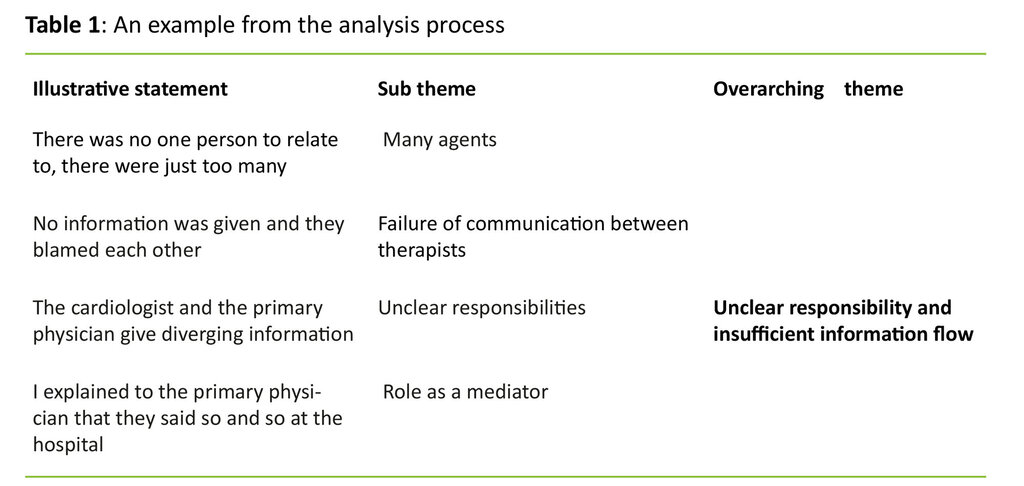

Analysis and coding

The dependent variable in the study is participation in group-based self-management programmes. We used sociodemographic data to describe the sample, and compared socioeconomic conditions, comorbidity and smoking in participants and non-participants in group-based self-management programmes. Somatic comorbidity was summarised (varying from zero to nine additional disorders) and categorised as ‘low comorbidity’ (zero to two disorders) or ‘high comorbidity’ (three or more disorders). Depression was analysed as a separate category as a mental health indicator.

In relation to health behaviour in the previous seven days, we divided the continuous data into three strata: those who did not self-monitor their illness (zero days per week), constituted the reference group. Those who self-monitored to some extent, i.e. one to four days per week, constituted one stratum, while those who self-monitored regularly, i.e. five to seven days per week, represented another stratum. In addition, gender was cross-tabulated with socioeconomic variables to obtain an overview of variation and comparability between men and women in the sample. We investigated statistical disparities using the chi-square test and logistic regression analysis. P-value for significance was set at < 0.05. We performed the analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.

Main result

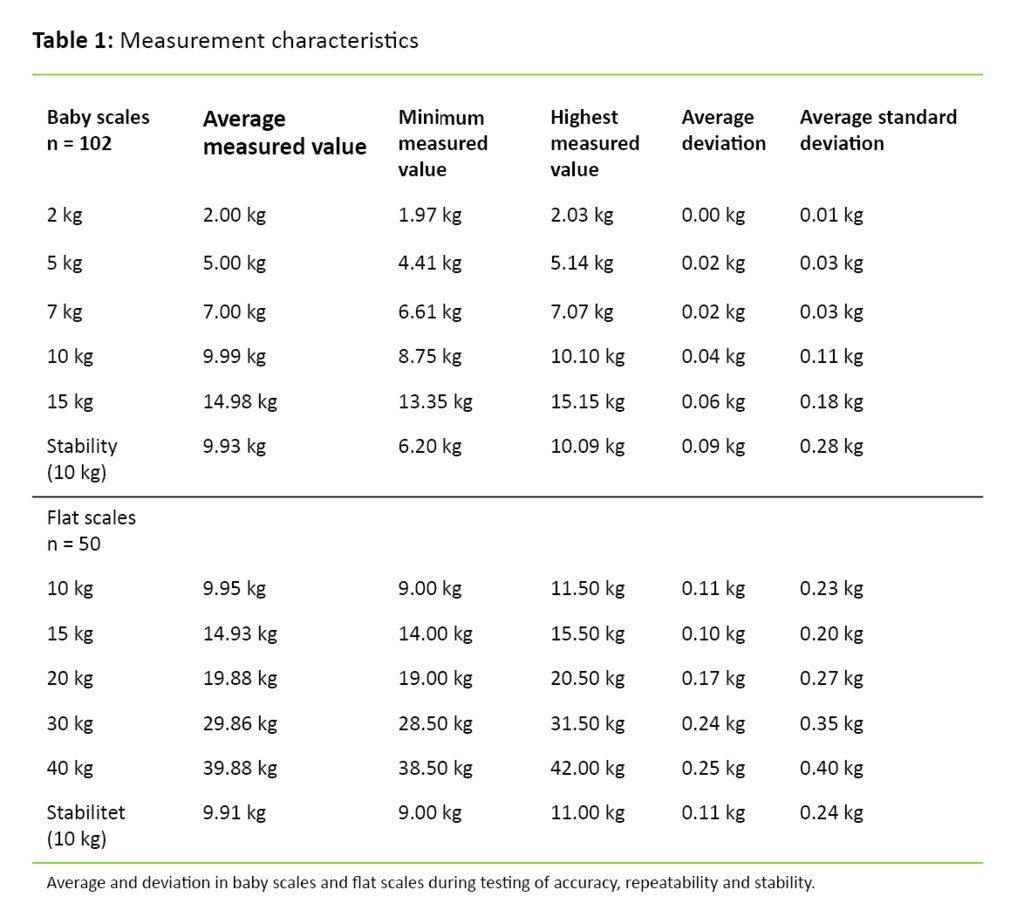

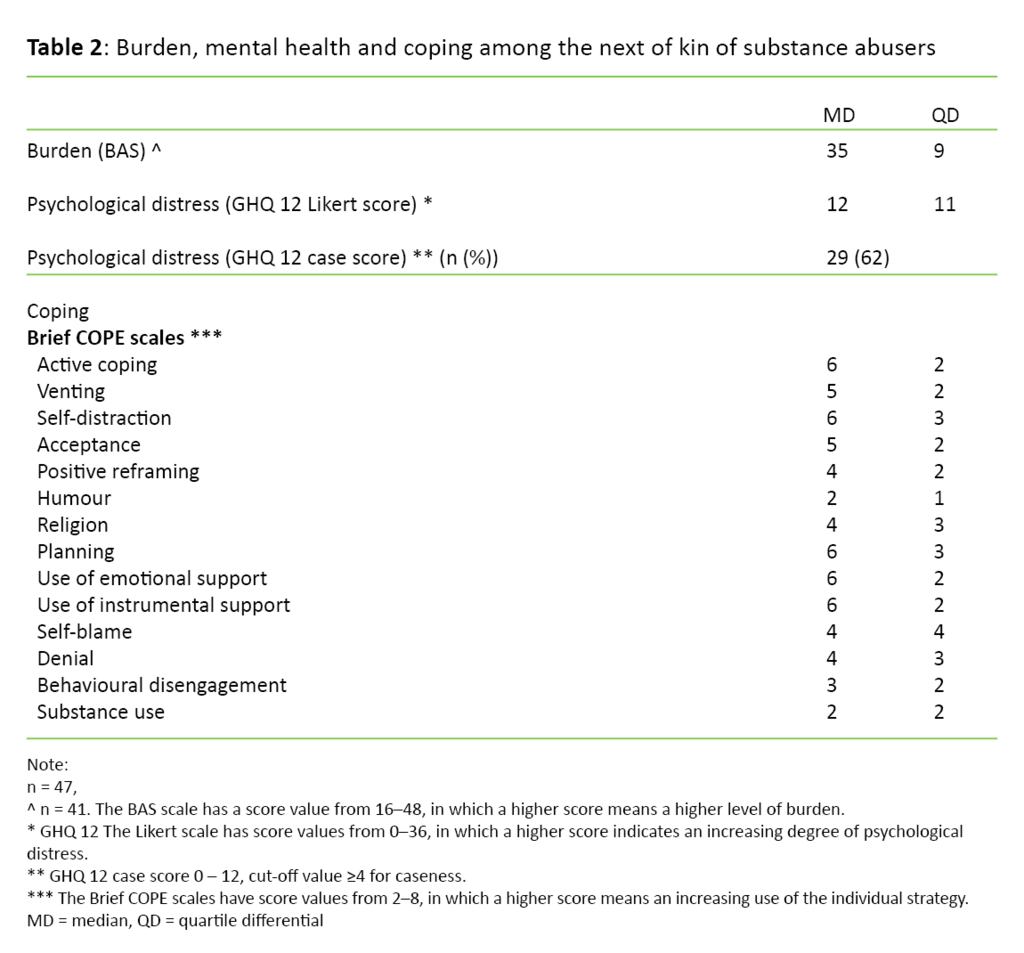

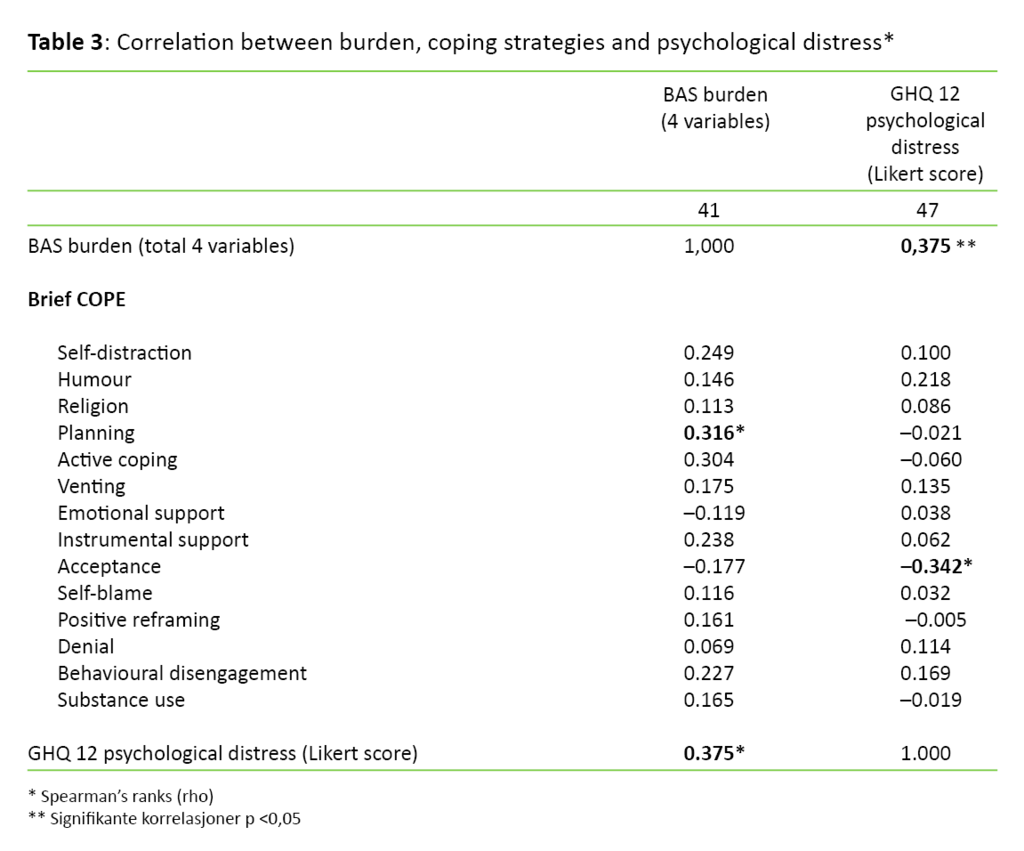

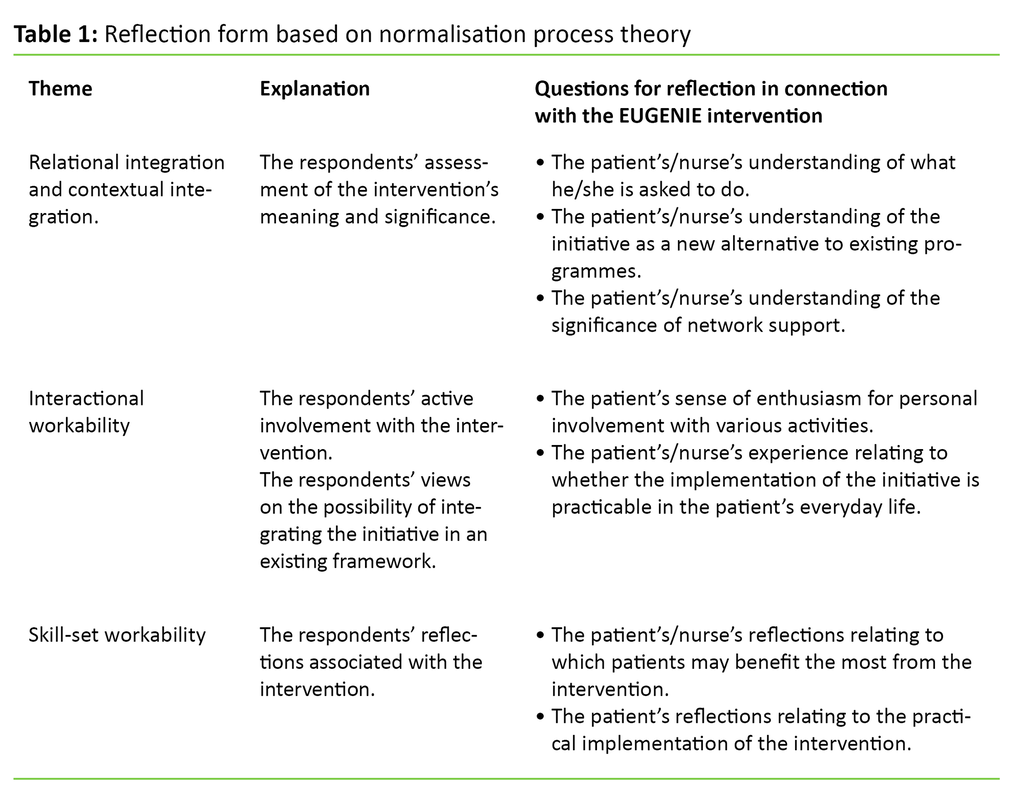

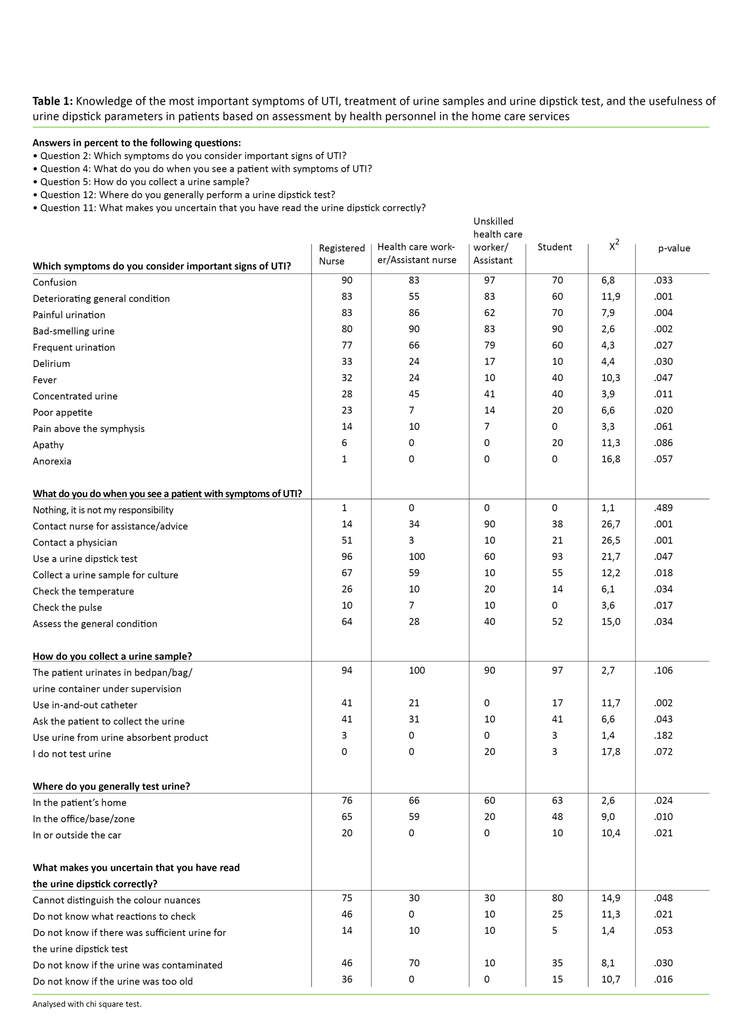

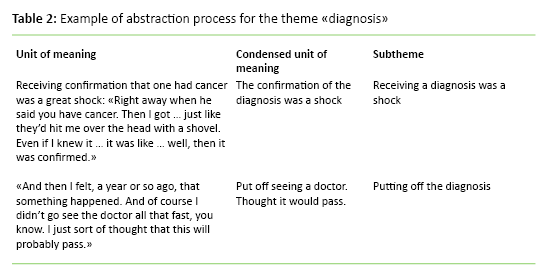

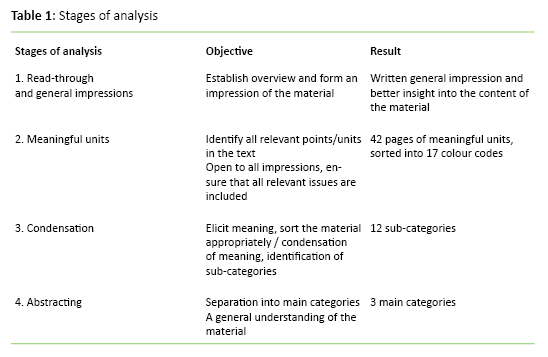

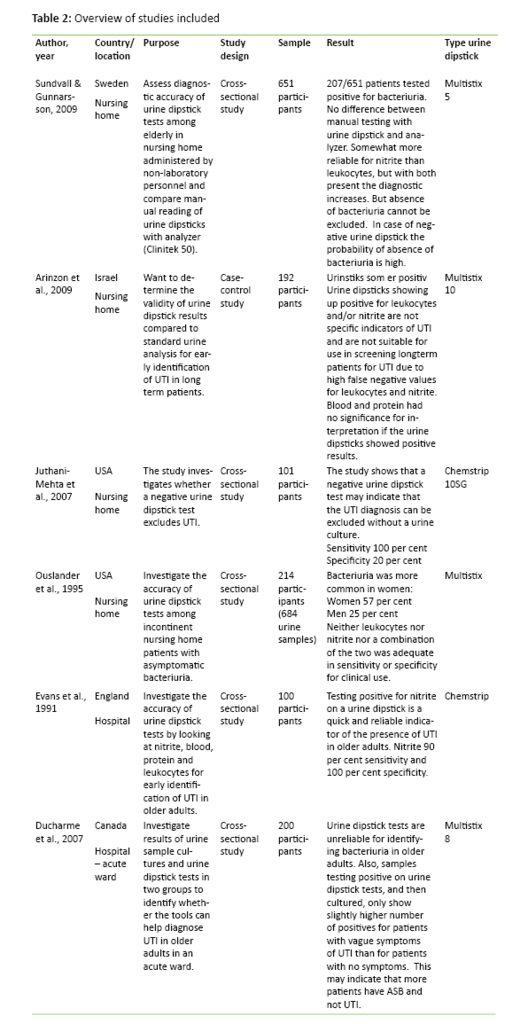

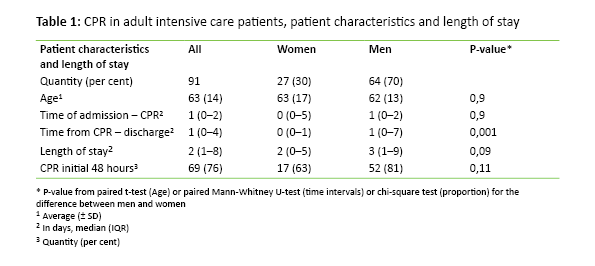

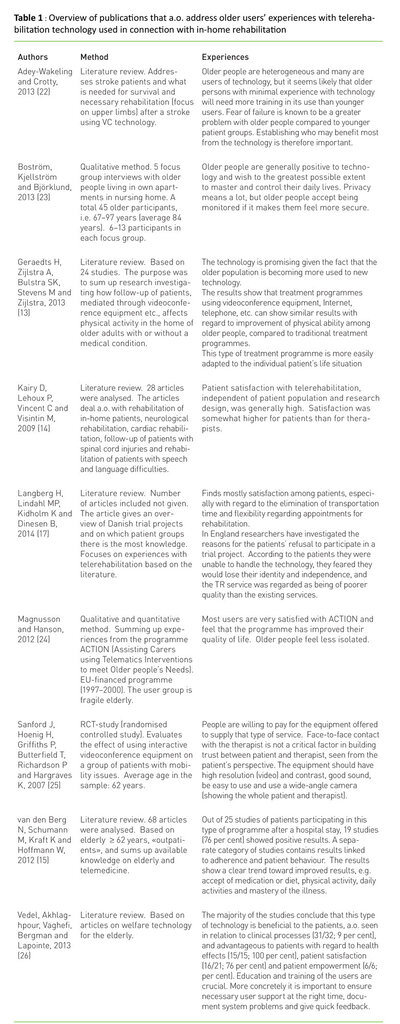

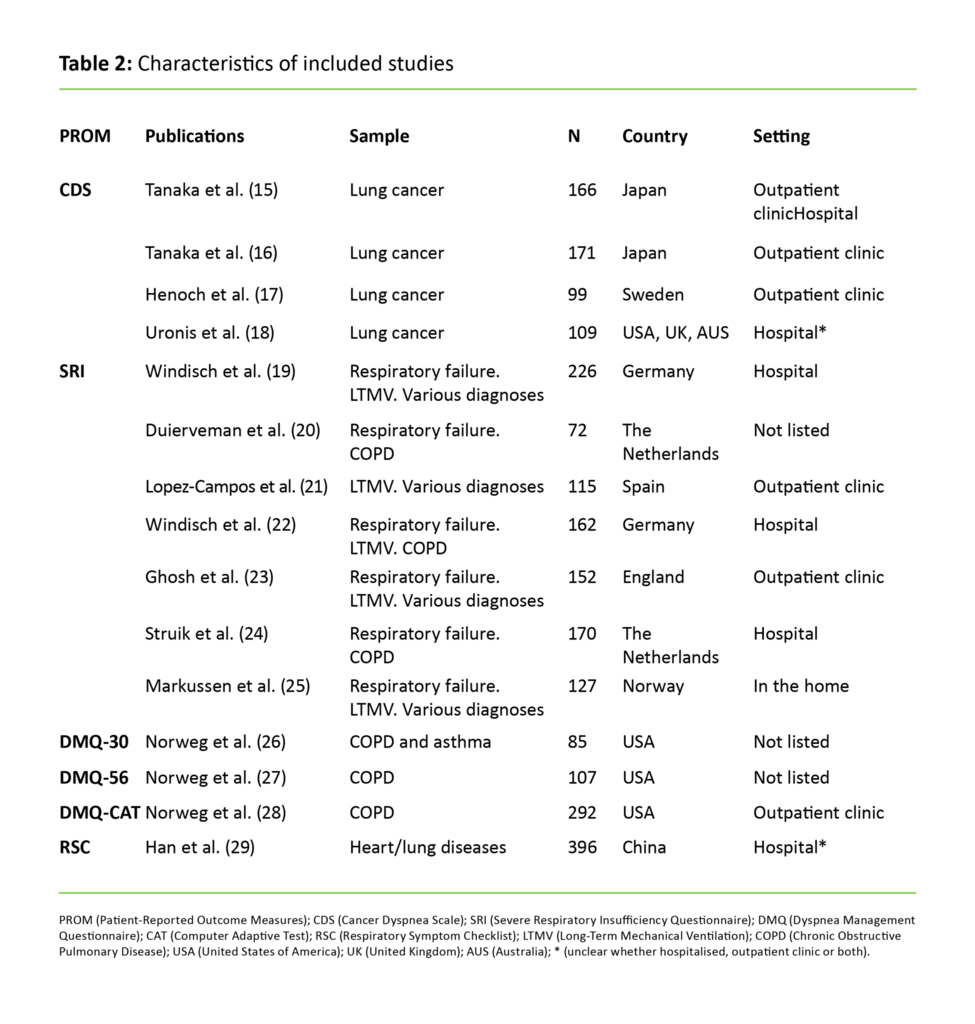

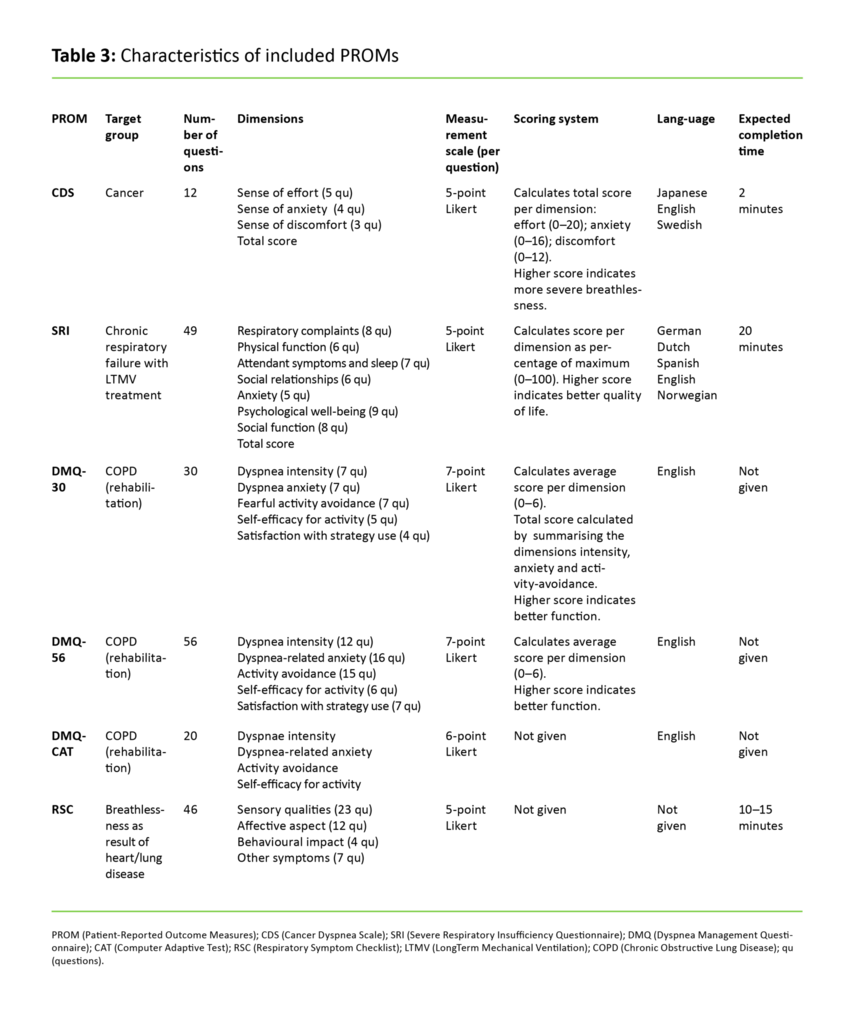

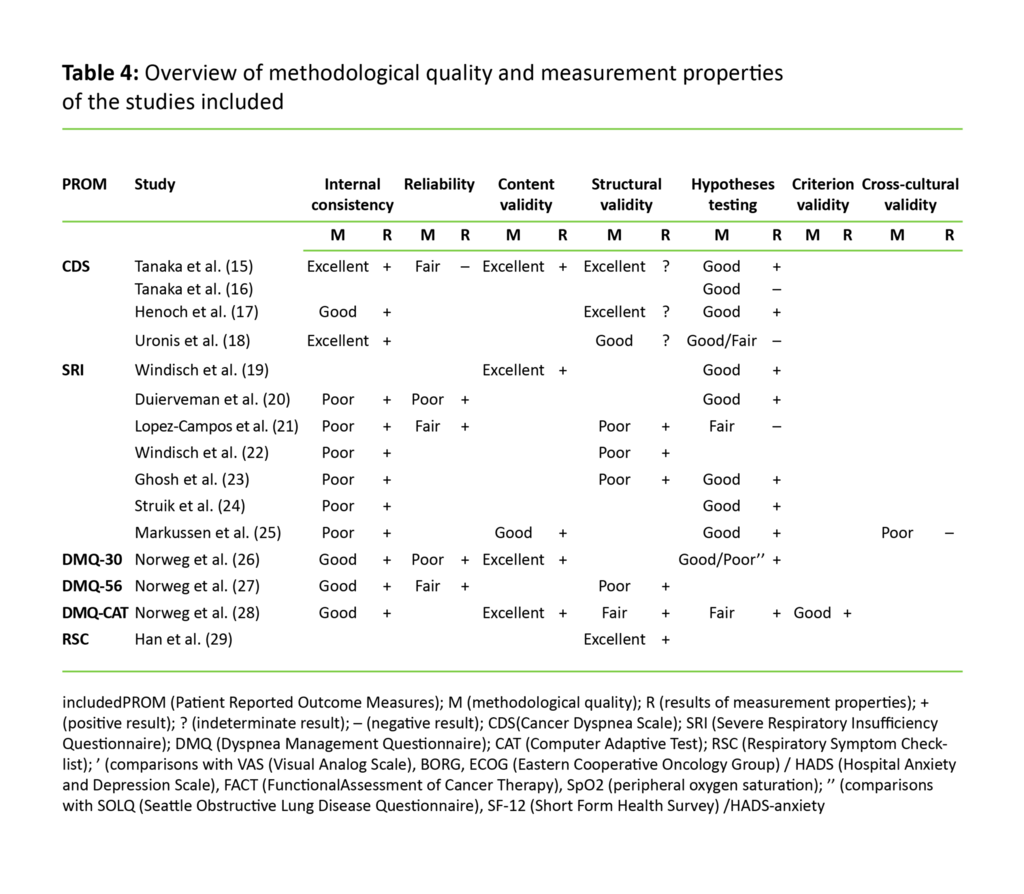

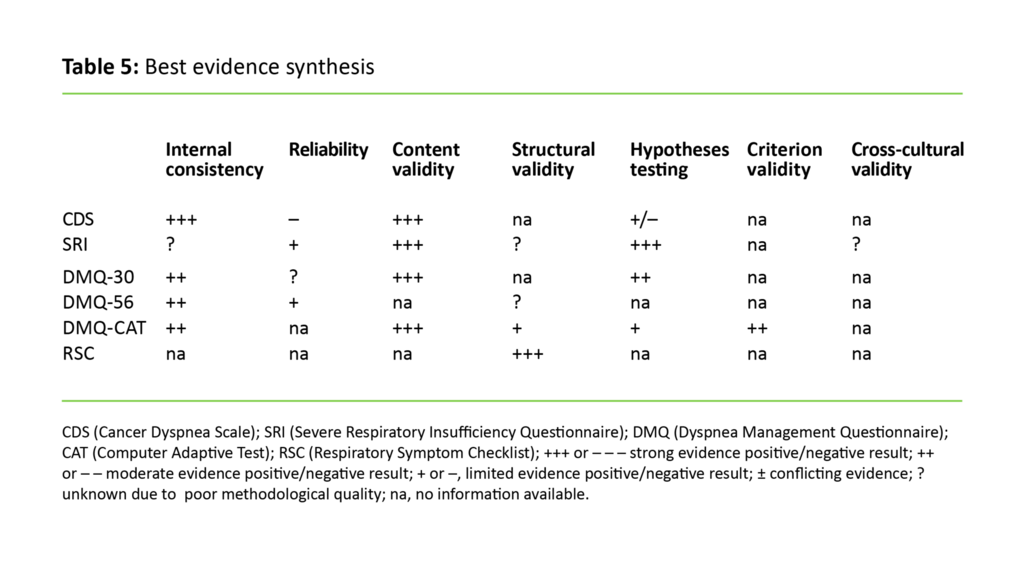

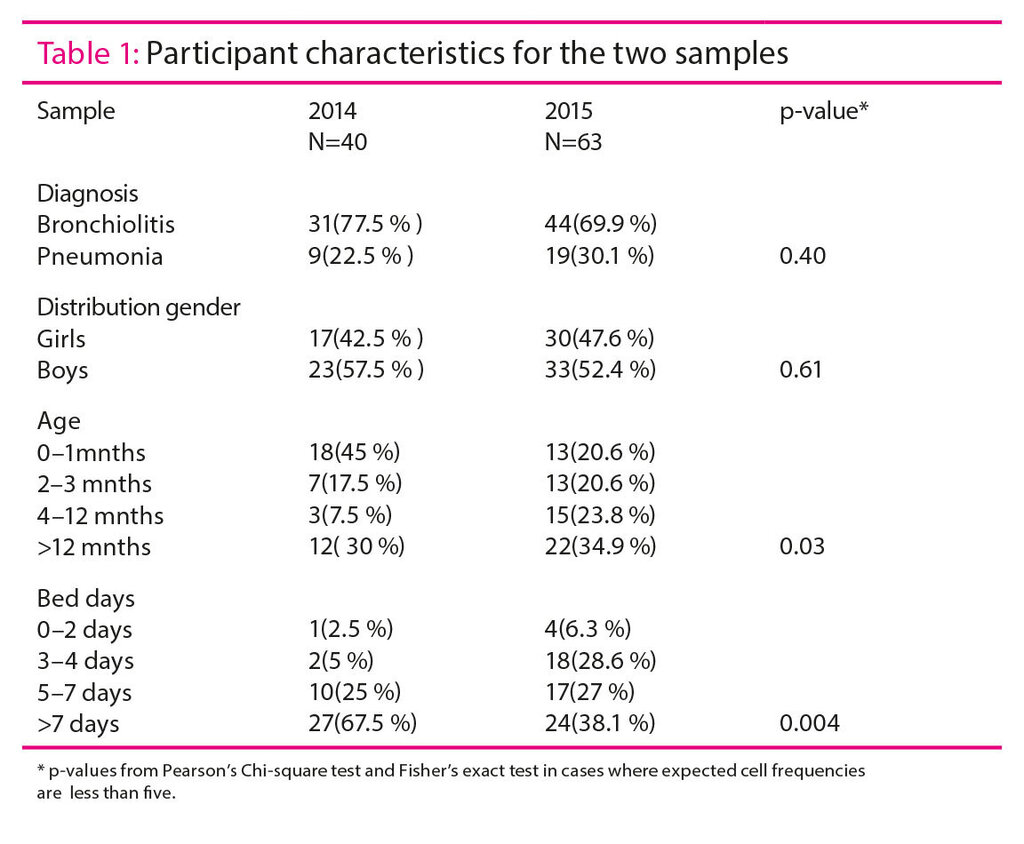

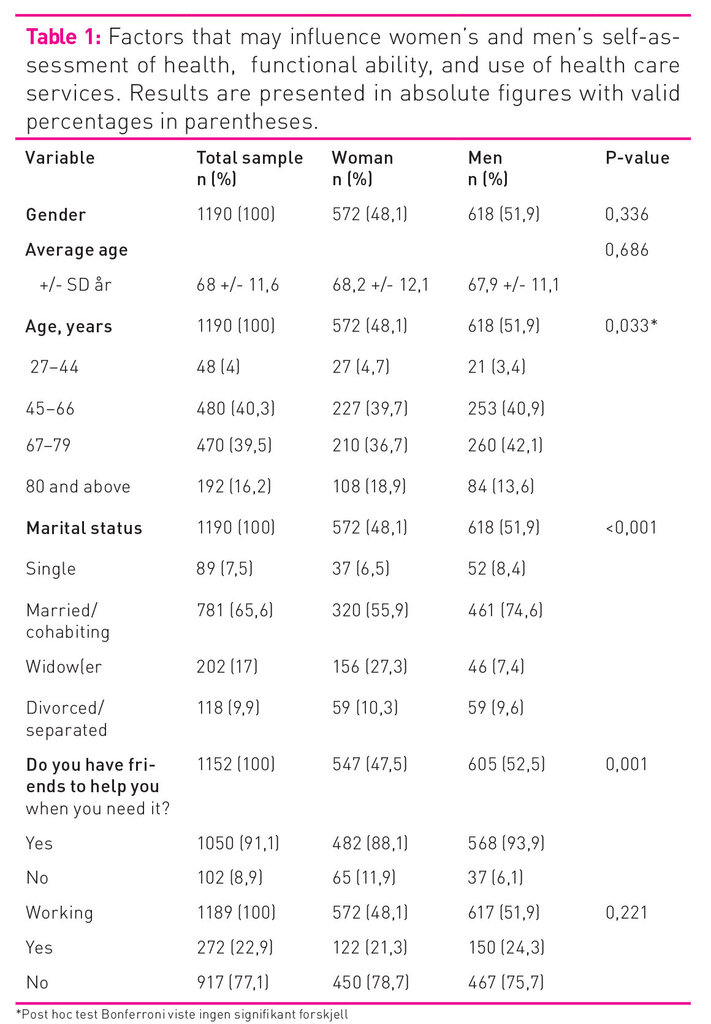

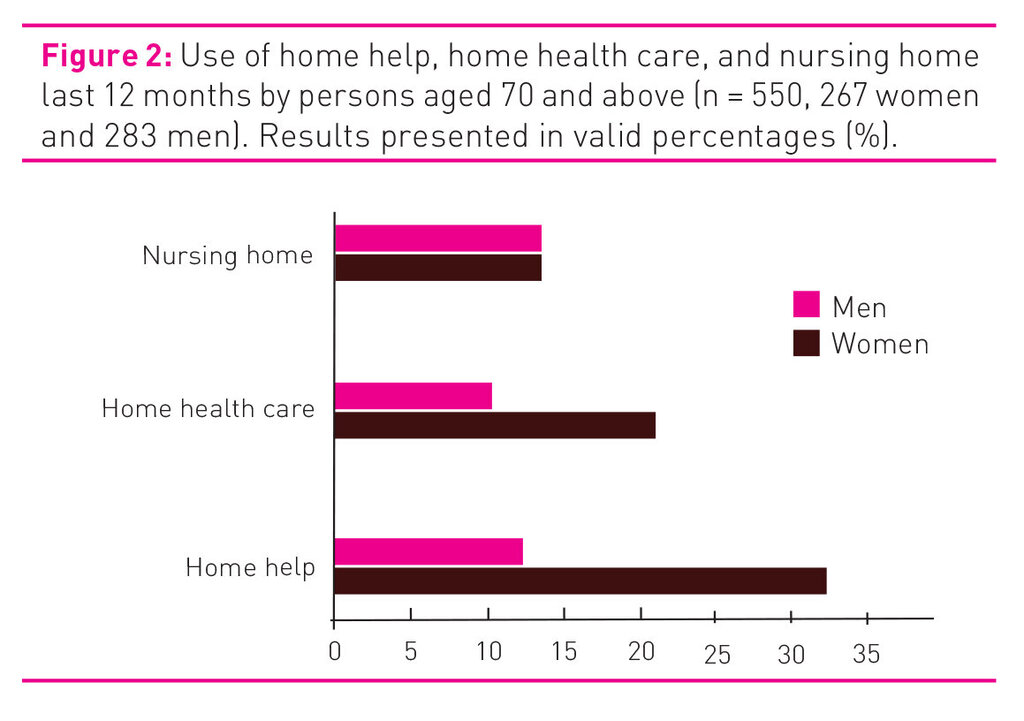

We asked 362 patients to take part in the study, and 298 gave their consent (response rate 82.4 per cent). The sample is presented in Table 1. The table shows that the average age of the sample was 60 years, with a slight preponderance of men. Somewhat less than half are in full-time or part-time work, while one-quarter are unemployed, disability pensioners or on sick leave. Almost half are only educated to primary/lower secondary level, and two-thirds have an annual income corresponding to, or less than, NOK 350 000. The vast majority have parents born in Norway or another European country.

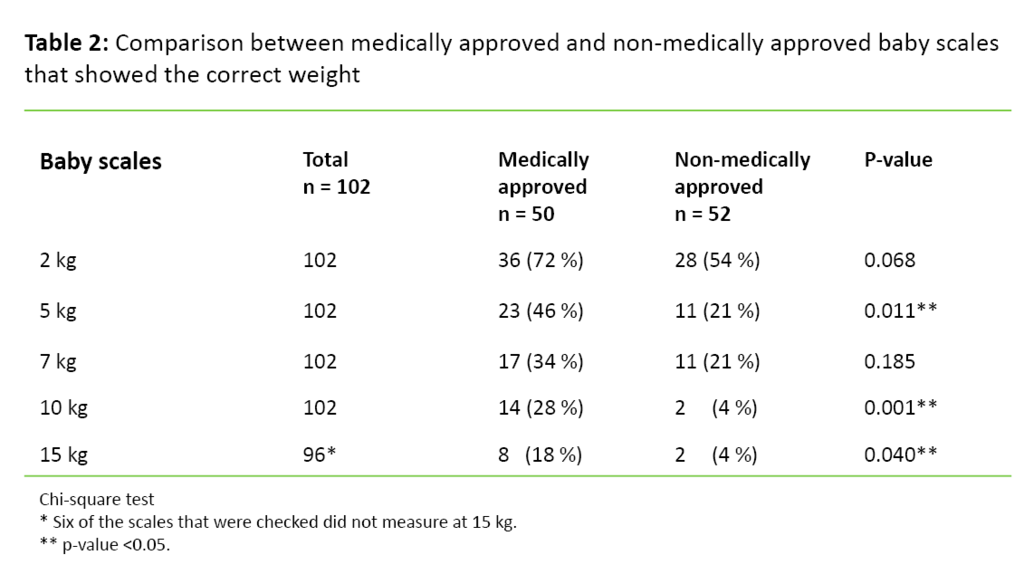

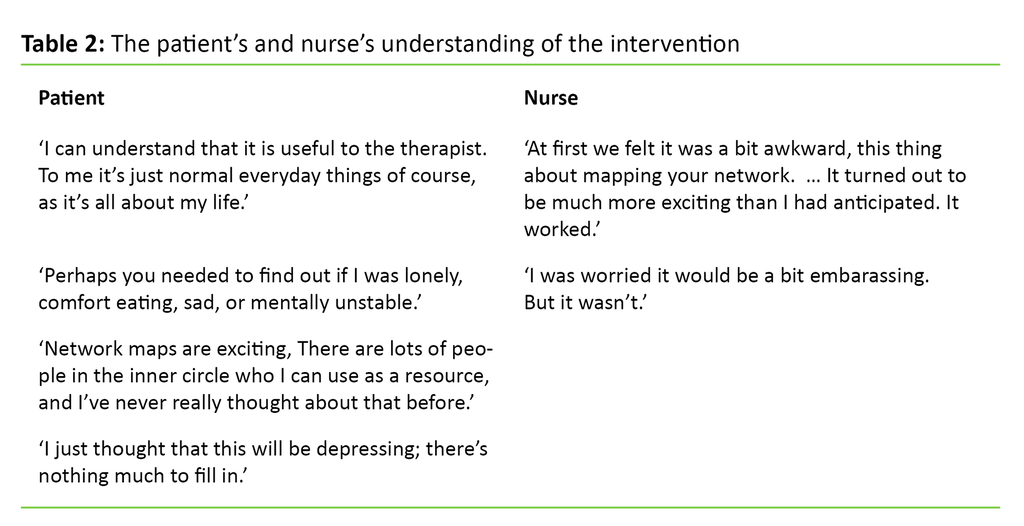

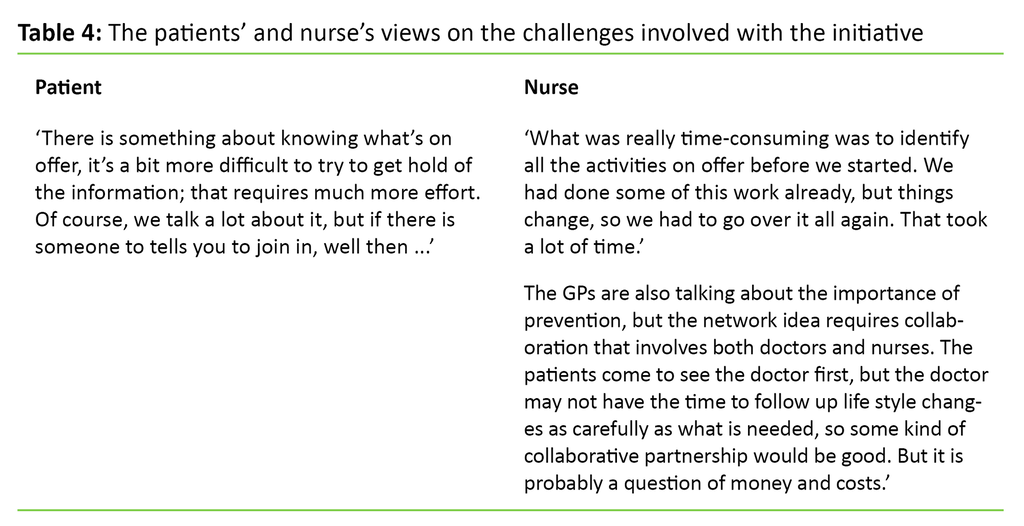

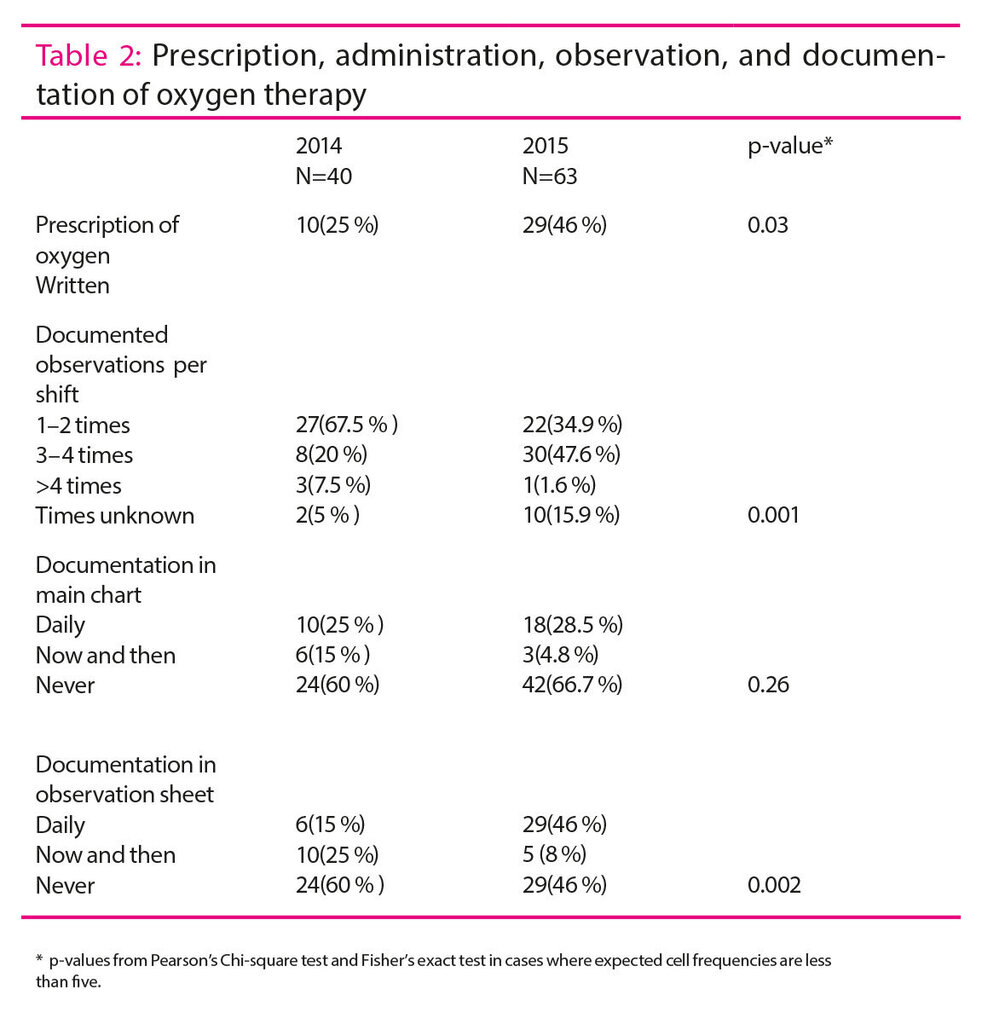

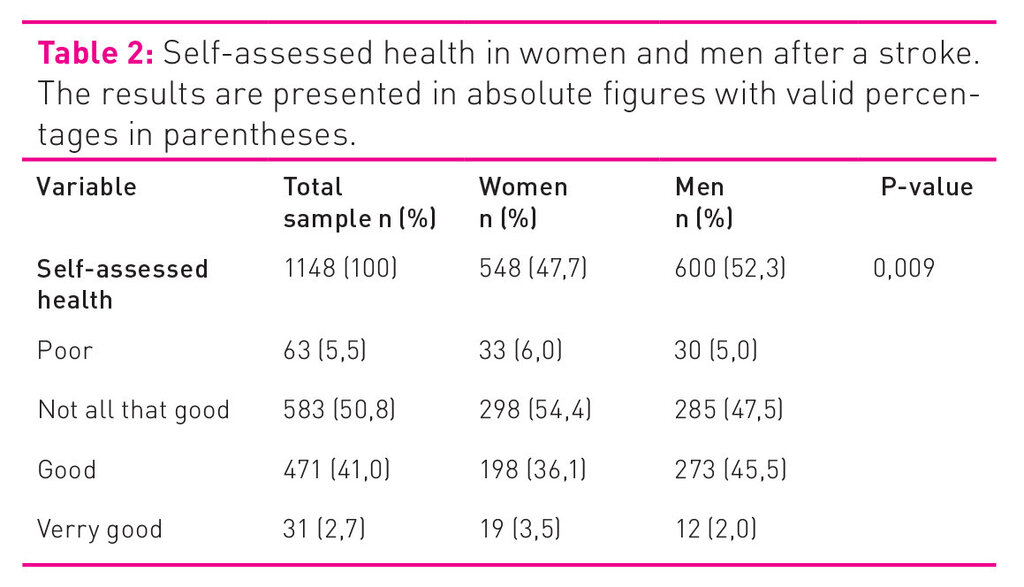

To the question of participation in group-based self-management programmes, 112 (38 per cent) respond that they have participated, while the remainder have not. With regard to socioeconomic conditions, there are significant differences between participants and non-participants in group-based self-management programmes in terms of gender, educational level and smoking (p <0.05). The proportion of women and those with a higher education is higher, and that of smokers is lower. There is an indication of covariance between low participation in group-based self-management programmes and patients with high comorbidity, but this is uncertain as the difference is not significant (p = 0.055).

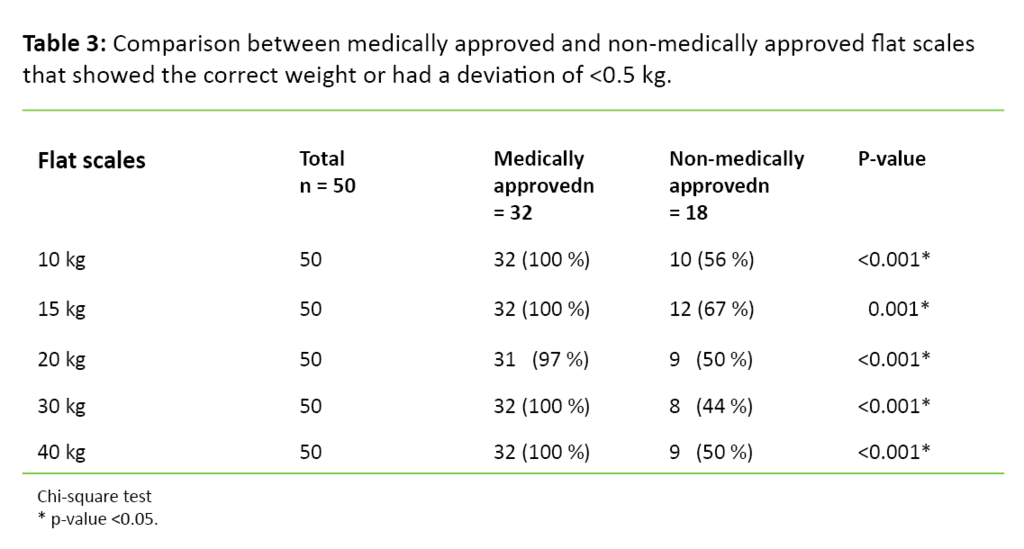

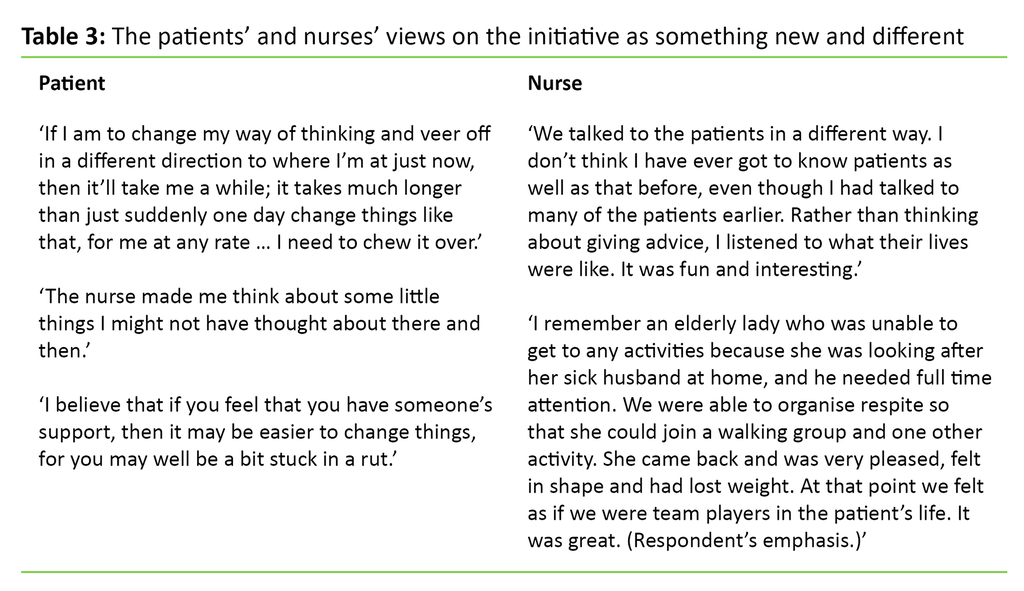

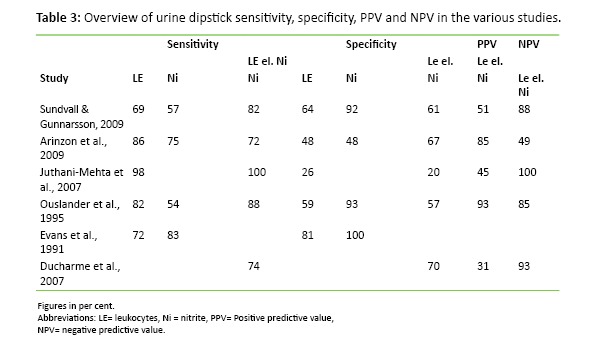

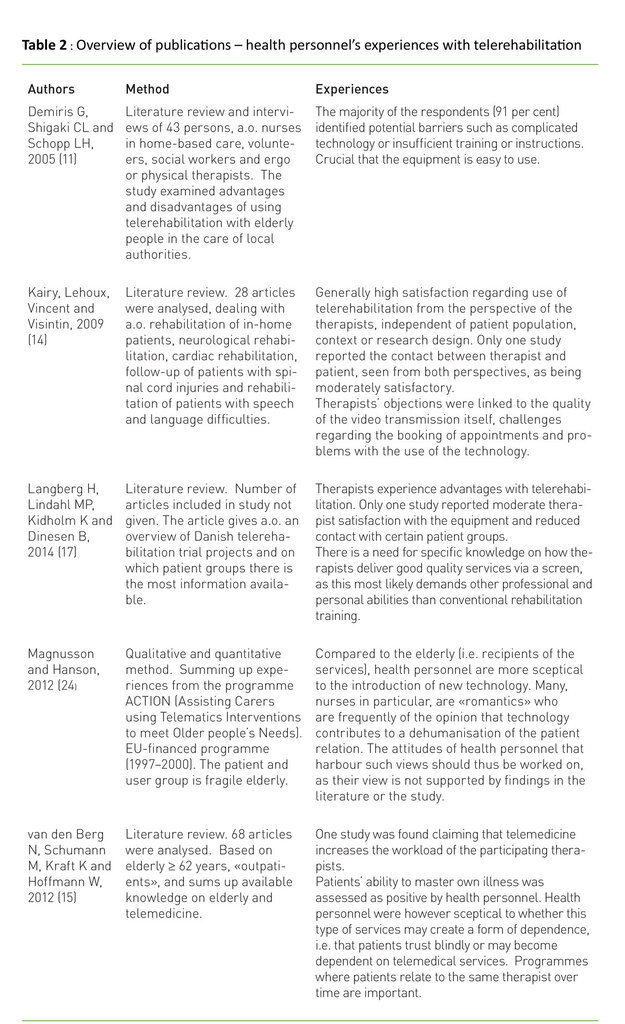

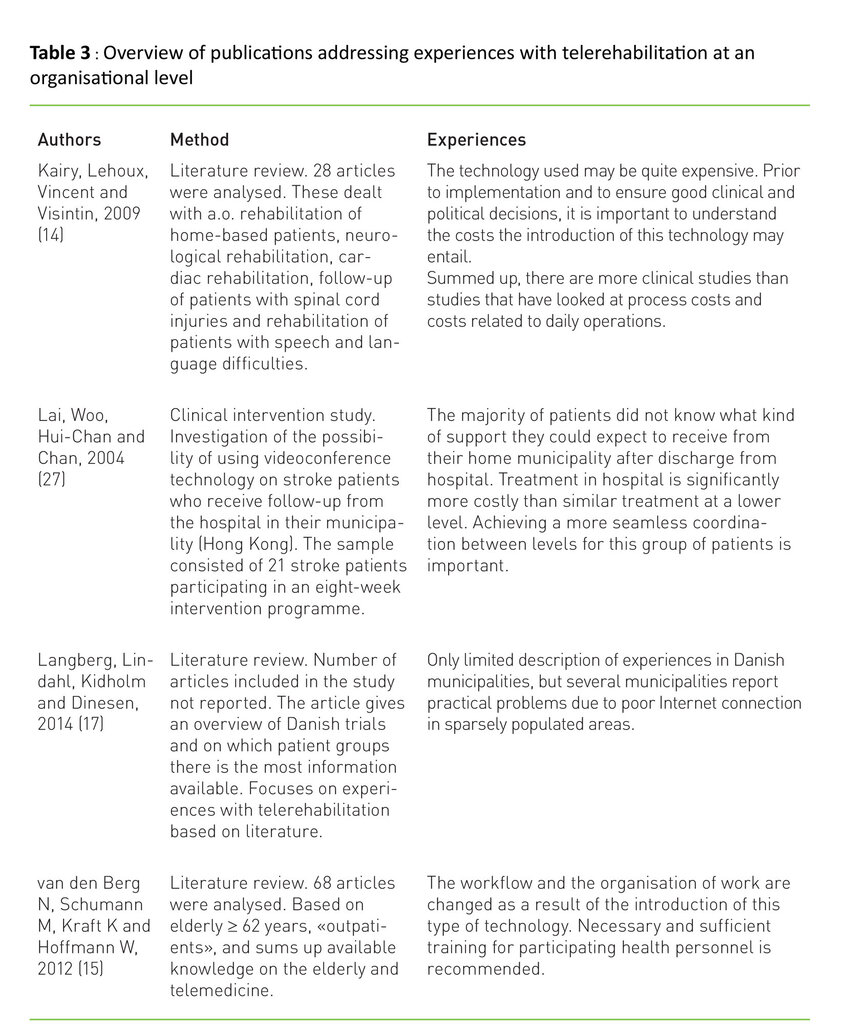

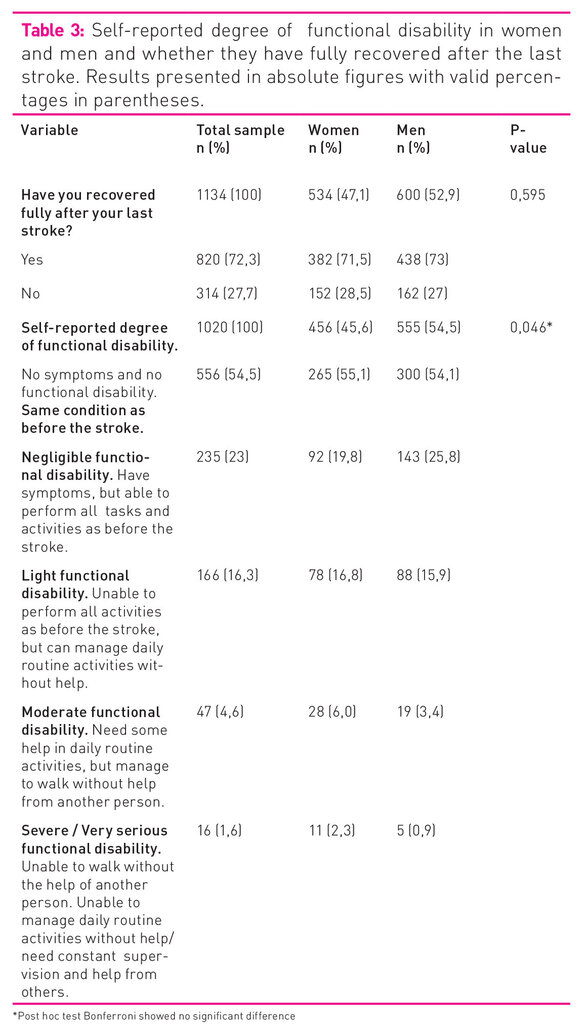

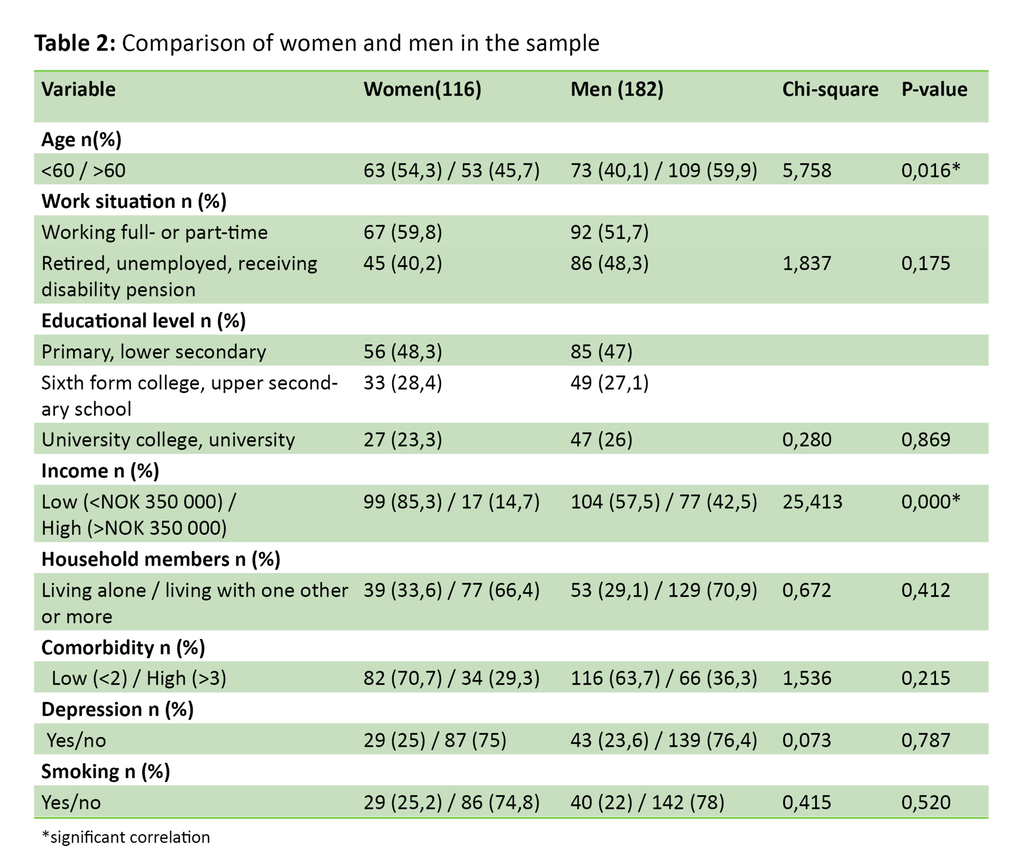

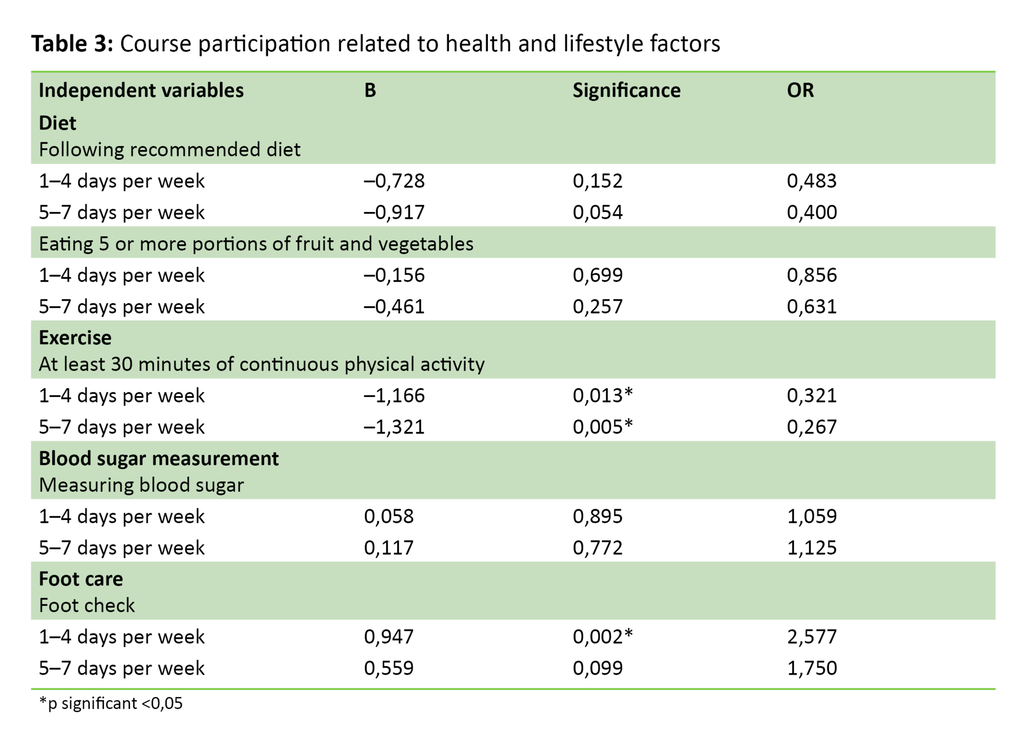

Table 2 compares women and men in the sample with a view to socioeconomic conditions. We find two significant differences between the groups: the men in the study are older than the women, while the women have a lower income. Health behaviour is presented in Table 3, and the results demonstrate that physical activity clearly increases the odds of participating in patient education programmes, where daily physical activity shows an OR equal to 0.4, and physical activity one to four days per week shows an OR equal to 0.32. Foot care (one to four days per week), on the other hand, is associated with an OR equal to 2.6. The findings in Table 3 remain valid when we control for gender.

Discussion

The findings generally indicate a selection bias for group-based self-management programmes, consistent with findings in other countries (7-9). Among those who have not participated in group-based training programmes, we see a tendency towards poorer health behaviour (smoking) and indications of poorer health (more comorbidity). We also see a greater probability that those who participate in training programmes perform some or a significant amount of physical activity. The findings thus support the notion that patients with less appropriate health behaviour participate less, despite the fact that these patients may be said to be those who need help to pursue more health-promoting coping strategies. More women had participated in group-based training, but the fact that the men in the sample are older than the women might partly explain their lower course participation. This accords with findings from other studies (6, 7).

There is reason to believe that the proportion who have participated in group-based self-management programmes in this study is somewhat high in relation to the entire population with type 2 diabetes. Recruitment to the study was undertaken at diabetes outpatient clinics and the personnel at the outpatient clinics are often co-organisers of self-management courses. It may therefore be assumed that personnel at the outpatient clinics actively recruit their patients to courses.

More women use the service

Gender selection bias with a preponderance of women among the participants in group-based self-management programmes is consistent with findings from other studies, which show that women with type 2 diabetes have a greater tendency to use socially interactive training programmes than men (11, 29). We argue that this is because men are often less open about the diagnosis and prefer a more ‘private’ approach to the chronic disease, for example through written information and the internet (29). We have little knowledge as to the reason for these different preferences. However, one study shows that participants on group-based self-management programmes compare themselves to each other and find that some participants appear ‘diligent’ while those that struggle feel like the ‘losers’ of the group (30). A Norwegian study shows that position and affiliation to the group can influence participation in coping groups (31).

Findings on group dynamics may explain why few smokers in the study had participated in group-based self-management programmes. Previous studies show that smokers feel that they are stigmatised and receive unwanted attention in group contexts (32, 33). The group setting around group-based self-management programmes may consequently be perceived to be challenging. Diabetes nurses, GPs and medical specialists will therefore fail to reach all patients, even though they have increased the focus on referring exposed patient groups to group-based self-management programmes. In a qualitative Danish study (34) related to patients who do not wish to participate in such programmes, the patients point to four challenges with the courses, which are associated with the following:

- lack of flexibility in course programmes (too intense and a wish for fixed start times and breaks that are not too rigid)

- teaching methods (a wish for easily understood, hands-on teaching, active participation and a clear focus without too many choices)

- groups that are too large (a wish for small groups of six to seven persons)

- lack of respect from health personnel

The study indicates that low participation in group-based programmes is related to factors in the course design rather than in the patients’ personal traits. This again begs the question of whether investment in group-based self-management programmes has the potential to reach all patient groups. It also raises the question of whether the programme we have today is good enough.

Health and social networks

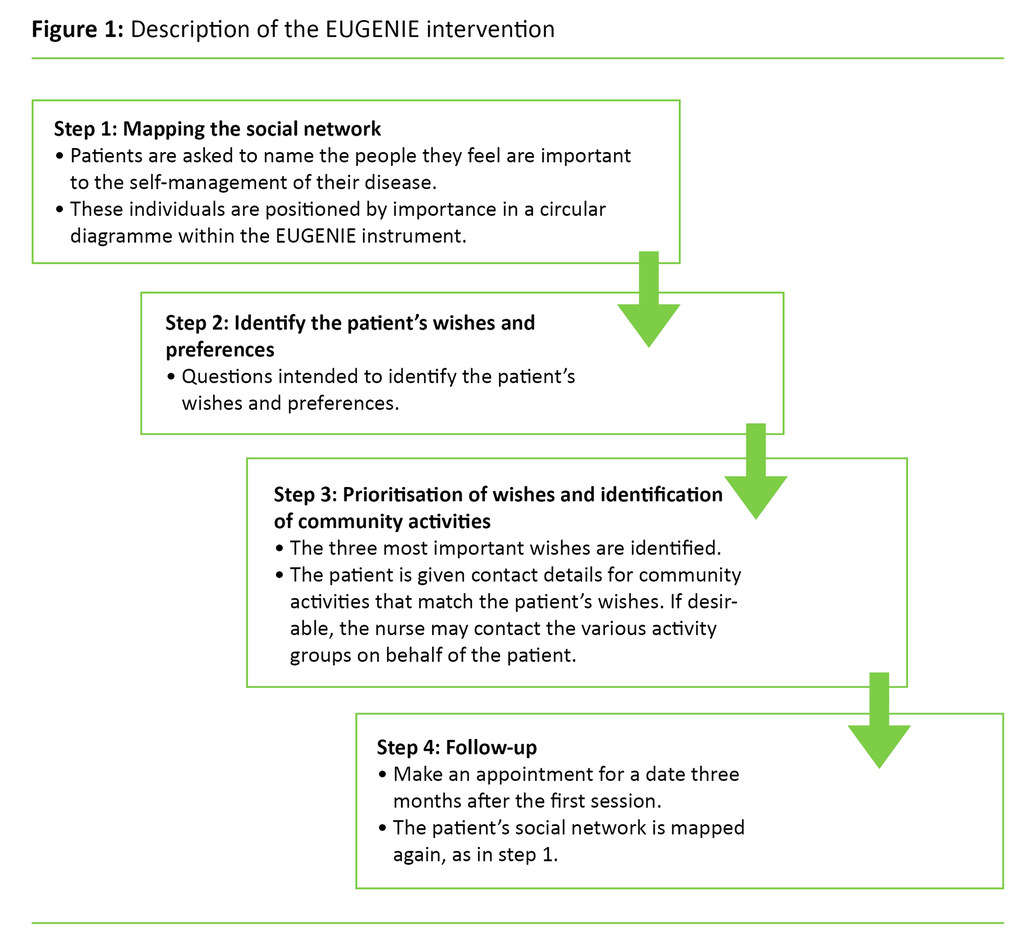

Poor health among economically deprived groups coincides with minimal social networks and few resources in the networks that they have (35). One alternative is therefore to develop interventions to strengthen these networks and the patients’ local community. Attention must shift from the individual and their ability to change and control themselves, to factors beyond the realm of the individual and the individual’s self-control (36). Lifestyle and health are shaped and play out in the social space surrounding the patient. With this understanding, it is possible to look at potential resources in the network and local community as an alternative approach to persons who struggle to cope with type 2 diabetes. Increased social activity beyond the sphere of the health service and the traditional ‘health arenas’ may represent health-promoting interventions for the patient with type 2 diabetes, without the person, the disease and lifestyle changes taking central stage.

As health personnel, we have a responsibility to meet the interests of all groups in the population and test out several approaches in order for health information to reach more people, thereby reducing social inequality in health (37). Investment in patient education in Norway is biased towards group-based self-management programmes, and apparently few objections are raised with regard to the fact that these programmes are not equally suitable for all groups. (38). Our study indicates that there is a need for new and different thinking, and for a focus that extends beyond individual factors in the training programmes.

Broader self-management programmes are suitable for reaching patients who are difficult to recruit to group-based programmes. Moreover, we need more knowledge regarding the wishes of non-participant patient groups. With the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes (1), the lack of self-management programmes constitutes a serious problem with regard to health, long-term complications and increased suffering. At a societal level, an inability to cope and inappropriate health behaviour push up treatment and follow-up costs. Awareness and attention to social health disparities is an important priority area for health policy (15), which unfortunately until now has received little attention in nursing science research.

Methodological assessments

The purpose of the study’s recruitment strategy via outpatient clinics in the specialist health service was to obtain a sample that included patients with a complex disease, who struggle to cope with their type 2 diabetes. In line with the statistics, a poor ability to cope and a complex disease are more frequent in population groups with a low socioeconomic status (24). It is generally difficult to recruit persons with a low economic status to participate in research (39). The picture portrayed by the sample in this study (Table 1) shows that one-quarter are disability pensioners or on sick leave, one-third live alone and have a lower than average income, and one in three report high comorbidity. By way of contrast, the proportion of disability pensioners in the Norwegian population in the age group 18–67 years is 9 per cent (40).

Altogether, 47.7 of study participants reported having a primary/lower secondary education, while the figure is slightly less than 30 per cent of the population among those who are 60 years and over (41). With this comparison, we believe that we can estimate to have obtained a sample that is in line with our intention. However, the representativity of the sample in relation to the total population with type 2 diabetes in Norway is somewhat uncertain. With regard to morbidity, data from the Norwegian Quality Improvement of Laboratory Examinations (NOKLUS) register show that 5.5 per cent have suffered a stroke (42), while the corresponding figure in this study is 5.3 per cent. The NOKLUS register is based on 16 223 Norwegian patients with type 2 diabetes. Other figures are difficult to compare. Although the percentage that has suffered a stroke is approximately the same as the percentage in the NOKLUS population, we cannot guarantee the representativity of the sample. Caution should therefore be exercised in making any generalisations.

The health condition of the informants in the study is based on self-reporting, which may represent a weakness in the study. Holseter and colleagues, however, find that self-reporting yields valid data when presenting health disparities, also when different social groups are compared (43). There are few respondents with an immigrant background in the study, which is probably attributable to the fact that the questionnaire was in Norwegian. The diabetes nurses who did the recruitment for the study confirmed that informants with another cultural background did not manage to complete the questionnaire due to language difficulties. The decision not to translate the questionnaire to minority languages was a joint decision by EU-WISE and was related to finances. We have thereby not included participants with another cultural background, who represent an important and exposed group with regard to type 2 diabetes, socioeconomic status and health behaviour (22). This constitutes a weakness in our study.

Conclusion

The results show that more than half of the informants have not participated in group-based self-management programmes, and that there is a selection bias in patient education programmes among people with type 2 diabetes. Participation is higher among women and persons with a higher education, while smokers and persons with high comorbidity have a lower participation rate. There are also higher odds of participation among patients who are physically active and therefore have better health behaviour. These findings are consistent with those from international studies, which show that certain groups fail to benefit from group-based self-management programmes on which there is a considerable focus today. Our study highlights a need for more knowledge on which programmes may suit those groups of patients who do not find existing ones attractive. The study also indicates a need for more targeted recruitment to existing programmes. In order to help equalise social health disparities, it seems to be important to pursue approaches that go beyond programmes that are clearly oriented towards the individual, thereby reaching more groups in the population.

References

1. Midthjell K, Lee C, Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Holmen T, Hveem K. Obesity and type 2 diabetes still increase while other cardiovascular disease risk factors decline. The HUNT Study, Norway. Obesity reviews 2010;11 (suppl):58.

2. Blakeman T, Bower P, Reeves D, Chew-Graham C. Bringing self-management into clinical view: a qualitative study of long-term condition management in primary care consultation. Chronic Illness 2010;6:136–50.

3. Hvinden K. Etablering av lærings- og mestringssentra – historie, grunnlagstenkning, innhold og organisering. In: Lerdal A, Fagermoen MS (eds.). Læring og mestring – et helsefremmende perspektiv i praksis og forskning. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 2011. s. 48–62.

4. Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Nøstberg A, Steinsbekk A, Vist G. Effekt av gruppeundervisning i pasient- og pårørendeopplæring: en oppsummering av systematiske oversikter. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten, 2011.

5. Deakin T, McShanes C, Cade J, Williams R. Group based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Databases of Systematic Reviews 2009;2.

6. Steinsbekk A, Rygg L, Lisulo M, Rise M, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Health Services Research 2012;12:213.

7. Mielck A, Reitmeir P, Rathmann W. Knowledge about diabetes and participation in diabetes training courses: The need for improving health care for diabetes patients with low SES. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2006;114:240–8.

8. Cauch-Dudek K, Victor J, Sigmond M, Shah B. Disparities in attendance at diabetes self-management education programmes after diagnosis in Ontario, Canada: a cohort study. BMC Public Health 2013;13(85).

9. Schäfer I, Küver C, Gedrose B, von Leitner E, Treszl A, Wegscheider K et al. Selection effects may account for better outcomes of the German Disease Management Program for type 2 diabetes. BMC Health Services Research 2010;31(10):351.

10. Graziani C, Rosenthal M, Diamond J. Diabetes education program use and patient-perceived barriers to attendance. Family Medicine 1999;31(5):358–63.

11. Mathew R, Gucciardi E, De Melo M, Barata P. Self-management experiences among men and women with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative analysis. BMC Family Practice 2012;13:122–35.

12. Jensen A. Sosiale ulikheter i bruk av helsetjenester. En analyse av data fra Statistisk sentralbyrås levekårsundersøkelse om helse, omsorg og sosial kontakt. Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå, 2009.

13. Vikum E, Bjørngaard J, Westin S, Krokstad S. Socioeconomic inequality in health care utilization over 3 decades; the HUNT study. European Journal of Public Health 2013;23(6):1003–10.

14. Abel T. Cultural capital and social inequality in health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:e13.

15. St.meld. nr. 20 (2006–2007). Nasjonal strategi for å utjevne sosiale helseforskjeller. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet.

16. WHO. Social determinants of health: the solid facts. 2. ed. København: World Health Organization, 2003.

17. Lien N, Kumar B, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Klepp K, Wande l. Assessing social differences in overweight among 15- to 16-year-old ethnic Norwegians from Oslo by register data and adolescent self-reported measures of socio-economic status. International Journal of Obesity 2007;31(1):30–8.

18. Tverdal A. Forekomsten av fedme blant 40–42-åringer i to perioder. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2001;121:667–72.

19. Lund K, Lund M. Røyking og sosial ulikhet i Norge. Tidssk Nor Lægeforen 2005;5:560–3.

20. Øvrum A, Gustavsen G, Rickertsen K. Age and socioeconomic inequalities in health: Examining the role of lifestyle choices. Advances in Life Course Research 2014;19:1–13.

21. Øvrum A. Socioeconomic status and lifestyle choices: evidence from latent class analysis. Health Econ 2011;20:971–84.

22. Jenum A, Diep L, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Holme I, Kumar B, Birkeland K. Diabetes susceptibility in ethnic minority groups from Turkey, Vietnam, Sri Lanka and Pakistan compared with Norwegians – the association with adiposity is strongest for ethnic minority women. BMC Public Health 2012;1(12):150.

23. Jenum A, Holme I, Graff-Iversen S, Birkeland K. Ethnicity and sex are strong determinants of diabetes in an urban western society. Diabetologia 2005;48:435–9.

24. Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, Moradi T, Sidorchuk A. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:804–18.

25. Hewitt S, Graff-Iversen S. Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes in disability pensioners aged 40–42: A cross-sectional study in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2009;37:280–6.

26. Koetsenruijter J, van Lieshout J, Vassilev I, Portillo M, Serrano M, Knutsen I et al. Social support systems as determinants of self-management and quality of life of people with diabetes across Europe: study protocol for an observational study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2014;12(29).

27. Toobert D, Hampson S, Glasgow R. The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000;23:943–50.

28. Gjersing L, Caplehorn JR, Clausen T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2010;10(13).

29. Gucciardi E, Wang S, DeMelo M, Amaral L, Stewart D. Characteristics of men and women with diabetes: observations during patients’ initial visit to a diabetes education centre. Can Fam Physician 2008;Febr 54(2):219–27.

30. Rogers A, Gately C, Kennedy A, Sanders C. Are some more equal than others? Social comparison in self-management skills training for long-term conditions. Chronic Illness. 2009;5(4):305–17.

31. Sandaunet A-G. The challenge of fitting in: non-participation and withdrawal from online self-help group for breast cancer patients. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008;30(1):131–44.

32. Stuber J, Galea S, Link B. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Soc Sci Med 2008;67(3):420–30.

33. Sæbø G. «Vi blir en sånn utstøtt gruppe til slutt ...» Røykeres syn på egen røyking og denormaliseringsstrategier i tobakkspolitikken. Oslo: SIRUS-rapport 3/2012.

34. Torenholt R, Varming A, Engelund G, Vestergaard S, Møller BL, Pals RA. Willaing I. Simplicity, flexibility, and respect: preferences related to patient education in hardly reached people with type 2 diabetes. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;Nov 5(9):1581.

35. Gele A, Harsløf I. Types of social capital resources and self-rated health among the Norwegian adult population. International Journal of Equity in Health 2010;9(8).

36. Vassilev I, Rogers A, Sanders C, Kennedy A, Blickem C, Protheroe J et al. Social networks, social capital and chronic illness self-management: a realist review. Chronic Illness 2011;7(1):60–86.

37. Gopinathan U, Iversen J. Hva kan helsepersonell gjøre med sosiale helseforskjeller? Tidssk Nor Lægeforen 2011;131:1560–2.

38. Solberg H, Steinsbekk A, Solbjør M, Granbo R, Garåsen H. Characteristics of a self-management support programme applicable in primary health care: a qualitative study of users’ and health professionals’ perceptions. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:562.

39. Honningsvåg L, Linde M, Håberg A, Stovner L, Hagen K. Does health differ between participants and non-participants in the MRI-HUNT study, a population based neuroimaging study? The Nord-Trøndelag health studies 1984–2009. BMC Medical Imaging 2012;12(23).

40. Grebstad U, Hetland A. Uføretrygd og sosialhjelp - to ulike formål. Samfunnsspeilet. 2014;5:47–53.

41. Statistisk sentralbyrå. Befolkningens utdanningsnivå. Available at: www.ssb.no/utniv (Downloaded 29.06.2016). 2015.

42. Løvaas K, Madsen T, Cooper J, Thue G, Sandberg S. Norsk diabetesregister for voksne. Årsrapport for 2014 med plan for forbedringstiltak. Bergen: 2015. Available at: http://www.noklus.no/Portals/2/Diabetesregisteret/Arsrapport%20Norsk%20diabetesregister%20for%20voksne%202014.pdf

43. Holseter C, Dalen J, Krokstad S, Eikemo T. Selvrapportert helse og dødelighet i ulike yrkesklasser og inntektsgrupper i Nord-Trøndelag. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2015;5(135):434–8.

Group-based self-management programmes make it easier to cope with the disease. However, half of all patients decline to participate in such programmes.

Background: Group-based self-management programmes are arranged for patients with type 2 diabetes to increase coping skills and prevent complications of type 2 diabetes. However, it is uncertain whether the programmes are attractive to all groups of patients. International studies show that patients who fail to comply with recommendations on lifestyle and have a low socioeconomic status are under-represented in group-based self-management programmes.

Objective: The study examines a Norwegian sample of type 2 diabetes patients and aims to investigate the percentage who have attended group-based self-management programmes, and characteristics of participants and non-participants.

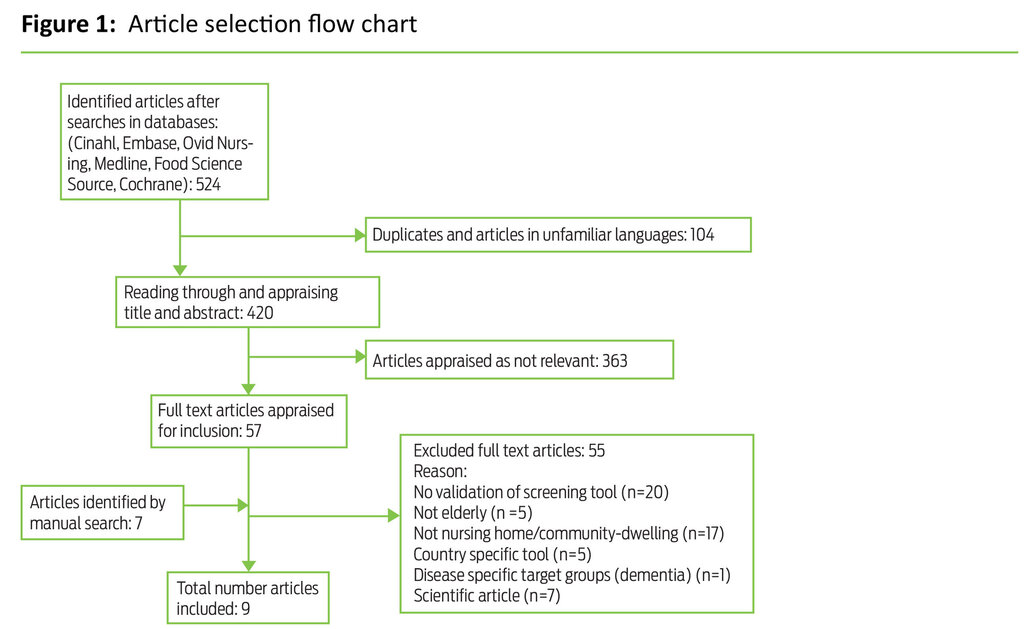

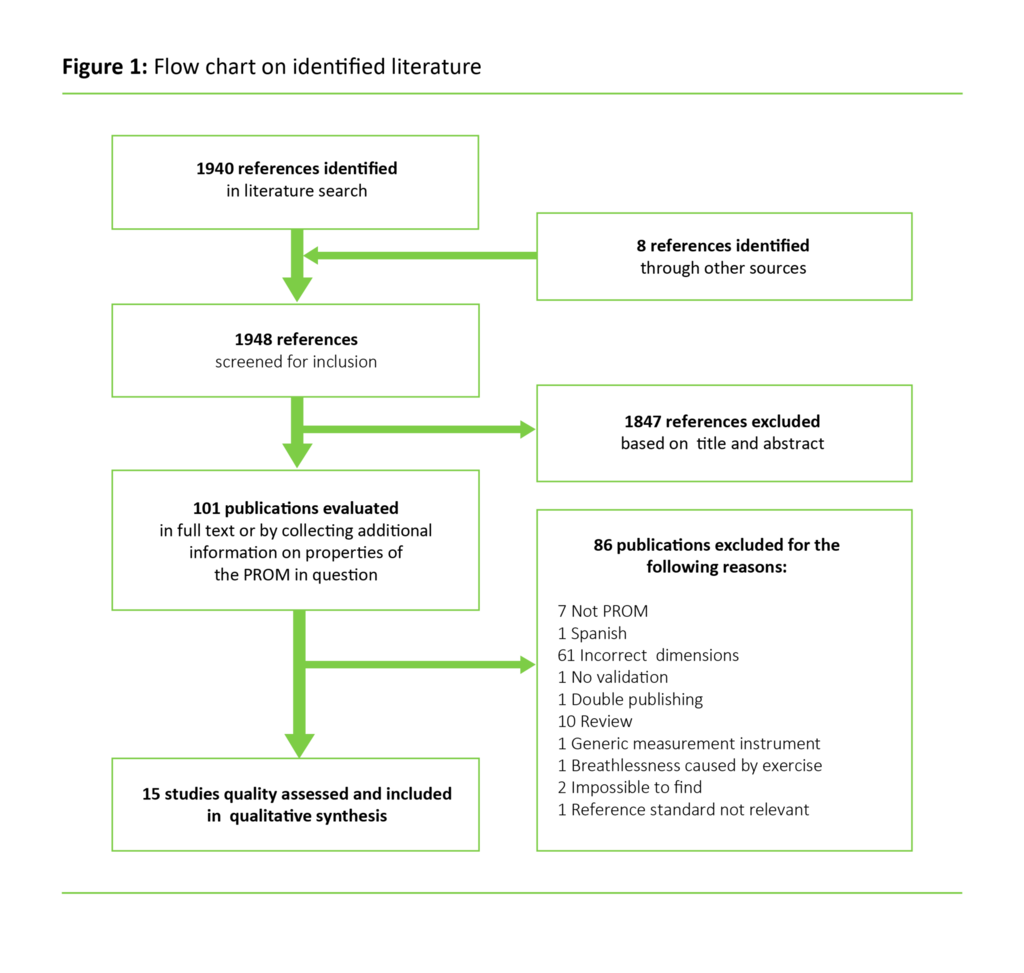

Method: This is a descriptive cross-sectional study for which 298 patients with type 2 diabetes completed a questionnaire (84.2% response rate). Chi-square test and logistic regression analysis were used to compare participants and non-participants.

Result: In the study, 61% of participants are men and 39% are women, and the mean age is 60 years. Altogether 38% of the respondents had participated in group-based self-management programmes. Significant differences emerged when comparing participants with non-participants. Among participants, the majority were women and persons with a higher education, while smokers were in the majority among non-participants. Physical activity was strongly correlated with participation.

Conclusion: The findings reveal selection bias in group-based self-management programmes and indicate the need to develop and test alternative programmes to reach more groups of patients in the population.