The organization of 22 care pathways in the Western Norway Regional Health Authority

The Norwegian health service faces various challenges related to coordination, the transfer of information and undesired variation (1). Poor quality and undesired events can lead to injury or early death (2). The challenges posed by the organization of the care trajectory in the health system (3) mean that more knowledge is needed on quality and safety.

The introduction of 28 care pathways within cancer treatment (4) has once again put a spotlight on the standardization of care pathways as a means of improving the quality of the health service. Internationally, standardized care pathways are increasingly being used as a tool for improving the quality of diagnostics, treatment and follow-up of hospital patients (5).

Confusing terminology

The diverse terminology used in standardized care processes is confusing. ‘ Behandlingsline’ and ‘ strukturert/standardisert pasientforløp’ are used in Norwegian, while English synonyms include ‘care pathways’, ‘clinical pathways’ and ‘critical pathways’ (6-8). In principle, it is important to make a distinction between when a ‘care pathway’ is used as an intervention, i.e. ‘standardization’, aimed at improving the quality of work processes, and when referring to the care trajectory from measure to measure, unit to unit, or between levels in the health service. The aim of standardizing care processes is to improve the quality of treatment processes (8–11).

The European Pathway Association (E-P-A) defines the standardization of care processes into ‘care pathways’ as ‘a methodology for the mutual decision making and organization of care for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period’ (12). This method is used to define goals and make decisions on what measures to include in the treatment. The measures included in the treatment should reflect evidence, best practice and the expectations of the patient. Health care personnel must facilitate and coordinate the communication, roles and order of work in the interdisciplinary team. In addition, it is important to document and follow up the improvement work systematically. The perspectives of the user and their family play a key role in the E-P-A’s definition of a standardized care pathway.

Towards a standardized care pathway

A good first step in the standardization of a treatment process is to develop a written procedure or written guidelines (10). However, improving the service requires the personnel working with the relevant patient group to adhere to such written specifications. In the efforts to standardize care processes, the interdisciplinary team (13) takes a targeted and systematic approach to methodology from the field of quality (10, 11, 14, 15). It is shown that this way of improving the organization of processes leads to a better patient outcome, a lower risk of undesired events, better documentation (11, 16-19), a better working environment and a lower risk of burnout (20, 21).

However, the methodology has also been criticized for not having measurable effects for all patient groups, and whether the cost of developing standardized care pathways justifies their use is a matter of debate (19, 22). In Norway, there is still a need for research on the standardization of care processes. Earlier studies in this country have shown that staff find that such interventions change practices, that the cooperation between contributors improves (23), treatment time is reduced (24), the number of operations performed increases (25), and the outcome for patients is better (26, 27).

Objectives of the study

Using the Care Process Self-Evaluation Tool (CPSET), we asked interdisciplinary teams in the specialist health service about their experiences with the organization of the treatment for specific patient groups. The aim of this sub-study was to map the staff’s perceptions of the degree to which the organization was patient focused, how well the treatment for the patient groups was coordinated, how well the communication with patient and family worked, how well the collaboration with primary care worked, and whether the standardization of care processes was followed up. A further goal was to examine whether the staff considered the organization to be better in the care processes that were standardized using a written clinical procedure compared to pathways without such procedures.

Method

Design and participants

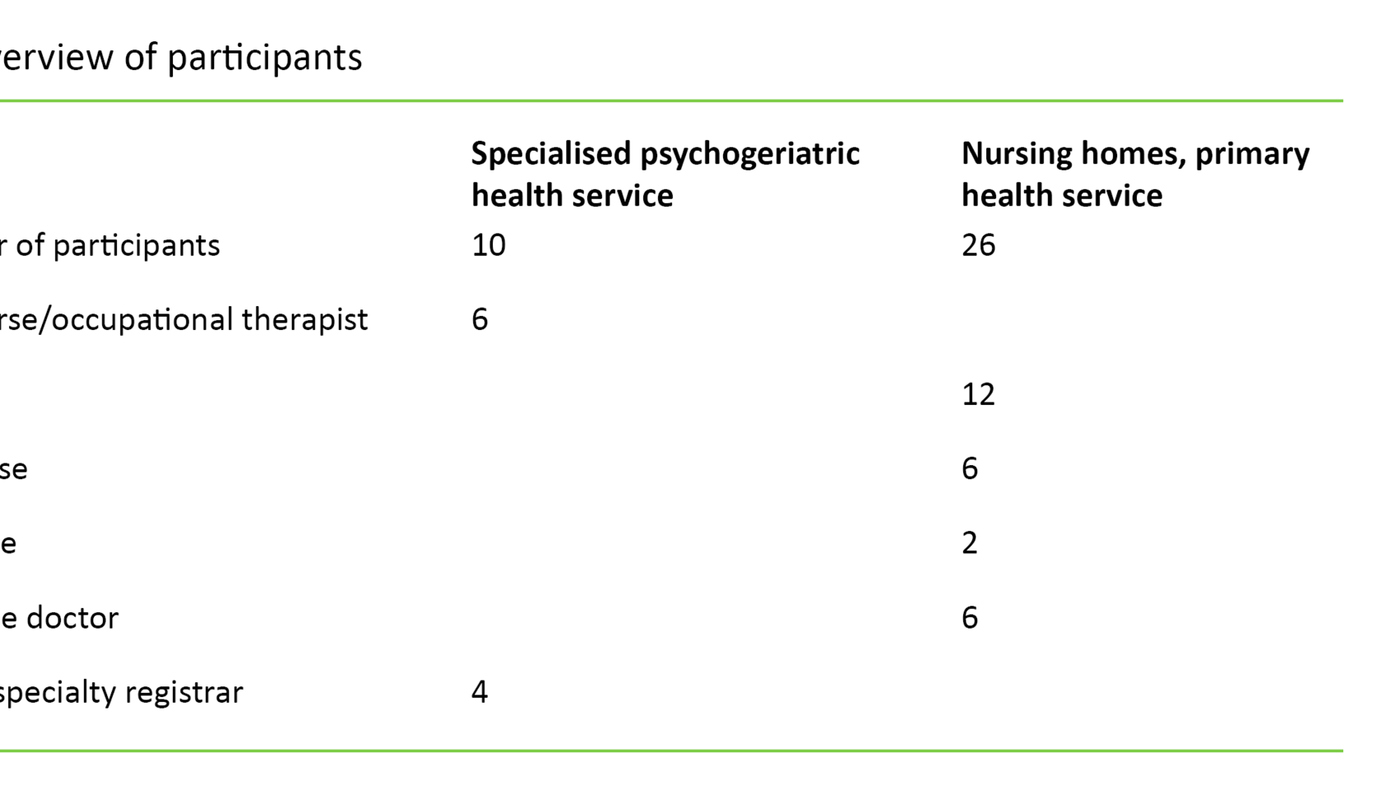

In this study, staff took part from a total of six somatic hospitals and six psychiatric units in three of the four health enterprises in Western Norway Regional Health Authority: Førde Hospital Trust, Bergen Hospital Trust and Fonna Hospital Trust. The units included varied considerably in size, and both urban and more rural institutions participated. Participants were recruited at the care process, team and individual level. The goal was to include care processes within a wide range of conditions. Care processes were selected after asking senior managers in the health enterprises if units in their organization could provide data from specific care processes. In consultation with researchers and professionals, the managers selected relevant care processes and designated a contact person for each.

Care processes were defined according to the patient group, and were based on diagnosis or clinical images. Each individual care process should be typical of and represent a large share of the patients in the units, such as a ‘tonsillectomy’ patient in an ear, nose and throat unit. The contact persons knew both the patient group and the staff who were involved in their treatment. These contact persons provided a list of staff who made up the interdisciplinary team responsible for the treatment of patients in the selected care process. The following inclusion criteria were applied to the members of the team:

- All occupation groups that were involved in the treatment of the patient group.

- The respondents should have daily contact with the relevant patient group.

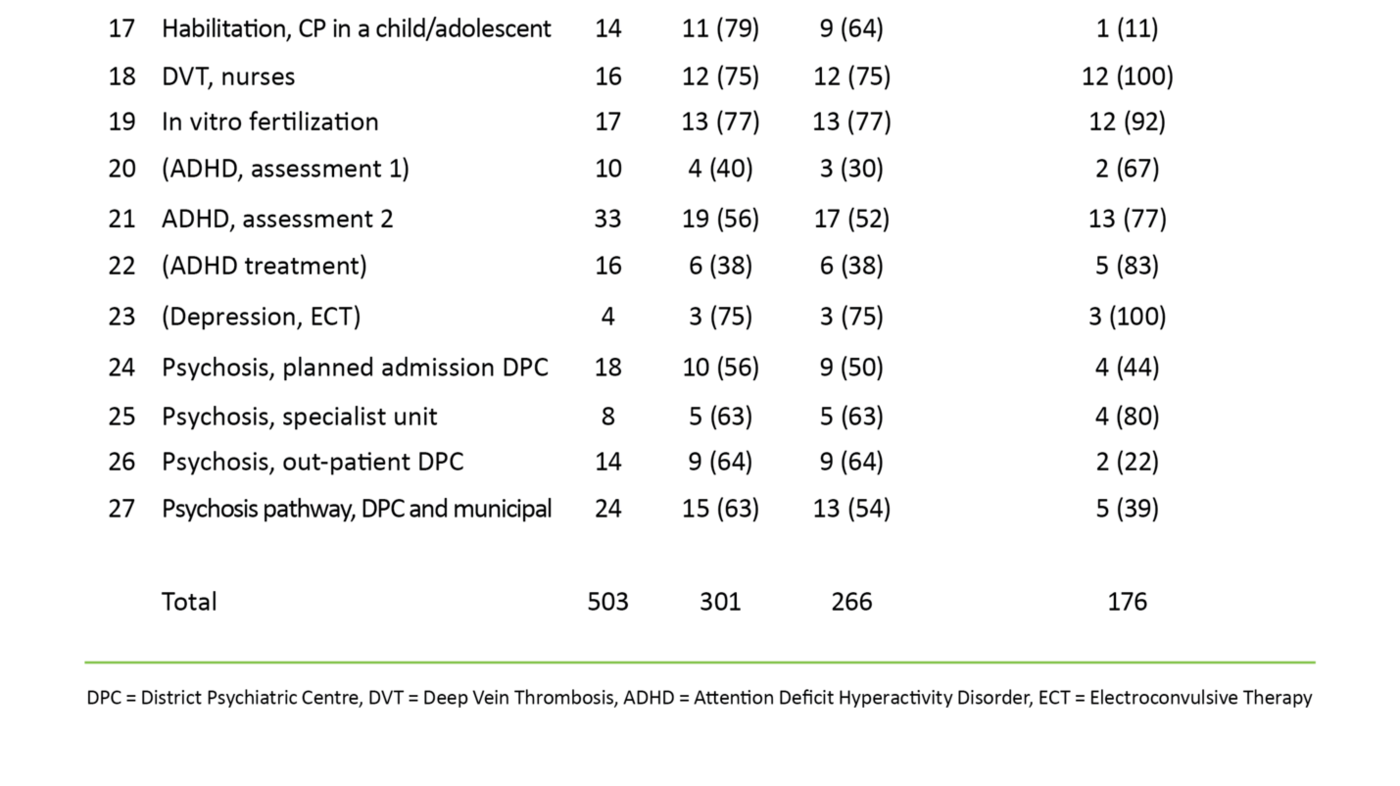

We then sent information about the project and a link to the questionnaire in Corporater Surveyor v.3.3 (Corporater Inc.) in an e-mail to 503 selected health personnel in 27 teams in 2012 and 2013.

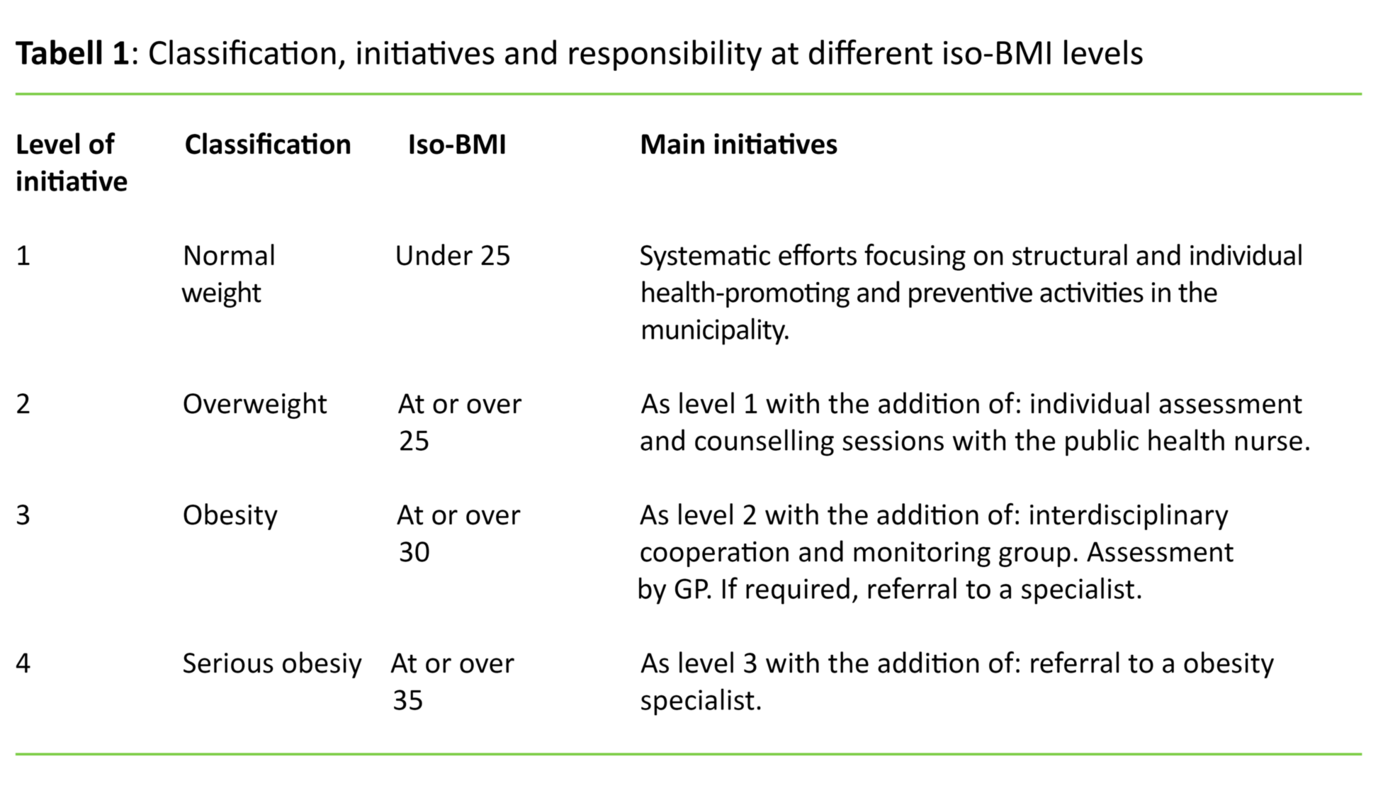

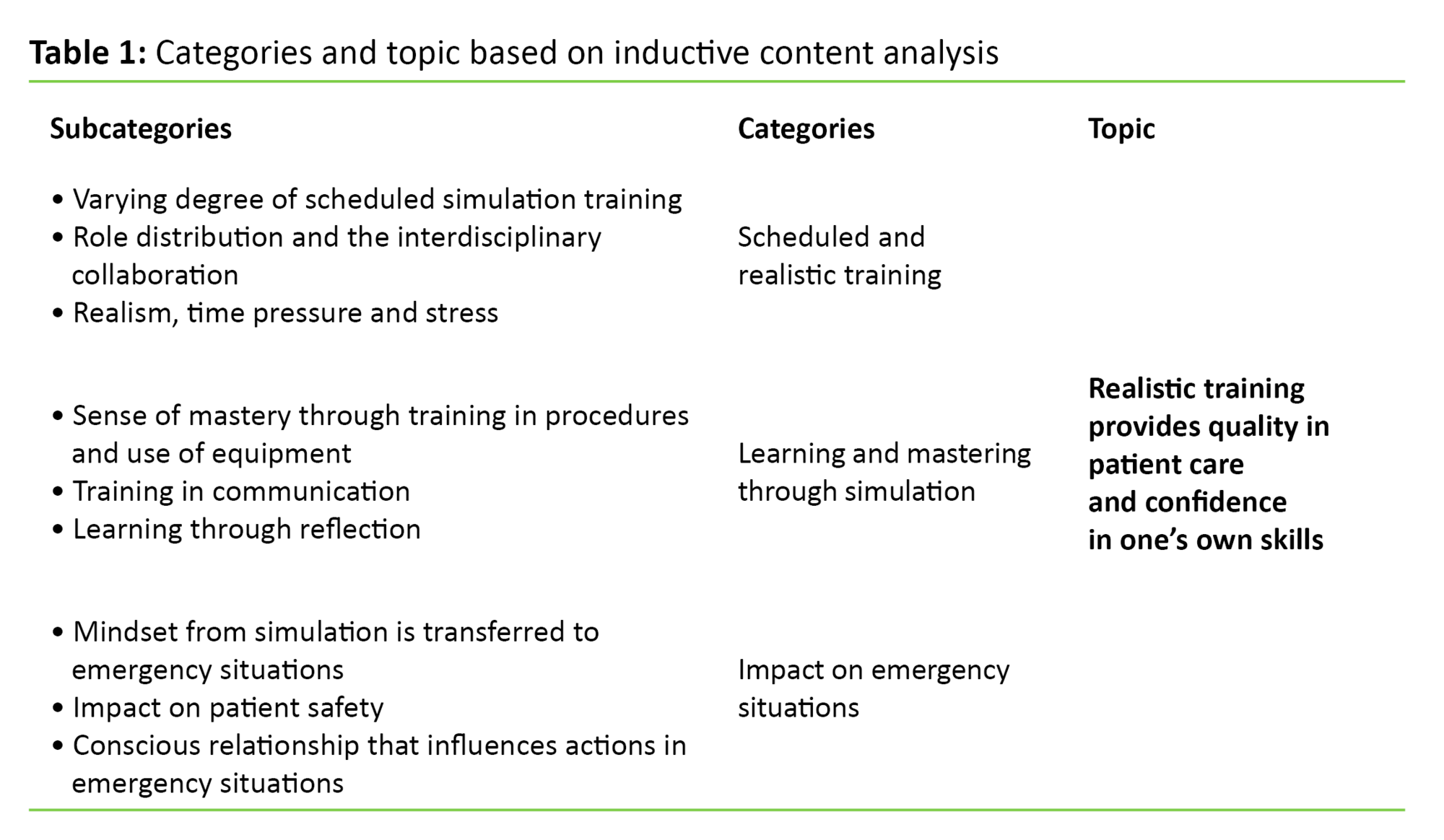

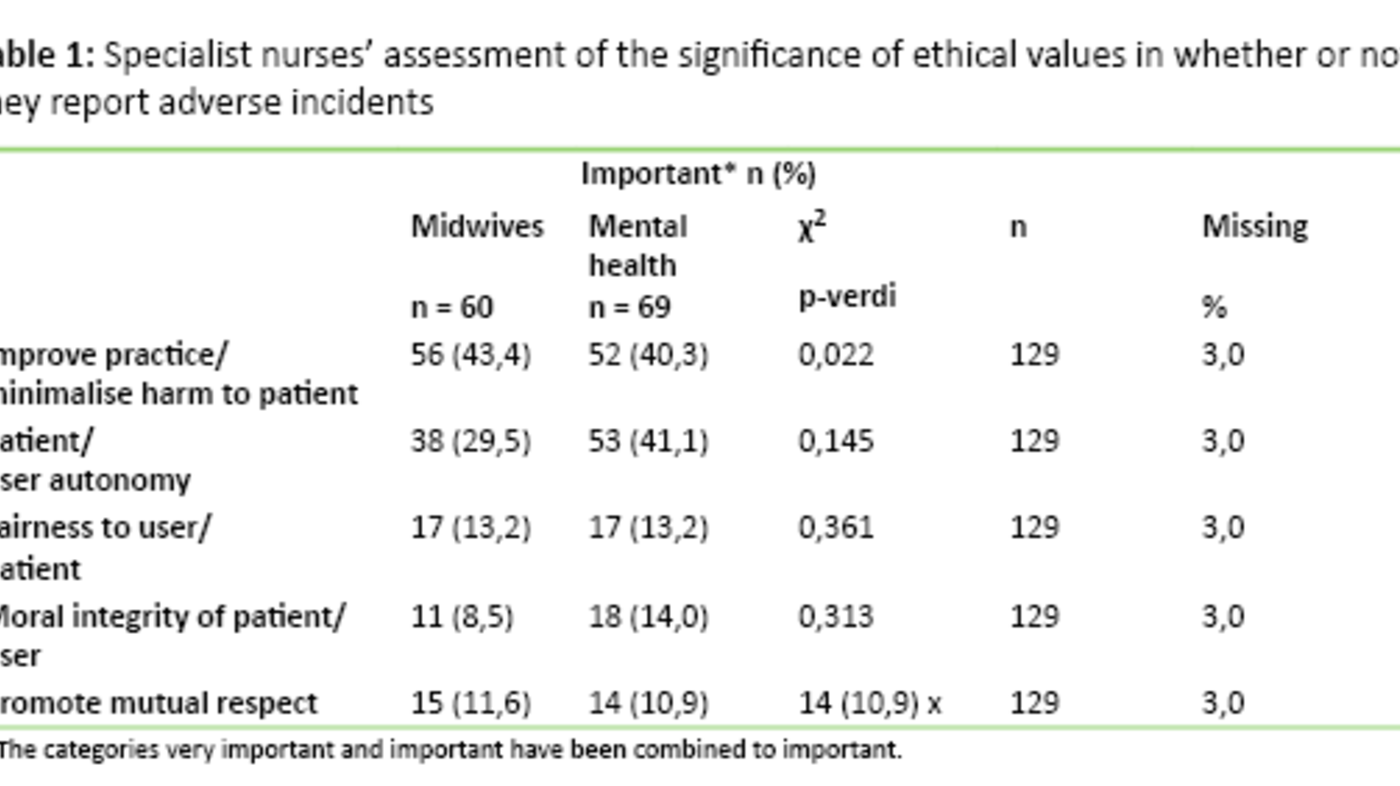

At the start of the questionnaire, the patients were instructed on which patient group they should relate their answers to. For example, the respondents in the units where the care process for COPD was to be evaluated were instructed to answer the CPSET questions based on their experiences with the organization of treatment for patients with COPD in their units. A reminder was sent out to those who were invited to take part. The responses received were deidentified. In order to protect the anonymity of respondents, the ‘key’ that linked their identity to the analysis file was stored by Western Norway Regional Health Authority’s ICT service provider, Helse Vest IKT, in line with the regulations. The project was approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services, now known as the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). Table 1 shows the participating care processes:

The CPSET questionnaire

The CPSET is a questionnaire developed by researchers at the Catholic University of Leuven (KU Leuven) in Belgium, and is validated in the Belgian-Dutch Clinical Pathway Network in collaboration with the E-P-A (28-30). Patients, health care managers and a variety of professionals helped to develop the instrument (29). The questionnaire can be useful both for mapping the organization of specific work processes in a team perspective and for evaluating work aimed at improving the quality of processes in hospitals and research.

The form is used in several European countries (30, 31), and is currently being tested in France, Italy, Ireland and Germany. The CPSET measures how well work processes performed by interdisciplinary teams for specific patient groups in hospitals are organized, and asks respondents to give their opinions on 29 statements covering five conceptual areas (29, 30). The areas are represented by the following sub-scales:

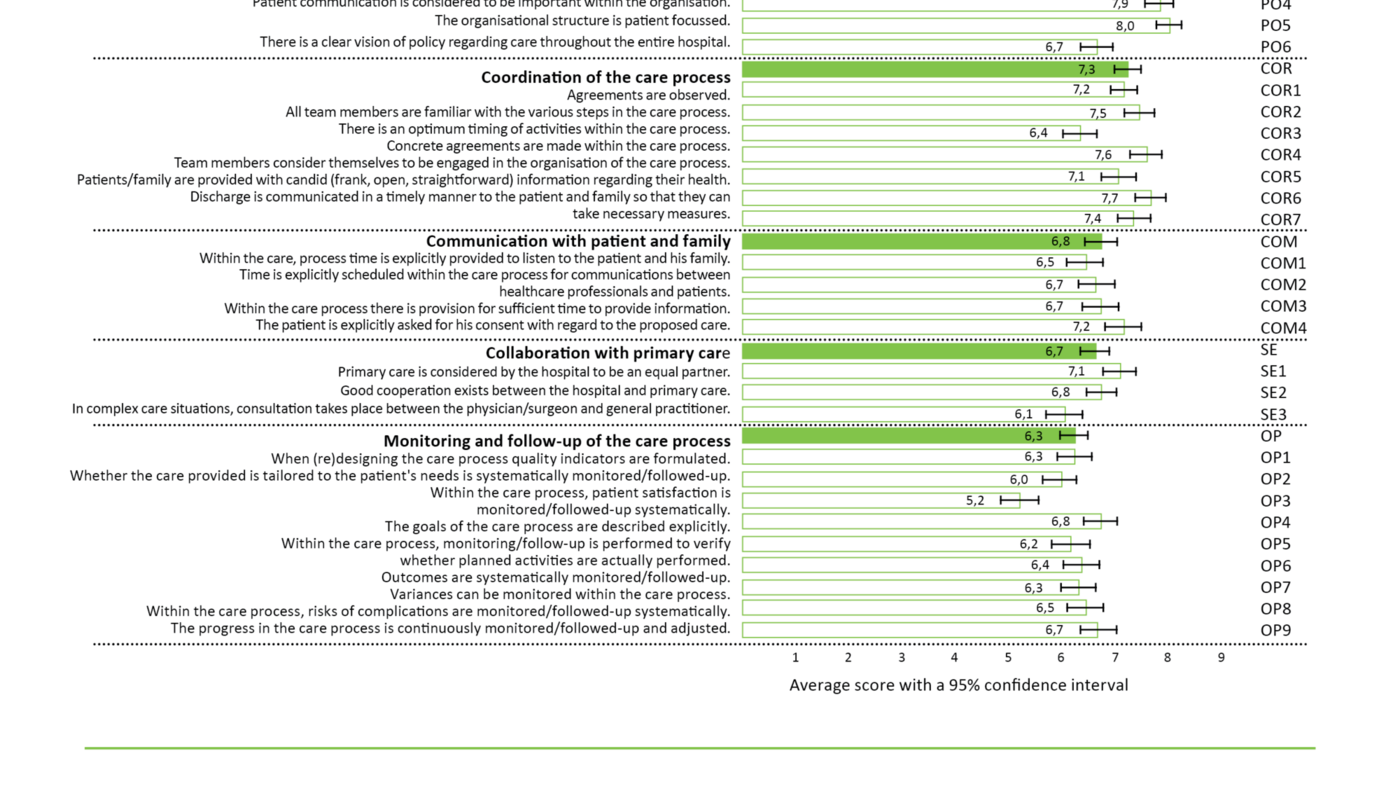

- Patient-focused organization (P01–PO6)

- Coordination of the care process (COR1–COR7)

- Communication with patient and family (COM1–COM4)

- Collaboration with primary care (SE1–SE3)

- Monitoring and follow-up of the care process (OP1–OP9)

The health care worker gives a score for each statement using an ordinal scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means ‘totally disagree’ and 10 means ‘totally agree’.

An authorized translation agency translated the CPSET from the original Flemish to Norwegian. As a pilot, we first tested the translated version using ten professionals in the specialist health service (32). These came from various disciplines at a medium-size hospital in Western Norway Regional Health Authority. The feedback from the professionals suggested that the understanding of key terms, such ‘ behandlingsprosess’, ‘ behandlingsline’, ‘ behandlingsforløp’ and ‘ pasientforløp’, which are translations of ‘care process’, ‘care pathway’, and ‘clinical pathway’, varied a lot, while the understanding of ‘written clinical procedure for the care process’ was mostly good.

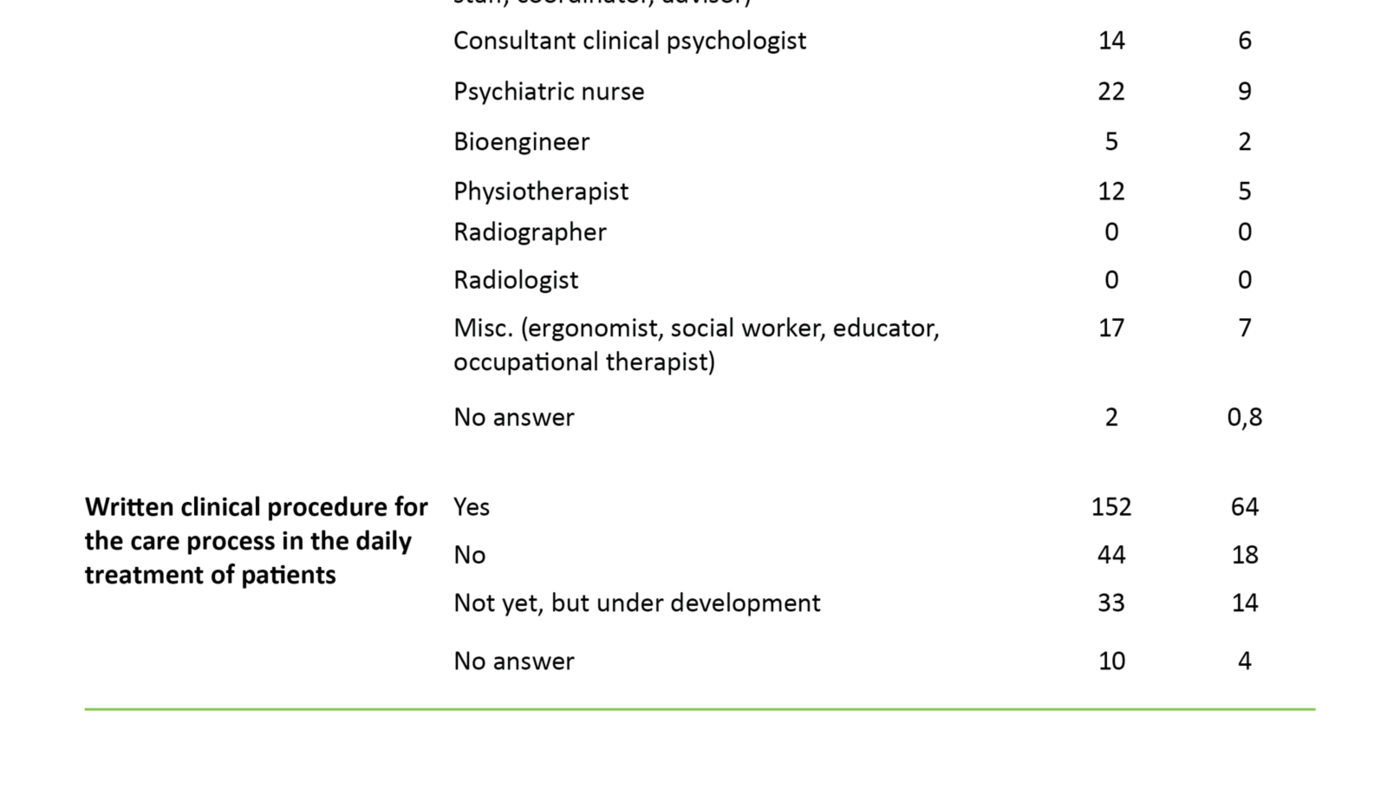

We therefore chose to translate ‘care pathways’ that referred to interventions aimed at standardizing the treatment process as ‘written clinical procedure for the care process’. In the study, we asked the respondents to answer the following questions: ‘Is there a written clinical procedure for the care process in the daily treatment of patients?’, and ‘If the procedure description/care pathway is being developed or currently in use, how many months has this been the case?’

Statistical approach

Because we had data from a variety of care processes, we chose to show the CPSET scores within each care process descriptively by giving an average, with upper and lower limits for a 95 per cent confidence interval (CI). This enabled us to see the pattern in the CPSET scores without having to conduct statistical tests with many comparisons. We wanted to test the disparities in the CPSET sub-scales and overarching scales between the groups who responded ‘yes’, ‘being developed’ or ‘no’ to the question of whether a written clinical procedure was used in the relevant care process. For this we used the Kruskal-Wallis test, with follow-up tests between sets of two groups. The tests were done in SPSS version 20 and were two-tailed with p-level 0.05.

Results

Response rate and valid care processes

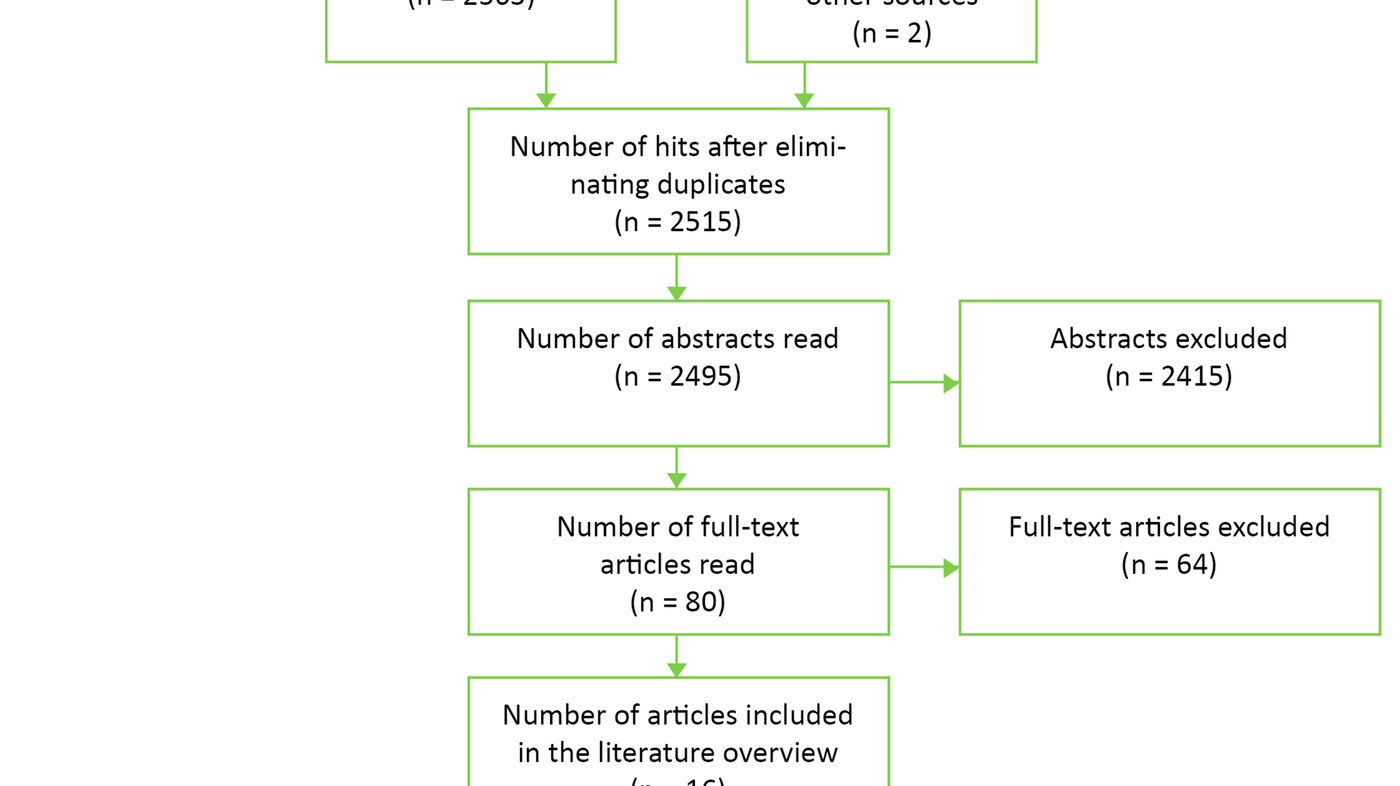

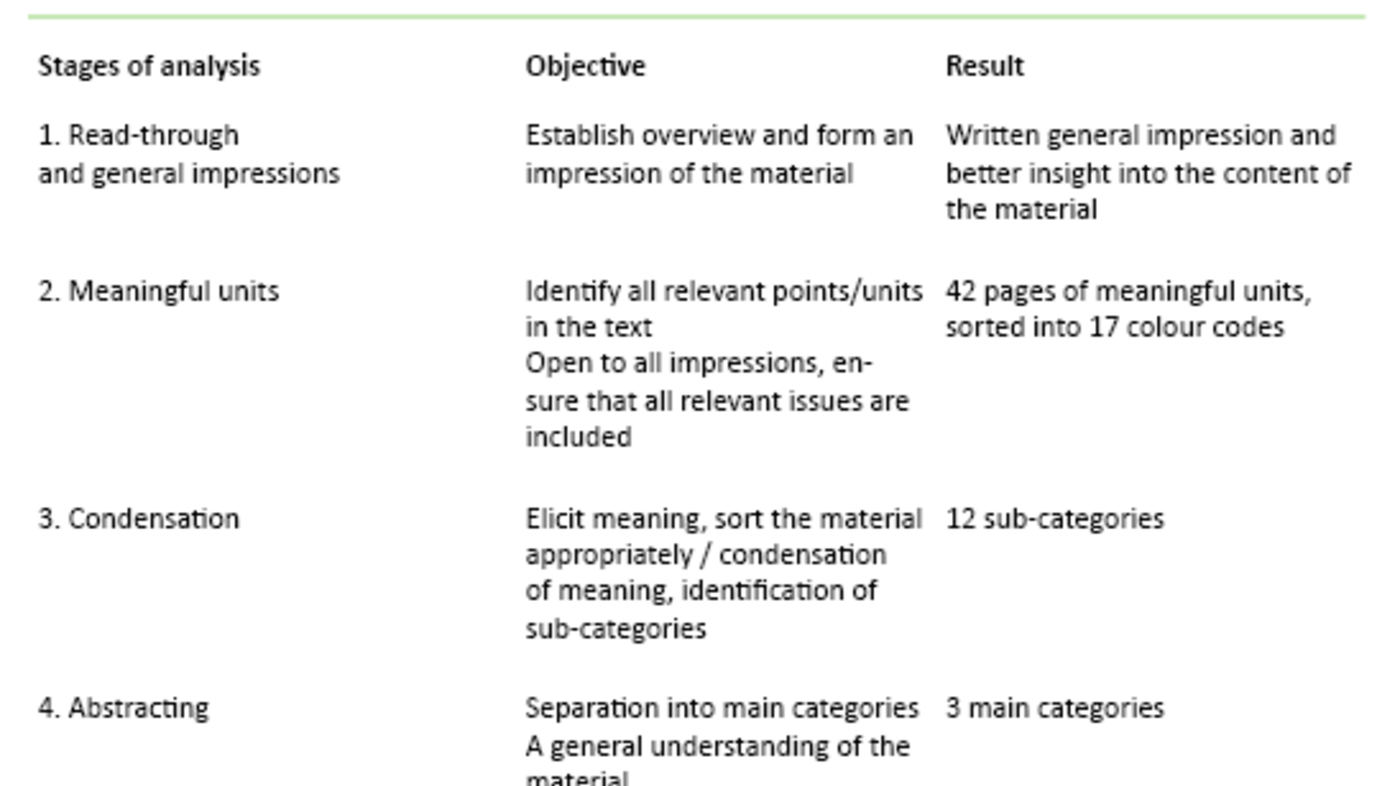

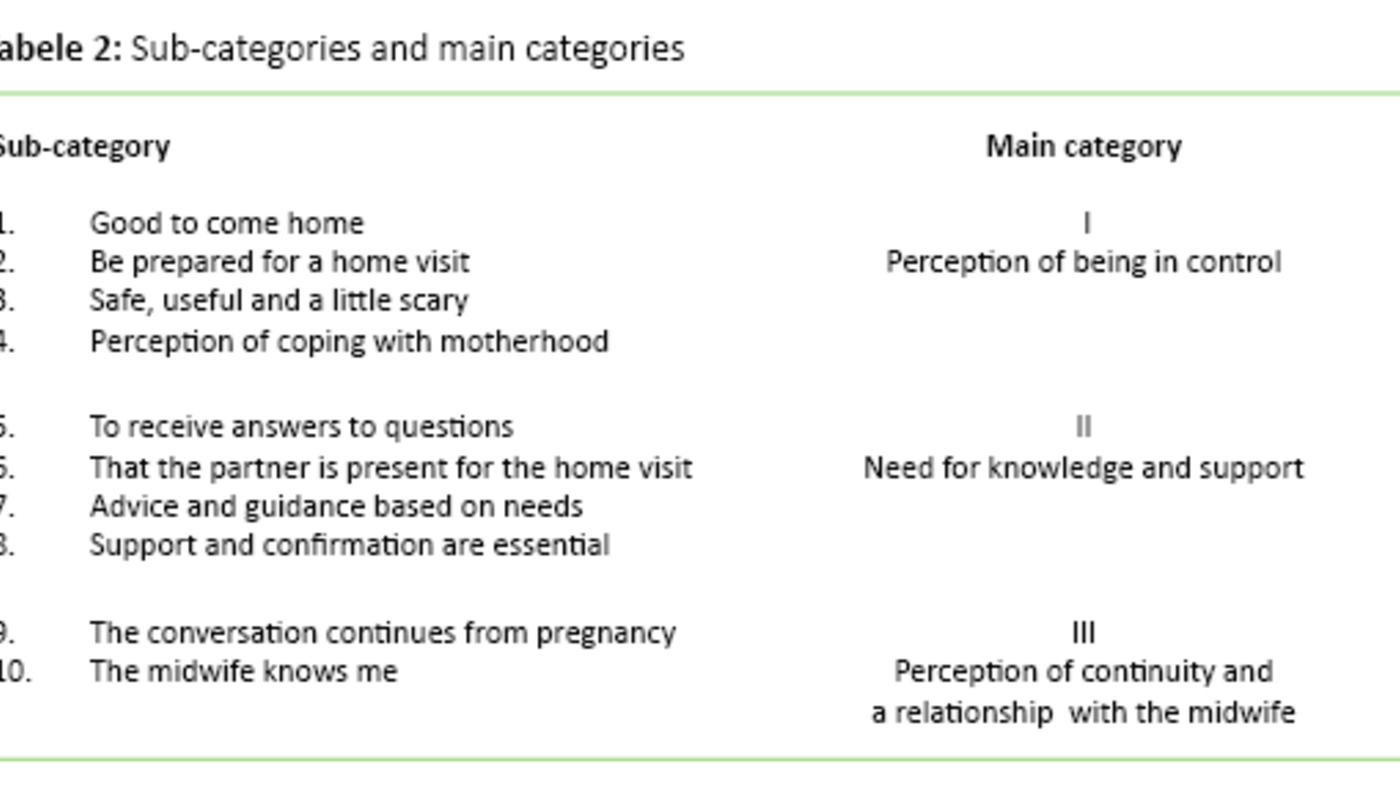

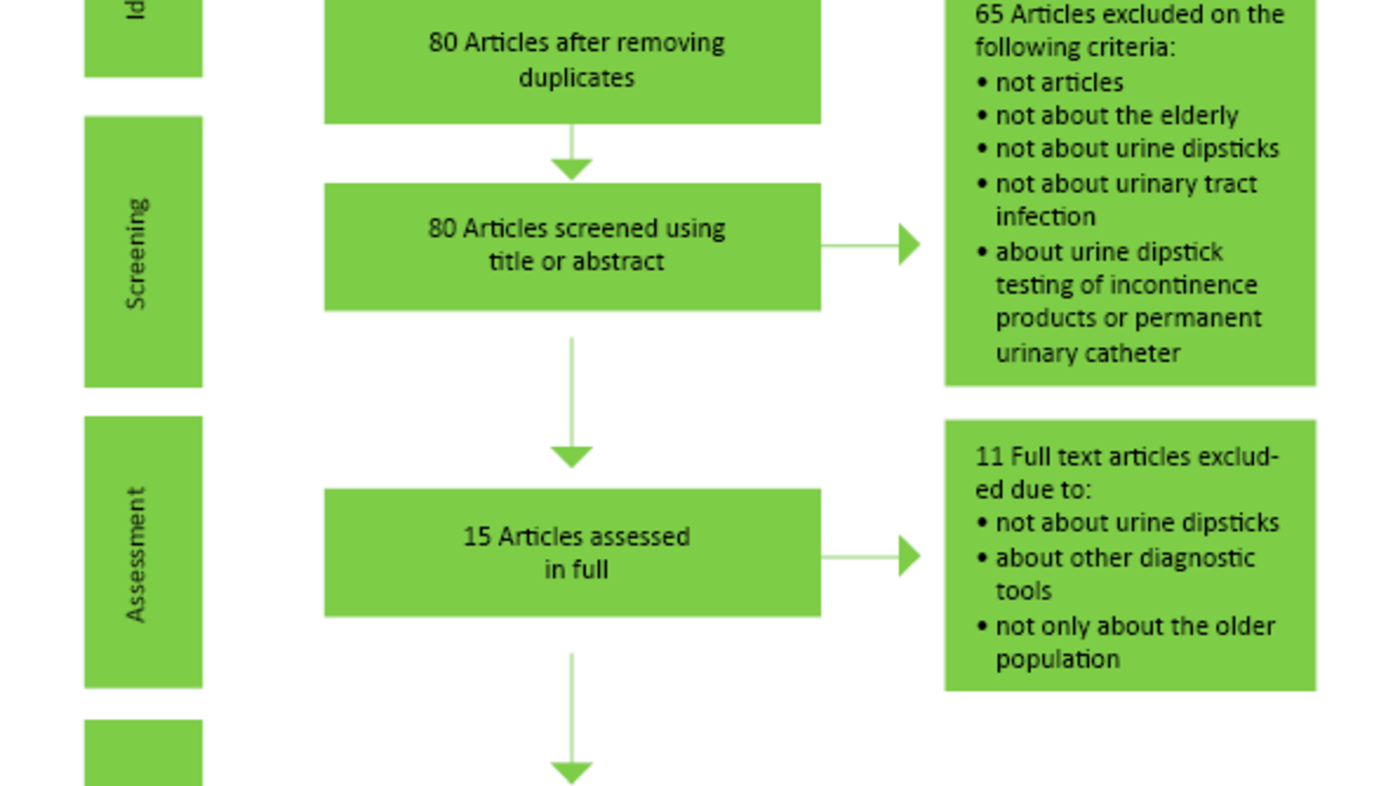

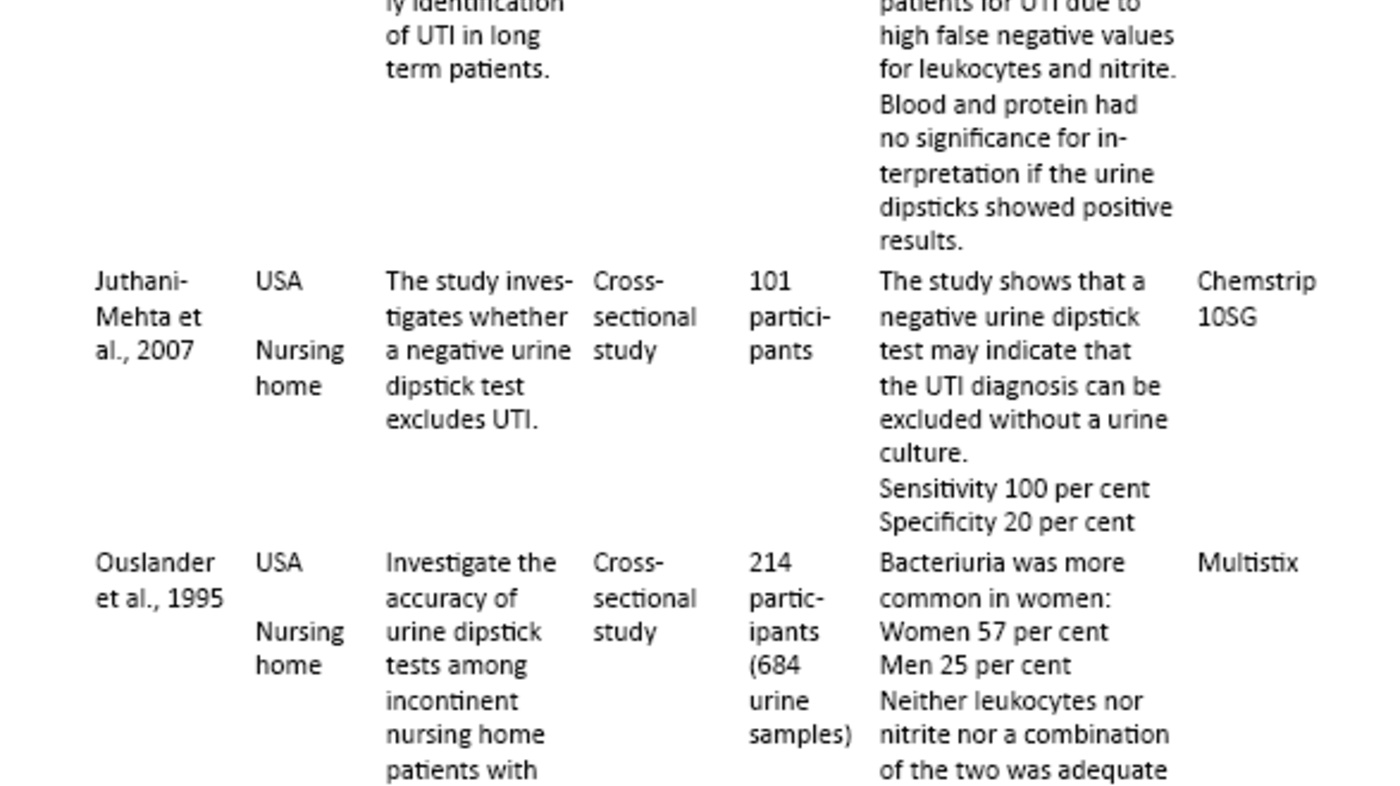

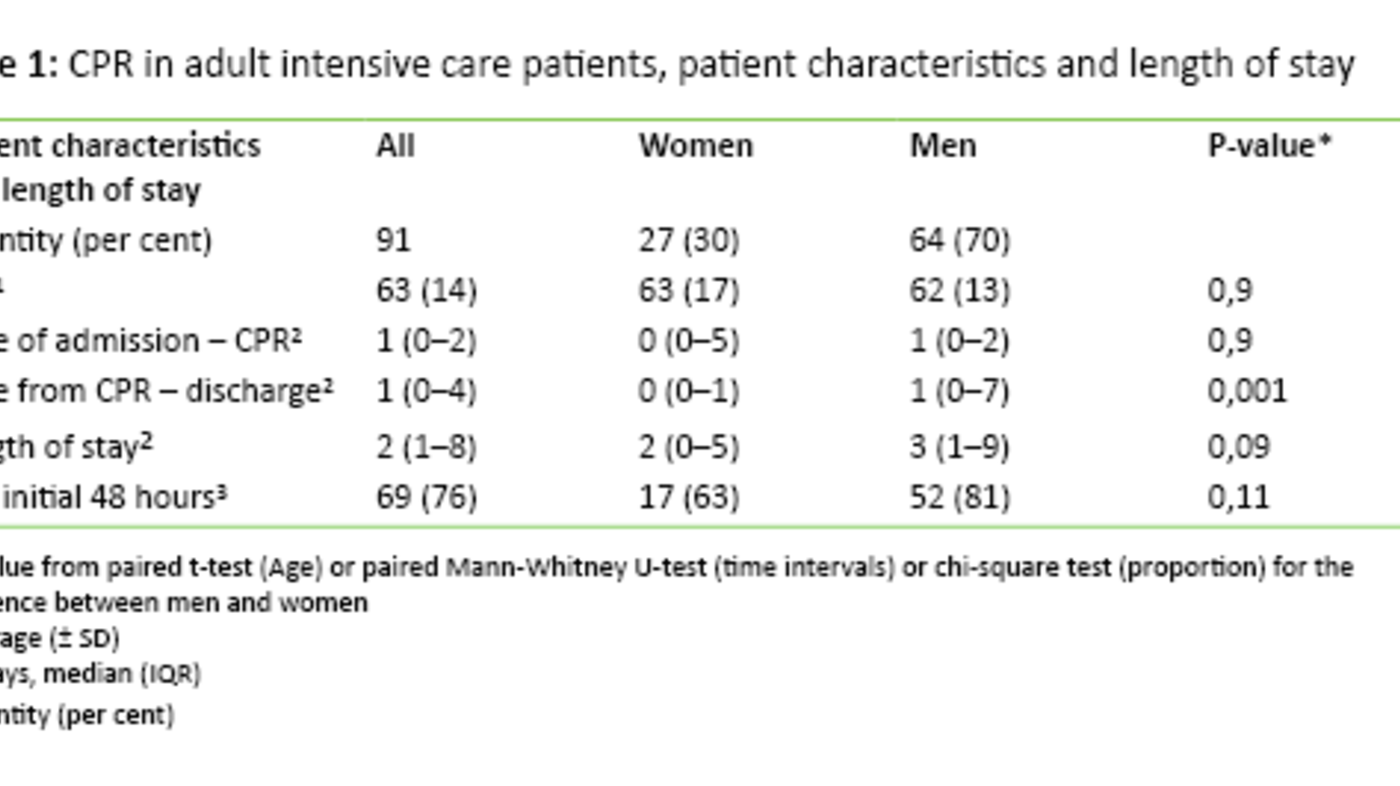

Of the 503 team members who were asked to complete the CPSET form, 293 (58 per cent) responded. This corresponds to 27 care processes for 17 different conditions, representing nine clinical areas (Table 1). Nineteen care processes/teams worked within somatics and eight were in mental health care. We excluded questionnaires that lacked answers to more than three of the 29 statements. For respondents who had answered 27 or more statements, we replaced the missing answers with the average of the scores for the remaining answers.

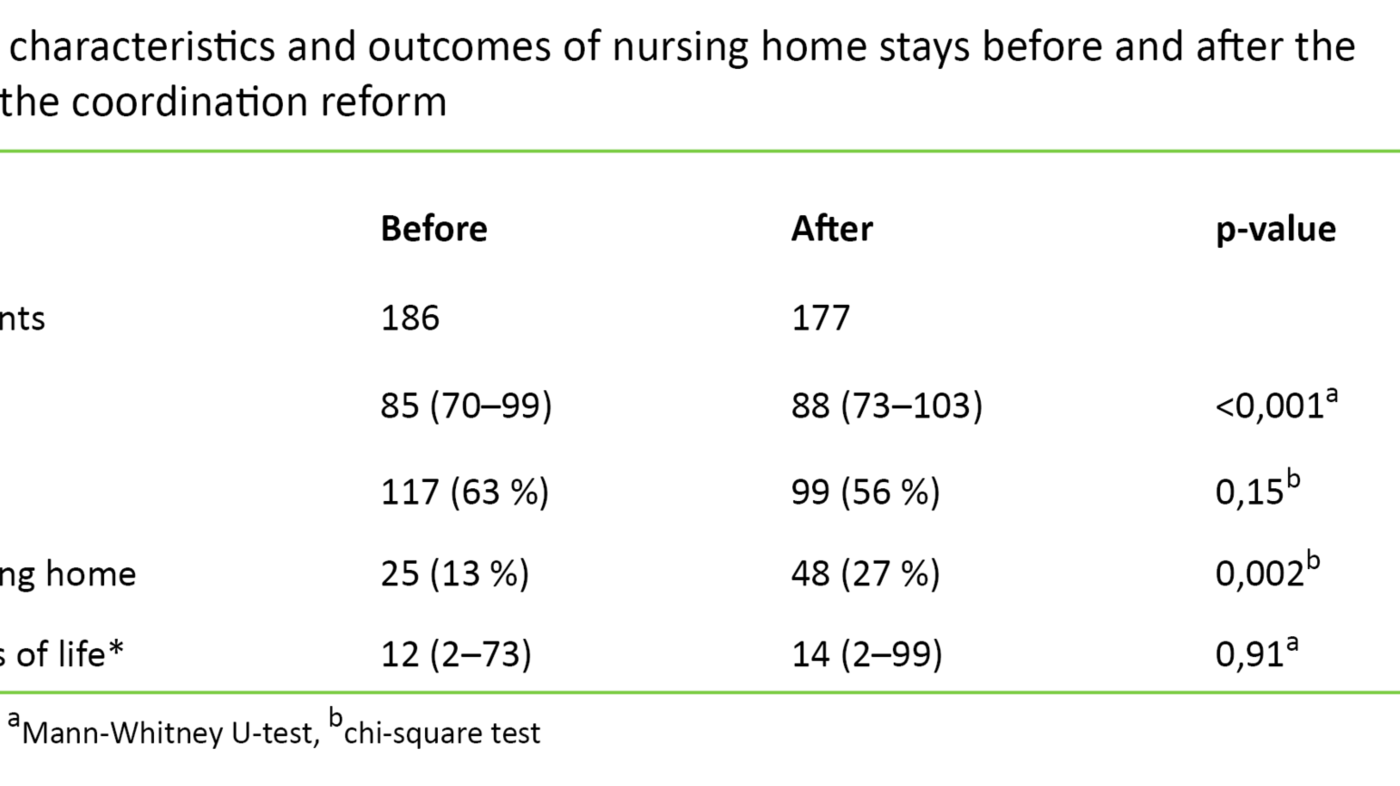

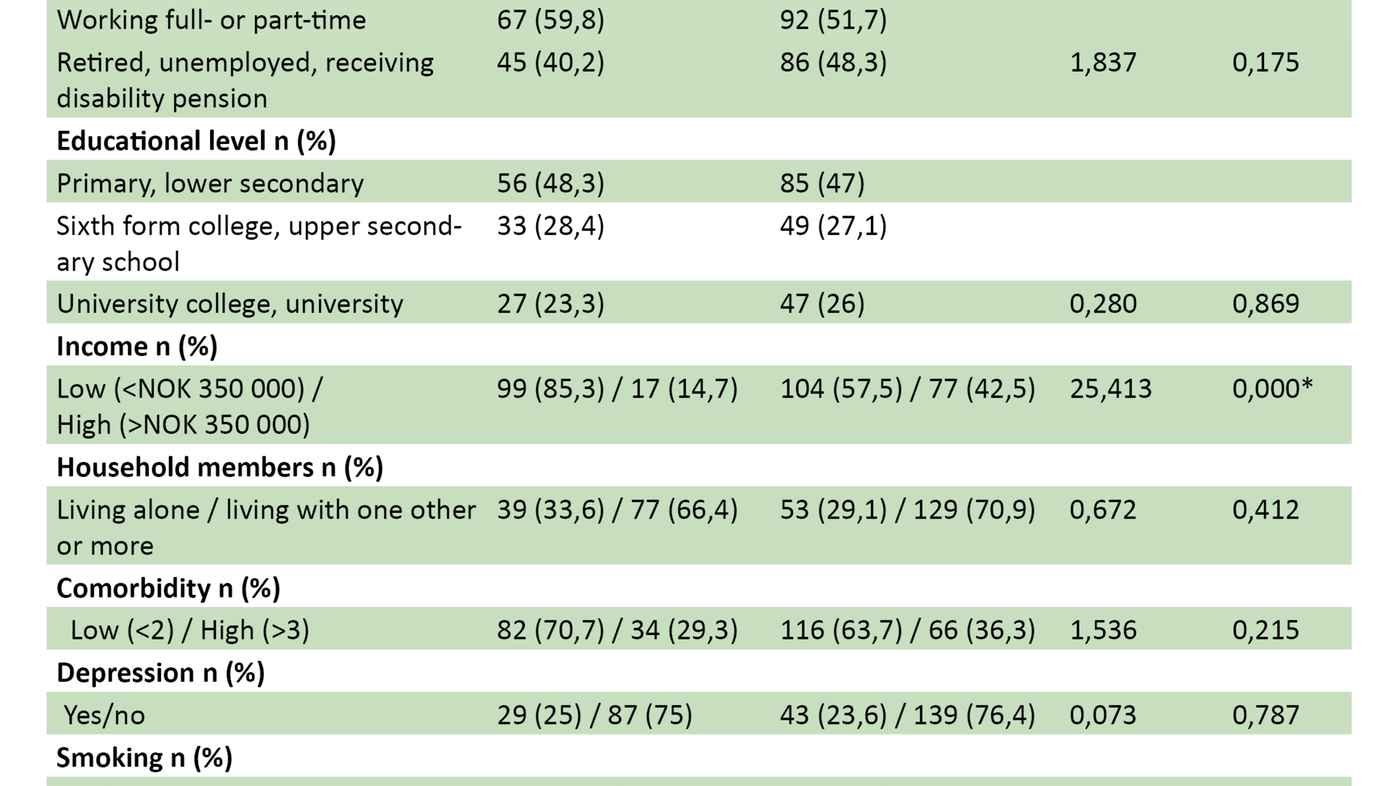

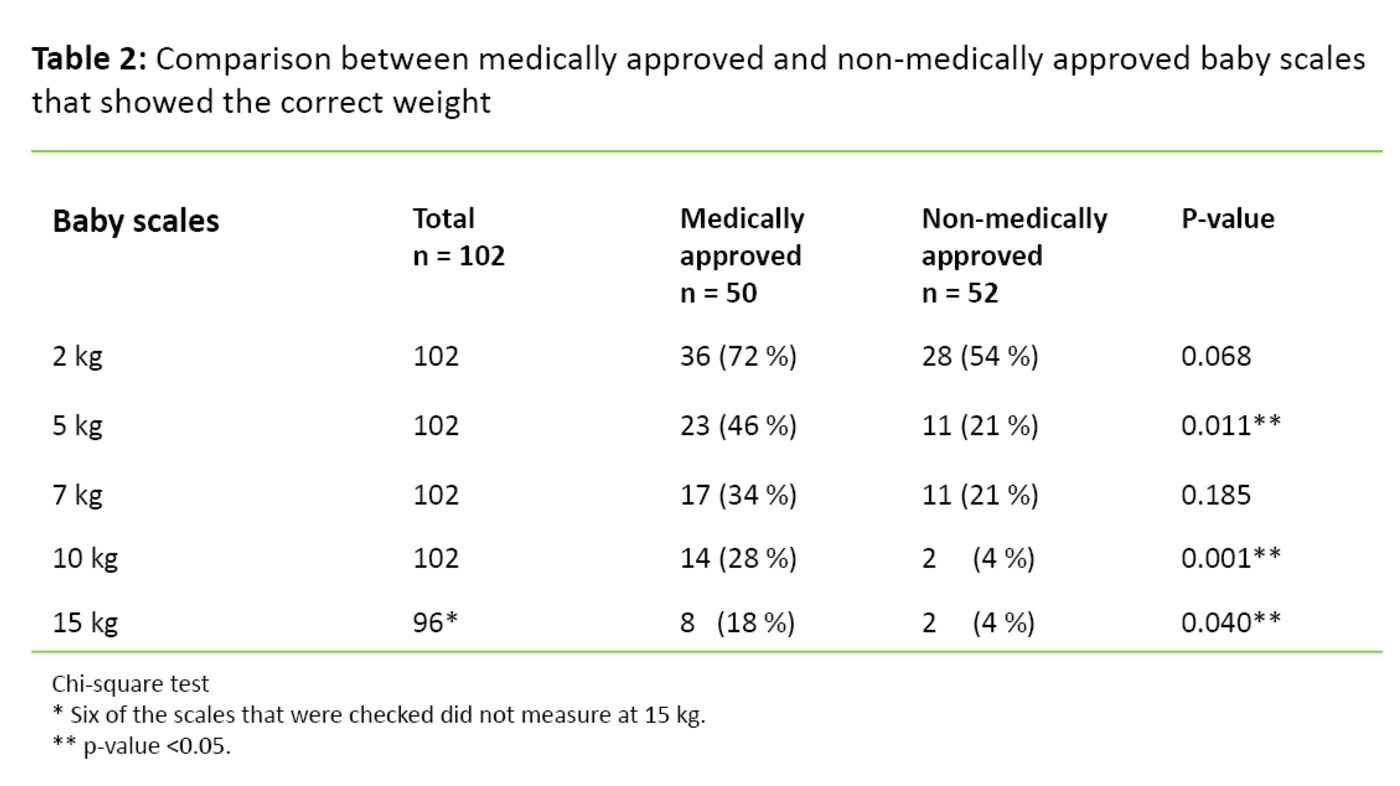

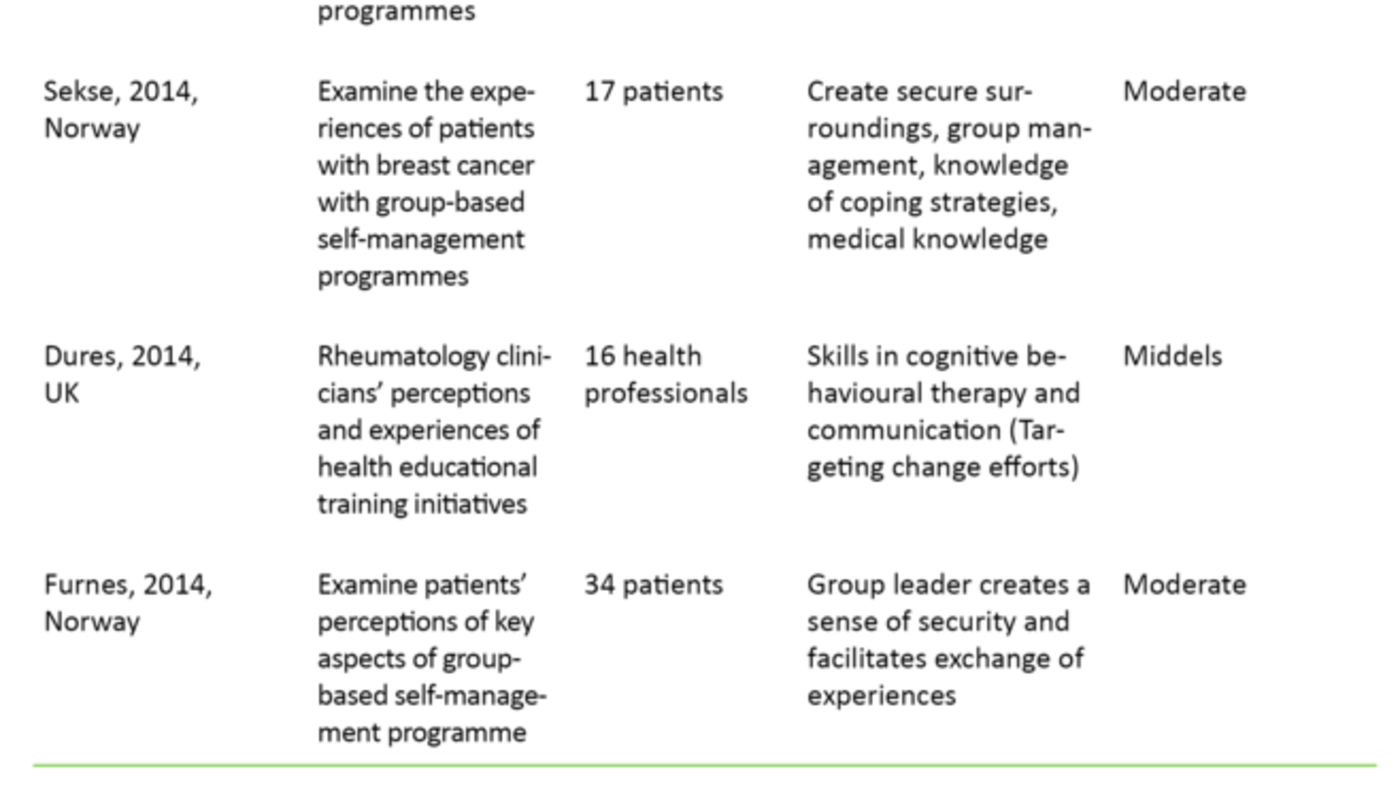

We excluded five care processes that had fewer than five respondents with valid answers and/or a response rate below 40 per cent. The final analysis file (N = 239) thus consisted of 22 care processes. Of these, 17 related to somatics and five to mental health care. The average valid response rate in the care processes included was 56 per cent. Descriptive statistics for background variables in the valid sample are shown in Table 2.

Health personnel’s perceptions of the organization in the selected care processes

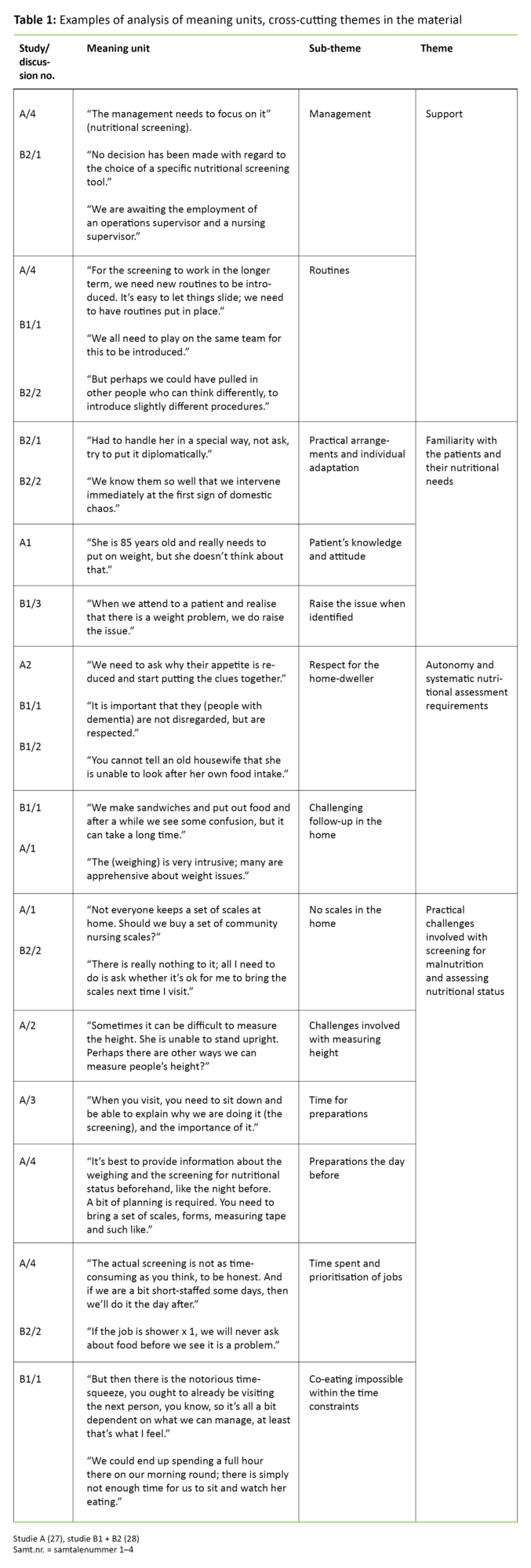

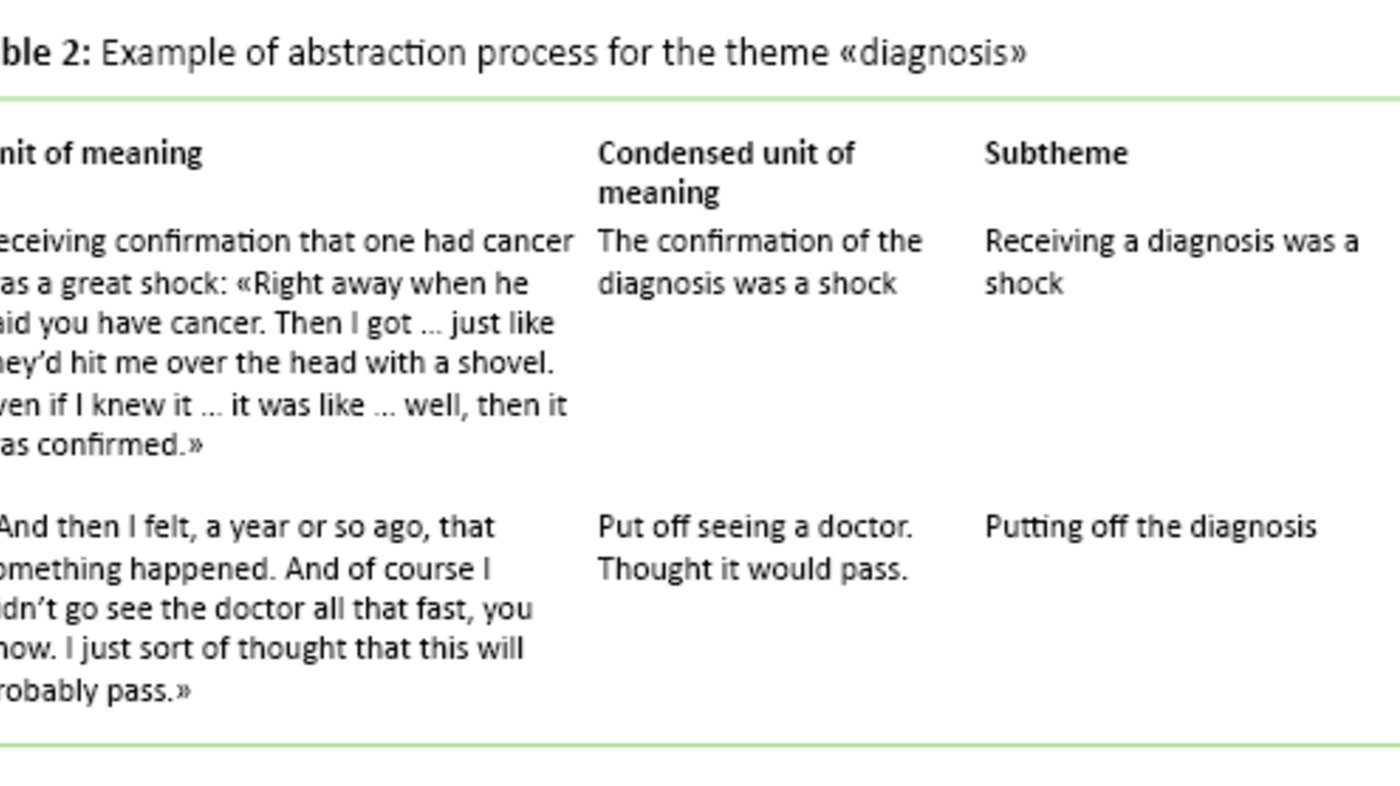

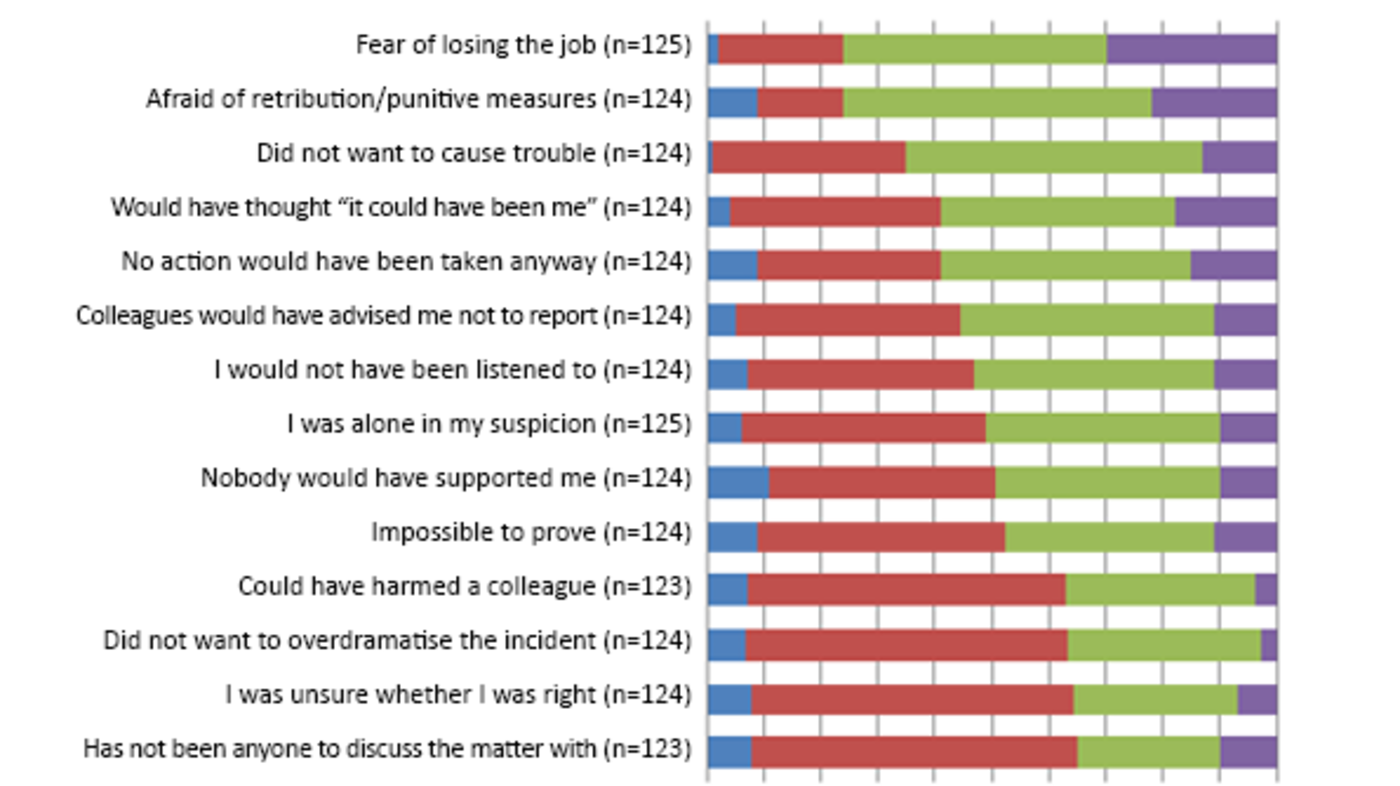

Figure 1 shows the average score with a 95 per cent CI for the 29 CPSET statements, in addition to the five sub-scales and the total scale in the valid sample (N = 239).

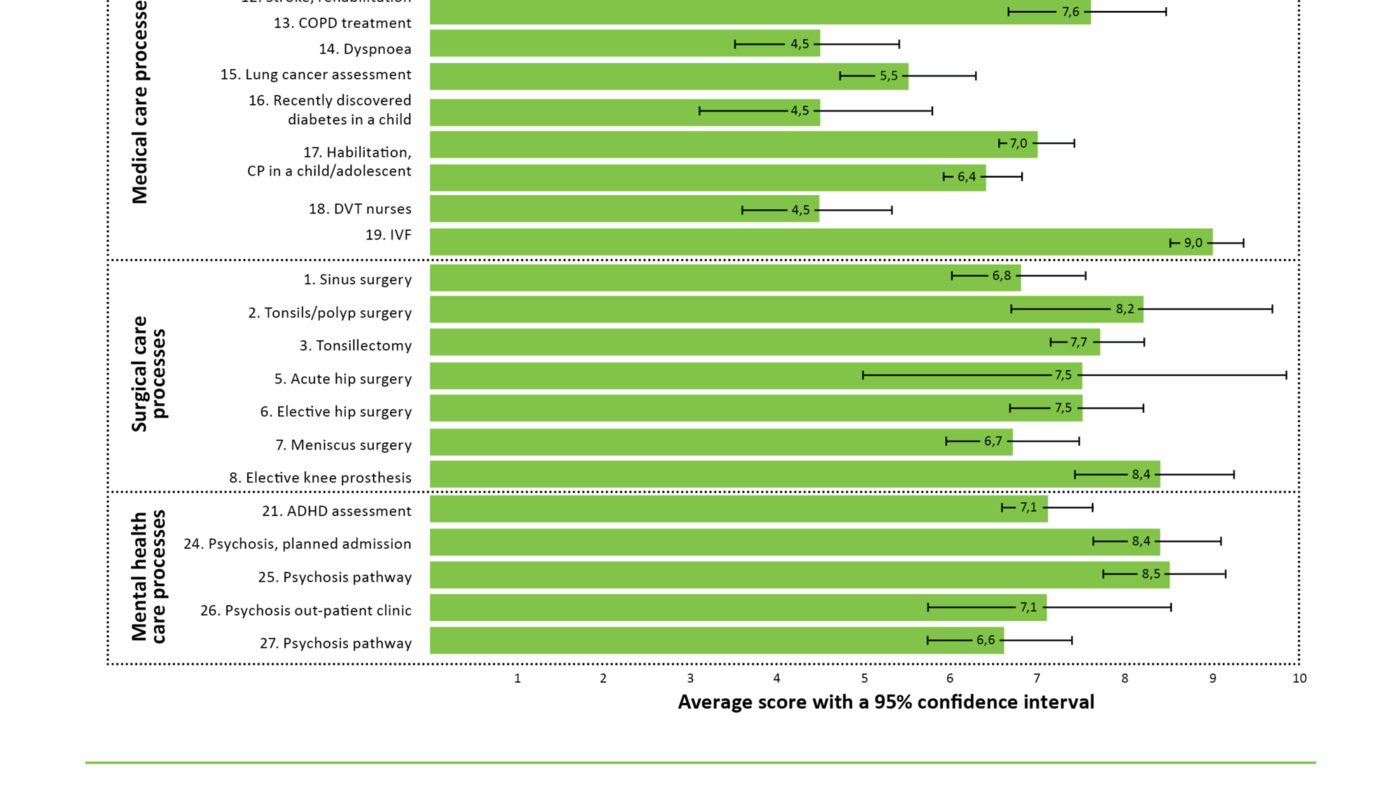

Figure 2 shows the average score with a 95 per cent CI for CPSET total scores per valid care process in the field of surgery, medicine and psychiatry. Of all the 22 care processes included, health care personnel in the care pathway ‘In vitro fertilization (IVF)’ gave the highest CPSET total score (9.0). Further examination of the average score with a 95 per cent CI in Figure 2 shows that health care personnel in the three lung-patient care processes gave a significantly poorer total score on the CPSET than most other care processes.

Staff in the care processes for stroke patients gave a significantly higher CPSET total score than those in the other processes. In the field of surgery, none of the processes stood out with a particularly high or low score. In mental health care, two care processes for patients with psychosis had significantly higher CPSET total scores than two of the other pathways in mental health care.

CPSET scores per organizational area

Examination of the 95 per cent CI limits on the five CPSET sub-scales (Figure 1) shows that the staff gave significantly higher scores on the sub-scales ‘Patient-focused organisation’ (PO) and ‘Coordination of the care process’ (COR) than on ‘Collaboration with primary care’ (SE) and ‘Monitoring and follow-up of the care process’ (OP).

Improved organization with written clinical procedures?

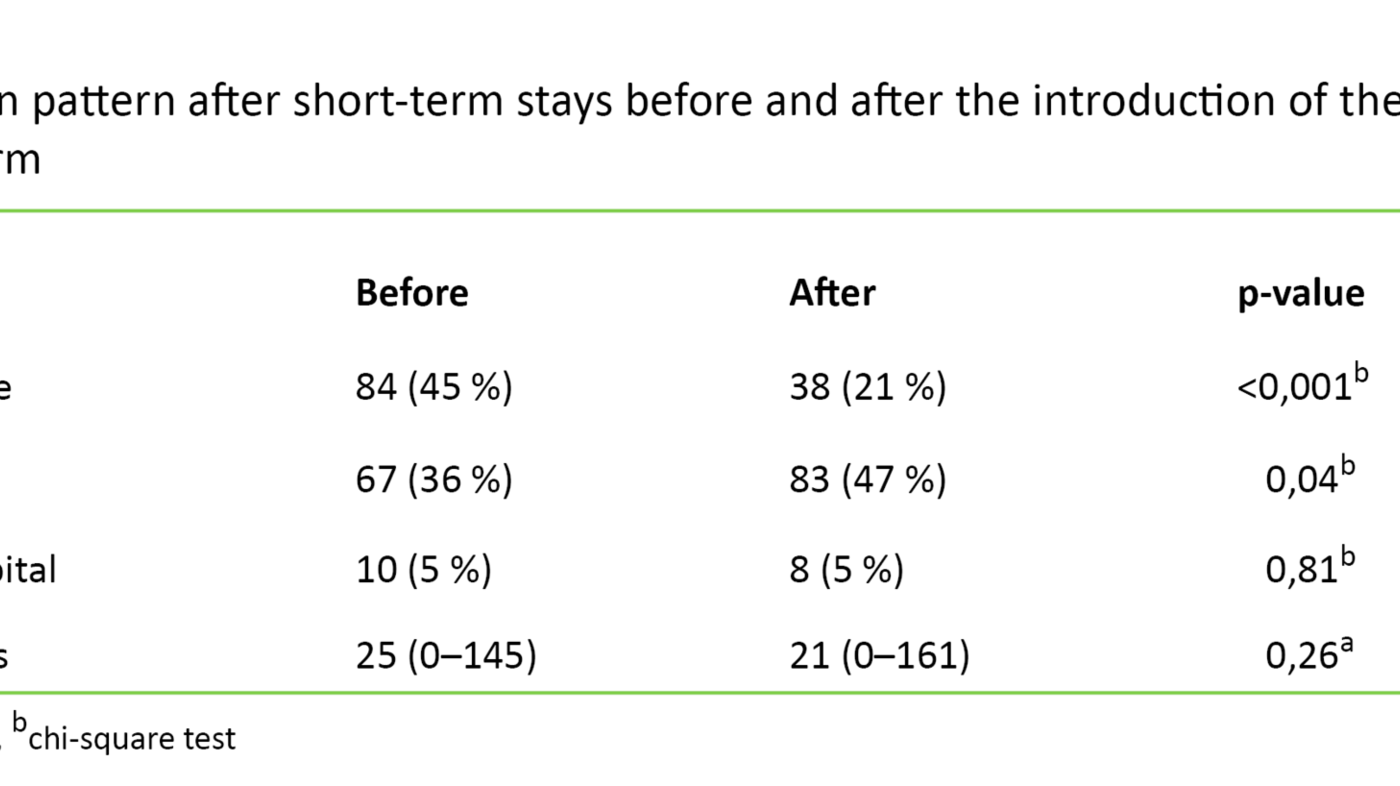

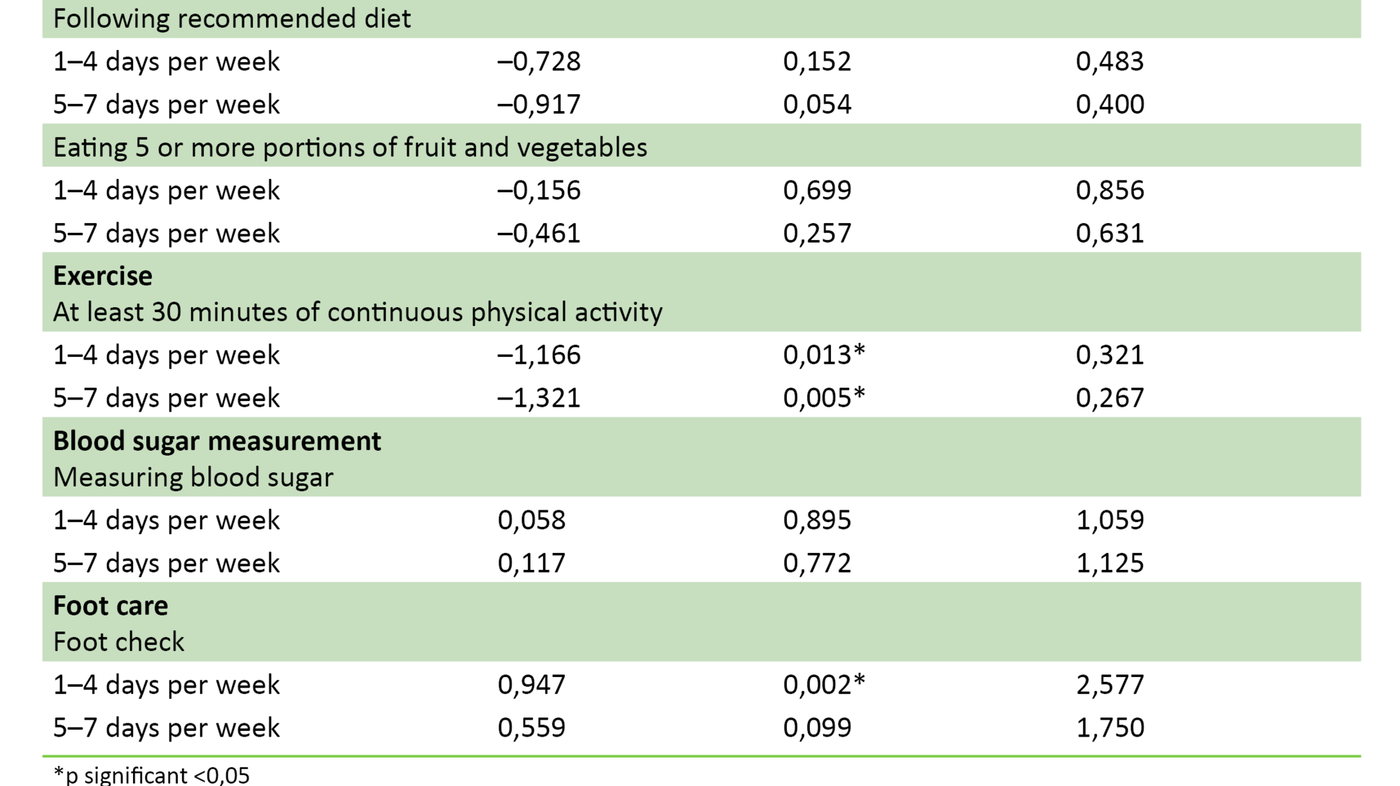

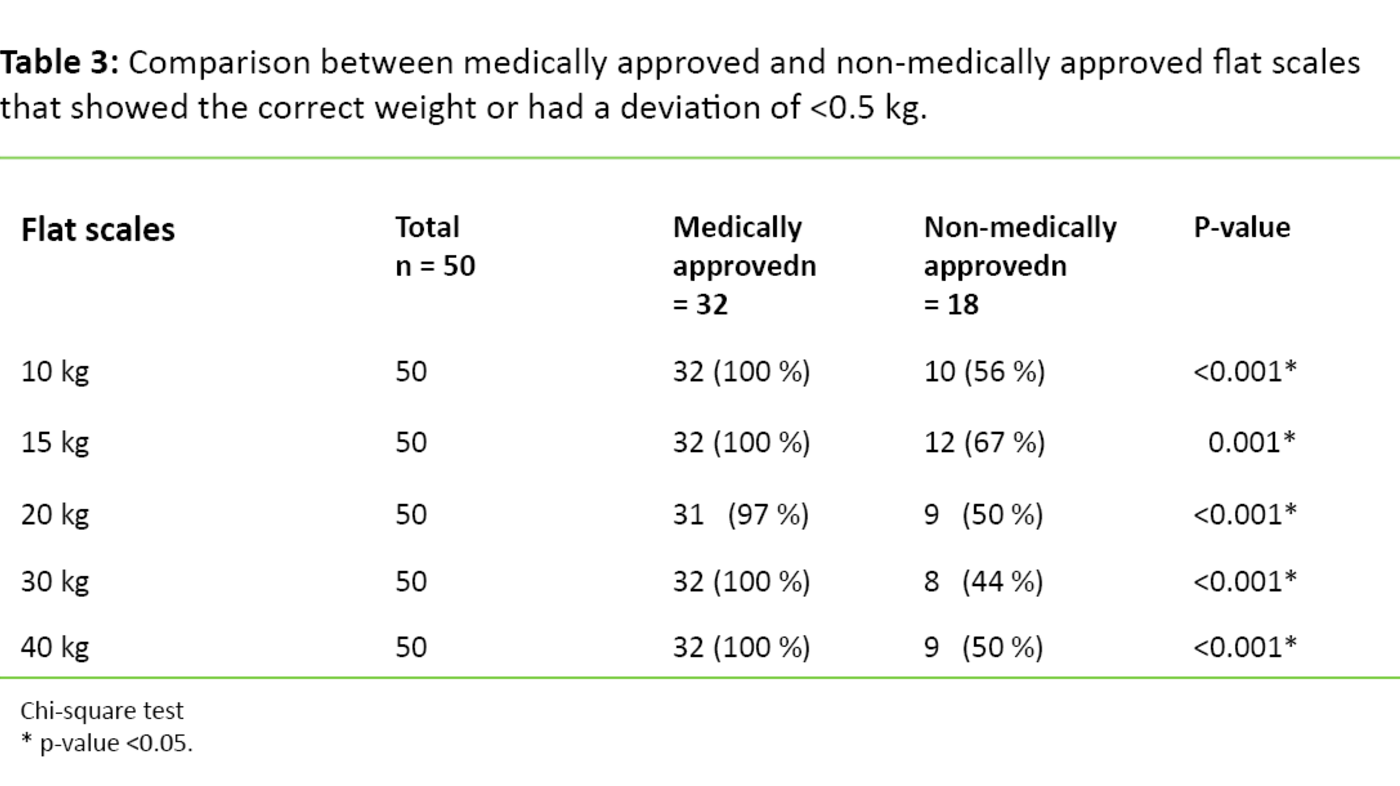

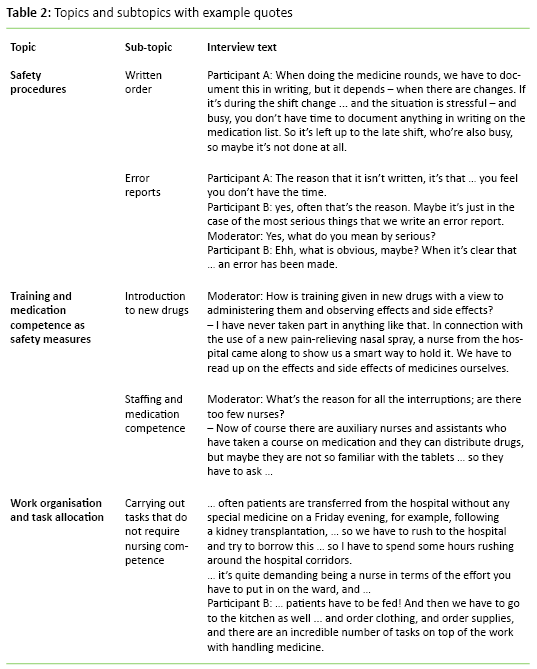

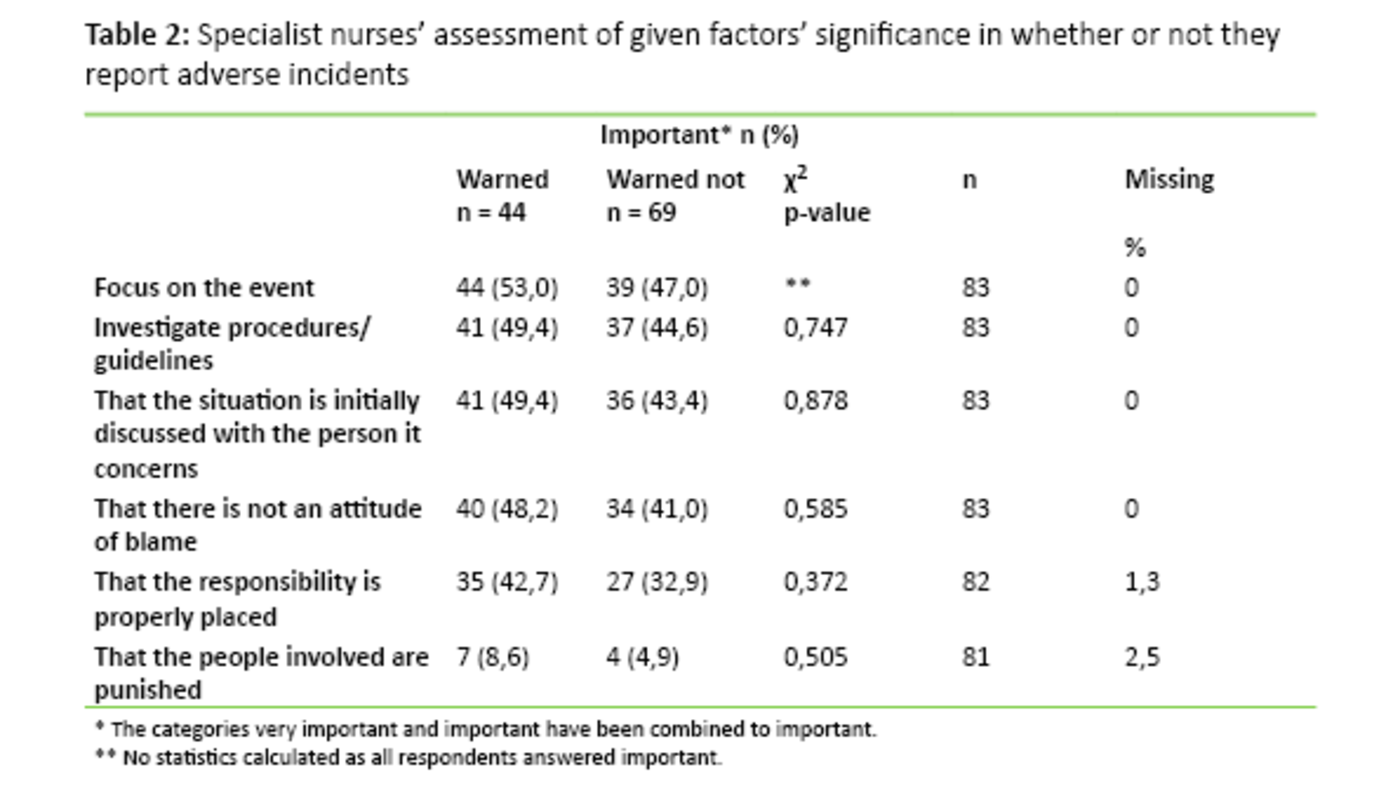

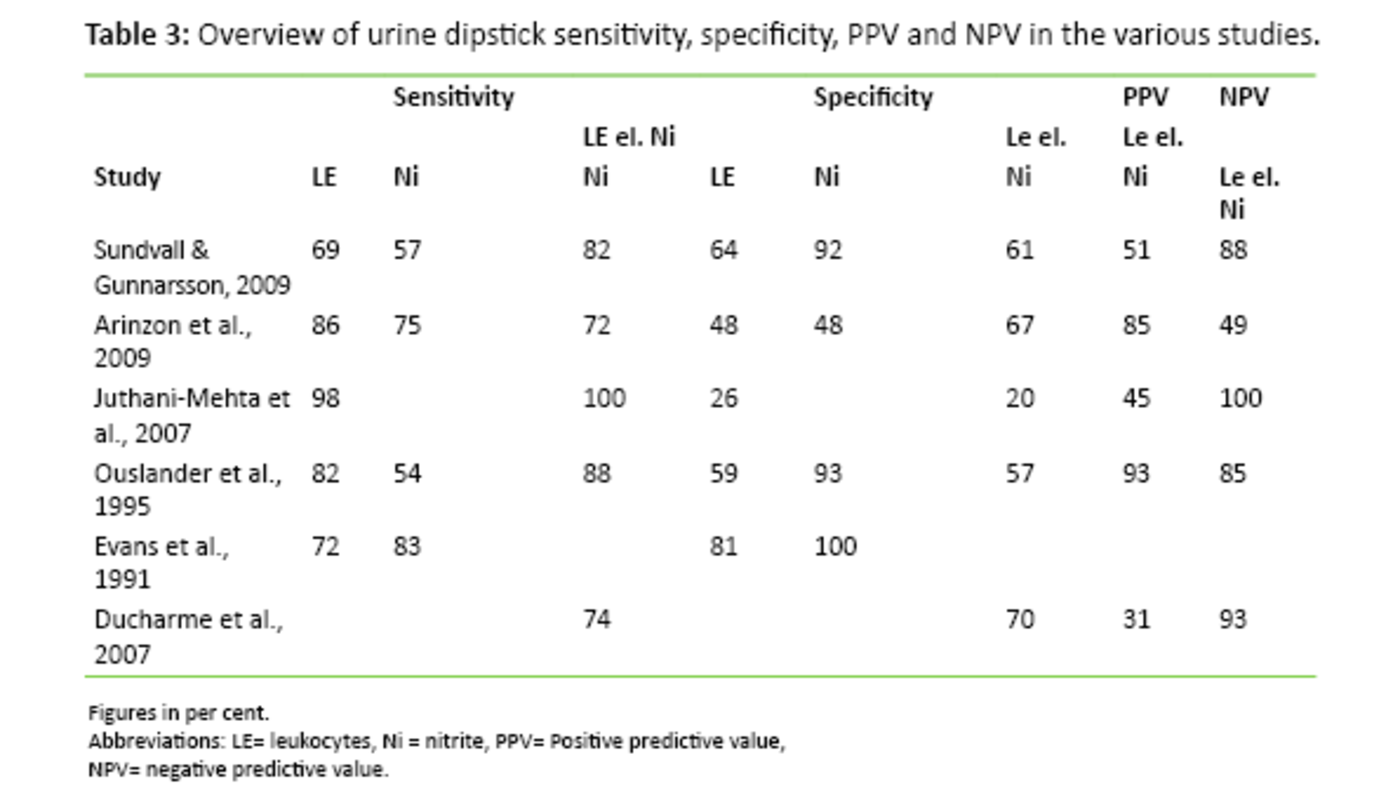

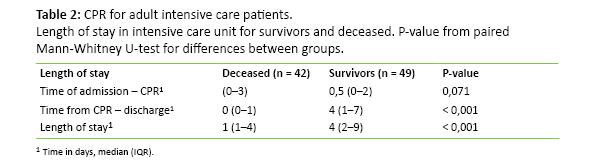

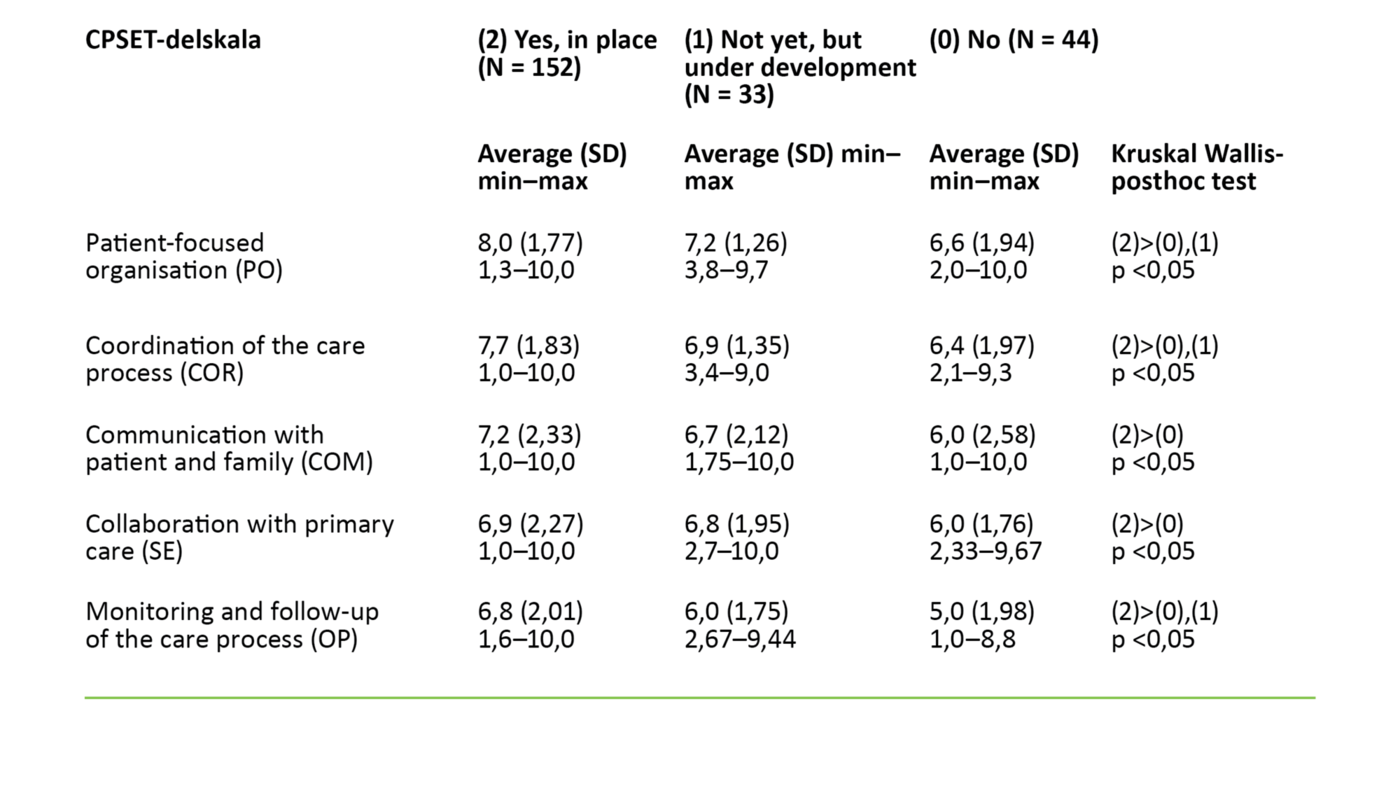

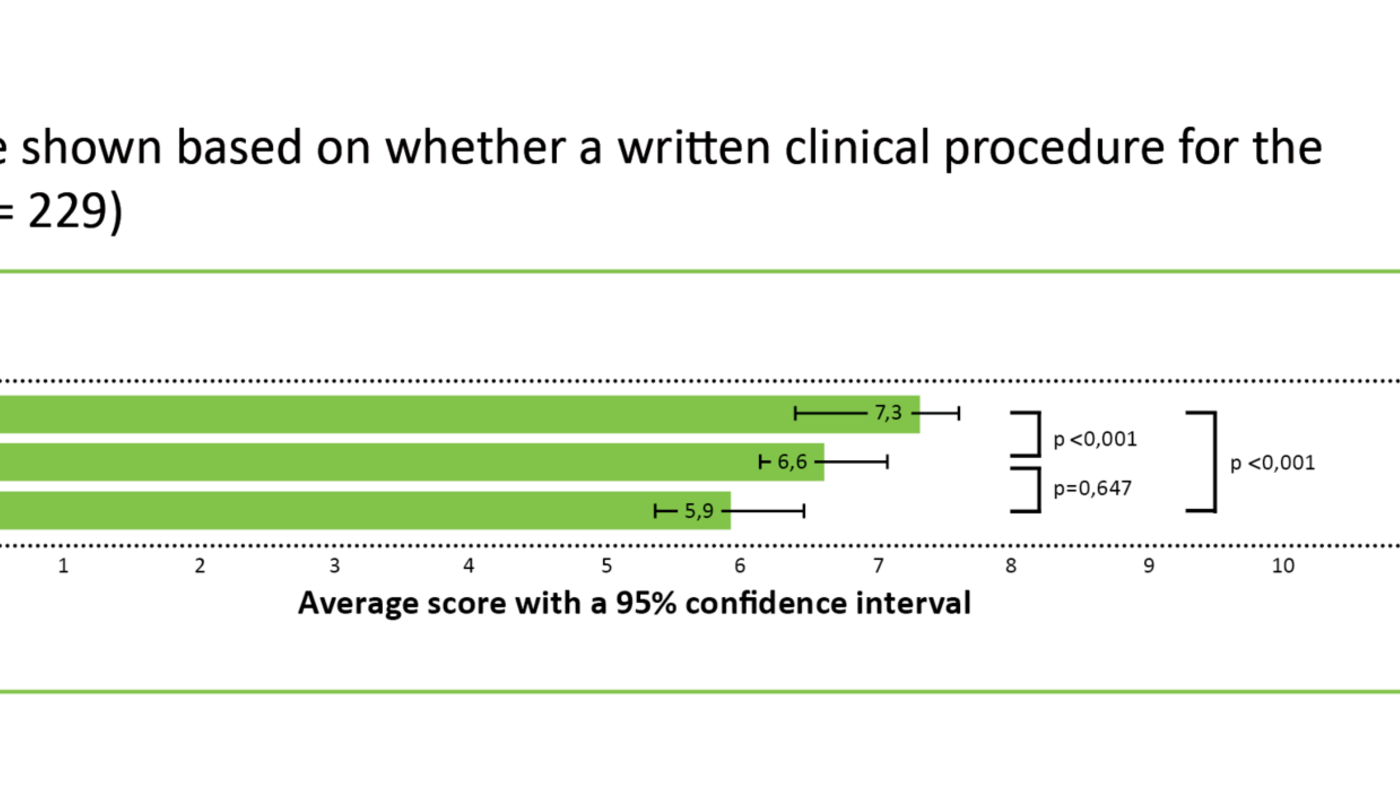

Table 2 shows the number of employees in the valid care processes who reported having a written clinical procedure in daily use in the care process. The total scores and sub-scores in the CPSET for employees in a care processes with a written clinical procedure in daily use were significantly higher than in the other two groups without a written clinical procedure in daily use (Table 3).

Figure 3 shows that the CPSET sub-scores range from the lowest scores in the care processes with no written clinical procedure in daily use, to the highest scores in the care pathways with a written clinical procedure in daily use.

Discussion

We found that the health care personnel’s perceptions of the organization of care processes in Western Norway Regional Health Authority vary, but on average they reported the quality of the organization as one point higher on the CPSET total scale than that reported by Belgian and Dutch health care staff in 2013 (30). However, among the Norwegian health care workers, the sub-scales ‘Monitoring and follow-up of the care process’ and ‘Collaboration with primary care’ were below average in relation to the Belgian and Dutch figures (30).

This finding, and the fact that the study sample considered the sub-scales ‘Monitoring and follow-up of the care process’ and ‘Collaboration with primary care’ to be poorer than ‘Patient-focused organization’ and ‘Coordination of the care process’ indicates that there is a need to improve the systematic follow-up of care pathways and the collaboration between primary care and specialist care in Norway.

Clinical procedures are associated with higher scores

Many studies have shown that standardizing care processes has a positive effect on teamwork and process outcomes in the health service (11, 16-21). In line with Vanhaecht et al. (2009) (17), we found that health care personnel considered the organization of care pathways with a written clinical procedure to be better than care processes that did not have such a procedure. In our study, care pathways with a written clinical procedure had the highest average CPSET scores. The staff in the highest scoring care pathways had been working systematically to improve the quality of treatment and follow-up of patients in recent years. The care processes with the lowest scores had either not adopted a written clinical procedure or the respondents were unsure whether such written procedures existed.

Quality, efficiency and the safeguarding of comprehensive and coordinated care pathways are key elements of the regional health authorities’ mandate and of the new national research strategy Health&Care21 (33). A wide range of initiatives have been implemented over the last 20 years aimed at improving the quality of health services in Norway. These initiatives include various ‘Breakthrough’ projects such as the Norwegian Patient Safety Programme: In Safe Hands using Global Trigger Tool (34), and the introduction of checklists (35).

This strong focus on quality and coordination in the Norwegian health service in recent years may be an alternative explanation as to why health care personnel in some care processes give the care process a lower score. Perhaps those who work with these care processes gave lower scores precisely because they set the bar high for themselves and their units when it comes to the organization of the care process.

Varying perceptions of the ‘care pathway’ concept

During the pilot study of CPSET, it emerged that professionals in the specialist health service interpreted the concepts of ‘care process’ and ‘care pathway’ in quite a few different ways. A written document describing necessary treatment measures in a sequential order is essential in most methods for standardizing care processes. However, we do not know of any Norwegian term for a comprehensive written document that corresponds to the English term ‘pathway document’ (10).

In order to make it easier for the respondents to understand what we were looking for, we therefore used the term ‘written clinical procedure in the care process’ in the questionnaire. We do not know whether respondents considered this term to be ambiguous, and using ‘written clinical procedure in the care process’ instead of ‘standardized care process’ or ‘care pathway’ may have made the findings less valid.

Some care processes, where health care personnel and managers had a strong focus on quality improvement, may have been more frequently included than other care processes, since the managers were asked to select care processes. However, the opposite is also conceivable, where managers who saw the need for improving the coordination of the treatment of patient groups in a unit wanted the staff who were responsible for this patient group to answer the CPSET statements.

One other potential source of error is that the parties involved may have had different understandings of the ‘care process’ concept, and if the term was less relevant, it may have made the findings less accurate. On the other hand, it could be argued that the results have a strong ecological validity because the units themselves defined ‘care process’ based on how this term was understood by staff in the Norwegian specialist health service today.

Not all disciplines were included

We believe that because so many different disciplines, occupation groups and units were represented, the findings can be generalized to a greater extent than if only a few occupations, disciplines and care processes had been included. However, some important occupation groups did not respond to the CPSET. For example, radiologists and radiographers, who are key personnel in the processes for stroke patients, were not represented, and doctors were also generally underrepresented. Doctors often initiate treatment measures, and may therefore perceive the organization as better than other occupation groups.

In the deep vein thrombosis (DVT) care pathway, only nurses were asked to participate, despite the fact that the CPSET was developed to measure the organization in an interdisciplinary team perspective. In general, nurses have close contact with the patient, and they can play a central role in the coordination between different occupation groups and units, but in this care pathway as well as others, overrepresentation or underrepresentation of occupation groups can lead to a somewhat skewed result.

We have recently shown that the Norwegian version of the CPSET has acceptable psychometric attributes (convergent validity, reliability) (32). Other translated instruments that measure coordination and communication are the Relational Coordination Survey (RCS) (36, 37) and the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire (38).

An important snapshot

Despite the weaknesses of the study mentioned above, we believe that our results provide an important snapshot of care processes in the Norwegian context. Although care processes have been mapped and researched in Norway (23–27, 39–45), we do not know of any other large-scale studies that have used validated measuring instruments and extensive sampling from a wide range of units in the Norwegian health service. We therefore believe that the knowledge this study provides about the organization of care processes is useful for health care personnel and managers who have a strong focus on quality improvement and patient safety.

Future research should link systematic quality work aimed at improving work processes to relevant outcome goals at the system and patient level. These may be related to complications, recovery and resource use. It will be particularly important to include the user perspective in future studies. This will throw light on whether and how the standardization of care processes impacts on the service user’s experiences of how they are approached and treated and whether they think they are given the opportunity to make important decisions about their own treatment and health care within the framework of standardization (46).

Conclusion

The average CPSET total score was higher than the equivalent international measurements. Staff in the specialist health service who were associated with care pathways that had a written clinical procedure reported better coordination of the treatment process than personnel in care processes where there was no such procedure.

The specialist health service should improve the systematic and targeted quality work by standardizing and following up care processes, and the collaboration with primary care should be strengthened. In this work, we believe it is particularly important to protect the user’s perspective, both in relation to treatment experiences and outcomes.

I would like to extend thanks to all staff in Western Norway Regional Health Authority who participated in the survey. Thanks also to Sissel Hauge at Stord Hospital for her linguistic assistance. The project was funded by the liaison committee in Western Norway Regional Health Authority through the Research Network on Integrated Health Care in Western Norway at Fonna Hospital Trust.

References

1. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Nasjonal helse- og sykehusplan (2016–2019). Oslo. 2015.

2. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Meld. St. 11 (2014–2015) Kvalitet og pasientsikkerhet 2013. Oslo. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet.

3. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Meld. St. 10 (2012–2013) God kvalitet – trygge tjenester – Kvalitet og pasientsikkerhet i helse- og omsorgstjenesten. Oslo. 2012.

4. Helse-og omsorgsdepartementet. Sammen – mot kreft. Nasjonal kreftstrategi 2013–2017. Oslo. 2013.

5. Vanhaecht K, Bollmann M, Bower K, Gallagher C, Gardini A, Guezo J, et al. Prevalence and use of clinical pathways in 23 countries – an international survey by the European Pathway Association. J Integr Care Pathways. 2006;10:28.

6. De Bleser L, Depreitere R, De Waele K, Vanhaecht K, Vlayen J, Sermeus W. Defining pathways. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14:553–63.

7. Panella M, Vanhaecht K. Is there still need for confusion about pathways? Int J Care Pathw. 2010;14:1–3.

8. Eggen R. Veileder, retningslinje, behandlingslinje, pasientforløp – hva er forskjellen? Available at: http://www.helsebiblioteket.no/psykisk-helse/aktuelt/veileder-retningslinje-behandlingslinje-pasientforlop-hva-er-forskjellen (downloaded 20.02.16).

9. Vanhaecht K. Care Pathways are defined as complex interventions. BMC Medicine. 2010;8(31).

10. Vanhaecht K, Van Gerven E, Deneckere S, Lodewijckx C, Janssen I, van Zelm R et al. The 7-phase method to design, implement and evaluate care pathways. International Journal of Person Centered Medicine. 2012;2:341–51.

11. Biringer E, Klausen OG, Lærum BN, Hartveit M, Vanhaecht K. Betre kvalitet med behandlingsliner. Sykepleien. 2013:62–4. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2013/02/betre-kvalitet-med-behandlingsliner(downloaded 19.05.2017).

12. Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Sermeus W. The impact of clinical pathways on the organisation of care processes. Leuven: ACCO. 2007.

13. Nelson E, Godfrey M, Batalden P, Berry S, Bothe A, McKinley K, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 1. The building blocks of health systems. J Comm J Qual Pat Safety. 2008;34:367–78.

14. Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W. The Leuven Clinical Pathway Compass. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways. 2003;7:2-7.

15. Vanhaecht K, Van Zelm R, Van Gerven E, Sermeus W, Bower K, Panella M et al. The 3-blackboard method as consensus-development exercise for building care pathways. Int J Care Pathways. 2010;15(3):49–52.

16. Van Herck P, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W. Effects of clinical pathways: do they work? J Integr Care Pathways. 2004;8:95–104.

17. Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Panella M, Sermeus W. Do pathways lead to better organized care processes? J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(5):782–8.

18. Reinar L. Behandlingslinjer reduserer komplikasjoner for pasienter i sykehus. Sykepleien. 2010:91-2. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2010/06/behandlingslinjer-reduserer-komplikasjoner-pasienter-i-sykehus(downloaded 19.05.2017).

19. Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, Machotta A, Gothe H, Willis J et al. Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs (Review). The Cochrane Library. 2010.

20. Deneckere S, Euwema M, Lodewijckx C, Panella M, Mutsvari T, Sermeus W, et al. Better interprofessional teamwork, higher level of organized care, and lower risk of burnout in acute health care teams using care pathways: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Med Care. 2013;51:99–107.

21. Deneckere S, Euwema M, Van Herck P, Lodewijckx C, Panella M, Sermeus W et al. Care pathways lead to better teamwork: Results of a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:264–8.

22. Allen D, Gillen E, Rixson L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of integrated care pathways: what works, for whom, in which circumstances? Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2009;7:61–4.

23. Iversen G, Haugen D. Liverpool Care Pathway: Personalets erfaringer i to norske sykehus. Sykepleien. 2015;10:144–51. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2015/05/personalets-erfaringer-i-norske-sykehus(downloaded 19.05.2017).

24. Aasebo U, Strom HH, Postmyr M. The Lean method as a clinical pathway facilitator in patients with lung cancer. Clin Resp J. 2012;6:169–74.

25. Hovlid E, Bukve O, Haug K, Aslaksen AB, von Plessen C. A new pathway for elective surgery to reduce cancellation rates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:154.

26. Saltvedt I, Prestmo A, Einarsen E, Johnsen LG, Helbostad JL, Sletvold O. Development and delivery of patient treatment in the Trondheim Hip Fracture Trial. A new geriatric in-hospital pathway for elderly patients with hip fracture. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:355.

27. Prestmo A, Hagen G, Sletvold O, Helbostad JL, Thingstad P, Taraldsen K et al. Comprehensive geriatric care for patients with hip fractures: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1623–33.

28. Care Process Self-Evaluation Tool (CSPET). Available at: https://helse-fonna.no/seksjon-avdeling/Documents/Forsking%20og%20innovasjon/Verktøy%20og%20instrument/CPSET-norsk.pdf(downloaded 19.05.2017).

29. Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Depreitere R, Van Zelm R, De Bleser L, Proost K et al. Development and validation of a care process self-evaluation tool. Health Serv Manag Res. 2007;20:189.

30. Seys D, Deneckere S, Sermeus W, Van Gerven E, Panella M, Bruyneel L, et al. The Care Process Self-Evaluation Tool: a valid and reliable instrument for measuring care process organization of health care teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:325.

31. Camacho-Bejarano R, Mariscal-Crespo M, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K, Merino-Navarro D. Validation of the Spanish version of the care process self-evaluation tool. Int J Care Pathways. 2012;16:35.

32. Størkson S, Biringer E, Hartveit M, Aßmus J, Vanhaecht K. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Care Process Self-Evaluation Tool (CPSET). J Interprof Care 2016; 30:804-11.

33. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. HelseOmsorg21. Et kunnskapssystem for bedre folkehelse Nasjonal forsknings- og innovasjonsstrategi for helse og omsorg. Oslo. 2014.

34. Deilkås E. Sluttrapport for pasientsikkerhetskampanjen «I trygge hender 24–7» (2011–2013). Oslo. Kunnskapssenteret. 2014.

35. Thomassen O, Espeland A, Softeland E, Lossius HM, Heltne JK, Brattebo G. Implementation of checklists in health care; learning from high-reliability organisations. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:53.

36. Gittell JH, Fairfield KM, Bierbaum B, Head W, Jackson R, Kelly M et al. Impact of Relational Coordination on Quality of Care, Postoperative Pain and Functioning, and Length of Stay: A Nine-Hospital Study of Surgical Patients. Med Care. 2000;38:807–19.

37. Gittell JH, Godfrey M, Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional collaborative practice and relational coordination: Improving healthcare through relationships. J Interprof Care. 2013;27:210–3.

38. Uijen A, Schers H, Schellevis F, Mokkink H, van Weel C, van den Bosch W. Measuring continuity of care: psychometric properties of the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire. Br J Gen Practice. 2012;62:e949–57.

39. Johannessen AK, Luras H, Steihaug S. The role of an intermediate unit in a clinical pathway. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e012.

40. Hermansen O, Salthaug E. Prosessledelse og standardiserte pasientforløp En kvalitativ casestudie av to norske sykehus. (Master's thesis). Bergen. Norges handelshøyskole. 2014.

41. Neverdal M, Rystad K. Å samhandle om samhandling Etablering av et standardisert pasientforløp på tvers av spesialist- og kommunehelsetjenesten. (Master's thesis). Trondheim. NTNU. 2014.

42. Hermansen O, Salthaug E. Care pathways and business process management (BPM). E-P-A Newsletter. 2015;(18):1–2.

43. Rosstad T, Garasen H, Steinsbekk A, Haland E, Kristoffersen L, Grimsmo A. Implementing a care pathway for elderly patients, a comparative qualitative process evaluation in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:86.

44. Desserud KF, Veen T, Soreide K. Emergency general surgery in the geriatric patient. Br J Surg. 2016 Jan;103(2):e52–61.

45. Haland E, Rosstad T, Osmundsen TC. Care pathways as boundary objects between primary and secondary care: Experiences from Norwegian home care services. Health. 2015;19:635–51.

46. Biringer E, Hartveit M. Ja til ei betre teneste. Dagens medisin. Kronikk og debatt. 21/2015.

Norwegian health care personnel find the systematic follow-up of care pathways and the collaboration with the primary health service to be poorer than other organizational areas.

Background: The organization of health care in Norway poses a number of challenges in terms of assessment, treatment and follow-up. The introduction of care pathways in oncology has increased the focus on systematic improvement of care processes as a means of quality improvement. However, it is unclear how well the existing care processes are currently organized.

Objective: To assess health care personnel’s perceptions of the organization of care processes in the specialist health service in Norway.

Method: The Care Process Self-Evaluation Tool (CPSET) assesses five dimensions of the organization of care processes: Patient-focused organization, Coordination of the care process, Communication with patients and family, Collaboration with primary care, and Monitoring and follow-up of the care process. Employees (N = 503) in 27 selected care processes in the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Vest) were asked to complete the CPSET. Analyses were based on responses from 239 employees in 22 valid care processes (48 per cent response rate).

Results: The CPSET average score of 6.9 (standard deviation 1.80) in the sample was higher than comparable international figures. However, Norwegian employees considered the follow-up of the care process and the collaboration with primary care to be poorer than other dimensions of care organization. Care processes with a written clinical procedure were better organized than processes without such standardization.

Conclusion: The specialist health service should improve the systematic follow-up of care pathways as well as the collaboration with primary care.