Burden, coping and mental health among the next of kin of people with a substance abuse problem

It can be an enormous burden to be the next of kin of a substance abuser. Health personnel can help the next of kin to find strategies that maintain and improve their mental health.

Background: Substance abuse can place an enormous burden on the next of kin of the substance abuser.

Purpose: The purpose of the study was to examine the level of burden, use of coping strategies and mental health, and the associations between these variables, among the next of kin of substance abusers.

Methodology: We conducted this quantitative cross-sectional study in autumn 2014. Next of kin were recruited from treatment centres and support facilities in Telemark County. The questionnaire contained questions about demographic and substance abuse-related variables, the level of burden (the Burden Assessment Schedule 20), mental health (the General Health Questionnaire 12) and coping strategies (the Brief Coping Orientation to Problems).

Results: Forty-four women and three men (N=47) participated in the study. The mean age and years spent as the next of kin of a substance abuser were 50 and 15 years, respectively. The next of kin showed a high level of burden and psychological distress. They reported that they used both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies to manage their situation as the next of kin of a substance abuser. A higher level of burden showed significant associations with greater psychological distress and more use of planning, whereas greater acceptance of the situation showed an association with less psychological distress.

Conclusion: Next of kin of substance abusers show a high level of burden and psychological distress, and they use both problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies to cope with the challenges. When working with these next of kin, health personnel should focus on empowering them to make a conscious choice of adaptive coping strategies.

When someone in the family has a substance abuse problem, it affects his or her relationships, roles and ability to function. Each family member and the family as a system experience varying levels of burden (1–4). Next of kin must find ways to cope with the situation and take care of their own health.

Stress, coping and health are closely related (5), and long-term burden and stress can have both physical and psychological health effects (5–7). Alcohol problems are not just an individual problem, but also a significant relational challenge (2). A Japanese study, which included 543 next of kin of substance abusers, showed that over half of the next of kin had poor mental health (4). Next of kin of substance abusers have been shown to have both somatic and psychological problems in Norway as well (8–9). Simultaneous burdens such as worry, unpredictability, insecurity, financial strain, fear, guilt, shame, sorrow, stigma, humiliation, conflicts, consequences of irresponsibility, continually new crises, a feeling of always having to be vigilant, loss of social support, coping dilemmas and uncertainty about the future have been found in next of kin across cultures (10).

Strategies to cope with challenges

Coping strategies are thinking-related, intrapsychic (conscious or unconscious) or concrete behavioural strategies that are used to handle challenges, and are often divided into problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies. Problem-focused strategies include ways of acting in which the individual actively seeks solutions to the problems that are causing stress in order to change the situation. Emotion-focused strategies involve efforts to regulate feelings and reduce inner disturbance and discomfort resulting from the stress (11, 12). Coping theory, as seen in the work of Carver et al. (12), also distinguishes between adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies that cut across problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies. They emphasise that what is perceived to be maladaptive coping in one context may be appropriate and adaptive in another context (12).

According to prominent coping researchers such as Lazarus and Folkman (11), it is beneficial to bring attention to coping strategies as they lend themselves to cognitive and behaviour-oriented interventions and create opportunities for change. If coping strategies are used effectively, they can serve as a buffer against the negative effects that stressful situations can have on the individual (11). Being the next of kin of a substance abuser may be such a situation in which the person experiences a lack of control and lack of coping opportunities, and ineffective coping can cause the person’s health to deteriorate (13, 14). Next of kin often lack support, understanding and offers of assistance, and their own feelings and needs generally come second (14, 15).

Greater focus on next of kin

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on the next of kin’s own needs and adaptive coping in both the somatic and the mental health service (16–18). According to Vifladt et al. (19), the incidence of prolonged, complex health challenges has increased within the general population. Consequently, the focus must shift from the traditional treatment model in which experts ‘cure’ patients over to the patient’s and the next of kin’s own self-understanding, effort and coping. A proposal from the World Health Organization (WHO) to change the definition of health to ‘the ability to cope and self-manage’ also shows that coping is important (20).

Despite extensive research in the stress-coping field, few studies have been conducted on how the next of kin of substance abusers cope with their own life situation. Based on previous research on the associations between prolonged burden and diminished health, the purpose of this quantitative cross-sectional study was to examine the level of burden, the use of coping strategies and mental health in the next of kin of substance abusers, as well as the potential associations between the variables. The hypothesis was that the next of kin experience a high level of burden, that many of them have poor mental health, and that the level of burden and use of coping strategies are associated with perceived mental health.

Methods

Design

We conducted a quantitative cross-sectional study in the autumn of 2014. Next of kin of people with a substance abuse problem responded to standardised questionnaires about burden, mental health and coping. The questionnaires also contained questions about demographics and substance abuse-related variables in the respondent. A cross-sectional design does not produce causal explanations, only potential associations. However, in keeping with the principles of inductive reasoning, correlations support and reinforce a hypothesis (21).

Sample and recruitment

To be included in the study, participants had to be the next of kin (child, parent, stepparent, domestic partner/spouse, grandparent or sibling) of one or more substance abusers. Substance abuse includes the harmful use of illegal drugs, alcohol or non-prescribed medications. The participants had to be over the age of 16. Exclusion criteria were substance abuse in combination with severe mental illness, such as psychosis, or if the next of kin had his or her own serious substance abuse problem.

We invited the next of kin to take part in the study who had been in contact with outpatient clinics in the mental health service and cross-disciplinary, specialised addiction treatment and who had participated in an open meeting place, a counselling centre and a special interest organisation for substance abusers and their families in Telemark in the period from September to December 2014.

Participants received an information sheet, invitation, informed consent, self-reporting questionnaire and a stamped, addressed envelope from therapists and contact persons in the above-mentioned institutions and organisations, which they were asked to return to the researchers.

Ethics and privacy protection

The study was conducted as part of a master’s degree project in mental health care at Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences and was pre-approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South-East Norway. All the participants gave their informed written consent. The responses were anonymous and returned to the researchers. The participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without repercussions.

The questionnaires

Demographic and substance abuse-related variables

We registered gender, civil status, educational level, employment status and income. Regarding the substance abuse-related variables due to the life situation of the next of kin, the questions asked how often the substance abuser and next of kin had contact, whether they lived together with the substance abuser, how they experienced the consequences of the abuse, the assistance they gave to the substance abuser, whether they had grown up in a home with substance abuse, and the type of substance the abuser primarily used.

Burden

The type and extent of burden on the next of kin were measured with the Burden Assessment Schedule (BAS 20) (22). The BAS contains 20 questions distributed across five variables: 1) impact on well-being, 2) whether the care is appreciated, 3) impact on relations with others, 4) perceived severity of the disease and 4) impact on marital relationships. Each variable has four questions with a three-part scale: ‘not at all’ = 1 or 3, ‘to some extent’ = 2 and ‘very much’ = 3 or 1. The total score per variable ranges from 4–12 and the overall score from 20–60. Higher scores indicate a greater or increased burden.

It was also possible to choose the response ‘not applicable’. In this study, the variable ‘impact on marital relationships’ was only relevant for five next of kin and was therefore not included in the calculation of the total BAS score. Thus, the total score in the study consisted of four variables with a total score ranging from 16–48. Only the total score was used in the study. When a variable had one missing response or ‘not applicable’ was selected, the value was replaced with a mean score, known as the ‘case mean substitution technique’ as described by Fox-Wasylyshyn and El-Masri (23). When two or more questions per variable in the BAS had missing responses or ‘not applicable’ was chosen, the respondent’s scores on the relevant variables were excluded. A total of 41 respondents were included in the overall BAS score.

Weimand, who translated the BAS into Norwegian (24), gave us permission to use the instrument. Sell et al. (22) described validity and reliability as acceptable in the original target group.

Mental health status

To measure mental health status, we used the General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ 12), a screening instrument for identifying psychological distress and general symptoms of poor mental health (25). GHQ 12 consists of 12 questions. Six of these are worded positively and have the following response choices: 0 = ‘better than usual’, 1 = ‘same as usual’, 2 = ‘less than usual’ and 3 = ‘much less than usual’. The other six questions are worded negatively and have the following response choices: 0 = ‘not at all’, 1 = ‘no more than usual’, 2 = ‘rather more than usual’ and 3 = ‘much more than usual’.

We used two different scoring systems: a) A Likert-type scale with a total score from 0–36, in which a high score indicates diminished well-being, problems and reduced functional capacity to a degree that indicates a potential mental health disorder, and b) As a screening instrument for identifying mental illness, we also used a single scoring method, i.e. the Likert scores were dichotomised as follows: 0 and 1 = 0, whereas 2 and 3 = 1, with a total score from 0–12. In line with previous studies, we chose a score of >4 as the cut-off for caseness (the indication of significant mental illness) (26).

Coping

The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems (Brief COPE) (27) is an abridged version of the COPE Inventory (12) and measures various coping strategies for managing and dealing with stress. Brief COPE consists of 28 questions distributed among 14 scales that measure various coping strategies: active coping, planning, venting, use of instrumental support, use of emotional support, acceptance, positive reframing, denial, behavioural disengagement (giving up), self-distraction, self-blame, humour, religion and substance use. All of these are combined into problem-focused (PF) and emotion-focused (EF) strategies, as well as into adaptive (A) and maladaptive (MA) strategies (12). Each the strategies is measured with two questions in which respondents state how often they use the various strategies to cope with stress – in this case related to being the next of kin of a substance abuser. Each question is scored on a scale from 1–4: 1 = ‘I haven’t been doing this at all’, 2 = ‘I’ve been doing this a little bit,’ 3 = ‘I’ve been doing this a medium amount’ and 4 = ‘I’ve been doing this a lot’. The total score is from 2–8. The higher the total score, the more the respondent used the strategy. The Brief COPE was translated into Norwegian by Kristiansen (28), who gave us permission to use the instrument.

Analysis

Non-parametric tests were used because the data did not have a normal distribution and the sample was relatively small. We used descriptive analyses: frequencies (n) with percentages (%) to present demographic and substance abuse-related variables, median (MD) and quartile differentials (QD) to present the scores on the continuous scales: BAS, the various coping strategies in Brief COPE and GHQ 12.

We performed bivariate correlation analyses between BAS, the strategies in Brief COPE and GHQ 12 using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho). Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure the internal consistency of the standardised measurement instruments, and showed good values: BAS (0.87), Brief COPE (>0.78 on all scales) and GHQ 12 (0.89). A significance level of <0.05 was used for all the tests. The analyses were performed with SPSS 22.

Results

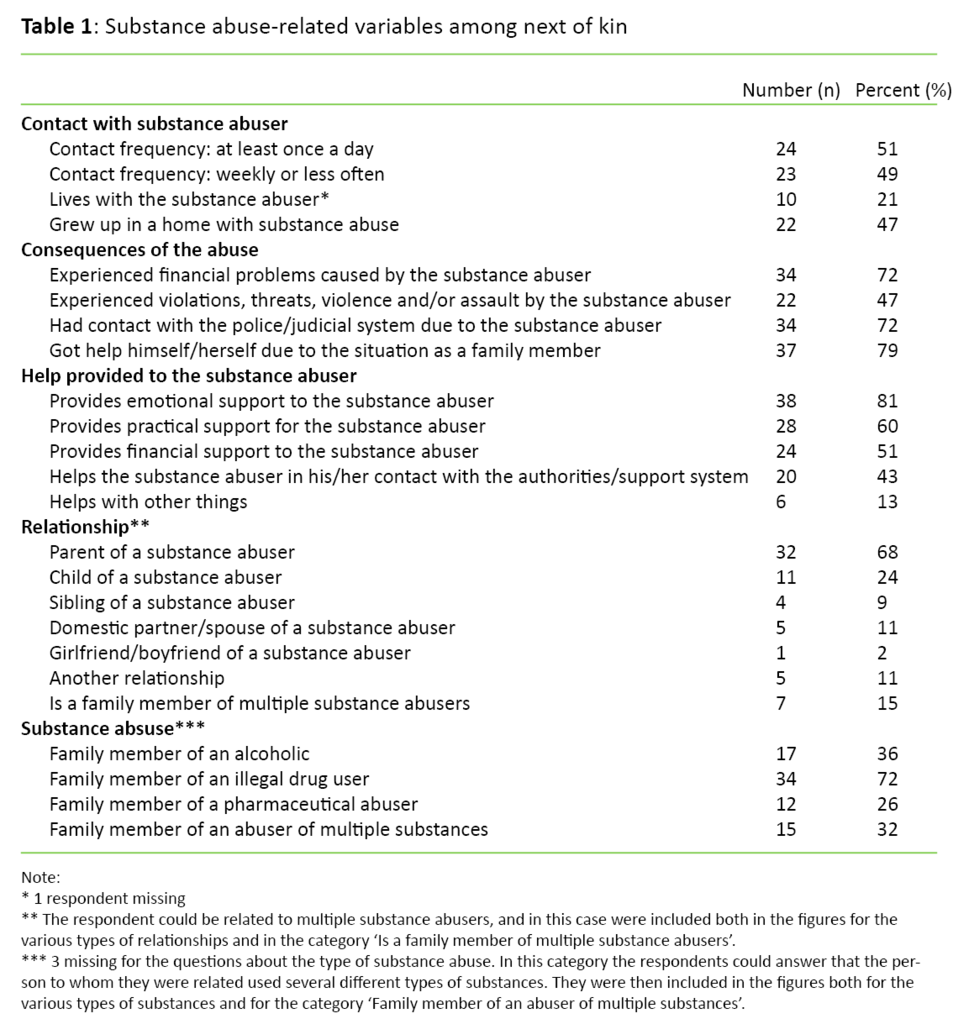

Of 47 respondents, 44 were women (94 per cent). Twenty-five (53 per cent) were married or cohabiting. The mean age of the sample was 50 years (SD 14), and the mean number of years as the next of kin was 15 years (SD 12). Twenty respondents (43 per cent) were employed or undergoing education, and 27 respondents (57 per cent) did not have permanent, daily employment. Fifty-one per cent had an annual income of less than NOK 450 000. Substance abuse-related variables are presented in Table 1.

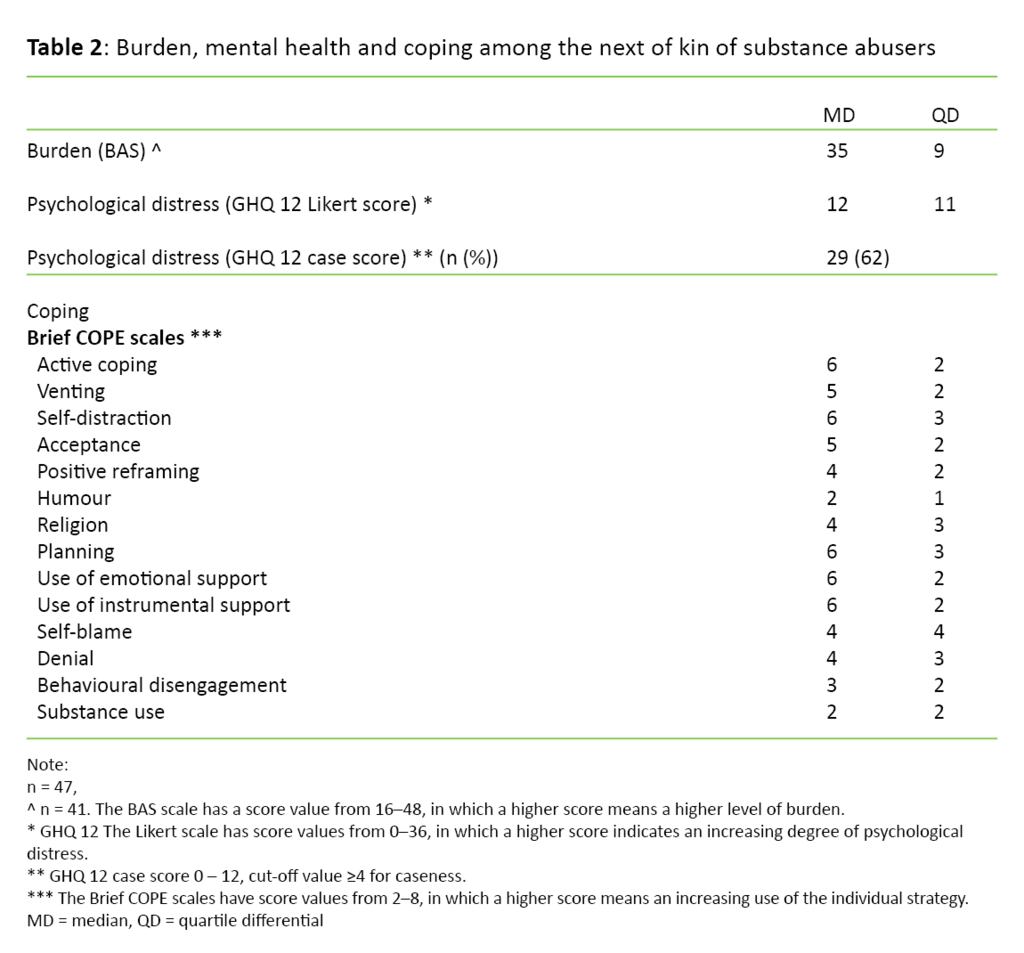

The results showed that next of kin are a group that experiences a significance burden and high level of psychological distress. As shown in Table 2, the median value of the total BAS score was 35 (QD 9), the GHQ 12 median value was 12 (QD 11), and 29 respondents (62 per cent) had a GHQ 12 score of >4, i.e. above the case score, which indicates clinical mental illness and a need for assistance.

The median values on the coping scales varied from 2–6. This means that all the coping strategies were used to some extent. The problem-focused strategies of planning, instrumental support and active coping, together with the emotion-focused strategies of self-distraction, emotional support and acceptance, were used the most. Except for self-distraction, these are defined as adaptive strategies. The emotion-focused strategy of humour, which is categorised as an adaptive strategy, was used the least (Table 2).

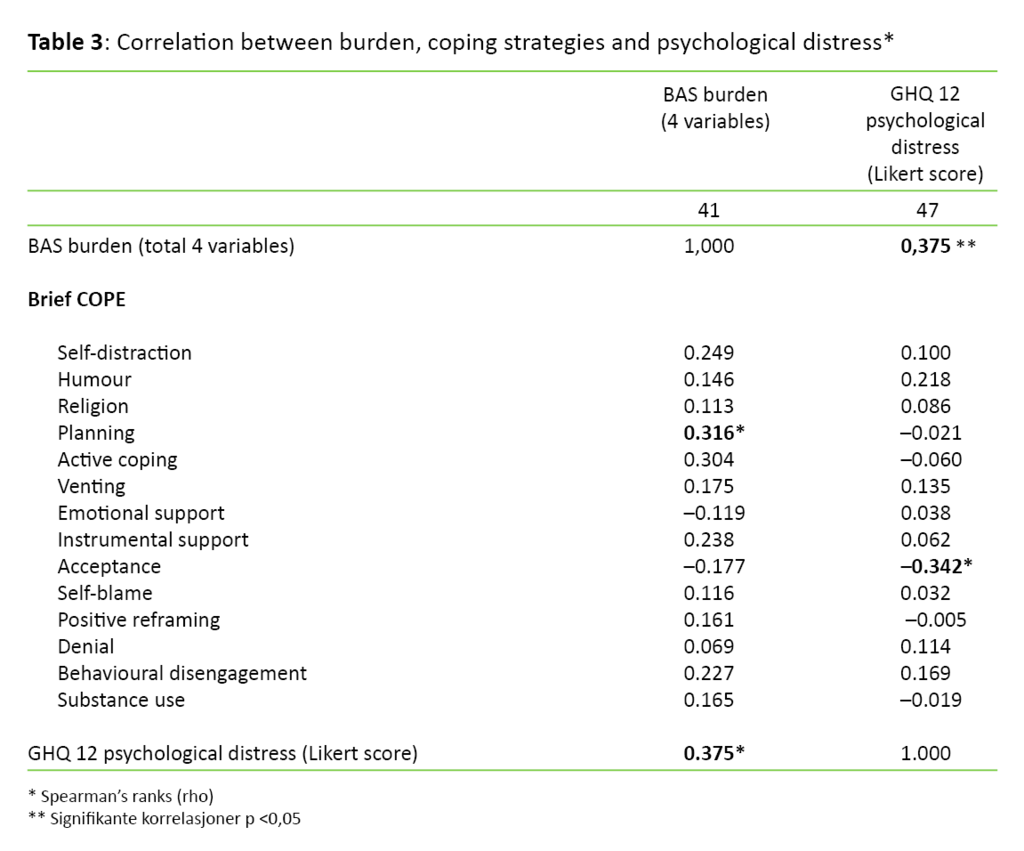

The correlation analyses showed that a higher level of burden is associated with greater psychological distress (rho = 0.375, p <0.05). Greater use of the coping strategy ‘acceptance’ showed an association with less psychological distress (rho = –0.342, p <0.05), and an increased burden with greater use of the coping strategy ‘planning’ (rho = 0.316, p <0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

The study showed that next of kin of substance abusers experienced a significant level of burden and major psychological distress. Sixty-two per cent reported psychological distress corresponding with a need for treatment. A higher level of burden showed an association with more psychological symptoms and greater use of the coping strategy ‘planning’. Notably, the problem-focused strategies of planning, instrumental support and active coping, as well as the emotion-focused strategies of self-distraction, emotional support and acceptance, were used the most. Greater use of acceptance showed an association with less psychological distress.

The respondents had a high level of burden, and many reported psychological distress. The results showed an association between the level of burden and psychological distress. The findings confirmed previous research results, as well as the hypothesis that there is an association between prolonged burden and diminished health in the next of kin of substance abusers (2, 4, 8, 9, 29). In the stress-strain-coping-support model, the nature of the burden, the substance abuse and the consequences of the substance abuse are viewed as variables that have a greater impact on next of kin and their mental health over time than the use of coping strategies. Our findings are in line with this. It is also reasonable to assume that mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression can reduce the next of kin’s capacity to cope with the burden caused by the substance abuse. They may therefore perceive the substance abuse as an even greater burden. This may be a reason that the sample has mental health disorders at a rate six times higher than the Norwegian population as a whole (30).

Next of kin’s use of coping strategies

Next of kin of substance abusers face continually new, challenging situations without a means of dealing with them. The advantages and disadvantages of various strategies must be assessed and can contribute to coping dilemmas, as Orford et al. describe in detail (10, 31). The next of kin must make choices, and they must plan how they can best manage the situation at hand. This may explain the increased use of the problem-focused strategy of planning when the burden increases, as reported in the study. In addition to planning and seeking out instrumental support, which involves obtaining information, assistance and guidance, active coping was among the most widely used problem-focused strategies. Active coping includes direct action to try to solve the substance abuse problem or reduce its negative consequences.

Our findings about a behaviour aimed at actively solving the problem are in line with previous research findings emphasising that next of kin use coping strategies that can help to change and improve the situation (3, 8, 10). There were far more female than male respondents in the study, and most of them were parents of a substance abuser. Previous research shows that women involve themselves more in the substance abuse problem than men (8, 10, 32). Research also shows that being the parent of a substance abuser results in an additional sense of responsibility and motivation to take action (33), and may explain the use of problem-focused strategies in this sample.

Next of kin’s acceptance of the situation

The goal of emotion-focused strategies is to manage the mental stress activated by the situation at hand. In coping theory, these strategies are considered to be the most adaptive to use when the individual has little control over the burden (12). Being the parent of a substance abuser is such a situation. Acceptance and use of emotional support are defined as adaptive, emotion-focused strategies as opposed to the maladaptive strategy of self-distraction in which the goal is to avoid thinking about the cause of the perceived stress (12). It is meaningful that these emotion-focused strategies are used a great deal by the group of next of kin. It seems particularly important to use acceptance in situations that are difficult to change (12). The results show that the more the next of kin accept the situation, the less psychological distress they report. This may be related to the observation that next of kin who accept their situation and acknowledge their problems are able to deal more expediently with their situation by using adaptive, problem-focused strategies.

From this perspective, the use of adaptive, problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies are linked together and are in line with previous research (12). Carver et al. (12) note, however, that seeking emotional support may be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it may be beneficial to promote greater use of problem-focused strategies. However, if the next of kin remains in a position of seeking support without actively using problem-focused strategies, the strategy may be regarded as maladaptive. On the other hand, self-distraction is generally regarded as a maladaptive strategy (12). However, it may also be viewed as adaptive if using the strategy can help individuals to experience periods of rest, joy, restitution and healing, even though they are in a long-term, stressful situation without the possibility of a solution.

Trying to solve unsolvable problems?

Next of kin of substance abusers do not always find that their efforts to cope have the desired outcome (3, 8, 31), nor do they always find that extensive use of problem-focused strategies are the most adaptive in terms of their own mental health when the burden variables are outside of their own control. Thus, a high level of psychological burden can be explained in part by the next of kin’s attempt to change and solve problems they cannot solve, e.g. trying to get the loved one to stop the abusive behaviour. Whether more emotion-focused coping would be more adaptive for this group of next of kin is a question that remains unanswered. However, strategies that may promote a high level of negative stress at a single point in time may nonetheless be best in the long term. This has been asserted in research on people’s resiliency during crises and difficult life situations (34).

Lazarus and Folkman (11) emphasise that it is necessary to use complementary coping strategies, such as problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies. Next of kin of substance abusers use both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies, and the findings are therefore in line with previous research (2, 8, 10, 11).

In accordance with clinical experience and previous research (8, 9, 10, 31, 33), it also appears that the substance abuser’s drug and alcohol use, pattern of abuse, behaviour, and physical and mental health are significant for the next of kin’s mental health. The same is true for their own abilities, learned patterns of reaction, assistance and relief, social expectations, roles and relational interaction between the next of kin, other social circles and the substance abuser. In addition, traditional versus modern familial roles, the family’s material living conditions, gender and cultural norms are significant for mental health.

The findings from the study emphasise the importance of acknowledging the next of kin’s attempt to cope and at the same time offering support, information and assistance so that they can find adaptive coping strategies to maintain and improve their mental health.

Strengths and weaknesses

The study used well-tested measurement tools with good psychometric properties. Internal consistency measured with Cronbach’s alpha showed high reliability. Distribution of most of the continuous scales was unequal, and the sample was relatively small. As a result, non-parametric statistical analyses were performed. Compared with parametric tests, non-parametric tests are somewhat less sensitive to correlations (25). Unequal distribution, a relatively small number of participants (n), and the uncertain number of non-responders reduce external validity. This means that we should be cautious about drawing generalisations from this study. What strengthens the assumption that the findings can be generalised is that they largely correspond with previous research in the field.

The sample was a cluster and convenience sample, but it can be assumed that the respondents represented a diversified group since they had sought out various types of assistance. It can be viewed as a strength that the recruitment of participants was random, which usually reduces the risk of sample bias (36).

Conclusion

The results show that the next of kin of substance abusers experience a significant burden and have a high risk of mental health problems. The study shows that a higher level of burden is associated with an increased level of mental health problems and the use of the coping strategy ‘planning’. The next of kin used both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies to manage the situation. Acceptance showed a positive association with better mental health. When next of kin come in contact with the support system, the support system should focus on acknowledging their attempts to cope with the situation. The support system should also direct attention towards awareness-raising, support, counselling and assistance to find the most adaptive ways of coping in the individual’s unique situation.

The complementary findings in the study point in the same direction as previous qualitative research results. However, further research is needed. In particular, we know little about men and siblings who are the next of kin of substance abusers. Longitudinal studies can increase knowledge about the coping process in a longer-term perspective. They can also shed light on which causal connections this knowledge has with burden and mental health.

References

1. Lindgaard H. Voksne børn fra familier med alkoholproblemer: mestring og modstandsdyktighed. Aarhus: Center for rusmiddelforskning, Aarhus Universitet. 2002.

2. Lindgaard H. Afhængighed og relationer: de pårørendes perspektiv. Aarhus: Center for Rusmiddelforskning, Aarhus Universitet. 2008.

3. Hansen FA. Rusmisbruk i et familieperspektiv. Hvilke utviklingsmessige konsekvenser kan det få for barn. Skien: Borgestadklinikken. 1985.

4. Morita N, Naruse N, Yoshioka S, Nishikawa K, Okazaki N, Tsujimoto T. Mental health and emotional relationships of family members whose relatives have drug problems. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai zasshi. Japanese journal of alcohol studies & drug dependence. 2011 Dec:525–41. PubMed PMID: 22413561.

5. Rice VH, editor. Handbook of stress, coping, and health. Implications for Nursing Research, Theory, and Practice. Los Angeles: SAGE. 2012.

6. Ursin H, Eriksen HR. Cognitive activation theory of stress (CATS). Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2010:877–81. PubMed PMID: 20359586.

7. Barboza Solis C, Kelly-Irving M, Fantin R, Darnaudery M, Torrisani J, Lang T et al. Adverse childhood experiences and physiological wear-and-tear in midlife: Findings from the 1958 British birth cohort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;17:738–46. PubMed PMID: 25646470.

8. Høie MM. Sorgen som aldri tar slutt: en kvalitativ studie av emosjonelle reaksjoner ved det å være foreldre til et barn som misbruker narkotika. M. Høie. 2005.

9. Nordlie E. Alkoholmisbruk – hvilke konsekvenser har det for familiemedlemmene? Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2003;1:52–4.

10. Orford J, Natera G, Copello A, Atkinson C, Mora J, Velleman R et al. Coping with alcohol and drug problems. The experiences of family members in three contrasting cultures. East Sussex: Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group. 2005.

11. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. 1984.

12. Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1989;56:267–83. PubMed PMID: 2926629

13. Ursin H, Eriksen HR. The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:567–92. PubMed PMID: 15041082.

14. Høie MM, Drottz-Sjøberg B-M. Forbannede, elskede barn: narkotikamisbruk sett i lys av pårørendes erfaringer. Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk. 2007.

15. Bøckmann K, Kjellevold A. Pårørende i helsetjenesten. En klinisk og juridisk innføring. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. 2010.

16. Helsedirektoratet. Pårørende – en ressurs: veileder om samarbeid med pårørende innen psykiske helsetjenester. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet. 2008.

17. St.meld. nr. 25. Åpenhet og helhet. Om psykiske lidelser og tjenestetilbudene. Oslo: 1996–1997.

18. Helsedirektoratet. Sammen om mestring: veileder i lokalt psykisk helsearbeid og rusarbeid for voksne: et verktøy for kommuner og spesialisthelsetjenesten. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet. 2014.

19. Vifladt EH, Hopen L, Berg KA. Helsepedagogikk: samhandling om læring og mestring. Oslo: Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for læring og mestring ved kronisk sykdom. 2004.

20. Hubert M, Knottnerus, J.A., Green, L et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343.

21. Kvernbekk T. Vitenskapsteoretiske perspektiver. In: Lund T (ed.). Innføring i forskningsmetodologi. Oslo: Unipub. 2002:19–78.

22. Sell H, Thara R, Padmavati R, Kumar S. The burden assessment schedule. WHO. 1998.

23. Fox-Wasylyshyn SM, El-Masri MM. Handling missing data in self-report measures. Research in Nursing & Health. 2005;28:488–95. PubMed PMID: 16287052.

24. Weimand BM. Sammenvevde liv: å være pårørende til personer med alvorlig psykisk lidelse. Pårørendes livssituasjon og møte med psykiske helsetjenester, fra pårørendes og sykepleieres perspektiv. Oslo, Skien: Landsforeningen for pårørende innen psykisk helse, Nasjonalt senter for erfaringskompetanse innen psykisk helse. 2013.

25. Goldberg D, Williams P. A user's guide to the general health questionnaire. London: Nfer-Nelson. 1988.

26. Nerdrum P, Geirdal AØ. Psychological distress among young Norwegian health professionals. Professions & Professionalism. 2013;3.

27. Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. PubMed PMID: 16250744.

28. Kristiansen E, Roberts GC, Abrahamsen FE. Achievement involvement and stress coping in elite wrestling. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2008;18:526–38. PubMed PMID: 17555543.

29. Kristiansen R, Myhra A-B. Hvem er de pårørende som søker behandling, og hva slags belastninger rapporterer de om? Kartlegging av pårørendepasienter ved Borgestadklinikken 2009–2011. Skien: Kompetansesenter rus – region sør, Borgestadklinikken. 2013.

30. Nes, LS, Clech-Aas, J. Psykisk helse i Norge. Tilstandsrapport med internasjonale sammenhenger (rapport 2). Oslo: Nasjonalt folkehelseinstitutt. 2011.

31. Orford J. Addiction Dilemmas. Family experiences from literature and research and their challenges for practice. Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. 2012.

32. Storbækken S, Iversen E. Alene sammen: om hjelpebehov hos pårørende til rusmiddelavhengige. Bergen: Stiftelsen Bergensklinikkene, Kompetansesenter rus, Region vest. 2009.

33. Usher K, Jackson D, O'Brien L. Shattered dreams: parental experiences of adolescent substance abuse. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2007;16:422–30. PubMed PMID: 17995513.

34. Hauser ST. Understanding resilient outcomes: Adolescents lives across time and generations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:1–24.

35. Pallant j. SPSS Survival Manual, 5. ed. Open University Press; 2013.

36. Johannessen A., Tufte P.A, Christoffersen L. Introduksjon til samfunnsvitenskapelig metode. 4. ed. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag. 2010.

Comments