The experiences of bereaved relatives on receiving the intensive care diaries of their loved ones

The bereaved felt that they maintained a bond with their deceased family member through diaries that had been kept for the patients during their stay in ICU. The diaries also helped impart structure on a chaotic time and made it easier for the bereaved to vent their feelings.

Background: Patients and their relatives are put under great stress whenever acute and critical illness dictates admission to an intensive care unit. Intensive care patients can be left with blurred memories of their time in intensive care, which is why registered nurses keep diaries for them. When patients die in ICU, their diary is offered to their relatives. So far, we have little knowledge about the experiences of the bereaved on receiving such a diary.

Objective: To increase our knowledge about the experiences of bereaved family members in relation to receiving the intensive care diary of a deceased patient.

Method: The study had a qualitative design which reflects a phenomenological approach. Invitations were issued to bereaved family members from three different intensive care units in a Norwegian university hospital. We conducted in-depth interviews with five bereaved family members 6–18 months after their loved one had died. We also included an email received from one participant. Audio recordings were made of each interview and these were then transcribed verbatim. We conducted the analysis using Giorgi’s descriptive phenomenological method.

Results: All the bereaved participants in the study were dealing with grief. The diaries had been long awaited and were used for comfort and support. While receiving the diary triggered strong emotions, none of the informants would have preferred not to have had it. Some wished that the diary had been handed over at an earlier point. The pictures were felt to be powerful and precious. Reading the diary made the bereaved aware of the care that their loved one had received from the ICU nursing staff, and this meant a lot to them. The diaries helped impart structure on a chaotic time and enabled the bereaved to vent their feelings.

Conclusion: When patients die in ICU, intensive care diaries can provide support for the bereaved during the grieving process.

When patients die in intensive care, it has a major impact on their loved ones. These deaths are often sudden and unexpected, and the bereaved are at risk of developing anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1, 2).

Having learnt more about patients’ challenges after discharge from ICU, intensive care nurses in the Nordic countries started keeping diaries for their patients in the early 1990s (3). The practice of keeping diaries for intensive care patients has since been adopted by other countries (4–6).

The purpose of the diary was originally to help fill the gaps in the patients’ blurred memories of their stay in ICU and to help them process their experiences (7). Gradually, research demonstrated that these diaries were of benefit to both patients and their relatives as they sought to cope in the aftermath of critical illness (8, 9).

The pictures and stories from the patient’s time in ICU helped to prevent anxiety, depression and PTSD (10). In 2011, Norway adopted national diary recommendations. The diaries were to be offered to the bereaved family members because the feedback from specialists in the field was that the diaries were helpful to the bereaved in their grieving process (11).

Objective of the study

Earlier research into intensive care diaries has tended to focus on the experiences of surviving patients and their relatives (10). There are currently few studies that deal with the intensive care diary experiences of bereaved family members (12–15).

The study’s objective was therefore to increase our knowledge about the experiences of bereaved family members who had received the intensive care diary of a loved one after he or she had died.

Method

The study has a qualitative design and takes a phenomenological approach, and we used a strategic sample (16). The inclusion criteria were for participants to have received a diary after the death of a patient, be registered as the patient’s next of kin and be over 18 years of age. The bereaved were recruited from three intensive care units in a Norwegian university hospital.

One intensive care nurse in the diary team at each ICU issued invitations to take part in the study in the early autumn of 2017. A total of 21 invitations were sent out and we received six positive responses. Three men and three women were included in the sample. They were between 35 and 55 years of age and either the spouse, partner, child or parent of the patient.

The patients had received different diagnoses and their time spent in ICU varied from a few days to several weeks. Data were collected by means of in-depth interviews conducted in the autumn of 2017 and in the early winter of 2018. The interviews were conducted by the first author, who is an ICU nurse with extensive experience of intensive care diaries.

Our interview guide was edited after two pilot interviews. Each interview lasted between 25 and 55 minutes and audio recordings were made of them all. Three interviews were conducted in the participants’ respective homes, one in the hospital and one over the phone. Once the interviews had been completed, the main points were summarised in liaison with each participant to ensure that the interviewer had understood them correctly.

The interviewer then recorded her reflections on the interview situation. All interviews were transcribed verbatim (17). Additionally, the account of one participant was received by email and this was included in the data material.

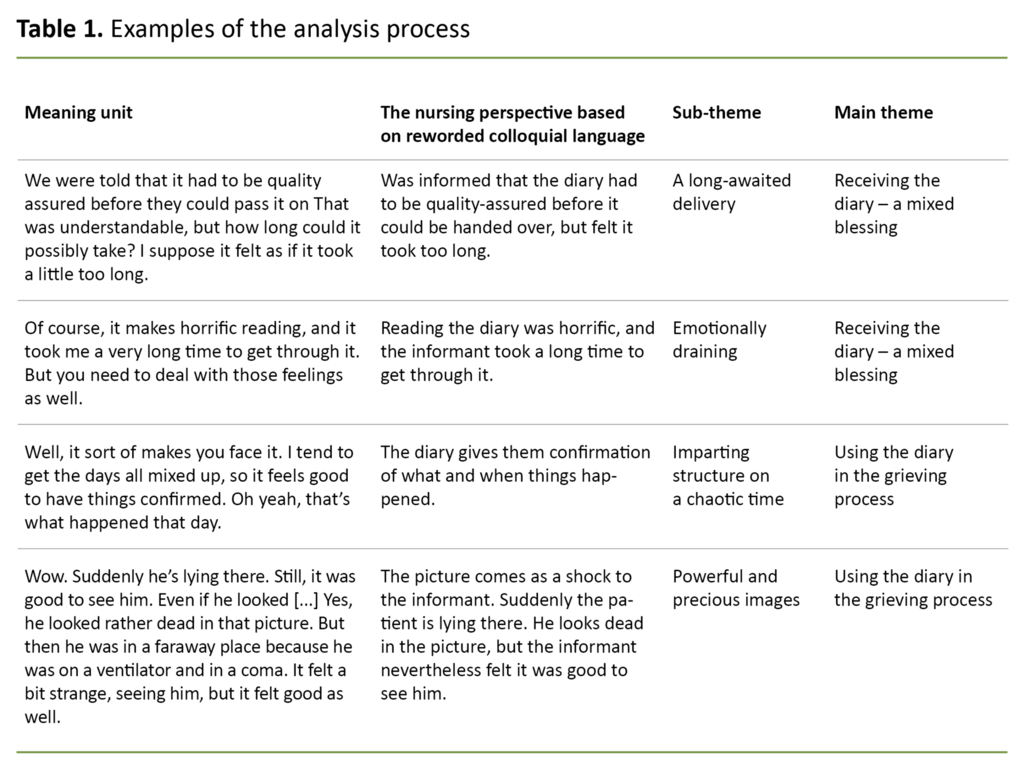

Analysis

We analysed the data using Giorgi’s descriptive phenomenological method. We started by reading the interviews in order to form an overall impression. We went on to split the texts into meaning units whenever there was a change of semantic content.

The colloquial language of the meaning units was rephrased and condensed based on a nursing perspective. Units that conveyed similar meanings were grouped together under preliminary themes for each interview.

We then categorised the preliminary themes across all interviews and in line with the objective of the study. Two main themes emerged from this process, each with several sub-themes, which in combination gave new insight into the studied phenomenon (18). We met regularly to discuss our findings and analytic endeavours in order to increase the credibility of the end results.

Ethical considerations

People who have been bereaved are vulnerable, but studies also show that the bereaved may find research participation to be ‘therapeutic’ (19). The participants were informed about the study’s objective, their right to withdraw, and that all identifiable personal information would be treated confidentially and anonymised on publication.

The transcripts were de-identified and stored on a private password-protected computer (16). The Heads of Clinic approved the project before it commenced. The study was recommended by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), project number 54802.

Results

Two main themes emerged from the analysis, which in combination suggested mixed experiences among the participants with using the diary in the grieving process. The bereaved felt ambiguous about receiving the diary. On the one hand, they were grateful to have received it, while on the other hand, the diary triggered powerful emotional reactions.

All of the bereaved were still in deep grief, and they were using the diaries in their grieving process.

All of the bereaved were still in deep grief, and they were using the diaries in their grieving process. All of them had read the diary, but some had been reading it more often than others – ranging from once on receipt of the diary to multiple times. The two main themes will be presented with a number of sub-themes.

Receiving the diary – a mixed blessing

In summary, taking receipt of the diary was a positive experience, if emotionally draining.

A long-awaited delivery

The diaries were received in the post, as a signed-for parcel. The participants had been expecting the diary’s arrival and therefore knew what it was on delivery. None of them had any objections to picking up the diary from the post office as it would have been more challenging and cumbersome to have picked it up from the hospital. Several explained this preference by referring to the long journey involved.

They were also grateful for the opportunity to sit down with the diary on their own: ‘I felt it was quite alright, really. Being able to open it and browse through on my own. Getting through it was hard going. It took an awfully long time.’

One of the participants felt that the diary should have been handed over with the patient’s personal belongings, because it belonged to the patient. Some felt that the waiting time between the patient’s death and receiving the diary was too long. One participant had been told that it would take one to two months, but three months passed before she received the diary. She expressed this as follows:

‘We were told that it had to be quality assured before they could pass it on. That was understandable, but how long could it possibly take? I suppose it felt as if it took a little too long, but maybe it makes sense.’

Emotionally draining

Receiving the diary was an emotionally draining experience for all participants. They felt a sense of shock, anxiety and panic, yet they were also looking forward to receiving it. The opportunity to spend as long as they needed on going through it was reassuring. One of the participants explained it like this:

‘Oh dear, there it was. My god, it was like an instant shock. Just had to sit down and breathe a little. And then open it. When I had looked through it, it was fine. And afterwards I had to put it to one side for a while.’

Receiving the diary was an emotionally draining experience for all participants.

Most of them described receiving the diary as a challenging experience. Reading the diary made them relive the time they had spent in the intensive care unit. But all the same, they were very grateful for having received it.

One of the participants explained that going through the diary was something she simply had to do: ‘And then it was lying on the kitchen table. I wasn’t entirely sure, but opened it and quickly leafed through it. It was very beautiful, and then I put it away.’

The participant explained that after reading the diary, it was as if she had to start her grieving process all over again.

Using the diary in the grieving process

The participants were grieving for their loved ones and used the diary in various ways to process their loss. The care that the patient had received became evident to them through the words and pictures. The diary helped them clarify their memories of a traumatic period and put a structure to the various events that had taken place during the stay in ICU.

Powerful and precious pictures

The photographs were the parts of the diary that were cherished the most by the participants, because most of them had not themselves been taking pictures of the patient while in hospital. Although the patient looked different in the pictures, they meant a lot to the bereaved:

‘You don’t take pictures in hospital like you do elsewhere in life. Photographing your kids, at weddings and such like. But the fact that the nurses do, I believe that’s important.’

It was a powerful experience for the relatives to look at the pictures of the patient. The participants assumed that the pictures had been selected with care and consideration because they were not distressing. Besides, they had all seen the patient while in hospital, often in a state that was even worse. The pictures gave an honest documentation of how critical the situation had been.

The participants were grateful that pictures had been taken of themselves with the patient. Where this had not been done, they blamed themselves. The pictures also conveyed important information about the time in intensive care.

One of the participants talked about an elderly family member who had been looking through the diary: ‘She finds it a bit difficult to read, but she sits looking at the pictures of her husband. Although he’s not looking that great, I think it has been really good for her.’

The diary had been shared with family and friends. The participants felt it was a positive experience to share it with others because this enabled them to remember the deceased.

Some family members had been shielded from seeing the diary – these were young children or elderly relatives. Others had not wanted to see the diary because they wished to remember the patient as he or she had been in life.

Evidence of the care provided towards the end

The ICU nurses had informed the relatives that they were keeping a diary for the patient, and that this might be of assistance to the patient after discharge from ICU. The participants were impressed with the accuracy of the nursing staff’s diary entries:

‘I think they’re honest. What the weather is like. That the family had been visiting. Some words about us. They saw what was happening, and then it becomes clear that it is pretty serious. We knew of course, but just the fact that they comment on being quite concerned.’

The participants were convinced that the diary would have been important to the patient had he or she survived, and that the patient would have been grateful for receiving the diary:

‘I can see from the diary that they cared. They made entries every day, and they wrote to him. About the things that happened. If he had survived, I think he would have appreciated it a great deal, because they talked to him, in a way, through the words.’

By reading the diary, the participants saw the level of care provided for the patient by the ICU nurses.

The participants were uncertain whether they would have wanted to make their own entries in the diary had they been given the opportunity to do so, because they felt that being there with the patient was enough. One family had been given sheets of paper for writing and drawing on, and these had been pasted into the diary by the nursing staff.

By reading the diary, the participants saw the level of care provided for the patient by the ICU nurses. The patient was described not only as a patient, but as a living human being. Afterwards, this was reassuring to the bereaved. One of the participants put it like this:

‘I’ve been giving it some thought. And now I’m starting to blubber. Yes, it’s like there is care in all the grief. What they wrote, they wrote in such a way that they really cared for him as he lay there. Even when I wasn’t there.’

It was clear to the participants from the handwriting and content that different people had been in charge of the patient’s care. This variation made the diary appear warm and personal. The participants were also reassured by reading about all the things that had been done to save the patient’s life.

The ICU nurses sought to ensure that the patient would be as comfortable as possible in a hopeless situation. One of the participants explained: ‘It’s very clear what they were trying to do. That they were working really hard to find out about things. That’s something that sticks in your mind afterwards.’

Structure in a time of chaos

During the interviews, it emerged that the participants’ concept of time had been disrupted by the patient’s period of illness, and that several of them found it difficult to keep track of time.

The period spent in ICU felt chaotic and confusing to them. The diary helped them keep track of the sequence of events. This imparted structure on the patient’s stay in ICU and helped the bereaved get a better understanding of the patient’s time in hospital:

‘The diary gives a better structure to everything that happened at a very hectic time. It’s difficult to put it all in perspective afterwards. After all, our memory is not our most reliable tool. Especially not in such a stressful situation.’

They used the diary to create a sense of order in the chaos they were experiencing.

The participants felt well taken care of in the hospital and they were kept informed by doctors and nurses along the way. The problem was that they immediately forgot what they had been told. The diary enabled them to keep track of which day the patient had been admitted to hospital, when x-rays were taken, who had visited, etc.

They used the diary to create a sense of order in the chaos they were experiencing. By putting the various events into a system, they felt they had a better grasp of the situation:

‘I get all confused about the time, you know. I’m still not completely sure what day it is. I actually wanted something or other to use as a reference point, ‘cause I had forgotten so much of what happened.’

They found that the diary helped them create a sense of order in the chaos they experienced in the immediate aftermath of the patient’s death.

Venting emotions

The diary was also used to open up to emotions. Some deliberately used it to help them grieve. They knew that whenever they were reading the diary, suppressed emotions would be triggered.

One of the participants explained as follows: ‘After all, I know how it all went. I get incredibly sad and start crying. It makes horrific reading, but you need to deal with those feelings as well.’

As time passed, family and friends became less preoccupied with talking about the deceased, but the participants felt they still needed to grieve. The diary gave them confirmation of what they had been through and they found acceptance that grieving was still allowed. The participants explained that they found support with their grieving in the diary:

‘Yes, in my experience it’s really important. Being able to bring it out when things are getting a bit tough. My thoughts are racing when I’m unable to sleep. It helps, it actually calms me down. I avoid those wretched thoughts: “What did I do wrong?”’

The diary helped the participants gain better control of difficult feelings and thoughts.

Discussion

It was clear from the interviews that the bereaved were still grieving. All human beings will experience grief in the course of their lifetime, but for some, losing a loved one is so traumatic that their health will be affected (20). When someone dies in ICU, this is normally as the result of acute and unexpected illness.

Studies show that it is more difficult to cope with unexpected death, and that the bereaved are more exposed to PTSD (2). This study shows that the diaries were used for support in the grieving process, thereby helping the bereaved find new meaning in their suffering (20).

Different responses to receiving the diary

There are many different ways of grieving. Every human being will react differently to the death of a loved one, even if the type of loss may appear to be similar (21). Our study showed there were many similarities between the participants’ experiences, but that they responded differently to receiving the diary.

Taking delivery of the diary was a long-awaited moment, but it was also emotionally draining. One of the participants explained that she had to start her grieving process all over again. Receiving the diary without recourse to psychological support may therefore have adverse consequences (22). The national recommendations point out that the diary should be accompanied by appropriate information when handed over to the bereaved (11).

Nevertheless, the bereaved expressed gratitude that they were able to sit down with the diary on their own, because it was a process they needed to go through. Reliving memories can be an intrusive experience and some need to keep thoughts of their bereavement at bay in order to cope with daily life (23).

In Norway, diaries are not disclosed to relatives while the patient is in intensive care because it forms part of the patient’s medical records (11). Consequently, the bereaved were not prepared for the diary content, although every one of them had read parts of it. In the study conducted by Johansson et al. (12), only four out of nine informants had read the diary, although they were familiar with the content.

Time may be a determining factor when it comes to how much diary-reading the participants had engaged in. In our study, the participants who were interviewed nearest to the bereavement date had spent least time reading the diary.

Acute grief is most pronounced in the first months following a bereavement, and in cases of traumatic death, the bereaved will feel a need to protect themselves against intrusive memories (24).

Denial and avoidance are normal grief reactions, but can also be early signs of PTSD, which the relatives of patients who die in ICU are at risk of developing (25).

Photographs were appreciated

All participants emphasised that the pictures were precious to them, because they had no photographs of their own of the patient. Nevertheless, it is advisable to exercise caution when pictures are included in the diary (14). The participants in our study felt that the pictures had been selected with care, since they did not seem distressing.

The diary helped the bereaved to talk about the deceased, thereby maintaining their association and bond with them. In the grieving process, efforts to create new meaning are important for the bereaved to cope with their new situation in life (21). Some studies have also shown that reading the diary can feel therapeutic, thereby reducing the incidence of PTSD (1).

The diary helped the bereaved to talk about the deceased, thereby maintaining their association and bond with them.

Forgetfulness is a common symptom after a traumatic incident, and the bereaved will therefore need to hear information repeatedly (8). The participants’ grasp on the sequence of events was still poor, but the diary provided accurate and considerate documentation of the patient’s illness.

Studies show that the bereaved feel a need to understand the progression of the illness and the cause of death in order to process it (26). The study participants highlighted the significance of the care that had been provided for their loved one and the fact that everything had been done to save the patient’s life.

According to studies of family needs in intensive care units after the death of a relative, one of the top priorities is the need to know that everything possible was done for the patient (27).

The diary could help in processing traumas

Traumatic experiences from the period spent on ICU can lead to sleeplessness and concentration difficulties, and guilt and self-recrimination occur relatively often (24). One of the participants made deliberate use of the diary to help with her insomnia, in that it helped to ease her spinning mind and reduce her feeling of guilt.

Studies show that bereaved relatives find it difficult to talk to other people about the time in intensive care, although they do feel a need to talk about the death (28). The diary was used as a tool for talking to other people about the period spent in ICU.

The diary also helped to impart structure on the chaos that many participants felt immersed in. Following up on bereaved relatives is important and has an impact on their grieving process (26). However, according to one Norwegian study, not all intensive care units offer a follow-up service for bereaved family members (29).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The study’s objective was to increase our knowledge and enhance our understanding of how bereaved family members experience taking receipt of the intensive care diary of a loved one after the patient’s death. The study sample was small, but the variation in age, gender and relationship to the patient nevertheless provided for rich, diverse and nuanced descriptions.

The study was strengthened by its open approach, an awareness of potential preconceptions and the fact that the first author conducted and transcribed all the interviews, which built a deep familiarity with the data material.

Conclusion and implications for practice

The diaries were used by the bereaved for comfort and support during their grieving process. The diary information helped impart a structure on the chaotic time that followed the death of their loved one. The diaries also helped them imbue their suffering with meaning and maintain a bond with the deceased. Intensive care units should provide more individual follow-up of bereaved relatives.

Handing the diary over to the bereaved appears to be good practice and should be prioritised. Every year, many patients die in Norwegian intensive care units. The grieving process that their loved ones go through should therefore receive more attention on the ward, but also in further research.

References

1. Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, Egerod I, Flaatten H, Granja C, et al. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Critical Care. 2010;14(5):R168.

2. Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–7.

3. Egerod I, Storli SL, Åkerman E. Intensive care patient diaries in Scandinavia: a comparative study of emergence and evolution. Nursing Inquiry. 2011;18(3):235–46.

4. Garrouste-Orgeas M, Perier A, Mouricou P, Gregoire C, Bruel C, Brochon S, et al. Writing in and reading ICU diaries: qualitative study of families’ experience in the ICU. Plos One. 2014;9(10):e110146.

5. Ewens B, Chapman R, Tulloch A, Hendricks JM. ICU survivors’ utilisation of diaries post discharge: a qualitative descriptive study. Australian Critical Care. 2014;27(1):28–35.

6. Roulin M-J, Hurst S, Spirig R. Diaries written for ICU patients. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(7):893–901.

7. Gjengedal E, Storli SL, Holme AN, Eskerud RS. An act of caring – patient diaries in Norwegian intensive care units. Nursing in Critical Care. 2010;15(4):176–84.

8. Nielsen A, Angel S. How diaries written for critically ill influence the relatives: a systematic review of the literature. Nursing in Critical Care. 2016;21(2):88–96.

9. Ullman AJ, Aitken LM, Rattray J, Kenardy J, Le Brocque R, Macgillivray S, et al. Intensive care diaries to promote recovery for patients and families after critical illness: a Cochrane Systematic Review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2015;52(7):1243–53.

10. Egerod I, Christensen D, Schwartz-Nielsen KH, Ågård AS. Constructing the illness narrative: a grounded theory exploring patients’ and relatives’ use of intensive care diaries. Critical Care Medicine. 2011;39(8):1922–8.

11. Storli SL, Gjengedal E, Eskerud RS, Holme AN, Synnevåg H. Nasjonale anbefalinger for bruk av dagbok til pasienter ved norske intensivavdelinger. Oslo: Norsk Sykepleierforbund; 2011. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/795419/Nasjonale%20anbefalinger%20for%20bruk%20av%20dagbok.pdf (downloaded 18.08.2019).

12. Johansson M, Wåhlin I, Magnusson L, Runeson I, Hanson E. Family members’ experiences with intensive care unit diaries when the patient does not survive. Scandinavian Journal Of Caring Sciences. 2018;32(1):233–40.

13. Bäckman CG, Walther SM. Use of a personal diary written on the ICU during critical illness. Intensive Care Medicine. 2001;27(2):426–9.

14. Combe D. The use of patient diaries in an intensive care unit. Nursing in Critical Care. 2005;10(1):31–4.

15. Bergbom I, Svensson C, Berggren E, Kamsula M. Patients’ and relatives’ opinions and feelings about diaries kept by nurses in an intensive care unit: pilot study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 1999;15(4):185–91.

16. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

17. Kvale S, Brinkmann S, Anderssen TM, Rygge J. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3rd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

18. Giorgi A. The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: a modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press; 2009.

19. Kentish-Barnes LN, McAdam AJ, Kouki AS, Cohen-Solal AZ, Chaize AM, Galon AM, et al. Research participation for bereaved family members: experience and insights from a qualitative study. Critical Care Medicine. 2015;43(9):1839–45.

20. Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–73.

21. Hoppes S, Segal R. Reconstructing meaning through occupation after the death of a family member: accommodation, assimilation, and continuing bonds. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010;64(1):133–41.

22. Phillips C. Use of patient diaries in critical care. Nursing Standard. 2011;26(11):35–43.

23. Frivold G, Dale B, Slettebø Å. Family members’ experiences of being cared for by nurses and physicians in Norwegian intensive care units: a phenomenological hermeneutical study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. 2015;31(4):232–40.

24. Sandvik O, Eriksen H, Bugge KE. Sorg. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2003.

25. Siegel DM, Hayes CE, Vanderwerker BL, Loseth GD, Prigerson GH. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(6):1722–8.

26. Kock M, Berntsson C, Bengtsson A. A follow‐up meeting post death is appreciated by family members of deceased patients. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2014;58(7):891–6.

27. Burr G. Contextualizing critical care family needs through triangulation: an Australian study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. 1998;14(4):161–9.

28. Mayer DD, Rosenfeld AG, Gilbert K. Lives forever changed: family bereavement experiences after sudden cardiac death. Applied Nursing Research. 2013;26(4):168–73.

29. Moi AL, Storli SL, Gjengedal E, Holme AN, Lind R, Eskerud R, et al. The provision of nurse‐led follow‐up at Norwegian intensive care units. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(13–14):2877–86.

Comments