Healthcare personnel as a source of comfort in recurrent ovarian cancer

Women with recurrent ovarian cancer endure their disease by finding solace in the hope of recovery. How can nurses provide consolation?

Background: The lives of women with recurrent ovarian cancer are marked by considerable existential distress. There is little specific knowledge about actions that nurses can take as they encounter these women, to relieve their existential distress.

Objective: The objective of this study is to identify potential sources of comfort for women with recurrent ovarian cancer, and to establish what nurses may be able to do to provide solace.

Method: We have adopted a qualitative method involving hermeneutic textual analysis. The study is based on deep interviews with five women, conducted after a three-week period of diary-keeping.

Results: Four main themes were found to provide comfort: hope of a future, being recognised, genuine presence, and self-preservation. Of these, ‘hope of a future’ was the most effective: hoping to be able to live for longer, to recover and to continue being important to other people. ‘Being recognised’ refers to being seen and remembered by healthcare personnel, and appreciating that life has a worth. ‘Genuine presence’ refers to healthcare personnel and other fellow human beings who provide comfort by being genuine and honest, for better or worse. ‘Self-preservation’ is a coping strategy that involves avoiding other people who are ill, and who may therefore provide a reminder of the seriousness of the disease.

Conclusion: Through diary entries and deep interviews, women with recurrent ovarian cancer talked openly about and reflected on what gave them solace. Our findings show that inter-human relationships are essential to finding meaning and worth in life. The study has implications for practice: Patients feel reassured when hospital staff recognise them. Awareness of one’s own role as a healthcare worker is important, as is being genuine and honest, and being knowledgeable about how to communicate. Who you are as a nurse, can provide consolation. Future studies should investigate existential comfort in greater depth and examine how this topic may be incorporated into the degree programme for nurses.

In 2015, a total of 520 new instances of ovarian and peritoneal cancer were recorded in Norway. At the time of diagnosis, 75 per cent were at an advanced stage. Median age at the invasive cancer stage was 65 years (1). The disease is then considered to be advanced, and 85–90 per cent will sooner or later suffer a relapse. From the time of recurrence, median survival is 12–24 months (2).

Anxiety and existential distress are heavily felt among the women (3–9), and the fear of dying is pervasive (10, 11). Nearly one third of the women who fear death, experience a loss of hope when life is nearing the end (8). When life is threatened, existential distress and fear arise (12). Existential questions abound: ‘What is life worth, what is the meaning of my life, who loves me, and how do I handle the fact that I am dying?’ (13)

Earlier research

When ovarian cancer recurs, women are offered life-extending chemotherapy administered at oncology outpatient clinics (1). In an earlier Norwegian study conducted by Hjulstad and Rannestad, women who had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer explained that when they failed to recover, they felt like second-rate patients in their encounters with the health service, because they were no longer as important (6).

Another study shows that while patients hope to be cured, nurses shy away from giving hope because they know the poor diagnosis. According to research, this is the reason why the interpersonal care relationship between nurse and patient changes when cancer recurs (4).

The objective of the study

According to research, consolation and support may help to turn around these women’s feelings of having been given a death sentence, thereby transforming their quality of life (5). Consolation and support have also shown a correlation with prolonged survival and a better quality of life (11, 9). In this current study, consolation is defined in accordance with Katie Eriksson’s phraseology: to console means to touch a person’s innermost longings and to help them regain an appetite for life, so that life, despite everything, has meaning (14).

Åsa Roxberg, who has conducted research on consolation, writes that there is no set answer to the question of what consolation is, and how to provide consolation (15). Is it possible to know how to give solace to these women? The objective of this study was to increase our knowledge of what constitutes consolation for women with recurrent ovarian cancer, and what nurses may do to provide solace.

Method

Design

The study has a qualitative design and takes a phenomenologic-hermeneutic approach. The data collection methods included the keeping of a diary and individual follow-up interviews. The women who took part in the study were recruited from the gynecology departments of two hospitals in South Norway, and through the Norwegian Gynecologic Cancer Association. The first author conducted the study in partnership with the second author, who provided supervision.

Sample

Eight ethnic Norwegian women aged between 49 and 82 took part in the study. The inclusion criterion was women who had suffered one or more relapses of ovarian cancer. All the women kept a diary and five of them were interviewed afterwards. A further four women notified us of their interest, but withdrew due to deteriorating health.

Ethics

The study has been approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics for south west Norway (reference number 2017/658), and the research departments at the two regional hospitals involved approved the study for internal recruitment. At the hospitals, recruitment was conducted by nursing staff. Women who enlisted through the Norwegian Gynecologic Cancer Association did so of their own accord after information had been posted on the association’s website or had been provided at a meeting of a local branch of the association. The participating women received written and verbal information before signing an informed consent form.

Data collection

Data were collected through interviews conducted in the period September 2017 to April 2018, subsequent to the informants having kept a diary for three weeks. The women were given a diary designed specifically for the study at the time of their recruitment. They were asked to make a note of any experience that gave them a sense of being consoled – of their existential distress being eased. They were also asked to indicate whether they were in hospital or at home at the time, and who and what provided consolation. It was left up to the women to decide how much to write and how frequent their entries were.

The interviews were conducted approximately one week after completion of the diary-keeping period. The diary entries gave no specific information about what it was that gave solace, but they provided a foundation for good interviews. For example, one of the women wrote: ‘Today I met a caring nurse, she consoled me.’ This entry gave rise to interview questions such as: ‘Tell me about the nurse who consoled you. What did she do or say to make you feel comforted?’

Several informants were able to say during the interview that ‘looking back on what I wrote, I can see that […]’. These statements suggest that the informants had gone through a process of reflection. Each interview lasted between 40 and 120 minutes. They took place in the informants’ home or over the phone, in accordance with their wishes. The transcriptions of the interviews make up approximately 50 pages of text which constitute the study’s data material.

Analysis

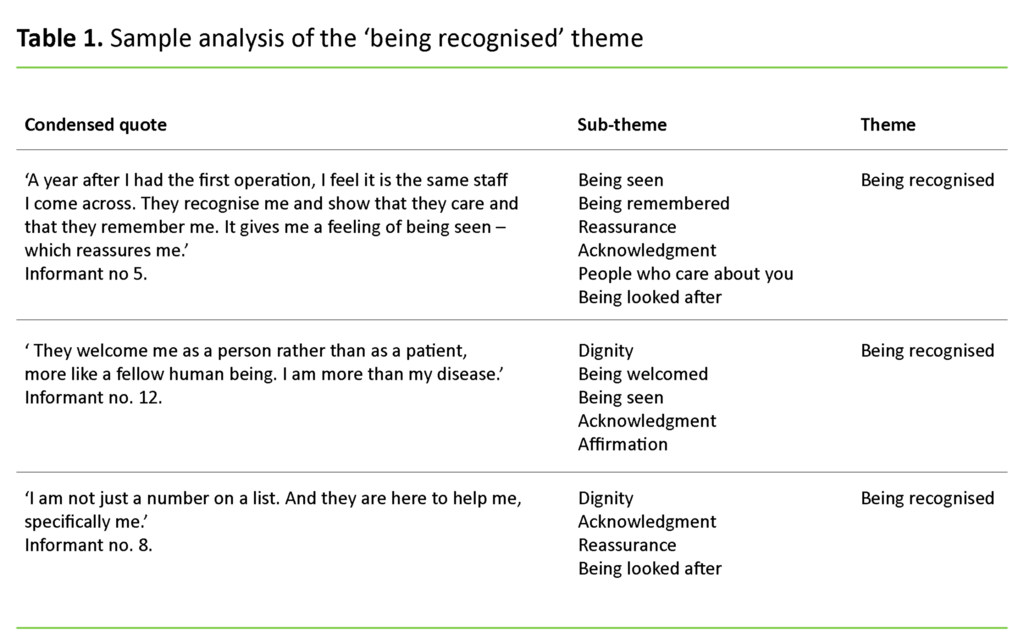

The data was analysed by means of systematic text condensation, as inspired by Giorgi and modified by Malterud (16). The analysis started with reading through all the texts. This gave an overall impression, which in turn helped us to identify different themes. The texts were thematically coded and units of meaning were brought together. The texts were then condensed into artificial first-person quotes that formed a number of sub-themes. These were in turn grouped into four main themes. A sample analysis of the ‘being recognised’ theme is included as Table 1.

Results

The study’s findings are grouped in four themes: hope of a future, being recognised, genuine presence, and self-preservation. All themes share a reliance on inter-human relationships for comfort to be instilled.

Hope of a future

The women who were interviewed were fully aware of the fact that they could not recover from their illness. The doctor had told them that the cancer would recur or get worse. Nevertheless, the most powerful source of comfort was one that gave hope of recovery and a longer life. One of them put it like this:

‘Consolation is the fact that there is still something they can do, that the doctor believes this will probably work, that I will manage this. Of course things can happen, but we don’t know anything about that.’ Another woman found consolation in God: ‘My faith in God is what comforts me the most. Perhaps I am dying, but it may also be that my life will continue. I believe in miracles.’ Hope is also associated with being lucky. ‘There was a girl on the news who the doctors had given up on, but she survived her cancer. Perhaps I will be just as lucky?’

The people who give the best comfort are those who communicate, confirm or share a belief in a future, whether it is the doctor, the nursing staff, friends or family. The hope of a future includes continued life, to mean something to others, and to be able to do something meaningful. Praise and the faith of others ensured that the hope was a source of comfort: ‘One of the doctors said that not many people live for as long as I have with this disease, and to me that is proof that God is present and has made sure that my disease goes the long way around.’

Several of the women emphasised that ‘when others want you to live, then your life is worth something’, and they felt sure that ‘it isn’t over yet’ if the doctor told them there were other treatment alternatives available.

Genuine presence

According to the informants in this study, the characteristics of a good consoler is being genuine and close. Being genuine was associated with being honest, being themselves, and wishing the person well. Family and friends who brought consolation were felt to be close if there was no need to hide anything or to embellish the truth.

It is clear from all informants that a genuine sense of being close is the premise that enables consolation to be forthcoming from fellow human beings. ‘Even serious information from the doctor is a source of comfort if the doctor cares’, said one of the women. The nurses who provided consolation were described as being genuine: ‘They are very honest. When they say something encouraging, it isn’t just to make it sound good; it is always right, and they mean it.’

The courage to acknowledge to their face that the informants were ill was part of what provided a sense of genuine presence. Some of the women talked about relationships that had become closer since they fell ill: ‘After I had said I was ill, some people’s presence became stronger. Others have pulled back, I think because they cannot handle the fact that I am dying.’

Being recognised

Being recognised refers to encounters with heathcare personnel. When the women were recognised, they received affirmation and acknowledgement. This gave them a sense of being meaningful – of having a worth beyond their disease. When the woman is acknowledged, her life is affirmed. In the hospital, the women felt comforted if the nurse or doctor recognised them.

One of the women expressed it in these terms: ‘They welcome me as a person rather than as a patient, more like a fellow human being. I am more than my disease.’ Another informant said that ‘I am not just a number on a list. And they are here to help me, specifically me’.

When they are recognised, they are being seen and welcomed, and someone takes responsibility for them. Healthcare personnel who recognised the informants provided reassurance that they were receiving the correct treatment and that they were being cared for. In the words of one of the women: ‘A year after I had the first operation, I feel it is the same staff I come across. They recognise me and show that they care and that they remember me. It gives me a feeling of being seen – which reassures me.’

Healthcare personnel showed that they recognised the women by using their first name, and by asking after family members and how things had been going since they last talked. In the words of the women, meeting healthcare personnel who recognised them, was like ‘meeting family and friends.’

Self-preservation

The women were acutely aware of the need to keep their spirits up, and they developed strategies to protect their own vulnerability. This involved avoiding support groups, being selective with whose company they accepted, and who they were spending time with when receiving chemotherapy. Listening to the pain suffered by other cancer patients was associated with increased existential distress.

In the words of one of the women: ‘I believe that being in the company of other people with cancer reminds you about the seriousness of the disease. Grappling with the seriousness is not always that good, things get too difficult – you may not even manage to get out of bed in the morning’. Several women pointed out that the suffering of other patients wore them down: ‘I am quite capable of seeing other people who are ill, but I know it doesn’t do me any good. This isn’t a bad dream I can wake up from – I am living it all the time.’

Although most of the women had not attended any support groups, they all shared the view that the groups were primarily discussing ‘death and misery’, which was expressed by one of the women in these terms: ‘It wears you down to be listening to other people talking about how ill they are.’ Meeting up with others suffering from the same disease was associated with concentrating on the disease rather than on life.

Discussion

The prognosis for women with recurrent ovarian cancer is poor, which leads to existential distress. In order to cope with their disease, the women find solace in the hope of recovery, seek consolation from other people who are genuine, and protect their own vulnerability by avoiding the company of other cancer patients. What can nurses do to console these women?

Is the hope of a future false?

Giving hope of a future provides consolation that relieves existential distress. A challenge arises from our findings. The women want honesty and genuineness; whatever is communicated must be true. If the consolation is not genuine, it provides no solace, according to Roxberg (17). This is echoed by the women in this study. Similarly, whatever provides solace must give hope of recovery and a longer life. If we look at prognoses and statistics, it is clear that the chances of recovery and a long life are poor.

The women who took part in this study were clear in their acknowledgement of the poor prognosis, but they hoped nevertheless to be among the few who would be able to live with the disease, whether thanks to a miracle, the trialing of new treatments, or luck. Nurses, doctors and others who might provide or believe in such hope, provided consolation. Earlier studies have shown that nurses shy away from giving hope, because they are familiar with the patient’s poor prognosis (4).

Is it acceptable to be raising hope of a future, even if it is highly likely to be false hope? Earlier studies show that women who are optimistic and are given much consolation live longer (11). Similarly, the women in this study found that suggestions they might have reason to be optimistic gave them strength, thus enabling them to engage with life. They felt comforted when healthcare personnel gave them hope by conveying prospects of a longer life and belief that they would respond to the treatment. This means that they cope by living their lives rather than by focusing on their illness. It should be added that all informants were fully aware of the seriousness of their disease.

Healthcare personnel who believe in the efficacy of the treatment, and who share the patient’s hope of a longer life, provide comfort. The finding matches earlier research showing that when healthcare personnel referred to the disease as a chronic disease, patients took an optimistic outlook, but when staff communicated that they expected the disease to recur, patients were more anxious (5). This tells us that awareness of their own communication processes will help healthcare personnel give patients hope of a longer life rather than a sense of having received a death sentence.

The nurse as a source of comfort

The hope of recovery was the women’s most powerful source of comfort, but from the point of view of healthcare personnel, showing that they recognise the patient is the consoling action that is easiest to implement in practice. All of the women who took part in the study communicated that they felt comforted by being recognised when they met with healthcare personnel, and it was not until they had become seriously ill that being recognised was so important.

From a perspective that sees existential distress focus on the fear of dying and questions about the meaning of life (8), is it really true that something as simple as recognising the patient can relieve their existential distress? The powerful impact of recognition on the women’s emotional lives may be associated with their sense of worth. Acknowledgment and affirmation of another person will convey an innate sense of respect for that person’s dignity, writes Kari Thorkildsen (18). The woman has a worth, and her life has meaning.

This also means that recognition overlaps the finding that hope of a future is associated with other people wishing the patient to live, and that other people feel they are of worth. Dignity therefore lies at the heart of solace. By recognising the informant, the nurse affords her dignity. This is consolation that relieves existential distress. But is it in everyone’s power to console?

The women who took part in the study clearly stated that those who wish to give solace, will need to be genuine and honest. They wanted to be comforted by people who believe in them, and who mean what they say (5). Løgstrup, a philosopher and theologist, says that when seeking to relieve someone else’s distress, truth is all-important. Honesty, for better or worse, is required. Without truth, the gift of the consoler will turn into flattery, which will be perceieved as fake (19).

Nurses are therefore in a position to provide consolation that is associated with conveying a sense of dignity rather than hope. The nurse who greets the woman as a whole person, as someone who exists beyond her diagnosis, will also give solace.

Support groups – consolation or threat?

Our study shows that friends who genuinely cared for the women became closer than they had been before the illness. This matches Arman and Rehnsfeldt’s (20) supposition that women seek more support from one another and therefore find themselves strengthened once the crisis is over. Support groups set up by healthcare personell are based on the idea that people in similar health situations may find soothing and supportive company in one another.

Hjulstad and Rannestad (6) found that women with recurrent ovarian cancer have a need to talk to others about their situation. However, our findings show that the women overtly avoid support groups because they fear having to engage with the seriousness of the disease, even if they have never attended any such group. Their fear can be seen as a strategy for coping with the disease, but the women may also miss out on consolation and support. This theme has implications for further research.

Methodology

The study design involving diary-keeping prior to individual interviews led to high-quality interviews. Although there were only five informants, the women’s reflections and interviews have provided great information richness. The women explained that they were able to tell their stories to the researcher, but not to the healthcare personnel. The chosen method has therefore meant that the women demonstrated trust in the researcher by talking openly about their sources of comfort.

Conclusion

The study shows that who you are as a nurse may determine whether a patient feels comforted or relieved of distress. Healthcare personnel can provide solace by recognising patients. Comforting words and actions will console only if the consoler is genuine and honest. The women themselves seek comfort in the hope of getting better. To protect themselves from the seriousness of the disease, the women will also avoid formalised support groups for other people, or specifically for women with cancer.

Implications for practice

In practice, it is a fact that cancer patients are surrounded by many different people at the hospital. Women with recurrent ovarian cancer need a good support network, including healthcare personnel in addition to family and friends. This can be facilitated by organising practice in a way that ensures that each cancer patient has a team of regular nurses and doctors around them. This will allow her to be recognised and feel comforted in that her existential distress is relieved. For women who have no close family or very few friends, the closeness of the healthcare personnell becomes even more important – because these women need fellow human beings who are there for them, and who acknowledge them.

Further studies should investigate how consolation may be incorporated into the nursing degree programme to make nurses better equipped to provide existential relief. Further studies should also investigate support networks for this group of patients.

References

1. Kreftregisteret. Nasjonalt kvalitetsregister for gynekologisk kreft. Årsrapport 2015. Available at: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/publikasjoner-og-rapporter/arsrapporter/publisert-2016/arsrapport-2015-gyneklogisk-kreft.pdf (downloaded 14.03.2017).

2. Szczesny W, Vistad I, Kaern J, Nakling J, Tropé C, Paulsen T. Impact of hospital type and treatment on long-term survival among patients with FIGO Stage IIIC epithelial ovarian cancer: follow-up through two recurrences and three treatment lines in search for predictors for survival. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37(3):305–11. PMID: 27352555

3. DellaRipa J, Conlon A, Lyon DE, Ameringer A, Kelly DL, Menzies V. Perceptions of distress in women with ovarian cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2015;42(3).

4. Howell D, Fitch M, Deane KA. Women’s experiences with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2003 februar;26(1):10–7.

5. Reb A. Transforming the death sentence: elements of hope in women with advanced ovarian cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 2007 november;34(6): s. E70–81.

6. Hjulstad H, Rannestad T. Har pasienter med tilbakefall av underlivskreft nytte av psykososial støttegruppe? Sykepleien Forskning. 2011;6(4):348–56. DOI: 10.4220/sykepleienf.2011.0186

7. Belcher SM, Sereika SM, Mattos MK, Hagan TL, Donovan HS. Comparison of symptoms and quality of life in recurrent ovarian cancer by rural/urban residence: Ancillary analysis of GOG-0259. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35:15_suppl, e18083-e18083. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e18083

8. Shinn E H, Taylor C L, Kilgore K, Valentine A, Bodurka D C, Kavanagh J, et al. Associations with worry about dying and hopelessness in ambulatory ovarian cancer patients. Palliation Support Care. 2009 september;7(3):299–306. DOI: 10.1017/S1478951509990228

9. Hwang K-H, Cho O-H, Yoo Y-S. Symptom clusters of ovarian cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, and their emotional status and quality of life. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2016;21(5):215–22. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.10.007

10. Vehling S, Malfitano C, Shnall J. A concept map of death-related anxieties in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2017;7(4):427–34. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001287

11. Lutgendorf S K, De Geest K, Bender D, Ahmed A, Goodheart MJ, Dahmoush L, et al. Social influences on clinical outcomes of patients with ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012 august 10;30(23):2885–90. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4411

12. Kreftforeningen. Smerte. Available at: https://kreftforeningen.no/rad-og-rettigheter/mestre-livet-med-kreft/smerte/ (downloaded 30.03.2017).

13. Kristoffersen NJ, Breievne G. Lidelse, håp og livsmot. In: Kristoffersen NJ, Nortvedt F og Skaug E-A, eds. Grunnleggende sykepleie. Bind 3. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag; 2007.

14. Eriksson K. Det lidende menneske. Copenhagen: Munksgaard Danmark; 2010.

15. Roxberg Å. Trøst. I: Gustin L, Bergblom I, eds. Vårdvetenskapliga begrepp i teori och praktik. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2012. s. 437–48.

16. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. 3. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2013.

17. Roxberg Å. Om tröst och att trösta. Michael (Tidsskrift for Det norske Medicinske Selskab). 2010;7(2):282–6. Available at: http://www.michaeljournal.no/asset/pdf/2010/2-282-6.pdf (downloaded 24.05.2017).

18. Thorkildsen KM. Kjærlighetens vesen i møte med lidelse. (Doktoravhandling.) Åbo: Åbo Akademi. Available at: https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/143901/thorkildsen_kari_marie.pdf?sequence=2 ;2017(downloaded 11.09.2017).

19. Løgstrup KE. Den etiske fordring. 4. ed. Århus: Forlaget Klim; 2012.

20. Arman M, Rehnsfeldt A. DEF: Det existentiella förbandet: existentiellt omhändertagande efter katastrof. Stockholm: Liber; 2012.

Comments