Where have all the nurses gone? A register-based analysis

Summary

Background: Almost 122,000 registered nurses are currently employed in Norway, but the demand for them is high and will increase in the future.

Objective: We aimed to investigate whether there is a group of nurses who can be recalled to patient-centred work. The findings can provide insight into the future potential for sustainability and preparedness in the health and care service.

Method: Using descriptive analyses of register data from Statistics Norway, we shed light on the current situation. We examine transitions to and from patient-centred nursing in the health and care industry in a short and longer time perspective.

Results: According to official statistics, 16% of registered nurses work outside the health service. The majority in the ‘Nurses’ category work in temporary employment agency activities. Many others hold positions relevant to nursing and work in education, research and public administration in central government and local authorities. Even though one in three nurses in patient-centred work hold part-time positions, many of them have more than one job, and on average, nurses work almost full-time overall (91%). The majority who leave patient-centred work move to positions with longer hours and/or no shift work, either in or outside the health service.

Conclusion: Our findings indicate that there is no large reserve of nurses. The vast majority hold relevant positions within nursing development, quality in the health service and patient safety, but without direct patient contact. Achieving the capacity increase proposed by Norway’s Health Personnel Commission could therefore be a challenge. The health statistics’ categorisation of where nurses work can thus give the false impression that many nurses are not utilising their education and expertise and that they represent a reserve that can be recalled to the health service. In order to safeguard the necessary supply, the focus on education and the import of nurses must continue, partly because a large proportion will soon reach an age where it is common to stop working.

Cite the article

Hjemås G, Syse A. Where have all the nurses gone? A register-based analysis. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(93304):e-93304. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.93304en

Introduction

There is currently a high demand for nurses in Norway (1). According to the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV), the number of vacant positions doubled from 2015 to 2023, from around 2350 to 4650 (2). The demand for nurses is expected to grow in the future, with Statistics Norway projecting an increase of 46,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs) by 2040 (3). This is primarily due to demographic changes in which Norway will experience significant population ageing in the coming decades (4).

Furthermore, both younger and older people are living longer with illnesses and conditions that require medical care. Norway’s Health Personnel Commission (1) emphasises the need for more nurses and highlights the major challenges of recruiting nurses in health and care services, particularly in primary care, but also in some specialist health services. Many nurses leave the profession because they are subject to the special age limit of 65 years, but many also leave because of health problems and receipt of health-related welfare benefits (1).

In an international perspective, Norway has a relatively high number of nurses and a low ratio of medical support personnel per capita (5, 6). This can partly be explained by the different methods that countries use to calculate the figures. Additionally, Norway’s expansive geographical area means that the demand for nurses is higher than in more densely populated countries. Approximately 4000 new nurses graduate in Norway every year, supplemented by around 1200–1400 nurses who are educated abroad (7).

The latter group mainly consists of immigrants, especially from other Nordic countries, but also a small percentage of Norwegians who have studied abroad. The number of nurses from outside Norway has remained relatively stable at around 5000 since 2018, as roughly the same number move to Norway as leave. Overall, nurses from other countries make up approximately 5% of nurses in Norway today.

This proportion has remained relatively stable over the past five years. The majority are from other Nordic countries (40%). Other large groups stem from the newest Eastern European members of the EU (20 per cent), followed by the Philippines, Germany and Australia.

In 2022, there were approximately 161,000 qualified nurses in Norway. Almost 122,000 of these were working, while 32,000 were pensioners. The rest were not part of the labour force for various reasons, such as studying, unemployment, starting a family or disability. However, not all qualified nurses work in the health service.

Objective of the study

In official statistics, a large number of nurses are categorised as working outside the health service. The objective of this article is to describe the factors contributing to the departure of employees from patient-centred nursing positions by showing the type of work these nurses are engaged in. We also describe their return to the health service.

Overall, the information presented in this article can give an indication of the reserve capacity in the Norwegian health service. A narrow and ‘patient-centric’ definition of the health service has been used in line with official documents and reports that examine the future need for nursing expertise (1, 3, 8, 9).

Method

Data sources

The data on education were retrieved from Norway’s National Education Database (NUDB) (10). The data on employment are from Statistics Norway’s annual register statistics on healthcare personnel (11), which is based on a-ordningen, a coordinated digital collection of information about employment circumstances, income and tax deductions for the working population living in Norway or abroad with a work affiliation to Norway in the form of financial benefits.

The register also includes all those with a health education who have a financial connection to Norway, whether working or not. We have extracted job and industry codes, occupation, FTE percentages, working time arrangements, number of jobs held and sector, as well as personal characteristics such as age, sex and immigrant background. The statistics are based on a reference week in November each year. For people with more than one job, it is the main job that is registered, whereby everyone is only counted once.

Variable definitions

Everyone who is a licensed or qualified nurse, either in Norway or abroad, is encompassed by our definition of nurse. The education codes (NUS2000) that are used are 661120 – Bachelor degree, nursing, three-year, and 661104 – College of Nursing, three-year foundation programme (12). We also include nurses who have gone on to qualify as midwives and public health nurses. Each of these groups constitutes 3–4% of all qualified nurses.

Our definition of the health service includes industries within the health and care service (industry codes 86, 87 and 88.1) (13). In the analysis, we have divided nurses into four primary categories based on a methodology that combines occupational (14) and industry codes (13):

- Practising nurses are identified by a combination of occupational codes (patient- and service user-centred) and industry codes (the health service), and correspond to the OECD’s definition of practising nurses in the health service (9, 15).

- Administrative nurses in the health service are nurses employed in the health and care service, but who primarily have occupational codes that correspond to administrative work.

- Nurses outside the health service are nurses who work in industries outside the health service. Most work in education and public administration. Some may also have jobs that seem patient- or service user-centred, for example in temporary employment agency activities.

- Nurses outside the labour force are either not registered as employed in the a-ordningen or are registered as self-employed. Older nurses often retire due to their age, while younger ones are outside the labour force for other reasons, such as care duties at home, studying, unemployment or disability.

Ethics

All data processing, including links and analyses, has been carried out in accordance with the Statistics Act (6). No further ethical approvals are required as we have not processed any health data.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics have been created for the number and proportion of nurses, FTE percentages and proportion of shift work overall and by age category (< 35, 35–44, 45–59, 60+ years) in and outside the health service in 2022. When exploring job transitions, we started with all nurses working in patient-centred roles in the health service in 2016 and examine the situation in 2022, six years later. In Appendix 1, we also present changes over a short time perspective, from 2021 to 2022, i.e. one year later.

We also show where nurses who leave patient-centred jobs in the health service end up in both a short and longer time perspective, one and six years, respectively. Thus, we examine both the influx to (from outside the health service and new graduates) and the outflux from the nursing profession to assess the total capacity. In the transition analyses, we have set the upper age limit to 55 in the year of departure to avoid including those who retired due to their age.

We examined whether personal characteristics such as age, sex, immigration background, country of education, level of education and centrality of place of residence influenced job transitions. There was only significant variation by age and, to some extent, sex, so these are the only characteristics presented here.

Results

Current situation

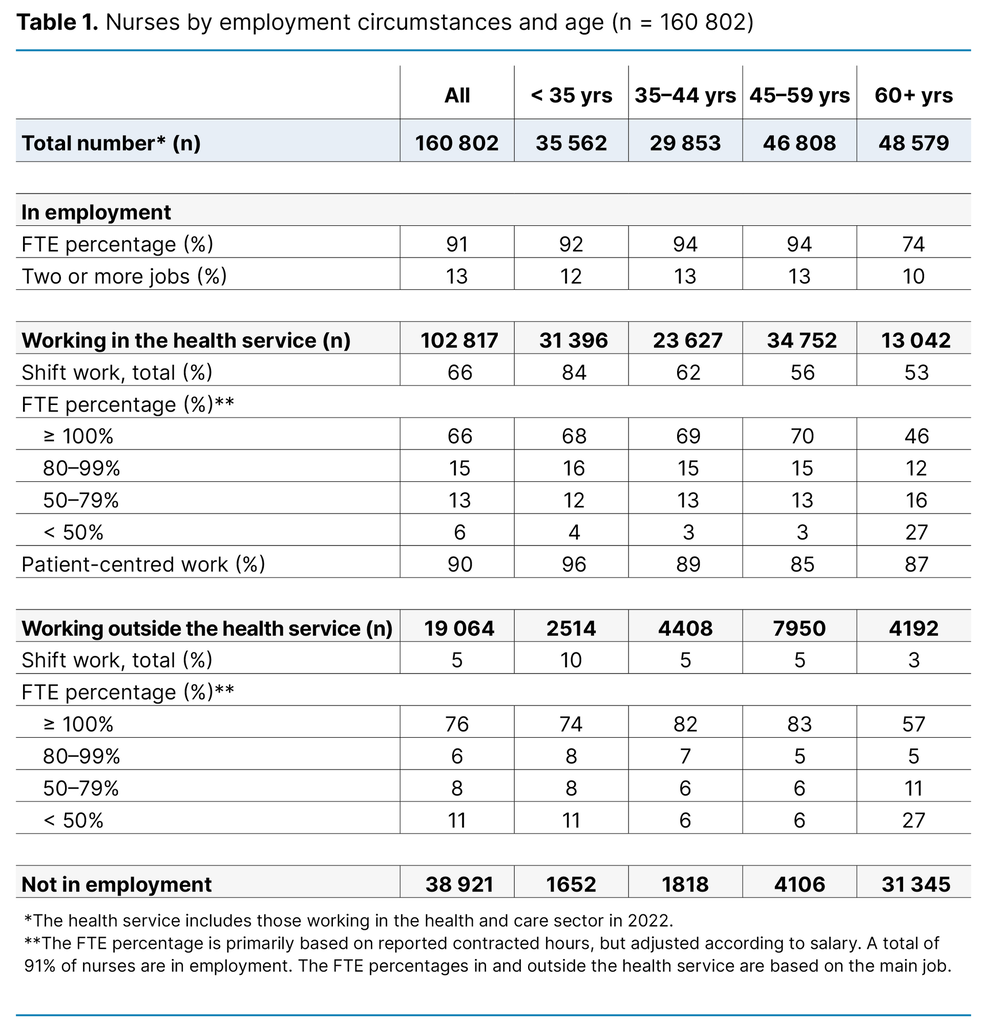

In 2022, there were 161,000 qualified nurses in Norway (Table 1). Of these, 38,921 are outside the labour force, and most are over the age of 70. The table shows that the majority of nurses in employment work in the health service – 80% of those below the age of 60.

The highest prevalence (88%) of nurses working in the health service is found in the youngest group (< 35 years), and the proportion decreases with increasing age. The proportion of those working outside the health service increases with age up to 59 years. The table also shows that younger nurses (< 45 years) tend to be in employment. The distribution by sex is not shown, but the men in employment (n = 13,287) are evenly distributed in the different age groups. However, a slightly higher percentage of male nurses (13%) work outside the health service than in it (9%).

Most of the nurses work almost full-time, with an average FTE of around 91%. However, the older nurses work slightly less. Among those in employment, the majority (87%) only have one job, and 88% of those with more than one job only have two jobs.

Overall, more than half (56%) of all nurses employed in and outside the health service worked shifts in 2022. This proportion decreases with increasing age – from 79% among the youngest nurses to 45% among the oldest.

In the health service, 9 out of 10 employees work directly with patients. The proportion is higher among the youngest nurses (96%) and decreases with increasing age (87% among the oldest nurses). The largest groups outside the health service work in education, public administration and social work activities without accommodation, such as kindergartens, out of hours school care etc. Most of the nurses who work in their profession outside the health service work in temporary employment agency activities.

FTE percentages are higher outside the health service than in it, with 76% and 66%, respectively, and are lower among the oldest nurses. The greatest difference is found in shift work: 66% in the health service work in such positions compared to just 5% outside the health service. The proportion of shift workers decreases significantly with increasing age across all health services.

According to background analyses, which are not presented here, the proportion working in the public sector is very high (85%). The analyses also show that the proportion is much higher among those working in the health service than outside it, with 92% and 49%, respectively. The proportion of nurses with a specialisation is somewhat higher in the health service (42%) than outside it (35%).

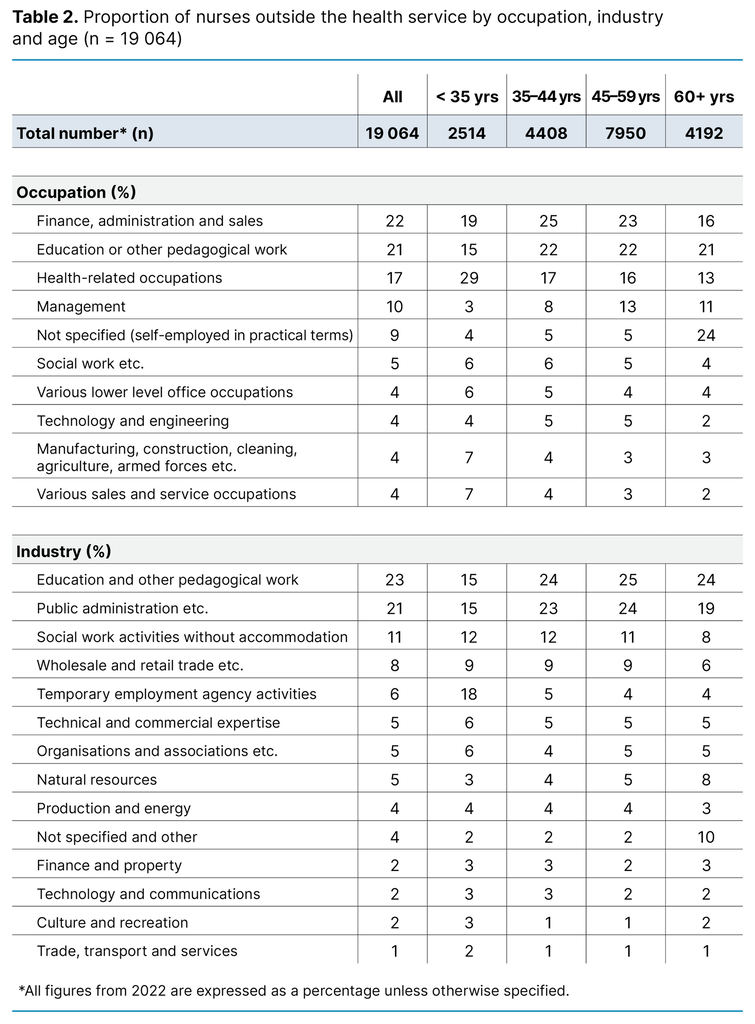

The vast majority of nurses working outside the health service are employed in finance, administration and sales (22%), or in education or other pedagogical work (21%) (Table 2). Among the youngest, almost one-third are employed in health-related occupations, and many of these work in temporary employment agency activities. It is likely that many of these, in practice, work as nurses in the health service.

In the age group 45–59 years, 13% are employed in management. In the oldest group (≥ 60 years), the largest proportion is self-employed (24%). There is considerable overlap between occupation and industry. By industry, the most common fields of employment are education (23%), followed by public administration (21%). The exception is observed among the youngest age group, where temporary employment agency activities is the most common industry.

To what extent do nurses leave patient-centred nursing?

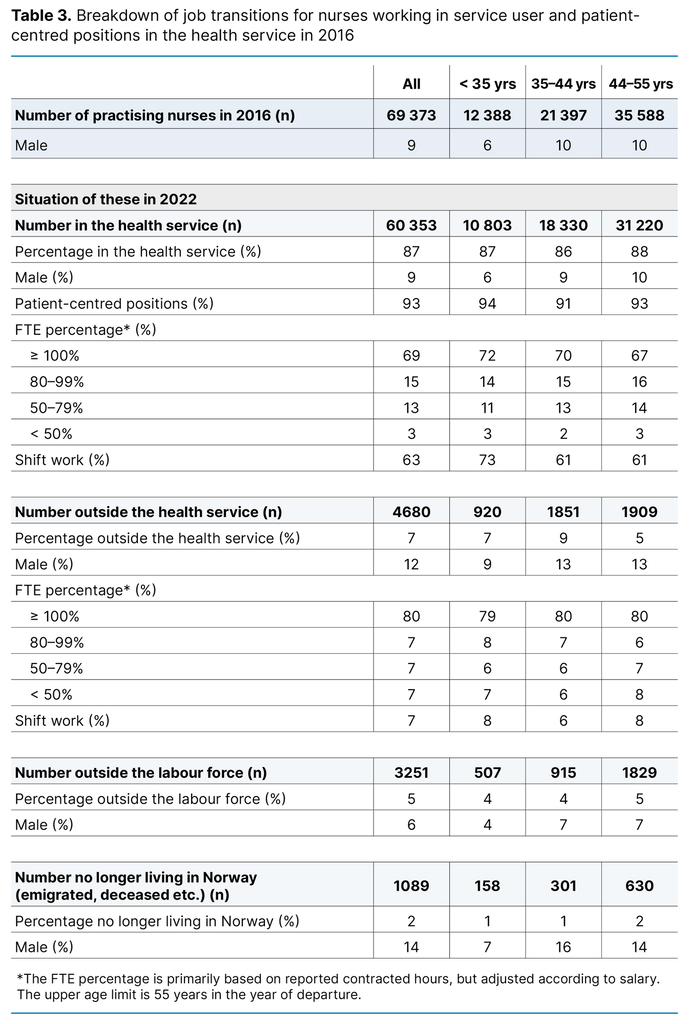

In the short period from 2021 to 2022, only 5% ceased to be practising nurses in the health service, see Appendix 1. Table 3 shows that the proportion is somewhat higher (13%) in the longer period from 2016 to 2022. Among those who remain in the health service, full-time and shift work are most common among the youngest age group and becomes less common with increasing age.

However, the difference between shift work in the health service and outside it is much more pronounced, at 63% and 7% per cent, respectively. For the proportion of these in full-time positions, the corresponding figures are 69% and 80%.

Where have all the nurses gone?

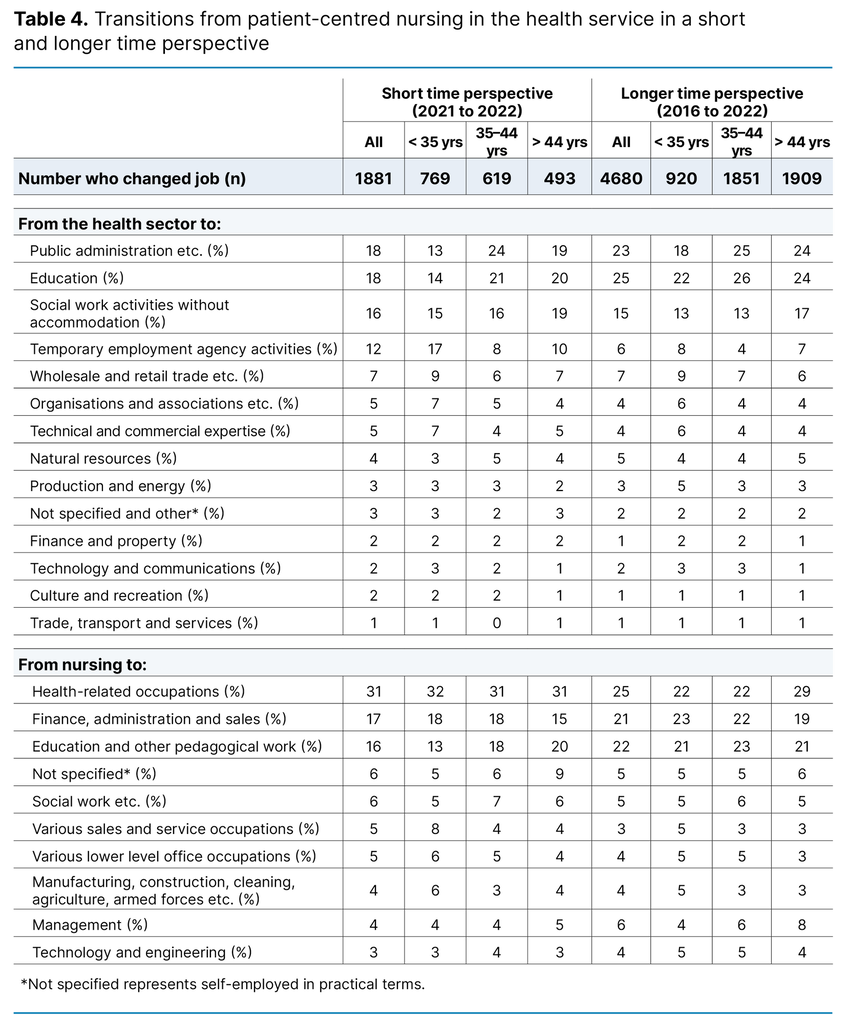

Table 4 shows which occupations and industries former practising nurses most often move to in a short and longer time perspective. The starting point is therefore practising nurses in 2021 and 2016 who, by 2022, have moved to a different field. The table shows that, in the short time perspective, most of the nurses move to public administration and education (both 18%), social work activities (16%) and temporary employment agency activities (12%). It is primarily the youngest nurses (under 35 years ) who switched to the latter group, while the older age groups moved to the first two groups.

Over a more extended period, the predominant industries remain largely consistent with those in the short time perspective. However, there is a slight increase in transitions to education (25%) and public administration (23%), accompanied by a decrease in transitions to temporary employment agency activities (6%).

In terms of occupation, the majority moved to health-related occupations, both in the short and longer time perspectives, with 31% and 25%, respectively. The age distribution is even in the short time perspective, while in the longer time perspective, moving to these occupations is more common among the oldest age group. Many also switched to finance, administration and sales, with 17% in the short time perspective and 21% in the longer time perspective, or to education or other pedagogical work, with 16% and 22%, respectively. There is not much variation by age, but in the short time perspective, relatively few of the youngest nurses transitioned to the education sector.

How many return to patient-centred nursing in the health service?

The majority of newly qualified nurses start their careers as practising nurses – 55% in the specialist health service and 37% in primary care (data not shown). This is also the case for those returning to the health service (Appendix 2).

A total of 45% entered the labour force, with a higher percentage observed among the youngest age group. It is possible that many of them continued onto further studies or took a break for other reasons. Many also returned from public administration (16%), social work activities without accommodation (9%), education and temporary employment agency activities (both 7%) (Appendix 2).

Most returned to a position with a higher FTE percentage than they had the preceding year, and many moved to a position with less shift work (data not shown). Appendix 3 shows that the majority returning from outside the labour force and outside the health service take up positions in primary care, with 59% and 65%, respectively. The proportion who moved to patient-centred work is higher among those from outside the labour force than from outside the health service, for both primary care and the specialist health service.

Discussion

Nine out of ten nurses in the health service work in patient-centred positions. Despite one in three having part-time positions, some have more than one job. This means that the potential to increase FTE percentages is already virtually exhausted within this group.

The largest groups who are categorised as working outside the health service work in education, public administration or temporary employment agency activities. We have shown that most nurses who change jobs or leave the profession move to positions with a higher FTE percentage or with no shift work. The latter is most common in roles with no direct patient contact. These motives can therefore partly explain their move away from patient-centred work.

In summary, the vast majority of nurses who are not categorised as working in patient-centred roles hold positions where their nursing education is either a prerequisite or is relevant to their duties. Although graduate level nursing education primarily focuses on clinical work, students learn a wide range of skills that are transferable to other fields: nurses’ experience from the health service may be relevant for jobs in public administration, particularly ones that are related to the health sector.

The same applies to nurses who are involved in the education of future healthcare workers. Our findings indicate that the proportion of nurses who work ‘unnecessarily’ outside the health and care service is relatively small, which is consistent with other countries (16). This is in line with the Health Personnel Commission, which concluded that nurses often find work in sectors where their specific skills continue to be beneficial to the health service (1).

What factors can impact on recruitment and staff turnover in the profession?

Various factors can influence a nurse’s decision to leave the profession (17, 18), defined as leaving patient-centred nursing in the health service. Our study cannot explain the reasons behind these career choices; however, two systematic reviews highlight personal characteristics, job demands, type of appointment, quality of the working environment and organisational culture as crucial elements in such decisions (17, 18).

The turnover rate of nurses is particularly high for those at an early stage of their career due to a combination of culture shock and heavy workloads (18). A Swedish survey examining why nurses leave the profession found that poor working conditions, unfavourable working hours, stress and heavy workloads were the most common reasons (16). In Norwegian studies of primary care, almost half of the nurses reported inadequate staffing levels and an excess of unqualified care workers in their workplace (19, 20).

The staffing situation directly impacts on nurses’ health at work and job satisfaction (20). This is supported by another Norwegian study, which identified these as two key factors in the decision-making process for nurses considering leaving their job, especially among the youngest age group (21).

In both Sweden and Norway, it has been concluded that services at risk of high turnover rates and/or that are seeking to encourage nurses to return to patient-centred roles can reverse the trend by ensuring a more manageable workload relative to working hours. They can also make it easier for nurses to avoid unwanted shifts and offer permanent jobs and full-time positions (16, 20).

To attract and retain as many nurses as possible in patient-centred services, the Health Personnel Commission recommends implementing measures that promote increased uptake and completion of a nursing education, enhance the quality of the education and clinical placements, and improve recognition of prior learning and work experience. These efforts will help to maximise the pool of people with the necessary qualifications to work as a nurse. Fewer details are given of the specific competencies that should ideally be included and at what levels they should be applied.

We have shown that the vast majority of qualified nurses are practising nurses, especially the youngest graduates. There does not therefore appear to be a problem in terms of the supply of nurses to the profession, but capacity challenges may arise in patient-centred services if a significant proportion does not remain in these roles over time. The precise point at which this becomes problematic is not clear, and the potential implications for other areas where nursing skills are needed are also not discussed (1).

According to the Health Personnel Commission, the capacity can also be increased if those currently working part-time in the health service are given more hours and a more favourable division of tasks (1). As mentioned above, our data suggest that the overall potential to increase the hours of part-time employees may already have been exhausted. However, a more favourable division of tasks could make it more appealing to remain and/or return to patient-centred work. Better opportunities for professional development, more interesting duties and favourable working hours can all help to enhance job satisfaction and competence. This could increase capacity by reducing sick leave and early departures from the profession (1).

Higher salaries are reported to be an important factor in studies that either examine risk factors for nurses leaving the profession (20) or their reasons for leaving patient-centred work (16). Norwegian trade unions and authorities also point out that higher salaries are important for both attracting and retaining staff (22). However, systematic reviews show that salary is not necessarily the decisive factor in retaining employees (17).

This could be because nurses are not guaranteed a higher salary outside the health sector in Norway (23). When they do receive a higher salary, it is partly due to the fact that the average age – and thus competence and length of service – of these nurses is higher (24). The exception here is within temporary employment agency activities, where the average age of nurses is lower, but the salary is higher than in the health and care services (24). Therefore, it is not only age that impacts on differences in pay, and this needs to be investigated further.

The Health Personnel Commission cautions against the belief that Norway can solve the future challenges in the health and care sector by importing labour. On the one hand, it points out that a conscious focus on importing labour will make the health service more vulnerable because foreign healthcare personnel are more mobile. Meanwhile, imported labour may be unsupportive towards other countries that also have a demand for their labour. However, the commission notes that a continued influx of doctors and nurses from abroad will be necessary (25).

In our view, it is uncertain whether Norway will be able to attract a sufficient number of migrant workers in the coming decades to increase the supply of well-qualified health care staff. Ageing and the demand for labour are not uniquely Norwegian phenomena (25). It is conceivable that traditional labour-export countries may make it more attractive for nurses to work in their own country, while Norway faces strong competition for this type of labour from other countries with a less protectionist approach to ‘brain drain’ (26, 27).

Does staff turnover in the nursing profession differ from that of other professions?

Nursing is predominantly a female profession in the public sector, as is teaching in primary and lower secondary schools. A report comparing graduates from these professions in 2005 and 2015 found no significant difference in the turnover rates (23). Many also start their careers working for employment agencies but move to the public sector after a period of time. A key finding is that the number who remain in the health service three years after completing their education has actually increased over time (23).

Another reason why nurses leave the health service, which is not addressed here, is health-related absenteeism. According to NAV, sick leave rates are particularly high in the health service, especially for nurses (28). According to Statistics Norway, this type of absenteeism increases with age (29). Adequate capacity is vital in the health service going forward, and the Health Personnel Commission therefore recommends measures to improve older nurses’ health at work as well as strategies to postpone their retirement (1).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study has many strengths. It is based on register data and thus includes the entire population of nurses in Norway. We examine both cross-sectional and longitudinal perspectives with changes in a short and longer time perspective. The register data enabled us to prospectively record information on many different characteristics of individuals and their employment circumstances. However, this data does not provide insight into why people make the choices they do.

Another weakness was the lack of opportunity to examine earned income in this study. The extent to which salary plays a role in the choice of workplace and position should be further examined. There are also some challenges related to errors and/or omissions in our register data, particularly in relation to undisclosed occupations and/or industries. Some of these people are likely to be sole proprietors engaged in patient-centred roles, but it was not possible to clarify this.

It is likely that temporary employment agency activities encompass many who are employed as nurses in the health sector, but whom we are unable to identify as practising nurses because we do not know if they work in patient-centred care or more administrative roles. Furthermore, there are most likely some misclassifications of occupations in certain organisations. It is unlikely that such a large proportion work as a ‘nurse’ in industries outside the health service as indicated in the register data from Statistics Norway and similar institutions.

Finally, our age limit parameters mean that we have not examined job changes among the oldest group of nurses in employment. This is because we wanted to look at staff departures to/from other organisations as opposed to exits from the labour force. A relatively large proportion of the oldest nurses will likely have retired due to age or disability. Nevertheless, the overall figures are relatively clear, and the findings are consistent. The weaknesses in the main conclusions are therefore not considered significant.

However, to further understand why nurses make the career choices they do, further studies using different data and methodologies are required. This would give both the authorities and the Norwegian Nurses Organisation a more realistic picture of the future potential for sustainability and preparedness in nursing in Norway.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that Norway’s nursing capacity is currently being well utilised, and that there is no large reserve of nurses. Most of those who appear to have left the profession work in relevant positions that contribute to professional development, quality in the health service and patient safety, but without direct patient contact. It may therefore be difficult to achieve the capacity increase set out in the Health Personnel Commission’s report.

Could the current categorisation of where nurses work give the false impression that many nurses are not utilising their education and expertise and that they represent a reserve that can be recalled to patient-centred positions in the health and care service? In order to ensure the necessary supply of nurses, a continued focus on education and the import of nurses will be crucial, partly because a large proportion will soon reach an age where it is common to stop working.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Correction in table 2:

Total number, All, has been corrected from 19 to 19 064.

Comments