Changes in nursing homes and home-based nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic

RNs in the primary healthcare service showed that they can be highly adaptable in a crisis. Preparedness, infection control plans and support in their daily work were critical to how well they dealt with the pandemic.

Background: Registered nurses’ (RNs’) ability to change and adapt was put to the test when Norway and the rest of the world were plunged into the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Strict infection control rules were introduced, and the main focus in primary healthcare services was infection control and prevention. Since RNs are one of the largest groups of healthcare personnel, their efforts were critical for the successful management of the pandemic. The pandemic also led to various changes to their work tasks, responsibilities and working environment.

Objective: The purpose of the study was to explore RNs’ experiences with adaptation in nursing homes and home-based nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method: We used a qualitative design consisting of two group interviews with a total of ten RNs in nursing homes and home-based nursing care. Both group interviews were conducted in a relatively small municipality in December 2020 and February 2021 during the pandemic. The data analysis is based on Malterud’s systematic text condensation method.

Results: The findings of the study highlight the scope of RNs’ responsibilities and function during a pandemic, and can be divided into three main themes: 1) Being in a constant state of pandemic preparedness, 2) RNs’ perceptions of the special responsibility they had for preventing infection, and 3) A need for structure and information in their daily work. The RNs showed that they had the capacity and willingness to adapt, and took on more responsibility during the pandemic. However, they were dependent on structure, support and receipt of sufficient information in their daily work.

Conclusion: The study shows that the RNs in the primary healthcare service had the capacity to be highly adaptable during the pandemic, and had a willingness to adapt and a sense of duty. However, good pandemic preparedness procedures, up-to-date infection control regulations and support from colleagues and management are crucial to managing the pandemic, particularly due to the protracted nature of the situation. Knowledge of the RNs’ experiences can be helpful in the planning and organisation of preparedness for future crises, where nurses play a key role in the successful management of the situation.

RNs’ ability to change and adapt was put to the test when Norway and the rest of the world were plunged into the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (1). Overnight, the pandemic and infection control became the top priority in the health service when Norway went into lockdown on 12 March 2020. The pandemic led to changes in the duties, responsibilities and working hours of nurses throughout the world. The lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and uncertainty about its correct use contributed to the sense of unease (2–5).

The efforts of RNs – as one of the largest groups of healthcare personnel – were an important factor in the successful management of the pandemic. In 2020, the research on nurses and COVID-19 mainly stemmed from Asia and the United States.

Most of the studies focused on nurses ‘on the frontline’, i.e. those working in intensive care units or other wards with COVID-19 patients. The studies show that the function and area of responsibility of this group of nurses make them vulnerable to the psychological after-effects of the pandemic. There is a considerable need for guidance, and clear concern about infecting others. The studies also highlighted the importance of robust, professional management as well as sufficient supplies of PPE and personnel (4, 6–9).

Research from Wuhan in China also points to the major psychological strain nurses faced in the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (10). Another study from Australia reports that the psychological strains have led to many nurses considering leaving the profession (11).

In Norway, few studies have been published of RNs in the primary healthcare service in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. In October 2020, the research organisation SINTEF published a study, commissioned by the Norwegian Nurses Organisation (NNO), of Norwegian RNs’ experiences in the initial stages of the pandemic (1).

In a national survey, SINTEF sent questionnaires to all NNO members. Over 35 000 responded, and a further 35 nurses were interviewed. Findings from the survey show that during the pandemic, RNs had longer working hours and different duties, and worked in different places. They also experienced higher workloads and reduced job satisfaction.

Kirkevold et al. (12) conducted studies on infection control in Norwegian nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. They identified challenges related to the reuse of PPE, difficulties in maintaining the recommended distance from patients, and inconsistent procedures for training staff in infection control.

Much of the research on RNs and COVID-19 in 2020 focussed on the specialist health service. More research was therefore needed in the primary healthcare service on the RNs experiences and perceptions in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective of the study

The purpose of the study was to explore RNs’ experiences with adaptation in nursing homes and home-based nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic. We investigated how the pandemic affected the RNs’ new working day and their handling of procedures and duties.

Method

The study is based on group interviews aimed at eliciting RNs’ viewpoints and experiences as an employee in the primary healthcare service during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of the group interviews was to foster discussion and reflection (13) and to develop knowledge about RNs’ collective attitudes to and experiences with the changes to their work during the pandemic (14).

Sample and interviews

Two group interviews were conducted in a municipality in southwestern Norway with a population of less than 5000. Six participants took part in the first interview, which was held in December 2020, and four participants took part in the second interview, in February 2021.

The aim was to recruit participants from several municipalities, but the strict infection control measures in the nursing homes prevented us from conducting interviews at more frequent intervals or in other municipalities.

The participants represent a strategic sample of RNs with varied backgrounds in terms of work experience, age (13, 15) and place of work. The first author sent out a written invitation and information to a total of 15 RNs, which is an appropriate size for a qualitative sample (16).

Ten of the RNs were able to participate in the interviews. We held a second interview to explore the findings in more depth and to achieve data saturation. The interviews were held in premises close to the nursing home and lasted for 90 and 75 minutes respectively. The first author conducted the interviews and used a semi-structured interview guide as a starting point.

Our interview guide was based on previous studies and the first author’s work experience in the primary healthcare service in the early stages of the pandemic. The interview guide was not followed chronologically, but it served as a starting point for conversation. We asked the participants questions about their experiences during the pandemic and the changes to their infection control procedures and expertise.

We recorded the interviews on audiotape and took written notes. The first author is a specialist nurse who works in patient-centred nursing and the professional development of nursing in the same municipality as the participants, and has regular contact with the participants at work.

Analysis

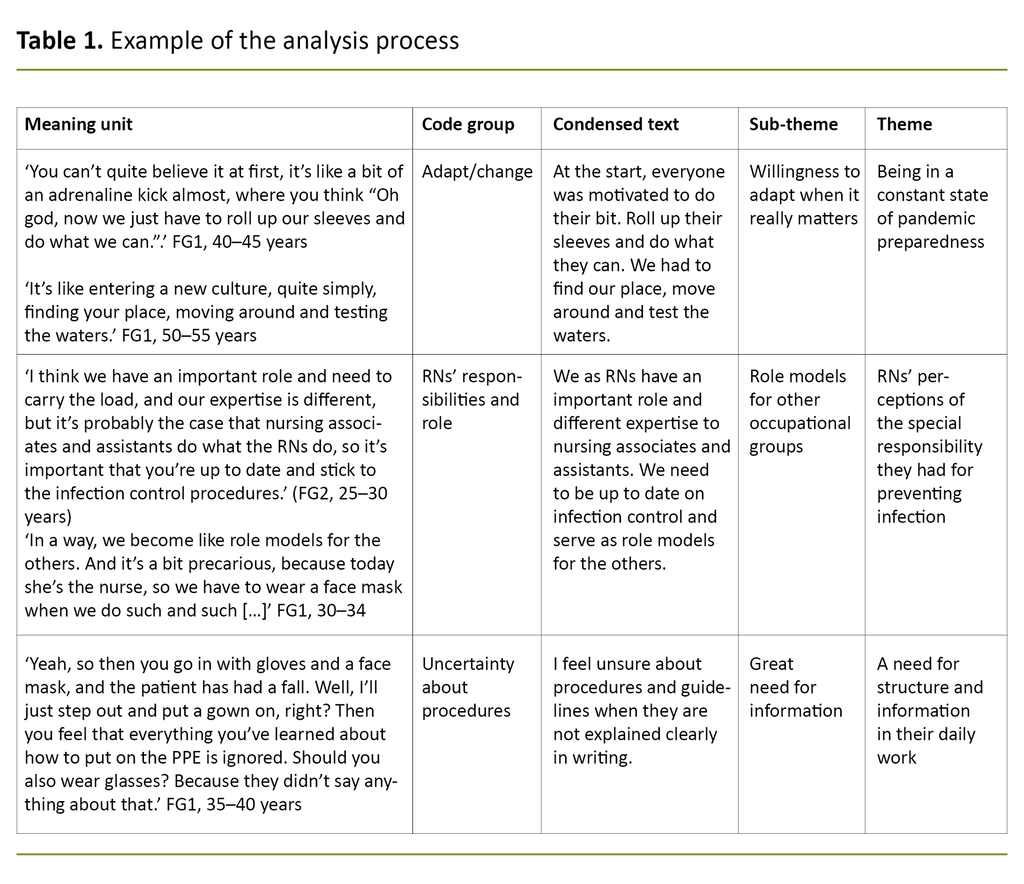

The analysis of the group interviews is based on Malterud’s systematic text condensation method (17), which we performed in four steps (see Table 1). We read the transcribed data material to form an overall impression and then formulated preliminary themes. The meaning units were then sorted into groups and coded, and this formed a starting point for condensation. The condensed text formed the basis for themes and sub-themes.

When analysing the transcribed material, we paid special attention to the fact that the first author knew several of the participants and that this could potentially impact on how questions were asked and how the themes unfolded. To create the necessary distance to the material, the first author noted her understanding of the situation at the participants’ workplace prior to the interviews.

She also conducted a literature review in the field and discussed the coding of the material and development of themes with the second author. To ensure the reliability of the findings, we discussed any discrepancies or alternative interpretations until we reached a consensus.

Ethics

The Norwegian Centre for Research Data, reference number 919371, approved the study and granted permission to collect data in the two municipal institutions. Participants received written information about the study and signed a consent form indicating their right not to take part or to withdraw at a later date.

Participants were deidentified in the transcript and further anonymised in the presented results. When referring to the participants’ quotes, we use the term ‘focus group interview participant’ (FG) followed by a corresponding number.

Results

The ten participants in the study were women aged 26 to 55 years, with an average of 14 years’ experience as RNs. Six of the participants worked in nursing homes and four were in home-based nursing care. The main findings of the study can be divided into three themes: 1) Being in a constant state of pandemic preparedness, 2) RNs’ perceptions of the special responsibility they had for preventing infection, and 3) A need for structure and information in their daily work.

Being in a constant state of pandemic preparedness

When the pandemic began and Norway went into lockdown, the RNs’ working situation changed dramatically. The initial rationing of scarce PPE and the separation of staff in home-based nursing care from staff in nursing homes were in stark contrast to the extensive collaboration between the two groups of workers before the pandemic.

Frequent changes in guidelines and working for one to two weeks without a break caused disquiet among the RNs. However, because of the severity of the situation, the RNs wanted to do what they could to help.

Several nurses used terms such as ‘rolling up your sleeves’ and ‘getting stuck in’ when describing their experiences in the first lockdown. They told how they wanted to do their best to provide a good service, but found the reduced care provision for older patients as the most vulnerable group, and the need to keep them socially distanced from other people to be particularly challenging.

Most felt that they were in a constant state of pandemic preparedness in anticipation of a possible outbreak.

Several of the nurses described how they felt unsure about dealing with infections and infection control procedures. Most felt that they were in a constant state of pandemic preparedness in anticipation of a possible outbreak. One participant said: ‘When we first heard about the corona virus, our municipality didn’t have any cases. And we haven’t had that many. But having to constantly think about and prepare ourselves in case something did happen. Yeah, we had to constantly be braced for an infection outbreak’ (FG1, 40–45 years).

During the course of the pandemic, most of the RNs’ working hours stabilised. The separation of the services remained in place, and the RNs became used to the new ways of working. They learned to live with the uncertainty in their daily work and deal with their constant state of preparedness. The social distancing and general infection control procedures became part of their working day, and the RNs reflected on how quickly they adapted.

RNs’ perceptions of the special responsibility they had for preventing infection

The participants believed that their function as nurses had an impact on how infection control was managed at their workplace, especially in the evenings and at weekends when they were often the only RN on duty.

Several participants said that they had more responsibility than usual during the pandemic, and one RN’s handling of procedures in the evenings and at weekends was considered to apply to all staff. They also described how other staff expected the RNs to have control of and knowledge of most pandemic-related issues.

The RNs tended to have responsibility for the patients who needed to be isolated, and had to ensure that others followed the procedures. Some participants found this responsibility a burden, particularly those who were unsure about the guidelines and procedures. Others found the documentation they needed at their workplace and also asked the other staff to read this.

Several described how they were afraid of being infected and passing on the infection to colleagues and patients.

Most of the participants felt that as nurses they also had a responsibility in their personal lives. Several described how they were afraid of being infected and passing on the infection to colleagues and patients. The nurses did not want to be accused of doing anything that was contrary to the recommendations and that could result in infection outbreaks or deaths. They were aware of the importance of their function as a nurse in society.

One participant described it as follows: ‘It’s like an extra thing to worry about, because I feel that I have to stay healthy. So it’s been at the expense of everything else, I’ve kept myself to myself and haven’t travelled anywhere. You drop all social contact so that you can stay healthy and go to work and not infect your patients’ (FG1, 45–50 years).

Support from colleagues was shown to be crucial for the nurses being able to cope with the responsibility they had during the pandemic. Several indicated that the best support they received was from each other, and that there was a ‘phone a friend culture’ in the workplace. They described how they would not hesitate to contact each other when they were unsure about something.

Most understood that the staffing level was precarious after separate groups were formed and kept apart in order to reduce the risk of infection. They felt a great sense of responsibility not to burden colleagues with their own absence.

A need for structure and information in their daily work

In order for the nurses to feel reassured and have a sense of control, it was important that amended and new guidelines were issued and accessible. The participants told how the flow of information varied, as reflected in the following quote: ‘There’s a lot of information to read, and it’s difficult to keep track of it all. Some relates to the patients, some their families, some has been sent in a text message, then there are procedures for the emergency team, a memo for those in home-based nursing care. There are lots of different bits of information to relate to’ (FG1, 35–40 years).

Many of the nurses said they found it challenging that other occupational groups did not always receive information about amended procedures. Consequently, the participants felt an extra responsibility for ensuring that both themselves and their colleagues followed the infection control procedures. The procedures for visitors were constantly being changed and were difficult to keep up with. Where the guidelines seemed ambiguous, it was up to the RN to decide what to do.

The RNs raised the issue of having to use their discretion in applying the guidelines, as everyone interpreted them differently. This challenge was also exemplified by their uncertainty about, for example, the use of PPE in the personal care of patients, assessing social distances and the definition of close contact.

The rationing of PPE at the start of the pandemic and the feeling of uncertainty when dealing with patients with suspected COVID-19 were also examples of situations where the RNs had a particular need for support and information in order to feel reassured.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to explore RNs’ experiences with adaptation in nursing homes and home-based nursing care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main findings show that although RNs as a professional group have wide-ranging experience with change and adaptation, the pandemic gave them the sense of being in a constant state of pandemic preparedness and strengthened their willingness to adapt and sense of duty.

The findings show that the RNs have the capacity to be highly adaptable in a crisis, but that preparedness, infection control plans, receipt of sufficient information and support from managers and colleagues were vital to their handling of the crisis.

RNs’ capacity in a crisis

The findings show that the RNs were willing to adapt quickly in terms of working hours, workplace and taking on additional work tasks. The description of ‘rolling up your sleeves’ corresponds well with the general attitude of RNs in Norway at the start of the pandemic, as reported by SINTEF (1).

The survey showed that, in Norway, around one-third of RNs’ working hours changed due to the pandemic. Although the pandemic brought about a major upheaval in everyday working arrangements, the RNs in our study seem to have accepted and understood the changes and the uncertainty that this has entailed. Research on the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in 2009 also shows that nurses are more willing to accept changes to working hours and a greater workload in a crisis situation (18).

Access to PPE when needed, as well as adequate training and practice are necessary for RNs being able to deal with the situation. These factors have also been crucial for healthcare personnel’s feeling of reassurance in comparable situations, such as during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone in 2015 (19). At that time, PPE supplies were better, which meant that patients and healthcare personnel were significantly safer than in previous outbreaks in, for example, Uganda (20).

However, our study shows that such a radical change in working conditions over a long period can also give RNs the sense of being in a constant state of pandemic preparedness in anticipation and fear of a possible outbreak in the workplace.

In recent years, the work of RNs in the primary healthcare service has changed and expanded as greater numbers and more seriously ill patients have been discharged from the specialist health service (21, 22). The hospitals’ prioritising of beds for COVID-19 patients has also increased the number of tasks transferred to the primary healthcare service during the pandemic (23).

The pandemic has put additional pressure on RNs in their daily work and their capacity to practise good nursing care.

This means that local authorities are now having to provide more health services to the sickest and most vulnerable patients. Our findings can be viewed in light of the changes that have characterised the primary healthcare service in recent years, where RNs are continuously having to adapt to changes whilst providing a good health service for patients (24). It is therefore clear that the pandemic has put additional pressure on RNs in their daily work and their capacity to practise good nursing care.

As a professional group, the RNs took responsibility for preventing the spread of infection in the workplace and felt like role models for other employees. There was an expectation that the RNs would be in control of and manage infection control and procedures.

As the largest group of healthcare professionals, RNs have gained global recognition and played a key role in the pandemic (25, 26), and their expertise in infection prevention, critical care, palliative care and public health is of vital importance to the care that patients receive (25).

RNs’ adaptability and crucial expertise in health care may therefore have contributed to them naturally assuming professional authority and responsibility during the pandemic.

Need for follow-up over time

During the pandemic, the RNs were given extra responsibility, especially on shifts where no other RNs or managers were present. This meant that they automatically assumed a leader role towards their colleagues. When they felt out of their depth with this responsibility, peer support from other RNs played an important role in their handling of the task.

Previous studies also show the importance of a supportive working environment and team spirit for sharing experiences and knowledge among RNs (27, 28), not least to motivate them in their handling of crisis situations (29).

In order to feel reassured, the RNs were dependent on understanding the various guidelines and procedures.

In the interviews, it was clear that receipt of useful and sufficient information was important. In order to feel reassured, the RNs were dependent on understanding the various guidelines and procedures. Findings from international studies on the COVID-19 pandemic and other pandemics show that management support is important in this context for RNs to feel a sense of control (2, 3, 18–20).

Kirkevold et al. (12) also make the point that leaving it to individual employees to figure out the infection control procedures was not very practical, and that compulsory training was necessary. Other studies show that staff feel more reassured when managers have a strong presence ‘in the field’ in crisis situations (30, 31).

In our study, this proved particularly relevant when there were no other RNs or managers present, where the RN on duty had to take sole responsibility for managing infection control.

A Canadian study shows that after the outbreak of SARS in 2003, healthcare personnel experienced long-term negative effects such as burnout (32). The most surprising finding of the study was that the consequences primarily affected healthcare personnel who did not work closely with infected patients. One possible explanation for this is that healthcare personnel who are specially trained to work in intensive care have more knowledge and experience of similar situations (32).

Our findings show that garnering experiences from previous pandemics and outbreaks will help institutional management identify and prevent the negative effects of the pandemic in the primary healthcare service. Active use of experienced RNs to support less experienced staff is an important measure in this context (31, 32).

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly tested the resolve of nurses in the primary healthcare service. Their willingness to adapt and their sense of duty are probably related to their position as frontline healthcare personnel, with wide-ranging responsibilities and functions, but also with close patient contact (24).

The RNs have shown that they have the capacity for radical change, but that they are vulnerable to the effects of being in a state of preparedness over a long period of time. However, good preparedness procedures, updated guidelines for infection control management, a strong presence by managers and support from colleagues can be crucial to preventing undesirable long-term effects from the pandemic.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The first author conducted the group interviews in her own municipality and knew several of the participants. It was therefore a strength of the study that the participants felt secure and shared information that would have been difficult for an external researcher to obtain.

It may be a weakness that the author had limited distance to the participants' experiences, and potentially overestimated the RNs’ challenges during the pandemic. However, the data analysis process was conducted together with the second author, who had no connection to the reference municipality. This limited the potential for bias in the interpretation of the data.

The study was conducted in a relatively small municipality with a small community of healthcare professionals, which could limit the transfer value of the results to larger municipalities. However, small municipalities must be able to handle outbreaks and provide health services in the same way as larger municipalities, and the findings about RNs’ experiences in a small municipality concur with a national survey of RNs in the early stages of the pandemic (1).

Group interviews fostered discussion and reflection in the group. However, in-depth interviews, potentially in combination with observation, could have provided more comprehensive data and a broader understanding of the behaviour and culture in the workplace.

Conclusion

The study showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, RNs in the primary healthcare service had the capacity to be highly adaptable. Their willingness to adapt and sense of duty enabled them to take on extra responsibilities as a result of their position as frontline healthcare personnel. The study also showed that being in a state of preparedness over a long period has been challenging for the RNs, who were concerned that they should not pose a risk to vulnerable patients.

The need for information and structure increased in pace with the changes and highlighted the importance of updating infection control guidelines and regulations and ensuring they are accessible. In order to be able to properly deal with the extra responsibility, the RNs needed considerable support from colleagues and managers.

Knowledge of the RNs’ experiences can be helpful in the planning and organisation of preparedness for future crises, where nurses play a key role in the successful management of the situation.

References

1. Melby L, Thaulow K, Lassemo E, Ose SO, Sintef. Sykepleieres erfaringer med første fase av koronapandemien. Oslo: Norsk Sykepleierforbund; 2020. Project no. 102023284. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/sites/default/files/inline-images/sKH8UPyCeoJa8acd5TKYOFcqykeFgXtDdIsNr6yPSsikR17Nls.PDF (downloaded 03.03.2022).

2. Halcomb E, McInnes S, Williams A, Ashley C, James S, Fernandez R, et al. The experiences of primary healthcare nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: COVID-19 in Australian PHC. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2020;52:5:553–63. DOI: 10.1111/jnu.12589

3. Halcomb E, Williams A, Ashley C, McInnes S, Stephen C, Calma K, et al. The support needs of Australian primary health care nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(7):1553–60. DOI: 10.1111/jonm.13108

4. Yi X, Jamil NB, Gaik ITC, Fee LS. Community nursing services during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Singapore experience. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2020;25(8):390–5. DOI: 10.12968/bjcn.2020.25.8.390

5. Specht K, Primdahl J, Jensen HI, Elkjær M, Hoffmann E, Boye LK, et al. Frontline nurses' experiences of working in a COVID-19 ward – a qualitative study. Nursing Open. 2021;8(6). DOI: 10.1002/nop2.1013

6. Labrague LJ, Santos JAA. COVID‐19 anxiety among front‐line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(7):1653–61. DOI: doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121

7. Shahrour G, Dardas LA. Acute stress disorder, coping self‐efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID‐19. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(7):1686–95. DOI: 10.1111/jonm.13124

8. Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;13(1):1–8. DOI: 10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5

9. Xu H, Intrator O, Bowblis JR. Shortages of staff in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: What are the driving factors? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020;21(10):1371–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.002

10. Leng M, Wei L, Shi X, Cao G, Wei Y, Xu H, et al. Mental distress and influencing factors in nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. Nursing in Critical Care. 2021;26(2):94–101. DOI: 10.1111/nicc.12528

11. Ashley C, James S, Williams A, Calma K, Mcinnes S, Mursa R, et al. The psychological well-being of primary healthcare nurses during COVID-19: a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2021;77(9):3820–8. DOI: 10.1111/jan.14937

12. Kirkevold Ø, Eriksen S, Lichtwarck B, Selbæk G. Smittevern på sykehjem under covid-19-pandemien. Sykepleien Forskning. 2020;15(81554):e-81554. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2020.81554

13. Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2012.

14. Johannesen A, Tufte PA, Christoffersen L. Introduksjon til samfunnsvitenskapelig metode. Oslo: Abstract forlag; 2016.

15. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

16. Kvale S, Brinkmann S, Anderssen TM, Rygge J. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3rd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

17. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

18. Honey M, Wang WYQ. New Zealand nurses perceptions of caring for patients with influenza A (H1N1). Nurs Crit Care. 2013;18(2):63–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00520.x

19. Andertun S, Hörnsten Å, Hajdarevic S. Ebola virus disease: caring for patients in Sierra Leone – a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(3):643–52. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13167

20. Locsin RC, Matua AG. The lived experience of waiting‐to‐know: ebola at Mbarara, Uganda – hoping for life, anticipating death. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37(2):173–81. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02069.x

21. St.meld. nr. 47 (2008–2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2009.

22. Killie PA, Debesay J. Sykepleieres erfaringer med samhandlingsreformen ved korttidsavdelinger på sykehjem. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning. 2016;12(2). DOI: 10.7557/14.4052

23. Førde R, Magelssen M, Heggestad AKT, Pedersen R. Prioriteringsutfordringer i helse- og omsorgstjenesten i kommunene under covid-19-pandemien. Tidsskrift for omsorgsforskning. 2020;6(1):1–4. DOI: 10.18261/issn.2387-5984-2020-01-11

24. Debesay J, Harsløf I, Rechel B, Vike H. Dispensing emotions: Norwegian community nurses' handling of diversity in a changing organizational context. Soc Sci Med. 2014;119:74–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.025

25. Schwerdtle PN, Connell CJ, Lee S, Plummer V, Russo PL, Endacott R, et al. Nurse expertise: a critical resource in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86(1):49. DOI: 10.5334/aogh.2898

26. Verdens helseorganisasjon (WHO). Nurses and midwives critical for infection prevention and control. WHO; 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UHL-HIS-2020.6 (downloaded 03.03.2022).

27. Abraham CM, Zheng K, Norful AA, Ghaffari A, Liu J, Poghosyan L. Primary care practice environment and burnout among nurse practitioners. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2021;17(2):157–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.11.009

28. Røkholt G, Davidsen L-S, Johnsen HN, Hilli Y. Helsepersonells erfaringer med å implementere kunnskapsbasert praksis på et sykehus i Norge. Nordisk sygeplejeforskning. 2017;7(3):195–208. DOI: 10.18261/issn.1892-2686-2017-03-03

29. Villar RC, Nashwan AJ, Mathew RG, Mohamed AS, Munirathinam S, Abujaber AA, et al. The lived experiences of frontline nurses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Qatar: a qualitative study. Nursing Open. 2021;8(6):3516–26. DOI: 10.1002/nop2.901

30. Poortaghi S, Shahmari M, Ghobadi A. Exploring nursing managers' perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID-19: a content analysis study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(27):2021. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-021-00546-x

31. Maben J, Bridges J. Covid‐19: Supporting nurses' psychological and mental health. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2742–50. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.15307

32. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1924–32. DOI: 10.3201/eid1212.060584

Comments