Vitality Training Programme for people with fibromyalgia: ‘I’m good enough just as I am’

Course participants learn to shift their attention from disease to health, from a critical to an accepting attitude about themselves, and from despair to hope and belief in their own ability to cope.

Background: Fibromyalgia is characterised by widespread muscle pain and fatigue, and can result in a significant illness burden, sickness absence and a need for health services. Treatment options are limited, and many feel that they are met with little understanding. The Vitality Training Programme (VTP) is a group-based course that can improve a person’s ability to manage daily life in the presence of health challenges, and thus bolster their health and capacity to cope with the disease.

Objective: The study is part of a larger research project that seeks to improve the treatment options for people with fibromyalgia. The objective of this sub-study has been to investigate the experiences of people with fibromyalgia with the VTP course and the significance of the course for their daily lives.

Method: We conducted an explorative qualitative study comprised of individual interviews with six people, all women from 20 to 50 years of age. The interviews were held three to four months after completion of the VTP course. A semi-structured interview guide was used. The analysis employed Malterud’s approach for systematic text condensation.

Results: The course was significant for the participants’ daily life. In particular, the participants stressed the importance of recognising themselves in each other’s experiences and feeling accepted by the group. The analysis resulted in three main categories: 1) understanding oneself in light of the group, 2) the course as an arena for learning to accept oneself, and 3) dealing with the challenges of daily life.

Conclusion: The study shows that the VTP course can help people with fibromyalgia to relate to themselves and the disease in a more caring, accepting way. This entails changing their understanding, attitudes and actions regarding their own situation, which is especially crucial in the case of a complex, challenging illness such as fibromyalgia. The VTP course can help participants to shift their attention from disease to health, from a critical to a more accepting attitude towards themselves, and from despair to hope and belief in their own coping ability. Participants continued this process after completing the course. Group belonging was highly significant, especially for feeling accepted, recognised and supported.

Musculoskeletal disorders cause significant health challenges and are among the most frequent reasons for sickness absence and the need for health services (1, 2). Fibromyalgia is one of the most common musculoskeletal disorders in Norway, affecting 3–6 per cent of the population (1).

People with fibromyalgia experience widespread muscle pain, fatigue and sleep disturbances, and they can also have cognitive difficulties, digestive problems and depression (3). These challenges are described as an ongoing struggle that requires adjustments in daily life (4).

Common coping strategies include planning one’s daily life, reducing stress, employing distraction techniques and ‘putting on a mask’ in order to function normally (5, 6). Social support is crucial in daily life (5). People with fibromyalgia are generally in poorer health than the population as a whole (7). Women comprise almost 90 per cent of those with the diagnosis (8).

Despite the prevalence and burden of fibromyalgia, the diagnosis has low legitimacy (9). It is also controversial because the diagnosis cannot be confirmed with objective findings. Patients find the lack of understanding among healthcare professionals and in society to be a significant added burden (10).

International guidelines recommend that treatment focuses on improving the patient’s health-related quality of life through a holistic approach and recognition of the disease as complex and multidimensional (11).

Treatment should be personalised for the individual, and the patient should be actively involved in choosing the treatment options. Non-pharmacological interventions are recommended as first-line therapy. Research shows that the most effective approaches are physical activity and cognitive therapy (8, 11).

Group-based interventions may be beneficial

Group-based interventions that focus on self-management can have a positive impact on chronic disease, but more research is needed to ascertain which approaches work, for whom and for how long (12).

The Vitality Training Programme (VTP) is a group-based course aimed at enhancing the patients’ abilities to manage their lives with health challenges. It is conducted in groups of eight to twelve people. The course employs mindfulness practices, cognitive reflection exercises and various creative methods such as drawing, movement, music and picture cards to increase participants’ awareness of their own behavioural and thought patterns and of the potential to make new, more beneficial choices.

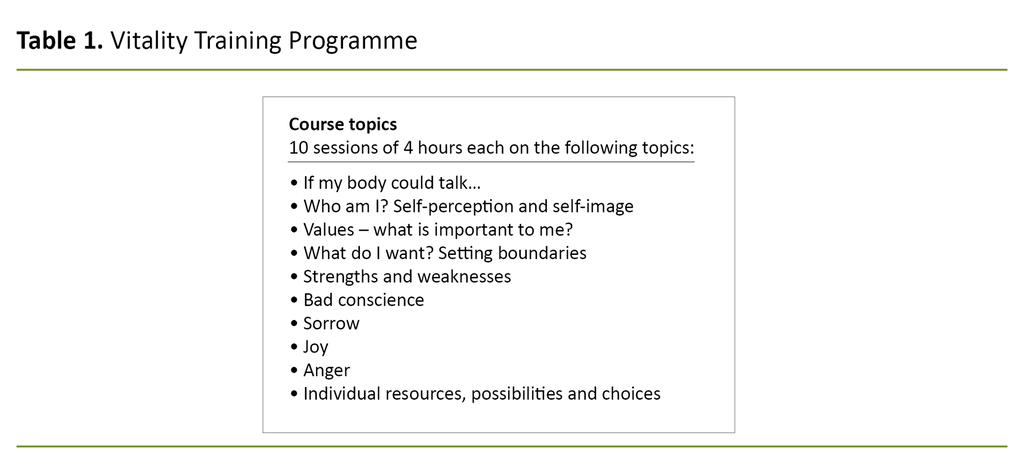

Participants in the VTP course endeavour to enhance their self-understanding. The course has been developed around ‘life topics’ that can be affected by living with long-term health problems (Table 1) (13, 14). The basis of the course is the relationship between thoughts, emotions and bodily experiences, as well as the recognition of individuals as self-experts (14). VTP course leaders are certified through a post-graduate education programme (15).

Importance of health promotion

The VTP course takes a health-promoting approach and is based partly on the theory of salutogenesis, which addresses how health is created and maintained (16, 17). The salutogenic model defines health on a continuum, focusing on the factors that promote health rather than on those that create disease.

The resources available to individuals, groups and society for counteracting stresses and strains are known as ‘resilience resources’, and include social support and active adaptation (17).

Previous research on the VTP course

The effects of the VTP course on chronic musculoskeletal pain and inflammatory arthritis has been evaluated in two randomised controlled trials (18, 19). These trials showed that participants had achieved less stress, better pain-coping ability and greater mental well-being. The effects continued or increased one year after the course ended.

In addition, the group with inflammatory arthritis experienced greater self-efficacy and less fatigue (18, 19). A qualitative focus group study showed that after completing the VTP course, people with rheumatic diseases had an altered understanding of themselves – both as a healthy person and as a person with an illness. They acknowledged their emotions and needs, and valued participating in a group where they were understood and taken seriously (20). Another qualitative study showed that the participants coped better with their pain and developed a heightened awareness of the relationship between their thoughts, emotions and bodily experiences and of their own resources (21).

Hallberg and Bergman note that people with fibromyalgia may benefit from group-based courses that recognise and support their efforts to cope with disease (6). The VTP may be such a course, but it has not been tested specifically in patients with fibromyalgia.

Objective of the study

Our study is a sub-study of the research project ‘Improved management of patients with fibromyalgia: evaluation of an integrated care model’ (ISRCTN96836577) conducted at the National Advisory Unit on Rehabilitation in Rheumatology in Norway (22).

The main study is a randomised controlled trial in which patients from 20 to 50 years of age with fibromyalgia attend the VTP course and then take part in personalised physical activity at a municipal Healthy Life Centre. The objective of our study was to investigate fibromyalgia patients’ experiences with the VTP course.

The research questions were as follows:

- How did people with fibromyalgia perceive their participation in the VTP course?

- What significance did the VTP course have for their daily lives?

Method

To gain insight into how people with fibromyalgia perceived and experienced the significance of the VTP course, we chose a qualitative, exploratory design with individual interviews (23, 24).

Recruitment

Participants from various course groups in the main study were invited via letter and telephone to participate in an interview. Five of the 13 people contacted agreed to take part. Those who declined said they had limited time or energy or that they did not want to participate.

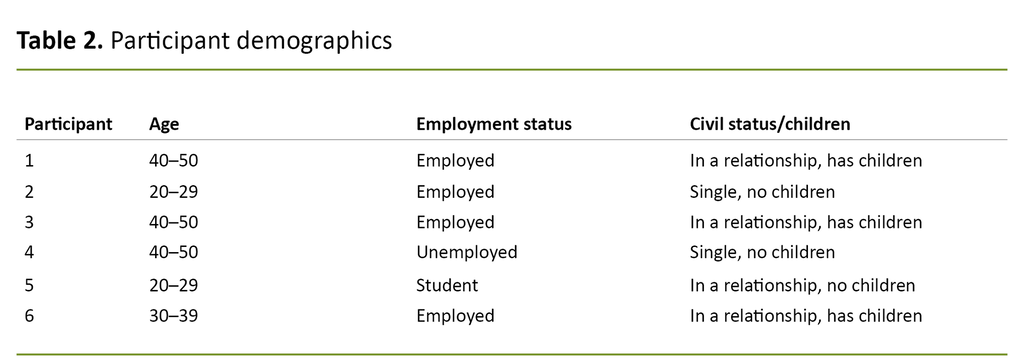

Due to the low response rate, we chose to include one additional person with fibromyalgia who had attended the VTP course outside of the main study (Table 2). Following the interviews, we felt that the same themes recurred and that we had collected a rich set of data. As a result, we decided to end recruitment to our study.

Ethical perspectives

The study has been approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC, reference number 2015/2447). Participation was voluntary, and participants signed a statement of informed consent. The participants were informed that they could withdraw during the study. The interview texts were anonymised during transcription.

We were intent on taking care of the participants and ensuring that we did not subject them to pressure during the interviews. We offered to have a follow-up conversation with the participants after the interview if they felt the need for it.

The interview process

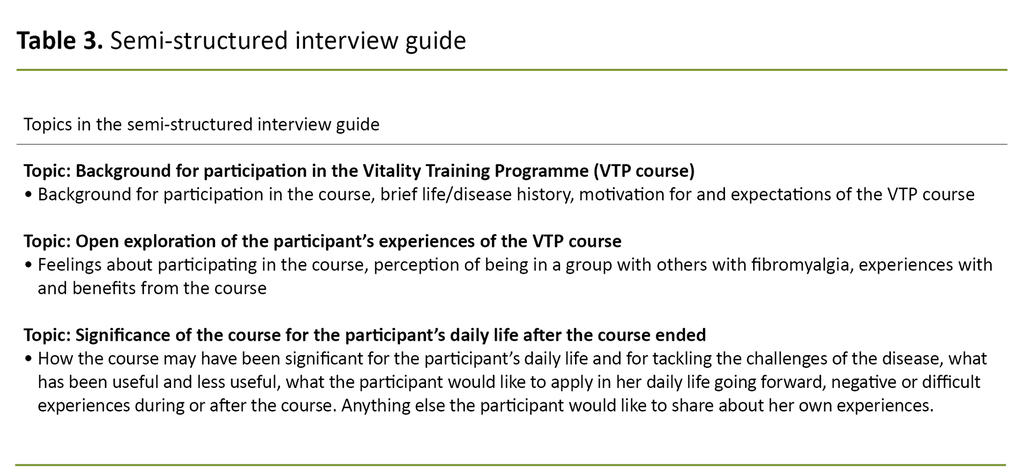

We wanted to gain knowledge about the lasting impact of the VTP course, so we chose to conduct the interviews three to four months after participants had completed the course. We began the interview by giving the participants information about the project, the purpose of the interview and the interviewer’s background, and then told them that their critical reflections were important. We developed a semi-structured interview guide focusing on the participants’ experiences, perceptions and reflections (Table 3).

The interviewer, who is the first author, took an open approach in order to avoid asking leading questions. The first author has training in VTP, but has not facilitated a course herself. She works with fibromyalgia rehabilitation and has a preunderstanding that fibromyalgia is a complex disease which can be difficult to live with and for which finding good treatment interventions is challenging. The interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes.

Analysis

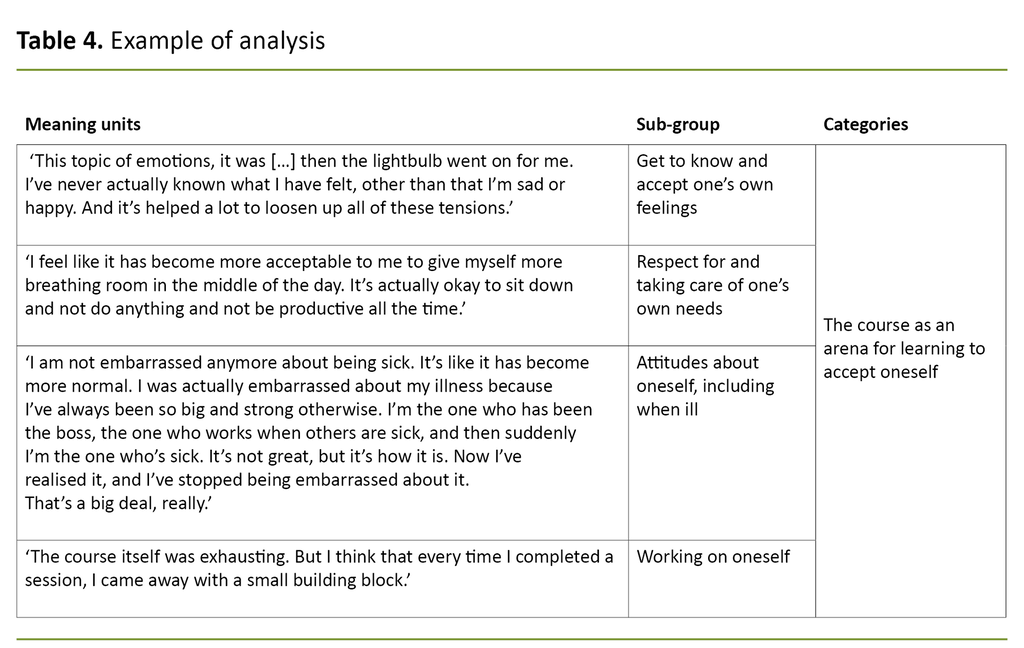

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, resulting in 90 pages of text. After the interviews, we made note of non-verbal signals and impressions. We employed Malterud’s approach to systematic text condensation using a four-step process (Table 4) (23).

The authors read each of the interviews separately and formed an overall impression (step 1). The first author identified meaning units by systemising the material into code groups (step 2).

All the authors took part in analysis seminars in which they discussed the code groups and sub-groups, and then created abstract meaning content categories. Due to our different backgrounds as researchers and clinicians, our comments and reflections in the analysis process varied widely (steps 3 and 4).

In the last phase (step 4), we synthesised the results by revisiting the interview texts and recontextualising the material (23).

Results

The participants had different life stories, as well as common experiences of living with a challenging disease and encountering a lack of understanding. Their reflections on the course were positive overall, and it appeared that the significance of the course for the participants was closely tied to their recognition of themselves in relation to the experiences of others and to the feeling of support and acceptance within the group.

The analysis process resulted in three main categories: 1) understanding oneself in light of the group, 2) the course as an arena for learning to accept oneself, and 3) dealing with the challenges of daily life.

Understanding oneself in light of the group

The participants talked about the importance of meeting others with the same diagnosis, which made them feel recognised and created a mutual understanding. This understanding and recognition were meaningful, especially because many of them had seldom encountered such attitudes before.

The disease had contributed to a negative self-understanding.

The disease had contributed to a negative self-understanding, and several of them described it as a feeling that ‘something was wrong’ with them as people. They said that the realisation that others in the group were ‘normal’ people with jobs, families, plans and interests gave them hope for the future. This helped to create a new self-understanding:

‘Just by meeting people with the same challenges, I saw that they were not abnormal, they were people. There’s nothing wrong with me, there are others who struggle with this too. I saw there are people in full vigour who are struggling with the same things as me.’ (Participant 1)

The group culture’s acceptance of differences was described as important, especially when touching on sensitive topics. The participants had different perceptions of the methods used in the course, such as picture cards, ‘uncompleted sentences’ and mindfulness exercises. Several stated that the methods paved the way for understanding new aspects of themselves.

Many admitted that they had put a great deal of pressure on themselves to cope. They had ignored their body signals and had been hard on themselves, resulting in more pain, fatigue and negative emotions. The participants said that they gained better insight into how they had managed the challenges of daily life and that the course showed them that change is possible.

Group belonging was significant

At the same time, they thought it was challenging to make changes and that it was easy to fall back into old patterns. One participant found it difficult when the course ended because she needed the group support to maintain her progress.

The acceptance shown by the group leaders contrasted with participants’ previous encounters with healthcare professionals.

Participants said the group culture and the group leaders were important aspects of the course experience and the benefits they got from it. They inspired, challenged and supported one another. A positive tone, openness and a high degree of tolerance created a sense of belonging and gave them the courage to work on themselves and to see themselves in new ways. The group leaders were described as ‘genuine, open and warm’. The acceptance shown by the group leaders contrasted with participants’ previous encounters with healthcare professionals.

The course as an arena for learning to accept oneself

The participants reflected a great deal on accepting their emotions and reactions, including anger. Several acknowledged that they had to work on their feelings because they had previously tried to block them out.

Several said that the course and the period afterward increased their respect for and acceptance of their own needs, and they gave themselves permission to attend to their needs and take themselves more into account. Many described how they had downplayed their own needs in the past, and admitted that this did not work well.

Some struggled to accept themselves

Some drew parallels with their childhood and upbringing: they were supposed to be smart, kind and not egotistical or angry. One participant felt embarrassed about being sick because it did not fit well with the demands of her job. The process of accepting oneself took time. It was not easy nor was it finished when the course was over. Consequently, the participants continued working on this after the course:

‘Being aware of how you treat yourself, I think that’s what has made me feel so much better. I’ve seen how hard I’ve actually been on myself, it’s not something I had thought about before. I thought it was totally normal.’ (Participant 6)

‘In a way, I’m a little kinder to myself. I’m good enough just as I am, even though I’m not perfect, so to speak.’ (Participant 1)

Difficult to work on oneself

Several said that it was both important and difficult to work on themselves. They explained that the course required active engagement on their part, which could be challenging.

Several emphasised that it is important to want to take such a course in order to benefit from it. One participant said that she chose to open up in the VTP course because it addressed her on a more personal level than other courses she had attended.

Dealing with the challenges of daily life

Participants explained in various ways that they gained more confidence in their own abilities and the potential to influence their daily life and health following the course. Some had previously received medical treatment that did not help, and they had to take matters into their own hands to improve their daily life.

During and after the course, several participants explored new ways of tackling their challenges, such as pain and fatigue, by making adaptations at work, giving up tasks, using a rucksack instead of a handbag, and taking breaks. They explained that making adaptations required having respect for the body’s signals and one’s own needs:

‘It’s good to know that the disease doesn’t get to decide everything, but that I can actually decide some things as well. And make decisions that affect the disease, not only that the disease affects me. This means that I myself have some control.’ (Participant 2)

Mindfulness helped to relieve stress

All the participants talked about stress in the interviews, and the course made many of them more aware of the factors that trigger stress in their daily lives. Several mentioned mindfulness as a method they learned that helped them to manage their stress, find calm and take more control. After the course, they used mindfulness in various ways:

‘I’ve learned to recognise signals that help me not to push myself too hard. That’s perhaps the most important thing. Noticing my stress level when it comes. I didn’t do that before. It doesn’t help for others to say it, you need to recognise it yourself. I think the course was very good at this – learning to notice it yourself.’ (Participant 6)

Participants took more control themselves

By attending the course, many participants became more aware of what was important to them and what brought joy to their daily life. They described how this helped them improve their self-regulation rather than allowing themselves to be controlled by external expectations and pressure to achieve.

They worked on finding a balance between what gives them energy and what takes it away. In addition, they strived to gain more control over where they direct their energy by setting priorities, saying no and risking the possibility of not meeting expectations. It took determination and effort to maintain the changes over time.

Discussion

The results provide insight into how the participants perceived the course and how the course was significant for their daily lives. Three to four months after the VTP course ended, the participants said that it had been meaningful and had helped to change their self-understanding, accept themselves better and engage in processes to find new ways of handling daily life.

With respect to perceptions of the VTP course, the findings show that the support and acceptance from the group had an impact on participants’ self-understanding. It was important to meet others in the same situation, and although it was difficult, focusing on their emotions and stress was crucial.

It was important to meet others in the same situation.

The understanding and attitudes that participants encountered in the group differed from those they had previously experienced. This created an opening for them to see themselves in a more positive light, and it highlighted how self-understanding is coloured by the attitudes projected by those around us. Many used to feel that they were ‘abnormal’.

This perception can be viewed in connection with the negative attitudes about fibromyalgia within society at large, including among healthcare professionals. Previous research has elucidated this type of burden (10, 25), and our study emphasises the responsibility of healthcare professionals and the importance of how patients are treated, for example, in a group-based course.

Participants changed their self-understanding

Understanding oneself and one’s life situation is important for health promotion (17). In the interviews, participants made it clear that changing their self-understanding had been important for them.

The women’s attitude about themselves evolved during and after the course, from being strict and critical to more accepting. As a group, they established legitimacy for taking care of and acknowledging themselves, which the participants found to be extremely important. These findings correspond with other research on VTP (20, 21).

The study highlighted the challenges arising from the pressure to achieve, and through the course the participants gained insight into how these challenges affected them. Group support appears to be especially crucial for people with complex health challenges, and this is seen in other studies as well (21, 26). Social support is regarded as an essential resiliency resource in health-promotion efforts (16). Our findings support this view.

Stronger belief in one’s own resources

Another principle related to health-promotion efforts that our study highlighted was attention to ‘life topics’ as opposed to ‘disease topics’. This gave participants the freedom to explore what feels valuable and meaningful and what they want and need, which can enhance the perception that life is meaningful in spite of its challenges (17).

Our study showed that by being active in their own process, the participants increased their belief in their own resources and the potential to influence their situation. The women experienced a progression from despair to more hope and belief in their own coping skills by discovering new perspectives, resources and possibilities. They explained that they got better at dealing with challenges and taking control of their daily lives, which impacted on their perception of and benefit from the VTP course. The results show that change is difficult and takes time, and that the process continues after the course ends. Participants may therefore need support over time to sustain the positive changes they have made.

They explained that they got better at dealing with challenges and taking control of their daily lives.

Previous research on recovery from fibromyalgia has shed light on this demanding process. Recovery can occur through an individual, active and comprehensive process of getting one’s daily life to function satisfactorily (27, 28). This research aligns with international treatment recommendations regarding a personalised and holistic approach (11). Studies have also shown that people with complex diseases may benefit from a group setting to explore how to manage their daily lives (20, 21).

Weaknesses of the study

Although a group-based course may enhance a patient’s health and coping skills, it is uncertain whether a group setting is suitable for everyone. One study on participation in group-based courses showed a bias in participation towards women with a high socioeconomic status and optimal health-related behaviour (29).

All participants in our study were women, which raises the question of why only women wished to take part and whether the VTP course is less appealing to men. Many of those asked declined to participate, and we do not know whether a different sample would have given different results.

The informants believed that the group and the leaders were significant for how they perceived the VTP course and the benefit they gained from it. However, they also stressed that the content of the course was important for the changes they had made.

In a study of 35 different group-based initiatives for chronically ill people, Nossum et al. found that the group process and activation in group-based courses were more important than the course content itself (30). In our study, it is unclear which factors were most relevant for coping with illness, and more research is therefore needed.

Although we chose to conduct open interviews and stressed to the participants that we wanted their honest feedback as well as critical reflections, the authors’ preunderstanding may have influenced the analysis process. The group of authors represents different experiences, and the analysis emphasised critical perspectives and new questions to create distance from our own preunderstanding. Although we had a rich data set, a larger sample would have strengthened the study.

Conclusion

The study shows that the VTP course was significant for the women with fibromyalgia because they learned to think about themselves and the disease in new ways. The women found it difficult, but important, to work on their self-understanding, attitudes and management of their daily lives, and they continued this process after the course was completed.

The VTP course helped to shift the participants’ attention from disease to health, from a critical to an accepting attitude about themselves and from despair to hope and belief in their own ability to cope. The sense of group belonging contributed to acknowledgement, recognition and support, and these findings correspond with previous research on the VTP.

The study illustrates the vulnerability of groups with controversial diagnoses and the importance of how they are treated by healthcare professionals. It also shows that groups who struggle with chronic disease may benefit from meeting others in the same situation.

References

1. Kinge JM, Knudsen AK, Skirbekk V, Vollset SE. Musculoskeletal disorders in Norway: prevalence of chronicity and use of primary and specialist health care services. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2015;16:75–84.

2. Folkehelseinstituttet. Folkehelserapporten – Helsetilstanden i Norge. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 2018. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/hin/ikke-smittsomme/muskel-og-skjeletthelse/ (downloaded 01.09.2019).

3. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care & Research. 2010;62:600–10.

4. McMahon L, Murray C, Sanderson J, Daiches A. «Governed by the pain»: narratives of fibromyalgia. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2012;34(16):1358–66.

5. Traska TK, Rutledge DN, Mouttapa M, Weiss J, Aquino J. Strategies used for managing symptoms by women with fibromyalgia. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(5-6):626–35.

6. Hallberg LRM, Bergman S. Minimizing the dysfunctional interplay between activity and recovery: A grounded theory on living with fibromyalgia. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2011;6(2).

7. Hoffman DL, Dukes EM. The health status burden of people with fibromyalgia: a review of studies that assessed health status with the SF‐36 or the SF‐12. Health status burden in FM. International Journal of Clinical Practice (Esher). 2008;62:115–26.

8. Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1547–55.

9. Jære L. Fibromyalgi har lavest prestisje. Forskning.no. 15.01.2018. Available at: https://forskning.no/2018/01/sykdommers-prestisje/produsert-og-finansiert-av/universitetet-i-oslo (downloaded 01.09.2019).

10. Sim J, Madden S. Illness experience in fibromyalgia syndrome: a metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(1):57–67.

11. Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Fluß E, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76(2):318–28.

12. Stenberg U, Haaland-Øverby M, Fredriksen K, Westermann KF, Kvisvik T. A scoping review of the literature on benefits and challenges of participating in patient education programs aimed at promoting self-management for people living with chronic illness. Patient Education and Counseling. 2016;99(11):1759–71.

13. Zangi HA, Haugli L. Vitality training – a mindfulness- and acceptance-based intervention for chronic pain. Patient Education and Counseling. 2017;100(11):2095–7.

14. Steen E, Haugli L. The body has a history: an educational intervention programme for people with generalised chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient Education and Counseling. 2000;41(2):181–95.

15. VID vitenskapelige høgskole. Videreutdanning i livsstyrketrening. Oslo: Vid vitenskapelige høgskole. Available at: http://www.vid.no/studier/livsstyrketrening-videreutdanning/ (downloaded 12.03.2019).

16. Langeland E. Salutogenese og psykiske helseproblemer: en kunnskapsoppsummering. Trondheim: Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for psykisk helsearbeid; 2014.

17. Antonovsky A, Sjøbu A. Helsens mysterium: den salutogene modellen. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2012.

18. Haugli L, Steen E, Lærum E, Nygard R, Finset A. Learning to have less pain – is it possible?: A one-year follow-up study of the effects of a personal construct group learning programme on patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient Education and Counseling. 2001;45(2):111–8.

19. Zangi HA, Mowinckel P, Finset A, Eriksson LR, Høystad TØ, Lunde AK, et al. A mindfulness-based group intervention to reduce psychological distress and fatigue in patients with inflammatory rheumatic joint diseases: a randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2012;71(6):911.

20. Zangi HA, Hauge M-I, Steen E, Finset A, Hagen KB. «I am not only a disease, I am so much more». Patients with rheumatic diseases' experiences of an emotion-focused group intervention. Patient Education And Counseling. 2011;85(3):419–24.

21. Steen E, Haugli L. From pain to self-awareness – a qualitative analysis of the significance of group participation for persons with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient Education and Counseling. 2001;42(1):35–46.

22. Haugmark T, Hagen KB, Provan SA, Bærheim E, Zangi HA. Effects of a community-based multicomponent rehabilitation programme for patients with fibromyalgia: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6).

23. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

24. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3rd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

25. Werner A, Isaksen LW, Malterud K. ‘I am not the kind of woman who complains of everything’: Illness stories on self and shame in women with chronic pain. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(5):1035–45.

26. Werner A, Steihaug S, Malterud K. Encountering the continuing challenges for women with chronic pain: recovery through recognition. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(4):491–509.

27. Grape HE, Solbrække KN, Kirkevold M, Mengshoel AM. Staying healthy from fibromyalgia is ongoing hard work. Qualitative Health Research. 2015;25(5):679–88.

28. Mengshoel AM, Heggen K. Recovery from fibromyalgia previous patients' own experiences. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2004;26(1):46–53.

29. Knutsen IR, Bossy D, Foss C. Passer gruppebaserte lærings- og mestringstilbud for alle med diabetes 2? Sykepleien Forskning. 2017;12(60171):(e-60171). DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2017.60171

30. Nossum R, Rise MB, Steinsbekk A. Patient education – Which parts of the content predict impact on coping skills? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2013;41(4):429–35.

Comments