The contribution of a master’s degree to clinical practice

Anaesthesiology and intensive care nursing are regarded as practice-oriented professions. Can a master’s degree provide an equally high level of skill and theoretical knowledge as specialist training?

Background: Educational programmes in advanced practice nursing are switching from specialist training to a master’s level education. In general, there is a positive attitude towards master’s degrees, but some have objections regarding ‘‘academisation’’ and ‘over-qualification’.

Objective: To investigate the expectations that the anaesthesiology and intensive care professions have of master’s level competence.

Method: We conducted three focus group interviews with anaesthesiology and intensive care nurses in three health trusts. They were managers, advanced practice nurse mentors, experienced nurses and recent nursing graduates. We used thematic content analysis to analyse and interpret meaning systems. The expectations of informants regarding master’s level competence were gleaned from the positive and negative statements made during the interviews.

Results: At the master’s degree level, informants expect that nurses’ scientific language and critical thinking ability will be further developed, be integrated into professional knowledge and professional practice, and be reflected in the way nurses present themselves and interact. Many expect nurses with master’s degrees to have a higher level of competence and greater potential for satisfying the requirement of evidence-based practice (EBP). Anaesthesiology and intensive care nursing are regarded as practice-oriented professions, and there are concerns as to whether master’s degree programmes provide an equally high skill level and theoretical knowledge as specialist training.

Conclusion: The added value of a master’s degree programme is found in the scientific language and critical thinking skills, as well as in the application of evidence-based practice. Health trusts and educational institutions should cooperate closely on developing educational models, study programmes and pedagogical approaches so that the skill level is maintained in a master’s degree programme.

Most educational institutions in Norway are converting their specialist training in advanced practice nursing to master’s degree programmes. This process is rife with opposing views and concerns about the consequences of this change, at both the societal level and the local level.

Background

Until a few years ago, specialist training in anaesthesia and intensive care nursing did not result in an academic degree. For the first time in spring 2014, advanced practice nurses at two of Norway’s 15 educational institutions in anaesthesia and intensive care nursing graduated with a master’s degree comprised of 120 credits. Eight of the 15 educational institutions in Norway offer master’s studies in anaesthesia and intensive care nursing (1). The design, structure and models vary somewhat, but the programmes largely meet the requirements of the framework plans and are function oriented (1–4).

A national study showed a distinction in the learning outcome descriptions for the subjects ‘philosophy of science’, ‘methodology’ and ‘innovation’ between specialist training and a master’s degree in intensive care nursing (1). For specialist training, the learning outcomes for these subjects were designated as cycle 1-level (bachelor) (1, 5). The learning outcome descriptions in subjects such as ‘intensive care nursing’, ‘physiology/pathophysiology’, ‘pharmacology’ and ‘intensive care medicine’ were designated as cycle 2-level (master). It is reasonable to assume that the same holds true for anaesthesiology nursing, as these two fields have developed parallel to each other.

There are several reasons for switching from specialist training to a master’s degree programme. The Bologna Accord has been especially significant in this regard, as it set the goal of developing comparable educational programmes in Europe for the three tiers of degrees: bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. (6). The Bologna Process is referred to as a ‘quiet revolution’ in the three levels of nursing education, and is characterised by slow progress and few scientific studies to refer to (7, 8).

Discourse characterised by ‘master’s obsession’

In general, there is a positive attitude towards the master’s degree throughout Norway, but some also express objections and concerns which come to light in discourse at the general and local levels. In this context, discourse is defined as a meaning system that plays a role in constituting practice and is reflected in language as social practice (9). Discourse has been characterised by linguistic representations such as ‘function-oriented master’s’, ‘master’s obsession’, ‘avoiding a dead end’, ‘over-qualification’ and ‘a master’s degree is not a master’s degree’ (2, 10–12).

There are many arguments in favour of a master’s level education, often related to increased recruitment and the need for changes in competence. This is due to changes in demographic factors in society, changes in the population’s disease profile, developments in medical technology and requirements related to evidence-based practice (EBP) (13–18). There are also arguments for the need to change the autonomy of the health professions by a blurring of roles and developing new functions in the form of advanced clinical nursing (19–22).

In 2012, a Swedish report described a lack of adaptations for meaningful academic learning in the educational and practice field of specialised educational programmes (23). The report concluded that teachers must stand together on a pedagogical platform, and the field of practice must support and utilise the academic competence of recent graduates (23). Another Swedish study emphasised that methodology must be adapted to the professional field (24).

Academisation is a natural part of development

In a study from 2015, 18 practice supervisors in anaesthesiology, intensive care, surgery and cancer nursing viewed academisation as a natural part of development in society: All higher education should be at the bachelor’s, master’s or Ph.D. level, and a master’s degree is a prerequisite for ensuring future recruitment to advanced practice nursing (25). The informants said they had expectations that a master’s level education in the field should contribute something different than, for example, a master’s degree in administration, sociology and the like.

In a 2016 report from the Norwegian Association of Higher Education Institutions, a systematic search of international literature was conducted on the added value of a master’s degree in nursing (26). The conclusion was that nurses with a master’s degree made a positive contribution to the quality of services and patient safety. However, the report found no systematic evaluations of the contributions of advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree compared to nurses with specialist training. The report recommends further research that evaluates the added value of a master’s degree versus specialist training in a Norwegian context (26).

The fields of practice have little or no experience with what advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree represent. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to describe the opinions and expectations of the field of practice regarding the ways in which advanced practice nurses with a master’s level education working in anaesthesiology departments and on intensive care wards can contribute to clinical practice.

Method

This study is a collaboration between Oslo and Akershus University College (HiOA) and the University College of Southeast Norway (HSN). Both educational institutions have programme models with a design and structure that make the programmes comparable. They offer nursing students the opportunity to conclude their studies as advanced practice nurses after three semesters or continue on to carry out a master’s thesis for one semester at HSN and two semesters at HiOA. The university colleges also offer supplementary studies for previously educated anaesthesiology and intensive care nurses.

We conducted the study at the hospital health trusts in Buskerud, Vestfold and Telemark counties. The study has a qualitative, explorative and descriptive design. We chose to carry out focus group interviews with three groups comprised of anaesthesiology and intensive care nurses. Focus group interviews encourage a discussion among informants, and thus provide insight into the meaning systems that represent the professional environment in daily practice (27–29).

Sample

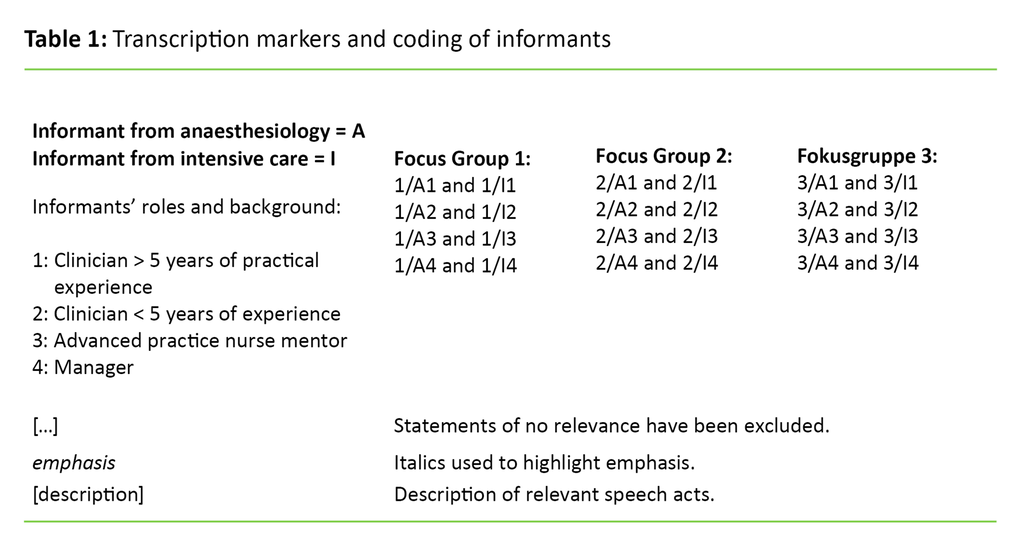

The sample consisted of advanced practice nurses with a variety of experiences, expectations and positions on the ward. They were managers, advanced practice nurse mentors, experienced nurses and recent nursing graduates (Table I). About one-third of the informants have an educational background from the time of in-house specialist training. The informants were selected by the managers to ensure that different opinions about a master’s level education and voluntariness were represented.

Of the 24 informants, four managers or advanced practice nurse mentors were pursuing master’s studies at the time (a cross-disciplinary master’s and a master’s in administration and management). This study was approved by the Data Protection Official for Research. The informants have given their written, informed consent to participate.

Data collection

The lead author conducted the interviews and the second author took notes during the interviews. Initially we wanted the informants to be candid and different opinions to be voiced. We conducted a partially structured interview on three topics to bring out the informants’ ‘understanding and expectations related to master’s level competence’, ‘reflections on the consequences of switching to master’s studies’ and ‘the attitudes they experienced within the professional environment regarding master’s degree programmes’.

We conducted all of the focus group interviews with seven of eight invited participants. The duration was approximately 80 minutes. Illness, a lack of staffing, and a misunderstanding about the number of people to be selected for the focus group interviews were reasons that the groups were not full. One group lacked a manager from the anaesthesiology department. This manager wrote a brief statement based on the three topics from the focus group interviews. The other two groups did not have any intensive care nurses with more than five years of practice.

We recorded the interviews, transcribed them and anonymised them. Table 1 shows a selection of markers that are intended to capture explicit statements of opinion and in part how emotional expressions, body language and phonetics can represent implicit, ambiguous statements (30–32). We chose to use transcription markers that were not too detailed so that the text would flow without too many codes that would limit the ability to gain an overview of interactions, topics and the process.

Analysis

To analyse and interpret the meaning systems, we chose to use thematic content analysis, which is a methodological analysis tool to focus and process the material thematically (33). We chose to use an inductive, rich description of the data across the focus group interviews, paying particular attention to explicit statements.

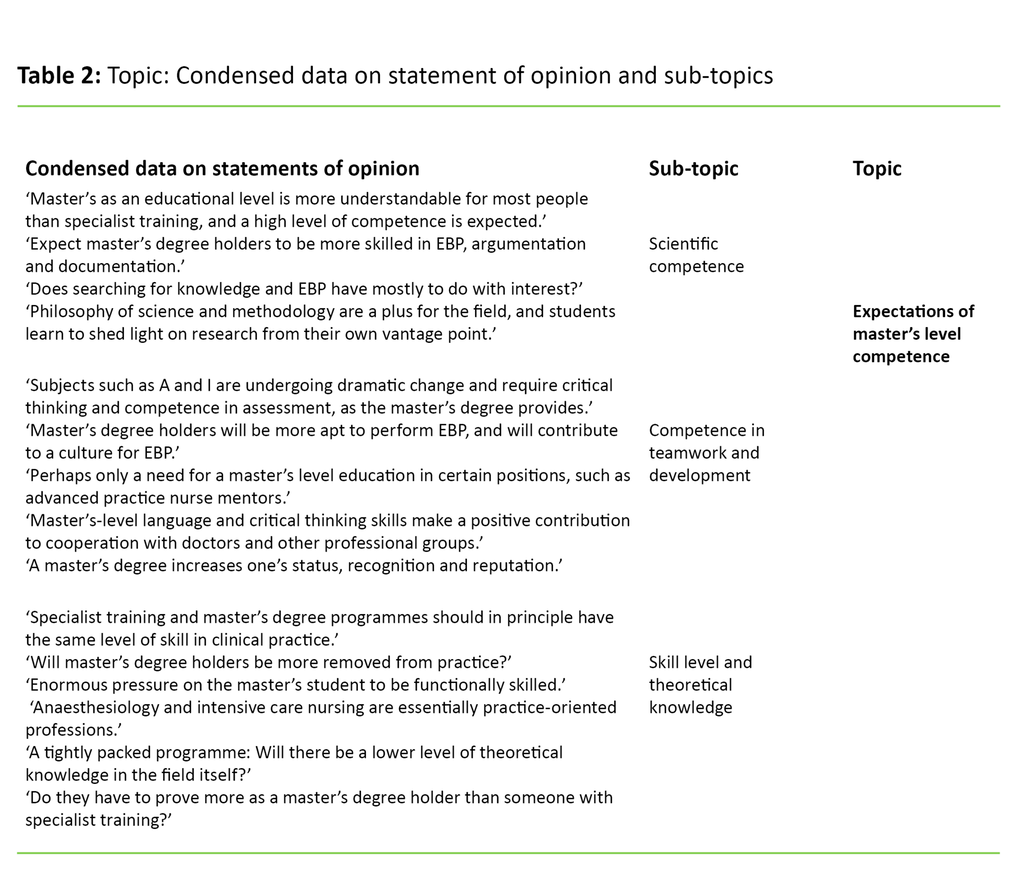

We condensed the meaning-related data by searching for meaning patterns around positive and negative expectations of master’s level competence. The patterns were analysed and structured in topics and sub-topics.

We used the concept of ‘expectation horizon’ as an analytical perspective when we analysed the statements of opinion (34). When we use the term ‘expectation horizon’ as a metaphor, we give extra attention in the analysis to what the informants believe are future scenarios and consequences of switching to a master’s degree programme.

Results

Table 2 shows three multifaceted sub-topics based on how the conversations revolved around positive and negative statements regarding master’s level competence.

- Scientific competence

- Competence in teamwork and development

- Skill level and theoretical knowledge

In the presentation of the results, we attempted to provide insight into the interview process and the distribution of statements of opinion among the informant categories and groups. We have selected quotes to show thematic representativeness, diversity, objections and opportunities. To limit the number of quotes, we have selected a sample that illustrates the overall content of opinion.

Scientific competence

In the first part of the interviews, the informants made somewhat different statements about their understanding of the special competence of master’s degree holders. As they talked, they came to a more limited and common understanding of this. Especially in Group 3, but also in Groups 1 and 2, the informants had little knowledge of the master’s degree programme:

‘I think we have good advanced practice nurses now […] What more should we expect?’ 2/I4

An informant had reflected on how most people understood what a master’s level education entails:

‘Everyone knows what a master’s degree is – it’s something everyone is familiar with, but when I say I have specialist training, people ask: ‘What is that?’ So a master’s degree certainly has more meaning!’ [Others around the table nodded in agreement]. 1/I1

After we had completed the introductory interviews, most of the informants said they expected that advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree would have more knowledge about EBP than those with specialist training. They expected that identifying and using new research would come more naturally to those with a master’s degree:

‘No doubt you’ll have this more at your fingertips just as in the practical work.’ 1/I1

Some also had the opposite view:

‘Doesn’t EBP have something to do with your interests as an advanced practice nurse? Using research articles – searching? Do you need to get a master’s degree for that?’ 2/A2

Many said that they expected advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree to be more analytical and critical, and therefore to ask more questions about current practice: ‘The positive aspect, I think, is that there might be a more critical view of what we are doing – that we offer the best and most careful treatment there is.’ 2/I3

‘By conducting research ourselves in our own field, we will in the long term gain insight from research from our own perspective instead of acquiring information through others’ research.’ 3/A2

‘A master’s degree will enrich the field. They think a little differently in their daily work than those without a master’s degree, because you learn to base your thinking on research. They learn to look things up and rely on research instead of saying “We have always done it that way”.’ 1/A3

Competence in teamwork and development

This sub-topic is developed based on how the informants view the switch from specialist training to a master’s degree programme as a kind of secondary benefit. Both professional groups felt that their fields were changing all the time, which requires practitioners with critical thinking skills, teamwork and renewal. Many assumed that more nurses with a master’s degree on their ward would enrich practice because it would be easier to enact change when a number of people think along the same lines. Some reflected on how this could perhaps lead to cultural change:

‘As a manager, I expect that those who have this type of education [master’s degree] will make a significant contribution to the ward! Bring the other employees along with them – participate and shape practice.’ 1/I4

‘Perhaps this can be a small stepping stone so that we can change some of the culture.’ 3/I4

Many also said they had expectations that a master’s level education develops a person’s thinking and language and that this would raise the level of dialogue with cooperating partners and possibly increase recognition:

‘[…] the language you use – that you carry more weight when know the subject – and can demands things in a way.’ 1/I3

‘We need to get better at speaking up. Be very specific, because we sit in the nurses’ station, and we have so many thoughts and opinions about this and that – and nothing comes of it!’ 2/A4

‘The nurse will get more recognition when you steer things more towards research and appeal to that rather than to opinion – you will get much more recognition and your voice will be heard.’ 1/A3

Skill level and theoretical knowledge

On the whole, the informants viewed the fields as practice-oriented professions. Concern was expressed as to whether the wards had enough to offer advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree. In all three groups, there were many who more or less shared this concern. Group 2 stated:

‘Our profession is very practical! That is the crucial element, and in fact we must hold fast to it.’ 2/A3

‘I’m very concerned about how this will be applied afterwards [when the degree is completed]. How satisfied will they be working at the anaesthesia table or hospital bed, and what adaptations must be made afterwards?’ 2/I4

Several regarded clinical studies in specialist training as comparable to the master’s level:

‘With regard to practice and the typical specialist training, I can’t see any great difference!’ 1/I1

Many were concerned that master’s studies might not produce functionally skilled advance practice nurses on par with specialist training.

‘Could we end up with less qualified advanced practice nurses, I mean, with regard to the practical part of the job? They had more than enough to do for one and a half years before they were good enough at the patients’ bedside. This might not be because they have had so much formal education in methodology and such. And it will take a much longer time on the job before they really can do everything – so that we are sure they have the experience we really need them to have.’ 2/I4

‘Maybe there has been a fear that nurses with a master’s degree may be more removed from the practical aspects of the job – this is one assertion. We have spoken with advanced practice nurse mentors and midwife mentors who have worked with three year groups of master’s graduates. Those who have taken a master’s degree versus those without a master’s are not more removed from the field of practice, but are rather on an equal footing.’ 1/I3

Other informants said that practical skills would not be a problem, but that there is a huge amount of material that master’s students must learn in the programme, and it is impossible to acquire all of it, especially in the beginning. They questioned whether nurses with a master’s degree would manage to have adequate theoretical knowledge:

‘Can you absorb what you are supposed to learn about anaesthesiology and intensive care – in addition to taking a master’s degree? […] Do they have sufficient academic knowledge? […] Do they know their theory? […] Is there enough time to become a good anaesthesiology nurse? […] You must have both the theory behind a master’s degree and you must know the anaesthesiology field. And you are going to manage that in two years? I am less concerned about skills. You can spend time on those when you are finished [some around the table nod in agreement], as long as you have the theory under your belt.’ 1/A3

Discussion

The analysis gives insight into the opinions and expectations of a sample of anaesthesiology and intensive care nurses regarding master’s level competence. Some ask: ‘What are we supposed to do with a master’s degree?’, while others expressed expectations of a positive difference between specialist training and a master’s degree programme.

Performance of evidence-based practice

In this section we will discuss the question ‘Will nurses with a master’s degree be more competent in the performance of evidence-based practice?’ There is a general view among the informants that anaesthesiology and intensive care nursing are essentially practice-oriented professions, but that the development of the health care services requires a high level of competence to work according to EBP to take the best possible care of the patient.

They point out that the professional fields are changing all the time. This means that nurses must develop their ability to think analytically and critically, which will be strengthened in a master’s degree programme. This view corresponds with a previous study showing that a master’s degree is expected to provide more training in critical and analytical thinking compared with specialist training (23).

The informants anticipate that advanced practice nurses who take a master’s degree in the future will have more competence in evidence-based practice (EBP), argumentation and documentation, and that they will contribute to a culture that promotes EBP. Not everyone in the initial focus groups expressed this view explicitly, but this is an understanding that developed during the course of the interviews.

Early in the group interviews, representatives of all the informant categories say that they are uncertain or do not understand what a master’s level education is supposed to be used for. They are satisfied with the advanced practice nurses with specialist training and believe that a search for knowledge and EBP have mainly to do with interest. Among the informants, only those at the management level – two managers and one advanced practice nurse mentor – have or were pursuing a master’s degree at the time, and they say they know what a master’s level education entails.

Nobody has experience with the added value that master’s level competence can provide to nursing services and the working environment. One of the managers says that master’s level competence is needed only for certain positions, such as a nurse mentor. Otherwise it is managers and advanced practice nurse mentors in particular who support and justify the need the most. They do so based on their expectations that advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree will be a driving force for developing better services for patients and a culture for EBP on the wards. It is reasonable to assume, as the informants argue, that advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree will have more training in literature searches, have the ability to read research articles more critically and take an academic approach to knowledge.

EBP is part of a common thread in the educational pathway towards the two master’s degree programmes. This topic has been strengthened in the new programmes. However, there is a limited amount of time and attention that EBP can be given in the 30 credits that have been added in the changeover from specialist training to master’s studies.

In a study of a cross-disciplinary master’s degree programme in EBP at the University of Bergen, Hole et al. describe findings showing that those with a master’s degree are regarded as change agents in EBP at their workplaces (35). The study has 120 credits to develop competence in EBP and emphasises the development of competence in performance. Cycle 2, the master’s level, includes a requirement to advance new ways of thinking and innovation. Competence in performance is included as a part of competence in innovation. There are few parameters for developing such competence in the master’s programme for anaesthesiology and intensive care nurses.

Level of knowledge

Here we discuss the question ‘Will nurses with a master’s degree have a lower level of skill than recent graduates?’ The informants are concerned whether the skill level of clinical practice will be reduced following a switch to master’s level education. Many are familiar with the educational programmes from the time when they took part in in-house specialist training lasting 18 to 24 months. They have followed the development from the transition to university colleges, updating of framework plans and a reduction of 18 months in specialist training.

Many make statements suggesting they believe that specialist training and a master’s degree programme should in principle have the same level of skill in clinical practice. This view is reflected in a previous study which found that learning outcome descriptions for specialist training and a master’s degree programme in clinical studies are formulated in much the same way and at an advanced level (1).

It is mainly theoretical courses that represent academic competence, such as the philosophy of science and methodology, in which the level is described as being comparable to the bachelor’s level. In a new report, the Norwegian Association of Higher Education Institutions also describes the level of specialist training as high and to some extent beyond the requirements of the framework plans and that the step up to the master’s level is short (26).

In a master’s degree programme, the courses on the philosophy of science and methodology have become more extensive and demanding. These courses are intended to be completed over three semesters, comparable to specialist training without a master’s thesis. The informants’ concerns revolve around how the master’s students will manage to complete new courses, acquire functional skills and at the same time have an equally high level of theoretical knowledge, as after completion of specialist training.

Theoretical knowledge is valued so high that one of the advanced practice nurse mentors prioritised it over acquisition of a full range of functional skills within the timeframe of the educational programme. She believed that advanced practice nurses can develop the practical skills after completing their education if they have good theoretical knowledge. The framework plans require advanced care nurses to possess functional skills and competence in taking appropriate action (3, 4).

It is quite challenging from a teaching perspective to ensure that students acquire advanced clinical competence and at the same time satisfy the academic requirements set for a master’s degree programme. Many of the informants regarded these requirements as almost impossible to fulfil, and thus they should be evaluated on an ongoing basis.

The field’s reputation and competence in teamwork

In this section we discuss the question ‘Will a master’s level education help to enhance the field’s reputation and increase competence in teamwork?’ The philosophy of science and methodology are positive for the field in that students learn to elucidate research from their own vantage point. As nurses acquire a higher level of scientific language and strengthen their ability to think critically, the informants expect that cooperation between advanced practice nurses and doctors and other professional groups will be on a more equal footing, that their opinions will more likely be taken into account and that they will experience greater respect for their own views.

The importance of language for creating a better common understanding and appropriate cooperation across professional groups is undeniable (32). It is a huge leap to go from linguistic representations such as an ‘in-depth subject paper’, which is a school assignmentin specialist training, to a ‘master’s thesis’, which is an academic project. This is not only a linguistic representation that sounds impressive, but it is also a step up in quality that is expected to be reflected in practice and which most people understand and recognise. Advanced practice nurses who have taken specialist training are recognised for their high skill level (35). Further recognition assumes that a master’s level education maintains a high theoretical level and skill level.

Critique of methodology

Both authors of this article, who also conducted the interviews, have many years of professional affiliation with the fields of intensive care and anaesthesiology nursing. As facilitators with deep insight into the culture and use of language, and great openness with regard to differing opinions, it is reasonable to assume that their competence has contributed to a rich, diverse data collection. In particular, the second author, who has not had knowledge of or contact with the professional environments in the study, has brought an outside view to the data.

We have asked ourselves whether the lack of one informant in each group may have affected the interviews. In cases when an experienced advanced practice nurse was not present, the advanced practice nurse mentors have mostly represented the perspective of those with experience in the field. The dynamics of the group without a manager from the anaesthesiology department would perhaps have been different if the manager had been present.

Conclusion

It is natural to expect that an extensive, national restructuring of specialist training to a master’s level education will be characterised by ambivalence, approval and opposition. This study describes the reflections of highly competent informants on expectations of a master’s degree programme versus specialist training. The study also shows that clinicians and managers need more knowledge about what a master’s level education entails.

At the master’s degree level, informants expect that nurses’ scientific language and critical thinking ability will be further developed, be integrated into professional knowledge and professional practice, and be reflected in the way nurses present themselves and interact. Informants’ linguistic representations regarding master’s level competence indicate an expectation about the future in which advanced practice nurses with a master’s degree will be better prepared to help to establish EBP due to their academic competence as role models and catalysts in practice. The master’s level education puts an overall emphasis on EBP, but the expectation of strengthening competence in performance among the students creates challenges within the current parameters of the master’s degree programme.

As a result of the Bologna Accord, master’s degree programmes are here to stay. We strongly recommend that health trusts and educational institutions work closely together to develop educational models and adapt pedagogical approaches so that there is an appropriate balance between academic competence, theoretical knowledge and skill level.

References

1. Skogsaas B, Karlsen MMW. Fra videreutdanning til mastergradsstudium. Sykepleien, 2015;103:3:56–9. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2015/02/fra-videreutdanning-til-mastergradsstudium(downloaded 20.09.2017).

2. Lerdal A. Vi trenger funksjonsorienterte mastergrader. Sykepleien Forskning, 2014;9:2:103. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/2014/06/vi-trenger-funksjonsorienterte-mastergrader(downloaded 20.09.2017).

3. Kunnskapsdepartementet. Rammeplan for videreutdanning i intensivsykepleie. 2005. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/kd/pla/2006/0002/ddd/pdfv/269388-rammeplan_for_intensivsykepleie_05.pdf (downloaded 20.09.2017)

4. Kunnskapsdepartementet. Rammeplan for videreutdanning i anestesisykepleie. 2005. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/kd/pla/2006/0002/ddd/pdfv/269383-rammeplan_for_anestesisykepleie_05.pdf (downloaded 20.09.2017)

5. Kunnskapsdepartementet. Nasjonalt kvalifikasjonsrammeverk for livslang læring. 2011. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/vedlegg/kompetanse/nkr2011mvedlegg.pdf (downloaded 20.09.2017)

6. Collins S, Hewer I. The impact of the Bologna process on nursing higher education in Europe: A review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2014;51:150–6.

7. Davies R. The Bologna process: the quiet revolution in nursing higher education. Nurse Education Today 2008;28:935–42.

8. Palese A et. al. Bologna Process, More or less: Nursing: education in the European Economic Area: A discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 2014;11:1–11.

9. Fairclough N. Language and power. 2. ed. London: Pearson Educational; 2001.

10. Mastad V. Videreutdanning i ingenmannsland? Available at: http://sykepleien.no/2012/02/videreutdanning-i-ingenmannsland(downloaded 14.04.2014).

11. NOKUT. En mastergrad er ikke en mastergrad. Mastergrader ved statlige og private høgskoler. Rapport; 2012;6. Available at: http://www.nokut.no/Documents/NOKUT/Artikkelbibliotek/Kunnskapsbasen/Rapporter/UA/2012/Hegerstr%C3%B8m_Turid_Mastergrader_ved_statlige_og_private_h%C3%B8gskoler_2012-6.pdf(downloaded 20.09.2017).

12. Hellesø R. Utdanning for fremtiden. Available at: http://www.dagsavisen.no/nyemeninger/utdanning-for-fremtiden-1.451424 (downloaded 04.05.2014).

13. Analysesenteret. Rapport ABIO Ressurs. Rapport på oppdrag fra Norsk Sykepleierforbund. 2015. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/2591005/Rapport%20ABIO%20Ressurs.pdf(downloaded 20.09.2017).

14. NSF Rapport. Fremtidens spesialsykepleiere. Krav til spesialiststruktur, utdanningskvalitet og dimensjonering. 2016. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/2976737/cache=1465980149000/Fremtidens_spesialsykepleier_pdf.pdf(downloaded 20.09.2017).

15. Helsedirektoratet. Behovet for spesialisert kompetanse i helsetjenesten. En status-, trend- og behovsanalyse fram mot 2030. Rapport IS-1966; 2012. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/190/Behovet-for-spesialisert-kompetanse-i-helsetjenesten-en-status-trend-og-behovsanalyse-fram-mot-2030-IS-1966.pdf (downloaded 20.09.2017).

16. St. meld. nr. 47 (2008–2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett handling – på rett sted til rett tid. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-47-2008-2009-/id567201/ (downloaded 20.09.2017).

17. Meld. St. nr. 13 (2011–2012). Utdanning for velferd. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-13-20112012/id672836/ (downloaded 20.09.2017).

18. Magnusson J, Vrangbæk K, Saltman RB. Nordic health care systems. Recent reforms and current policy challenges. Open University Press. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series; 2009.

19. Fagerström L. (ed.). Avancerad klinisk sjuksköterska. Lund, Sverige: Studentlitteratur; 2011.

20. Fagerström L. Developing the scope of practice and education for advanced practice nurses in Finland. International Nursing Review 2009;56:269–72.

21. Hansen C, Hamric B. Reflection on the continuing evolution of advanced practice nursing. Nursing Outlook 2011;51:203–11.

22. Hutchinson M, East L, Stasa H, Jackson D. Deriving consensus on the characteristics of advanced practice nursing. Nurs Res. 2014;63:(2):116–28.

23. Millberg, LG. Akademisering av specialistsjuksköterskans utbildning i Sverige. Fakulteten för samhälls- och livsvetenskaper. Omvårdnad. Karlstad universitet, Sverige. 2012;56. Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:570330/FULLTEXT01.pdf(downloaded 02.10.2017).

24. Jeon Y, Lathinen P, Meretoja R, Leino-Kilpi H. Anesthesia nursing education in the Nordic countries: Literature review. Nurse Education Today 2015;35(5):680–8.

25. Skogsaas B. Praksisveilederes refleksjoner om akademisering av AIOK-videreutdanningene. Sykepleien Forskning 2016;11:1. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2016/02/praksisveilederes-refleksjoner-om-akademisering-av-spesialutdanningene(downloaded 20.09.2017).

26. Universitets- og høgskolerådet. Merverdi ved master i sykepleie. Rapport fra Nasjonal fagstrategisk enhet for utdanning og forskning innen helse- og sosialfag. Oslo. 2016. Available at: www.uhr.no/documents/Merverdi_master.pdf (downloaded 20.09.2017)

27. Konsmo T. Fokusgruppeintervju. Available at: http://www.helsebiblioteket.no/kvalitetsforbedring/brukermedvirkning/fokusgruppeintervju (downloaded 12.02.2015).

28. Morgan DL. The focus group guidebook. Portland State University, USA. Sage Publications Inc; 1998.

29. Marková I, Linell P, Grossen M, Orvig AS. Dialogue in focus groups. Exploring socially shared knowledge. London: Equinox; 2007.

30. Svennevig J. Språklig samhandling. Innføring i kommunikasjonsteori og diskursanalyse. Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk, Landslaget for norskundervisning; 2001.

31. Asmuss B, Steensig J (eds.). Introduktion. In: Samtalen på arbejde. København: Samfundslitteratur. 2003.

32. Lind M. Diskurstranskribsjon. En elementær innføring i teori og metode. Norskrift, 1995;1–24.

33. Braun B, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:(2):77–101.

34. Koselleck R. Erfaringsrom og forventningshorisont – to historiske kategorier. In: Nevers J, Olsen N. (eds.): Begreber, tid og erfaring. En tekstsamling. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag; 2007.

35. Hole G O, Brenna SJ, Graverholt B, Ciliska D, Nortvedt MW. Educating change agents: a qualitative descriptive study of graduates of a Master’s program in evidence-based practice. BMC Medical Education 2016;16:71.

Comments