How do nursing students learn anatomy, physiology and biochemistry (APB) with the aid of teaching assistants?

The teaching assistants were second-year students themselves, and used academic competence, social engagement and creative methods. This made it easier for the nursing students to learn complex academic material.

Background: A high fail rate and poor average examination grades for anatomy, physiology and biochemistry (APB) are cause for concern and raise the question of whether nursing students’ knowledge of science subjects is adequate. As a result, Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet – Pilestredet campus) employed teaching assistants to improve the teaching of APB in mandatory seminar groups. Together with an academic member of staff, they formed part of the research team that developed, implemented and evaluated a revised APB teaching programme based on near-peer teaching (NPT). We wanted to find out what it is about the teaching assistants and their teaching that helps nursing students to learn APB.

Objective: Acquire knowledge on how nursing students get help in learning APB from teaching assistants in mandatory seminar groups.

Method: In this study we analysed qualitative data from anonymous written feedback (n = 55) and three focus group interviews (n = 22) with first-year students in three seminar groups (N = 71) led by the six teaching assistants. The data were analysed with the aid of Graneheim and Lundman's qualitative data analysis.

Results: The nursing students found that tuition with the teaching assistants helped them to learn APB. Aspects of the teaching assistants that the students experienced as positive were that they 1) possessed knowledge of relevance for exams and enthusiasm for the subject, 2) understood the students and contributed to a good class environment, and 3) used enjoyable and creative methods. Learning was hindered by the fact that they spent too much time trying things out and did not coordinate their tuition with the lectures.

Conclusion: The teaching assistants’ combination of academic competence, social engagement and creative learning methods reduced the nursing students’ barriers to learning science and inspired them with a sense of ownership of APB. The teaching assistants created safe learning environments and decided pace and direction, which reduced the psychological barrier to learning complex academic material and increased the nursing students’ opportunity to make full use of their learning potential. Although the teaching assistants lacked pedagogical training and had not come very far in their own study programme, the study shows that they can be a resource that nursing programmes should use to meet the challenge of an unsatisfactory level of APB knowledge among nursing students.

The study investigates how nursing students get help in learning anatomy, physiology and biochemistry (APB) from teaching assistants through mandatory seminars. Science subjects such as APB occupy a central place in nurses’ training and practice of their profession, but many students struggle with the subject (1–3).

Although the teaching institution has mandatory APB seminars led by academic staff, the fail rate in APB in the national examinations is around 20 per cent, and the average grade is a D (4–6). To improve the teaching in mandatory seminars, six second-year students (teaching assistants) were engaged to develop, implement and evaluate a revised APB teaching programme.

Near-peer teaching

Near-peer teaching (NPT) is conducted by students who have come further in their studies than students at a lower level (7). In this article, the NPT is used for all teaching activities associated with the mandatory APB and nursing seminars.

NPT is a variant of peer-assisted learning (PAL). In contrast to conventional teaching, where academic staff with formal teaching qualifications lead the teaching, students at the same level (peers) are engaged to teach one another (8, 9). Based on social constructivism and an understanding of learning as “discovery”, the interplay between teacher and students and among students is crucial to the development of new knowledge (10).

NPT is further based on theory of social congruence, or similarity between teacher and learner (11). Similarity in age, status and language makes it easier to bring about conversations and interaction that lead to learning (8). Teaching assistants who have just learned the material themselves will also have a better understanding of what the students struggle with, and what they need to learn (12).

Studies from nursing and other health-related educations report positive effects from NPT in science subjects such as APB (13–16). Qualitative studies show that teaching assistants create safe learning environments (11), reduce the level of students’ anxiety and increase the satisfaction of both teachers and students (17). There is also evidence that the students identify with the teaching assistants and find it easier to ask questions (18).

Most NPT studies are limited to guidance in clinical procedures and are not used extensively in theoretical subjects (16). Most studies are qualitative, but some quantitative studies indicate that using teaching assistants in tuition helps nursing students in terms of motivation and understanding of APB (15), and yields the same or better exam results compared with those who are taught by academic staff (18, 19, 14).

Sociocultural learning theory

Sociocultural learning theory recognises that students have relevant knowledge which is necessary for learning new academic material (20).

The concept ‘zone of proximal development’ stresses that learning must be based on the individual’s existing knowledge (21), and that teachers and fellow students can function as scaffolding that makes it possible for students to reach out beyond what they know (10). In a good learning environment, students are integrated into social and academic fellowships that enable the individual to maximise their learning potential (22).

Acquiring academic knowledge entails developing a new vocabulary and integrating concepts that change one’s own perception of reality (21). Because the language is collective, it gives the individuals a common basis for thinking and reasoning. The fellowship with the teacher and fellow students thereby contributes to cognitive development and learning for the individual student (10).

Creating good learning environments that promote maximum learning outcomes for all students is demanding. Because of large student cohorts and few academic staff per student, universities have found it necessary to engage students as teaching assistants to enable them to meet the challenge (12, 13).

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gather data on how nursing students are helped to learn APB by teaching assistants in mandatory seminars.

Method

The study has a qualitative, explorative design. It is based on two qualitative datasets: anonymous written feedback from students (n = 55) and three focus group interviews after APB exams (n = 22). We chose to conduct focus group interviews because they provide a lot of information in a short period of time. We were able to investigate the participants’ subjective experience of taking part in APB tuition with teaching assistants (23–25).

The written feedback was not intended to form part of the data collected, but rather to be an evaluation by the students for the benefit of the teaching assistants, to enable them to make changes in the course of the seminar series. However, the feedback proved to contain valuable data that supplemented the focus group interviews, and it was therefore included. Flexibility and the use of multiple sources in order to achieve data saturation are features and strengths of qualitative studies (24).

The study administration put together seminar groups. This was done randomly, except for the deliberate distribution of men across all the study groups. Three of the in all 21 seminar groups in the cohort were drawn blind for the intervention (N = 71). Seven to eight students from each seminar group participated in the focus group interview.

The intervention

Six teaching assistants, two men and four women, were engaged to develop, implement and evaluate an intervention involving mandatory seminar groups in an attempt to help first-year students to learn APB. The teaching assistants, under the guidance of a project manager, made up the research group who planned and conducted the intervention and the research.

The selection criteria for the teaching assistants included having obtained an A or B grade in the APB exam. They also had to have demonstrated an ability to help other students (PAL) and to have had leadership experience, for example in sports or youth organisations. The teaching assistants were employed and received hourly wages for their work. In preparation, the teaching assistants went on a full-day course in pedagogics, learning theory and class leadership. They worked in pairs and prepared detailed teaching plans for each seminar group.

The research group held six meetings before and during the intervention. The primary goal was to improve APB teaching. On this basis the research group planned the seminars at which the teaching assistants would replace academic staff and implement and evaluate a revised APB and nursing teaching programme. The teaching assistants participated in the research work by planning, collecting data, transcribing, analysing and communicating the results.

Data collection

The interview guide for the focus group interviews contained six open-ended questions about themes such as satisfaction, expectations, motivation and preparation for exams. With this open-ended approach we wanted to pave the way for students to investigate together what it had been like to learn APB with the help of the teaching assistants. This enabled the teaching assistants who conducted the interviews to follow the process in the group and to ask follow-up questions as needed.

The interviews lasted about an hour, and the students had plenty to say. The interviews were conducted on campus by two of the teaching assistants who had not themselves taught the group they were interviewing. This was intended to make it easier for students to make critical remarks without directing them at the teaching assistants who had taught them. The interviews were recorded and transcribed by one of the teaching assistants who had attended the interview.

The written feedback was transferred to paper and provided answers to two open-ended questions:

- What aspects of the teaching do you think have been good?

- What aspects of the teaching do you think have not been good, or what could be improved?

Analysis

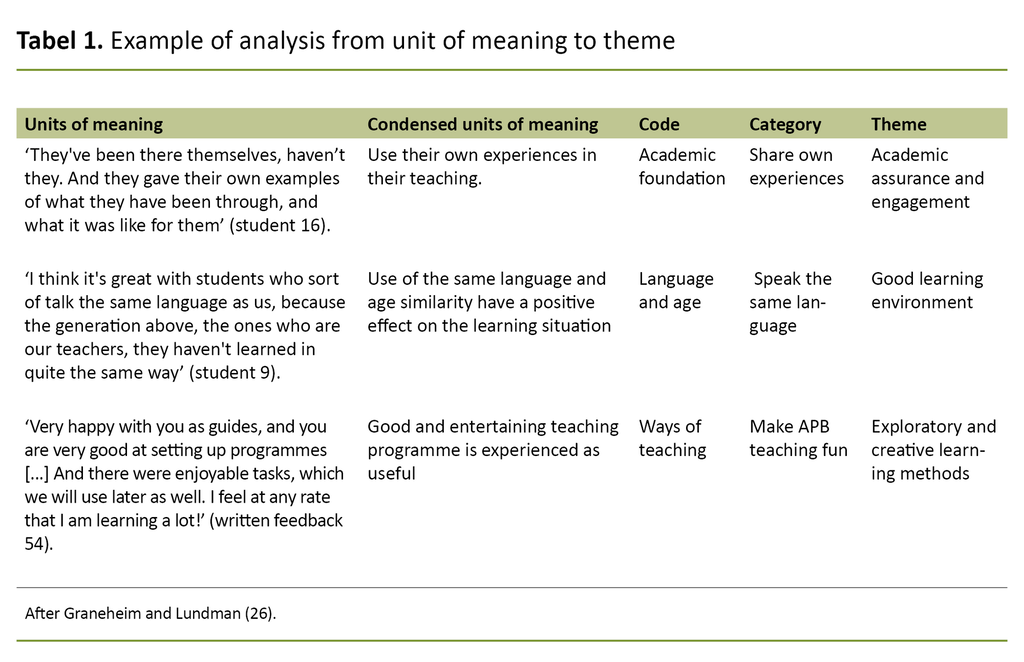

We used Graneheim and Lundman’s (26) qualitative content analysis to analyse the data. First, everyone in the research group reviewed the data in its entirety. The authors analysed the material from both the focus group interviews and the anonymous written feedback, and extracted relevant quotes (units of meaning).

We condensed the units of meaning, and then raised them to a higher level of abstraction by marking them with a code. Codes with similar content were sorted into categories. In the last part of the analysis, we raised the categories into three larger overarching themes. Then we identified common underlying meaning content for each theme.

We worked with codes, categories and themes and then presented this to the whole research group. They submitted input which we used to revise the analysis. This process was repeated until we reached consensus. Table 1 shows an illustration of the analytical process.

Ethical considerations

The students in the intervention group were informed that their seminar group had been drawn randomly, and that they could opt out of participating in the study at any time. A few expressed scepticism about participating, but no-one opted out. We obtained written informed consent from all students in the intervention group and all interviewees. The study has been approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference number 339743.

Results

Of the 71 students who participated in the intervention, 66 were women (93 per cent) and 5 men (7 per cent). Because of the uneven distribution in the intervention group compared with the whole 2017 cohort, in which 13 per cent were men, we included four men in the focus group interviews. As a result, 18 per cent of the 22 participants in the focus groups are men. The students’ ages varied from 19–32, with most being around 20-21 years old (Table 2).

Characteristics of teaching assistants who support teaching of APB

The main findings can be summed up under three themes: One is that the teaching assistants are academically confident and enthusiastic, the second is that they created a good learning atmosphere, and the third is that they used creative learning methods.

Academic assurance and enthusiasm

The nursing students described the teaching assistants as academically competent. They got help in working with the difficult topics. If the teaching assistants did not have the answer at hand, they worked with the students to find it.

The teaching assistants were felt to have a good understanding of the curriculum and detailed insight into APB: ‘The teaching assistants have been very clever. They know a lot about anatomy, and are very good at providing answers to all the things we have been uncertain about’, (written feedback 35).

The teaching assistants demonstrated academic enthusiasm and genuine interest in APB, which inspired the students and bolstered their belief that they too could succeed. They got help in sorting and prioritising and had confidence in the teaching assistants’ advice, both academic and with respect to how to work: ‘They've been there themselves, haven’t they? And they gave their own examples of what they have been through, and what it was like for them’ (student 16).

Good learning environment

The nursing students emphasised that the social aspect of the seminars was important for learning APB. One student said: ‘They pushed us to get to know one another better” (student 20), and maintained that this was important for learning such a tough subject.

‘You’re comfortable with the person you get to know, or the class you get to know. So you can ask about school things you are uncertain about; even if there is no study gathering that day, you aren’t afraid to send a message: “Hi, there's something I’m not sure about” (student 18).

The fact that the teaching assistants were of a similar age and were themselves students made it easy to ask about ‘everything’.

The fact that the teaching assistants were of a similar age and were themselves students made it easy to ask about ‘everything’ without being afraid of not being clever enough: ‘I think it's great with students who sort of talk the same language as us, because the generation above, the ones who are our teachers, haven't learned in quite the same way’ (student 9). The teaching assistants also participated in a joint Facebook group, where students were able to ask one another questions.

The nursing students found that the teaching assistants had insight into what they struggled with, and were able to relate to the students’ situation: ‘Great having students as guides. I feel you understand us better because you’re students yourselves. Anatomy study groups have been very good, because anatomy is both important and difficult’ (written feedback 32).

Creative learning methods

‘We learned in a way that was great fun and enjoyable’, wrote one student (written feedback 5). A lot of humour and laughter in the seminars helped to ‘make the gatherings fun’. The teaching assistants were creative, and invented competitions and games that capptured the students’ interest:

‘Now that we have got activated and involved in this [...] I find I learn so much more if I’m involved in doing it myself, not just hearing it, because then I think for myself and understand it in my own way, and can try and pass it on’ (student 11).

The students were encouraged to use many different sides of themselves to learn APB, such as singing and drawing.

The students were encouraged to use many different sides of themselves to learn APB, such as singing and drawing. The encouragement to use multiple teaching resources, and not just textbooks, was stressed as liberating and creating confidence – that the students were allowed to learn APB in a way that worked for them.

Challenges associated with using teaching assistants

The students singled out as challenging aspects of having teaching assistants that the programme could be too slack, and that the teaching assistants spent a lot of time on trial and error and asking the students what they wanted. Another point was that the topics they worked on in the seminars were not coordinated with their lectures. Students who had not prepared by doing their own reading therefore lacked the necessary preliminary knowledge for working in depth on themes in groups.

Discussion

In the following, we discuss the qualities of teaching assistants that we found helped to dismantle barriers to learning science and to increase students’ ability to tackle their aversion to learning difficult academic material, so that it was easier for nursing students to learn APB.

Help to dismantle barriers to science

Nursing students find APB more difficult to learn than other subjects (1, 4). APB are classified in nursing educations as ‘medical subjects’, a classification that is underpinned by the fact that the lecturers and textbook authors are often doctors (3). The absence of teachers with solid APB knowledge from their own profession makes it difficult for nursing students to develop ownership of and familiarity with the science subjects (2).

One clear finding of the study is that nursing students found the teaching assistants to be academically competent. They knew APB at a high enough level to be able to explain the details and relationships to the students and to guide them in the curriculum. In the teaching assistants, the nursing students met other nursing students who were going to become registered nurses like themselves. The teaching assistants were perceived as genuinely interested in science, and they put across the importance of learning APB in order to become a competent nurse.

One clear finding of the study is that nursing students found the teaching assistants to be academically competent.

‘They spoke the same language as us’, said several of them. Closeness in age and status may have made it easier to understand what the teaching assistants were explaining (9, 11).

Creative learning methods such as the “forehead game”, where students stuck anatomical terms onto the foreheads of fellow students and then reasoned their way to the right answers, created enthusiasm and familiarity with the concepts. The students got to investigate the material together and say the words themselves, and even draw on their own bodies and those of others. Learning methods that activate and engage the students encourage ownership and familiarity with the academic material (10).

The expression ‘they were us before’ can be understood as meaning that the teaching assistants appeared as competent ideals, something that was attainable also for the nursing students. They were living proof that nursing students can master APB at a high level.

At the same time, the teaching assistants came across as ‘humble’ and ordinary students, whom the nursing students could identify with. Being able to identify with the instructor can lead to identifying with the subject (13, 19, 22). In this way the teaching assistants may have broken down some of the barriers to science and paved the way for the nursing students to be able to experience APB as ‘their subject’, thereby making learning it more achievable.

Help in tackling the psychological barrier to learning difficult academic material

Learning new things is challenging, because it's a matter of stepping out of the known and stretching towards something new and foreign (21). In a subject such as APB, with many unfamiliar terms and relationships that are not immediately comprehensible, part of the challenge is tackling the insecurity associated with not understanding and not having an overview. The psychological barrier and insecurity lead to many nursing students lowering their ambitions and giving up learning APB more than superficially (3).

The nursing students described the seminars with the teaching assistants as ‘fun’. Creative learning activities, with elements of games, song and competitions, stood out in the findings. The students described a youthful form of communication in the teaching, with a lot of laughter and playfulness. Having fun while one learns reduces anxiety and negative pressure (10, 111).

The teaching assistants had the social milieu in the class constantly in mind. The students reflected over this, and pointed out that the teaching assistants ‘pushed’ them to get to know one another, and that this pressure was perceived as positive.

The teaching assistants had the social milieu in the class constantly in mind.

The students worked a lot in small groups. The formation of new small groups at each seminar led to them all getting to know everybody. Many of the students also held study-related gatherings outside the seminars. One student described the sense of community in their seminar group as ‘we took up a whole row in the auditorium’. Social support and recognition make the students feel safe and release energy for concentrating and using their capacity to investigate the unknown (9, 21).

In a secure learning atmosphere, students can test out reasonings and present interpretations that are incomplete, and still not fully comprehended (7, 13, 21). Fellow students can function as ‘scaffolding’ (10) for one another, and support each other in getting over the psychological barrier to learning difficult material, until they achieve a breakthrough to new insight and understanding.

The students also found the teaching assistants supportive, both in the seminars and in the Facebook group, where they gave advice to and encouraged the students. Because the teaching assistants were students themselves, and had recently experienced the challenges of learning the academic material, they were able to understand what the students were asking for help with (12, 18).

At the same time, the teaching assistants applied pressure to the students. They made it clear what was required to pass exams, and set up programmes that required the students to work hard and prioritise APB. The students had to explain concepts and relationships to their fellow students, both in small groups and at the board. A mock exam was also arranged. Some found this fun and stimulating and that it helped them to work in a focused way and obtain good grades. Others found it too demanding, and not being able to keep up was demotivating.

Finding the balance between support and reassurance on the one hand and pace and direction on the other is a key principle of sociocultural learning theory (10, 21). There is reason to believe that the approaches and qualities of the teaching assistants helped to reduce negative anxiety and thereby helped the nursing students to make better use of their learning potential.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strength of this study is that teaching assistants, who were themselves nursing students, took part in identifying problems and implemented an intervention. The teaching assistants planned and conducted interviews. This is an advantage, because they are on an equal footing with the informants and speak the same language.

The challenge is that they lacked training in conducting focus group interviews, and thus missed information that might have been picked up by a more experienced moderator (24).

Conclusion

The teaching assistants’ combination of academic competence, social engagement and creative learning methods reduced the nursing students’ barriers to learning science and gave them ownership of APB. The teaching assistants created safe learning environments and set pace and direction, which helped to reduce the psychological barrier to learning complex academic material and improved the nursing students’ opportunity to exploit their learning potential.

Although the teaching assistants lacked pedagogical training, and had only come a short way in their own studies, the study showed that they can be a resource that the nursing educations should use to meet the challenge of a low level of APB knowledge among nursing students.

The participants in the research group and invaluable contributors to the article in the form of intervention and collection, processing and analysis of our data were:

- Melissa Lindfield Solberg, registered nurse, Akershus University Hospital Trust

- Hanna Kvinge Augustin, registered nurse, Oslo University Hospital Trust

- Lars Peder Kolås Henriksen, registered nurse, Oslo University Hospital Trust.

The authors also wish to thank the Institute of Nursing and Health Promotion at OsloMet – Pilestredet for help in setting up the project and for financial support.

References

1. McVicar A, Andrew S, Kemble R. The ‘bioscience problem’ for nursing students: an integrative review of published evaluations of year 1 bioscience, and proposed directions for curriculum development. Nurse Educ Today. 2015 mar.;35(3):500–9.

2. Johnston A, Hamill J, Barton MJ, Baldwin S, Percival J, Williams-Pritchard G, et al. Student learning styles in anatomy and physiology courses: meeting the needs of nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015 nov.;15(6):415–20.

3. Craft J, Christensen M, Wirihana L. Advancing student nurse knowledge of the biomedical science: a mixed method study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017 Oct.;48(1):114–9.

4. Bergsagel I. Høy strykprosent etter omdiskutert anatomieksamen. Sykepleien 20.01.2021. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/2021/01/hoy-strykprosent-etter-omdiskutert-anatomieksamen (downloaded 19.04.2021).

5. Dolonen KA. Sensuren har falt i anatomi, fysiologi og biokjemi: Her er resultatene. Sykepleien 28.01.2019. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/2019/01/sensuren-har-falt-i-anatomi-fysiologi-og-biokjemi-her-er-resultatene (downloaded 27.01.2021).

6. Schei A. Færre sykepleiestudenter strøk. Sjekk oversikt for studiestedene. Khrono 22.01.2020. Available at: https://khrono.no/faerre-sykepleiestudenter-strok-sjekk-oversikt-for-studiestedene/436100 (downloaded 27.01.2021).

7. Topping KJ. The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: a typology and review of the literature. Higher Education. 1996 Oct.;32(3):321–45.

8. Topping KJ, Ehly S. Peer-assisted learning. New York: Routledge; 1998.

9. Stone R, Cooper S, Cant R. The value of peer learning in undergraduate nursing education: a systematic review. ISRN Nursing. 2013 Apr.;2013:930901.

10. Bruner J. Utdanningskultur og læring. Oslo: Ad Notam Gyldendal; 1997.

11. Lockspeiser T, O’Sullivan P, Teherani A, Muller J. Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2008 Aug.;13(3):361–73.

12. Lorås M. From teaching assistants to learning assistants – lessons learned from learning assistant training at Excited. In: Solbjørg O-K, eds. Læringsfestivalen 2020. Trondheim: NTNU;2020;4(1).

13. Irvine S, Williams B, McKenna L. Near-peer teaching in undergraduate nurse education: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018 Nov.;70:60–8.

14. Williams B, Reddy P. Does peer-assisted learning improve academic performance? A scoping review. Nurse Educ Today. 2016 Jul.;42:23–9.

15. Meyer M, Haukland E, Glomsås M, Snoen H, Tveiten S. Studentassistenter bidro til læring i anatomi, fysiologi og biokjemi. Sykepleien Forskning. 2019;14(79469):(e-79469). DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2019.79469

16. Herrmann-Werner A, Gramer R, Erschens R, Nikendei C, Wosnik A, Griewatz J, et al. Peer-assisted learning in undergraduate medical education: an overview. Zeitschrift fuer Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitaet im Gesundheitswesen. 2016 Apr.; 121:74–81.

17. Secomb J. A systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. J. Clin Nurs.2008 Mar.;17(6):703–16.

18. Cate OT, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007 Sep.; 29(6):546–52.

19. Brannagan KB, Dellinger A, Thomas J, Mitchell D, Lewis-Trabeaux S, Dupre S. Impact of peer teaching on nursing students: perceptions of learning environment, self-efficacy, and knowledge. Nurse Educ Today. 2012 Dec.;33(11):1440–7.

20. Vygotsky LS. Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1978.

21. Vygotskij LS. Tenkning og tale. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2001.

22. Wang L. Sociocultural learning theories and information literacy teaching activities in higher education. Reference & User Services Quarterly. 2007;47(2):149–58.

23. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; 2018.

24. Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2012.

25. Moen K, Middelthon A-L. Qualitative research methods. In: Laake P, Benestad HB, Olsen BR, eds. Research in medical and biological sciences: from planning and preparation to grant application and publication. Academic Press; 2015. pp. 321–78.

26. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12.

Comments