Nurse managers’ importance for the learning environment of student nurses in nursing homes

By adopting a new supervision model, nurse managers acquired more positive attitudes towards students and started paying more attention to nursing issues.

Background: Nursing education and the field of practice are undergoing change, as are the requirements for what and how nursing students should learn in clinical practice. First year nursing students’ evaluation of their clinical placement at nursing homes revealed a need to examine the learning environment in nursing homes more closely.

Objective: To describe and explore the influence of nurse managers in order to develop nursing students’ learning environment in nursing homes and to trial a new group-based supervision model.

Method: A descriptive and exploratory design was employed whereby qualitative data were collected through research interviews with five nurse managers in three nursing homes. The purpose was to trial a new supervision model.

Results: Even though all the wards that participated in this collaborative project between nursing education and clinical placements were represented in the steering or project group, the nurse managers had varying knowledge and preparation in respect of the new supervision model prior to the students’ period of clinical practice. This had a bearing on information about the new supervision model and its underpinning. The nurse managers had different roles in the work to pave the way for the supervision model, and attitudes towards the students varied. The supervision model promoted greater professional commitment in the wards and a more positive attitude towards being a contact nurse.

Conclusion: The nurse managers proved to play an important role in efforts to develop nursing students’ learning environment in nursing homes. Clearer parameters, structure, roles and responsibilities in the supervision model helped ward staff to acquire greater understanding of the supervision responsibility. The model with more nurses and students resulted in more professional discussions in the wards.

According to the National Framework Curriculum for the Bachelor Degree in Nursing, clinical practice and skills training constitute half of the course of studies: 90 credit points (1). The learning environment in clinical placements is therefore of major importance in the education of nurses. Since nursing education and the field of practice are undergoing change, requirements as to what and how students should learn are also changing.

In order to educate independent and critical nurses, there are higher requirements for evidence-based theory and practice, active, digital learning methods, simulations, critical thinking and reflection. Previous supervision models were often based on a 1:1 relationship between the contact nurse and the student, in line with the Master-Apprentice model. Today, the increasing number of students, higher requirements for efficiency and more emphasis on reflection account for the need for new supervision models.

Different supervision models

This project, which trials a new supervision model, is similar to two other models: the SVIP model (strengthening supervision in practice) and the Peer Learning-model. The SVIP-model has been tested in nursing homes and in the community nursing service (2).

The main elements consist of supervision at two levels: daily supervisors supervise students placed in practice and strengthen their own supervisory skills through group supervision from the educational institution. The evaluation of the SVIP model shows good results as well as potential areas for improvement (3).

In Sweden, the Peer Learning model was adopted as an alternative model. Nursing students worked in pairs in a learning community with supervisors, where the point of departure was that learning is constructed through social interaction in cooperation with significant others (4).

The results showed that many students gained better cognitive skills, self-confidence, autonomy, clinical skills, and a greater ability to argue and reason systematically. Meanwhile, negative effects arose if the students did not work well together. Rivalry could also take place when the students tried to gain the supervisor’s attention.

Several studies have referred to positive experiences gained from group practice, asserting that this provides good opportunities for learning and support in the student group. Bourgeois et al. (5) described how a case-based innovative learning model supported student learning and gave better learning opportunities in clinical teaching. Ekebergh (6) demonstrated that a reflective group model taught students to reflect more systematically by means of realistic learning situations.

These supervision models reflect a situated view of learning, which means that learning is regarded as a basic social process, closely linked to the context and shared among people, and that it takes place through participation in social practice (7).

Background of the project

The background of the project was that students’ course evaluations from the former Telemark University College had revealed over time a need to investigate the learning environment in nursing homes. Telemark University College and three nursing homes therefore started a collaborative project to quality assure and develop the students’ learning environment (8).

As part of the project, a new group-based supervision model was to be adopted. This model entailed that each ward accepted more students than before, going from one to two or three students. The students were to be assigned a contact nurse but also had other supervisors.

A 20 percent position as student coordinator at each nursing home was funded through the project. The student coordinators at each nursing home had overarching responsibility for the students’ clinical placement period, in close collaboration with the nurse managers, contact nurses and other supervisors. They also acted as contact persons between the nursing homes and the university college in the project period.

Objective

Data were collected from several target groups: students, contact nurses and supervisors, student coordinators, teachers and nurse managers. The nurse managers were interviewed because they played a key role in the work of organising the project and developing the students’ learning environment.

This article contains data based on interviews with the nurse managers. The objective is to describe and explore the influence of the nurse managers in the development of the nursing students’ learning environment and to trial a group-based supervision model.

Method

This study has a descriptive and exploratory design, using the collection of qualitative data as a method. The testing of a new supervision model also included an action-oriented approach. The contact nurses and student coordinators at the nursing homes implemented the supervision model.

Sample

The sample in the project consisted of five nurse managers from three nursing homes. Telemark University College recruited informants via the heads of unit at the nursing homes, who participated in the project’s steering group. The interviews took place in a private room at each nursing home and lasted approximately one and a half hours. All the interviews were recorded, transcribed, analysed and processed by the author.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted individually, with one exception where two informants were interviewed at the same time in order to ensure that the data collection was carried out within the given period of time. A semi-structured interview guide consisting of ten questions was used for the interviews. Six questions were concerned with management and four were linked to the students’ learning environment and experiences with the group supervision model.

Data analysis

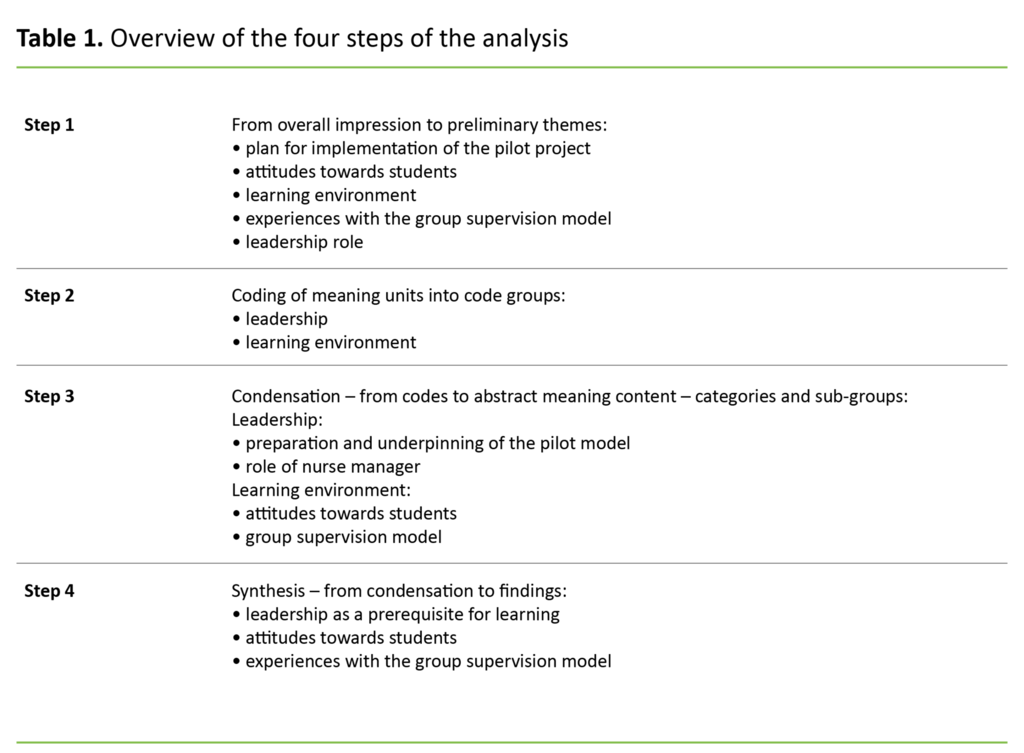

Systematic text condensation (STC), which is a pragmatic method for a thematic cross-cutting analysis of qualitative data, was used (9). The analysis was conducted in line with the four steps of the method: 1) from overall impression to preliminary themes, 2) coding of meaning units – code groups, 3) condensation – from codes to abstract meaning content and sub-groups and 4) synthesis – from condensation to findings.

The analysis was an inductive process with a forward and backward analysis process between the various steps. At the final stage of the analysis, the results were summarised under three themes (Table 1):

- Management as a prerequisite for learning

- Attitudes towards students

- Experiences of the supervision model

Validity and reliability

The interview guide was prepared in cooperation with the project group and was submitted to the steering group prior to the data collection. The project group consisted of contact nurses, student coordinators and a representative of Telemark University College, while the steering group consisted of unit heads from each nursing home, a head of department and a representative of Telemark University College.

To strengthen validity, test interviews were carried out with two external subjects to ensure that the questions were understood correctly and could produce valid data (9). The author carried out all the steps in the data collection: the interviews, subsequent notes, transcription, readthrough and the analysis.

Although all the steps in the research process were documented, threats to reliability are that the author alone analysed the data (10), and that two informants were interviewed at the same time. The author had no ties to the informants outside the project. With a sample of five informants, the results are not transferrable beyond this sample.

Ethical considerations

The heads of the three nursing homes gave the University College access to the research field. The informants were given written and oral information about the study as well as being informed that participation in the interviews was voluntary and that the data would be treated confidentially and presented in an anonymous form. The University College was responsible for collecting, processing and storing the data in line with research ethics requirements.

The study was not reported to the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) or the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC) because no personal data were involved, and the result of NSD’s Notification Test showed that the study was not subject to notification according to the rules then applicable.

Results

The results are presented in three sub-sections, in line with step 4 of the analysis (Table 1):

- Management as a prerequisite for learning

- Attitudes towards students

- Experiences of the supervision model

- Management as a prerequisite for learning

Nurse managers showed different degrees of preparation in terms of implementing the project and trialling a new supervision model, even though all wards had participated either in the project’s steering or project group. The preparations had mostly been made via oral communication between the student coordinators and nurse managers, as well as with the institution’s chief executive in most cases. There were no written plans.

Information about the project and its underpinning differed in the various wards. Some nurse managers had held information meetings for the entire ward, while others had informed staff on an ongoing basis. Several informants were of the opinion that the nursing home had not been well enough prepared before the arrival of the students.

The nurse managers felt that it had been important to use their leadership to facilitate student supervision and they were acutely aware of the responsibility. However, there were variations in how they facilitated the supervision.

Several nurse managers had given the nurses more time to supervise the students by taking over tasks for them or delegating tasks to others. Others had passed on much of the responsibility for the students to the student coordinator and the nurses, and had less interaction with the students than was normally the case.

Several felt that they could contribute more when it came to making provision for this, which they expressed as follows: ‘As a manager, I think that I have more to learn here. I’ve freed up time for the supervisors and passed on some responsibility to them and said that they must report back to me if they need more time. But I believe I can step in and manage more without taking over responsibility.’

In some wards, it was difficult for nurse managers to secure understanding in the staff group of the supervision responsibility vis-à-vis the students, and they focused on this the whole time. None of the nurse managers had dedicated forums for developing the learning environment, but ward and staff meetings and reflection were arenas that were used. They had not all been equally good at talking about the presence of students in the department or had only discussed this in the nursing group.

The nurse managers regarded it as important for the students that the nurses had good supervisory skills and were motivated, and they made provision for such competence. They perceived that most nurses wanted to develop their supervisory skills and that their motivation had increased further after attending supervision courses. Nevertheless, the managers had ordered some contact nurses to take supervision courses.

Attitudes towards students

The nurse managers believed that it was very important that they were positive to the students and set a norm for this in the ward. Meanwhile, their attitudes were nuanced. On the one hand, there were managers who regarded students as a resource and support in the ward and believed that it was stimulating for everyone to have students present. The nurse managers showed interest in the students’ learning and included them in the ward’s working environment.

On the other hand, there were managers who had less interaction with the students than before, and who held the view that they had got off lightly this time. Students were also described as a burden for the nurses. Moreover, some nurse managers pointed out that even though the manager was positive to the students, this did not necessarily mean that the nurses were, and it had not always been a positive experience to have students in the ward.

This did not only concern negative attitudes towards students but also scarcity of time and resources to look after them properly. Some nurse managers had contact nurses who were basically negatively inclined towards students. Then the manager had to intervene in order to ensure that the nurses took responsibility and changed their negative attitudes:

‘If you have a coordinator [as in the project], then you have someone who basically wants to have students, you don’t have this as an additional job. Experience over the years shows that it’s very random and differs for the students. Of course, this has something to do with the contact nurse, but often management set a norm for what it’s like to have students.’

The nurse managers had organised the period of practice so that the contact nurses had most time for student supervision at the start, but there was some variation in how students were followed up later.

One of the managers expressed it as follows: ‘I consciously make use of the students, they are to work here but they are not to be exploited. I’m conscious that the students should not accompany the same nurses on each shift but observe different ways of doing things. And also spare the contact nurses from always having a hanger-on.’

The nurse managers were intent on ensuring that the students should have the best possible learning experience in clinical practice, and emphasised nurse coverage as the most important factor when deciding how many students they could accept.

Experiences with the supervision model

In general, the nurse managers had positive experiences with the supervision model and wanted to continue with it. They pointed out that they had acquired greater understanding of supervisory responsibility in the project, even though it could still be difficult. They believed that this was linked to the fact that the supervision model provided more structure and system. Roles and responsibilities were clearer, and more staff had been involved with the students and seen their need for supervision.

The managers had also experienced that the students did not feel so alone in their role, and that it was important to adapt the learning situation to both students when they worked in pairs. The following quote reflects these experiences:

‘There’s maybe been a change here, the students have had more supervisors and the staff has related more to the students, because they have functioned better, they’ve worked more independently than they’ve done before. They haven’t just tailed after one nurse.’

The nurse managers were of the opinion that the role of student coordinator was essential for the positive experiences of the supervision model; it led to a fairer practice for the students and was a big help for them as managers. The nurse managers had also found that the supervision model led to more discussion and focus on nursing issues in the wards.

The students had asked more questions about patient situations than before, and both the nurses themselves, and the nurses and students had more discussions relating to the nursing profession. One informant thought this a big change because there had been almost no discipline-related discussions over the years. The following quote sums up the managers’ experiences of the supervision model:

‘I see it as the future, more contact nurses and more students. I see it as a much better learning arena. More sound professionally, more discipline-related topics, more professional focus when there are several who can give their evaluation because then they start to talk about nursing matters. It becomes more important. As the only contact nurse, you can keep out of sight, but you can’t do that when there are more of you. Everyone talks to each other, the students as well, so you benefit professionally.’

One of the nurse managers believed that the greatest professional benefit of the supervision model was that being a contact nurse had become more positive.

Discussion

Plan and underpin student supervision

The results showed that the managers’ preparations, underpinning and role in testing the new supervision model differed, as did their attitudes towards student supervision and their arrangements for this. Their experiences with the supervision model were positive, particularly the fact that the nursing matters received more attention and that it had become more positive to be a contact nurse.

Management studies show that the success criteria for change processes and complex work processes are that senior management take the lead and underpin changes from the top down (11, 12).

This study shows that the nurse managers had planned and underpinned the supervision model in different ways, and the role of manager differed. The introduction of the SVIP model (13) indicated that it was important that nurse managers assumed responsibility and underpinned the model in advance, and that good planning and organisation of the model were key prerequisites for the nurses’ ability to carry out supervision.

Several nurse managers in this study were of the opinion that they had not prepared and underpinned the supervision model adequately beforehand. Nevertheless, they felt that they had gained greater understanding of supervisory responsibilities in the ward than previously. This may indicate that preparations for the students’ period of practice were better, however, in the collaborative project.

Other factors that promoted greater understanding of students’ supervision needs were that more people participated in the supervision and the manner in which managers showed involvement with the nurses and the students’ learning environment.

Clear leadership – attitudes and actions

The evaluation of the SVIP model showed that many nurses thought the nurse managers were invisible and felt that they had the responsibility alone (13). Jebsen (12) says the following about leadership: ‘It is all about relations.’ By this he means that trust, understanding, engagement and willingness to create, perform and produce are formed in relations, and that it is the manager’s responsibility to create social practices that promote development and change.

It is conceivable that nurse managers could gain more understanding of supervisory responsibility by establishing dedicated forums in the ward where staff could discuss and develop the learning environment generally and develop it for the students in particular. The nurse managers’ perceptions that this supervision model contributed to more equal conditions for students’ learning because of clear parameters, structure and responsibility constitute key factors in efforts to develop new supervision models.

Managers are important role models for all employees, both regarding attitudes and actions, and they must highlight visions and changes in the ward. The nurse managers in this study were conscious of their own attitudes towards students and worked to improve attitude-building in the wards. Nonetheless, nuances existed that may have affected the students’ learning environment differently.

Studies have shown that nurse managers’ attitudes towards supervising students were crucial for how the supervision was integrated into the learning environment (2). Studies have also shown that the students’ learning environment was linked to the ward’s pedagogical atmosphere, supervisory relations, ward management and the conditions for practicing nursing (14).

Birks (15) concluded that the preparations, sequencing and consistency of the placement institution were decisive factors for ensuring good learning opportunities for students, but the most significant finding was that the students needed to feel they were part of a team in the ward to acquire the best possible learning outcome.

In this study, all the managers were concerned that the students should learn as much as possible during their placement and expressed a situated view of learning (7). However, there is reason to believe that attitudes towards students and the way in which managers included them in the ward impacted significantly on students’ learning.

The positive experiences of the nurse managers with the supervision model and their wish that this should be continued are in step with the range of positive experiences of group-based supervision models from similar projects (2–6). It was surprising that this model promoted professional development and a more positive attitude towards being a contact nurse, but there was also a considerable need for attitude-building vis-à-vis the students.

Professional leadership

The integration of the SVIP model showed that nurse managers must be more than administrators, and that professional leadership and development must be key areas for improving the quality of nursing (13, 16). The quality of nursing affects the students’ learning. According to Ingstad (17), an increasing number of tasks have been imposed on nurse managers and nurses at nursing homes, as well as higher requirements in terms of efficiency. This may lead to downgrading professional leadership in favour of efficiency requirements, and to leaders becoming more invisible.

Nurse managers in this study said that the student coordinators had been a great help for them, and the discipline-related discussions that had taken place in the ward had been beneficial. Both professional development and attitude-building are clear management tasks, and findings in these areas indicate that it is important for the students’ learning environment that the nurse managers devote considerable attention to these tasks.

Joint responsibility for students’ learning environment

Nursing education and the field of practice have joint responsibility for developing the students’ clinical learning environment, and the new regulations on a joint framework plan for health and social care education that will enter into force in the 2020/2021 academic year will ensure that nursing education is better adapted to the future (18).

Niederhauser et al. (19) demonstrated that more cooperation between nursing education and the field of practice reduced the compartmentalisation of the two fields and created joint visions for developing clinical learning for nursing students. This study was based on a creative collaborative project between nursing education and three nursing homes and revealed that nurse managers by virtue of their role exercised considerable influence on the nursing students’ learning environment.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Nursing education and the field of practice spend considerable resources on the supervision of nursing students, and many studies focus on the role of contact nurse, student or teacher. This study shows that the role of nurse manager also influences the students’ learning environment.

The sample was small and provided limited insight into the topic. A broad mapping of how nurse managers influence the learning environment of nursing students can elucidate the topic more broadly from several aspects. This is a good point of departure for further development of the students’ learning environment in nursing homes.

Conclusion

The objective of the study was to describe and explore the importance of nurse managers in respect of developing the learning environment of nursing students in nursing homes, and to trial a new group-based supervision model. The supervision model was based on experiences of similar projects.

Nurse managers proved to play an important role in planning, underpinning and organising the supervision model, and helped to put in place positive attitudes towards students in the wards. Surprisingly, the supervision model contributed to more attention being paid to nursing issues and to more positive attitudes towards being a contact nurse.

References

1. Rammeplan for sykepleierutdanning. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2008. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/vedlegg/uh/rammeplaner/helse/rammeplan_sykepleierutdanning_08.pdf(downloaded 21.06.2018).

2. Bergseth WB, Solvik E, Engelien RI, Larsen ØM, Sønsteby SN, Struksnes S, et al. Styrket veiledning i sykepleierutdanningens praksisperioder. Vård i Norden. 2013;33(1):56–60.

3. Sønsteby SN, Engelien RI, Johansson IS. Veiledningsmodell for sykepleierstudenter i sykehjem – en evalueringsstudie. Vård i Norden. 2008;28(3):42–5.

4. Stenberg M, Carlson E. Swedish student nurses’ perception of peer learning as an educational model during clinical practice in a hospital setting – an evaluation study. BMC Nursing Open Access. 2015;14(48):1–7.

5. Bourgeois S, Drayton N, Brown AM. An innovative model of supportive clinical teaching and learning for undergraduate nursing students: the cluster model. Nurse Education in Practice. 2011;11(2):114–8.

6. Ekebergh MA. A learning model for nursing students during clinical studies. Nurse Education in Practice. 2011;11(6):384–9.

7. Øhra M. Digitale ferdigheter. Sosiokulturelt læringsperspektiv. Behaviorisme – konstruksjonisme – sosiokulturelt læringsperspektiv. Available at: http://www.digitalferdighet.no/metodikk/laeringsteorier(downloaded 01.06.2018).

8. Aase E. Kvalitetssikring og utvikling av kliniske studier for sykepleiestudenter i sykehjem. Et samarbeidsprosjekt mellom Porsgrunn kommune og Høgskolen i Telemark. Porsgrunn: Telemark Open Research Archive, TEORA; 2013. Project report.

9. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

10. Kvale S. InterViews. An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. 1. ed. London, New Delhi: Sage; 1996.

11. Aase E. Undervisningssykehjem – funky sykehjem? Norsk tidsskrift for sykepleieforskning. 2003;5(4):244–59.

12. Jebsen CH. Relasjonell koordinering – fremmer kvalitet og effektivitet i komplekse arbeidsprosesser. Scandinavian Journal of Organizational Psychology. 2015;7(2):13–6.

13. Sønsteby SN, Engelien RI, Arvidsson B. Mellom idealer og realiteter – Integrering av gruppeveiledningsmodellen SVIP i sykehjem. Nordisk sygeplejeforskning. 2013;3(02):130–8.

14. Papastavrou E, Dimitriadou M, Tsangari H, Andreau C. Nursing students’ satisfaction of the clinical learning environment: a research study. BMC Nurs. 2016;15(44):1–10.

15. Birks M, Bagley T, Park T, Burkot C, Mills J. The impact of clinical placement model on learning in nursing: a descriptive exploratory study. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2017;34(3):17–23.

16. Foss B. Faglige verdier som grunnlag for ledelse. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2009/03/faglige-verdier-som-grunnlag-ledelse(downloaded 30.11.2018).

17. Ingstad K. Arbeidsforhold ved norske sykehjem – idealer og realiteter. Vård i Norden. 2010;30(2):14–7.

18. Forskrift om felles rammeplan for helse- og sosialfagutdanninger. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2017. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/utdanningar-for-framtida/id2569698/(downloaded 30.11.2018).

19. Niederhauser V, Schoessler M, Gubrud-Howe PM, Magnussen L, Codier E. Creating innovative models of clinical nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2012;51(11):603–8.

Comments