Language use and patterns in nursing records. A discourse analytical approach

A care discourse, aimed at the patient’s needs, was prominent in the evaluation and assessment notes. The treatment plans reflected a problem-focused discourse, where only problems were recorded.

Background: Historically, registered nurses have entered information in patient records as free text. Health policy guidelines issued in 1996 provide for standardised terminology in nursing records with a view to improving the quality of patient care and enhancing coordination and continuity in nursing. There are few systematic studies of how language is used in nursing records: what is emphasised, how the written discourse works, and what potential patterns can be identified in the documentation.

Objective: The study examines language use and patterns in treatment plans and evaluation and assessment notes as well as their limitations and possibilities. The study seeks to contribute to reflections on the main patterns and associations in the written discourse.

Method: In the study, we examine the nursing records for ten patients in an intensive care unit. The study has a qualitative design, and discourse analysis is used as part of a methodological and analytical approach.

Results: Two prominent discourses, each with a different emphasis, were identified: 1) A care discourse is expressed as narrative text in the evaluation and assessment notes. Here, the starting point is the patient’s basic needs. The care discourse is aimed at fostering the patient’s well-being, welfare and ability to cope in the relevant situation, and consists of descriptive free text, where words and terms are linked to the context on which they are contingent. 2) A problem-focused discourse was identified in the treatment plan, which entails formalised expressions, where words and terms are taken from the NANDA and NIC classification systems. The nursing records were in keeping with the problem orientation of the nursing process and describe a plan for treating illness, and the narrative text was of a more colloquial nature. The analysis shows how the two discourses relate to and complement each other.

Conclusion: The discourses have two different starting points. The care discourse is characterised by a comprehensive review and a more literary narrative in which free text is used to describe a care-oriented approach, whereas the problem-focused discourse focuses on goals and interventions based on problems identified. These two discourses largely occur in parallel and do not complement each other to any great extent. The study shows that the care discourse seems to play an independent and hegemonic role in the nursing records.

Registered nurses (RNs) have a long tradition of describing and documenting their own activities. The tradition started with narrative text in the 19th century and continues to this day (1)

Sharing, exchanging and summarising such documentation and using it for different purposes have proven to be a challenge. The possibilities have therefore been limited for obtaining an overview of the patient’s nursing needs and of what nursing care is currently being provided or has been provided (2).

The National Health and Hospital Plan (2015–2016) points to the need for more systematic patient follow-up (3). The National E-health Action Plan (2017–2022) states that a common code system and harmonised terminology for nursing records is necessary to support the development of e-health solutions (4).

The nursing process has a problem-solving structure that has contributed to systematisation and served as a guide for what is to be documented. The nursing process should culminate in a treatment plan that reflects and evaluates the nursing care provided. The phases of the nursing process have provided a professional structure for documentation and stimulated the development of classification systems in nursing (1, 5).

Different classification methods have been tested

Since the 1970s, various methods for systematising and classifying nursing phenomena have been tested. Classification systems are designed to create a common language with uniform definitions of nursing. They focus on different aspects of practice, and none of them are considered exhaustive (5).

In Norway, the classification systems North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) and the Nursing Intervention Classification (NIC), which are implemented in the DIPS patient record system, are used in the specialist health service.

The development of NANDA started in 1973. This classification system, which covers the diagnostic part of the nursing process, consists of a selection of standardised nursing diagnoses. NIC, which was established in 1992, contains nursing interventions in which nursing measures and actions are named. Both classification systems were translated to Norwegian in 2002 (6, 7).

Objective of the study

The purpose of this article is to examine the language use and patterns in treatment plans and evaluation and assessment notes in documented health care at an intensive care unit that uses these classification systems.

In doing so, we sought to contribute to reflections on what is emphasised, and which associations are established in the documentation. The research question was as follows:

What discourses are identified in the nursing records in an intensive care unit, and how do these discourses relate to each other?

Background for the study

For the study, we performed systematic searches in the databases PubMed and CINAHL. The key area was to examine nursing records, and given the discourse theoretical perspective, the relationship between free text and the use of standardised language was pivotal. We systematised this in a PICO form (Figure 1).

However, we found few international studies, and no Norwegian studies, that had examined the linguistic aspects of nursing records or identified which discourses emerge.

Several studies have highlighted the potential of classification systems to improve the quality of nursing records, and to strengthen nursing research and education (8, 9).

The classification systems consist of terms that can be used to describe individual, family-oriented or societal responses to potential or actual health problems and life processes (10).

Studies show that the terminology from NANDA diagnoses and NIC interventions can be used to describe the patient’s problems and nursing-relevant measures across different specialties (11–14).

However, other studies show that patients’ unique reactions, experiences and emotions in critical illness are not reflected in the classification systems, and that the RNs combine free text and standardised words and terms to describe the patient’s health situation (15–17).

Despite a growing focus on RNs’ contribution to patient outcomes, criticism is levelled at the classification systems for being a standardisation mechanism aimed at prioritising an instrumental approach (18–20).

The results from the literature review show large variations in when the studies were performed and the findings made, and the results are difficult to interpret. It is therefore interesting to study nursing records in a discourse analytical perspective because it enables the study of language use and patterns in the documentation, where free text descriptions are at odds with nursing terminology.

Ethical considerations

In discourse analysis, it is the text itself and the use of language that are the core focus. This study uses anonymised data and is not subject to notification to the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC) or the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD).

The project was approved by the departmental management in the unit where the data was collected. The Data Protection Officer at the relevant hospital was involved in the collection process.

Method

The data material was made up of nursing records for patients who were admitted to an intensive care unit. We chose the intensive care unit because the RN here continuously monitors the patient, and this requires a high standard of record-keeping (21).

The analysis included documentation for ten patients over the age of 18 who were admitted to an intensive care unit at a university hospital in Norway for more than three days in the period 1 January 2018 to 31 May 2018. The sample size was considered to be sufficient to identify language use and patterns in practice (22).

Data material

The data material included the document type ‘SPL note/evaluation’ from the DIPS patient record system. The documents consisted of two parts. The top part, which was white, was the evaluation and assessment note and consisted of twelve categories - functional areas - where the nursing care provided is described in free text in a systematic order.

The bottom part, which was coloured, was the treatment plan. This is where the patient’s problems were expressed or classified according to NANDA in a yellow field at the top of the record. This field was followed by a red field, where the goal of the nursing care is stated as free text. The NIC, which described nursing interventions, appeared in the green field at the bottom of the record.

An RN on the ward assisted in the data collection. On a random day, the RN reviewed all hospitalised patients in the unit, six of whom met the inclusion criteria. The remaining four patients were selected by the RN from a list of previously admitted patients.

The evaluation and assessment notes included in the material for this study were printed individually and consisted of nine pages for each patient. The entire treatment plan was then printed as a single document, one for each patient.

The dataset totalled 110 pages. In order to anonymise the data, the patients were referred to as ‘Patient A’, ‘Patient B’ etc., and sensitive personal data was deleted.

Theoretical and methodological basis

Discourse can be understood as a specific way of talking about, describing and understanding a phenomenon (22). Discourse analysis provides a social constructivist approach to empirical data material, where the theoretical and methodological bases are merged.

This study applies the discourse theory of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe (23). Laclau and Mouffe (23) do not provide structural guidelines for the analysis, but have established discourse theoretical concepts that can be operationalised. In this study, we use the terms discourse, moment, nodal point, hegemony and antagonism (23, 24).

In Laclau and Mouffe’s (23) description of discourses, a picture is drawn of a whole, consisting of moments. A discourse is made up of moments. Moments are articulated signs within a discourse whose meaning has been temporarily determined.

The discourse has a core, known as a nodal point. A nodal point is a privileged sign around which the moments are organised and from which they derive their meaning. The hegemony concept is directly linked to a temporary locking of the discourse. Hegemony is a state in which a prevailing discourse is not challenged, but is perceived as expected and natural.

Antagonism describes a contrast between existing discourses and is synonymous with conflict. Antagonism occurs when different discourses mutually impede each other.

Analysis

In line with the discourse analysis, nursing records are analysed from a specific theoretical angle. In the analyses of the discourses, emphasis was placed on reproducing words and terms exactly as they were written. The first step in the analysis entailed examining the patterns in the language in relation to the type of text used, and its consistency and regularity (22).

Treatment plans and evaluation and assessment notes were examined separately. Moments were identified here to shed light on the nodal point and subsequent discourses. In line with the discourse theory, the results were compared in order to understand how the notes and treatment plans relate to each other (24).

In the review of the evaluation and assessment notes, we used Moen et al.’s (1) breakdown of RNs’ work into three different functions: the independent, the collaborative and the delegated.

This way of systematising the descriptive free text gave us a good understanding of the data material and enabled us to identify words and terms of meaning as they appear in the nursing records.

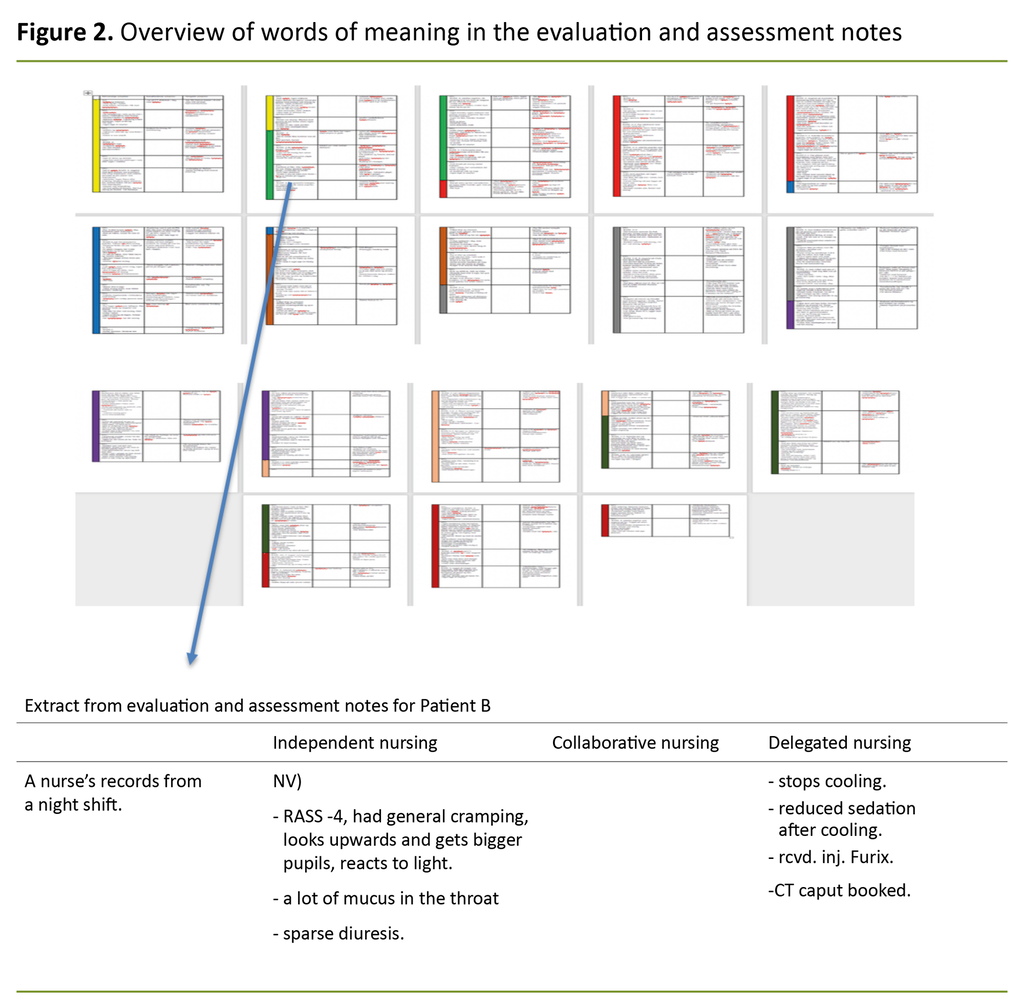

The documentation was coded with colours for each patient (Figure 2). The first author sorted the text in a Word document, and the co-authors participated in the analysis work and identification of the discourses.

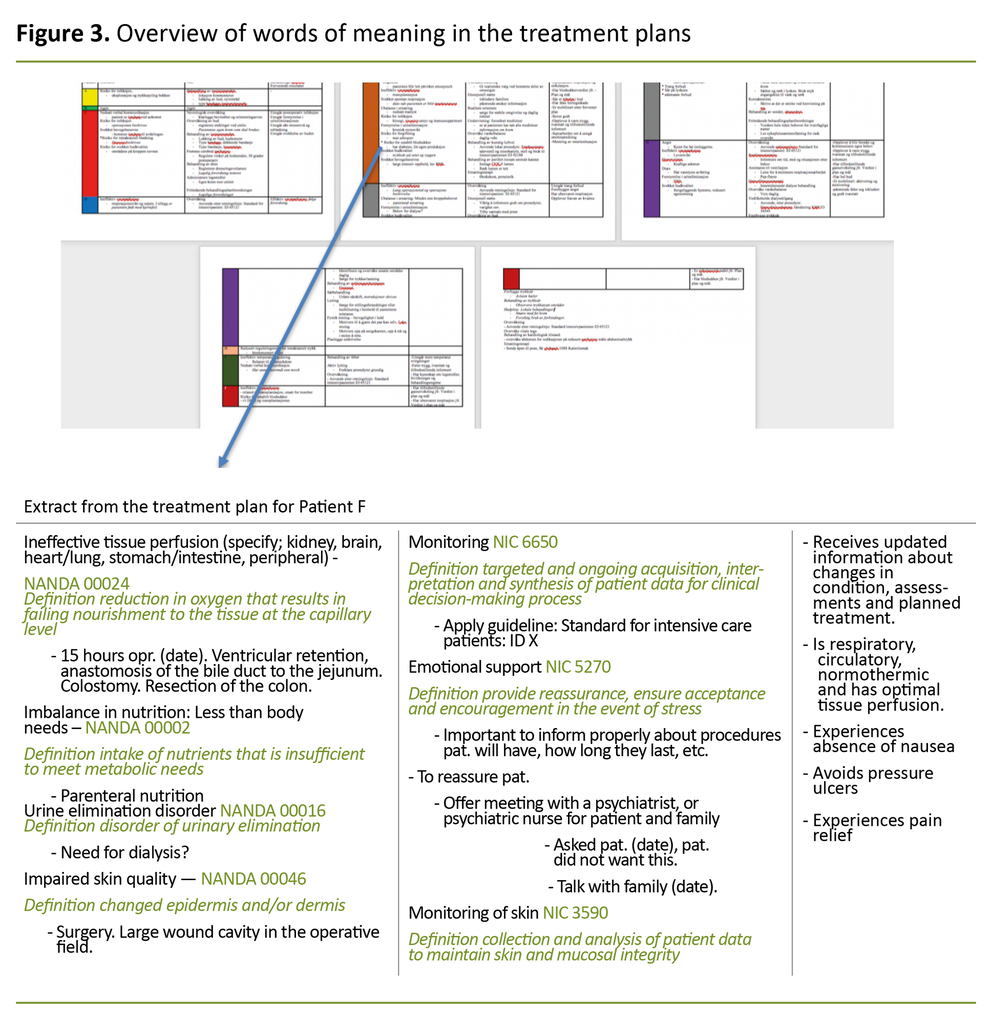

We reviewed the treatment plans using the same method (Figure 3). Here we found that the treatment plans not only contained the terms from the classification systems, but that the RNs supplemented the NANDA diagnoses and the NIC interventions with additional free text. We therefore chose to sort the text so that the code systems were separated from the supplementary free text. We split them into diagnoses, interventions and goals.

We chose to focus on the RNs’ documentation in two patient records: Patient B and Patient F. The reason for this was that they constituted two extremes in the dataset: Patient B did not have a treatment plan, while Patient F had one of the most extensive treatment plans. These two patient records were used and viewed in light of the other patients’ records.

Results

We analysed the text using Laclau and Mouffe’s (23, 24) terms. One of the main findings is that the evaluation and assessment notes contained different patterns and language use from the treatment plans. In line with the discourse theory, a discourse is identified by uncovering the delimitation of the texts, and in our texts, a clear delimitation emerged.

One of the main findings is that the evaluation and assessment notes contained different patterns and language use from the treatment plans.

The differences that emerged from the comparison of the evaluation and assessment notes and the treatment plans helped us to identify the two prominent discourses, which we refer to as the ‘care discourse’ and the ‘problem-focused discourse’.

Care discourse

The documentation in the evaluation and assessment notes is based on the patient’s basic needs and is aimed at the patient’s well-being, welfare and ability to cope in the relevant situation.

This reflected a care discourse. It consisted of descriptive free text and seemed to be shaped by words and terms relating to the context. ‘No contact’ or ‘the patient is on the surface’ says little to those who do not share the same reality of practice.

This reflected a care discourse.

This care discourse is identified through the nodal point relation. The combination of the various moments constitutes the care discourse, and these are: signs, cooperation, reaction (Figure 4).

Many patients in an intensive care unit suffer respiratory failure (21). The respiratory failure is not clearly shown in the evaluation and assessment notes, but is indicated on the basis of the patient’s status and how the situation develops.

The RN describes signs that indicate breathing problems. This applies to entries of ‘subdued lung sounds’, ‘sudden saturation drop’ and ‘rapid RR’ (respiratory rate). Interventions are then recorded, and if it says ‘perceptible mucus’, the RN attends to the patient. The notes then state ‘brought up a small amount of viscous mucus’.

The RNs give a homogeneous description of secretions, such as ‘bloody’, ‘runny’, ‘pink’, ‘viscous’, ‘little’ and ‘perceptible’ A basic feature seems to be that entries are reproduced in the nursing records in the same way for all patients. Likewise, they write that the patient ‘has had suction’ or ‘has been down in the tube’. For someone who is not familiar with the context, the meaning may be unclear.

The review of the notes shows that the descriptions relate to the patients having pulmonary secretions, and because they are intubated, it is not possible for them to cough it up. Thus, the suction procedure becomes a natural part of the care discourse and way of writing. The description ends with how the patient reacts to the interventions.

Problem-focussed discourse

A problem-focused discourse emerges in the treatment plan, where formalised language from the NANDA and NIC classification systems was used. We identified the moments as problem, goal and intervention.

In discourse theory, a plan is a nodal point, as it is a privileged sign around which the other signs are organised and from which they derive their meaning (Figure 5). It also shows how NANDA and NIC are used in combination with supplementary free text. We saw the same practice for the other patients as well.

The nodal point plan calls attention to a structuring of nursing, where a traffic light colouring system is used. Amber, which can be associated with failure, warning and illness, corresponds to the problem moment, where the patient’s problem is defined. The NANDA diagnosis urinary elimination disorder is cited and individualised with the description ‘need for dialysis’.

The next section is a red field that includes the goal moment. According to the classification system, the NANDA diagnosis can be related to multiple factors. Therefore, ‘is respiratory’, ‘circulatory, normothermic’ and ‘has optimal tissue perfusion’ are assumed to be relevant goals.

The green field refers to the last moment of the problem-focused discourse, intervention. It is common here to refer to procedures, standards or guidelines that point to one way of doing things. Three interventions, all taken from the NIC, are described.

The first is monitoring, which is detailed in the Norwegian guideline on care standards for intensive care patients. The guideline states the extent to which the patient should be monitored, and what interventions can be undertaken. It is also used for the other patients and can be linked to other NANDA diagnoses.

The next intervention is hemofiltration, which refers to a local procedure, and the last one is temperature control. Here it is emphasised that the patient’s temperature must be regulated using a WarmTouch blanket.

This discourse generally reflects how the nursing care provided is problem-oriented and based on a plan for treating illness. The terms from NANDA and NIC are used in combination with free text to individualise the treatment plan.

Discussion

The study shows that the two discourses provide different starting points for the nursing records and make different contributions. In the care discourse, the nursing records appear to be evidence-based, while the problem-focused discourse is aimed at a different type of structure and order.

Care discourse is most prominent

The care discourse is pervasive in the nursing records and generally seems to play an independent and hegemonic role in that it is used most frequently and appears to be the most important and most comprehensive.

The independent and hegemonic role is evidenced by the fact that the evaluation and assessment notes have a certain gravitas and continuity, in contrast to the treatment plans. The problem-focused discourse could be regarded as more random, and as such seems to play a smaller role.

The care discourse is pervasive in the nursing records.

The treatment plan is updated less frequently, and the evaluation and assessment notes contain important information that is not linked to the treatment plan. However, the presence of a hegemonic care discourse in the nursing records reduces the meaning of the notes to a level of detail that is understandable to those who are familiar with the context.

Since the meaning is obscured, the health care and its outcomes are not clearly communicated, something that Buus and Hamilton (20) also point out in their study.

Nursing records need to be more useful

The health policy guidelines require nursing records to be made more useful. Reference is often made to how the focus has therefore changed ‘from structure to process to outcome’ (25) over the last 30 years.

Using NANDA and NIC in nursing records will lead to a standardisation that may make the nursing records more explicit (26). Standardisation is rooted in health policy strategies and is considered to be a means of improving quality and efficiency in the health service (15).

It has also been shown that classification systems such as NANDA and NIC can facilitate the collection and utilisation of data for measuring and monitoring the health care provided by RNs (12, 27).

It is further pointed out that standardisation strengthens the connection between science and practice, partly because records designed according to these classification systems can be used to study the quality of health care and its effects on the patient’s outcome or goal achievement (13).

Although the quality of such record-keeping practices is constantly questioned (28), many studies point to the positive effects of using NANDA and NIC in nursing records (12). In this study, we examined the classification systems in light of discourse theory.

The findings show that the code system was largely supplemented with free text. The study also shows that, despite the use of the classification systems, it is not the problem-focused discourse in the treatment plan that guides practice, even though this has been the intention (29).

The documentation practice is difficult to change

The findings point more in the direction of the record-keeping reflecting a certain conflict or tension between the two discourses, where the assessment notes play a hegemonic role. Jefferies et al. (17) refer to how the RNs understand and use local words and terms among themselves.

The assessment notes play a hegemonic role.

The care discourse has traditionally given the nursing records content and meaning. In line with Laclau and Mouffe (23), it may seem that the care discourse represents a certain gravitas and stability, which in turn makes it difficult to change the documentation practice.

Molina-Mula et al. (18) characterise the situation as paradoxical. They explain that the patient’s individuality disappears due to the standardised language in the problem-focused discourse, thereby dehumanising the health care described in the treatment plans.

Only problems are entered in the records

The privileged sign nodal point in each discourse constitutes the difference in the record-keeping practice. What distinguishes the discourses from each other is that in the problem-focused discourse, the nodal point problem is the core component.

As appears to be the case in the data material, this means that if there is no problem, nothing will be recorded. The treatment plans may lead to only patient data relating to clinical complications and physiological conditions being recorded. This neglects documentation that can ensure continuity and record emotional issues and time-consuming decision-making processes (18).

Rather than giving the treatment plans a strong governing role in nursing records, as provided for in health policy guidelines, a greater degree of situational and independent judgment can be applied, as is the case in the care discourse.

This study points to precisely this relationship by showing that the care discourse has an important role and function that should be protected. Laclau and Mouffe’s (23) discourse theory paves the way for a discussion about which discourses exist in nursing records, and how they are or should be interrelated.

Conclusion

The two discourses that have been outlined; the care discourse and the problem-focused discourse, show two different starting points for what is recorded. The care discourse is organised according to a comprehensive review of the patient. In contrast, the problem-focused discourse is aimed at goals and interventions that are filled with procedures, standards and guidelines.

One of the main findings is that the evaluation and assessment notes written in free text are used to the greatest extent. The treatment plans are not updated and are used more sporadically. The care discourse largely seems to play an independent and hegemonic role in the nursing records.

The data material does not provide a basis for concluding that the care discourse in general is or should be predominant in RNs’ record-keeping. Despite the small dataset in the study, the discourse analysis can be used as a springboard for reflection on language use and patterns in nursing records, which gives it a transfer value.

The study can provide a basis for systematic and dialogical development of the quality of nursing documentation and can support systematic reflection on the record-keeping practices of RNs and their colleagues – in relation both to treatment plans and evaluation notes.

The study indicates a continuous need for more knowledge about how nursing care is actually recorded in patient records.

References

1. Moen A, Quivey M, Mølstad K, Berge A, Hellesø R. Sykepleieres journalføring: dokumentasjon og informasjonshåndtering. Oslo: Akribe; 2008.

2. Direktoratet for e-helse. Terminologi for sykepleiepraksis – konseptutredning. Oslo: Direktoratet for e-helse; 2018.

3. Meld. St. 11 (2015–2016). Nasjonal helse- og sykehusplan (2016–2019). Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2015.

4. Direktoratet for e-helse. Nasjonal handlingsplan for e-helse 2017–2021. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2017. IE-1015.

5. Vabo G. Dokumentasjon i sykepleiepraksis. 3rd ed. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2018.

6. Norsk redaksjonsutvalg for klassifikasjonssystemene NANDA NICoNOC. NANDA sykepleiediagnoser: definisjoner & klassifikasjon, 2001–2002. Norwegian ed. Oslo: Akribe; 2003.

7. Mølstad P, Bulechek GM, Dochterman JM. Klassifikasjon av sykepleieintervensjoner (NIC). 4th ed. Oslo: Akribe; 2006.

8. von Krogh G, Dale C, Naden D. A framework for integrating NANDA, NIC, and NOC terminology in electronic patient records. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005;37(3):275–81.

9. Strudwick G, Hardiker NR. Understanding the use of standardized nursing terminology and classification systems in published research: a case study using the International Classification for Nursing Practice. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2016;94:215–21.

10. Pyykko AK, Laurila J, Ala-Kokko TI, Hentinen M, Janhonen SA. Intensive care nursing scoring system. Part 1: Classification of nursing diagnoses. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. 2000;16(6):345–56.

11. Muller-Staub M, Lavin MA, Needham I, Van Achterberg T. Meeting the criteria of a nursing diagnosis classification: Evaluation of ICNP, ICF, NANDA and ZEFP. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44(5):702–13.

12. Paans W, Muller-Staub M. Patients' care needs: documentation analysis in general hospitals. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge. 2015;26(4):178–86.

13. Dochterman J, Titler M, Wang J, Reed D, Pettit D, Mathew-Wilson M, et al. Describing use of nursing interventions for three groups of patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005;37(1):57–66.

14. Duarte RT, Linch GF, Caregnato RC. The immediate post-operative period following lung transplantation: mapping of nursing interventions. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2014;22(5):778–84.

15. Meum T, Ellingsen G, Monteiro E, Wangensteen G, Igesund H. The interplay between global standards and local practice in nursing. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2013;82(12):e364–74.

16. Kautz DD, Kuiper R, Pesut DJ, Williams RL. Using NANDA, NIC, and NOC (NNN) language for clinical reasoning with the Outcome-Present State-Test (OPT) model. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications. 2006;17(3):129–38.

17. Jefferies D, Johnson M, Nicholls D. Nursing documentation: how meaning is obscured by fragmentary language. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59(6):e6–e12.

18. Molina-Mula J, Peter E, Gallo-Estrada J, Perello-Campaner C. Instrumentalisation of the health system: an examination of the impact on nursing practice and patient autonomy. Nursing Inquiry. 2018;25(1).

19. Hyde A, Treacy MP, Scott PA, Butler M, Drennan J, Irving K, et al. Modes of rationality in nursing documentation: biology, biography and the ‘voice of nursing’. Nursing inquiry. 2005;12(2):66–77.

20. Buus N, Hamilton BE. Social science and linguistic text analysis of nurses' records: a systematic review and critique. Nursing Inquiry. 2016;23(1):64–77.

21. Søreidem E, Flatland S, Flaatten H, Helset E, Haavind A, Klepstad Pl, et al. Retningslinjer for intensivvirksomhet i Norge. Oslo: Norsk Anestesiologisk Forening, Norsk sykepleierforbunds landsgruppe av intensivsykepleiere; 2014. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/2265711/Retningslinjer_for_IntensivvirksomhetNORGE_23.10.2014.pdf (downloaded 01.10.2020).

22. Jensen LB. Indføring i tekstanalyse. 2nd ed. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur; 2011.

23. Laclau E, Mouffe C. Hegemony and socialist strategy towards a radical democratic politics. 3rd ed. London: Verso; 2014.

24. Jørgensen MW, Phillips L. Diskursanalyse som teori og metode. Frederiksberg: Roskilde Universitetsforlag, Samfundslitteratur; 1999.

25. Thoroddsen A, Ehnfors M. Putting policy into practice: pre- and posttests of implementing standardized languages for nursing documentation. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16(10):1826–38.

26. Lunney M, Delaney C, Duffy M, Moorhead S, Welton J. Advocating for standardized nursing languages in electronic health records. J Nurs Adm. 2005;35(1):1–3.

27. Rabelo-Silva ER, Cavalcanti ACD, Caldas MCRG, Lucena AF, Almeida MA, Linch GF, et al. Advanced Nursing Process quality: Comparing the International Classification for Nursing Practice (ICNP) with the NANDA-International (NANDA-I) and Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC). Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2017;26(3-4):379–87.

28. De Groot K, Triemstra M, Paans W, Francke AL, De Groot K. Quality criteria, instruments and requirements for nursing documentation: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2019;7:1379–93.

29. Holen-Rabbersvik E, Nyhus VA, Hagen O, Graver C, Vabo G, Svanes M. Veileder for klinisk dokumentasjon av sykepleie i EPJ. Oslo: NSFs faggruppe for e-helse; 2017. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/3258400/cache=20171602103055/Veileder_v5.1..pdf (downloaded 25.03.2019).

Comments