Family members’ experiences of end-of-life care during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic

The patient received good nursing care and symptom relief. However, the lack of communication, strict visiting restrictions and the use of personal protective equipment constituted a burden for both patients and family members.

Background: The COVID-19-pandemic impacted on the care of seriously ill patients both with and without COVID-19. We anticipated that the pandemic and lockdown of Norway would also affect the holistic care of the dying and their family members.

Objective: To gain insight into how family members experienced both end-of-life care for a close relative and support for themselves during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway.

Method: Family members who had lost a close relative completed an open, online questionnaire that was available from July to October 2020. The form was answered anonymously by 102 bereaved persons. The questionnaire was based on CODE (Care of the Dying Evaluation), with additional questions linked to the pandemic and an option to add free-text comments. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, and free-text comments were analysed thematically in five steps.

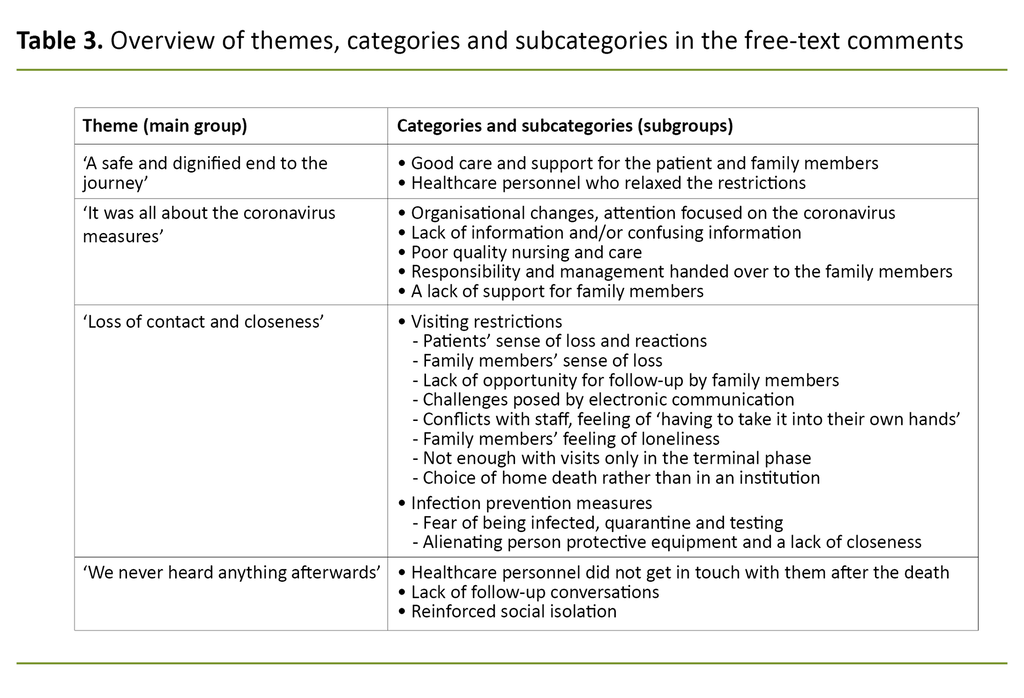

Results: A total of 83 per cent of the family members were women, median age group 50–59 years, and 61 per cent had lost a parent. Of the deceased, 46 per cent were women, 75 per cent were >70 years, 48 per cent had cancer and 24 per cent had dementia. A total of 83 per cent died between March and June. Sixteen per cent died at home while 33 per cent died in hospital and 40 per cent died in a nursing home. Most of the family members (85 per cent) were of the opinion that the patient had received satisfactory treatment and nursing care while 35 per cent felt that they themselves had not received adequate support during the patient’s final days. Four themes stood out in the free-text comments: ‘A safe and dignified end to the journey’ describes the good care and individualised approach that many experienced despite the pandemic and lockdown. ‘It was all about coronavirus measures’ includes experiences of poor availability and quality of treatment and nursing care, inadequate follow-up of family members and a lack of information or confusing information. ‘Loss of contact and closeness’ deals with the experiences and consequences of visiting bans, visiting restrictions and infection control measures. ‘We never heard anything afterwards’ describes the lack of contact after the death.

Conclusion: Family members largely considered the nursing care and symptom relief to be good. However, the lack of communication, strict visiting restrictions and alienating personal protective equipment led to feelings of uncertainty and a sense of loss and frustration during both the patient’s final days and afterwards.

Introduction

End-of-life care is a key task for the health and care services in the community nursing service, nursing homes and hospitals. This encompasses both the patient and family members. In recent years, this area has been reinforced by national guidance for end-of-life care (1) and a national guide for family members that contains a separate chapter on support for family members during the end-of-life phase (2).

Family members play a key role in providing support and care for sick patients, but this role also entails burdens. Research shows that providing support to family members plays a vital role in reducing stress during the period of illness and in counteracting complex grief reactions such as prolonged sorrow and impaired social functioning (3).

Measures taken during the COVID-pandemic to limit infection immediately led to major upheavals in most areas of society, including the care of seriously ill patients (4). Isolation, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and a ban or restrictions on visits reduced contact between patients and family members, and between family members and healthcare personnel. Healthcare personnel had to make difficult prioritisations. Questions were soon being asked about whether public health measures were compatible with individualised end-of-life care (5).

Over time, a number of publications on experiences with caring for the dying during the pandemic (6–9) have appeared. In Norway, 13 255 people died in the period from March to June 2020 (10), of whom 256 died from COVID-19 (11). Thus the lockdown of the country during this period affected thousands of family members of patients in the terminal phase.

When the COVID-19-pandemic struck in March 2020, the Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, Western Norway was in the process of starting up a new EU-funded project on end-of-life care (12). As a result of the pandemic, it was impossible to recruit patients and family members in hospitals and nursing homes for this project. Meanwhile, the pandemic and lockdown of Norway made the research theme more relevant than ever. In conjunction with our international partners, we therefore decided to invite family members and healthcare personnel who had experienced deaths during the pandemic to share their experiences and perceptions by answering a questionnaire. We present the results of the questionnaire from the family members in this article.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain insight into how family members who had lost a close relative during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic experienced the care given to their dying relative and themselves.

Method

Recruitment and data collection

We invited family members to answer an anonymous, online questionnaire on the website of the Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, Western Norway. Contact persons in the regional and national palliative care communities shared the invitation on social media and other websites. The survey was mentioned on some news channels, and we advertised in a couple of newspapers in Western and Eastern Norway.

No bereaved family members were contacted about the survey directly, but healthcare personnel could mention it if they were in contact with them for other reasons. The only criterion for participation was having experienced the death of a close relative over the age of 18 after 1 March 2020. The survey was available from 29 June until 30 October 2020.

The questionnaire was based on the international version of the Care of the Dying Evaluation (CODE) (13). CODE is a validated questionnaire on the care of the dying and support for family members during the patient’s final days. It has been translated, and has been used in Norway previously in connection with an international research project (14, 15).

The questionnaire covers treatment and nursing provided by nurses and doctors, pain relief and other symptoms, communication with the treatment team, emotional and spiritual support and the circumstances of the death. In addition, the questionnaire includes demographic questions about the patient and the respondent, i.e. the family member.

In the present study, the research group also added questions linked to the COVID-19 pandemic and the grieving process of family members. Finally, the participants were invited to answer a follow-up questionnaire or to participate in an interview. The results of the follow-up surveys are not presented here.

The participants had the option of giving further comments on the following questions: ‘Do you think that the treatment or nursing care given to your relative was limited because of the coronavirus crisis?’ and ‘Where did he/she die?’. In addition, participants had the option of giving free-text comments at the end of the questionnaire: ‘We welcome further comments on any of the topics/questions in the questionnaire: What went well, what was not so good, and what could have been improved?’

Analysis

We analysed the responses to the questions with fixed response options in the online questionnaire by means of descriptive statistics, using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. The free-text comments were analysed using thematic analysis (16).

We had not decided on the themes and categories beforehand but identified them on the basis of the text material. Two of the authors – DFH and ER, a doctor and RN respectively with experience of qualitative methods – first read over all the comments several times to form a general impression of the material. Then they manually coded the meaning units separately. The two authors discussed differences in the coding until agreement was reached. These codes were then manually placed in thematic units forming categories and subcategories.

Afterwards we condensed text content in each category and subcategory using illustrative quotations. The material was again reviewed in light of these categories. After discussing the results in the authors’ group, we collated them at the end under a few, overarching themes. The method and results are presented in accordance with the COREQ checklist (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) (17).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South-eastern Norway (reference number 35035 REK South-eastern D) and was submitted to the data protection officer at Bergen Hospital Trust.

Results

Participants and patients

A total of 179 people opened the questionnaire; 102 completed it and could be included in the study. The participants were family members of patients. Table 1 describes the family members and the patients they talked about. The majority of family members were women in their fifties and sixties. The patients were older: 75 per cent were over 70 years of age. Approximately half of them had cancer and a quarter had dementia. The distribution of place of death varied between home, hospital and nursing home.

Assessment of treatment, nursing and care

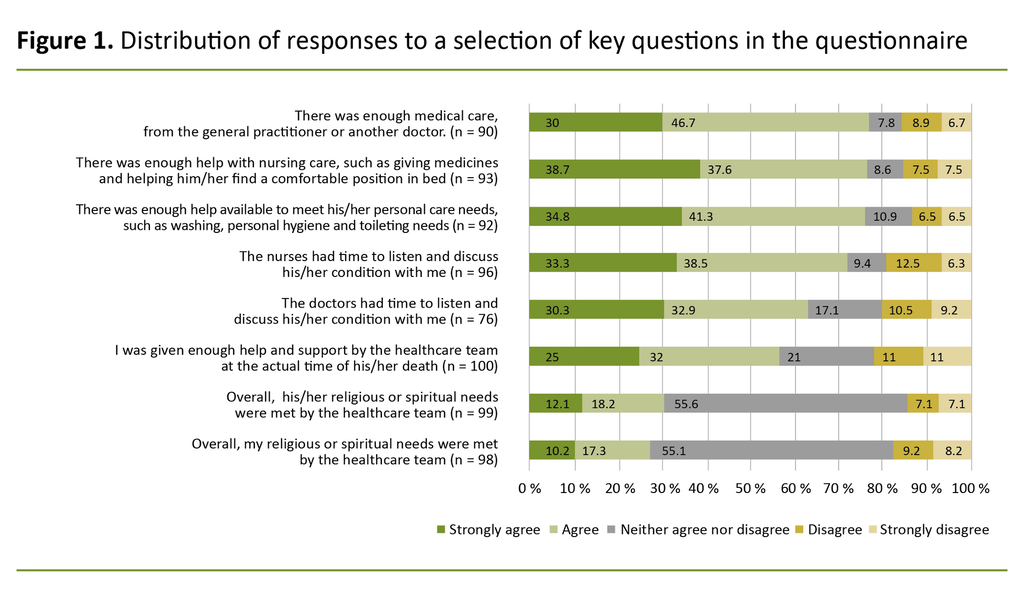

Figure 1 shows the responses to key questions in the questionnaire’s different thematic areas. More than 75 per cent of the participants thought that the patient received adequate medical treatment and nursing care. In addition, approximately 10 per cent neither agreed nor disagreed with this. The distribution of those who disagreed, approximately 15 per cent of the family members, varied between home, hospital and nursing home.

Nineteen per cent of the participants believed that the treatment and nursing care given to their dying relative was ‘undoubtedly’ limited because of the coronavirus crisis, and 16 per cent thought that it was ‘probably’ limited because of this (N = 102).

The responses showed that the patients had typical symptoms in the terminal phase, such as dyspnoea, pain, agitation and restlessness. Ninety per cent or more of the participants said the healthcare personnel had done enough to help relieve the symptoms either ‘the whole time’ or ‘some of the time’.

A total of 81 per cent of the participants were informed about their relative’s imminent death, but only 49 of the 100 respondents were informed about what to expect at the terminal phase, for example the symptoms that might arise. Of the 51 who did not receive such information, 28 (55 per cent) believed that it would have been helpful.

However, while the majority of the participants considered the treatment and nursing care given to the patient to be good, 24 per cent rated the emotional support they themselves received from the care team as poor (21 per cent said ‘excellent’, 34 per cent ‘good’, 21 per cent ‘fairly good’, n = 100).

In answer to the question, ‘Overall, in your opinion, did you receive satisfactory support during his/her final two days?’, 65 per cent answered ‘yes’ and 35 per cent ‘no’ (n = 101).

Free-text comments

A total of 74 of 102 questionnaires contained free-text comments. Ten of the comments had purely factual content, 19 presented positive experiences, 57 negative experiences and 29 a mixture of positive and negative experiences. While the questionnaire itself focused on the patient’s final two days, the free-text comments covered a longer period.

Most of the comments were detailed – the text material amounted to almost 16 000 words. The extensive body of material meant that there was little need for interpretation so that the formulations in the condensed meaning units presented below are close to the original text. Table 2 shows a couple of examples of the analysis process. Based on the text analysis, care experiences could be divided into four themes, as presented in Table 3.

A safe and dignified end to the journey

Positive comments related to the healthcare personnel who did their utmost to ensure that the patient’s final days were good and meaningful to them and their family members. Some participants said that the treatment and nursing care were given without restrictions, while others said that dying patients were prioritised despite the limitations of the coronavirus crisis.

Several expressed their profound gratitude to the community nursing service and the GP, who maintained good routines, as well as to the staff of the nursing home and hospital, who provided effective symptom relief and made it possible for the family to be with their dying relative. Their gratitude was also extended to employees who showed compassion, relaxed the restrictions and bent the visiting rules so that family members could say goodbye:

‘My sister and I were allowed to be with our father around the clock in the four days prior to his death. Both our father and we were PARTICULARLY well looked after. We have no complaints either about his nursing care or the consideration shown to us. This applies to everyone from the trainee in the ward, the chaplain and the doctor in the intensive care unit. In retrospect, it feels good to be spared the thought that someone could have done something differently.’ (Participant no. 20, hospital)

It was all about coronavirus measures

Others had a very different experience. The GP and community nursing service staff were afraid of being infected, and either did not turn up or only paid short visits where they kept a safe distance to the patient and family members. The option of spending time in a palliative care unit was dropped, infection control measures prevented patients from being able to switch between spending time at home and in the nursing home, and patients were discharged from hospital to free up beds for COVID-19 patients.

In nursing homes, some staff had to go into quarantine and some were transferred. There were also more substitute nurses and untrained personnel, and staff with no experience of dying patients had to take over responsibility for them:

‘When she was isolated in a room after being infected with COVID-19, all dignified nursing disappeared …. I washed her myself after she had died, and saw how poor the nursing care had been. She had big bedsores.’ (Participant no. 162, nursing home)

Staff had to spend a lot of time attending information and training meetings. Moreover, the participants found that the nurses kept their distance and only spent short periods of time in the patients’ rooms. The offer of physiotherapy or visits from a chaplain was discontinued. Family members described how they more or less had to take over the care of their dying relative themselves:

‘We were more or less left to our own devices for several days when it came to caring for our dying relative.’ (Participant no. 155, nursing home)

Many family members experienced a lack of contact and information from the hospital or nursing home after Norway went into lockdown on 12 March 2020. They felt that the follow-up they received as family members had been highly inadequate:

‘My father was provided with respite care on a Friday and by Sunday night, he was dead. During that period, there was NO contact between the institution and me as a relative.’ (Participant no. 147, nursing home)

‘We had no contact with the hospital during the last week. We didn’t know it was so serious. Got a phone call in the morning saying we could visit. It was a long way to drive, and he died 10 minutes before I got there.’ (Participant no. 41, hospital)

Family members found it hard to receive information about their dying relative in a brief telephone conversation or just a text message. They also found the information confusing or unclear, especially when it came to visiting restrictions and infection control measures:

‘The infection control rules changed every day. In the final days, PPE was no longer needed. Being the relative of a patient at the hospital felt chaotic, confusing and unsafe.’ (Participant no. 99, hospital)

Loss of contact and closeness

Visiting restrictions were the main theme in most comments. Some families opted for a home death. Normally, they would not have considered this, but their experiences of a hospital in lockdown meant that they chose this option despite the uncertainty. Most of the people who had dealings with hospitals and nursing homes experienced days or weeks without any possibility of visiting, followed by strict limitations in both the number of visitors and the frequency and duration of the visit.

Electronic communication did not work as an alternative for many of the patients because they did not manage to master the technique. Nor was telephone contact possible for the weakest patients. Visiting restrictions had profound consequences for the patients:

‘My father received a permanent place at the nursing home just as the country was going into lockdown. It was a terrible time for him as he didn’t understand what was going on and felt completely let down. He first saw us again at the beginning of May – at a distance of 2 metres, without any opportunity to hug his loved ones.’ (Participant no. 21, nursing home)

‘He died of grief and a sense of abandonment as a result of the ban on visits and the fact that the staff were very uncertain about how to interpret visiting rules; I saw him twice for 15 minutes in the course of the week before he died at the weekend.’ (Participant no. 146, nursing home)

The visiting ban also seriously impacted on the family members. In addition to the sense of loss of contact and a lack of opportunity to show care and consideration, they felt despair and uncertainty about their inability to provide proxy information about the patient or observations on the development of the illness:

‘The visiting restrictions meant that we were unable to keep up with the development of the illness and her general condition. She certainly became weaker and weaker, but for us the end came abruptly. The nursing staff probably wouldn’t see the decline in the same way as those of us who knew her would have done.’ (Participant no. 93, municipal institution)

Conflicts arose because the staff were uncertain how to apply the visiting rules. The participants found it stressful to have to ‘take it into their own hands’ to gain admittance when patients deteriorated. The limitations on the number of visitors also created a feeling of loneliness for those who had to deal with the situation on their own. The grieving process was impacted by the fact that family members could not all be together with their dying relative at the same time:

‘It was really hard being the only family member allowed to be with your dying relative. No one other than me was allowed to be there for the last four days.’ (Participant no. 24, nursing home)

Most participants, but not all, were allowed to be with their dying relative in their final days. However, this could not compensate for the lack of visits in the preceding weeks. On the contrary, they felt a great sense of loss when they were unable to talk about things while the patient was still capable of participating in a conversation:

‘Mum was hospitalised a few days before the lockdown on March 12. We had no idea that we wouldn’t see her again until we came to visit her two days before she died. It’s really painful to think that we couldn’t be with her at the end of her life, when we could still communicate with her.’ (Participant no. 59, local authority institution)

The participants described their fear of being infected and the stress of testing and quarantine. Even though they understood that PPE was necessary, they found it alienating – it created distance and insecurity:

‘It was traumatic to meet him wearing full PPE, and that clearly affected him.’ (Participant no. 99, hospital)

The participants also thought that the rules had been over-strictly applied in some cases:

‘It seemed unnecessarily brutal that my grandfather was not able to hug his wife when she visited after several weeks apart.’ (Participant no. 13, nursing home)

We never heard anything afterwards

In this category we find clear disappointment that healthcare personnel did not get in touch after the death. These experiences were independent of the place of death and the length of the contact or stay. Promises of follow-up conversations were not kept. There was a particularly strong need to be allowed to process impressions together with healthcare personnel because other social contact was so limited:

‘In retrospect, we find it strange that neither the GP nor the community nursing service got in touch with us in the days following the death. Dad was the patient. The patient was dead. Case closed.’ (Participant no. 118, home)

Discussion

The results show that the majority of participants felt that the dying person was well looked after, but healthcare personnel’s communication with family members and the support they received was less satisfactory. Visiting restrictions and other coronavirus measures had a great impact on both patients and family members.

Several publications have appeared about end-of-life care during the pandemic in Norway but these have focused on patients with COVID-19 (18, 19).

Patients received poorer services in the final phase of life

Our material deals mainly with the death of patients who died neither of nor with COVID-19. Our findings confirm the suspicion of Berit Hofset Larsen et al. that ‘some patients may have received poorer service in the final phase of life as a result of a lack of competence in palliative care, and the absence of close family members’ and that ‘many family members have suffered due to their inability to be with their elderly, sick and dying relatives’ (20).

The responses in our survey indicate that competence in symptom relief at the end of life was generally satisfactory and that the dying patients received good care. Nevertheless, the free-text comments showed that some patients suffered as a result of a lack of competence because of changes in the service provision or healthcare personnel as a result of the pandemic.

There was a clear deterioration in the holistic, interdisciplinary care that characterises palliative care, for example the discontinuation of the services of chaplains and physiotherapists. However, the absence of close family members was one of the main reasons for the patients receiving poorer service at the terminal phase.

Family members missed having contact with patients and healthcare personnel

The participants described how they missed being together with the patients and having communication with the personnel. These findings concur with recent international literature on the situation of family members and the bereaved during the pandemic. A similar German study highlighted a high degree of stress among the bereaved, and that they felt a lack of proactive communication and empathy on the part of the staff (8).

A Dutch interview study showed that the feeling of isolation and insufficient opportunity to say goodbye combined with a lack of attention and communication on the part of the personnel compromised the patients’ and family members’ sense of dignity (9).

The results of a similar UK study showed that family members had greatly increased needs for communication when they themselves could not be with their loved ones, and healthcare personnel played a key role as a link between the patient and their family members (6).

Palliative care is often referred to as patient centred as opposed to disease centred (21), but palliative care involves focusing attention on both the patient and their family members (22). Although family-centred care is a philosophy of care best known in paediatric health care (23), it is also consistent with the palliative approach (24).

Based on this philosophy, healthcare personnel see the family and the patient as a unit and as partners. Family members are important decision makers together with the patient and staff, and collaborate with staff in the follow-up of patients.

This approach requires considerable contact between the patient and their family members as well as joint conversations with the staff. As many participants in our study were not allowed to be present with the patient, family-centred care became impossible in practice. Many participants mentioned ‘being cut off’ as a source of loss and frustration.

A recently published American study found that bereaved family members who had experienced good electronic communication with the hospital during the pandemic and had been involved in decisions about treatment and care, assessed end-of-life care as significantly better (7).

Our study shows that this type of communication was introduced to a very limited extent and/or received low priority during the first phase of the pandemic in Norway. The results also showed that patients with dementia or in the terminal phase were often unable to use electronic communication methods. This means that healthcare personnel must actively facilitate contact, and this puts demands on personnel’s time and availability.

Even though the Norwegian Directorate of Health stated that good palliative treatment and care should be prioritised (25), it was difficult to balance the need for contact and infection control at the start of the pandemic (26). When guidelines for visits to health and care institutions were issued in May 2020, decisions were still largely based on discretion (27), and this was confirmed by our study.

Family members wanted more contact with their dying relative before the terminal phase

The study also showed that even though it is important to spend time with the dying person, family members are deprived of valuable time and opportunities if visits are limited only to the terminal phase. This finding was also emphasised in the German study (8), in which family members complained that the visiting ban had been lifted too late for them to say their goodbyes to their dying relative. The authors of the German study stressed that visits to patients showing a clear deterioration should be permitted, and should not only be limited to the terminal phase, including during a pandemic or in similar circumstances.

When comparing our results with a study of family members’ experiences of cancer-related deaths in Norwegian hospitals prior to the pandemic (15), our study now showed a far lower percentage of family members who were of the opinion that they had received adequate support in the patient’s final days (65 per cent versus 93 per cent).

The two studies both demonstrated poorer results for spiritual and existential care than for other aspects of care (Figure 1), and a sense of a lack of contact with healthcare personnel after the death. Therefore, these two aspects of support at the terminal stage do not seem to be specifically linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, but may have been reinforced by the isolation and increased feeling of loneliness many experienced in this period (28).

The findings in our study underline the importance of including family members in communication and decisions by adopting a family-centred approach. When visits are not possible, provision must be made for effective electronic communication.

Nevertheless, the main message is the importance of contact between the patient and their family members, and that staff should make every effort to facilitate visits throughout the entire course of illness. The family-centred approach must also include follow-up of bereaved family members.

The study’s limitations and strengths

The main limitation of the study is that it presents a relatively small, self-selected convenience sample. As the survey was anonymous, we cannot rule out the possibility that some family members completed the questionnaire more than once. However, we chose this approach because infection control restrictions prevented systematic recruitment of research participants.

The participants came almost exclusively from Eastern and Western Norway, where the study was most known. Nevertheless, as there was a national lockdown, we believe that these experiences are representative of Norway as a whole.

Free-text comments are often written by participants who have particularly positive or negative experiences (29). We regard this as a strength of our study in that it highlights the range of experiences. Even though the number of participants was low in relation to the number of deaths in the period, the participants represented all relevant care settings at the end-of-life phase.

Conclusion

In this study of the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, most family members found that their dying relative received satisfactory nursing care and symptom relief, regardless of diagnosis and place of death. In contrast, one in three family members found that they themselves did not receive satisfactory support during the patient’s final days.

The weak areas were communication and addressing emotional and spiritual needs. The visiting restrictions were very stressful for many, and visiting the patient during their final days could not compensate for being unable to visit them in the preceding weeks.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Helsedirektoratet. Lindrende behandling i livets sluttfase. Nasjonale faglige råd. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2018. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/faglige-rad/lindrende-behandling-i-livets-sluttfase (downloaded 12.04.2022).

2. Helsedirektoratet. Pårørendeveileder. Nasjonal veileder [Internet]. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 10.01.2017 [updated 28.01.2019, cited 12.04.2022]. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/veiledere/parorendeveileder

3. Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, Leurent B, King M. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 June;15(6):CD007617. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007617.pub2

4. NOU 2021:6. Myndighetenes håndtering av koronapandemien. Rapport fra Koronakommisjonen. Oslo: Departementenes sikkerhets- og serviceorganisasjon, Teknisk redaksjon. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2021-6/id2844388/ (downloaded 12.04.2022).

5. Yardley S, Rolph M. Death and dying during the pandemic. BMJ. 2020 April;369:m1472. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1472

6. Hanna JR, Rapa E, Dalton LJ, Hughes R, McGlinchey T, Bennett KM, et al. A qualitative study of bereaved relatives' end of life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med. 2021 May;35(5):843–51. DOI: 10.1177/02692163211004210

7. Ersek M, Smith D, Griffin H, Carpenter JG, Feder SL, Shreve ST, et al. End-of-life care in the time of COVID-19: communication matters more than ever. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021 August;62(2):213–22.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.024

8. Schloesser K, Simon ST, Pauli B, Voltz R, Jung N, Leisse C, et al. «Saying goodbye all alone with no close support was difficult» – Dying during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey among bereaved relatives about end-of-life care for patients with or without SARS-CoV2 infection. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 September;21(1):998. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-021-06987-z

9. Becqué YN, van der Geugten W, van der Heide A, Korfage IJ, Pasman HRW, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Dignity reflections based on experiences of end-of-life care during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry among bereaved relatives in the Netherlands (the CO-LIVE study). Scand J Caring Sci. 2021 October 9;10.1111/scs.13038. DOI: 10.1111/scs.13038

10. Statistisk sentralbyrå. Statistikkbanken. Døde. Tabell 12982: Døde i fylker per måned, etter kjønn og 5-årige aldersgrupper. Oslo/Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå; n.d. Available at: https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/12982/ (downloaded 12.04.2022).

11. Folkehelseinstituttet. Covid-19 assosierte dødsfall meldt til Folkehelseinstituttet etter uke for dødsfall. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 2020. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/sv/smittsomme-sykdommer/corona/dags--og-ukerapporter/dags--og-ukerapporter-om-koronavirus/#table-pagination-40512255 (downloaded 12.04.2022).

12. iLIVE: Living well, dying well. A research programme to support living until the end. Europakommisjonen; 2019. Available at: https://iliveproject.eu (downloaded 12.04.2022).

13. Mayland CR, Lees C, Germain A, Jack BA, Cox TF, Mason SR, et al. Caring for those who die at home: the use and validation of ‘Care of the Dying Evaluation’ (CODE) with bereaved relatives. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014 June:4(2):167–74. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000596

14. Mayland CR, Gerlach C, Sigurdardottir K, Hansen MIT, Leppert W, Stachowiak A, et al. Assessing quality of care for the dying from the bereaved relatives' perspective: Using pre-testing survey methods across seven countries to develop an international outcome measure. Palliat Med. 2019 March:33(3):357–68. DOI: 10.1177/0269216318818299

15. Haugen DF, Hufthammer KO, Gerlach C, Sigurdardottir K, Hansen MIT, Ting G, et al. Good quality care for cancer patients dying in hospitals, but information needs unmet: bereaved relatives’ survey within seven countries. Oncologist. 2021 July;26(7):e1273–84. DOI: 10.1002/onco.13837

16. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

17. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 December;19(6):349–57. DOI: org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

18. Brenne A-T, Nordbø A, Steine S, Fasting A, Berglund MA, Røynstrand E, et al. Palliativ behandling av pasienter med covid-19. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2020 April;140(8). DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0276.

19. Eriksen S, Grov EK, Lichtwarck B, Holmefoss I, Bøhn K, Myrstad C, et al. Behandling, omsorg og pleie for døende sykehjemspasienter med covid-19. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2020 April;140(8). DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0306

20. Larsen BH, Magelssen M, Dunlop O, Pedersen R, Førde R. Etiske dilemmaer i sykehusene under covid-19-pandemien. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2020 December;140(18). DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0851

21. Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, Albreht T, Anderson R, Bruera E, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018 November;19(11):e588–653. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

22. World's Health Organization (WHO). Palliative care. Key facts [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 05.08.2020 [cited 12.04.2022]. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

23. Kuo DZ, Houtrow AJ, Arango P, Kuhlthau KA, Simmons JM, Neff JM. Family-centered care: current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Matern Child Health J. 2012 February;16(2):297–305. DOI: 10.1007/s10995-011-0751-7

24. Kissane DW. Under-resourced and under-developed family-centred care within palliative medicine. Palliat Med. 2017 March;31(3):195–6. DOI: 10.1177/0269216317692908

25. Helsedirektoratet. Prioriteringsnotat 25. mars 2020: Prioritering av helsehjelp i Norge under covid-19-pandemien. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2020. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/beredskap-og-krisehandtering/koronavirus/prioriteringsnotat-prioritering-av-helsehjelp-i-norge-under-covid-19-pandemien (downloaded 12.04.2022).

26. Neerland BE. De sårbares pandemi. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2020 August;140(11). DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0583

27. Helsedirektoratet. Helsedirektoratets svar på oppdrag fra Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet om besøksstans og sosial isolering under covid-19 pandemien. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2020. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/beredskap-og-krisehandtering/koronavirus/anbefalinger-og-beslutninger/Helsedirektoratets%20svar%20p%C3%A5%20oppdrag%20fra%20Helse-%20og%20omsorgsdepartementet%20om%20bes%C3%B8ksstans%20og%20sosial%20isolering%20under%20covid%2019-pandemien.pdf/_/attachment/inline/7df4c198-78ae-4435-83c4-3a937ff2a768:ddb90898297230436ea4dbb93bcc648206a9f0e5/Helsedirektoratets%20svar%20p%C3%A5%20oppdrag%20fra%20Helse-%20og%20omsorgsdepartementet%20om%20bes%C3%B8ksstans%20og%20sosial%20isolering%20under%20covid%2019-pandemien.pdf (downloaded 12.04.2022).

28. Minde G-T, Brustad A-K. Pandemien har økt omsorgsbyrden for mange pårørende til eldre. Sykepleien. 2021;109(84325):e-84325. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleiens.2021.84325

29. Cunningham M, Wells M. Qualitative analysis of 6961 free-text comments from the first National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in Scotland. BMJ Open. 2017 June;7(6):e015726. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015726

Comments