Family rooms in neonatal ICUs – registered nurses’ experiences

The organisational form results in RNs working in greater isolation, and this may mean that their professional competence stagnates. The parents become the experts on the child – not the RNs.

Background: Family-centred care in neonatal ICUs is a national and international trend that has received increasing attention and acceptance during the last decade. The idea of family-centred care arose from the so-called single room model, which entails more parental involvement in the care and treatment of premature and sick newborns. The single room or family room arrangement is designed to help ensure that parents stay with the hospitalised child at all times. The family room is thus the physical setting for the provision of family-centred care.

Objective: The study explores RNs’ experiences of family rooms.

Method: The study has an explorative descriptive design with three focus group interviews. The sample included thirteen informants who worked in a neonatal ICU. The data material was analysed using systematic text condensation.

Results: The analysis revealed two main themes: ‘Shift in the distribution of responsibility between parents and RNs’ and ‘Obstacles to nursing competence development and knowledge sharing’. The parents now become the experts on their own child, and it is the RNs who must ask the parents for information. This is a change from earlier when RNs had first-hand knowledge of the child and informed the parents. It was revealed that competence enhancement for RNs working in family rooms could stagnate because they work in greater isolation and have fewer opportunities to discuss nursing issues with other staff members.

Conclusion: This new method of organisation may be significant for RNs in the future. Family rooms will probably require higher staffing levels and more competence in the units. The professional development and training of new staff will also become more challenging since opportunities for knowledge transfer will be considerably reduced. For parents, family rooms will entail more responsibility earlier in the patient pathway.

The shift towards a more child- and family-friendly approach in neonatal care has gradually developed through a variety of care models that started to emerge at the end of the last century, such as Family-Centred Care (FCC) (1–3) and the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) (4). This has resulted in a transition to family rooms or single rooms. Research shows the importance of early attachment, and that the parents and child are not separated and the environment is adapted to the child’s development (5).

The 2017 guidelines from the Norwegian Directorate of Health (6) emphasise the importance of the parents’ role in the care team and of parents having as much contact with the child as possible. The child also has the right to have one of the parents by their side during the period of hospitalisation (7, 8). These guidelines also set out underlying principles for how Norwegian neonatal wards should be organised.

The RNs play a key role in the care team supporting the sick newborn or the premature child. These children are often extremely ill and need advanced intensive care – which requires a high level of competence among RNs. The RN is expected to have specialist competence and to be an expert, according to the Directorate’s definition (6).

The role of expert is developed through socialisation, education and experience. Norwegian neonatal ICUs include RNs with a bachelor’s degree or supplementary education as a paediatric nurse, an ICU nurse or neonatal nurse. The guidelines recommend a staffing profile with 60 per cent specialist competence (6).

Earlier research shows the differing experiences RNs have with FCC and the single room model, which involves including parents in the care team to the same extent as health personnel.

The RNs described challenges related to training and education in single rooms versus open units (9–10) and expressed concern due to a feeling of insecurity. They also found it more physically demanding and stressful with less interaction with colleagues (9). However, it appears that the stress they experienced in connection with single rooms was temporary and decreased over time (11), and that an FCC and single room model offered the child and their family more psychosocial support (11–12).

The RNs also reported that the single room model provided a better working environment (13–14). In a recent literature review about single rooms versus open units, the findings showed a mixture of positive and negative impacts in relation to the RNs’ work: better physical environment, qualitatively improved patient care and better job satisfaction. But collaboration in the care team was poorer and patient safety was reduced, while interaction with parents was reported both as better and as poorer (15).

Earlier research is limited, and it can be difficult to transfer the results of studies undertaken in other cultures to Norwegian conditions. As far as we know, no Norwegian studies have examined RNs’ experiences of working with the FCC and single room model.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to explore RNs’ experiences of family rooms. The research question was as follows:

‘What experiences do RNs have of caring for children and parents in family rooms compared with an open unit?’

Definition of family room

In this study, a family room is defined as a room in a unit where both parents can stay with the child 24 hours a day. The RNs can monitor the child via medical instruments. The parents are responsible for the care of the child, while the RN provides guidance and has the delegated medical responsibility. The family room is used in the transition from the hospital to the home.

Method

Design

The study has an explorative descriptive design inspired by an ethnomethodological research tradition. This entails methods that are suited to the study of the opinions and perceptions of the interviewees. The research object is the RNs in the focus group interview who communicate their expectations, opinions and rules related to the family room arrangement (16).

The data produced through the interviews are considered to represent meaningful and rational experiences that the RNs have gained through their work in the family room.

This is a qualitative study. We recruited RNs from a neonatal ICU at a Norwegian university hospital and interviewed them about their experiences of working in a family room. Based on the comprehensive dataset, the article sheds light on the RNs’ distribution of responsibility and knowledge development.

Data collection

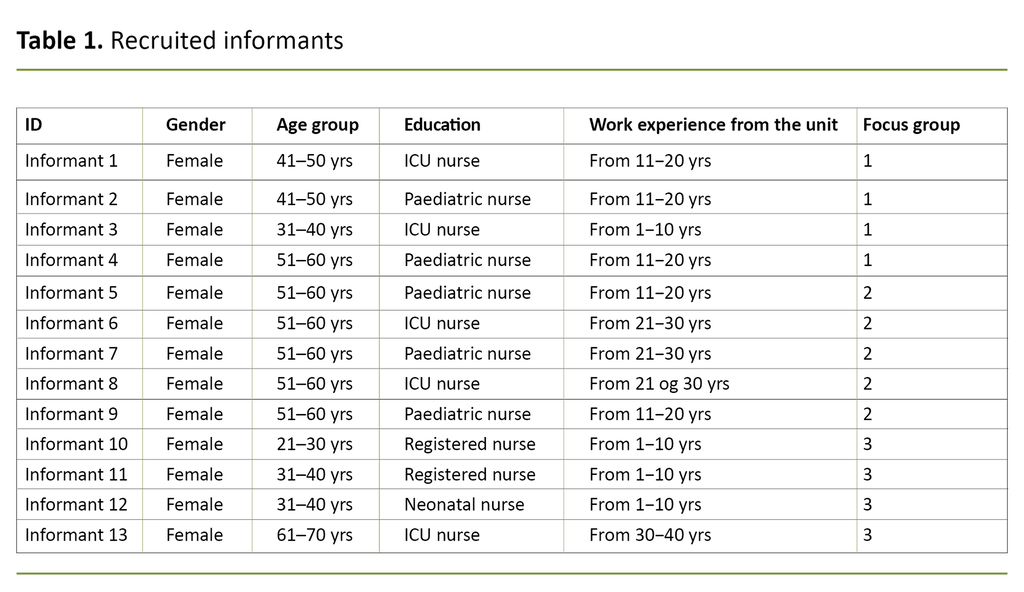

Empirical data that shed light on the research question were produced via three focus group interviews in which RNs and specialist nurses with over six months’ experience from a neonatal ICU were invited to participate. The sample, which was strategic, was recruited via researchers and approved by unit management. Thirteen RNs agreed to participate.

Table 1 gives an overview of the informants participating in the study. The interviews lasted 90 minutes on average, and the informants were divided into three groups in order to foster a group dynamic that would elicit more nuanced opinions and uncover more sensitive aspects of the topic (17).

We designed the interview guide on the basis of earlier research (10, 13, 15, 18), guidelines for family rooms and experiences from clinical practice. A pilot interview conducted at another hospital was used to adjust the questions (19). The informants were asked both open-ended and follow-up questions (17).

The first author carried out the interviews at the informants’ workplace in February and March 2019, and transcribed the audio recordings for further analysis.

Analysis

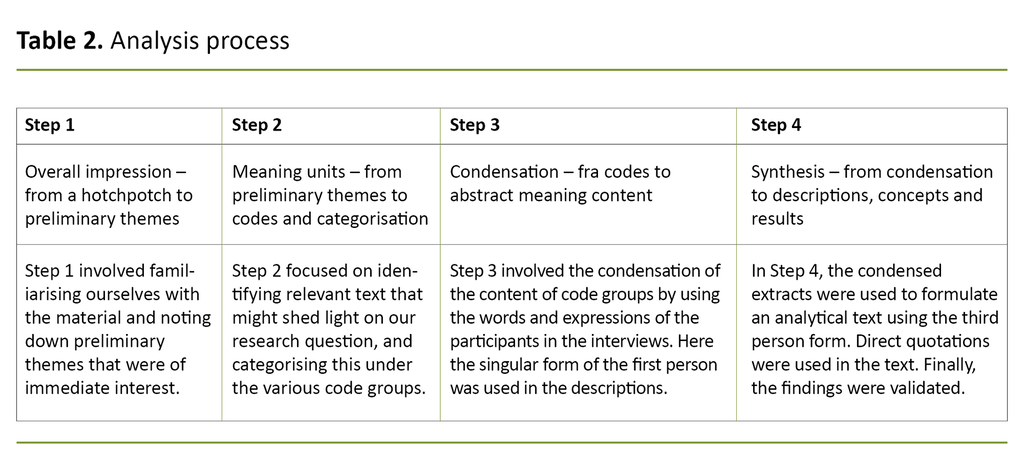

We performed a four-step inductive analysis, which forms the main structure of so-called systematic text condensation. First, we studied the text material to acquire an overall impression. Then we identified meaning units before abstracting the content of the individual units. Finally, we condensed the content of meaning in order to shed light on the research question (17, 20).

The analysis reveals two dominating themes in the transcribed data material. One theme concerns changes related to the child being moved from an open unit to a family room together with the parents. The second theme relates to the separation of RNs from the rest of the nursing staff when they work in family rooms.

Ethics

The study complies with the recommendations of the Helsinki Declaration, and we applied to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data for permission to conduct the study (case number 956190) and to the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC). The project was not subject to prior authorisation by REC.

Results

Shift in the distribution of responsibility between parents and RNs

The analysis showed that when the parents and child were moved to a family room, a shift occurred in the distribution of tasks and responsibilities between parents and RNs.

The underlying idea of the family room was discussed in one of the focus groups. Informant 5 said the following: ‘I think the philosophy underlying the provision of single rooms is typical of our culture. ‘We have to be alone’. Being alone was the main focus in both the advantages and disadvantages identified in the empirical material in terms of the organisation of nursing care and the RNs’ work situation.

The material showed that the RNs must now get information about the child from the parents as opposed to the situation earlier where the RNs had first-hand knowledge of the child and informed the parents. The informants found it challenging to enter into the private sphere represented by the family room even when this was agreed and when essential observations had to be performed.

The informants described how it was difficult to find their place. The concept of the family room has led to the establishment of practices and unwritten rules related to conduct. Informant 1 remarked as follows: ‘Before, it was the parents who came to visit the child and the RNs, now it’s the RNs who visit the parents’.

In the family rooms, the parents are encouraged and trained to take over the RN’s duties.

A family room was presented and described as if it were a home. Informant 8 described it as follows: ‘There’s something about the name of the room that allows people to drop their masks.’ The RNs regarded the family room as an opportunity for the family to have a private life. However, it is a paradox that there are no facilities to prepare food, wash clothes or have siblings stay overnight.

It is an unwritten rule that you knock on the door before entering the private sphere, and RNs do this before entering family rooms. This is a vastly different way of signalling your arrival and having contact with the parents compared to peering over a screen in an open unit, where the parents surround their baby’s incubator.

Staying in a family room also represents a shift in responsibility for caring for the child. In open units, it is the RNs who are responsible for the care and follow-up of the course of treatment. In the family rooms, the parents are encouraged and trained to take over the RN’s duties. Because all parents are assumed to be different, their perceptions and reactions to the organisational form and transfer of responsibility are also likely to differ.

Informant 3 cited the words of a mother as follows: ‘I didn’t choose to be a nurse, you did.’ This shows that this shift of responsibility may not necessarily be problem-free for everyone. One example illustrating the shift of responsibility was the task of tube feeding.

Obstacles to nursing competence development and knowledge sharing

The second theme concerned knowledge development and dissemination. Traditionally, RNs have learned from each other and discussed observations and nursing-related questions about the care of premature and sick newborns. Several informants were concerned about this. Informant 6 said: ‘We see each other when we arrive and when we leave’, indicating that there is a wide divide between the RNs who work in open units and those who work with the child and their parents in family rooms. There are few points of contact.

The material shows that those with least experience are given the most independent tasks. The informants asserted that less is expected of the RNs who work in a family room, which is why the least experienced among them are assigned this work.

The informants claimed that being responsible for the family room can make it difficult to have access to experienced RNs who are occupied with other tasks. When you have responsibility for the family room, you are often alone. Several informants found that there were few opportunities to interact with more experienced RNs when they needed help, guidance or supervision. They argued that this impeded professional development.

The material shows that those with least experience are given the most independent tasks.

The RNs working in the family room often work alone, and the parents themselves look after the child. This particularly impacts on RNs with little experience. It is difficult for the RNs to take part in the care and nursing of the child when the parents have moved into the family room and assumed responsibility. Informant 4 said the following: ‘We get to the point where we do not perform any care for the child.’

The RNs who mostly work alone also have no opportunity to observe how experienced RNs work and express themselves. They lose contact with their mentors. Informant 8 said the following: ‘Earlier, everything we did was visible. You heard everything, I learned everything, everything that was said during the first two years, I copied from someone else.’ This statement shows that the family room organisation may function as a barrier to the transfer of knowledge between RNs.

Informant 5 added the following: ‘It takes longer to acquire the same knowledge.’ RNs with little experience do not get access to the same opportunities to acquire knowledge when they have to work independently as those with more experience. Informant 10 described the antithesis of working on your own as follows: ‘Because I learned an awful lot when I started working with people with more experience, and that was really good.’

The empirical material shows that all RNs regardless of their experience felt that they lacked a meeting place for professional discussions. The family rooms, with the parents present, were unsuitable. The family room organisation prevented RNs from taking up and discussing nursing-related questions.

Informant 9 said: ‘I think we had more points of contact earlier to discuss nursing issues because you could talk about things as they came up. So there was a lot of nursing-related discussion, which is now disappearing because there’s a dead space between you and others.’ This statement indicates that this kind of organisation impedes conditions for knowledge sharing and nursing-related discussions.

Discussion

Being alone

The use of the family room entails putting in place a practice where both parents and RNs are on their own (9, 10). For the parents, this means more responsibility at a time that is often characterised by uncertainty and many questions. In addition, the parents are left on their own in a room with few opportunities to meet others or go out for a walk – a kind of isolation.

The RNs also talk about this isolation. When a baby is born prematurely or is sick, expectations of a harmonious post-natal period are replaced by constant uncertainty and worry (21), where there may be a need for close monitoring. Other studies also show that the parents need to be included and require individual follow-up (19, 22).

From the RNs’ perspective, they have sole responsibility in the family room.

From the RNs’ perspective, they have sole responsibility in the family room. It is often the least experienced RNs who are given this responsibility. When parents feel uncertain, it is vital that they encounter RNs who create a feeling of security and are knowledgeable and experienced. The combination of uncertain parents and RNs with little experience means that there is a danger of this being a case of ‘the blind leading the blind’. This practice is in contrast to political guidelines on competence requirements (6).

‘I didn’t choose to be a nurse, you did’

It is positive that the parents become experts on their own child and establish early contact (5). Nevertheless, the question arises as to whether the responsibilities imposed on the parents are too great, or whether RNs lose part of their responsibility.

When a mother says, ‘I didn’t choose to be a nurse, you did’, this indicates that the whole situation has become too much for her to deal with, and she wants the RN to take over more of the responsibility. The parents are not trained nurses. You do not expect the parents to replace an RN. However, we see that a lot of responsibility is being transferred to the parents (23).

The relationship between RNs and the child is different from that between the parents and the child. In neonatal care, we communicate by touch and adept handling. We assume that there is a difference between a mother caring for her child and a nurse caring for a patient. Therefore, the hands that touch the child are significant since the parents are the child’s key care providers (9, 10, 24).

The material shows that family room organisation versus open units raises the question of whether the nursing skills the parents acquire are good enough for them to take over the RNs’ tasks. Transferring all nursing care and responsibility to the parents means that it will take a long time for the RNs to become adept at using touch or that they may lose the skills they have already acquired.

A home in the hospital

The RNs describe the family room as a safe place where the parents can be themselves, drop their masks and give their emotions free rein. In this unit, the family room is used in the transition from hospital to home. The parents take over responsibility while help is never far away. The idea is to create a feeling of security before the parents return home.

At home, the parents will make arrangements with someone they know who can look after the child if they need a break. This is referred to as ‘respite’ in the data material. According to the informants, the expected practice is that the parents are relieved by friends and family as necessary when they move into the family room with the hospitalised child, not by RNs. Another study confirms that the parents are responsible for nursing care while the RNs are responsible for medical care (22).

Otherwise it appears that the RNs’ position is transformed from a professional role to that of a private actor. Despite clarification of what the parents’ tasks are and what the RNs’ tasks are, misunderstandings can still arise as to the scope of the respective responsibilities of parents and RNs.

Knowledge development stagnates in the family room

The informants in all focus groups expressed concern about competence enhancement. Since RNs work more independently in the family room, they do not see or hear what experienced RNs say and do. This view is supported in Coats’ article (10), which highlights how the open environment allows knowledge transfer among staff.

Since RNs work more independently in the family room, they do not see or hear what experienced RNs say and do.

The master-apprentice relationship between colleagues is important, particularly at the start of one’s working career (25). All groups argue that the professional relationship between newly qualified and experienced RNs is an important part of professional development. RNs copy both the words and actions of more experienced colleagues, and this helps to develop individual as well as collective knowledge and identity.

When building new hospitals in Norway, a key requirement is that patients are offered single rooms (26). This means that RNs will work even more independently and alone in the future. ‘Alone’ is a key word in this respect.

The informants emphasise that they can learn a lot on their own, both from their own successes and from self-study. But learning in peer groups in contextual situations is a unique and extremely valuable experience. The fact that the RNs work alone creates a situation where there is little possibility of guidance. Empirical data show that RNs are concerned about a lack of professional development as a result of the family room organisation.

We see each other when we arrive and when we leave

The RNs in this study describe the importance of job satisfaction and the opportunity to establish good relationships with colleagues, not only professionally. They said that socialising in the ward could be affected when the RNs more often work on their own in the family room. In turn, this can lead to fewer opportunities for social encounters and professional discussions internally, which will impact on professional development (25).

The analysis shows that professional development takes longer if you have to experience everything yourself. Personal experience may lead to greater independence, but it can also lead to insecurity. The RNs in the study call for nursing-related discussions in a staff setting, and this is difficult to achieve in the family room. Moreover, the lack of meeting points in the unit may make it difficult for RNs to create good relationships with each other.

Discussion of method

The study was conducted in the workplace of the first author. This may have influenced the analysis and discussion even though we attempted to distance ourselves from our own experiences. The credibility of the study is strengthened by its clear objective, and by the inclusion of direct quotations from the informants. Moreover, the moderator asked follow-up questions during the interviews, which further boosts the credibility of the study.

As a point of departure, we wanted to explore the experiences of both new nurses and experts in order to identify variations. However, we were only able to recruit a few RNs with limited experience.

Nevertheless, the composition of the group reflects the ward staff, where the majority had a high level of competence and many years’ experience – also from the time when the department consisted of open units. We felt that we had received answers related to the group’s shared experiences, attitudes and views in an environment in which different RNs interact to serve the best interests of the child and their parents (20).

Conclusion

This new organisational form will impact on RNs in the future. We are already seeing how the family room may require considerable resources and could promote an individualised work situation. Empirical data show that the current plan to only provide single rooms and family rooms will probably require higher staffing levels and more competence in the units.

Professional development and training for new members of staff will also pose a greater challenge in that opportunities for knowledge transfer will be considerably reduced. For the parents, this will entail more responsibility at an earlier stage of the patient pathway.

The article is based on a master’s thesis written by Sandra Kvamme and Berit Jensen. We have shared the work on the master’s thesis and the article equally, and we therefore wish to share first authorship.

References

1. Johnson BH. Family-centered care: four decades of progress. Families, Systems & Health. 2000;18(2):137–56. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091843

2. Harrison TM.Family centered pediatric nursing care: state of the science. Pediatric Nursing. 2010;25(5):335–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedn.2009.01.006

3. Gooding JS, Cooper LG, Blaine AI, Franck LS, Howse JL, Berns SD. Family support and family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit: origins, advances, impact. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(1):20–8. DOI: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.10.004

4. Als H, Gilkerson L. The role of relationship-based developmentally supportive newborn intensive care in strengthening outcome of preterm infants. Semin Perinatol. 1997;21(3):178–89. DOI: 10.1016/s0146-0005(97)80062-6

5. Griffiths N, Spence K, Loughran-Fowlds A, Westrup B. Individualised developmental care for babies and parents in the NICU: evidence-based best practice guideline recommendations. Early Hum Dev. 2019;139(104840):1–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104840

6. Helsedirektoratet. Nyfødtintensivavdelinger – kompetanse og kvalitet [Internet]. Helsedirektoratet; 09.05.2019 [updated 29.09.2017; cited 13.12.2020]. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/nyfodtintensivavdelinger-kompetanse-og-kvalitet

7. De forente nasjoner (FN). FNs konvensjon om barnets rettigheter. 20.11.1989. Oslo: Barne- og familiedepartementet; 1991. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/bfd/bro/2004/0004/ddd/pdfv/178931-fns_barnekonvensjon.pdf (downloaded 14.10.2021).

8. Forskrift 1. desember 2000 nr. 1217 om barns opphold i helseinstitusjon. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2000-12-01-1217 (downloaded 24.09.2021).

9. Walsh WF, McCullough KL, White RD. Room for improvement: nurses’ perceptions of providing care in a single room newborn intensive care setting. ADV Neonatal Care. 2006;6(5):261–70. DOI: 10.1016/j.adnc.2006.06.002

10. Coats H, Bourget E, Starks H, Lindhorst T, Saiki-Craighill S, Curtis JR, et al. Nurses' reflections on benefits and challenges of implementing family-centered care in pediatric intensive care units. American Journal of Critical Care. 2018;27(1):52–8. DOI: 10.4037/ajcc2018353

11. van den Berg J, Bäck F, Hed Z, Edvardsson D. Transition to a new neonatal intensive care unit. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2017;31(1):75–85. DOI: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000232

12. Winner-Stoltz R, Lengerich A, Hench A, O'Malley J, Kjellans K, Teal M. Staff nurse perceptions of open-pod and single family room NICU designs on work environment and patient care. Advances in Neonatal Care. 2018;18(3):189–98. DOI: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000493

13. Bosch S, Bledsoe T, Jenzarli A. Staff perceptions before and after adding single-family rooms in the NICU. HERD. 2012;5(4):64–75. DOI: 10.1177/193758671200500406

14. Stevens DC, Helseth CC, Khan MA, Munson DP, Smith TJ. Neonatal intensive care nursery staff perceive enhanced workplace quality with single-family room design. Journal of Perinatology. 2010;30(5):352–8. DOI: 10.1038/jp.2009.137

15. Doede M, Trinkoff AM, Gurses AP. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit layout and nurses’ work. HERD. 2018;11(1):101–18.DOI: 10.1177/1937586717713734

16. Garfinkel H. Ethnomethodology's program. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1996;59(1):5–21. DOI: 10.2307/2787116

17. Malterud K. Kvalitativ forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

18. Shahheidari M, Homer C. Impact of the design of Neonatal Intensive Care Units on neonates, staff, and families: a systematic literature review. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2012;26(3):2606. DOI: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e318261ca1d

19. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups. 5th ed. London: Sage Publications; 2015.

20. Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. 3rd ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2012.

21. Dolleus J, Janson C. Föräldrars upplevelse av att samvårda sitt barn på familjerum på neonatalvårdsavdelning [Master's thesis]. Halmstad: Högskolan i Halmstad, Akademin för Hälsa och Välfärd; 2018. Available at: http://hh.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1220412/FULLTEXT02.pdf (downloaded 10.03.2021).

22. Fergan L, Helseth S. The parent-nurse relationship in the neonatal intensive care unit context-closeness and emotional involvement. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2015;23(4):667–73. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00659.x

23. Sundal H, Petersen A, Boge J. Foreldre utfører mesteparten av pleien og omsorgen ved barnets korte sykehusopphold. Klinisk Sygepleje. 2018;32(2):80–93. DOI: 10.18261/issn.1903-2285-2018-02-02

24. Roué JM, Kuhn P, Maestro ML, Maastrup RA, Mitanchez D, Westrup B, et al. Eight principles for patient-centred and family-centred care for newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2017;102(4):364–8. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312180

25. Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. Mesterlære og ekspertenes læring. In: Nielsen K, Kvale S, eds. Mesterlære: læring som sosial praksis. Oslo: Ad Notam Gyldendal; 1999. pp. 61–3.

26. Helse Stavanger, Stavanger universitetssjukehus. Fakta om nytt universitetssykehus [Internet]. Stavanger: Helse Stavanger, Stavanger universitetssjukehus 04.11.2016 [updated 27.04.2020; cited 13.12.2020]. Available at: https://helse-stavanger.no/om-oss/nye-sus/fakta-om-nytt-universitetssykehus

Comments