Living with pain in adolescence – a qualitative study of young people’s experiences

They link their pain to stress and pressures in their everyday lives, particularly associated with schoolwork. Many are unsure of what to do to cope with pain.

Background: Pain is a major health concern and increasing numbers of adolescents experience persistent pain. More girls than boys are affected. Living with pain affects a person’s quality of life and is related to sleeplessness, stress, depression, and absence from school. For many, the pain becomes severe and persistent, lasting into adulthood.

Objective: To describe how young people experience living with persistent pain, how this affects their everyday life and schoolwork, and what they themselves are doing to cope with their pain.

Method: The study has a qualitative design and is based on individual interviews with seven adolescents with persistent pain.

Results: One of the study’s main findings was that the young people experienced a great deal of stress and pressure in their everyday lives, and that they generally linked their pain to this strain. Stress associated with school and schoolwork was of particular concern. The informants did not wish to be absent from school because of their pain, and most of them were not talking to anybody about these problems. The results also showed that most of the informants had no effective strategy for coping with pain.

Conclusion: The young informants felt a lack of support and found that they had insufficient information and inadequate strategies for coping with pain. Because pain can have serious consequences in the short and long term, it is important that health promoting efforts emphasise pain prevention and strategies for coping with pain, to stop the pain from becoming chronic or persistent. Public health nurses are familiar with ways of coping with pain and stress and have an important role to play in giving information to children and their parents and providing guidance for adolescents in how to cope with pain.

The prevalence of pain differs considerably between studies, but between 15 and 35 per cent of all children and adolescents experience persistent pain (2, 3, 5, 6).

Results from the 2017 Norwegian municipal youth survey Ungdata showed that 20 per cent of students in upper secondary school had experienced pain on a daily basis in the previous month (7).

Studies also show that the most common types of pain are headache, shoulder and neck pain, stomach ache, and joint and muscle pain, and that pain is more commonly reported by girls than boys (3, 8–10). The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (11) reports that pain is one of the most common causes of long-term incapacity to work and health loss in adults.

Pain is a complex and complicated problem that impacts significantly on a young person’s life (3, 12, 13). Pain that lasts for more than three months is often defined as either persistent or chronic (1).

Living with persistent pain causes absence from school and social activities, anxiety, and sleeplessness (8, 14–16). Studies show that adolescents who experience pain, have a reduced quality of life compared to adolescents who are pain free (3, 17).

Some adolescents will find that their pain will pass, but for many the problem will become serious and persistent, lasting into adulthood (18, 19). Although our current knowledge about pain has improved, we know little about young people’s own experience of living with such challenges.

A qualitative study showed that adolescents who were living with pain felt socially excluded because their pain meant that they were no longer able to take part in the social activities they used to be involved in (20). Another qualitative study showed that adolescents with chronic pain used various coping strategies, and these were largely influenced by family, friends, and attitudes to pain (21).

Adolescence is a vulnerable period in life, but also a time when young people accept more responsibility for their own health. A new study points out that pain in adolescents is an under-studied phenomenon, and that there is a need for more knowledge about young people’s experiences and pain prevention among this group (6).

The study’s objective

It is important to learn more about young people’s own experiences to enable the development of effective initiatives that will prevent pain and promote coping. This study’s objective is therefore to describe how adolescents experience living with persistent pain, how it affects their everyday lives and school situation, and what the young people themselves are doing to cope with the pain.

Method

Design

We used a qualitative descriptive design. The method of data collection was individual interviews with adolescents with persistent pain.

Sample

We invited adolescents from five different upper secondary schools to take part in the study. The schools were all located in the same municipality. The inclusion criteria were adolescents aged between 16 and 19 who had experienced persistent and/or chronic pain every week for three months or more, based on their subjective self-reporting.

Exclusion criteria were adolescents who were experiencing pain that could be related to diagnoses such as cancer. It was a requirement that all informants were able to read and understand Norwegian. Nine adolescents wanted to take part in the study, but two of them failed to attend the interview. The final sample consisted of seven adolescents with an average age of 17 years (Table 1).

Recruitment

Informants were recruited in parallel with participants for a PhD project entitled ‘iCanCope with Pain’, a study of pain and coping with pain in adolescents (17).

Following the approval of the study by the county’s Head of Education and the respective upper secondary schools, we arranged with individual teachers when to come and talk to their classes. The public health nurse at the school was informed about the study and helped with the recruitment of informants.

The first author visited the classrooms with the second author (who was working on the ‘iCanCope with Pain’ project) to provide information about the studies. The young people were given written and oral information about the study, and they had an opportunity to ask questions.

They were asked to contact us by email if they wanted to take part in the qualitative project, in the PhD project, or both. Once they had made contact, a consent form and an information letter were forwarded to them.

Implementation and data collection

Once the informants had made contact via email, a time and place were agreed for the interviews. The first author conducted the interviews in a meeting room at the university. One of the interviews was conducted in a café on the informant’s request.

We had prepared a semi-structured interview guide consisting of a few main questions, each with a set of sub-questions. The interview guide was based on literature about pain as well as results from earlier studies (1–3).

We started each interview by asking the informant to talk a little about themselves, their age, year at school, and their chosen education programme. The interview guide consisted of the following main questions:

- Could you tell us a little about your pain?

- Please tell us how pain affects your daily life?

- How does the pain affect your school situation and your schoolwork?

- Please tell us what you do to cope with the pain?

Each interview lasted 40–60 minutes and they were all recorded electronically before being transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

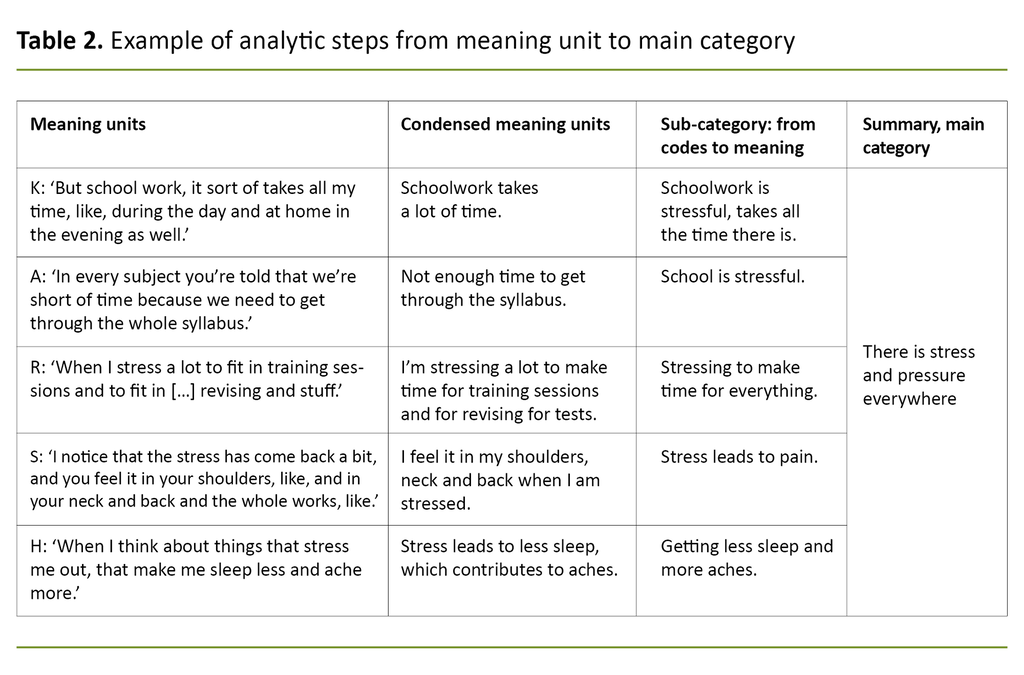

We conducted the analysis using systematic text condensation as described by Malterud (22). We started by reading all the interview transcripts several times, to familiarise ourselves with the data material. This allowed us to form an overall impression and to discuss preliminary themes.

The next step involved identifying and sorting meaning units from themes to codes. At step three, we simplified the selected segments, and in the last step of the analysis we synthesised all the parts of the text (re-contextualisation) and formulated the main categories.

The analysis was conducted by the first author in collaboration with the last author. We made use of the NVivo analytic software to collate the material. See an example of the analytic steps in Table 2.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) and Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) as a part of the ‘iCanCope with Pain’ project (REK number: 2017/350).

We obtained the informants’ informed consent in writing before the interviews started and we preserved their anonymity and kept their data confidential. Participants were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving any reason for doing so.

The authors’ background and pre-understanding

The first author is a registered nurse with experience of pain-related issues. The second author is a physiotherapist and associate professor, and the last author is a registered nurse and professor. All authors draw on previous experience of research associated with young people and pain, and this has formed part of our pre-understanding.

Results

Fictitious names have been used in the presentation of all findings. All informants contributed to the study’s results. The description of the sample (Table 1) shows that all the young informants experienced pain several time a week, three of them experienced pain every day, and the majority had experienced pain over a period of two years or more.

By analysing the interview data, we identified the following main categories: ‘There is stress and pressure everywhere’, ‘Not wanting to be absent from school because of pain’, ‘Not talking about their pain’, and ‘It is difficult to know what to do when in pain.’

There is stress and pressure everywhere

All the young people who took part in the study experienced stress and pressure in their daily lives, particularly in relation to their school situation and their schoolwork. Most of them said that one of the main causes of their pain was stress and the demands that were put on them by themselves and others: ‘I notice that the stress has come back a bit, and you feel it in your shoulders, like, and in your neck and back and the whole works, like’ (Per).

Demands to do well at school came from teachers and friends, as well as from parents.

The young informants talked about the many demands placed on them by the school and explained that they spent much time and energy on doing schoolwork. Demands to do well at school came from teachers and friends, as well as from parents.

Most of the young informants talked about being anxious to achieve good grades and to do well at school: ‘Well, ever since I was a little girl, I’ve been told that unless I go to university and get a master’s degree and become a professor, my life will be a failure’ (Marit).

The young people had found the transition to upper secondary school difficult, and they experienced more stress and pressure in upper secondary school than in lower secondary school.

Not wanting to be absent from school because of pain

Going to school was important to the young informants. They explained that they avoided being absent from school as far as possible, even if they were in pain. Several talked about going to school despite being in pain and feeling ill. They considered the limit on unauthorised absence to be too strict.

‘And when it’s a tummy ache, you know, I sometimes can’t […] sometimes I can feel like going home, but I don’t. Because of that absenteeism stuff’ (Inger).

‘My whole life is about school. For that’s what I care about, in a way’ (Marit).

The young informants also explained that they wanted to attend school because they wished to be ‘like everybody else’. It was important to them to fit in and not be different. But several talked about having quit leisure activities, and that they often had to miss out on social activities because of their pain.

Not talking about their pain

It was common among the informants not to talk about their pain with friends or anyone else because they worried about being seen as ‘different’. Some were worried that others would see them as ‘whingers’.

Only two of the informants had talked to a public health nurse about the pain, while some had talked to their parents and friends about it. Virtually no informants believed that anybody else knew how they felt.

‘But as soon as they get too close, or people that see me every day, like, I hate talking about it because I feel that they start treating me different straight away. Or they look at me, like ‘oh no, poor you’, and then that’s how it goes’ (Anne).

Several informants explained that one of the most difficult things about pain was that it was not apparent to anybody else.

Several informants explained that one of the most difficult things about pain was that it was not apparent to anybody else. They had all experienced not being believed when in pain, and they had found that others thought they used pain as an excuse whenever they wanted to get out of doing something.

This was part of the reason why they had no wish to talk to anybody about their pain. ‘Not necessarily just that they don’t believe you, but that they think less of you, perhaps’ (Per).

It is difficult to know what to do when in pain

The young people had adopted different strategies for coping with their pain, but the majority explained that they did not know what to do to make things better. Most of the informants said that they wanted someone to talk to, but that they did not know who to contact. Some of them felt that there was nothing much that they themselves could do about the cause of the pain.

‘But stress, there’s not a lot I can do about it. I can’t change anything, it’s the school that needs to change. It’s the school that causes it.’ (Inger).

Only two informants said they tended to take painkillers when in pain. Several had found that physical exercise was a way of coping, and most of the young people attended regular training sessions. Some explained that they felt it was important to train several times a week, while others said it was important to sleep and relax whenever they felt pain.

Discussion

One of the study’s main findings was that the young informants experienced much stress and pressure in their everyday lives, and that they generally linked their pain to these strains. These were particularly associated with their school lives and schoolwork. Many adolescents find that everyday stresses and pressures manifest as a physical affliction, and that pain is a symptom of this (20, 23).

Other studies have also showed that adolescents consider stress to be an important cause of pain (12, 21). One study demonstrated a link between pain and stress among adolescents and showed that this link is equally strong among boys and girls (23).

The fact that the adolescents themselves associate their pain with feeling stressed, is an important finding because knowledge about what may cause pain, is key to prevention and the promotion of coping strategies (6, 17, 24).

Pain impacts on their social lives

The young people in our study explained that their pain had an impact on their social lives and their school day. Other studies have also showed that pain affects everyday life at school and can be linked to absence from school (25, 26).

The young informants also explained that schoolwork was often stressful, and that there were many demands associated with their school life. The 2017 NOVA Report showed that school-related stress is associated with constant performance pressures in the day-to-day, as well as a more long-term pressure to get a good education. The report discusses whether work pressures and performance expectations at school may be associated with increased psycho-social health problems among adolescents (7).

Most of the young informants did not talk about their pain with anybody, whether family, friends, teachers, or a public health nurse.

Another important finding of our study is that most of the young informants did not talk about their pain with anybody, whether family, friends, teachers, or a public health nurse. The fact that adolescents do not talk about their pain, has also been demonstrated in other studies (8, 20, 27, 28).

One Norwegian study showed that parents are often not aware of their children’s pain (8). This is worrying, because the help and support that they need may therefore not be made available to them. Some also stated that they did not want to talk about their pain because they feared not being believed.

Studies have found that some adolescents who talk to others about the pain they feel, are met with disbelief (27). Pain is a subjective sensation which is invisible to everybody else, and this makes it difficult to talk about with others (20, 27).

Only some of the young informants in our study reported using painkillers to cope with the pain. However, several explained that rather than actively seeking to remove or change the problem, they distanced themselves from it or did not know what to do to cope with the pain.

Young people need more knowledge about pain and stress

It appears that adolescents lack effective strategies to cope with pain, and that they need more knowledge about how to cope with pain and stress (5, 27). Many of our young informants appeared to take a passive approach to coping with their pain.

Several put the blame on factors beyond their control and felt there was little they could do about it. Other studies have shown that adolescents are often at a loss to know where to seek information about pain or how to cope with the problem (27).

Studies have shown that a lack of effective coping strategies can contribute to prolonging and intensifying the feeling of pain (6, 12). The results of our study showed that it was important for the young people to fit in, but that their pain made them feel that they were different.

Pain had caused some of the young informants to quit leisure activities and it made them spend less time with friends. Earlier studies also show that pain can make adolescents feel that they are different, and for some, this means that they isolate themselves from friends and social activities (8, 20).

Public health nurses can provide information

Adolescence is a vulnerable stage in life, but it is also a time when young people take on more responsibility for their own health and can develop positive health behaviours and coping strategies (19).

All children attend check-ups with public health nurses throughout their childhood and adolescence. The public health nurses have an important role to play in discovering pain, providing information and taking preventive measures (29).

Children and adolescents who experience persistent pain, have a greater risk of developing additional problems such as depression and anxiety in adulthood.

Children and adolescents who experience persistent pain, have a greater risk of developing additional problems such as depression and anxiety in adulthood (6, 30–32). It is therefore important to focus on prevention.

Palermo accentuates the importance of focusing on pain and pain prevention in health promotion and proactive efforts. This work needs to start early in life to ensure that children and adolescents do not develop persistent and chronic pain (6).

The study’s strengths and weaknesses

To strengthen the study’s credibility, we have emphasised transparency in our choice of methodology and approach, describing the research process in detail. The study’s findings cannot be generalised, but they are especially relevant to the health service in general, and to public health nurses who work with children and young people in particular.

There is a risk that researchers and informants do not share a common understanding of the terminology that is used in an interview (22). We tried to mitigate this risk by asking clarifying and confirming questions along the way. This was done to validate our interpretation of what was being said.

Seven young people took part in the study. They talked freely about the theme and gave detailed descriptions. Pain is a complex phenomenon, and its assessment can be influenced by one’s cultural background, as can one’s coping strategies. All informants in this study are ethnically Norwegian. Only two boys took part, and all informants attended education programmes that would qualify them for higher education. It would have strengthened the study further if our sample had included a more diverse mix of adolescents.

Conclusion

Pain has an impact on the young people’s lives and school days. Our informants generally associated pain with a feeling of stress and pressure, particularly in a school context. Many were uncertain how to deal with their pain and felt a lack of support and effective coping strategies.

Because pain can have severe consequences for young people and their families in both the short and longer term, it is important that health promotion and proactive efforts focus on pain prevention and coping strategies, to prevent the pain becoming chronic or persistent.

Public health nurses have knowledge about ways of coping with pain and stress and have an important role to play in keeping children and their parents informed and providing guidance for adolescents in coping with pain. There is a need for more research in this field.

Longitudinal studies will be important in order to investigate how pain develops over time, as well as intervention studies that focus on coping with pain.

References

1. de la Vega R, Groenewald C, Bromberg MH, Beals-Erickson SE, Palermo TM. Chronic pain prevalence and associated factors in adolescents with and without physical disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(6):596–601. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.02.161

2. Gobina I, Villberg J, Välimaa R, Tynjälä J, Whitehead R, Cosma A, et al. Prevalence of self-reported chronic pain among adolescents: evidence from 42 countries and regions. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(2):316–26. DOI: 10.1002/ejp.1306

3. Haraldstad K, Christophersen KA, Helseth S. Health-related quality of life and pain in children and adolescents: a school survey. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):174. DOI: 10.1186/s12887-017-0927-4

4. Hoftun GB, Romundstad PR, Zwart JA, Rygg M. Chronic idiopathic pain in adolescence – high prevalence and disability: the young HUNT Study 2008. Pain. 2011;152(10):2259–66. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.05.007

5. Ottová-Jordan V, Smith OR, Gobina I, Mazur J, Augustine L, Cavallo F, et al. Trends in multiple recurrent health complaints in 15-year-olds in 35 countries in Europe, North America and Israel from 1994 to 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25 Suppl 2:24–7. DOI: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv015

6. Palermo TM. Pain prevention and management must begin in childhood: the key role of psychological interventions. Pain. 2020;161 Suppl 1(Suppl):S114–S21. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001862

7. Bakken, A. Ungdata 2018, Nasjonale resultater. NOVA report 8/18.

8. Haraldstad K, Sørum R, Eide H, Natvig GK, Helseth S. Pain in children and adolescents: prevalence, impact on daily life, and parents' perception, a school survey. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25(1):27–36. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00785.x

9. Harker J, Reid KJ, Bekkering GE, Kellen E, Bala MM, Riemsma R, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain in Denmark and Sweden. Pain Res Treat. 2012;371248. DOI: 10.1155/2012/371248

10. King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152(12):2729–38. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016

11. Knudsen AK, Øverland S, Vollset SE, Kinge JM, Skirbekk V, Tollånes MC. Sykdomsbyrde i Norge 2016. Resultater fra Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2016 (GBD 2016). Rapport FHI. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2015/sykdomsbyrde_i_norge_2015.pdf (downloaded 06.09.21).

12. Kalapurakkel S, Carpino EA, Lebel A, Simons LE. «Pain can't stop me»: examining pain self-efficacy and acceptance as resilience processes among youth with chronic headache. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(9):926–33. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu091

13. Hoftun GB, Romundstad PR, Rygg M. Factors associated with adolescent chronic non-specific pain, chronic multisite pain, and chronic pain with high disability: the Young-HUNT Study 2008. J Pain. 2012;13(9):874–83. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2021.06.001

14. Palermo TM, Valrie CR, Karlson CW. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: a developmental perspective. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):142–52. DOI: 10.1037/a0035216

15. Wilson AC, Holley AL, Stone A, Fales JL, Palermo TM. Pain, physical, and psychosocial functioning in adolescents at risk for developing chronic pain: a longitudinal case-control study. J Pain. 2020;21(3–4):418–29. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.08.009

16. Badawy SM, Law EF, Palermo TM. The interrelationship between sleep and chronic pain in adolescents. Curr Opin Physiol. 2019;11:25–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.cophys.2019.04.012

17. Grasaas E, Helseth S, Fegran L, Stinson J, Småstuen M, Haraldstad K. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with persistent pain and the mediating role of self-efficacy: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):19. DOI: 10.1186/s12955-020-1273-z

18. Sylwander C, Larsson I, Andersson M, Bergman S. The impact of chronic widespread pain on health status and long-term health predictors: a general population cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2020;21(1):36. DOI: 10.1186/s12891-020-3039-5

19. Eckhoff C, Straume B, Kvernmo S. Multisite musculoskeletal pain in adolescence as a predictor of medical and social welfare benefits in young adulthood: the Norwegian arctic adolescent health cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2017;21(10):1697–706. DOI: 10.1002/ejp.1078

20. Sørensen K, Christiansen B. Adolescents' experience of complex persistent pain. Scand J Pain. 2017;15:106–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.02.002

21. Skarstein S, Lagerløv P, Kvarme LG, Helseth S. High use of over-the-counter analgesic; possible warnings of reduced quality of life in adolescents – a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2016;15:16. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-016-0135-9

22. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin- og helsefag. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

23. Østerås B, Sigmundsson H, Haga M. Pain is prevalent among adolescents and equally related to stress across genders. Scand J Pain. 2016;12:100–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.05.038

24. Miró J, Castarlenas E, de la Vega R, Galán S, Sánchez-Rodríguez E, Jensen MP, et al. Pain catastrophizing, activity engagement and pain willingness as predictors of the benefits of multidisciplinary cognitive behaviorally-based chronic pain treatment. J Behav Med. 2018;41(6):827–35. DOI: 10.1007/s10865-018-9927-6

25. Groenewald CB, Giles M, Palermo TM. School absence associated with childhood pain in the United States. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(6):525–31. DOI: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000701

26. Groenewald CB, Tham SW, Palermo TM. Impaired school functioning in children with chronic pain: a national perspective. Clin J Pain. 2020;36(9):693–9.

27. Fegran L, Johannessen B, Ludvigsen MS, Westergren T, Høie M, Slettebø Å, et al. Experiences of a non-clinical set of adolescents and young adults living with persistent pain: a qualitative metasynthesis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e043776. DOI: 10.21203/rs.2.16592/v1

28. Fisher E, Heathcote LC, Eccleston C, Simons LE, Palermo TM. Assessment of pain anxiety, pain catastrophizing, and fear of pain in children and adolescents with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43(3):314–25. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsz103

29. Kvarme LG, Haraldstad K, Helseth S, Sørum R, Natvig GK. Associations between general self-efficacy and health-related quality of life among 12-13-year-old school children: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:85. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-85

30. Mundal I, Gråwe RW, Bjørngaard JH, Linaker OM, Fors EA. Prevalence and long-term predictors of persistent chronic widespread pain in the general population in an 11-year prospective study: the HUNT study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:213. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2472-15-213

31. Hoftun GB, Romundstad PR, Rygg M. Association of parental chronic pain with chronic pain in the adolescent and young adult: family linkage data from the HUNT Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(1):61–9. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.422

32. Holstein BE, Andersen A, Denbaek AM, Johansen A, Michelsen SI, Due P. Short communication: Persistent socioeconomic inequality in frequent headache among Danish adolescents from 1991 to 2014. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(5):935–40. DOI: 10.1002/ejp.1179

Comments