Recruitment to the Cardiac Rehabilitation Programme – a random effort or a sound health education measure?

Recruitment to the Cardiac Rehabilitation Programme seems to be somewhat random and ‘the main concern is to get the patients on the list’. Health professionals should communicate better among themselves and prepare guidelines for recruitment.

Background: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the disease groups that causes the most fatalities in Norway. According to Meld. St. 19 (2018–2019) The Public Health Report, Norway has aligned itself with the World Health Organization’s goal to reduce the number of people who die from non-communicable diseases such as CVD by 30 per cent by 2030. To achieve this goal, health education measures are crucial. The Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) Programme is a health education measure or training programme for patients who have had CVD. Studies have shown that participation in CR reduces morbidity, improves quality of life and has socioeconomic benefits. Despite the conclusions in these studies, there are no national guidelines requiring Norwegian hospitals to provide CR. This results in variable rehabilitation services, which in turn can affect patients’ ability to take care of their own health. Statistics from the hospital in this study show that some 400 patients participate each year in the CR Programme, while the number hospitalised with CVD is much higher. Therefore, it was of interest to investigate health professionals’ reflections on the recruitment of patients to the programme.

Objective: The study sought to gain knowledge about how health professionals recruit patients to the CR Programme and to elicit their reflections and reasoning related to recruitment.

Method: The design is descriptive and exploratory. The qualitative method was used to collect data from eight semi-structured interviews. One doctor, three physiotherapists and four registered nurses were interviewed, and a systematic text condensation was conducted as part of the analysis.

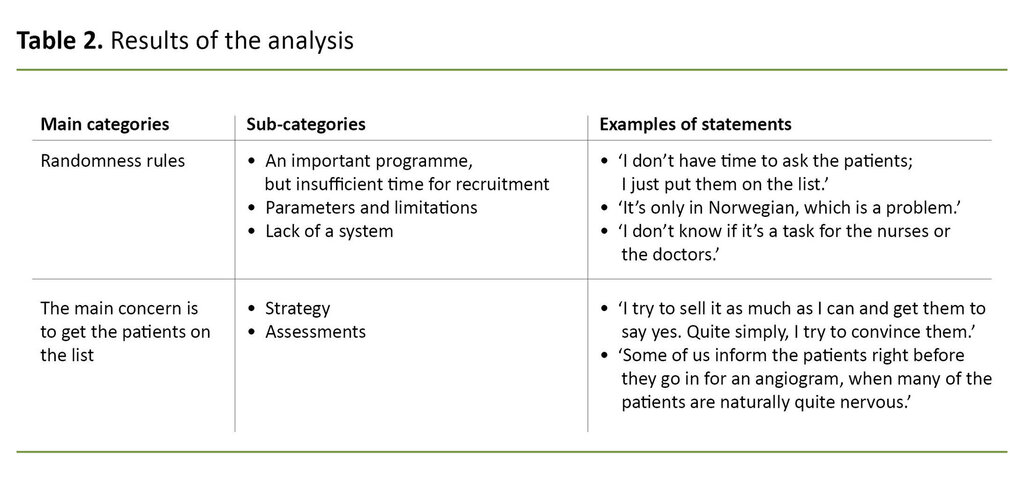

Results: The analysis resulted in two main categories and five sub-categories. The main categoryRandomness rules has the sub-categories‘An important programme, but insufficient time for recruitment’, ‘Parameters and limitations’ and ‘Lack of a system’. The main category The main concern is to get the patients on the list has the sub-categories ‘Strategy’ and ‘Assessments’.

Conclusion: The study identified challenges related to recruitment to the CR Programme. The results show that recruitment seems to be somewhat random and that ‘the main concern is to get the patients on the list’. Consequently, a system and guidelines for recruitment may need to be developed. Communication among the health professionals about how recruitment should be conducted may be helpful. To further develop the programme, it may be beneficial for health professionals who recruit patients to acquire competence in health education through training or practice.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an umbrella term for diseases of the heart and blood vessels. Each year, about 40 000 patients are treated for CVD in Norwegian hospitals. In addition, a higher prevalence of CVD is expected due to the increasing number of elderly among the population and higher survival rates (1).

According to Meld. St. 19 (2018–2019) The Public Health Report, Norway has aligned itself with the World Health Organization’s goal to reduce the number of people who die from non-communicable diseases such as CVD by 30 per cent by 2030 (2).

The Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) Programme provides health education or training to patients with CVD who have been hospitalised (3). The CR Programme offers exercise, discussion groups and instruction on a day-patient basis. All patients must be given equal access to the measure (4).

Cardiac rehabilitation is defined as ‘the sum of activities and interventions required to ensure them [patients with chronic or post-acute heart disease] the best possible physical, mental and social conditions so that they may, by their own efforts, resume and maintain as normal a place as possible in the community’ (5).

Health professionals must have competence in health education in order to achieve the CR Programme’s goal of patient education in the specialist health service and to satisfy the requirement set out in the Public Health Report (2). Health education facilitates patient education through interaction so that patients can successfully manage their own health challenges.

This is a priority area for the Norwegian government, which has prepared a strategy for bolstering health competence among the population. Health competence is defined as a person’s ability to understand, assess and apply health information in order to make knowledge-based choices about their own health (6).

Patient education can be seen in light of empowerment thinking, which involves a redistribution of power – from medical expert to patient, patient involvement and a view of patients as experts in their own health (6). Participation in the CR Programme can help patients to feel they have power over their own lives, which in turn can improve their quality of life (7).

Patient education can be essential for the ability of patients to take part in decisions about their own lives and health, which is a condition for empowerment (6, 7). In our study, we put the spotlight on recruitment to the CR Programme.

According to the Norwegian Patients’ and Users’ Rights Act (8), patients have a right to the information they need to take care of their own health. This information must be adapted to the patient’s individual circumstances (8).

The 2018 Congress of the European Society of Cardiology declared that CR referrals must be easy to carry out. All cardiac patients should receive an unqualified recommendation and be referred in a systematic manner (9). Despite the recommendations on systematic referrals, Grace et al. (10) found that this did not result in higher participation.

Studies have shown that participation in CR reduces morbidity, improves quality of life and has socioeconomic benefits (11–16). Despite the conclusions in these studies, Norway does not have national guidelines that require Norwegian hospitals to provide CR.

As of today, 30 health trusts in Norway offer day-patient CR programmes, but the content of these has not been standardised. This means that both the content of the programmes and access to them vary, and this can affect participation in the programmes as well as their efficacy (17).

On a nationwide basis, less than 30 per cent of CVD patients in Norway take part in CR, but the percentage of participation varies within the country (18). Studies show that patients with the most to gain by participating in learning and mastery programmes – those with a low level of education and low socioeconomic status – are not necessarily the ones who take part (19).

The most common reasons that patients do not participate are that they have not received a referral and they lack knowledge and information about the programme. Despite an increase in the number of referrals, 19 per cent of patients hospitalised for CVD are still not referred to CR (20).

Therefore, it is of interest to gain insight into health professionals’ reflections and reasoning related to the recruitment of patients to the CR Programme.

Objective of the study

The study sought to gain knowledge about how health professionals recruit patients to the CR Programme and to elicit their reflections and reasoning related to recruitment. This knowledge can form the basis for strengthening recruitment and thus possibly help more patients to acquire health competence should they need it.

Research question

- How do health professionals recruit patients to the CR Programme, and what are their reflections and reasoning related to recruitment?

Method

Design

The study used the qualitative method with a descriptive and exploratory design. We used hermeneutic principles (pre-understanding–understanding, part–whole, context and history) in our analysis and interpretation of text.

At project start-up, the Learning and Mastery Centre at Akershus University Hospital and Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) appointed a reference group consisting of two full professors and an associate professor from OsloMet, two registered nurses (RNs), a physiotherapist from the research community (a hospital in south-eastern Norway) and a user representative from the Norwegian National Association of Heart and Lung Disorders.

The user representative had experiential knowledge as a participant in the CR Programme after developing heart disease. The reference group provided feedback on the research questions, analysis and preliminary results.

Data collection

The data were derived from eight semi-structured interviews. The method was chosen based on the study’s objective, which was to acquire thorough, detailed descriptions of health professionals’ reflections, reasoning and practices related to the recruitment of patients to the CR Programme (21).

The research arena consisted of two cardiac wards at a hospital in south-eastern Norway. The researchers were invited by the health personnel of the hospital’s Learning and Mastery Centre to study recruitment to the CR Programme. The purpose was to find out who participates and who does not.

The informants were strategically selected because they were health professionals who recruited patients to the CR Programme but were not associated with it in other ways. The head of the cardiac ward helped the researchers to make contact with the informants.

Inclusion criteria were a completed bachelor’s degree in health sciences or a degree in medicine and a minimum of one year’s experience from a cardiac ward. The informants were women and men of various ages with a health sciences or medical background. In qualitative samples, shared experiences are given more weight than the sample size, and the sample consisted of health professionals from two cardiac wards who recruit patients (22).

The lead author conducted eight semi-structured interviews with one doctor, three physiotherapists and four RNs between the ages of 30 and 40 in autumn 2019. The topics in the interview guide related to the health professionals’ presentation of information about the CR Programme and their reflections and reasoning related to recruitment.

The interviews lasted about 75 minutes and took place in a suitable room at the hospital. We transcribed the interviews successively.

Analysis

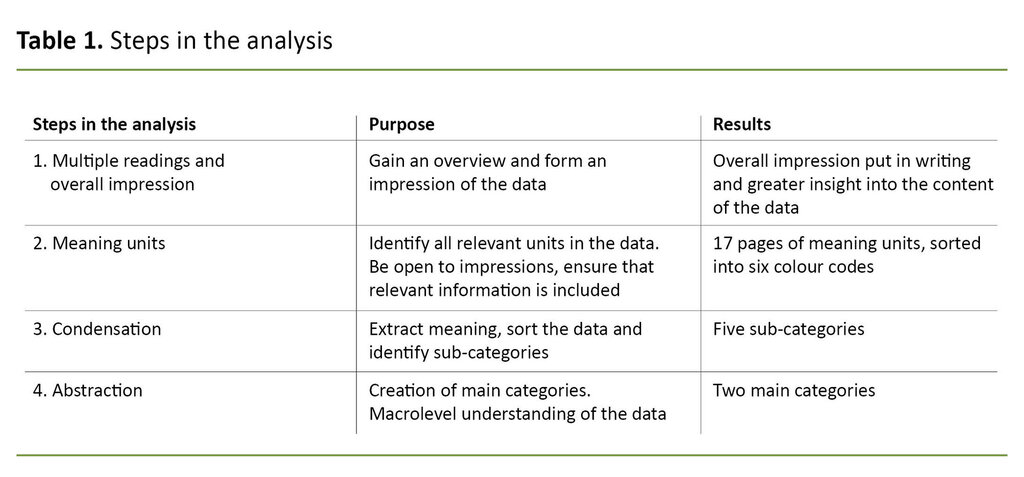

We worked together to conduct a systematic text condensation based on Malterud’s descriptions (21). In the first step of analysis, we read all of the transcribed material several times in order to form an overall impression.

We discussed the general impression, identified meaning units in the text and organised them by theme. Words, sentences or passages were linked to the research question.

We condensed the meaning units into five sub-categories, which we then abstracted into two main categories. We validated the findings by assessing the results in relation to the data and the discussions in the reference group. Table 1 shows the four steps in the analysis process.

Table 2 shows the results of the analysis.

Ethical considerations

The Data Protection Officer for Research and the hospital’s data protection officer approved the project (project number 61140). The informants were given verbal information about the study at an information meeting, and they were sent written information prior to the interviews.

The informants were guaranteed that their identities would be kept anonymous when the paper was published. In addition, they were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time without negative consequences. All of them gave their informed consent.

Resultater

Analysen resulterte i to hovedkategorier med fem underkategorier. Informantene hadde ulike refleksjoner om rekruttering. Resultatet viser at rekrutteringen var preget av tilfeldigheter, mangel på tid og lite definerte systemer.

Rekrutteringen handlet i størst grad om å få satt pasientene på listen over deltakere til Hjerteskolen, som informantene fremstilte som et viktig tilbud.

Randomness rules

An important programme, but insufficient time for recruitment

The informants said that CR was meaningful for the patients because their participation in the programme could help them to change their lifestyle and prevent new disease. One of the informants said, ‘I think all patients can benefit from going and getting the information because it will most likely improve their quality of life after a cardiac event’.

Several said it was difficult to prioritise recruitment when they had so many tasks.

The informants said that the programme was important, but that there was little time for recruitment because they had to prioritise other tasks. One of them said, ‘We have enough to do already, and then we’re supposed to do this too. I’m sure it’s why people just give referrals and don’t bother to get involved’.

Several said it was difficult to prioritise recruitment when they had so many tasks. One of them said, ‘I’m unsure about that. Everyone gets the information, but during hectic periods they probably get inadequate information’. Another said, ‘I don’t have time to ask the patients; I just put them on the list’.

Parameters and limitations

The lack of interpreters and relevant written information were among the parameters that limited recruitment. The informants said that the lack of interpreters presented a challenge. One of them stated, ‘I have to admit that I’ve rarely given information to patients through an interpreter’.

As a solution to the lack of interpreters, the informants explained that they used an employee who spoke Urdu. One of them said, ‘We are able to reach those from Pakistan, thanks to one of our colleagues, but this assumes that he’s at work’. Several informants said that the written information was only available in Norwegian. One said, ‘It’s only in Norwegian, which is a problem’.

Lack of a system

‘Lack of a system’ entailed a lack of guidelines, and recruitment therefore happened randomly. Moreover, there was no clear distribution of responsibility to indicate which professional group was responsible for recruitment.

Regarding the question of who was responsible for recruitment, the informants disagreed among themselves. One said, ‘I don’t know if it’s a task for the nurses or the doctors’.

The informants said that they did not talk with their colleagues about how they recruited patients. When asked how the staff communicated with each other about the CR Programme, one informant said, ‘We don’t’.

The main concern is to get the patients on the list

Strategy

The informants said that they used various strategies when recruiting patients, such as adapting their communication, making positive comments about the programme and asking a doctor to speak with the patients about it. One said, ‘I try to sell it as much as I can and get them to say yes. Quite simply, I try to convince them’.

The informants said that the strategies they used produced varying results. One of them said that the department had put increased focus on the importance of sitting down with the patients: ‘You become more aware of how important it is to sit down at their bedside and chat with them’.

Assessments

The informants made different assessments regarding recruitment, but a common one was that all patients should be put on the list. The informants gave consideration to when it was best to recruit patients and how receptive the patients would be.

One of them said, ‘I observe the situation and see how the patient responds. If they are not very interested, we just give them the heart information, and say nothing about the CR Programme’. Another one explained, ‘Some of us inform the patients right before they go in for an angiogram, when many of the patients are naturally quite nervous’.

Discussion

Below we discuss the results of the study in relation to relevant research. The results show that recruitment was characterised by randomness, insufficient time and poorly defined systems. Recruitment mainly entailed putting patients on a participant list for the CR Programme, which the informants described as an important measure.

Randomness rules

The results suggest that the informants thought that the CR Programme was important, but that challenges related to time, systematic referrals, written information and a lack of interpreters affected recruitment to the programme.

The manner in which patients are recruited is believed to be significant for whether they choose to participate. According to Beatty et al. (20), CR is an under-utilised service because few patients are recruited.

In this context, recruitment consists of a conversation between the health professional and the patient with the goal of encouraging the patient to participate. In our study, the informants stated that they recruited patients by talking with them.

However, low enrolment numbers suggest that conversations are not enough (20). According to Beatty et al. (22), systematic referrals can help to increase participation and enable health professionals to recruit patients as part of a busy workday (20).

Our informants told us that speakers of a foreign language were recruited only occasionally.

If recruitment to the CR Programme is part of systematic efforts within the department, time for recruitment will probably be given priority. Systematic referrals can also help to achieve the goal of equal access to the programme (4).

Our informants told us that speakers of a foreign language were recruited only occasionally, and thus access to this health programme is not equal. On the other hand, Grace et al. (10) found that systematic referrals did not result in higher participation, but that the strategy promoted equal access.

However, it is reasonable to assume that systematic referrals alone are not enough to ensure better utilisation of the programme. It may be necessary, for example, to translate the written information into several different languages and to increase access to interpreters to promote equal access.

According to the Norwegian Patients’ and Users’ Rights Act (8), patients have a right to the information they need to take care of their own health and to protect their rights. This information must be adapted to the patient’s individual circumstances (8).

By using systematic referrals, all patients will be referred automatically, but this does not necessarily ensure that the individual adaptation requirement will be met.

Systematic referrals can deprive patients of the chance to be actively involved in their own health care. When this occurs, the patient becomes a recipient, not a participant, which is not in keeping with the concept of empowerment (6).

Recruitment lacks guidelines

Gravely-Witte et al. (23) found that they achieved the highest enrolment by using a combination of systematic referrals and patient conversations. This combination can promote better utilisation of the programme as well as equal access to it.

The combination of systematic referrals and information adapted to the patient’s individual circumstances can create a framework in which patients can make their own decisions.

The results indicate that recruitment to the CR Programme lacks structure in the form of guidelines that could potentially ensure the patient’s right to equal access to health services.

According to the Specialist Health Services Act (24), regional health authorities are responsible for ensuring that the entire population in the health region is offered equivalent specialist health services.

Equivalent services means that everyone has equal access to health and care services, regardless of diagnosis, place of residence, financial situation, gender, ethnicity and life situation.

The results also suggest that there is no system to determine which professional group is responsible for recruitment at the hospital.

To achieve equivalent services, the regional health authorities must organise the services based on the patient’s circumstances and needs (25). This work will be demanding, but studies have shown that participation in CR reduces morbidity, improves quality of life and has socioeconomic benefits, as more people are able to return to the labour force (11–16).

The results also suggest that there is no system to determine which professional group is responsible for recruitment at the hospital. As a result, nobody takes responsibility since the employees do not feel a sense of ownership for recruitment.

To help employees feel a sense of ownership, which can impact on their thinking, practice and actions, it can be important to involve them in the process of drawing up recruitment guidelines (26).

The programme is delivered on a day-patient basis, indicating that the patient’s general practitioner could also help with recruitment. In this case, cooperation between general practitioners and hospitals would be needed.

The main concern is to get the patients on the list

The results suggest that the strategies used by the informants did not correspond with the concept of empowerment, but incorporated a more paternalistic view. The results seem to show that the informants did not focus on the patient’s needs, but on their own understanding of what is best for the patient.

The informants employed strategies that involved using a ‘louder voice, ‘convincing the patients’ and ‘fetching the doctor’. Such strategies may have diminished the patients’ motivation to participate in the CR Programme.

A paradigm shift has occurred within the health sector – from a paternalistic view in which the medical experts know what is best for the patient and act according to their own understanding to a view more aligned with empowerment in which the patients are the experts in their own health and have influence over their own treatment (6).

It is understandable that in a busy workday, the informants use strategies to get the patients on the list because they feel the programme is important.

Such a change can be a more appropriate recruitment strategy for increasing enrolment. It is understandable that in a busy workday, the informants use strategies to get the patients on the list because they feel the programme is important. On the other hand, the strategies they use may have a negative impact on recruitment because it may not be the patients themselves who choose to participate.

Rouleau et al. (27) found that patients did not take part in CR due to concerns about their own ability to engage in and travel to the programme. According to Rouleau et al., a short conversation between the health professional and the patient about the obstacles both increases the patient’s intention to enrol and their actual participation.

Health education entails making appropriate assessments and choices that facilitate learning about and mastery of health challenges (6). Health education is an important competency among health professionals in connection with recruitment.

The informants view themselves as experts

The results suggest that the informants think of themselves as experts, meaning they know what is best for the patients. This perception can affect their assessments, and thus recruitment. For example, several of them said that they put the patients on the list without their consent because they believed it was important for the patients to participate.

They may have made this assessment more or less unconsciously, but it is important to be aware of what is done and why it is done by reflecting on one’s own practice and own competence (6).

Evidence-based practice is a goal within the health service. Evidence-based practice means that medical decisions are based on systematically collected, research-based knowledge and user knowledge (29).

Acquisition of competence in connection with recruitment will enable an evidence-based practice grounded in research-based knowledge and user knowledge. This could possibly contribute to an appropriate use of strategies and well-considered assessments related to recruitment.

It is uncertain whether the health education content in university health science studies meets the need for recruitment-related competence (30).

The fact that the informants offered so few reflections could possibly be explained by a lack of health education competence, but it could also have to do with how the interviews were conducted.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

To answer the research question, it was necessary to interview the informants at the hospital. Out of loyalty to their workplace, the informants may have expressed themselves more positively and put less emphasis on any negative experiences. Observations in addition to interviews might have produced more accurate results.

Regarding recruitment of informants, the lead author and the head of the cardiac ward at the hospital worked together on this task. Their collaboration was necessary in order to recruit informants, but it may have affected who was recruited.

The informants were well-spoken, and this could be the reason they were chosen. The data are not necessarily representative of everyone who recruits patients to the CR Programme.

The low number of follow-up questions in the interviews may have prevented the informants’ reflections from coming clearly enough to the fore, for example, when the informants contradict themselves by saying that they believe the programme is important, but the recruitment has an aspect of randomness.

The fact that both researchers analysed the data strengthened the study’s credibility, but this credibility could have been enhanced even further if the informants had validated the results. To achieve reliability, we have tried to be transparent (show what was done) in our explanation of the research process.

While the lack of national guidelines for CR programmes makes it challenging to transfer the results beyond the local context, the results could be relevant for other hospitals that offer CR (21). Therefore, the study could have been strengthened if the data collection had been done at multiple hospitals.

Conclusion

The study identified challenges related to recruitment to one hospital’s CR Programme. The results indicate that ‘randomness rules’ and that ‘the main concern is to get the patients on the list’.

To prevent randomness in recruitment, it may be necessary to develop a system and guidelines for recruitment. Communication among health professionals about how recruitment should be carried out could be beneficial.

To further develop the CR Programme and to avoid the attitude that ‘the main concern is to get the patients on the list’, it may be useful for health professionals who recruit patients to CR to acquire health education competence through training or practice.

References

1. Folkehelseinstituttet. Hjerte- og karsykdommer i Norge. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/hin/helse-og-sykdom/hjerte--og-karsykdommer-i-norge---f/#dagens-situasjon-for-hjerte-og-karsykdommer-i-norge (downloaded 01.05.2019).

2. Meld. St. 19 (2018–2019). Folkehelsemeldinga – Gode liv i eit trygt samfunn. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2019. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/84138eb559e94660bb84158f2e62a77d/nn-no/pdfs/stm201820190019000dddpdfs.pdf (downloaded 10.05.2019).

3. Vestre Viken. Hjerterehabilitering, Ringerike sykehus. Available at: https://vestreviken.no/behandlinger/hjerterehabilitering-ringerike-sykehus (downloaded 19.12.2020).

4. Bratli S. Lærings- og mestringstilbud Oslo. Available at: https://mestring.no/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/generell-brosjyre-141216-web.pdf (downloaded 16.05.2019).

5. Verdens helseorganisasjon (WHO). Rehabilitation after cardiovascular diseases, with special emphasis on developing countries. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva: 1993. World Health Organization technical report series. 0512-3054. 831. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/38455/WHO_TRS_831.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (downloaded 01.05.2019).

6. Tveiten S. Helsepedagogikk: pasient- og pårørendeopplæring. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2020.

7. Stenberg U, Øverby MH, Fredriksen K, Kvisvik T, Westermann KF, Vågan A, et al. Utbytte av lærings- og mestringstilbud. Sykepleien. 2017;(4):52–5.

8. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 63 om pasient- og brukerrettigheter (pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63 (downloaded 23.04.2020).

9. St. Olavs hospital. Automatisk henvisning får flere på hjerterehab. Available at: https://stolav.no/fag-og-forskning/kompetansetjenester-og-sentre/nasjonal-kompetansetjeneste-trening-som-medisin/hjerteinfarkt-og-angina-pectoris/automatisk-henvisning-far-flere-pa-hjerterehab (downloaded 29.08.2020).

10. Grace SL, Leung YW, Reid R, Wu G, Alter DA. The role of systematic inpatient cardiac rehabilitation referral in increasing equitable access and utilization. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention. 2012 Jan.–Feb.;32(1):41–7.

11. van Engen-Verheul M, de Vries H, Kemps H, Kraaijenhagen R, de Keizer N, Peek N. Cardiac rehabilitation uptake and its determinants in the Netherlands. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2013 Apr.;20(2):349–56. DOI: 10.1177/2047487312439497

12. Ruano-Ravina A, Pena-Gil C, Abu-Assi E, Raposeiras S, van 't Hof A, Meindersma E, et al. Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016 Nov.;223:436–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.120

13. Astley MC, Neubeck NL, Gallagher AR, Berry AN, Du AH, Hill AM, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation: unraveling the complexity of referral and current models of delivery. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2017 May–Jun.;32(3):236–43.

14. Munkhaugen J, Sverre E, Peersen K, Egge Ø, Eikeseth CG, Gjertsen E, et al. Patient characteristics and risk factors of participants and non-participants in the NOR-COR study. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal. 2016 Nov.;50(5–6):317. DOI: 10.1080/14017431.2016.1202445

15. Peersen K, Munkhaugen J, Gullestad L, Liodden T, Moum T, Dammen T, et al. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in secondary prevention after coronary events. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2017 Sep.;24(13):1360–8. DOI: 10.1177/2047487317719355

16. Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation post–myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Heart Journal. 2011 Oct.;162(4):571–84. DOI: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.017

17. LHL. Hjerterehabilitering i Helse Sør-Øst. Available at: https://www.lhl.no/globalassets/ressurssenter-for-hjerterehabilitering/dokumenter/kartleggingsrapport_inkl_vedlegg.pdf (downloaded 06.05.2020).

18. Olsen SJ, Schirmer H, Bønaa KH, Hanssen TA. Cardiac rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary intervention: Results from a nationwide survey. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2018 Mar.;17(3):273–9. DOI: 10.1177/1474515117737766

19. Bossy D, Knutsen IR, Rogers A, Foss C. Group affiliation in self‐management: support or threat to identity? Health Expectations. 2017;20(1):159–70. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12448

20. Beatty AL, Li S, Thomas L, Amsterdam EA, Alexander KP, Whooley MA. Trends in referral to cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: data from the national cardiovascular data registry 2007 to 2012. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;63:2582–3. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.030

21. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

22. Lorensen M, Hounsgaard L, Østergaard-Nielsen G. Forskning i klinisk sygepleje –metoder og vidensudvikling. København: Akademisk forlag; 2003.

23. Gravely-Witte S, W. Leung Y, Nariani R, Tamim H, Oh P, Chan MV, et al. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on referral and enrollment rates. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2009 Dec.;7(2):87. DOI: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.223

24. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 61 om spesialisthelsetjenesten m.m. (spesialisthelsetjenesteloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-61 (downloaded 24.03.2020).

25. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Likeverdige helse- og omsorgstjenester – God helse for alle. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/2de7e9efa8d341cfb8787a71eb15e2db/likeverdige_tjenester.pdf (downloaded 06.05.2019).

26. Jensen BB. Handlekompetance, sundhedsbegreber og sundhedsviden. In: Hounsgaard L, Eriksen J, eds. Læring i sundhedsvæsenet: Munksgaard; 2000. s. 191–211.

27. Rouleau CR, King-Shier KM, Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Aggarwal SG, Arena R, Campbell TS. A qualitative study exploring factors that influence enrollment in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018 Feb.;40(4):469–78. DOI: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1261417

28. Rouleau CR, King-Shier KM, Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Bacon SL, Aggarwal S, Arena R, et al. The evaluation of a brief motivational intervention to promote intention to participate in cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling. 2018 Nov.;101(11):1914–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.015

29. Jamtvedt G, Nortvedt MW. Kunnskapsbasert ergoterapi – et bidrag til bedre praksis! Ergoterapeuten. 2008(1):10–8.

30. Vågan A, Raaen FD, Ødegaard NB, Rajka L-GK, Tveiten S. Helsepedagogikk i læreplaner – en didaktisk analyse. Uniped. 2019;42(04):368–80. DOI: 10.18261/issn.1893-8981-2019-04-04

Comments