In the child’s best interest? Making the decision to end life-sustaining treatment

Healthcare personnel found it challenging to judge what was in the child’s best interest. The child’s right to autonomy and involvement was often not heeded, and the child was rarely included in the decision-making process.

Background: Paediatric nurses and paediatricians face difficult decisions when treating children with life-threatening and life-limiting diseases. Making decisions about whether to provide or withdraw life-sustaining treatment from seriously ill children involves challenges on a human and medical level, for the healthcare personnel as well as for the families.

Objective: The study aimed to examine the decision-making experiences of paediatric nurses and paediatricians when deliberating whether to end life-sustaining treatment.

Method: Our chosen method involved the use of a qualitative design and a focus group interview. The analysis was conducted after systematic text condensation. Eight paediatric nurses and paediatricians with clinical experience from paediatric wards took part in the study.

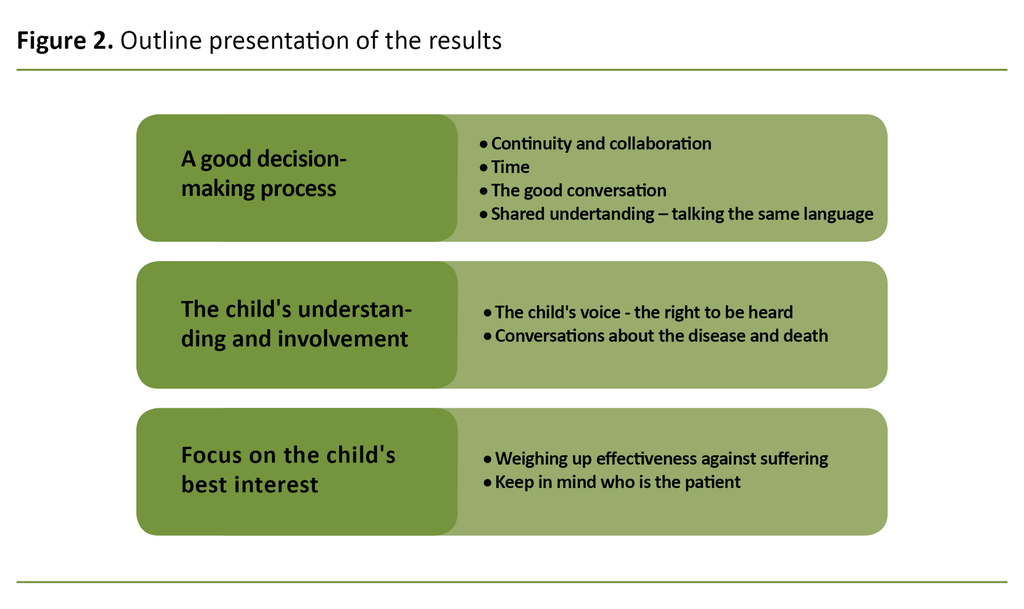

Results: The findings show that end-of-life decision-making is extremely challenging for healthcare personnel. The main findings were categorised in three coded groups: 1) Good decision-making processes, 2) The child’s understanding and decision-making involvement, and 3) Focus on the best interests of the child.

Conclusion: Ensuring continuity and setting up patient care teams were highlighted as important ways of securing a good decision-making process. Good communication and liaison between families and healthcare personnel were important factors in bringing about good decision-making processes that put the child’s best interest first. The findings show that the child’s right to autonomy and decision-making involvement is often not heeded, and that children are only engaged in the decision-making to a very limited extent. Due to medical developments, healthcare personnel found it increasingly challenging to judge what is in the child’s best interest. The child is the patient. It is therefore essential that all decisions about the child’s treatment are made in the best interest of the child.

The treatment of children with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions aims to preserve life. To find the right balance between the treatment’s effectiveness and its adverse effect on on the patient, it is necessary to consider whether it is safe and advisable on ethical, medical and legal grounds for the child’s treatment to continue (1).

Research (2–4) and clinical experience from paediatric wards suggest that advance care planning and end-of-life decision-making are challenging, sensitive and upsetting themes for healthcare personnel as well as the children’s families.

The risk and benefit of any treatment must be considered, and the choice of intervention must always be based on the child’s best interest. The medical decision-making process works best when all members of the patient care team collaborate and when the team includes nurses, doctors, parents and the child (3, 5).

A dearth of good guidelines and research

Healthcare personnel face several ethical challenges when they need to initiate conversations about end-of-life decision-making in respect of seriously ill children. Part of the challenge relates to uncertainty about when and how these conversations are best started, insufficient familiarity with current legislation that protects the rights of children, as well as fears of taking away the family’s hope or ruining a trusting relationship (6).

There is a demand for better access to good guidelines to help alleviate the situation for the children and their families, and to ensure that everyone involved with the patient’s medical treatment takes part in the decision-making process. Insufficient relevant research has been conducted on this topic (6).

Early discussion about treatment choices is desirable, but there is a dearth of good guidelines that can aid the decision-making process and help reach a consensus among those involved with the medical treatment and nursing care for seriously ill children (6, 7).

We found few studies that describe the end of life care decision-making experiences of both doctors and registered nurses. None of the studies we identified describe Norwegian settings, and very few of them describe the experiences of paediatric nurses.

In order to improve the quality of the decision-making process with respect to ending life-sustaining treatment, and in order to ensure that decisions are made in the child’s best interest, it was important to examine the experiences of both paediatric nurses and paediatricians.

Research questions

We formulated the following research questions:

- In the experience of paediatric nurses and paediatricians, what factors are essential to securing a good end-of-life decision-making process?

- What safeguards are in place to uphold the principle of making decisions in the child’s best interest?

Method

The study had a qualitative descriptive design (8). We conducted a focus group interview with eight informants from different paediatric wards in order to examine hospital decision-making processes that involved collaboration between paediatric nurses and paediatricians.

When dealing with sensitive and taboo topics that involve several individuals, focus group interviews can be helpful in encouraging informants to express their own opinions and experiences (8).

Sample

We used a strategic sample. We contacted paediatric nurses and paediatricians from five different paediatric wards in a hospital run by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. In order to gather experiences that would provide a good strength of information we required all informants to have been working for at least two years on a paediatric ward.

The informants were also required to have experience of difficult end-of-life decision-making processes associated with the life-sustaining treatment of children (8, 9) (see Fact Box).

The various ward managers suggested potential candidates. Those who met the inclusion criteria were contacted by e-mail with information about the study and a consent form.

A total of 16 individuals were invited. Four paediatric nurses and four paediatricians from three wards were included, the majority of them women. All had many years of clinical experience from their respective wards.

Data collection

We conducted the focus group interview at hospital premises over two hours in December 2018. Three of the authors took part in the interview. One acted as moderator and led the interview, one was responsible for ensuring that the opinions of all informants were heard, and the third author made a note of the main points that cropped up during the conversation (8,10).

The interview was recorded on audiotape, which was deleted on completion of the analysis. The interview was transcribed independently by each of the three authors who took part in the interview. The transcript word count was 17 053.

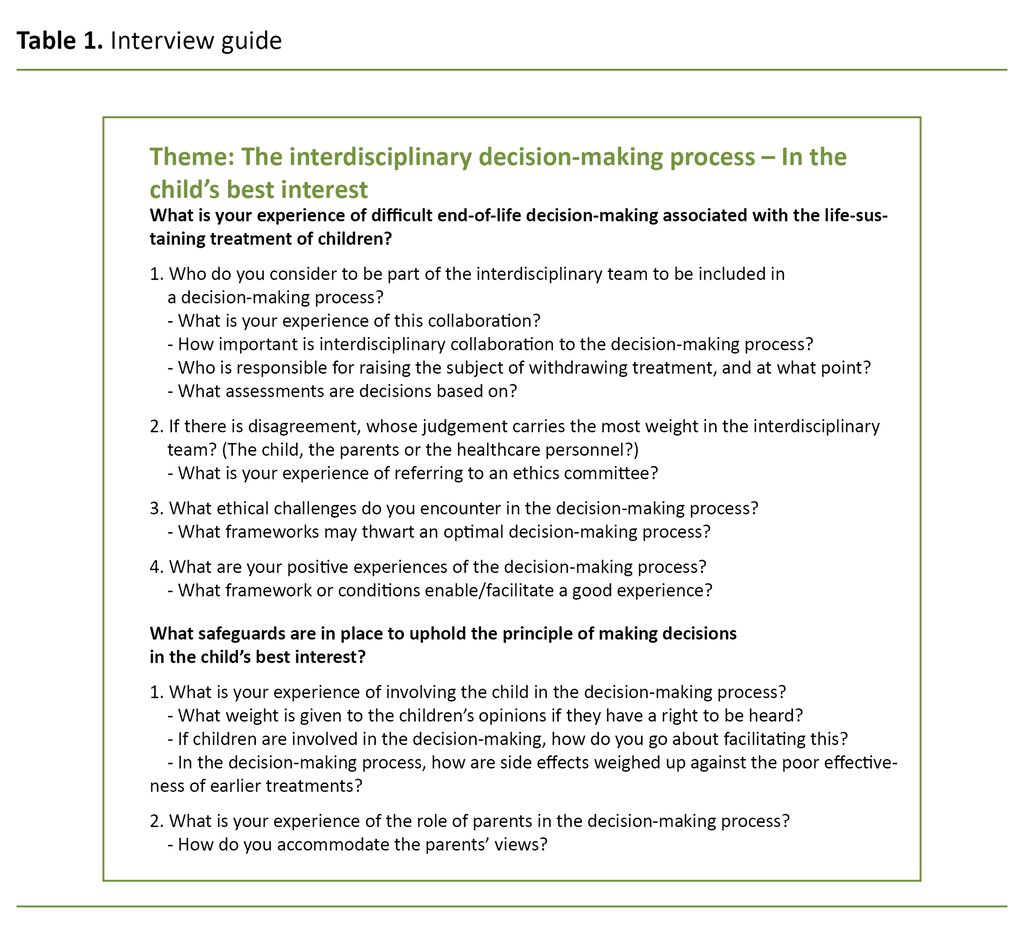

The focus group interview was based on a semi-structured interview guide (Table 1). The main themes were based on earlier research and clinical experience. The sub-questions were intended to help informants elaborate on their answers, but as it turned out, there was little need for them because the informants excelled at going into detail (8).

We conducted a pilot interview (10) to test the content and sequence of our questions. On this basis, we excluded some of our questions.

Analysis

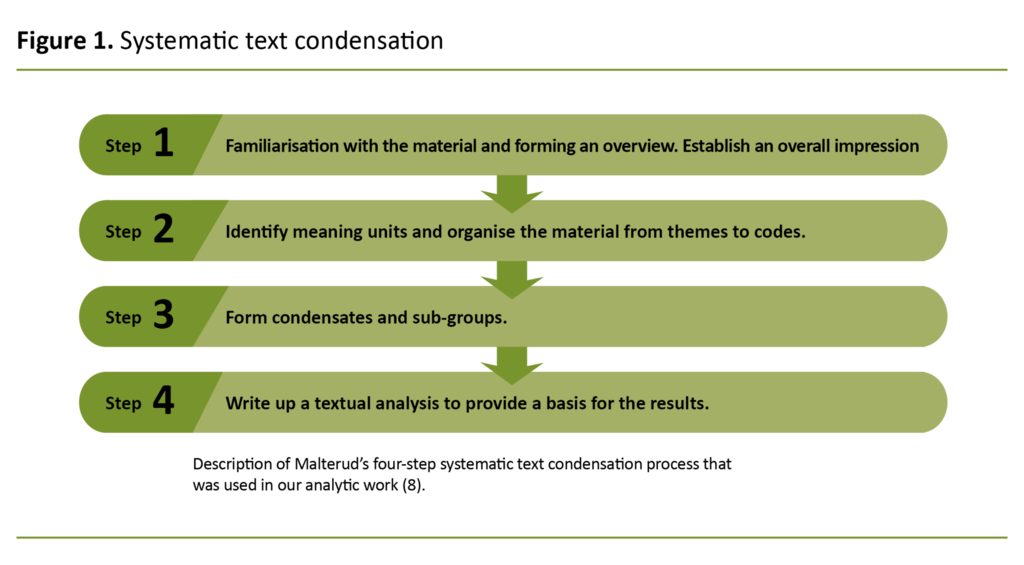

The data material was analysed using a four-step systematic text condensation procedure (8) (Figure 1). In step one, we established an overall impression by re-reading the text numerous times. We also formulated a set of preliminary themes. In the next step, we transformed meaning units into codes by means of colour coding. We identified themes that covered the same issue.

In step three, we extrapolated the essence of the data that had been coded in step two. We condensed the various meaning units and formed sub-groups for each code. In the last step, we drafted a textual analysis that formed the basis for our results. Table 2 shows extracts from the analytic process.

Ethical considerations and methodology issues

The study was approved by the Data Protection Officer at the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference code 780166, and by the data protection department at the hospital concerned. All informants signed an informed consent form.

Results

Our analysis produced three main groups (Figure 2): The good decision-making process, The child’s understanding and decision-making involvement, and Focus on the child’s best interest.

The good decision-making process

Setting up a patient care team was highlighted by several informants as an important factor to ensure a good decision-making process. One of them emphasised that collaboration and good communication between doctors and nurses can counteract the formation of opposing views across the disciplines.

One paediatrician reported that the nurses take a more holistic view of the patient because they are closer to the families and can see the bigger picture.:

‘Sometimes I feel that perhaps the nurses take a more holistic view of the patient. While the doctors tend to focus more on the diagnosis, not all doctors and not all nurses, but it’s a bit as if this particular disease is something I want us to be able to cure. Not the whole patient, but the disease’ (L2).

Pressures of time were highlighted by several informants as a factor that thwarted good decision-making processes. The informants felt that discussions within the patient care team were challenging if they were pressed for time:

‘I think we need to get better at taking those five minutes to talk to one another, rather than everybody just saying they haven’t got the time’ (S1).

The informants remarked that medicine has become a more technical profession, with high efficiency demands. One paediatric nurse mentioned that scant opportunities for good conversations may well be one of the consequences.

There was consensus that all decisions must be made by an interdisciplinary healthcare team whose liaison with the family is essential to ensure that everyone agrees with the decision. There was no consensus about whether anyone who is not a member of the interdisciplinary team should be able to initiate conversations about the patient’s condition.

A shared understanding of the situation was required to make a choice about levels of continued treatment, and the parents’ views were important in the decision to end life-sustaining treatment. Several informants felt it was a major ethical dilemma when there was disagreement or a difference of perceptions with regard to the child’s situation.

The child’s understanding and decision-making involvement

The informants wanted the children to be involved at an earlier stage of the decision-making process if possible, to increase their understanding of their own situation and ensure their engagement.

Keeping the child informed was considered important but it was not always achieved. It was difficult to inform the child without the parents’ consent, even when they knew that the child was entitled to information and involvement:

‘It is the parents who are the children’s advocates, their support network and closest allies. So if they are not on side, it feels very difficult to talk directly to the children. You can’t just go trampling all over it’ (L1).

Keeping the child informed was considered important but it was not always achieved.

Several informants believed that children often understand more than what the healthcare personnel and the parents think they do, but that the children do not take the initiative to talk about their condition and death unless the healthcare personnel invite them to do so. Talking about the seriousness of a disease is key to ensuring that the child can be involved in the decision-making process, subject to their age and maturity:

‘I think the kids feel it in their bones. They recognise the symptoms, they feel that their bodies don’t work anymore. So I think that the parents, and us as well, we are too worried about starting these conversations. They understand that we understand, they understand that their parents understand, and that no-one is talking about it’ (S2).

Focus on the child’s best interest

The informants felt it was difficult to know when life-sustaining treatment should be withdrawn. Although the child’s best interest must guide the decision-making, this principle was not always heeded.

The informants repeatedly mentioned the difficulty of determining what is a tolerable level of adverse effects in the course of a treatment. According to one of the doctors, the general public considers death to be the enemy and society believes that you have given up if life-sustaining treatment is withdrawn.

One paediatric nurse had found that years of clinical experience made it more difficult to decide whether to end the treatment, because in some cases the child had survived even if no cure would have been available in the past. While treatments have improved, several informants raised the point that more attention is now being paid to the child’s quality of life.

Several pointed to the importance of keeping in mind who the patient is. According to one doctor, parents often have strong wishes about the treatment of their child, but they are not the patient.

The informants emphasised that it is essential for them to listen to the parents in order to consider what constitutes a good quality of life for the child. However, the objective must always be to act in the best interest of the child.

Discussion

The good decision-making process

In order to reach a shared understanding, collaboration and good communication within the patient care team was important. Any disagreement about withdrawal of treatment made the decision-making harder. According to one doctor, disagreement within the group of health professionals could be due to the fact that nurses often acquire a more holistic picture of the patient while some doctors take a more diagnostic approach.

A decision in the best interest of the child is best arrived at by focusing on the child who is ill rather than being concerned with the diagnosis (11). Professional disagreement may also be due to the fact that nurses and doctors fulfil different roles. The doctor carries the legal responsibility (5), whereas the role of paediatric nurse entails a closer connection to the suffering experienced by the child and the family. (12).

The findings suggest that pressures of time and a lack of initiative make it difficult to reach a consensus.

However, one informant had found that there were no professional disagreements between nurses and doctors if they took the time to talk to one another within the patient care team. Several informants mentioned that cross-disciplinary discussions were rarely initiated, not even by the people who considered this to be their area of responsibility. The findings suggest that pressures of time and a lack of initiative make it difficult to reach a consensus.

When the informants discussed the collaboration between healthcare personnel and parents, the setting up of a patient care team, continuity and good communication were listed as important factors for achieving a good decision-making process. The informants had found that it was difficult to ensure continuity because they also needed to attend to other tasks.

These findings are supported by earlier research (13, 14) which showed that in the opinion of parents, too many nurses and doctors were involved with caring for their child, and that establishing a relationship of trust at an early point, and continuity, are important factors that contribute to good decision-making processes.

The informants explained that talking with children and parents was important to establish a shared understanding. Good communication can prevent disagreement between healthcare personnel and parents and can help parents feel that they are seen, heard and listened to. Sitting down together without being disturbed is more conducive to a good conversation.

We found that good communication and individual adaptation are thwarted by procedures and pressures of time. This matches the findings of earlier research (13, 14). Inadequate communication between families and healthcare personnel can disrupt the families’ ability to make decisions about the child’s continued treatment, and will impact on the decision-making process (15).

The informants found it difficult to decide to withdraw life-sustaining treatment unless this was accepted by the parents and, if possible, the child. Healthcare personnel make the decision to withdraw or continue treatment without involving the parents in order to protect them (16).

The informants attached great importance to the parents’ views.

Our findings gave no indication of a failure to engage with parents and generally showed that the informants attached great importance to the parents’ views. Disagreements can arise about who has the authority to make the final decision (15), although it is the doctor in charge who carries the legal and medical responsibility (2, 5).

Parents engage better with the decision-making process if they are allowed time to reflect on the child’s best interest (14, 17). As a part of the work to establish a shared understanding, healthcare personnel have a statutory duty to keep patients and their families informed and to ensure that the information they provide has been understood (18, 19).

In our study, the informants identified a medical and ethical challenge relating to a lack of consensus about who is responsible for talking to the families about withdrawing life-sustaining treatment. This disagreement means that it takes longer before healthcare personnel talk to the family, which may prolong the child’s suffering.

The findings highlight how important it is that healthcare personnel start conversations. The parents felt it was pivotal to the decision-making process that healthcare personnel were open about sensitive and upsetting matters (13, 14).

The child’s understanding and decision-making involvement

Where age and maturity allow, children should be heard and must be involved in any decision made about themselves. As far as possible, decisions about care should involve the child through informed consent (20).

Inclusion may give the child better insight and understanding of their own disease and treatment pathway (1, 21). Several informants had experienced that no heed had been taken of the child’s right to autonomy and decision-making involvement, and that the children were rarely included, informed and listened to.

Several informants had experienced that no heed had been taken of the child’s right to autonomy and decision-making involvement.

The informants felt it was difficult to include the child without the parents’ consent. While parents cannot deny the child information, they can influence the way in which such information is conveyed. There is no lower age limit imposed on the child’s right to be heard, but the information given must be adapted to the age and maturity of the child (18).

This problem represents an ethical dilemma for healthcare personnel. On the one hand, the child has a right to receive information from healthcare personnel (19), but on the other hand healthcare personnel are worried about losing the parents’ trust. The informants pointed to the importance of including the parents, who constitute the child’s support network and are their closest allies, but found it ethically challenging when parents did not wish their child to be informed.

Several informants explained that worries about losing the parents’ trust were prioritised over the rights and needs of the child. The findings of our study suggest that healthcare personnel attach more importance to the parents’ opinions than to the legislation. Whether or not the child receives information depends on whatever the parents consider to be in the child’s best interest.

Focus on the child’s best interest

The balance between the beneficial and adverse effects of treatment must be considered from an ethical, medical and legal perspective (1). Research (14) shows that children receive excessive treatment, and that the ethical issues are challenging for healthcare personnel. This concurs with the findings of our own study.

Several informants had found that quality of life is now more frequently talked about. The child’s best interest is the guiding principle for all paediatric health care (1, 22), but healthcare personnel and family members may have different views about what constitutes their best interest. The child must not be harmed by the treatment, and any decisions made must be judged to be in the child’s best interest (5, 23).

The informants made it clear that the patient was the child, not the parents. Experience from clinical practice and the findings of our study show that the decision-making process engages with the parents more often than the child. In the opinion of the informants, both the child and the parents should be listened to, but the child’s best interest must take priority.

The parents’ natural wish for their child to survive can overshadow the potential suffering that the treatment may inflict on the child. One informant questioned what is a good quality of life for the child, and whether the parents would have chosen this life for themselves.

Clinical experience as well as medical and research literature (5, 24, 25) tell us that parents will sometimes try to demand that healthcare personnel continue to provide life-sustaining treatment. According to the legislation, healthcare personnel can only provide treatment that is considered to be medically and ethically safe (19, 26).

Methodology

There is no rule to say how many focus groups are required for a study to be valid. In optimal circumstances, a single group interview can produce rich material with a satisfactory strength of information (8).

There were good focus group dynamics and the discussions flowed easily, as pointed out by the informants after the event. Considering the scope of the study, we therefore found it warranted to conduct only a single focus group interview, although a greater number of interviews could have produced richer data.

To assess the strength of information, it is important to consider whether the data were challenged as the conversation progressed (8). In our judgement, there was good group interaction and discussion, which produced rich data material and shed light on our themes from different points of view.

We have personal experience of end-of-life decision-making processes. Being close to the field of practice can impact on the validity of the study. We were able to understand the informants’ professional jargon and relate to their experiences, which may have contributed to better flow in the interview.

However, personal experiences and reflections may have influenced our analysis and interpretation of the results (10). We felt that we managed to uphold our researcher role by not allowing our own experiences to influence the process.

Our background as paediatric nurses had led us to believe that there would be significant discrepancies between the aspects of the process that were considered most important by doctors and nurses respectively. We had assumed that our results and discussions would reveal greater differences between the professions than what was in fact the case. It was therefore interesting to see that the informants attached importance to many of the same factors and that they had a good insight into their own and the other profession’s roles and functions.

On reflection, the gender perspective was considered not to have influenced the final result. Because the study aimed to build on experiences, gender was not key to the strategic sample. A homogenous group may produce less nuanced knowledge, but the study’s strength of information is based on the informants’ experience and competence (8).

The study’s analytic methodology of systematic text condensation takes the phenomenological view that subjective experiences constitute valid knowledge, and that the analysis describes relevant aspects of a phenomenon as accurately as possible (8).

Conclusion

According to our findings, the informants find it difficult to make practical use of their own knowledge and wishes about optimal end-of-life decision-making in the best interest of the child. There is a risk that the child’s voice is not heard and that the child is therefore not sufficiently included in the decision-making process. In order to safeguard the principle that all decisions must be made in the child’s best interest, it is necessary to remember who is the patient.

There is a need to enhance our knowledge about end of life care decision-making from the child’s point of view, and about the consequences for children if they are not included.

The study puts a topical and important ethical issue on the agenda. We believe that the results will be useful to the day-to-day work of healthcare personnel who care for seriously ill children.

References

1. Weise KL, Okun AL, Carter BS, Christian CW. Guidance on forgoing life-sustaining medical treatment. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):1–9.

2. Hauer J. Pediatric palliative care. UpToDate. 2017. Available at:https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pediatric-palliative-care (downloaded 17.01.2018).

3. Smith A. Communication of prognosis in palliative care. UpToDate. 2017. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/communication-of-prognosis-in-palliative-care?source=see_link (downloaded 17.01.2018).

4. Dupont-Thibodeau A, Hindié J, Bourque CJ, Janvier A. Provider perspectives regarding resuscitation decisions for neonates and other vulnerable patients. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2017;188(3):142–7.

5. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for palliasjon til barn og unge uavhengig av diagnose. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2017. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/palliasjon-til-barn-og-unge/seksjon?Tittel=grunnleggende-barnepalliasjon-etikk-og-5715#uenighet-om-beslutninger-om-behandling-av-barnet-dr%C3%B8ftes-i-%C3%A5pen-dialog (downloaded 23.01.2018).

6. Hein K, Knochel K, Zaimovic V, Reinmann D, Monz A, Heitkamp et al.Identifying key elements for paediatric advance care planning with parents, healthcare providers and stakeholders: a qualitative study. Palliative Medicine. 2020;34(3):300–8. DOI: 10.1177/0269216319900317

7. Sasazuki M, Yasunari S, Kira R, Toda N, Ichimiya Y, Akamine S et al. Decision-making dilemmas of paediatricians: a qualitative study in Japan. BMJ Open.2019;9(8):e026579. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026579

8. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning: En innføring. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

9. Johannessen A, Tufte PA, Kristoffersen L. Introduksjon til samfunnsvitenskapelig metode. 5th ed. Oslo: Abstrakt; 2016.

10. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3rd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

11. NOU 2017: 16. På liv og død. Palliasjon til alvorlig syke og døende.Oslo: Departementenes servicesenter, Informasjonsforvaltning; 2017.

12. Barnesykepleieforbundet NSF (BSF). Barnesykepleier – funksjons- og ansvarsområder. Oslo: NSF; 2017.

13. Lotz JD, Daxter M, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Fürer M. «Hope for the best, prepare for the worst»: a qualititive interview study on parents' needs and fears in pediatric advance care planning. Palliative Medicine. 2016;31(8):764–71. DOI: 10.1177/0269216316679913

14. Popejoy E, Pollock K, Almack K, Manning JC, Johnston B. Decision-making and future planning for children with life-limiting conditions: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2017;43(5):627–44. DOI: 10.1111/cch.12461

15. Richards CA, Starks H, O’Connor RM, Bourget E, Hays RM, Doorenbos AZ. Physicians perceptions of shared decision-making in neonatal and pediatric critical care. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine.2018;35(4):669–76. DOI: 10.1177/1049909117734843

16. De Vos MA, Bos AP, Plötz FB, Van Heerde M, De Graaff BM, Tates K et al. Talking with parents about end-of-life decisions for their children. Pediatrics. 2014;135(2):465–76. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-1903

17. Aarthun A, Akerjordet K. Parent participation in decision-making in health-care services for children: an integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012;22(2):177–91. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01457.x

18. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 63 om pasient- og brukerrettigheter (pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63?q=pasient%20og%20brukerrettighetsloven (downloaded 25.01.2018).

19. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 64 om helsepersonell (helsepersonelloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64?q=helsepersonelloven (downloaded 25.01.2018).

20. Lov 17. mai 1814. Kongeriket Noregs grunnlov (grunnlova). Available at:https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1814-05-17-nn?q=kongeriket%20noregs%20grunnlov (downloaded 25.01.2018).

21. Whitty-Rogers J, Alex M, MacDonald C, Gallant DP, Austin W. Working with children in end-of-life decision making. Nursing Ethics.2009;16(6):743–57. DOI: 10.1177/0969733009341910

22. Larcher V, Craig F, Bhogal K, Wilkinson D, Brierley J. Making decisions to limit treatment in life-limiting and life-threatening conditions in children: a framework for practice on behalf of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(2):1–26. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306666

23. Slettebø Å. Sykepleie og etikk. 6th ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2013.

24. Larcher V, Carnevale F. Etikk. In: Goldman A, Hain R, Liben S, eds. Grunnbok i barnepalliasjon. 1st ed. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget; 2016.

25. Fromme EK, Smith MD. Ethical issues in palliative care. UpToDate. 2017. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ethical-issues-in-palliative-care?source=see_link (downloaded 17.01.2018).

26. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 61 om spesialisthelsetjenesten (spesialisthelsetjenesteloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-61?q=spesialisthelsetjenesteloven (downloaded 25.01.2018).

27. McNamara-Goodger K, Feudtner C. Historikk og epidemiologi. In: Goldman A, Hain R, Liben S, eds. Grunnbok i barnepalliasjon. 1st ed. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget; 2016.

Comments