Experiences gained from testing a work placement supervision model at the Master’s degree level

The model helped to ensure that work placement supervisors were better prepared to welcome students, and this strengthened the quality of learning. However, this requires management support, as well as planning and professional resources.

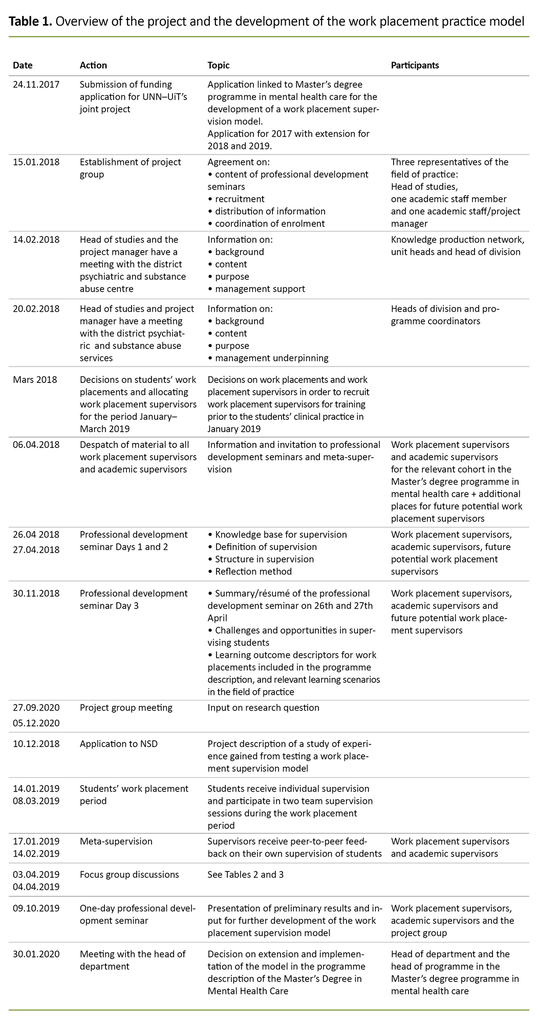

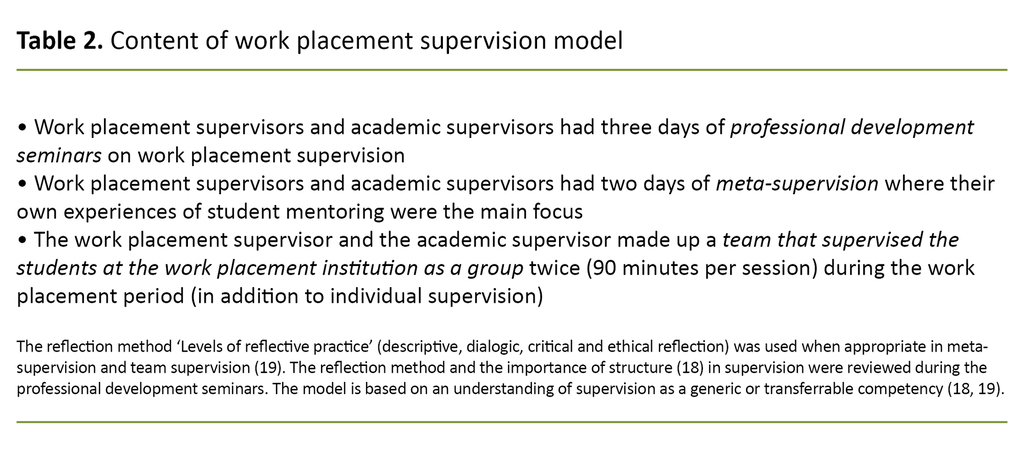

Background: Universities Norway (UHR) and the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (NOKUT) have shown interest in work placements and have issued guidelines to enhance the quality of supervision, supervision competence and collaboration between various actors. Studies show that supervision competence is vital in safeguarding the quality of work placement supervision. In the middle of December 2017, the Master’s Degree programme in mental health studies at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, and the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN), were granted funding for a joint project to develop a model for work placement supervision. The objective was to enhance the quality of student supervision, the competence of work placement supervisors and academic supervisors, and the collaboration between UiT (University of Tromsø) and the field of practice. The project group, which consisted of representatives from the specialist and primary health services as well as UiT, developed and implemented the model, and acted as reference group for the study. After testing the model, we designed the study. The model included professional development seminars, meta-supervision and team supervision of students in groups. The study examined experiences gained from testing the model.

Objective: The objective was to develop knowledge about the experiences gained from testing the practice placement supervision model.

Method: The study had a descriptive and exploratory design. For the collection of data, a qualitative method with focus group discussions was used. The analysis consisted of systematic text condensation.

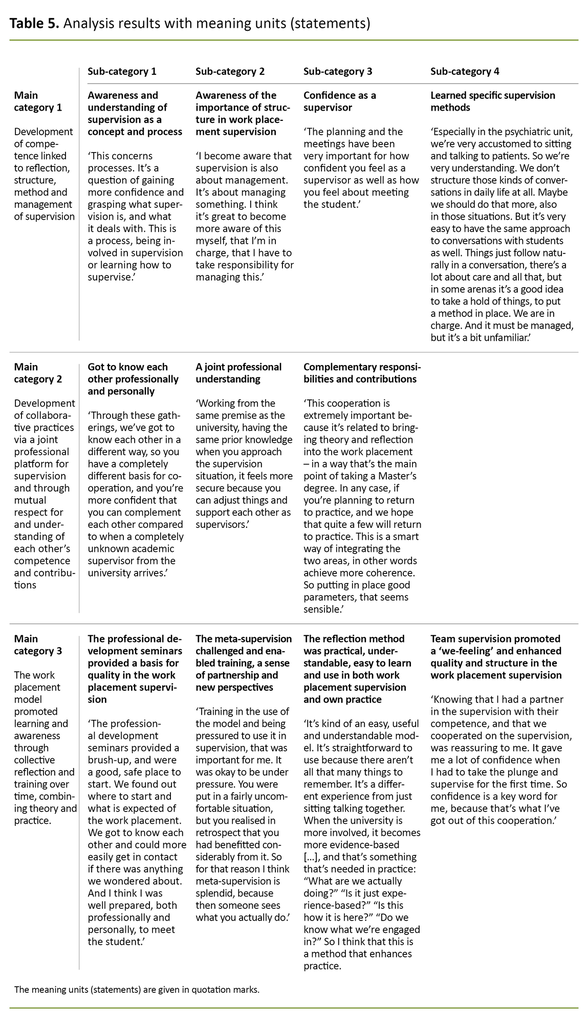

Results: The analysis resulted in three main categories: 1) Development of competence linked to reflection, structure, method and supervision management, 2) Development of collaborative practices via a joint professional platform for supervision and through mutual respect for and understanding of each other’s competence and contributions, and 3) The work placement model promoted learning and awareness through collective reflection and training over time, combining theory and practice.

Conclusion: The objective of the study was to examine experiences gained from a work placement supervision model, with the intention of enhancing the quality of supervision, supervision competence and cooperation. The study showed that joint professional development seminars, meta-supervision and team supervision helped to promote quality and cooperation. The model assumes management support, planning and professional resources. Management support is a prerequisite for achieving cooperation and justifying resource use. The model helped to ensure that work placement supervisors were better prepared to welcome students, and this enhanced the quality of learning.

Universities Norway (UHR) and NOKUT have shown interest in work placements and have issued guidelines to enhance the quality of supervision competence and the level of collaboration between various actors (1, 2). The work placement project, with a focus on the quality of work placements in higher education in health and social science, is one of several national development projects UHR has carried out in this connection, commissioned by the Ministry of Education and Research (1).

The work placement project was a follow-up of the white paper Meld. St. 13 (3) on education for welfare – interaction in practice. This pointed out that the systematic development of supervision competence was one of the key quality-enhancement measures. The regulatory anchoring of standards for formal education in supervision, and better integration of theory and practice were recommended (1).

A new management system for health and social science programmes was established when regulations on a joint framework plan for these programmes entered into force in autumn 2017 (4). The Ministry of Education and Research thus follows up the recommendations of the work placement project: the work placement supervisor must have relevant professional knowledge and should as a main rule have formal supervision qualifications.

The Norwegian regulations concerning supervision of the educational quality in higher education (Academic Supervision Regulations) set out the following requirement for study programmes with mandatory work placements: The institution must ensure that work placement supervisors have relevant competence and experience from the field of practice (5, section 2-3, point 7).

White paper Meld. St. 16 (6) describes work placements as an important learning arena. The link between work placements and teaching at educational institutions is crucial for the quality of the programme of study. In order to ensure relevance and quality, close cooperation between the educational institution and the work placement institution is essential.

The importance of cooperation is highlighted in a number of studies, but little specific detail is given about what thecooperation should comprise, and how it should be organised (7).

Earlier research

A NOKUT report asserts that poor communication between students, educational institutions and work placement institutions affects student learning (8).The report concludes that both students and institutions appear to have an ambivalent attitude to work placements.

The students value the competence they acquire from the work placements but are frustrated by problems that make learning outcomes more difficult to achieve. The educational institutions value work placements because they prepare students for working life and give them practical experience, which they themselves are unable to offer.

The students appear to be unwilling to put in what work placements demand in terms of time, credits, money and quality. NOKUT raises the question of whether work placements in higher education may be much praised but often given little priority (8, p. 58).

A systematic survey of supervision practices in higher education points to challenges linked to key actors, the organisation of the content of study programmes and learning environments at the system level. The author claims that there is reason to believe that failure to address questions related to the organisation of content and system-level impact on the quality of supervision work may result in continued fragmentation and elusiveness in programmes of professional study and the teachers’ professional practice. (9).

A quantitative survey of 1500 respondents concluded that supervision competence was generally poor, the supervisors had little dedicated time for supervision as well as little opportunity to update their knowledge and familiarise themselves with descriptions of student learning outcomes (10).

A focus group study on the quality of supervision from a student perspective showed that students were frustrated by the sub-optimal cooperation between the work placement institution and the educational institution. Work placements were randomly organised and the quality of supervision varied (11).

Student perspectives on work placements also emerged in a focus group study of students in kindergarten teacher programmes. The complex picture that the students paint of the quality of supervision shows that supervisors need more competence (12).

Another focus group study describes the experiences of work placement supervisors with supervision and quality-related challenges. These challenges were linked to the supervisors’ competence, experience and understanding of supervision, and the cooperation between the work placement institution and the educational institution. The authors concluded that there is a need to acknowledge the work placement supervisor role and to give this higher status by introducing competence enhancement measures, establishing a supervisors’ network and peer-to-peer mentoring opportunities (13).

Haukland et al. (14) demonstrated that academic staff had differing understandings of what constituted good supervision in work placements and of the importance of competence in carrying out good supervision. Academic supervisors experienced a greater workload and a conflict of loyalty between following up students and performing other academic work. Managers in the field of practice have an overarching responsibility for academic quality in terms of student supervision.

Uppsata et al. (15) showed what managers in the field of practice believed to be of importance for high-quality student supervision. The managers found the different expectations and requirements challenging. They were faced with contrasting expectations in terms of the responsibility for students and patients, competence needs, competence development and the different systems they had to deal with.

Austenå et al. (16) found that competence enhancement programmes created motivation and helped to boost the quality of work placement supervision for students on intensive courses. They concluded that clearer and closer cooperation between the educational institution and the work placement institution was a prerequisite for enhancing competence in work placement supervision.

In a bachelor degree nursing programme project, Nordhus et al. showed that cooperation between the educational institution and the work placement institution is important in enabling the students to achieve the set learning outcomes (17).

In light of earlier research, there is a need for more studies on new models for work placement supervision.

The work placement supervision model

In the middle of December 2017, the Master’s degree programme in mental health care at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, and the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN) were granted funding for a joint project to develop a model for work placement supervision. The objective was to enhance the quality of student supervision, the competence of work placement supervisors and academic supervisors, and the level of cooperation between the UiT and the field of practice.

This was based on an understanding of supervision as a formal, relational and pedagogical facilitation process aimed at strengthening the skills of the person in question through a dialogue based on knowledge and humanist values (18).

The project group, which consisted of representatives from the specialist and primary health services as well as the UiT, developed and implemented the model, and constituted the reference group for the study. We designed the study after testing the model.

The project group discussed the research question and tentative results, and safeguarded the service user perspective by ensuring that the field of practice was represented. The model was developed and implemented in spring and autumn 2018 as well as in spring 2019. Data were collected in spring 2019.

The objective of the study

The objective was to develop knowledge about the experiences gained from testing the model.

The purpose of the study was to further develop and implement the work placement supervision model in the Master’s degree programme in mental health care.

Research questions

The research questions were as follows:

What are the participants’ experiences in relation to the enhancement of supervision competence, the collaboration between the university and the field of practice, and the work placement supervision model?

Method

Design and method

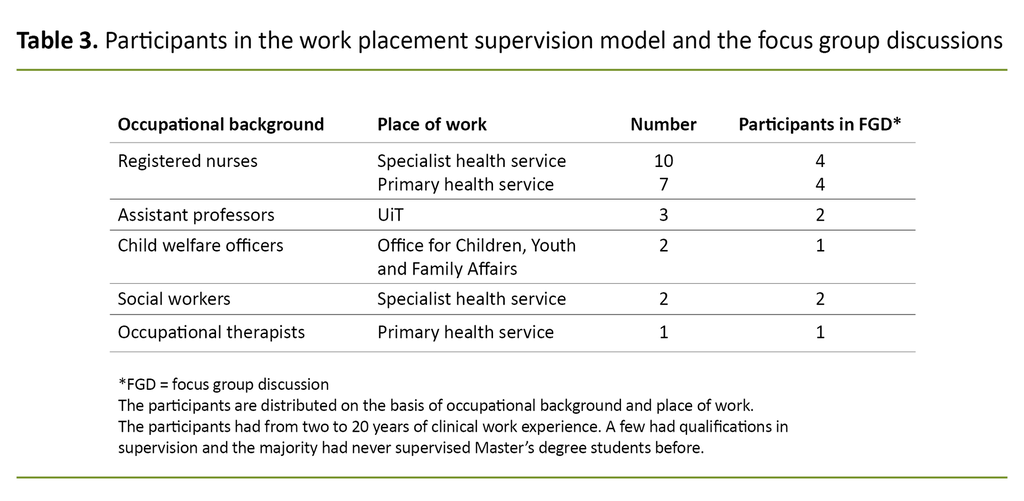

An exploratory and descriptive design was used with a qualitative method of data collection. Focus group discussion was our chosen tool to explore phenomena related to shared experiences and views (20). We used an interview guide with open-ended questions on experiences with the work placement supervision model (professional development seminars, team supervision, meta-supervision and the reflection method). The first author headed the focus group discussions while the second author acted as an assistant.

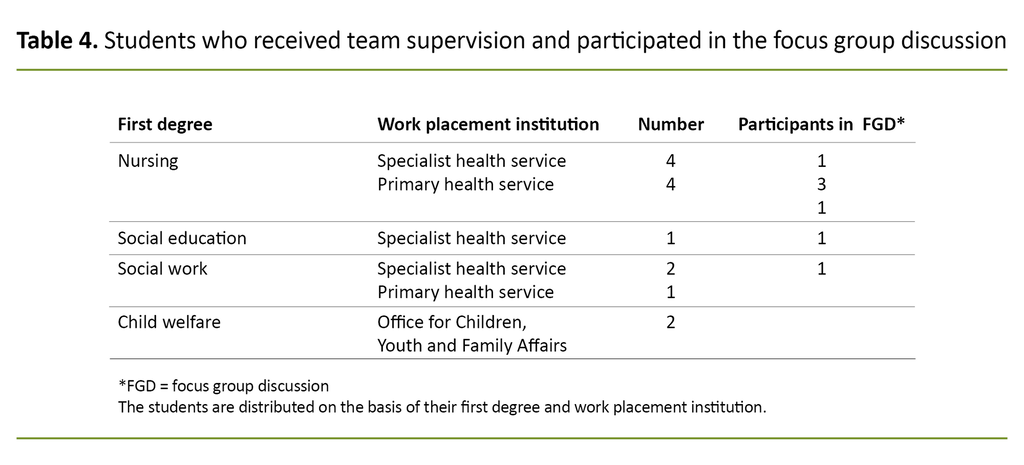

All participants in the work placement supervision model (work placement supervisors and academic supervisors) were invited to take part in the focus group discussions. The work placement supervisors represented the specialist and primary health services and formed two focus groups. In addition, the students formed one focus group since they were the end-users.

The three focus groups, each with five to seven participants, were interviewed once.

Oral information about the study was given at a professional development seminar. The following day, we circulated a written invitation to participate in the focus group discussions together with a consent form. The students were informed about the study and invited to take part in a focus group discussion via the Canvas learning platform.

Those who wanted to participate handed in their consent form when they attended the focus group discussion. These were conducted one-and-a-half months after the testing of the model. The focus group discussions lasted approximately 90 minutes and took place at the work placement institutions and at the UiT.

The participants’ managers allowed the focus group discussions to be held during working hours. The study was approved by the data official for research at the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference number 468671.

The participants gave informed voluntary consent and were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time without further consequences. They were informed that person-identifiable data were subject to confidentiality and would be anonymised when published.

We prepared a risk assessment and a data processing plan (21). The second author transcribed the discussions successively, and the data material amounted to 75 pages.

Analysis

The analysis of the data material was performed as systematic text condensation inspired by Malterud’s description. It consisted of four steps: 1) establish an overall impression, 2) summarise, 3) identify meaning units, and 4) condense and synthesise (22, p. 98).

We analysed the data material together, and the project group and the participants were invited to discuss the tentative results and the further development of the model.

Results

In the following, we present the results. Meaning units (statements) are given in quotation marks.

The results show that the participants had positive experiences of the work placement supervision model. It helped to strengthen supervision competence, the quality of the supervision and the cooperation between the UiT and the field of practice.

Development of competence linked to reflection, structure, method and management of supervision.

The work placement supervisors stated that they had further developed their supervision competence and that this had enhanced the quality of supervision. The participants had developed greater awareness and understanding of supervision as a concept and process as well as related areas of supervision.

One participant said as follows: ‘It became clearer to me when I was giving advice and when I was providing supervision.’ Another participant said: ‘It was very helpful to acquire such competence. I think I will be a better supervisor now.’

Many supervisors felt that supervising Master’s degree students was challenging. This feeling seemed to be related to their own competence and what Master’s degree students were supposed to learn.

The participants had developed greater awareness of learning outcome descriptors: ‘We started to talk about learning outcome descriptors before the students began their work placement, and became more knowledgeable about what Master’s degree students are supposed to learn.’

The importance of having a structure in work placement supervision was one of the topics of the focus group discussions. The structure provided a framework, helped to direct attention and gave room for flexibility. One participant remarked: ‘I used a ‘fishbone structure’ to provide an overview – when you have that, it’s easier to be flexible without losing focus.’

The participants had become more confident in the supervisor role.

The participants had become more confident in the supervisor role, and this impacted on the students’ and supervisors’ outcomes from the work placement supervision. One supervisor said as follows: ‘The student was very pleased! When you see the student’s reaction, both the moment of realisation and the fact that he also feels confident and is able to reflect on and acknowledge his knowledge and skills – this strengthens the student and is of course rewarding for me. I feel that I have achieved something worthwhile.’

Both the work placement supervisors and the academic supervisors emphasised that learning the reflection method was positive and that it strengthened their knowledge and skills, and their attitudes to supervision.

One participant said as follows: ‘I have a clear plan for how to approach it. I know exactly how to act.’ Another participant said: ‘This has increased my supervision competence and I found that the student was really interested.’

Development of collaborative practices via the joint professional platform for supervision, mutual respect and understanding for each other’s competence and contribution

The content of the work placement supervision model helped participants to get to know each other professionally and personally, and to make them feel more secure and to cooperate more successfully. One academic supervisor said: ‘Meeting people from the work placement has made me feel more secure in my role.’

A shared professional understanding was described as a prerequisite and an important basis for strengthening cooperation and providing good supervision. One work placement supervisor explained: ‘Meeting each other and talking together beforehand is really important for ensuring a robust process with the students. We’re working on the same premise as far as our supervision methods go, and in terms of who should introduce what – the work placement institution or the university.’

Another participant said: ‘There’s a need and a potential here. I think it’s important for the future that we see the usefulness of this kind of cooperation.’

In the work placement model, the work placement supervisors and the academic supervisors complemented each other in terms of responsibilities and contributions. The participants had acquired greater understanding and awareness of what they could contribute as supervisors and how they could complement each other.

One participant said: ‘This project – the cooperation between the work placement institution and the university – was really spot on. We need academia and they need us to ensure that students receive good training.’

The work placement model promoted learning and consciousness-raising through shared reflections and practice over time, combining theory and practice.

Professional development seminars were important in establishing a joint professional platform and as an arena where work placement supervisors and academic supervisors could become better acquainted. Such seminars promoted better cooperation between the university and the field of practice, and higher quality supervision.

One work placement supervisor said as follows: ‘I have gained more knowledge about what supervision is, and how it takes place. I have found it extremely useful to have the theoretical segment as a basis – as well as the tools we received and practice in their use.’

Meta-supervision challenged and enabled training, a sense of partnership and new perspectives. It provided a good opportunity to practise the reflection method and receive feedback on one’s own supervision. The challenges were related to practising new skills in front of others and daring to show uncertainty, as well as being confronted with unexpected input.

A number of participants had never been in a situation where they had received comments from others on their own supervision practice. Some of them pointed out the parallels between the process of taking part in the work placement supervision model and being a student in a work placement:

‘For me, it was instructive to participate and compare my own role here and now with the student’s role. We are actually taking part in the same process; we are being challenged. That’s positive. Now I need to assess whether there’s anything I need to work on or want to work on, or what I should do now.’

Both supervisors and students described the reflection method as practical, understandable, easy to learn and use. The discussions showed that the students could find that theory and practice were disconnected, while the reflection method helped to unite theory and practice.

The ethical reflections were also regarded as extremely useful. Both supervisors and students pointed out that the reflection method was also useful in their own practice in terms of patient safety. One participant said: ‘It’s so incredibly important in practice to have a bird’s-eye view. What are we actually doing?’

Team supervision promoted a ‘we-feeling’, and enhanced quality and structure in the work placement supervision.

Another participant said: ‘Boosting the level of reflection, reflecting on things from many perspectives – I think that’s incredibly important for patients as well. We can become tangled in prejudices and misery – that’s quite possible with our very sick patients. It’s important to get more of an overview of the situation, see it from different angles, and not least focus on the ethical perspective. How does the patient experience this? This is urgently needed in this field of practice. There aren’t many unoccupied beds in hospitals, and people have multiple disorders. It’s easy to lose your way in different ways of understanding. We need reflection.’

Team supervision promoted a ‘we-feeling’, and enhanced quality and structure in the work placement supervision. Both work placement supervisors and academic supervisors found that they complemented each other in team supervision, and that this interaction impacted on the quality of supervision. One academic supervisor said as follows:

‘Knowing that I had a partner in the work placement setting with their competence, and that we cooperated on the supervision, was reassuring to me. I believe that this model will give the students additional outcomes. They will have an additional forum where they can present issues. The close cooperation meant that I felt more secure, and that we could more easily identify anything that didn’t work very well. It was a quality assurance.’

The students were interviewed as end users. They had found that the work placement supervision model enhanced the quality of supervision. The focus group discussions also showed that the students had a need for a professional development seminar about supervision prior to the work placement. They suggested arranging a joint induction day for students and supervisors where they could be introduced to the reflection method and practice using it together before the work placement.

Discussion

The results show that the participants had positive experiences with the work placement supervision model in relation to competence enhancement, quality of supervision and cooperation. The participants regarded the model as useful and as meeting a recognised need.

Competence enhancement

The results indicate that participants had acquired a greater awareness of what supervision is, the related areas, what structure means, and the importance of learning outcome descriptors. The work placement supervision model promotes competence enhancement and greater confidence in the supervision role.

Several studies document the significance of supervision competence for the quality of the supervision (9), as does the summary report on the challenges and opportunities related to quality in practice (2). However, the model assumes that providers of professional development seminars and meta-supervision already possess supervision competence.

The students stated that the competence the supervisors gained through the model helped to enhance the quality of the supervision.

While the regulations on a joint framework plan for health and social science programmes (4) stipulate that the work placement supervisor must have supervision competence, this does not apply to academic staff.

The students taking part in the focus group discussions stated that the competence the supervisors gained through the model helped to enhance the quality of the supervision. They also said that they themselves wanted to have such competence. The competence of the supervisors has a positive impact on the students’ learning outcomes (2, 23).

The participants asserted that improved supervision competence provided them with a tool for reflection on their own practice, which also enhanced the quality of their work with patients in terms of guidance. Supervision competence is generic, and can be adapted to different target groups (1, 24).

Cooperation

The work placement supervision model set focus on the UiT in the field of practice, and meant that work placement supervisors were keener to cooperate. Academia seemed to come closer. The model stimulated a joint understanding of supervision and shared methods, which boosted cooperation.

When they shared supervision duties, they realised that they had different kinds of knowledge and that both were needed. The boundaries were broken down and supervision became more transparent for both parties, which in itself represents a form of quality assurance. Notably, cooperating on supervision is in keeping with the concept of integrating different competencies (9, 25).

The focus group discussions showed that the transition from further education in mental health care to the Master’s degree programme created challenges. These challenges mostly concerned whether students taking a Master’s degree are seeking to distance themselves from clinical work, so that the supervision is futile.

There was also uncertainty as to whether supervisors without a Master’s degree could supervise Master’s degree students. These challenges may be related to a knowledge hierarchy: Which kind of knowledge counts for most: academic knowledge or clinical knowledge?

Again we see the importance of integrating competencies (9, 25) and cooperation. Hauge et al. (26) concluded in their study that cooperation between the study programme and the field of practice is a pre-requisite for quality assuring work placements.

The work placement supervision model

The work placement supervision model promoted competence enhancement, and boosted the quality of supervision and cooperation. The participants learned through theory, own activities and situated learning. A number of learning theorists highlight the importance of participating in real-life situations (27–31).

Professional development seminars, meta-supervision and team supervision require that participants meet, and this requires long-term planning and coordination on the part of both the UiT and the work placement institution.

The importance of joint professional development seminars is an important finding in the study.

The model assumes management support in both institutions. Managers have overarching responsibility for the quality of student supervision, competence enhancement for staff and facilitating supervision (5, 6, 15, 32).

What does management support entail? At an executive level, it concerns establishing appropriate agreements between the institutions in respect of responsibilities, financial arrangements and use of time. It also concerns management support related to quality and attention to supervision, time for supervision, supervision competence and competence enhancement (13, 15).

The importance of joint professional development seminars is an important finding in the study. Here participants get to know each other, acquire a joint professional platform and practice new skills together.

Joint professional development seminars were an important prerequisite for creating the trust necessary for taking on board meta-supervision and creating equality between the work placement supervisor and the academic supervisor in team supervision. Since the UiT organised full-day seminars, it was important to exploit the opportunities offered by the model.

Method critique

There was a limited number of participants in the three focus groups. This was the maximum number we were able to gather. We examined our own field, developed the work placement supervision model and headed the focus group discussions. These factors may have influenced the participants to give favourable remarks.

One strength of the study is that the project group provided input to the model, the research questions, analysis and results.

Despite weaknesses in the methods, we believe that the results are transferable to other Master’s degree programmes with work placements and Bachelor’s degree programmes. The results also provide a sound basis for developing the model further.

Conclusion

The objective of the study was to examine experiences gained from using a work placement supervision model with the intention of enhancing the quality of supervision, supervision competence and cooperation.

The study demonstrates that joint professional development seminars, meta-supervision and team supervision helped to enhance quality and supervision. The model must be supported by management and requires planning and professional resources. Such support is essential to achieving cooperation and justifying the use of resources.

Through the model, work placement supervisors were better prepared to welcome students, which enhanced learning quality. The model can be further developed through giving students the same training. In addition, the responsibility for organising and implementing the model could be assigned to specific individuals in the field of practice and at the educational institution.

Sincere thanks to Nina Foss, then head of studies, for her valuable input in our work on this article.

References

1. Universitets- og høgskolerådet. Kvalitet i praksisstudiene i helse- og sosialfaglig høyere utdanning. Praksisprosjektet. Sluttrapport fra et nasjonalt utviklingsprosjekt gjennomført på oppdrag fra Kunnskapsdepartementet i perioden 2014–2015. Oslo: Universitets- og høgskolerådet; 2016. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/86921ebe6f4c45d9a2f67fda3e6eae08/praksisprosjektet-sluttrapport.pdf (downloaded 07.03.2020).

2. Nokut – Nasjonalt organ for kvalitet i utdanninga. Kvalitet i praksis – utfordringer og muligheter. Samlerapport basert på kartleggingsfasen av prosjektet «Operasjon praksis 2018–2020». Oslo: Nokut; 2019. Available at: https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/nokut/rapporter/ua/2019/kvalitet-i-praksis-utfordringer-og-muligheter_16-2019.pdf (downloaded 07.03.2020).

3. Meld. St. 13 (2011–2012). Utdanning for velferd. Samspill i praksis. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2012. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-13-20112012/id672836/ (downloaded 07.03.2020).

4. Forskrift 6. september 2017 nr. 1353 om felles rammeplan for helse- og sosialfagutdanninger. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2017-09-06-1353 (downloaded 16.02.2020).

5. Forskrift 7. februar 2017 nr. 137 om tilsyn med utdanningskvaliteten i høyere utdanning (studietilsynsforskriften). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2017-02-07-137 (downloaded 07.03.2020).

6. Meld. St. 16 (2016–2017). Kultur for kvalitet i høyere utdanning. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2017. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-16-20162017/id2536007/?ch=1 (downloaded 07.03.2020).

7. Tveiten S, Iversen A. Veiledning i høyere utdanning. En vitenskapelig antologi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018.

8. Nokut – Nasjonalt organ for kvalitet i utdanninga. Til glede og besvær – praksis i høyere utdanning. Oslo: Nokut; 2018. Rapport 2 – 2018. Available at: https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/nokut/rapporter/ua/2018/hegerstrom_turid_til_glede_og_besvar_praksis_i_hoyere_utdanning_3-2018.pdf (downloaded 07.03.2020).

9. Zlatanovic T. Veiledning i læreprosesser i helse- og sosialfaglige utdanninger – en litteraturoversikt. In: Tveiten S, Iversen A, eds. Veiledning i høyere utdanning. En vitenskapelig antologi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018. pp. 21–35.

10. Norsk Sykepleierforbund (NSF). Stor vilje – lite ressurser. Rammebetingelser for veiledning av sykepleierstudenter i kommunehelsetjenesten. Oslo: NSF; 2018. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/3895428/cache=20182205132729/Praksisrapport%20endelig%20mai%202018.pdf (downloaded 07.03.2020).

11. Johannesen A, Onstad RF, Tveiten S. Hun må jo reflektere sammen med meg. Et studentperspektiv på kvalitet i veiledning i praksisstudier. In: Tveiten S, Iversen A, eds. Veiledning i høyere utdanning. En vitenskapelig antologi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018. pp. 67–83.

12. Worum KS, Bjørndal CRP. Studenters oppfatninger av god og dårlig praksisveiledning i barnehagelærerutdanning. Nordisk tidsskrift i veiledningspedagogikk. 2018;3(1):1–17. Available at: https://boap.uib.no/index.php/nordvei/article/view/1578 (downloaded 07.03.2020).

13. Onstad RF, Nordhaug M, Iversen A, Skommesvik S, Haukland M, Uppsata SE et al. Kvalitet i praksisveiledning – en vedvarende utfordring? Erfaringer fra praksisveiledere. In: Tveiten S, Iversen A, eds. Veiledning i høyere utdanning. En vitenskapelig antologi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018. pp. 86–102.

14. Haukland M, Gjerlaug AK, Skommesvik S, Uppsata SE, Flittie RO, Tveiten S et al. Å jenke det til. Vitenskapelig ansattes forståelse av veiledning i praksisstudier. In: Tveiten, Iversen A, eds. Veiledning i høyere utdanning. En vitenskapelig antologi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018. pp. 105–19.

15. Uppsata SE, Iversen A, Skommesvik S, Nordhaug M, Onstad RF, Haukland M et al. I en akseptert skvis mellom systemkrav og kvalitetskrav? Lederes perspektiv på kvalitet i praksisveiledning. In: Tveiten S, Iversen A, eds. Veiledning i høyere utdanning. En vitenskapelig antologi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2018. pp. 121–35.

16. Austenå M, Høybakk J, Nyhagen R, Sjøgren M, Sørensen AL, Heggdal K. Styrking av veileders kompetanse i utdanning av intensivsykepleiere. Nordisk sygeplejeforskning. 2019;9(4). Available at: https://www.idunn.no/nsf/2019/04/styrking_av_veileders_kompetanse_i_utdanning_av_intensivsyk (downloaded 06.05.2020).

17. Nordhus GEM, Skagøy BS, Alnes RE. Medisinske praksisstudier i forsterket sykehjemsavdeling, Nordisk sygeplejeforskning. 2019;9(4). Available at: https://www.idunn.no/nsf/2019/04/medisinske_praksisstudier_i_forsterket_sykehjemsavdeling (downloaded 15.05.2020).

18. Tveiten S. Veiledning – mer enn ord. 5th ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2019.

19. Tveiten S. The public health nurses’ client supervision [Doctor's thesis]. Medisinsk fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo; 2006.

20. Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2012.

21 Universitetet i Tromsø – Norges arktiske universitet (UiT). Informasjonssikkerhet og personvern ved UiT. Tromsø: UiT. Available at: https://uit.no/om/informasjonssikkerhet (downloaded 11.12.2020).

22. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

23. Jansson I, Ene KW. Nursing students’ evaluation of quality indicators during learning in clinical practice. Nurse Education in Practice. 2016;20,17–22.

24. Vågan A, Raaen, FD, Ødegaard NB, Rajka L-GK, Tveiten S. Helsepedagogikk i læreplaner: en didaktisk analyse. Uniped. 2019;42(04):368–80.

25. Zlatanovic T. Nurse teachers at the interface of emerging challenges [Doctor's thesis]. Oslo: Oslomet – storbyuniversitetet; 2018.

26. Hauge KW, Brask OD, Bachmann L, Bergum IE, Hegdal WM, Inderhaug H et al. Kvalitet i praksisstudier i sykepleier- og vernepleierutdanning. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning. 2016;1(12):19–33.

27. Wenger E. Communities of practice. Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

28. Grendstad NM. Å lære er å oppdage. Oslo: Didakta Norsk Forlag; 1986.

29. Dewey J. Democracy and education. Middelsex: The Ecco Library; 2007.

30. Dysthe O, ed. Ulike perspektiv på læring og læringsforskning. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 1999.

31. Dysthe O, ed. Dialog, samspel og læring. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag; 2001.

32. Kårstein A, Caspersen J. Praksis i helse- og sosialfagutdanningene. En litteraturgjennomgang. Oslo: Nordisk institutt for studier av innovasjon, forskning og utdanning; 2014. NIFU-rapport nr. 16. Available at: https://nifu.brage.unit.no/nifu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/280127/NIFUrapport2014-16.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (downloaded 07.03.2020).

Comments