Routine screening for postpartum depression puts mental health on the agenda

When public health nurses use the EPDS screening tool in addition to their gut feeling and clinical judgment, they identify more mothers who need help.

Background: This research project was drawn up in light of the implementation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) as a routine part of Trondheim local authority’s plan for antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care.

Objective: We conducted interviews with eight public health nurses in order to explore their experiences with using the EPDS as a tool to screen for postpartum depression in new mothers.

Method: A qualitative approach with thematic analysis was used.

Results: In the analysis process, we identified four key themes: the perception that ‘screening puts mothers’ mental health on the agenda’, that the subject of postpartum depression screening is considered less invasive when screening is a standard routine for all new mothers, that ‘the EPDS picks up on what the gut feeling misses’ and that ‘clinical judgment is used as an important supplementary tool’ in the EPDS screening.

Conclusion: The findings from this study support earlier research showing that the EPDS is a valuable tool in the screening for postpartum depression, and that mandatory screening makes it easier to broach subjects related to mental health. Furthermore, this study shows the importance of public health nurses using their clinical judgment when screening for postpartum depression.

A total of 10–15 per cent of mothers experience symptoms of depression after childbirth (1, 2), known as postpartum depression and often referred to as postnatal depression (3). Postpartum depression is different from the ‘baby blues’, which is so common that it is considered to be a normal condition.

If this condition is particularly overwhelming and does not pass quickly, healthcare personnel should be vigilant. In such cases, it is often a public health nurse or midwife at the child health centre who will pick up on this, as hospital stays after childbirth tend to be short (4).

It is important to identify postpartum depression as quickly as possible so that the woman can receive help at an early stage. If it goes undiagnosed, the condition can worsen and last longer, leading to major consequences for the mother herself, for the child and for the mother’s partner (1).

Postpartum depression can impact on the interaction between a mother and her infant (5), and is associated with impatience, hostility, and low sensitivity (6). Postpartum depression is also a risk factor for behavioural problems, emotional problems, cognitive problems, poorer physical health, and linguistic and social challenges in children (7–9).

Clinical judgment

Clinical judgment in nursing relates to professional judgments, but also to general common sense; the silent knowledge and wisdom used in the everyday work (10).

In recent years, clinical judgment has been side-lined by the growing focus on the use of standardised screening tools in the health service (11). Skard (11) claims that standardised tools have been introduced to prevent misdiagnosis, but if used incorrectly, they can result in both overtreatment and incorrect treatment.

However, research has shown that experienced clinicians are less likely to act in accordance with the scores from such standardised tools and more likely to make a comprehensive and complex discretionary assessment of the patient (12).

Problems related to mental health are not directly verifiable, and healthcare personnel therefore need to use both clinical judgment and their gut feeling (11).

In a review of studies dealing with the identification of mental health problems associated with pregnancy, both intuition and screening tools were highlighted as important resources (13).

Screening for postpartum depression

Midwives and public health nurses use several different methods in their work on postpartum mental health. Although screening tools often help facilitate this work, other factors constitute barriers, such as time constraints, lack of training and referral options (13).

In addition to work pressure and lack of knowledge about postpartum depression, fear of offending mothers or making them feel uncomfortable is also a major barrier (14). Internationally, concern has been expressed about routine screening as it is difficult to assess the positive health benefits or the risk of mistakenly categorising women as depressed (15).

Norwegian studies of public health nurses have found that using screening tools increases job satisfaction levels, improves professional confidence, and means the nurses are more likely to seek help (16). Several instruments are available for screening for postpartum depression. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is the most frequently used tool worldwide (18).

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

The EPDS is a self-report questionnaire consisting of ten short statements with four response options, in which the new mother chooses the answer that best corresponds to how she has been feeling over the past seven days (17).

The screening, together with a follow-up support conversation, is known as the Edinburgh method. The EPDS was originally developed so that healthcare personnel without specialist expertise in mental disorders could screen for symptoms of depression in mothers (3).

The screening tool does not cover physical ailments that can be common in depression, such as changes in sleep, appetite, libido, fatigue and low energy (1). This is because such symptoms may be a result of childbirth and the responsibility of caring for a new-born child.

The EPDS is a validated instrument that is easy to use and therefore useful for screening for depression (18, 19). The total score ranges from 0–30, and according to the EPDS manual (3), anyone who scores more than twelve should be followed up.

Norwegian studies have shown that a threshold value of ten intercepts everyone who is depressed, but that there are also a significant number of false positives, where those who are not depressed are also included (18). A two-step screening process, in which two measurements and an interview decide whether further referral is necessary, has been proposed as a method to more accurately identify those who actually need help (20).

Since early interventions are most effective, it is important to intercept mothers’ low moods as quickly as possible.

The EPDS is not a diagnostic tool, and mothers with high scores are referred for further assessment, usually through their GP. Despite the debate about threshold values, it is widely agreed that the support conversation following the screening is vital in deciding what action should be taken (21, 22).

The consequences of postpartum depression can be very severe and can affect the child’s social and emotional development, but it can be successfully treated (4, 23). Since early interventions are most effective, it is important to intercept mothers’ low moods as quickly as possible.

Objective of the study

The EPDS was established by Trondheim local authority as a routine part of the six-week check-up and incorporated into the Plan for Antenatal, Intrapartum and Postpartum Care in Trondheim Municipality 2015–2018. Evaluation of the use of the screening tool is one of the measures outlined in the plan for 2019–2022 (24).

The purpose of our study was to explore public health nurses’ experiences with using the EPDS as a universal screening tool.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health’s national guidelines state that there should be a procedure for screening for postpartum depression (25), but there is currently no universal screening in Norway. The guidelines do not mention how screening should take place.

Early screening is important in order to prevent negative consequences for the mother and child (1), and in the worst case, suicide (26). The benefits that can be gained from using the EPDS depend on professionals being comfortable with this method of screening for symptoms of depression (22).

This study aims to take an in-depth look at the experiences of healthcare personnel using the tool as part of the mandatory screening for postpartum depression.

Method

Design and sample

The study has a qualitative approach with semi-structured interviews.

The sample consisted of eight public health nurses, the majority of whom have several years of experience in screening for postpartum depression. Experience in using the EPDS was one of the inclusion criteria, and all informants had been trained in using the instrument.

Length of service as a public health nurse varied considerably between the informants. One had worked for less than three years, while at the other end of the scale, one had almost 40 years of experience.

Data collection

Informants were recruited in cooperation with Trondheim local authority, through a contact person who passed on information about the project to the unit managers and head public health nurses in four districts. We were given the names of public health nurses who wished to participate.

These were contacted and sent information letters, and two public health nurses from each of the four districts were interviewed in the autumn of 2017. Prior to the interviews, we discussed the best way to manage our own pre-conceptions of the topic of mental health in order to avoid asking leading questions.

The interview guide consisted of overarching questions in addition to several in-depth follow-up questions: ‘Can you tell me a bit about how you work on screening for low moods in new mothers?, ‘What do you think about carrying out such screening?’ and ‘Can you give an example of a situation [...]’.

Our emphasis was on obtaining the greatest possible variation related to both positive and negative experiences with screening. The interviews were recorded using a dictaphone and subsequently transcribed into written form verbatim. The second and third authors conducted the interviews and transcribed them, while all three authors participated in the analyses.

Ethical considerations

The study was reported to and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (project number 54814). We removed directly identifiable data from the transcripts and followed the guidelines for storing and deleting data. Written consent was obtained from informants.

We emphasised, both in the information letters sent by e-mail and at the interviews, that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. We also notified informants that it would not be possible for them to withdraw their consent after the anonymisation process was completed.

Analysis

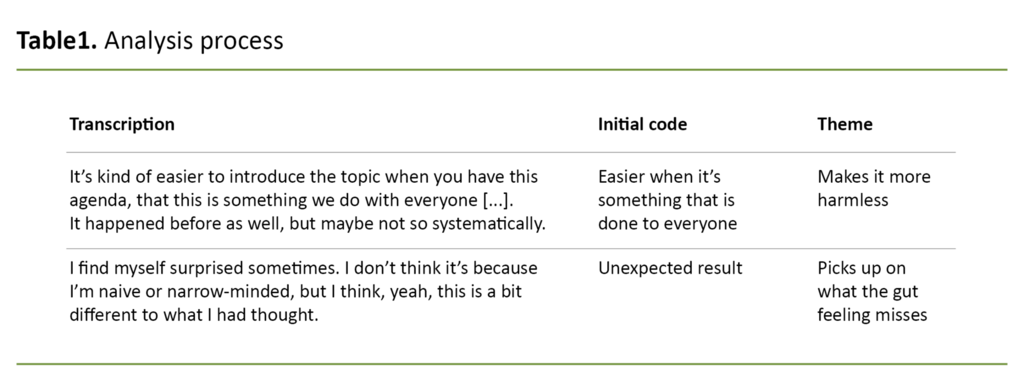

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data material. The thematic analysis consisted of six steps (27), the first of which was to familiarise ourselves with the data material by thoroughly reading all the interview transcripts several times. Step two entailed initial coding, where text segments were given labels.

In step three, we searched for themes by reviewing the codes from step two. Table 1 shows an extract of the analyses. In step four, we evaluated the themes to see if they had to be split, merged or rejected. In the fifth step, we identified the essence of what each topic was about, while the final step was the report writing (27).

The themes that emerged from the analysis were as follows:

- Screening puts mothers’ mental health on the agenda

- Less invasive when screening is a standard routine for all mothers

- Picks up on what the gut feeling misses

- Clinical judgment is a supplementary tool

Results

In the presentation of the analysis results, we have given the various public health nurses pseudonyms for the sake of transparency.

Screening puts mothers’ mental health on the agenda

All informants felt that the implementation of the EPDS screening tool had provided a framework and made it easier to raise issues related to mothers’ mental health, both as a port of call during the meetings with the new mothers and as a deep dive into mothers’ mental health.

The following quote describes the perception that the EPDS puts mothers’ mental health on the agenda:

‘There can certainly be things that both the doctor at the child health centre and the public health nurse overlook that come out when using the tool [EPDS]. Plus, doing it [...] puts talking about mental health on the agenda.’ (Klara)

Several informants indicated that the EPDS sets a framework for the conversation, and ensures that participants stick to the topic and that mental health is not forgotten. The EPDS creates a space for mothers’ mental health to be the sole focus, regardless of the child’s rash and any vaccines.

The screening makes the mother aware that the child health centre cares about her mental health.

Through mental health being put on the agenda and earlier involvement of public health nurses, they considered themselves to be in a better position to prevent low moods:

‘I think maybe, maybe just putting it into words and talking about it, that it can be a good thing. Whether it has a preventive effect or not, but [...] at least it makes it easy to raise the subject. There shouldn’t be any kind of threshold, no, we don’t talk about such things because this is maybe just about me.’ (Agnes)

The screening makes the mother aware that the child health centre cares about her mental health, which may make her more likely to seek help:

‘Well, yes, in a way you’re more open to things. I think it might be helpful for mums to see that a public health nurse can open up, and be more interested in how they’re feeling. That it’s easier to come back and talk about things. Because there’s probably a lot of people who don’t know what we do at the child health centre. It’s all about the baby. Even though we’re also concerned about the health of mother, and father. That says a lot, I think.’ (Anna)

Less invasive when screening is a standard routine for all new mothers

The majority of informants referred to the benefit of the screening being an integral part of the public health nurses’ work, making it easier to broach the subject of mental health with mothers.

The fact that everyone was asked the same questions made it less challenging in the conversation situation: ‘I think it’s good that there is such a standard method that is used for everyone regardless of language.’ (Fredrikke)

The clear expectation for public health nurses to set aside time for screening meant that the screening framework was structured, and the fact it was a standard feature of their work that everyone would be involved in made them feel more assured:

‘And I also think that such a very clear guide to when we should bring things up, means that it gets done, so when we follow-up on mental health in the six-week check-up, it’s not just a question that’s automatically included, because if it was it might easily be swamped by the user’s wishes.’ (Louise)

The barriers to raising the topic were lower because all mothers were to be screened, and the public health nurses therefore managed to intercept more. The fact that the barriers were lower is illustrated in the following quote:

‘It’s kind of easier to introduce the topic when you have this agenda, that this is something we do with everyone [...]. It happened before as well, but maybe not so systematically. Then it was more that we, if you saw something that made you wonder. But now it’s kind of a bit more systematic, because you talk to everyone about it.’ (Ellinor)

Picks up on what the gut feeling misses

Several informants felt that the implementation of the EPDS has led to recognition that gut feelings and clinical judgments are an important aspect of the job, but that the gut feeling is not enough in some situations.

Several pointed out that it is not always possible to identify low moods and depression in conversations with mothers, and that the EPDS can serve as a good aid.

In the past, they considered whether to screen for low moods based on their gut feeling during the conversation with the mother, but since the introduction of the EPDS they now screened everyone for low moods, regardless of their gut feeling.

Many also brought up instances where they had found that their gut feeling had let them down and that the screening with the EPDS had been essential.

The following quote from an experienced public health nurse clearly describes how she found that gut feelings and intuition are not always enough to identify a mother’s low moods:

‘I find myself surprised sometimes. I don’t think it’s because I’m naive or narrow-minded, but I think, yeah, this is a bit different to what I had thought. And being maybe a bit aware, that it’s maybe not always easy to spot, and it’s not always that we can see through everyone, we can’t read everyone, and we have very different ways of expressing ourselves, so it’s not certain that I catch them. So I think that it [EPDS] can certainly be used to help us with this a bit.’ (Louise)

Many also brought up instances where they had found that their gut feeling had let them down and that the screening with the EPDS had been essential. When one of the public health nurses was asked to give an example of such a situation, she described the following:

‘She smiled and [...] you very often see, you know, whether people are doing okay or not. But then I was really surprised, I had completely failed to notice, if I hadn’t used the EPDS, I would have just thought that she was fine, and they were fine, and here everything is hunky dory.’ (Inger)

Another public health nurse also described how her gut feeling had let her down, and how, without the EPDS, she would not have managed to identify low moods or depression in some of the mothers:

‘I’ve probably thought a few times that [...] I’ve had a bit of a surprise. Oh! Once we’ve filled out the form, the EPDS questionnaire. Because I was thinking, here’s a mother who looks happy, smiling and is clearly very [...] nothing. And then she’s filled out the questionnaire and I’m flabbergasted. Oh, you’re not doing so well. So it’s been helpful. Maybe it’s also been easier for them to mark it on a form than to say it.’ (Anna)

Clinical judgment is a supplementary tool

Common to all the informants was their experience of being able to ‘sense’, or tell by looking at a mother, if she was doing well, and that this gut feeling had been a major factor in how they had approached the conversation about the screening. Several described situations where their gut feeling was that the mother had low moods but that the results from the EPDS had indicated the opposite:

‘You listen to how they’re doing, and then it may be that they have a low score, but nevertheless you’ve realised, maybe before, or afterwards, that they have, that you think there’s something more here. Everything’s not okay despite them getting a low score, you know.’ (Dagny)

After the mother has completed the EPDS questionnaire, it is the public health nurse’s job to assess what follow-up is needed. In such contexts, they often used their gut feeling or clinical judgment:

‘Even if they have a low score, you might see during the conversation that there’s a bit more to it, it can go either way. You can think, yeah, this here isn’t very serious, there’s a simple explanation for this. But then you can get those who might not get such a high score, but as you continue, you start to feel a bit concerned after all.’ (Ellinor)

Most of the public health nurses did not slavishly adhere to the threshold values; the assessment of further follow-up and treatment was also based on gut feeling and clinical judgment.

Discussion

There can be several reasons why it is challenging to broach the subject of mental health with new mothers. Work pressure and lack of time are major barriers (13), while others shy away from addressing the issue (14).

The public health nurses in this study found that the routine screening with the EPDS put them in a better position to protect the mothers’ mental health, thus helping to prevent a negative development in the child.

The benefits of using the EPDS that were identified in this study are consistent with other studies, which found that using the EPDS helps to focus on the mother’s mental health and interaction with the child and raises awareness among parents that the child health centre is also there to help the parents, not just the child (16).

Healthcare personnel are afraid of causing offence

Public health nurses considered postpartum depression to be something that has come to be perceived as harmless because ‘everyone experiences it’, making it easier to raise the topic of mental health with the mothers. Healthcare personnel’s fear of causing offence or making the mother feel uncomfortable is often a barrier to broaching the subject of mental health (14).

Universal screening of all mothers seems to reduce that barrier for the informants. The expectations related to their tasks are clarified through universal screening, which in turn creates a structure for the screening framework.

Universal screening could help strengthen the screening and lead to more mothers with symptoms of depression being identified at an early stage. The mother’s challenges become more apparent to her as she has to complete the questionnaire herself, and the screening makes her aware that the child health centre is interested in her mental health.

This awareness may make her more likely to seek help. Other studies have also emphasised that the barriers to asking for help are reduced as a result of routine screening with the EPDS (16), and that the reduced barriers to seeking help will be of value as mothers often feel ashamed of having low moods after childbirth (1).

Healthy mothers can be categorised as depressed

Routine screening can potentially have negative sides, including the risk of categorising healthy mothers as depressed (15).

All of the public health nurses in the study stated that they feel they can tell by looking at a mother whether she is struggling, and that clinical judgment is vital in deciding how to protect the mother’s mental health.

Some of the informants gave examples of situations where the EPDS has shown a low score, but where they nevertheless considered the mother to have a low mood.

The public health nurses’ practices are consistent with research that points out that screening for low moods does not throw up a clearly defined textbook answer, and that depression, like all other mental disorders, is not a directly verifiable disorder that can be definitively measured using a standardised tool such as the EPDS (11).

In order to prevent incorrect treatment and unnecessary use of resources, it is important that the value of the public health nurses’ clinical judgment is emphasised. However, their gut feeling and clinical judgment are not always sufficient, and in such situations, the EPDS is a useful and important tool.

The post-screening conversation with mothers

The informants described how the EPDS screening is followed up with a conversation where they go through the scores with the mother, and that this post-screening conversation is essential. These findings are supported by research that shows it is important that the content of this conversation forms part of the basis for deciding what happens next (3, 18).

The importance that public health nurses attach to the post-screening conversation is also consistent with research showing that the EPDS only gives an indication of depressive symptoms, and that the support conversation is essential for assessing whether the results indicate postpartum depression (22).

Cox (22) emphasises that it is important for users of the tool to feel comfortable with it. Mandatory screening entails extra work in an already busy working day.

The informants had no negative experiences from working with screening.

All the public health nurses in the study considered the EPDS to be a good tool that makes it easier to bring up subjects related to the mother’s mental health. This finding is consistent with other studies (19), even though we had expected there to be some negative experiences related to, for example, time constraints (13).

The informants had no negative experiences from working with screening. Adequate training is crucial for the successful introduction of routine screening (16). All the informants had received training, which may help to explain the absence of negative experiences.

The perception that the EPDS provides a clear framework and a good structure for screening mothers’ mental health is a key finding of the study. Objections to the routine screening of postpartum depression often relate to disagreements about cut-off scores and the risk of incorrectly categorising someone as depressed (15, 20).

The findings from this study suggest that public health nurses’ use of clinical judgment is important in situations where the instrument does not identify depression in the mother, and that routine screening using the Edinburgh method facilitates a greater focus on mental health beyond the actual screening for depression.

Method discussion

Our background in psychology means we have a fundamental belief that it is extremely important to focus on postpartum depression, and, prior to the interviews, we therefore discussed how our understandings of the topic, i.e. our preconceptions, could affect the results.

During the interviews, we therefore asked about negative experiences related to the screening and actively sought in the analyses to find examples that contradicted the results. Semi-structured interviews will never be infallible; various sources of error, such as a desire to portray oneself in a positive light, can present themselves.

Only eight public health nurses were interviewed, and we cannot rule out that a larger sample would have given a greater variation in experiences. The fact that the screening is universal and an integral part of the local authority’s plan may have affected the results, and the local authority’s participation in the recruitment may have made the informants feel that the degree of confidentiality was insufficient.

Despite the limitations, we believe that the findings correspond closely with similar studies of the EPDS in Norway (19), which supports the validity of the study.

Conclusion

The public health nurses considered the EPDS to be a good framework for screening for postpartum depression, and also for putting the spotlight on mothers’ mental health in general.

The introduction of mandatory screening has enhanced their ability to base their assessments on more than just clinical judgment, which helps them identify more people who need help.

However, the findings have also shown that it is important for health nurses not to ignore their gut feelings and clinical judgments, since the EPDS is not always able to intercept all cases of low moods in mothers. Routine screening with the EPDS tool seems to reduce public health nurses’ barriers to raising topics related to mental health.

References

1. Eberhard-Gran M, Slinning K, Rognerud M. Screening for barseldepresjon – en kunnskapsoppsummering. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2014;3:297–301.

2. O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

3. Cox J, Holden J, Henshaw C. Perinatal mental health: the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Manual. 2. utg. London: Royal College of Psychiatrist Publications; 2014.

4. Slinning K, Eberhard-Gran M. Psykisk helse i forbindelse med svangerskap og fødsel. In: Moe V, Slinning K, Hansen MB, eds. Håndbok i sped- og småbarns psykiske helse. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2010. p. 323–46.

5. Eberhard-Gran M, Slinning K. Nedstemthet og depresjon i forbindelse med fødsel. Oslo: Nasjonalt folkehelseinstitutt; 2007.

6. Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–92.

7. Junge C, Garthus-Niegel S, Slinning K, Polte C, Simonsen TB, Eberhard-Gran M. The impact of perinatal depression on children’s social-emotional development: a longitudinal study. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2017;21(3):607–15.

8. Liu Y, Kaaya S, Chai J, McCoy D, Surkan P, Black M, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2017;47(4):680–9.

9. Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(1):1–27.

10. Dåvøy GM. Skjønn er evident. Klinisk Sygepleje. 2007;21(3):21–8.

11. Skard HK. Et vitenskapelig skjønn. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening. 2017;54(3):294–300.

12. Eells TD, Lombart KG, Kendjelic EM, Turner LC, Lucas CP. The quality of psychotherapy case formulations: a comparison of expert, experienced, and novice cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapists. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):579.

13. Noonan M, Galvin R, Doody O, Jomeen J. A qualitative meta-synthesis: public health nurses role in the identification and management of perinatal mental health problems. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2017;73(3):545–57.

14. Higgins A, Downes C, Monahan M, Gill A, Lamb SA, Carroll M. Barriers to midwives and nurses addressing mental health issues with women during the perinatal period: the mind mothers study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(9–10):1872–83.

15. Harris L. Screening for perinatal depression: a missed opportunity. The Lancet. 2016;387(10018):505.

16. Vik K, Aass IM, Willumsen AB, Hafting M. «It's about focusing on the mother's mental health»: screening for postnatal depression seen from the health visitors' perspective – a qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2009;37(3):239-45.

17. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6.

18. Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Schei B, Opjordsmoen S. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation in a Norwegian community sample. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;55(2):113–7.

19. Glavin K, Ellefsen B, Erdal B. Norwegian public health nurses' experience using a screening protocol for postpartum depression. 2010;27(3):255–62.

20. Eberhard-Gran M, Slinning K, Rognerud M. Screening for postnatal depression – a summary of current knowledge. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening. 2014;134(3):297–301.

21. Ben-David V, Jonson-Reid M, Tompkins R. Addressing the missing part of evidence-based practice: the importance of respecting clinical judgment in the process of adopting a new screening tool for postpartum depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2017;38(12):989–95. DOI: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1347221

22. Cox J. Use and misuse of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): a ten point ‘survival analysis’. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2017;20(6):789–90.

23. Cuijpers P, Weitz E, Karyotaki E, Garber J, Andersson G. The effects of psychological treatment of maternal depression on children and parental functioning: a meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;24(2):237–45.

24. Trondheim kommune. Temaplan. Svangerskaps-, fødsels- og barselomsorgen i Trondheim kommune 2019–2022. Available at: https://www.trondheim.kommune.no/globalassets/10-bilder-og-filer/04-helse-og-velferd/jordmor/temaplan---svangerskaps--fodsels--og-barselomsorgen-i-trondheim-kommune-2019---2022.pdf (downloaded 23.04.2020).

25. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonale retningslinjer for diagnostisering og behandling av voksne med depresjon i primær- og spesialisthelsetjenesten. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2009. IS-1561. Available at: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/voksne-med-depresjon/Voksne%20med%20depresjon%20%E2%80%93%20Nasjonal%20retningslinje%20for%20diagnostisering%20og%20behandling%20%20i%20prim%C3%A6r-%20og%20spesialisthelsetjenesten.pdf/_/attachment/inline/ed0d2ef2-da11-4c4e-9423-58e1b6ddc4d9:961cda6577d48345aa0d6fe9642b6b6acc2a6506/Voksne%20med%20depresjon%20%E2%80%93%20Nasjonal%20retningslinje%20for%20diagnostisering%20og%20behandling%20%20i%20prim%C3%A6r-%20og%20spesialisthelsetjenesten.pdf (downloaded 16.04.2020).

26. Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8(2):77–87.

27. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101.

28. Brennan PA, Hammen C, Andersen MJ, Bor W, Najman JM, Williams GM. Chronicity, severity, and timing of maternal depressive symptoms: relationships with child outcomes at age 5. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(6):759.

29. Netsi E, Pearson R, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske M, Stein A. The long term course of persistent and severe postnatal depression and its impact on child development. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;75(3):247–53.

30. Campbell SB, Brownell CA, Hungerford A, Spieker SJ, Mohan R, Blessing JS. The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(2):231–52.

Comments