Nursing students develop cultural competence during student exchanges in Tanzania

The students gain an increased understanding of cultural differences by maintaining an open attitude and receiving explanations of cultural differences that they do not understand.

Background: Globalisation has led to increased migration, and nursing students need cultural competence in order to meet the health challenges that can arise in a multicultural society. Student exchanges are an effective learning method for developing cultural competence because the students encounter people in a different cultural context over time.

Objective: To gain an insight into nursing students’ personal experiences with developing cultural competence during a student exchange in Tanzania.

Method: We conducted focus group interviews with nursing students taking part in a three-month exchange in Tanzania.

Results: Development of cultural competence was dependent on the students being given explanations of aspects they did not understand and having their attitudes challenged. They developed an increased understanding by participating in cultural encounters with people over time and by reflecting on their personal experiences. Maintaining an open attitude in their cultural encounters with people and situations combined with a willingness to go outside their comfort zone also helped the students to develop cultural competence.

Conclusion: The students who took part in a three-month exchange developed cultural competence by maintaining an open attitude and obtaining explanations that gave them an increased understanding of cultural differences. More research is needed on teaching programmes that can help strengthen the students’ cultural competence.

Globalisation has created a need for cultural competence in nursing (1). With a goal of providing patient-centred nursing irrespective of cultural background, the development of cultural competence has become a topical issue in nursing education, both nationally and internationally (2–4). Report no. 16 to the Storting (4) emphasises that nursing education must teach students to be active, sought-after and responsible participants in the international community.

In order to ensure equality in services for all groups in society, the proposal in the National Regulations relating to a Common Curriculum for Health and Social Care Education states that students should develop cultural competence during the course of their education. Cultural competence can be defined as ‘the ongoing process in which the healthcare professional continuously strives to achieve the ability and availability to work effectively within the cultural context of the patient’ (2).

Cultural competence requires cultural encounters with people, where the competence is developed through five components:

- awareness of own cultural prejudices;

- knowledge of cultural and ethnic groups;

- skills in cultural assessments;

- encounters with people from a different cultural background, and

- a desire to develop cultural awareness (5).

Nurses need more knowledge about culture and skills within cultural assessment. The nursing education needs to focus more on culture through strengthening the student’s ability to assess how culture impacts on the patient’s situation (2, 3, 6).

A review article on the cultural competence of healthcare professionals shows that such competence increases significantly following interventions involving training in cultural competence, and that this increase is significantly associated with patient satisfaction (7).

Extended student exchanges are the most effective

Student exchanges that stretch over a significant period are one of the most effective ways of developing cultural competence because students are immersed in a different culture over time. They are ‘foreigners’, which gives them a clear perspective from which to see the differences between cultures (8–10). However, a meta-analysis of short-term student exchanges of two to four weeks indicates no improvement in cultural understanding (11).

Analyses of 350 reflection notes written by 197 Norwegian nursing students during a three-month clinical placement in Africa revealed a low level of cultural understanding among the students (12, 13). Several studies indicate that students exhibit a paternalistic or ethnocentric attitude in their encounters with people from a different culture, and that the student exchange poses ethical challenges (10, 14, 15).

Student exchanges in Tanzania

Since 2008, Norwegian nursing students have had the opportunity to undertake part of their clinical studies in the bachelor’s degree in nursing at Tanga International Competence Centre (TICC) in Tanzania (16). TICC focuses on sustainable development of the local community, and has established twelve development programmes in health and education for vulnerable groups.

In the exchange programmes, the students participate in clinical practice at health clinics, day centres, school health services and retirement homes, and in mental health services in home nursing and outpatient clinics.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain an insight into nursing students’ personal experiences with developing cultural competence during a three-month exchange in Tanzania. The research question was as follows:

What are Norwegian nursing students’ experiences with developing their cultural competence during a three-month student exchange in Tanzania?

Method

In order to gain an insight into nursing students’ personal experiences with developing cultural competence, we chose an inductive, qualitative approach with focus group interviews. The focus group interviews are suitable when participants have a common background of experience (17). The experiences of students in their encounters with people from a different culture provided a good basis for the kind of discussion and conversation engendered by a focus group interview.

Focus groups provide supplementary information through the informants’ dialogue with each other, and the discussion in the group can bring to light diversity and nuances (17). The group is headed by a moderator, and a facilitator helps to conduct the interview. The authors shared these roles.

Sample and interview

The sample in the study was strategic, and recruitment took place among 25 nursing students who were undertaking a student exchange at TICC in autumn 2015. TICC’s study section sent out the invitations to participate, and 21 students; 19 of whom were women, from three learning institutions agreed to take part. For practical reasons, the participants were divided into four groups.

We conducted the focus group interviews at TICC, where the students lived, at a point when the students had completed 9 of their 12 weeks in a clinical placement. We devised the interview guide in line with the objective of the study, where the main questions were: (i) ‘What do you think of when you hear the term “cultural competence”?’ (ii) ‘What is your personal experience with developing cultural competence? Give examples.’

The interviewers asked in-depth questions about the students’ experiences from the exchange in general and their clinical placement experiences in particular, with a view to understanding the students’ personal experiences with developing cultural competence. The interviews were audiotaped and lasted between 65 and 80 minutes.

Analysis

We analysed the data using thematic content analysis, where the first step involved a systematic reading of all the interviews in order to gain an overall impression. We then noted the meaning behind the sentences, paragraphs and verbal exchanges, and coded them accordingly. Coding often leads to a categorisation that entails the meaning being reduced to a few categories (18). The coding was carried out by both authors separately.

We then discussed the resultant codes. During our discussion, we systematised the categorisation into overarching thematic categories and subcategories. This process summarised the meaning behind all of the codes within each category. We did not focus on which student said what, but on what was commonly expressed across the four focus groups. We used data from all four interviews.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the former Norwegian Social Science Data Services (reference number 44841), now called the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (19). Before the interview started, the students received oral and written information about the study and how they could withdraw. They then signed a declaration of consent.

No names are given in the material, and we deleted the audio recordings after transcription in order to protect confidentiality. The study did not involve any Tanzanian people. We therefore decided that there was no need for ethical approval from the National Health Research Ethics Sub-Committee (NatHREC).

Results

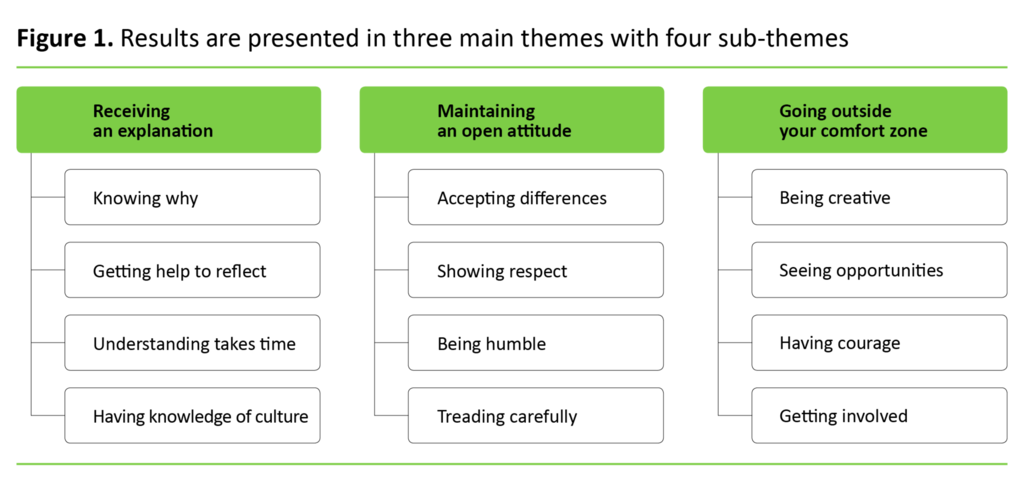

The interviews with the students highlighted three main themes as central to their personal development of cultural competence (Figure 1).

Receiving an explanation

In all the interviews, the students brought up the importance of knowledge as a means of developing cultural competence, and they emphasised the significance of explanation and understanding. One student expressed the following: ‘If you know something about the culture you are immersed in, it’s much easier to show understanding and respect, and to work together and generally carry out the clinical placement.’

The students gave several examples of how explanations helped them gain more insight into the culture and to better understand situations. One student commented as follows: ‘Someone explains something to you, and it then makes sense.’

Another student, who had experienced a situation in which she reacted negatively, said the following: ‘I’m given an explanation, or I realise that in this situation, that’s the best solution. And then I understand they are doing the best for the patient... Even if we would do it in a completely different way in Norway. But that’s because we have much more resources.’

When situations were explained to the students, they changed their attitudes to people and situations. One student involved in a home visit to a psychiatric patient who was tied to the bed said: ‘You go in with the attitude that this is not acceptable. We don’t do this in Norway. Then suddenly the situation is explained to you, and you can see the other side, and then you think that maybe this is sort of acceptable after all.’

The students experienced a variety of situations that were alien and incomprehensible to them, and their initial emotions and reactions sometimes changed after they were given an explanation and gained new insight. One student described the change as follows: ‘Once you know why they’re doing something differently, you stop going around being annoyed about it.’

Clinical supervisors provided explanations in the clinical placement and in the compulsory daily reflection groups. The students emphasised the importance of reflection as a means of developing cultural competence. One student made the following observation: ‘Reflection makes us more aware of what we have seen, done and experienced in the clinical placement. Without it, it would be a case of: you don’t quite know why you reacted like this or why you did that, but when we talk about it, we become more aware, which is a good thing.’

In the beginning, the students often reacted negatively to what they experienced. However, they understood more as time passed. It takes time to accept other attitudes, behaviour and methods, with one student commenting as follows: ‘At first there was a lot for me to think about, and that I spent energy being annoyed about, but now I have – I don’t know if it’s good or bad, but I’ve gradually accepted that that’s just how it is.’

Maintaining an open attitude

The students felt that it was important to have an open attitude and accept differences before travelling to a country with a different culture. One student described cultural competence as follows: ‘Accepting that it’s not like home, but that it’s different. Try not to turn it into a problem, just accept it. Ask ‘why?’ in order to get an understanding of their reasons for doing it that way.’

The students nevertheless stressed that it was not always necessary to agree with what the locals did in order to show understanding. For example, they reacted to the healthcare professionals’ attitudes to the patients. However, with time and experience they accepted it for what it was. The students also spoke about gender disparities they reacted to, but which they accepted. They tried to show respect by not interfering in such situations.

One student told of situations where children were physically punished: ‘That’s not permissible in Norway under any circumstances, but we can’t tell them that it’s wrong because we are outsiders in a way. We’re not part of their culture, we can’t just barge in, so we try to tread carefully.’

The students were conscious of treading carefully and being humble in their cultural encounters with people who thought, lived and worked in other ways. One student expressed the following: ‘We must take a little care not to offend the healthcare professionals here. We need to be humble and think about things differently, and not assume that we are right.’

By proceeding with care, the students felt that they were showing respect: ‘We cover up when we go out in order to respect their culture and how they view women and the body.’ The students pointed out that they were simply visitors, and they linked the development of cultural competence to showing respect and being humble in their cultural encounters with others.

One student made the following observation: ‘I think it's important to be humble. I’m a student on a clinical placement here. It’s important to find new ways to think about situations and view things in a different perspective. They have a different structure, economy and culture and ... I feel we have learned a lot and grown personally and gained cultural competence.’

Outside the comfort zone

The students said that it was no good being reserved if they wanted to get acquainted with and gain an insight into a different culture. They were challenged to go outside their comfort zone, and several said that they had changed considerably. Among other things, they described how they had participated in singing and dancing in health education campaigns at schools and in villages – something they would never have done in Norway.

Many students said they had discovered new sides of themselves through the challenges they had faced in clinical placements and daily life, but that they would not see the consequences of this for a while. As examples, the students discussed how they demonstrated more courage and determination in the clinical placement situations than they would have done before. They were more independent, took charge more and suggested measures in patient situations: ‘I think I’ve toughened up a bit too – more likely to get stuck in.’

Several students said they often had to improvise and be creative, especially given the lack of resources. One student described this as follows: ‘Seeing the possible in the impossible.’

The students undertook a one-week course in Swahili at TICC before starting the clinical placement, but this was not enough to enable them to communicate in Swahili in daily life. They therefore had to be independent and creative when communicating with others. One student described this as follows: ‘Thinking for yourself, thinking outside the box and reading people.’

Several students described how they tried to follow local customs, even though they were new to them. One student told of their experience in a patient situation: ‘... and not always to be so priggish about it and just give it a try. Eat the food they eat and drink what they drink! So I started to just dive in and do the same. It created such a good atmosphere. Then the other students began to get on board and follow suit.’

Discussion

The objective of the study was to gain an insight into nursing students’ experiences with how they developed cultural competence during a student exchange in Tanzania. The students linked this development to receiving explanations of situations that they found challenging or difficult to understand, and to maintaining an open attitude in their cultural encounters with people and situations. They also emphasised that their willingness to go outside their own comfort zone was essential for developing cultural competence.

Time, knowledge and reflection foster awareness of personal values and contribute to increased cultural competence (7, 10, 20). In the supervision, aspects of clinical placement situations that the students reacted to or did not understand were explained or put into a cultural context.

Such explanations included how the health service was organised, what factors impacted on the service, how the local healthcare professionals assessed and treated various conditions, such as mental disorders, and why they used coercion.

The explanations could also be linked to the role patterns that existed in the family, where the father or the oldest male in the house made decisions on behalf of the household members. Through acknowledging the circumstances, the students increasingly tried to participate in patient situations instead of critically observing them from the sidelines.

Developed a new understanding

The students’ personal knowledge, skills and attitudes were constantly being challenged, and they had to negotiate with the people they encountered (2). Campinha-Bacote (2) presents the LEARN mnemonic (List, Explain, Acknowledge, Recommend, Negotiate), which describes the professional assessment nurses make when interacting with patients who have a different cultural background to their own.

The LEARN process is demonstrated in the students’ descriptions of their personal development up to the point of acknowledging persons with a different cultural background. Through their personal experiences, reflections and dialogues with people, they developed new understandings and attitudes, and an acknowledgement of the differences in the cultures.

However, they did not develop competence that enabled them to make recommendations and negotiate with the people they met in the clinical situations. This was partly because the role of student was limited in terms of responsibility and opportunities for following up patients or service users. Another reason was that they did not have sufficient professional competence to ask critical questions in the dialogues they had with people in clinical situations.

Linguistic challenges

A third factor that restricted the students’ ability to be involved in the last two elements of LEARN was their lack of language skills in Swahili. Language has a large impact on human interaction, and the students described how they often used nonverbal communication or a supervisor and interpreter when there were language barriers.

Nonverbal communication is not always sufficient when interacting with patients and assessing their situation in cases where making recommendations and negotiations are essential elements for achieving patient satisfaction, for example (7). Some interpreters were qualified healthcare workers and supervisors with extensive clinical experience, but they were not responsible for patient care.

In cases where patients only spoke Swahili, the students were not proficient enough in the language to interact with the patients without an interpreter. In view of this and the role of student in a foreign culture, the students’ contribution to assessing patients was therefore limited. Developing cultural competence takes time (2). The students’ development of cultural competence and ability to carry out a professional assessment in a different culture must therefore be considered in light of the short time they participated in the culture.

A desire to develop cultural awareness

A desire to develop cultural awareness is a key factor in developing cultural competence (5, 21), and the students expressed this desire, partly through their open attitude in cultural encounters with people. This mindset contributed to personal development, and strengthened their confidence in their abilities. Personal development and a sense of mastery are essential learning outcomes of student exchanges (10, 22, 23).

In her review article on how nursing students benefit from student exchanges, Kelleher (22) concludes that ‘participation in a study abroad experience is associated with many benefits for nursing students, including various forms of personal and professional growth, cultural sensitivity and competence, and cognitive development’ (p. 690).

Several studies (10, 22, 23) do not describe what level or degree of competence the students have achieved after taking part in a student exchange. The students in our study did not mention this either, but several of them stated that they had a greater learning outcome from the exchange in Tanzania than from their clinical placements in Norway.

Culture needs to be an integral part of the education

In order for nursing students to develop cultural competence as part of their nursing education, the cultural aspect should be an integral part of the learning process and not something that is only brought up in some university classes. One measure that has proven to be effective is to conduct workshops for staff and students (24, 25). More research is also needed on what factors impact on the students’ learning outcomes from student exchanges (11, 22, 26).

In addition to the importance of language skills and personal development, the development of cultural competence can be linked to the content of the partnership between the institutions, the organisation of the exchange programme, the student role, the duration of the exchange and the process that takes place when the students interact with people in the local community (27–29).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study presents the development of cultural competence from the student’s perspective; something that has not been studied previously as far as we are aware. A further strength of the study is that the experiences we present in this article are from students from three different learning institutions in Norway. The students had a common understanding of the process of developing cultural competence, and the findings concur with earlier research.

The focus group was an appropriate method because it created opportunities for dialogue, and several students said that sharing their experiences with fellow students gave them valuable feedback. It is open to debate whether we could have learned about other experiences by using a theory-driven interview guide with points from the theory of cultural competence.

The study only covers the experiences of Norwegian students in one exchange country. Several of the studies we refer to were conducted in the USA, but we have not discussed differences in culture and education systems. The students in this study lived with up to 70–80 other Norwegian students in a centre founded and run by Norwegians.

In addition, the centre is physically isolated from the local community. It would have been useful to explore the importance of exchanges between Tanzanian and Norwegian culture in more depth in the interviews. The exchange between two cultures and the degree of proximity to the local culture can impact on the benefits and level of cultural competence gained from the exchange.

Conclusion

The students strengthened their cultural competence during the exchange period. Communication and interaction with people who had a different cultural background to their own supported this process. Receiving explanations of aspects they found difficult to understand contributed to the development of their cultural competence. The students emphasised that the ability to maintain an open attitude and go outside their comfort zone was essential for developing cultural competence.

It was crucial for them to have the opportunity for organised reflection on their personal experiences in order to strengthen their cultural competence. The student exchange did not, however, contribute to developing competence that enabled the students to make recommendations and negotiate with people they met in the clinical placements.

It takes time to develop cultural competence, and language skills, the role of student as well as the length and content of the exchange programme are some of the factors that impact on the process. There is therefore a need for more research on teaching programmes that strengthen students’ cultural competence.

References

1. Leininger MM, McFarland MR. Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, research and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

2. Campinha-Bacote J. Delivering patient-centered care in the midst of a cultural conflict: The role of cultural competence. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(2).

3. Magelssen R. Hva lærer fremtidige sykepleiere om migrasjon & helse? En kartlegging av bachelorstudiet i sykepleie i Helse Sør-Øst. Oslo: Nasjonal kompetanseenhet for minoritetshelse; 2012.

4. Meld. St. nr. 16 (2016–2017). Kultur for kvalitet i høyere utdanning: Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2017. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-16-20162017/id2536007/(downloaded 05.04.2017).

5. Campinha-Bacote J. Coming to know cultural competence: An evolutionary process. International Journal for Human Caring. 2011;15(3):42–8.

6. Alpers L-M, Hanssen I. Caring for ethnic minority patients: A mixed method study of nurses' self-assessment of cultural competency. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(6): 999–1004.

7. Govere L, Govere EM. How effective is cultural competence training of healthcare providers on improving patient satisfaction of minority groups? A systematic review of literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(6):402–10.

8. Greatrex-White S. Uncovering study abroad: foreignness and its relevance to nurse education and cultural competence. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28(5):530–8.

9. Maltby HJ, de Vries-Erich JM, Lund K. Being the stranger: Comparing study abroad experiences of nursing students in low and high income countries through hermeneutical phenomenology. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45(10):114–9.

10. Edmonds ML. An integrative literature review of study abroad programs for nursing students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(1):30–4.

11. Gallagher RW, Polanin JR. A meta-analysis of educational interventions designed to enhance cultural competence in professional nurses and nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(2):333–40.

12. Hovland OJ, Johannessen B. What characterizes Norwegian nursing students’ reflective journals during clinical placement in an African country? International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2015;2:47–52.

13. Johannessen B, Hovland OJ, Steen JJ. Topics Norwegian nursing students are concerned with during clinical placement in an African country: Analysis of reflective journals. International Journal for Human Caring. 2014;18(3):7–14.

14. Burgess CA, Reimer-Kirkham S, Astle B. Motivation and international clinical placements: Shifting nursing students to a global citizenship perspective. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2014;11(1):1–8.

15. Stys D, Hopman W, Carpenter J. What is the value of global health electives during medical school? Med Teach. 2013;35(3):209–18.

16. TICC. Tanga International Competence Center [internett]. WordPress.com [updated 05.05.2017, cited 05.04.2017]. Available at: https://meetingpointtanga.wordpress.com/.

17. Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2012.

18. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

19. NSD. Norsk senter for forskningsdata [internett]. Bergen: NSD [updated 04.04.2017, cited 05.04.2017]. Available at: http://www.nsd.uib.no/.

20. Chambers D, Thompson S, Narayanasamy A. Engendering cultural responsive care: a reflective model for nurse education. Journal of Nursing Education & Practice. 2013;3(1):70.

21. Dudas KI. Cultural competence: An evolutionary concept analysis. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(5):317–21.

22. Kelleher S. Perceived benefits of study abroad programs for nursing students: an integrative review. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52(12):690–5.

23. Kohlbry PW. The impact of international service-learning on nursing students' cultural competency. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(3):303–11.

24. Wilson A, Sanner S, McAllister LE. A longitudinal study of cultural competence among health science faculty. J Cult Divers. 2010;17(2):68–72.

25. Bohman DM, Borglin G. Student exchange for nursing students: Does it raise cultural awareness'? A descriptive, qualitative study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(3):259–64.

26. Edgecombe K, Jennings M, Bowden M. International nursing students and what impacts their clinical learning: Literature review. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(2):138–42.

27. Ouma BDO, Dimaras H. Views from the global south: Exploring how student volunteers from the global north can achieve sustainable impact in global health. Globalization and Health. 2013;9(1):1–6.

28. Birch AP, Tuck J, Malata A, Gagnon AJ. Assessing global partnerships in graduate nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(11):1288–94.

29. Kulbok PA, Mitchell EM, Glick DF, Greiner D. International experiences in nursing education: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2012;9(1):1–21.

Comments