Public health nurses make active use of a parental guidance programme in their practice

Public health nurses make active use of the International Child Development Programme (ICDP) in their work to improve the interaction between parents and children.

Background: Positive interaction between children and their caregivers is essential for children’s development. Norwegian health policies emphasise the role of child health centres in improving such interaction. It is therefore crucial that public health nurses have expertise in promoting positive interaction.

Objective: To investigate public health nurses’ experiences with using the skills they gained from their training in the parental guidance programme known as the International Child Development Programme (ICDP) during their continuing education in nursing.

Method: The study is qualitative and based on seven semi-structured, individual interviews with public health nurses who have been trained in the programme, but who only apply parts of the programme in their work at the child health centres. We analysed the data using content analysis inspired by hermeneutic interpretation and text condensation.

Results: The participants appear to use the ICDP in consultations, both as a conceptual framework for interaction and as a tool in their observation, communication, guidance and documentation.

The experiences of the public health nurses can be summarised in three main categories:

The ICDP has provided the public health nurses with a useful conceptual framework.

The public health nurses put emphasis on enhancing the parents’ perception of their own competence.

The public health nurses focus on the parents’ ability to see and understand their child.

Conclusion: When the public health nurses do not implement the ICDP in the form of structured group meetings over an eight-week period, they still apply the knowledge and way of thinking from the programme in their communication and guidance when observing children and parents.

The relationship between children and their caregivers early in life is important for children’s development, quality of life and health throughout their lifetime (1–3). Public health nurses have contact with the youngest children and their families through child health centres. It is essential that the health-promoting work of public health nurses encourages positive interaction between parents and children. National guidelines for child health centres and the school health services (4) identify parental guidance as a development-promoting and preventive psychosocial service that encourages positive interaction.

There is solid evidence that parental support programmes have a positive impact (5–7). In Norway, the International Child Development Programme (ICDP) is one of the frequently used parental guidance programmes. Since 2010, about 120 public health nurses have been certified in ICDP as a part of their continuing education.

The parental guidance programme ICDP

The ICDP is a relatively simple preventive programme for improving social interaction. The ICDP is used in many countries (8, 9), and the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs uses the programme frequently. The ICDP was developed by professors Karsten Hundeide and Henning Rye of the University of Oslo in the 1980s and 1990s as a way of translating research into practice.

They based their work in part on knowledge about children as active participants in social interaction (10, 11) and on the findings that parents’ own ideas and feelings affect how they act towards their children (12, 13). The main focus of the programme is to help children by enhancing the parents’ competence in caregiving. This is done by acknowledging what parents are doing well, activating their sensitivity and increasing their understanding of their child.

The ICDP consists of principles for sensitising parents and three dialogues: the emotional, the meaning-creating and the regulatory. The dialogues are divided into eight guidelines for good quality interaction:

- Show positive feelings – show that you love your child.

- Adjust yourself to your child and follow your child’s lead.

- Talk to your child about his/her interests.

- Praise and acknowledge your child for what he/she is able to do.

- Draw attention to shared experiences.

- Create meaning by describing experiences with emotion and enthusiasm.

- Elaborate on and explain shared experiences.

- Make plans together and set boundaries in a positive manner.

The programme is carried out under the direction of a certified ICDP facilitator with eight weekly group meetings of 1.5 to 2 hours involving parents or other caregivers. Emphasis is placed on sensitising the parents through individual activity, participation and reflection (8).

An evaluation of the ICDP showed a positive impact on the interaction between parents and their children (14). The basic components of the ICDP were used together with a trauma approach in a randomised, controlled study during the war in Bosnia in the 1990s (15). The results indicated that the children of mothers who took part in the group intervention had better physical, cognitive and emotional health than the control group after six months.

The effect of the entire programme with eight group meetings has previously been evaluated based on the experiences of parents (14, 16). We found only one peer-reviewed study that investigated the experiences of ICDP facilitators (17). This study concludes that there are challenges entailed in implementing the programme in its entirety. This finding corresponds with the feedback we received from public health nurses in the field of practice who are certified ICDP facilitators. They explain that they are seldom able to hold eight parent group meetings as part of the ICDP programme, but that they use the methodology in their interactions with parents at the child health centres. We found no peer-reviewed studies in our literature search that provided any information about how the ICDP was used when the nurses did not conduct eight weekly group meetings.

Objective of the study

The objective of our study was to gain knowledge of the public health nurses’ experiences with how they applied and benefited from their ICDP parental guidance expertise in their interaction with parents and children in their ordinary consultations at the child health centres.

Method

Design

To try to understand the public health nurses’ experiences with how they applied and benefited from their ICDP facilitator expertise in their interaction with parents and children at the child health centres, we chose to use a qualitative method and conducted seven semi-structured interviews.

We asked the following research questions:

- What are the public health nurses’ experiences with using their ICDP facilitator expertise?

- According to the nurses, how can they promote positive interaction between parents and their children?

Participants

The study participants were seven public health nurses certified in the ICDP parental guidance programme who worked at child health centres. To recruit participants, the lead author sent an email with information about the study to randomly selected public health nurses from three previous classes of nursing students in three different counties. The first eight nurses who gave a positive response to the inquiry and worked at a child health centre, but who did not apply the entire ICDP programme, were invited to participate. Only one of those asked to participate declined to take part.

Conducting the interviews

The lead author conducted all the interviews in the period from May to June 2016. The interviews lasted about one hour and were held at the workplaces of the individual nurses. The following is an example of the questions we asked: ‘What are your main concerns in consultations with regard to parent-child interaction?’ Follow-up questions were, for instance: ‘How do you do that?’ and ‘How do the parents respond to that?’

The interviews were recorded on a dictaphone and transcribed in their entirety. The interviews took the form of a dialogue using an appreciative approach, while at the same time we interpreted the informant’s statements during the dialogue.

Analysis

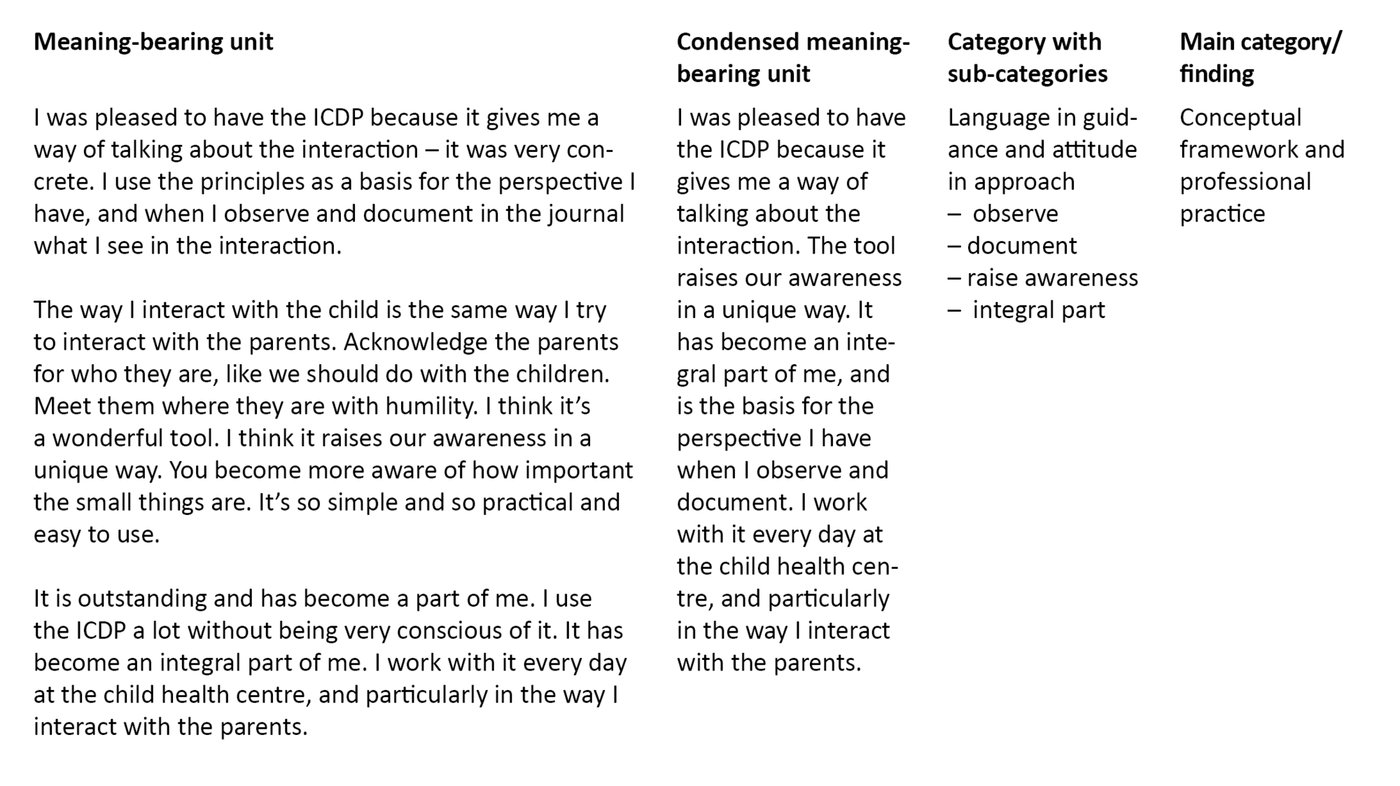

The lead author analysed the text in a four-step procedure using systematic text condensation with an interpretive approach (18) (Table 1). In the first step, the lead author read the material numerous times and took notes on her reflections before writing down her overall impression and identifying preliminary themes.

On the basis of these themes, she reviewed the text again in step 2 by coding the content with different colours as she noticed a new theme in the text. She identified seven themes. The text segments that made the individual themes meaningful were removed from the original context and sorted under each individual theme (decontextualisation).

In step 3, the text under the seven preliminary themes was condensed by shortening each statement, while simultaneously ensuring that the meaning and content of the text was preserved. In addition, the lead author reviewed all the condensed text and sorted the seven themes into five categories with sub-categories.

In step 4, the lead author reviewed the condensed text in light of the research questions. The categories and sub-categories were reorganised into three main categories that comprised the essence of the condensed material. The lead author then prepared an analytical text that described and gave meaning to these three categories, which are described as findings.

The second author reviewed the transcribed interviews again. She looked for other possible themes and interpretations. In the final step, all the authors reviewed the material one more time and discussed it to see whether the findings from step 4 corresponded with the original content of the interview material.

Ethical considerations

The participants signed an information and consent form prior to the interviews. The audio recordings of the interviews were stored in a secure location and deleted after they were transcribed. The recordings did not contain personal information, the informants could not be identified, and the project was not required to submit reports to the Norwegian Data Protection Authority. We made sure to use an appreciative approach during the interviews, and the participants said that they had a positive experience.

Results

We present findings from the study using three main categories that describe how the ICDP facilitator expertise is applied and beneficial in consultations at the child health centres with a view to promoting positive interaction between parents and their children:

- The ICDP has provided the public health nurses with a useful conceptual framework

- The public health nurses put emphasis on enhancing parents’ perception of their own competence.

- The public health nurses focus on the parents’ ability to see and understand their child.

The ICDP has provided the public health nurses with a useful conceptual framework

The public health nurses said that the guidance they provide to parents in consultations at child health centre is usually situational and short term in nature. They explained that the ICDP has given them a conceptual framework and tools for their daily work and that they use these in their observations, communication, guidance and documentation. Several of them said that they have integrated the ICDP components into their professional practice:

‘I use the principles as a basis for the perspective I have.’

‘I’m pleased to have the ICDP because it gives me a way of talking about the interaction.’

Although they used all the ICDP guidelines in their professional and personal approach to parents and when advising them, the nurses highlighted two factors in particular: 1) praise and acknowledgement, and 2) how to understand the child. The nurses stressed the importance of praising and acknowledging the parents for what they did well in order to develop a good relationship with them.

The public health nurses believed that acknowledgement has significance for their ability to step into the role of parental adviser and for being able to address difficult topics during the conversation: ‘I’m very focused on what they do well, and what I see is positive. They are then more open to discussing the difficult things and are more receptive to my guidance.’

The public health nurses said that they use the ICDP when they teach and advise on what children need at various stages of their development. They also use the ICDP to make parents aware that their child is a separate individual who needs love and acknowledgement.

The public health nurses emphasised that the eighth guideline in the ICDP on positive boundary setting and regulation was useful for providing concrete alternatives to child-rearing violence. They believed that positive boundary setting can also reduce tiresome daily conflicts. ‘There can often be a lot of scolding about small things in a busy daily life. They find that there is less arguing when you praise the things that are good, which makes you want to do more of it.’

The public health nurses put emphasis on enhancing the parents’ perception of their own competence

A general finding was that giving acknowledgement to parents helps to enhance their perception of their own competence in interacting with their child. The public health nurses said that they advise the parents so that the parents themselves can find solutions that work for them. Several nurses emphasised that this guidance must be delivered in a ‘non-didactic manner’, and that instead they must ‘ponder it together with them’, while giving the parents advice and information at the same time.

The public health nurses explained that they focus on voicing what is good about the interaction and that it is important the parents feel that they are good parents: ‘I think it’s essential that parents feel competent so that they can be confident parents and not ambivalent in their child-rearing role. If they feel insecure, the children will be insecure. When we focus on the things they do well and praise them for it, I find that they do more of that.’

The public health nurses believed that the acknowledgement and guidance they give parents can help to bolster their confidence in their role as a parent:

‘Having competence is not enough. They must believe that they can use it properly, have faith in themselves.’

‘I hope in each consultation that they leave with a better feeling, a little more confident about what they are doing.’

The public health nurses focus on the parents’ ability to see and understand their child

The public health nurses explained how in the home visit one week after the birth they start sensitising the parents by raising their awareness of the importance of seeing things from the child’s perspective, getting them to describe and praise the child, and giving the child positive attention. One example of this is the importance of becoming familiar with the child’s temperament and personality from early on by following the child’s lead and interpreting the child’s signals.

The nurses said that they ‘make positive comments’ and describe how they see the parents expressing love to their child. All the participants were concerned about getting the parents to see the child, understand the child and his or her signals, and respond adequately to them.

The participants in the study believed that one way to promote positive interaction was for the parents to imagine what it is like to be the child and understand his or her behaviour in relation to the context the child is in. It was said that children need to become familiar with their feelings, and the nurses encourage the parents to describe those feelings for the child when the child is angry or sad, for example.

By doing this, the child can feel seen and understood, and consequently can settle down more quickly: ‘Some parents have a need for the child to stop crying immediately after getting a vaccine, for example. They have a smoothie, milk and dummy at the ready. I say in advance that it’s alright to let the child cry a little and get some confirmation that it actually did hurt a little before they give the child a dummy.’

The participants said that the ICDP guidelines helped the parents to understand what is behind the child’s behaviour, especially when the parents speak of the behaviour in negative terms: ‘When they say that their children are obstinate, I try to change the focus by pointing out that they are independent. After all, that’s what they should learn to become.’

The informants said that parents’ perception of the child is critical for the care they give. Seeing and acknowledging the child just as he or she is form the basis for interaction that promotes development. Some informants said that when parents express a negative view of their child, they can also sometimes see a negative pattern of interaction that may have unfortunate consequences for the child:

‘My main goal is to get them to understand what is happening inside the child. The perceptions you have of your child is the basis for how you interact with him or her. If you mainly see your child in a negative light, then your child has lost.’

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that the public health nurses give a rich description of the many ways that they can promote positive interaction between parents and children and that the ICDP methodology and guidelines are reflected in their general description of how they can promote positive interaction. In their experience, the ICDP is valuable and useful in their daily work, even when they do not use structured group meetings based on the eight guidelines.

The public health nurses said that they apply the knowledge and guidelines on interaction from the ICDP and that they have acquired a conceptual framework and a professional approach to the parents that is useful in consultations at the child health centre. The participants’ choice of words in the interviews also reflects concepts from the interaction guidelines and sensitising principles in the ICDP programme.

Systematic follow-up requires regular group meetings

The ICDP prioritises the parents’ own activity and reflection over instruction (8). In the conversations about consultations, the public health nurses show special interest in how the parents perceive their interaction with their child in daily life, and they encourage the parents to reflect on what they talk about. Both the parents’ perception of the child and acknowledgement of the parents’ competence in caregiving are key aspects of the nurses’ conversations with the parents.

These principles are fundamental in the ICDP and are implemented in the consultations. However, without regular group meetings, as the ICDP calls for, there is no systematic follow-up of the parents’ reflections on the eight guidelines for good quality interaction.

Although the goal of the study was not to compare the ICDP components used by the public health nurses in consultations with the full ICDP programme, it is interesting to consider the advantages and disadvantages of various work methods. There is less opportunity for individual activity and sharing of thoughts and experiences in consultations than in the eight weekly ICDP group meetings.

The public health nurses are in a position where they can begin a process of sensitising, raising awareness and providing guidance as early as the child’s first week of life. As such, they have a golden opportunity to help the parents develop a positive, secure pattern of interaction from the very start of the child’s life. They also have the opportunity to follow up in the twelve ordinary consultations at the child health centre in the child’s first two years of life.

In the national guidelines for child health centres and the school health services, the Norwegian Directorate of Health recommends that six of the ordinary consultations at the child health centre take place in groups (4), which also offers the opportunity for sensitising as parents share their experiences.

The public health nurses can reach out to more parents by integrating their ICDP knowledge into ordinary consultations at the child health centres. At the same time, they can probably not expect to see changes in the parents similar to that which occurs in a group intervention spread over several weeks. In group interventions, they test out and share experiences in practice, which has been shown to be important for achieving lasting change (14, 19).

The cognitive aspect is downplayed

The findings illustrate a characteristic of the ICDP, namely, ‘its focus on the caregiver’s perception (definition) of the child as crucial for the quality of the interaction that will follow’ (8, p. 21), which is also supported by experience internationally (13, 20). The ICDP appears to encourage the public health nurses to focus on exploring parents’ thoughts and feelings. The programme is a practical tool, too, as it may help to reduce advice and attempts to change behaviour that are not based on what the parents already think and do.

When the public health nurses reflect on which components of the ICDP they apply, they highlight the emotional and regulating components of the programme. They focus less on the pedagogical and cognitive components, such as putting experiences into words (8). It is possible that the nurses do not give priority to the cognitive aspect.

However, it is also possible that they actually use the cognitive aspect, but that they take it for granted, or that they thought the interviewer was interested primarily in the emotional and regulating aspects. The cognitive aspect has previously been shown to be essential for children’s development (21) and this would be interesting to study further, possibly following up with observational studies.

Reliability and limitations of the study

The findings of this study do not apply to public health nurses in general. The study is based on the participants’ reflections, not on observation, and gives no indication of what the public health nurses actually do or how the parents perceive their interaction with the nurses.

The lead author is a public health nurse and teaches in the ICDP. This may have helped to ensure that the questions were relevant and that there was an atmosphere of trust during the interviews, but may also have contributed to some components being overlooked or participants viewing the ICDP in an overly positive light. We tried to minimise the lead author’s impact by documenting her prior understanding throughout the entire research process.

The lead author provided information about her role as a researcher before the interview and examined statements that were not related to the ICDP. None of the comments suggested that the lead author was perceived as being an exponent of the ICDP. The effect could also have been the opposite if the participants thought that the interviewer wanted the ICDP to be used in keeping with the intention.

The reliability and interpretation may also have been affected by the lead author’s in-depth knowledge of the guidelines so that we overestimate the significance of the ICDP components in the data. The study’s reliability is enhanced, however, because we paid systematic attention to the lead author’s prior understanding and because the second author read all the interviews and looked for alternative interpretations and perspectives. Secondary analysis is a controversial practice, but is nonetheless used extensively and has resulted in greater transparency (22, 23).

The study’s contribution to the ICDP knowledge base

Despite the study’s limitations, it increases knowledge about the programme. The ICDP principles were used previously in an intervention study without applying the entire methodology (15, 24), and the findings are comparable in the sense that the informants thought that the guidelines were relevant and appeared to have positive results.

Our study cannot speak to whether public health nurses with an ICDP certification are better or less prepared than public health nurses without this training. Recent studies show that it can be beneficial to use established programmes rather than create news ones that are adapted to the context in question (25).

One of the strengths of the ICDP is cultural adaptation, since the programme is based on fundamental needs and universal activities. Another key aspect is the importance of activating existing patterns of caregiving.

Internationally there is a dire need for better measures that promote the development of the youngest children, especially measures that prevent violence. The World Bank (29) documents that such support should include the parents’ perceptions of their child and focus on emotional development, cognitive development and positive regulation. The ICDP is one of the programmes that addresses this challenge, and this study helps to expand its knowledge base.

Conclusion

The public health nurses who took part in this study said that the ICDP has been an integral part of their way of approaching parents and children in consultations at child health centres. The ICDP influences what they choose to focus on and how they provide guidance so that parents and their children interact in a positive manner.

The nurses said that the ICDP has given them confidence, which they believe is useful in their role as adviser even when they are unable to hold eight weekly group meetings at the child health centres as part of the programme. From this perspective, it appears that the ICDP facilitator training is valuable, even when it is not used as intended.

We wish to thank the public health nurses who took the time to share their experiences with us.

References

1. Smith L. Tilknytning og omsorg for barn under tre år når foreldre går fra hverandre. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening. 2010;47(9):804–11.

2. Hart S, Schwartz R. Fra interaksjon til relasjon: Tilknytning hos Winnicott, Bowlby, Stern, Schore og Fonagy. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2009.

3. Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, Andersen CT, DiGirolamo AM, Lu C, et al. Advancing early childhood development: from science to scale. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. The Lancet. 2017;389(10064):77–90.

4. Helsedirektoratet. Helsestasjons- og skolehelsetjenesten. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for det helsefremmende og forebyggende arbeidet i helsestasjon, skolehelsetjeneste og helsestasjon for ungdom. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2017. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/helsestasjons-og-skolehelsetjenesten(downloaded 29.03.2017).

5. Barlow J, Johnston I, Kendrick D, Polnay L, Stewart-Brown S. Individual and group-based parenting programmes for the treatment of physical child abuse and neglect: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005463.pub2.

6. Helle J, Boonstra JO, Broch KR, Rød BY, Vøllestad J. En god sirkel. Tidsskrift for Norsk psykologforening. 2017;54(6):546–57.

7. Britto PR, Ponguta LA, Reyes C, Karnati R. A systematic review of parenting programs for young children. New York: UNICEF; 2015.

8. Hundeide K. ICDP Programmet – et relasjonsorientert og empatibasert program rettet imot barns omsorgsgivere. Skolepsykologi. 2005;7:9–25.

9. Christie HJ, Doehlie E. Enhancing quality interaction between caregivers and children at risk: The International Child Development Programme (ICDP). Today's children are tomorrow’s parents. Journal of the National Network for Professionals in Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011;30:74–84.

10. Stern D. The interpersonal world of the infant. New York: Basic Books; 1985.

11. Trevarthen C. The foundations of intersubjectivity: Development of interpersonal and cooperative understanding in infants. In: Olson DR, ed. The social foundations of language and thought. New York og London: W.W. Norton & Company; 1980.

12. Klein P. Formidlet læring. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 1989.

13. Super C, Harkness S. The developmental niche: A conceptualization at the interface of child and culture. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1986;9(4).

14. Skar A-MS, von Tetzchner S, Clucas C, Sherr L. The long-term effectiveness of the International Child Development Programme (ICDP) implemented as a community-wide parenting programme. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2015;12(1):54–68.

15. Dybdahl R. Children and mothers in war: an outcome study of a psychosocial intervention program. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1214–30.

16. Sherr L, Skar A-MS, Clucas C, von Tetzchner S, Hundeide K. Evaluation of the International Child Development Programme (ICDP) as a community-wide parenting programme. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2014;11(1):1–17.

17. Westerlund A, Garvare R, Nyström ME, Eurenius E, Lindkvist M, Ivarsson A. Managing the initiation and early implementation of health promotion interventions: a study of a parental support programme in primary care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2017;31(1):128–38.

18. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. 3. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2011.

19. Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman JR, De Mello MC, Gertler PJ, Kapiriri L, et al. Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet. 2007;369(9557):229–42.

20. Verdensbanken. World development report 2015: mind, society, and behavior. Washington DC: Verdensbanken; 2015.

21. Rogoff B. The cultural nature of human development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

22. Heaton J. Reworking qualitative data. London, Thousand Oaks og New Delhi: SAGE Publications; 2004.

23. Bishop L, Kuula-Luumi A. Revisiting qualitative data reuse: A decade on. SAGE Open. 2017;7(1):1–15.

24. Dybdahl R. A psychosocial support programme for children and mothers in war. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;6(3):425–36.

25. Gardner F. Parenting interventions: How well do they transport from one country to another? Firenze: Innocenti UNICEF. 2017.

Comments