People with dementia may benefit from adapted cognitive behavioural therapy

People with early stage dementia can have different insights into their disease, and their motivation to participate in conversations with therapists can vary. A manual-based intervention can help find a relevant goal for the therapy based on the person’s circumstances.

Background: Studies show that psychotherapy can help maintain the level of functioning and quality of life of people with dementia.

Objectives: This case study is part of the KORDIAL study. The objective of this randomised controlled intervention study was to assess how an intervention impacted on subjects’ everyday lives and quality of life. Furthermore, we want to describe the interaction between the subjects and the therapist.

Method: The intervention was based on cognitive behavioural therapy where the focus was on meaningful activities aimed at modifying depression, memory aids and reminiscence. The intervention consisted of eleven weekly meetings. We recorded log notes for each meeting. The log notes were analysed according to the principles formulated in Graneheim and Lundman’s qualitative content analysis.

Results: One subject did not understand the purpose of the intervention and thus failed to benefit from the tools. The other was motivated to learn and found out what she could do to have a meaningful everyday life, which, among other things, made her feel less depressed.

Conclusions: Disease insight and motivation are factors that must be considered when choosing a therapeutic approach to people with early stage dementia. One of the subjects might have benefitted more from a different approach. For the other subject, the intervention had a positive impact on their everyday life and quality of life. The participation of family members seemed to be beneficial and supportive for the person with dementia.

In 2012, around 77 000 people were living with dementia in Norway, most of whom were over the age of 70 (1). The number of people affected is increasing and represents a global challenge. Estimates show that the number of people with dementia worldwide will reach 65.7 million by 2030, and the figure is expected to double every 20 years (2).

The most common symptom is memory loss, particularly in respect of recent information. Daily activities like shopping and paying bills are gradually affected (3). There is currently no curative medicinal treatment, and the anti-dementia medicines that are available only have symptomatic and temporary effects (4).

Results from a review article show that non-medicinal therapies can be realistic and viable treatment options for people with Alzheimer’s disease (5). Cognitive training and stimulation, practising daily tasks and carrying out meaningful activities improved the quality of life of the people with dementia as well as their families. By providing support for the families and increasing their knowledge it was possible to postpone the institutionalisation of the person with dementia (5).

Objectives of the study

A German multicentre study, CORDIAL (cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive-behavioral treatment for early dementia in Alzheimer disease), showed promising results for people with Alzheimer’s disease (6). The results showed that the interventions had an impact on depression, insight and quality of life.

The German CORDIAL study forms the basis for the Norwegian KORDIAL study; a manual-based, randomised controlled intervention study that includes 200 people living at home with early stage dementia and their families.

In connection with the KORDIAL study, we conducted a qualitative sub-study with two subjects and their families. The objective was to evaluate the impact of the manual-based intervention on the subjects’ everyday lives and quality of life. A further objective was to describe the interaction between the person with dementia, their family and the therapist.

Research questions in the study

Based on the objectives of our sub-study, we aimed to establish the following:

- How did the intervention impact on the subjects’ everyday lives and quality of life, and how was the interaction between them and the therapist?

Method

In line with the objectives and research questions of the study, we used a hermeneutical approach that is rooted in a qualitative research tradition aimed at gaining an understanding, and where the goal is to describe (7). We therefore chose the case study method, which is relevant where there is a desire to explain, describe and thoroughly examine a phenomenon (8).

Case studies can be descriptive, interpretive or evaluative, or they may include all three elements at the same time, as in our study. In the descriptive part, the subject’s perspective is prominent. The interpretive element is intended to illustrate, support, challenge and develop existing theory. The main focus in the evaluative part is the researcher’s evaluations, with theories as the starting point (9).

We supplemented the study by using two quantitative measuring instruments as part of the main study: the Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (10), which maps depressive symptoms, and the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (QOL-AD) (11), which evaluates quality of life. The measuring instruments were used both before and after the intervention in order to identify any changes.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

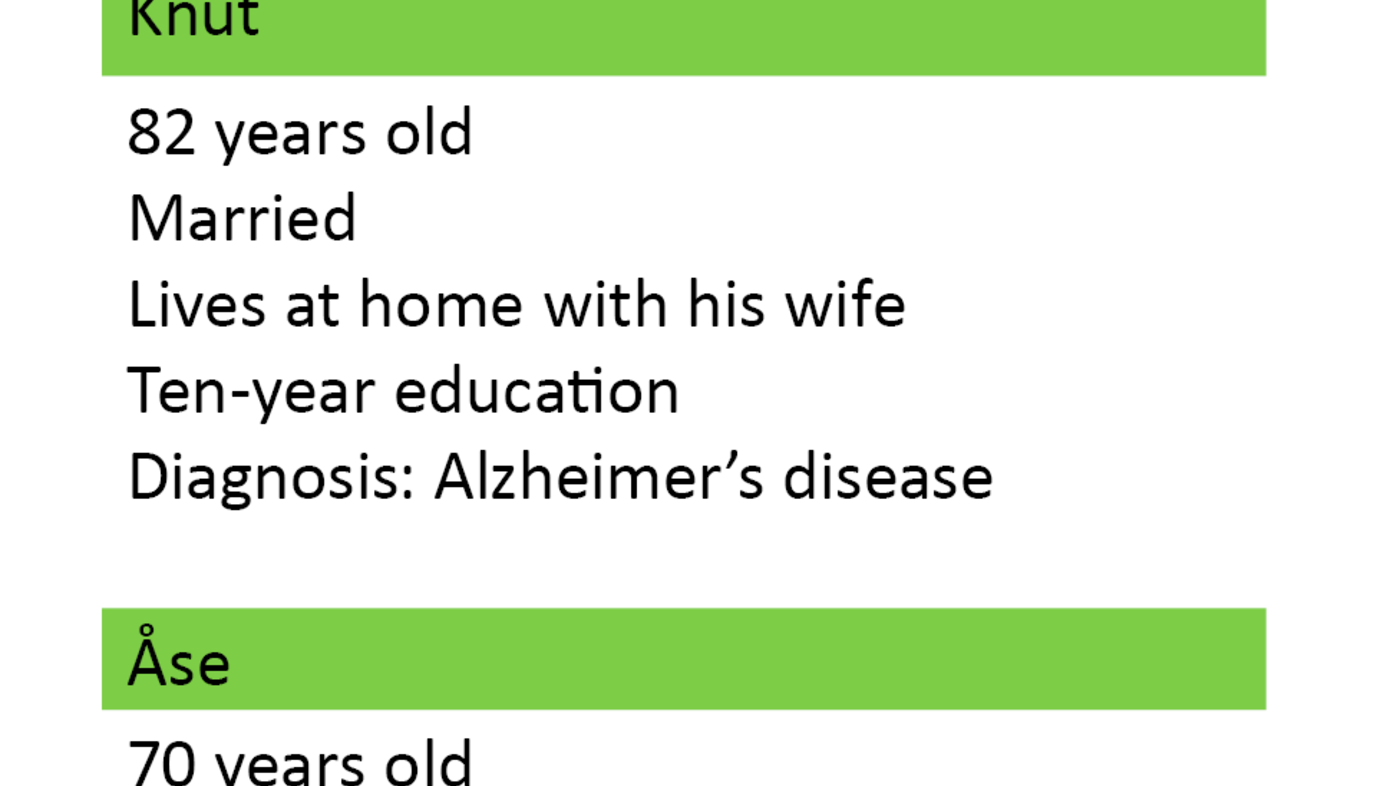

One of the criteria for inclusion in the study was an Alzheimer’s diagnosis within the last twelve months. Subjects also had to score at least 20–30 points on the cognitive test Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (12) and be living at home with a minimum of weekly contact with their family. Exclusion criteria were ongoing psychotherapy and serious somatic or mental illness as an additional diagnosis (Table 1).

Recruitment took place at a memory clinic at a university hospital in 2013. The memory clinic referred the subjects to a psychiatric clinic for the elderly in order for the intervention to be carried out there.

Description of the intervention

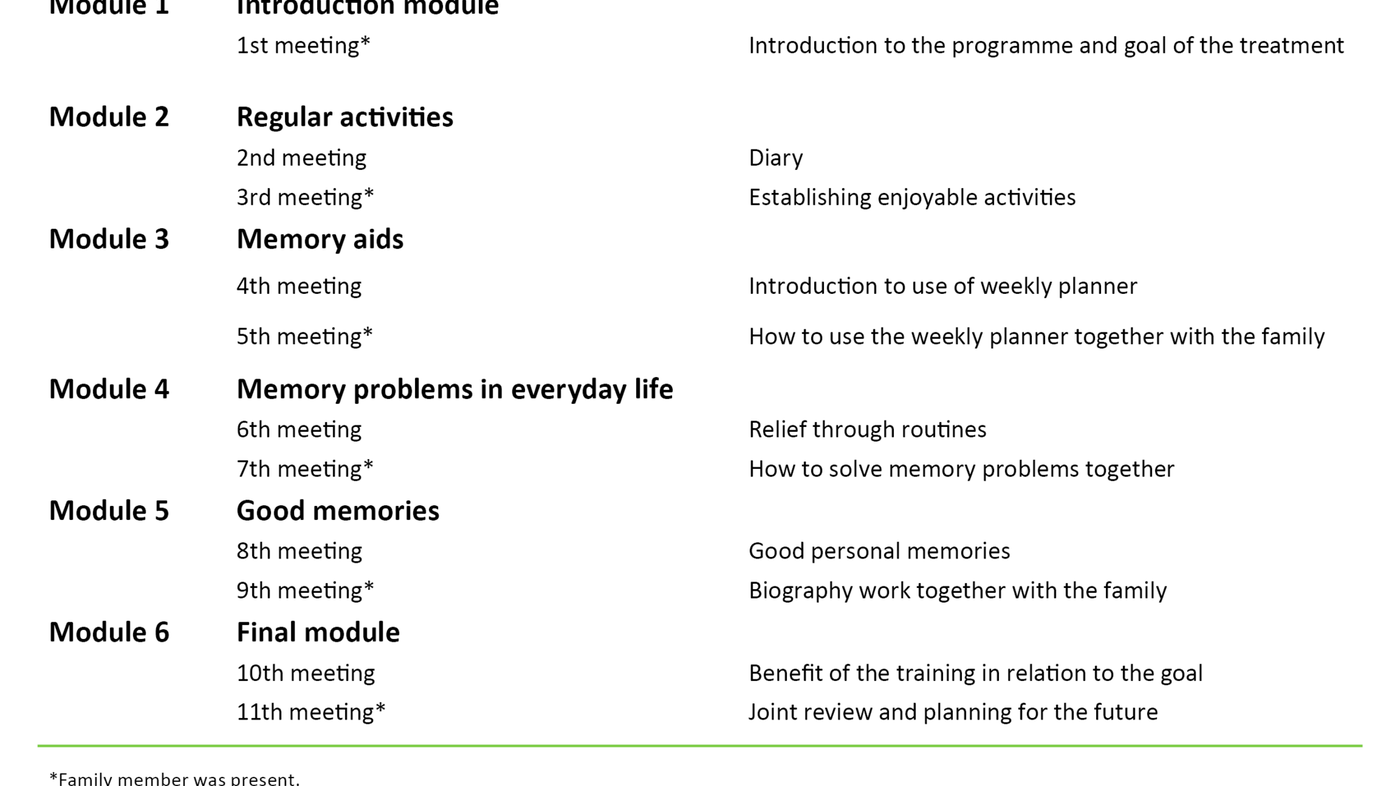

In the intervention, the therapist used a manual (13) containing topics for 11 weekly meetings (Table 2). The starting point was to find a relevant goal for the therapy based on the subject’s circumstances and everyday challenges. The manual also contained worksheets for use in meetings and at home. The therapist adapted the therapy to the subject’s level of functioning and needs.

A specialist mental health nurse with experience in cognitive therapy carried out the intervention. The objective of the intervention was to maintain the subject’s coping skills in everyday life and reduce depressive symptoms. The person with dementia recorded how daily activities affected their mood in a diary. This increased their awareness and enabled them to choose meaningful activities that had a positive impact on their mood.

One of the worksheets that was used as an aid was a list of enjoyable activities. In addition, the intervention involved the therapist using memory aids, such as a weekly planner, biography work and photo albums. Family members attended every second meeting in order to gain knowledge of and support the therapy. When the subject attended the meeting alone, he/she received a letter for their family outlining the topics they had covered.

Data collection

The therapist wrote journal notes and log notes after each meeting. The log notes constitute the bulk of the data in the study and indicate the topic of the meeting. They also provide a description of the interaction between the person with dementia, their family and the therapist. They also contain reactions and statements from the subjects and their families, as well as the therapist’s own observations and reflections. The log notes are made up of 31 typed pages.

Analysis

We analysed the log notes in accordance with Graneheim and Lundman’s content analysis method (14). The method consists of reading the text several times and identifying and condensing meaning units. It also includes an abstracting process in which subcategories, categories and topics are created. The analysis was conducted by the first author, who was also the therapist.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC) for the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority as part of the KORDIAL study. Subjects gave informed consent to participating and also consented to the material being used in the article. They received information about the right to withdraw during the study. Study subjects were anonymised.

Results

Case 1

Knut noticed that he had memory loss four to five years before the intervention. His short-term memory and learning and organisational abilities were very poor. He also needed help in areas such as getting dressed and cutting up his food.

Knut thought that he was managing well, but according to his wife, he was passive and preferred to sit in the chair and sleep. He was aware that his memory was impaired, but did not consider it a problem. Knut did not feel depressed and thought life was fine. His wife told me they had a daily programme; they went for walks, attended the senior citizens’ centre and went to the shops.

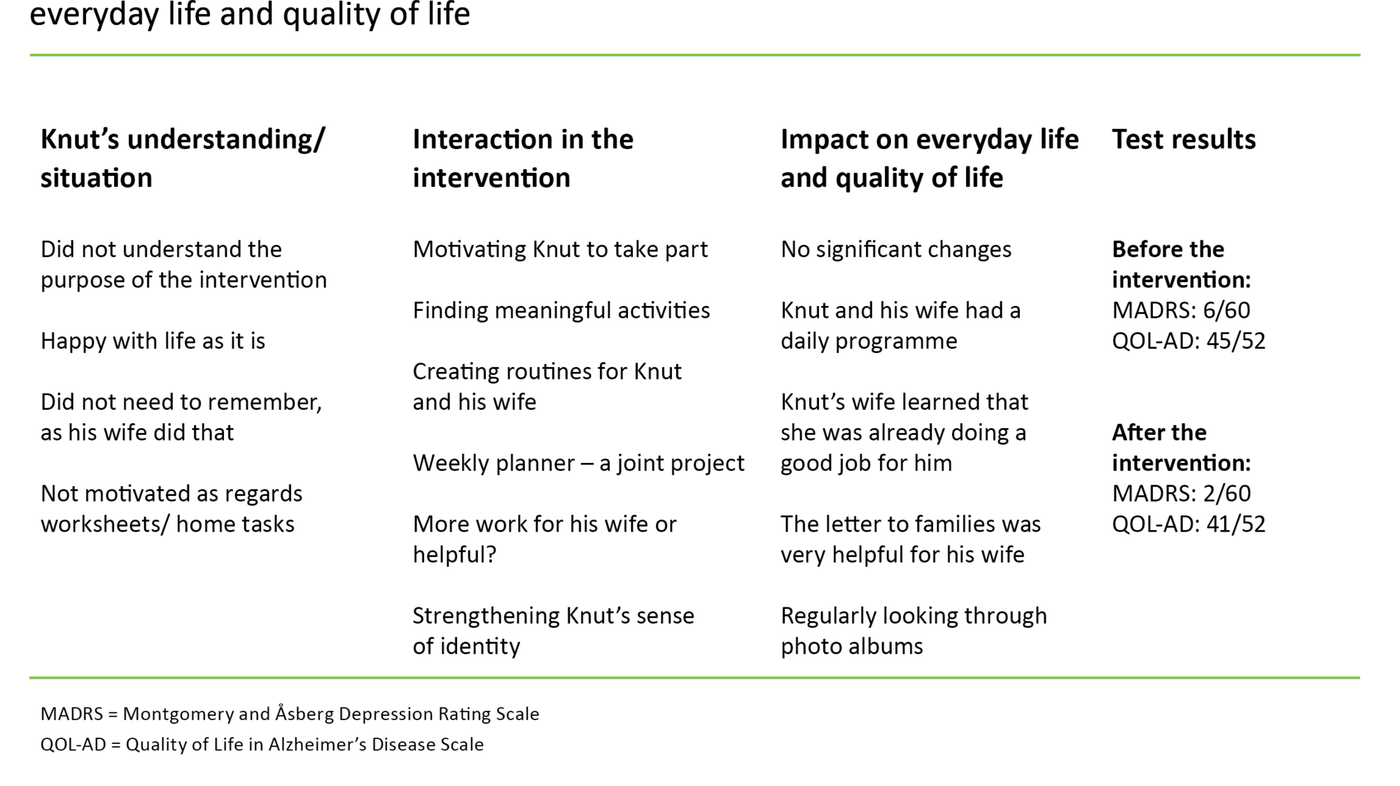

Impact on everyday life and quality of life

For Knut, the intervention did not lead to changes, and this is reflected in MADRS (10) and QOL-AD (11) (Table 3). His wife felt it was helpful to hear that she was already doing a lot of good for her husband and to find out that it was natural to get annoyed and feel fed up sometimes.

The interaction

Because Knut did not think that his memory loss was a problem, it was difficult to follow the manual on which the intervention was based. The therapist found it appropriate for Knut’s wife to participate in all of the meetings. The goal ‘to maintain the current level of functioning’ was something they formulated together.

Knut did not manage to record tasks in the diary aimed at raising his awareness of what he thought was meaningful. When the therapist talked about genealogy and drawing, which his wife said he had been interested in before, he showed neither interest in them nor wistfulness over the fact that they no longer gave him any pleasure. He said he was finished with these activities: ‘There’s a time for everything’. He also showed no interest in the worksheets. When the therapist asked if he would rather have no more meetings, he said, ‘On the contrary, this is really nice’.

Knut could not see the point of using a joint weekly planner, even though his wife thought it would be a good idea because he kept asking the same questions. He did not think he needed to use a planner because his wife ‘is so good at remembering’. When the therapist suggested making the planner an experiment and a joint project, he wanted to give it a try. By the end of the intervention, they had had some positive experiences with using the joint planner, but no new routine had been established.

They brought photo albums from Knut’s childhood to the meeting about good personal memories. They also frequently looked through albums at home, which evoked good memories and interest on Knut’s part.

Case 2

Åse’s memory started to deteriorate five to six years ago. She managed her everyday life well, was fond of housework and still cooked meals, but could easily lose track of time. She sometimes felt depressed, according to both herself and her husband, but was sociable and happy when with family and friends.

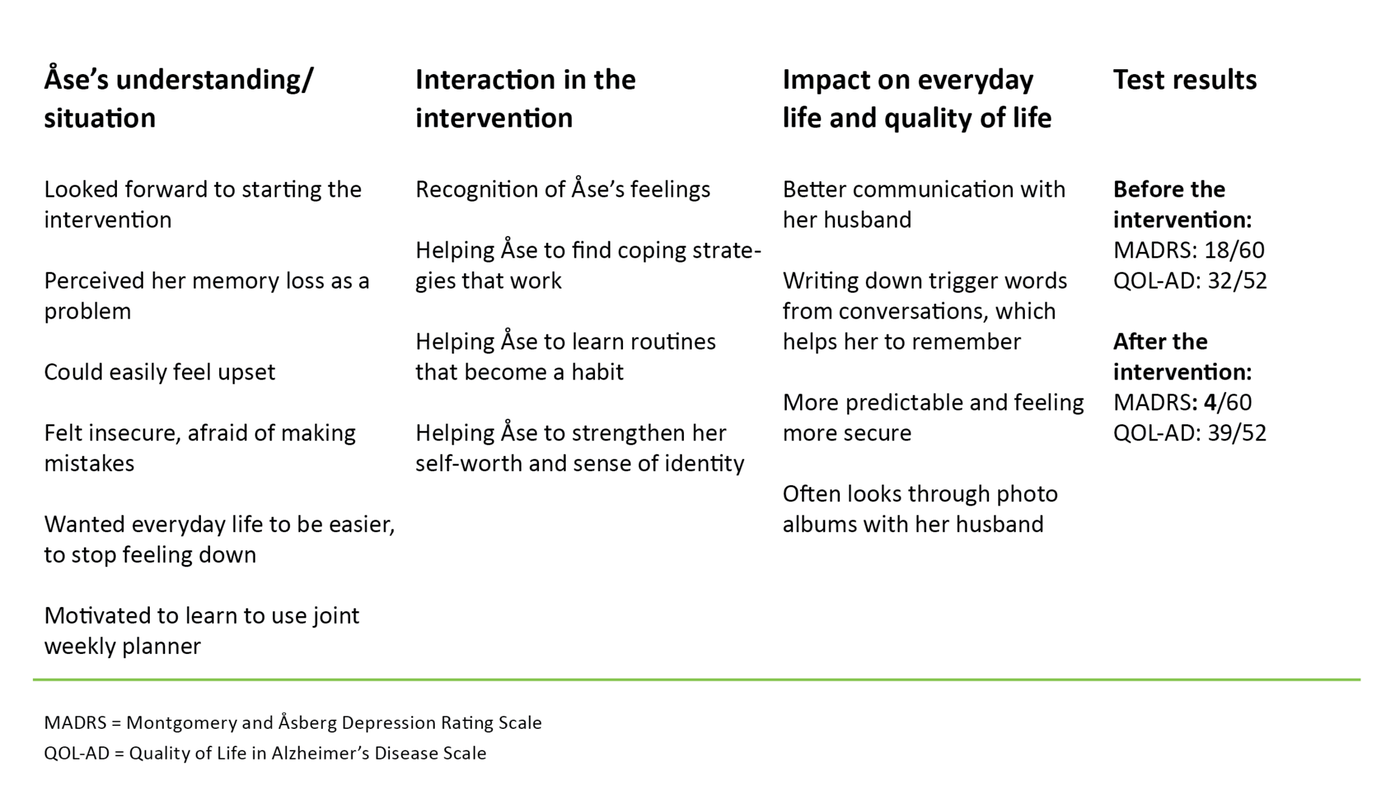

Impact on everyday life and quality of life

Åse believed that the intervention had a positive impact on her dark moods, as shown in MADRS (10), where her score descended from 18/60 to 4/60 during the intervention (Table 4). Quality of life, QOL-AD (11), went up slightly, which may indicate that the intervention had a positive impact.

Åse’s use of a joint weekly planner benefitted her considerably. Her communication with her husband improved, which led her to feeling more relaxed and not so afraid of making mistakes. Her husband said that the meetings were meaningful, and what they had learned was helping to make everyday life easier for them both.

The interaction

Åse was looking forward to getting started. She said at the beginning that her problem was memory loss and repeatedly asking the same questions. She formulated the following goal: ‘to have fewer mood swings and stop feeling down’. Her husband found it difficult when his wife did not remember anything from important conversations they had had recently.

Åse said that she felt stupid when she noticed that her husband became impatient or irritated. This was hurtful to both of them. She said that she sometimes needed more time and some trigger words from conversations from her husband. They explored this strategy together and found a better way of communicating.

Åse noticed that meaningful activities, such as light housework, had a positive impact on her mood. The home tasks that were part of the intervention made her aware of what she could do to improve her mood. She and her husband found a way to use a joint weekly planner. She was often a little depressed in the morning because she did not know how she was going to spend the day.

When they started writing in the weekly planner that she would do some laundry, ironing or watch a TV programme, she experienced predictability and thus security because, as she said, ‘I know what I’m going to do’. It was also important for her to write down what time her husband would come home and when she was to cook dinner.

They introduced routines for placing her keys, watch and handbag in designated places, which also made everyday life more predictable and made her calmer. Åse was able to remember a lot from the photographs they had used in the biography work, which made both her and her husband happy.

Discussion

The objective of our study was to evaluate the impact of manual-based intervention on the subjects’ everyday lives and quality of life. We also wanted to describe the interaction between the person with dementia, their family and the therapist.

Impact on everyday life and quality of life

The goal for Knut was ‘to maintain the current level of functioning’. The intervention had little impact on Knut’s everyday life and quality of life, which is consistent with the score in the MADRS and QOL-AD measuring instruments, where we saw little change. According to Knut, he felt that by being included in the study he was able to contribute.

Flexibility and adaptation of the manual with a view to meeting individual needs is crucial, and is in accordance with the descriptions by Tonga et al. (15). Knut’s wife felt that the letters to families contained useful information, and through participation in the intervention she learned that her efforts were helping Knut considerably.

Åse’s goal was ‘to have fewer mood swings and stop feeling down’. The goal led to a change in the way she communicated with her husband, which made her less afraid of making mistakes. She felt that he had begun to see her differently. In light of Antonovsky’s theory, this can be interpreted as Åse gaining a sense of understanding and management of the situation (16).

Understanding can lead to mastery, health and well-being, and hence a better quality of life, which is also indicated in Åse’s QOL-AD score. Her everyday life became more predictable through the introduction of a joint weekly planner. As a result, she was less depressed. This was reflected in her MADRS score, which showed a reduction in depressive symptoms.

According to the findings of an international study, established psychological models such as cognitive behavioural therapy can reduce depressive symptoms in people with dementia (17). The study concludes that psychological interventions have the potential to increase the subject’s sense of well-being. The pleasure of looking through photo albums was a new experience for Åse and her husband, and they wanted to do more of it.

The interaction

From the therapist’s perspective, the interaction with Knut was a challenge because he did not think that he had memory problems. Knut and his wife had very different perceptions of their everyday lives. Among other things, Knut claimed that he participated in housework and wrote down appointments, which was not true according to his wife.

Knut showed no interest in trying any of the measures suggested in the manual. He seemed passive and lacking initiative, which is a behavioural change that occurs frequently in early stage dementia (18). His behaviour can be understood as denial of the disease (19) as a way of concealing his fear of not mastering everyday life (20).

His behaviour may also be due to lack of insight into the disease, which often occurs in early stage dementia (3). In Knut’s case, a different type of treatment may have been more suitable, such as cognitive stimulation, which can reduce apathy in people with dementia (21).

The compensation phase

The positive picture that Knut presented of his situation could be an expression of what Engedal calls the compensation phase (3). The phase is partly characterised by memory loss and problems relating to events in the right time perspective, such as when Knut claimed that he still wrote appointments in the desk calendar.

The findings of an international study show that living with the disease is often presented as a positive story, with the people with dementia emphasising what they mastered and expressing that they were satisfied with life (22). We recognise this phenomenon in Knut, who, in addition to emphasising how well he was doing, spoke about things that he apparently still did; reading books, doing small jobs around the house and going for walks on his own. According to his wife, this was not the case.

Knut had what Næss (23) describes as a fundamental mood of enjoyment in that he was content with life. This joy was also reflected in his MADRS and QOL-AD scores.

Memory work evoked interest

Knut got annoyed with his wife when she tried to motivate him because he did not understand the purpose of either the worksheets or the attempts to introduce a joint weekly planner. His wife found the situation challenging until the therapist suggested calling these home tasks an experiment and a joint project. This also appealed to Knut, who was then willing to try.

The memory work evoked an interest in Knut whilst also giving the therapist an impression of the person Knut had been, the values he had held and how is life had unfolded. The memory work seemed to build Knut’s self-understanding and identity, and gave him positive experiences.

Looking through photo albums can help recall happy feelings from times gone by. It can also enhance self-esteem, which is described as recognising oneself again (24), and is consistent with Tranvåg et al. (25), who argue that highlighting the life stories and life projects of people with dementia also helps to promote their sense of dignity in everyday life. Families also play a role in the continuity of their sick relative’s life (26).

Feeling upset

The therapist thought the interaction with Åse was fruitful and believed that the intervention was right for her. She was eager and interested in learning how she could increase her independence and improve everyday life, including in relation to her husband. Åse was aware of her memory failure, which in some situations made her feel upset.

People with dementia are sensitive to signs of lack of acceptance and inadequacy (27). The need to be seen and respected is therefore important (28, 29). Åse devalued herself because her memory was poor. Such thoughts can increase the risk of depression (30).

Feeling useful

Both Knut and Åse experienced happiness in everyday life and had good relationships with their spouses, in line with Næss (23). Næss argues that quality of life is about love, commitment, self-respect and happiness. Both expressed that they felt useful: Knut by supporting his wife with his arm and carrying shopping bags, and Åse by ironing and doing housework.

Åse thought the meetings were exciting. She liked getting home tasks and thought it was satisfying to talk about what she had learned when she came to the next meeting. She thought the intervention was meaningful and was motivated to make an active contribution, which is at the core of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence theory (16).

Antonovsky argues that our power of resistance depends on how understandable, manageable and meaningful we consider life to be. This includes a motivational component, which motivates change (16).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

It is important that validity and credibility are an integral part of the research process, which entails all stages being transparent, open and carried out with conviction (7). A weakness of the study may be the dual role of therapist and researcher, since the study might be characterised by subjective observation. The subjectivity was moderated by the co-authors being involved in the reflections in the analysis process.

The fact that the researcher was also the therapist meant that she could observe the subjects’ body language, which gave an indication of how they experienced the meeting. The observations were subjective and may therefore be inaccurate. If the dialogue in the meetings had been recorded digitally and then transcribed, this may have enhanced the credibility of the study by giving different researchers access to everything that was said.

The study has just two subjects, with different degrees of cognitive impairment. This necessitated different approaches to the intervention and resulted in different levels of efficacy. Qualitative studies do not aim to generalise findings, rather they are intended to go into depth and describe what happened, which can be useful in terms of further developing the experiences from this study.

One strength of the study was that the qualitative method was supplemented with quantitative measuring instruments to evaluate whether the intervention impacted on the subjects’ everyday lives and quality of life. The findings cannot be generalised, but further research can be carried out to examine quality of life and signs of depressive symptoms following a similar intervention with a larger dataset.

In addition, future research can explore how the situation of family members is affected by participating in the intervention, and whether a positive change could help people with dementia to remain living at home for longer.

Conclusion

Findings from this study show that the intervention affected the everyday lives of subjects and their quality of life in different ways and to different degrees. The interaction between the subjects and the therapist varied considerably depending on the subject’s insight into the disease and their motivation to participate.

Knut’s life was not particularly affected by his lack of insight. Åse was motivated to learn and felt that everyday life became more predictable when she used aids. Discovering what had a positive effect on her mood and improving the communication with her husband made her feel less depressed. Both spouses felt that their efforts were appreciated and that they had gained a better understanding of how they could support their family member.

There is reason to believe that a thorough study of people with dementia may make it possible to determine whether this intervention is suitable. Further research should study the person more thoroughly before including them and investigate the significance of the number of meetings on the benefit different people gain from the therapy. The intervention can also be tested in group meetings, or in combination with individual meetings.

References

1. Helse - og omsorgsdepartementet. Demensplan 2020. Et mer demensvennlig samfunn. 2015.

2. Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers & Dementia 2013;9:63–75.

3. Engedal K. Alderspsykiatri i praksis: lærebok. 2. ed. Tønsberg: Forlaget Aldring og helse; 2008.

4. Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;25(21).

5. Olazaran J, Reisberg B, Clare L, Cruz I, Pena-Casanova J, del Ser T et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of efficacy. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 2010;30:161–78.

6. Kurz A, Thöne-Otto A, Cramer B, Egert S, Frölich L, Gertz H et al. CORDIAL: Cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive-behavioral treatment for early dementia in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associate Disorders 2012;26:246–52.

7. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. En innføring. 3. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2013.

8. Yin RK. Case study research. Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2014.

9. Postholm MB. Kvalitativ metode. En innføring med fokus på fenomenologi, etnografi og kasusstudier. 2. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2011.

10. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A New depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal & Psychiatry 1979;134:382–9.

11. Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: Patient and caregiver reports. Journal of Mental Health and Aging 1999;5:(1):21–33.

12. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal Psychiat Res 1975;12:189–98.

13. Ulstein I, Gordner V, Tonga J. Kordial studien. Manual for terapeuter. 2013.

14. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research:concepts, procedures an measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today 2004;24:105–12.

15. Tonga JB, Karlsøen BB, Arnevik EA, Werheid K, Korsnes MS, Ulstein ID. Challenges with manual-based multimodal psychotherapy for people with Alzheimer's disease: a case study. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias 2016;31(4):311–7.

16. Antonovsky, A. Helsens mysterium. Den salutogene modellen. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2012.

17. Orgeta V, Qasi A, Spector AE, Orrell M. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2015;207(4):293–8.

18. Engedal K, Haugen PK. Demens – Fakta og utfordringer. 5. ed. Tønsberg: Forlaget Aldring og helse; 2009.

19. Wetterberg P. Hukommelsesboken – Hvorfor vi husker godt og glemmer lett. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag; 2005.

20. Ostwald SK, DugglebyW, Hepburn KW. The stress og dementia: View from the innside. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias; 2002;17(5):303–12.

21. Verkaik R, van Weert J, Francke AL. The effects of psychosocial methods on depressed, aggressive and apathetic behaviors of people with dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry 2005;20(4):301–14.

22. Steeman E, Godderis J, Grypdonck M, De Bal N, De Casterlé BD. Living with dementia from the perspective of older people: Is it a positive story? Aging & Mental Health 2007;11(2):119–30.

23. Næss S. Livskvalitet som psykisk velvære. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening 2001;16(121):1940–4.

24. Fossland T, Thorsen K. Livshistorier i teori og praksis. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2010.

25. Tranvåg O, Petersen KA, Nåden D. Crucial dimensions constituting dignity experience in persons living with dementia. Dementia 2016;15(4): 578–95.

26. Drageset I, Normann K, Elstad I. Familie og kontinuitet: Pårørende forteller om livsløpet til personer med demenssykdom. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Helseforskning 2012;8(1):3–19.

27. Hummelvoll JK. Helt – ikke stykkevis og delt. 7. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2012.

28. Husband HJ. Diagnostic disclosure in dementia: An opportunity for intervention? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2000;15:544–7.

29. Bahro M, Silber E, Sunderland T. How do patients with Alzheimer's disease cope with their illness? – A clinical experience report. JAGS 1995;43:41–6.

30. Teri L. Behavioral treatment of depression in patients with dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 1994;8(3):66–74.

Comments