Nursing competence in the municipal health service: can professional development be accommodated?

Following the introduction of the Coordination Reform, nurses employed by the municipal health service have had to deal with a growing number of complex, patient-focused tasks. The need for professional development is considerable, but there is no overall strategy in place.

Background: The Coordination Reform has brought changes to the work responsibilities of nurses employed by the municipal health service, and the demands on their professional skills have grown accordingly. The volume of complex, patient-focused work has increased, and the working day of nurses has become busier; their need for professional development is thus considerable. This study forms part of a major quantitative study (NursComp) which entailed a survey by research team of the nursing competence available to the municipal health services in the county of Sogn og Fjordane.

Objective: The study seeks to describe how nurses employed by the municipal health service are working to develop their professional skills and competence, and what challenges these nurses encounter in the process.

Method: We took a qualitative approach and conducted two focus group interviews in two municipalities in the county of Sogn og Fjordane. The sample consisted of six nurses from Municipality 1 and eight from Municipality 2.

Results: The nurses refer to many influencing factors when they describe their efforts to keep professionally updated – including the community of practice with fellow nurses, pause for reflection, time constraints, financial factors and insufficient managerial input in terms of planning and facilitation.

Conclusion: Nurses have a duty to keep professionally updated in order to meet the requirements of the health service. They need to plan their working day with their supervisors in order to ensure that such professional development is easily accommodated. The supervisors have an important role to play in facilitating professional development.

Municipal health and care services have been the subject of comprehensive structural changes in recent years (1, 2). The Coordination Reform (1) has brought changes to the work responsibilities of nurses employed by the municipal health service, and the nurses report that more and increasingly complex patient-focused tasks have been assigned to them.

It is the intention that specific patient groups should have a greater share of their health care provided outside the specialist health service, among them patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, dementia, cancer, certain forms of mental health issues, and substance abuse. Consequently, nurses need to increase their competence levels with respect to the observation and examination of these patient groups to ensure that changing clinical presentations can be discovered at an early stage. Additionally, the reform introduces greater demands on the nurses’ interaction skills (1, 3–8).

Despite these challenges, our informants felt that their new nursing tasks were exciting, challenging and rewarding (3, 9, 10), yet there is uncertainty as to whether their professional competence levels have been sufficiently strengthened to enable them to handle the varied needs of patients.

An inquiry conducted by the Office of the Auditor General shows that following the introduction of the Coordination Reform, local authorities have failed to sufficiently boost the competence levels of their staff. Consequently, their recommendation is for the Ministry of Health and Care Services to ensure that planned initiatives adequately contribute to a strengthening of professional competencies (11). One such initiative is SkillsPromotion 2020, which is intended to ensure that service providers have adequate numbers of appropriately skilled staff to provide a professionally robust service (12). Other Scandinavian countries have also witnessed growing demands for professional competence and changes to the work responsibilities of nurses in the municipal health service (13, 14).

The concept of competence

Competence is a complex concept that is open to interpretation. It is generally considered to refer to skills required to carry out duties or tasks in a workplace setting (15–17). Such professional skills can be developed, are non-permanent and will depend on the context in which they are put into practice (16–18). There is a multi-faceted discussion surrounding the exact scope of competence, but professionals tend to express clear views when it comes to what or who they consider to be incompetent (16, 19, 20).

In order to assess the competence levels of nurses, we need to agree on what criteria to use, and how to verify their fulfilment (15). Nurses have a personal statutory obligation to carry out their work in a professional, ethical and lawful manner, irrespective of their workplace; the local authorities, as their employer, has an obligation to facilitate this (2, 21, 22).

Professional development on an individual level may involve the acquisition of knowledge, skills, attitudes and understanding, as well as the ability to tap into the competence of others, with a view to present and future duties as well as the organisation’s community of practice (23). Benner’s model of skills acquisition takes a relational view on learning and points out that nurses can develop from novice to expert by gaining knowledge that is formed not only within the individual, but in dialogue with other people in the practice community.

However, not everyone will reach the level of expert (24). For the individual’s skills acquisition to succeed, a number of factors must be present. The individual’s motivation, determination and personal qualities are important factors (17, 25–28), but additionally, the working environment must accommodate interaction between social and material contexts in order to enable staff to develop their own professional competence levels (26, 28–30).

The study objective

This article discusses a study that forms part of a larger work, Nursing Competence in Municipal Health Care Services – the NursComp Study 2014–2018. This examines the nursing competence available within the municipal health services of Sogn og Fjordane county.

The sub-study follows up a survey that was conducted in three of the county’s municipalities in 2013, utilising the Nurse Competence Scale (NCS) instrument (31). In the autumn of 2014, we conducted focus group interviews in two of the three municipalities involved, in order to deepen our understanding of the issues.

The study’s objective is to describe how nurses employed by the municipal health service are working to develop their professional skills and competence, and what challenges these nurses encounter in the process.

The study seeks answers to the following questions:

- How do the individual nurses feel about their daily work responsibilities?

- What factors are conducive or obstructive to the nurses’ efforts to develop their own professional skills and competence?

Methodology

The study was conducted in two municipalities on the west coast of Norway, each with a population in excess of 10 000. We adopted an explorative qualitative research design, which involved focus group interviews. A qualitative research method was chosen to allow us to describe and explore human experiences, perceptions and qualities. The qualitative methodology accommodates our desire to present the variety and nuances in the material (32, 33).

The inclusion criteria for nurses to take part in the study were employment by one of the local authorities that took part in the NCS survey, and that their workplace was either a nursing home or the community nursing service. We conducted one pilot interview prior to the focus group interviews. Testing the interview guide in this way is conducive to obtaining feedback on the questions included.

By summarising their conversation together with the participants at the end of the interview, the researchers are able to clarify any ambiguous details in the questioning, establish whether the questions are topical, and check that they fit in with the natural flow of the conversation (34). We revised five of our seven interview guide questions following the pilot interview. Data obtained through the pilot interview have not been included in the study because the participants did not fulfil the inclusion criteria.

The informants

We contacted the chief municipal executives and the relevant heads of department for the two local authorities involved, and obtained their permission to conduct the study. Informants were recruited by local ward managers employed by the municipality.

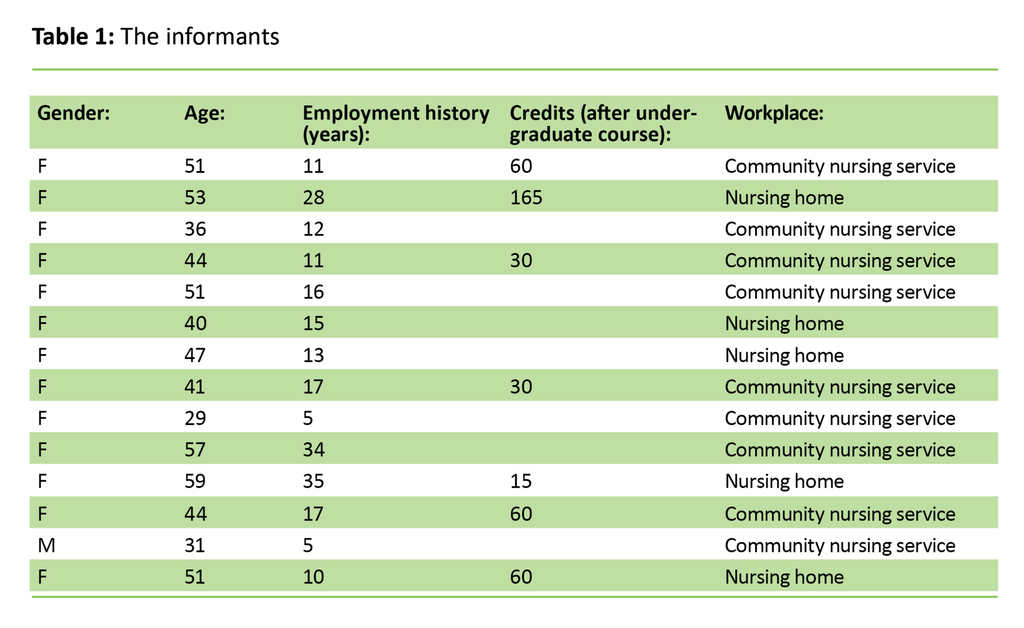

We recruited 14 nurses – one male and 13 female. There were six nurses allocated to Focus Group 1 and eight nurses to Focus Group 2. Nine of the nurses were working for the community health service, while five were working in nursing homes. The average age of the informants was 45.3 years, with a median of 45.5 years.

The length of their respective employment histories ranged from 5 to 35 years, with an average of 23 years and a median of 14 years. Eight nurses had specialty training. Table 1 provides an overview of the informants with details of their age, employment history and specialty training.

Data collection

We conducted the focus group interviews in meeting rooms at the nursing homes where some of the informants worked. The interviews lasted for a maximum of 1.5 hours. The first author acted as moderator, while the second author took the role of assistant. The moderator’s job was to introduce the interview topics and to facilitate a good exchange that would allow everyone to voice their opinions (32–34).

It is important for the moderator to believe that the informants hold interesting information and to be a sensitive listener who tries to understand the informants’ perspective (34). The assistant was tasked with recording the interviews on a digital sound recorder, noting down keywords and asking clarifying questions (33, 34).

We made use of an interview guide with seven open-ended questions based on the categories in the NCS questionnaire. The questions referred to the helping role, teaching/coaching, diagnostic functions, managing situations, therapeutic interventions, ensuring quality and the work role (31).

The informants received the interview guide prior to the focus group interview, to enable them to prepare. The informants were offered an opportunity to read the interview transcripts but declined the offer.

Analysis

We subjected our material to a qualitative content analysis. This method focuses on identifying similarities and differences in the studied text. The text’s manifest content is its specific narrative, often presented in categories. The themes that emerge from the content analysis are seen as expressions of the latent content, i.e. the implicit meaning of the text (35).

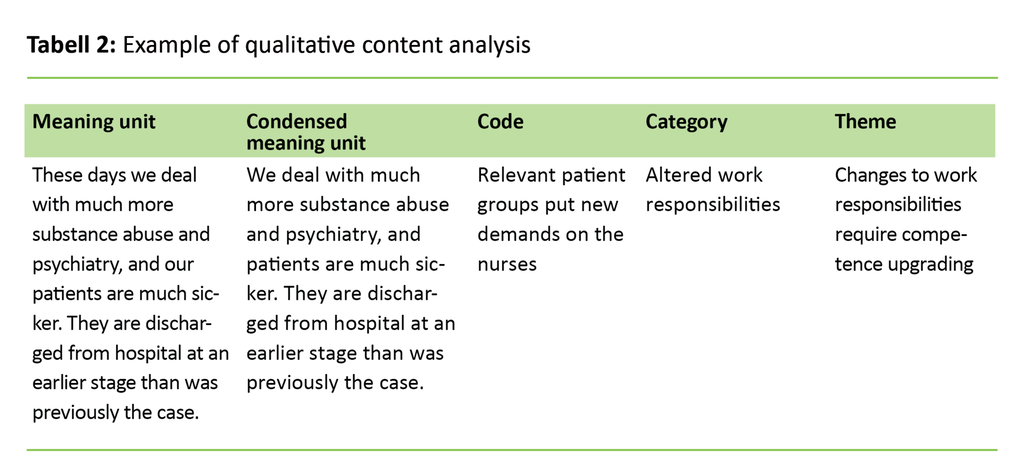

The analysis process started at the interview stage. Following the interviews, the moderator and assistant discussed potential conversation outcomes and made notes of these discussions. The first author proceeded to transcribe the material. After transcription, we read the transcripts multiple times and compared them with the sound recording to make sure that the content had been fully understood.

The moderator and the assistant reviewed the transcripts and wrote up summaries of the two interviews to facilitate the identification of any coinciding patterns. We also extracted quotes and studied these in depth in order to identify the meaning units. At the next stage of the process we condensed the meaning units without changing their content (35).

We proceeded to subject the meaning units to analysis and abstraction, but all the while it was important to maintain their original sense. On this basis, we allocated codes to the various units. These had not been predefined, but were generated in the course of our work with the data (32).

We then divided our material into categories before we eventually formulated its latent content which was split into three different themes. Table 2 shows an example of how we conducted the qualitative content analysis.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Data Protection Official at the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) as a sub-study under the NursComp project (project number 47191). The study was conducted and the data stored in compliance with research ethics guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki (36).

Well ahead of the interviews, the nurses were informed in writing of the study, its themes and objectives, methodology, data anonymisation and voluntary participation. This information was repeated verbally at the start of each focus group interview. The informants took part in the study on a voluntary basis, and they all signed a declaration of informed consent. The informants are anonymised throughout the text and cannot be identified in the material presented.

The results

Changes to work responsibilities require competence upgrading

The nurses consider their own role to be that of a common thread running through the service provision offered to patients. They carry out what they refer to as ‘standard nursing tasks’, which involves the planning and provision of nursing care, participation in cross-disciplinary work and cooperation and interaction with the patients’ families.

The informants have found that their work responsibilities have changed over time, particularly after the introduction of the Coordination Reform: ‘These days we deal with much more substance abuse and psychiatry, and our patients are much sicker. They are discharged from hospital at an earlier stage than was previously the case. And of course, that puts great demands on us’, said one of the informants.

The nurses describe an increased need to develop their own clinical competencies and to avail themselves of good mapping tools, to enable them to discover changes in the patients’ condition at an early stage. They find that such professional development is essential to enable them to report correctly to the duty doctor, who at times may be based miles away from the patient in question.

In nursing homes, the nurses also note differences with respect to more comprehensive patient rehabilitation initiatives, and they observe that individuals who suffer from dementia are hospitalised at a more acute phase of their disease. In this context they are looking to increase their knowledge and skills with respect to these specific patient groups. In relation to these changes, the informants report that they miss having time for reflection with their colleagues on professional issues and events: ‘I often miss having time to reflect. Just to sit ourselves down and think things through’.

Plans are rarely made for systematic professional development

The informants describe a complex and challenging working day, and they find it difficult to fit in any professional development. If professional challenges arise and they do not have the necessary knowledge to address them, they still need to resolve the matter on the spot. In this scenario, the informants access literature on the Internet, they discuss the matter with nursing colleagues and other health professionals, or they contact the specialist health service or a pharmacy for advice.

The nurses make use of the master–apprentice learning method on a daily basis in that experienced and knowledgeable nurses involve less experienced colleagues in learning situations. They feel that his practice works well, but they have to facilitate it themselves, except when they are involved with the induction training of new employees, which is part of a standard routine.

They need to read nursing journals in their spare time, for there is neither time nor space for it in the workplace. Staff who are meant to plan and implement training for their colleagues find that their supervisor fails to make the necessary arrangements: ‘Of course, we have made plans for first-aid training. And it’s been in the diary for a long time. You just come to a halt, and then you can’t afford the time because everyone else has such a lot to deal with – or there is such a lot of other things we all need to do.’

Most of the informants knew nothing of the municipal authorities’ professional development plan for their workplace. They talked about this lack of knowledge as a factor in their uncertainty about whether they might receive support for attending courses or signing up for specialty training, and this in turn led to lower motivation. One of the informants says: ‘Well, we receive all sorts of offers of courses and that sort of thing, but finding someone to cover for you would create a problem. So it is never sufficiently prioritised, no.’

Factors that are conducive or obstructive to professional development

The community of practice was highlighted as an important channel for acquiring new knowledge. According to the nurses, learning from one another is the most important source of professional development – whether this involves theoretical knowledge acquired through specialty training, courses and in-service training days, or whether it involves practical skills such as procedures or the use of technical medical equipment. One of the nurses says: ‘We make use of one another for what it’s worth.’

Self-motivation and a personal interest in the profession were also listed as factors conducive to professional development, as well as the need to be committed to the profession. Some informants talked about attending a weekly departmental staff meeting while on their lunch break, with the topic up for discussion frequently being of a professional nature. These staff meetings worked well, were planned for and were incorporated into staff routines. The doctors’ ward rounds and cross-disciplinary meetings were also listed as arenas conducive to professional development.

The nurses reported that staffing levels were low at times, and that their shifts were so busy that they have more than enough to do just tending to their daily duties. In this scenario, professional development is not a priority. Meanwhile, the informants also report that professional development efforts are largely up to themselves. Arrangements are rarely put in place in order to allow for professional updating or specialty training, and the management do not set any requirements for updating skills.

They also felt that there was no clear departmental plan for professional development that would give staff an insight into what competencies their employer wanted them to have. Furthermore, they pointed out that they miss a cross-disciplinary working environment where the topping up of professional competencies forms a part of the working day.

One of the factors that influence the professional development of nurses is a lack of finances in the local authorities: ‘When it comes to courses, there’s just no budget for it. I came from a sector that was a priority investment area – and the budget for attending courses was really generous; I was extremely shocked to discover this municipal poverty.’

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how nurses employed by the municipal health service are working to develop their professional skills and competencies, and how they tackle the challenges they encounter in the process.

It is well known that the municipal health service is in great need of competent staff. In order to meet this need, the nurses have to work on their professional development (21, 22). The individual’s motivation and personal qualities are important prerequisites for personal professional development (17, 25–28).

Learning from one another

The study’s informants clearly stated that the community of practice provided by their colleagues was important to their efforts of keeping professionally updated, for instance by learning practical procedures from one another and by providing an opportunity for reflection. A community of practice can serve as an arena for individuals to exchange opinions about work responsibilities and professional issues.

This interaction brings learning with respect to how the nurses may develop and improve their skills. According to social learning theory, a community of practice will bring about learning, even if to external eyes it may look like an ad hoc solution designed to make the working day run smoothly (37). It is warranted to question whether this theoretical stance on passing on knowledge is sufficient in the face of demands for new competencies in the workplace (17).

Easier to identify incompetence than competence

Evidence-based learning through interaction with patients and their families plays an important role in the nurses’ efforts to raise their level of competence (38), but inadequate specification of what skills are needed makes it difficult to decide what training paths to choose (15).

The informants pointed out that when they find themselves in new and unfamiliar situations, they are quick to look for information from their colleagues, literature, the specialist health service or by contacting experts in the field. The same has been demonstrated by earlier studies (8, 38, 39). Consequently, it appears that incompetence is easier to identify than competence, and that this raises the nurses’ awareness in terms of professional development.

This way of driving the work may serve to conceal the raised competence levels to managers, so that nurses individually respond to the needs that arise from changing tasks and responsibilities (39). This development will not be conducive to learning on an organisational level (40).

Insufficient time and inadequate strategies

Time constraints at work, and challenges associated with the municipal resource situation and staffing levels, are familiar problems (5, 41). In a pressurised work situation, the nurses find it difficult to set aside time for professional development, even if the organisational framework is safe and provisions are appropriately made (8, 41).

The informants feel that there is no overall strategy for professional development. Earlier studies have shown the same (8, 39, 41). Nurses with specialty training or other forms of expertise consider their own competencies to be relevant and important for their personal professional development and for their workplace community, but find that their skills are not always put to use.

Employers may not be aware of the skills of their nurses, and staff representatives are never present when the matter of professional development is up for discussion. The officer who heads the municipal health service is responsible for ensuring that the appropriate competencies are available and for facilitating opportunities for employees to acquire these competencies (2).

Nevertheless, it is important to point out that the nurses generally report to have found the changes to their work responsibilities to be interesting and challenging; this has been similarly demonstrated by a number of studies in recent years (3, 8–10). Mid-career changes may make working for the municipal health service a more attractive proposition, and this will be an important factor in the future when more staff and skills will be required to care for patients (8, 11).

The nurses feel that in many areas they have the required competencies, but that due to the way the service is organised, their skills are not put to use where they are needed (5, 8). The results show that competencies relating to substance abuse, mental health and complex disorders are in demand among nurses. Nurses have only limited earlier experience of these areas of practice because they have never been prioritised by the municipal health service.

The study’s weaknesses

Only a limited number of informants took part in the study, and they were all recruited from a restricted geographic area. Population numbers are relatively low in both municipalities represented in the study. It is not possible to generalise on the basis of this qualitative study, and the results may well have been different if the study had been carried out in different municipalities.

Nevertheless, it is our opinion that the findings are consistent with the findings of earlier studies, and that a repeat of the study in different municipalities would probably generate similar results.

Conclusion

Nurses have a duty to keep professionally updated in order to meet the demands of the health service, but nurses cannot achieve this on their own. Our findings show that nurses frequently acquire new knowledge by turning to unplanned activities such as learning within the community of practice, looking up nursing issues on the Internet and contacting specialists in the field to discuss a patient’s case. They need the assistance of their management if they are to plan their work and organise their services so that professional development becomes a natural part of their working day. It appears that this is not the case today.

Furthermore, local authorities need to put in place a strategy for the professional mapping and development of their nurses. Despite the problems, the nurses consider their working day to be challenging and exciting, and they enjoy their new responsibilities. Enjoyment may well lead to greater job satisfaction and enhanced motivation to stay in their jobs.

This study’s findings suggest it would be pertinent to conduct further research into what measures are conducive to professional development in the municipal health service. Professional development will constitute a challenge for our educational institutions in the years ahead, both in terms of safeguarding basic nursing competencies and in terms of customising postgraduate courses and master’s degree programmes so that they meet the challenges of the municipal health service.

References

1. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. St.meld. nr. 47 (2008–2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid. 2009.

2. Lov 24. juni 2011 nr. 30 om kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester m.m. (helse- og omsorgstjenesteloven), (2011). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2011-06-24-30(downloaded 21.02.2017).

3. Bing-Jonsson PC, Bjørk IT, Hofoss D, Kirkevold M, Foss C. Competence in advanced older people nursing: development of ‘Nursing older people – Competence evaluation tool’. International Journal of Older People Nursing 2015;10(1):59–72.

4. Bing-Jonsson PC, Hofoss D, Kirkevold M, Bjørk IT, Foss C. Sufficient competence in community elderly care? Results from a competence measurement of nursing staff. BMC Nursing 2016;15(5):1–11.

5. Norheim KH, Thoresen L. Sykepleiekompetanse i hjemmesykepleien – på rett sted til rett tid? Sykepleien Forskning 2015;10(1):14–22. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2015/02/sykepleiekompetanse-i-hjemmesykepleien-pa-rett-sted-til-rett-tid(downloaded 13.11.2017).

6. Tyrholm BV, Kvangarsnes M, Bergem R. Mellomlederes vurdering av kompetansebehov i sykepleie etter samhandlingsreformen. In: Kvangarsnes M, Håvold JI, Helgesen Ø (eds). Innovasjon og entreprenørskap. Fjordantologien 2015. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2016 (p. 174–87).

7. Opsahl G, Solvoll B-A, Granum V. Forførende samhandlingsreform. Sykepleien 2012;100(3):60–63. Available at: https://sykepleien.no/forskning/2012/02/forforende-samhandlingsreform(downloaded 13.11.2017).

8. Hovland G, Kyrkjebø D, Råholm M-B. Sjukepleiaren si kompetanseutvikling i kommunehelsetenesta – samspel mellom utdanningsinstitusjon og arbeidsplass. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning 2015;11(1):4–19.

9. Gautun H, Syse A. Samhandlingsreformen. Hvordan tar de kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenestene i mot det økte antallet pasienter som skrives ut fra sykehusene? NOVA-rapport 8/13. Oslo: Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring; 2013.

10. Gautun H, Hermansen Å. Eldreomsorg under press. Kommunenes helse- og omsorgstilbud til eldre. Fafo-rapport 2011:12. Oslo: Fafo; 2011.

11. Riksrevisjonen. Dokument 3:5 (2015–2016). Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av ressursutnyttelse og kvalitet i helsetjenesten etter innføringen av samhandlingsreformen. 2016.

12. Heskestad S, Korsvold L, Solsvik A, Tønnessen CN. Kompetanseløft 2020. Oppgåver og tiltak for budsjettåret 2017. IS-2560. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2017.

13. Josefsson K, Sonde L, Wahlin T-BR. Competence development of registered nurses in municipal elderly care in Sweden: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2008;45(3):428–41.

14. Dansk Sygeplejeråd. Fremtidens hjemmesygepleje. Udfordringsrapport. København: 2011.

15. Eraut M. Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Falmer Press; 1994.

16. Garside JR, Nhemachena JZZ. A concept analysis of competence and its transition in nursing. Nurse Education Today 2013;33:541–5.

17. Eraut M. Transfer of knowledge between education and workplace settings. I: Rainbird H, Fuller A, Munro A. (red). Workplace Learning in Context. London: Routledge; 2004.

18. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and Assessing Professional Competence. JAMA 2002;287(2):226–35.

19. Eraut M. Concepts of competence. Journal of Interprofessional Care 1998;12:127–39.

20. Watson R. Clinical competence: Starship enterprise or straitjacket? Nurse Education Today 2002;22:476–80.

21. Lov av 2. juli 1999 nr. 64 om helsepersonell m.v. (helsepersonelloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64(downloaded 10.01.2017).

22. Norsk Sykepleierforbund. Yrkesetiske retningslinjer for sykepleiere. ICNs etiske regler. 2011.

23. Dalin Å. Veier til den lærende organisasjon. Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk; 1999.

24. Benner P, Have G. Fra novise til ekspert. Dyktighet og styrke i klinisk sykepleiepraksis. Oslo: TANO og Munksgaard; 1995.

25. Illeris K. Transformative Learning and Identity. Journal of Transformative Education 2014;12(2):148–63.

26. Khomeiran RT, Yekta ZP, Kiger AM, Ahmadi F. Professional competence: factors described by nurses as influencing their development. International Nursing Review 2006;53(1):66–72.

27. From I, Nordström G, Wilde‐Larsson B, Johansson I. Caregivers in older peoples' care: perception of quality of care, working conditions, competence and personal health. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 2013;27(3):704–14.

28. Lima S, Jordan HL, Kinney S, Hamilton B, Newall F. Empirical evolution of a framework that supports the development of nursing competence. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2016;72(4):889–99.

29. Valen K, Ytrehus S, Grov EK. Tilnærminger anvendt i nettverksgrupper for kompetanseutvikling i det palliative fagfeltet. Vård i Norden 2011;31(4):4–9.

30. Takase M. The relationship between the levels of nurses’ competence and the length of their clinical experience: a tentative model for nursing competence development. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2013;22(9–10):1400–10.

31. Meretoja R, Isoaho H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurse Competence Scale: development and psychometric testing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2004;47(2):124–33.

32. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervjuet. 2. ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2009.

33. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. 3. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2011.

34. Krueger RA, Casey M-A. Focus groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4 ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2009.

35. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 2004;24(2):105–12.

36. Helsinkideklarasjonen. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects 2013. Available at: http://legeforeningen.no/PageFiles/175539/Declaration%20of%20Helsinki-English.pdf(downloaded 21.02.2017).

37. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

38. Hynne AB, Kvangarsnes M. Læring og kompetanseutvikling i kommunehelsetenesta – ein intervjustudie av kreftsjukepleiarar. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning 2014;10(2):76–90.

39. Killie PA, Debesay J. Sykepleieres erfaringer med samhandlingsreformen ved korttidsavdelinger på sykehjem. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning 2016;12(2).

40. Senge P. Den femte disiplin. Kunsten å utvikle den lærende organisasjon. 2 ed. Oslo: Egmont Hjemmet; 1999.

41. Brenden TK, Storheil AJ, Grov EK, Ytrehus S. Kompetanseutvikling i sykehjem, ansattes perspektiv. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning 2011;7(1):61–75.

Comments