Women’s mental health after an induced abortion – a scoping review

Most of the women with mental health challenges after an induced abortion had had similar challenges before the pregnancy.

Background: A total of 11,081 induced abortions (IAs) were performed in Norway in 2020. In recent years, there has been a growing focus on women’s sexual and reproductive health. Nevertheless, there is little research on women’s emotional health after an IA, or on whether abortion puts a major strain on women’s mental health.

Objective: The objective of the study was to summarise knowledge on women’s experiences with IA and subsequent mental health problems in countries where abortion laws are similar to those of Norway.

Method: We used the scoping review method, and research articles were retrieved from CINAHL, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. Peer-reviewed articles from the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden and Norway published between 1 January 2011 and 25 February 2020 were included. The search identified 1156 articles, 13 of which matched the inclusion criteria and were included. The coding of the texts was inspired by Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis.

Results: The scoping review found little evidence to suggest that women experience mental health challenges as a result of an IA. It shows that it was the experiences and life events before pregnancy that had the greatest impact on women’s mental health after an IA. Being subjected to psychological or physical violence at any point in their life were particularly prominent factors. The findings indicate that women with a pre-pregnancy psychiatric history have a higher risk of experiencing mental health challenges after an abortion.

Conclusion: The study shows the importance of being aware that external factors such as unemployment may have an impact on women’s mental health after an IA. Most women who experienced mental health challenges after an IA already had challenges before pregnancy. It may therefore be appropriate to pay particular attention to how women with a psychiatric history deal with abortion. This would enable healthcare personnel to initiate relevant health care at an early stage.

Introduction

In the late 1970s and 1980s, abortion laws were liberalised in Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands and Finland (1, 2). This means that women are free to contact various agencies to arrange an abortion at a hospital before the end of the 12th and 24th week of gestation, depending on which country they live in (3–5). Abortions are free for all residents of the country in question (3, 5–6), except in Finland, where a standard fee is charged for the consultation (7).

Norway has the highest incidence of IAs in the world. In 2020, a total of 11,081 women underwent an abortion in Norway (8). The number of IAs has been declining since 2008. Since the abortion register was established in 1967, the number of abortions among women aged 15–29 is now at a record low (9). The conditions for undergoing an abortion in Norway are regulated through the Abortion Act (10).

The first systematic literature review of psychiatric sequelae of abortion was published in 1966 by Simon and Senturia (11). They found that studies from the United States and Europe were not comparable because of the major differences in legislation and the higher quality of the studies from Europe. In subsequently published research, IA was associated with an increased incidence of post-abortion mental health problems, but few cases were directly attributable to IA (12). However, mental disorders were also shown to be significantly reduced after the women had an IA (13).

A typical finding in much of the international research is that women with mental disorders prior to pregnancy also experience mental disorders after having an abortion (14–19). Many of the women who considered having an abortion were worried about what others would think (20), and about parents and partners wanting to influence their decision (21, 22).

The pregnancy was described as a crisis for the women (13), in which they felt both shame and relief after having an abortion (22, 23). In this decision-making process, the women who considered having an abortion would have preferred greater visibility of healthcare personnel (24).

A literature search from 2020 only identified one systematic literature review on IA in Scandinavia, which was based on qualitative research (22). In our scoping review, we wanted to also include quantitative research in order to substantiate or bring out new points of view on the existing research, as recommended by Petersen et al. (22)

The inclusion of quantitative research is important for being able to convey verified information about how women are affected by IA in Sweden, the Netherlands, Finland, Norway and other countries with similar abortion laws.

This is particularly relevant given the United Nations’ launching of a new Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) in 2015, which has strengthened the focus on women’s sexual and reproductive health. SDG 5 is dedicated to gender equality and strengthening the position of girls and women in society. This includes Target 5.6: to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights (25).

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to summarise knowledge on women’s experiences with IA and subsequent mental health problems in countries where abortion laws are similar to those of Norway. We wanted to raise awareness of IA and generate new knowledge on the relationship between IA and mental health challenges.

Method

We performed a scoping review based on the framework by Arksey and O'Malley (26). The purpose of a scoping review is to identify and summarise available data on a topic. The method focuses on the breadth within the topic, where the main findings are presented in a descriptive format that can include different study designs and methods (26).

Existing literature is used to draw conclusions about the overall situation. The research is thus summarised and can be further disseminated. We used the PRISMA-ScR checklist, which clearly sets out the reporting steps of the study. We did not apply for approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data or the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics as the study does not involve direct contact with informants, biological material (29) or personal details (30).

Literature searches

We performed systematic searches in databases, manual searches and a review of the reference lists in key articles (26). The databases CINAHL, MEDLINE via the Norwegian Electronic Health Library and PsycINFO were used. The search took place on 25 February 2020.

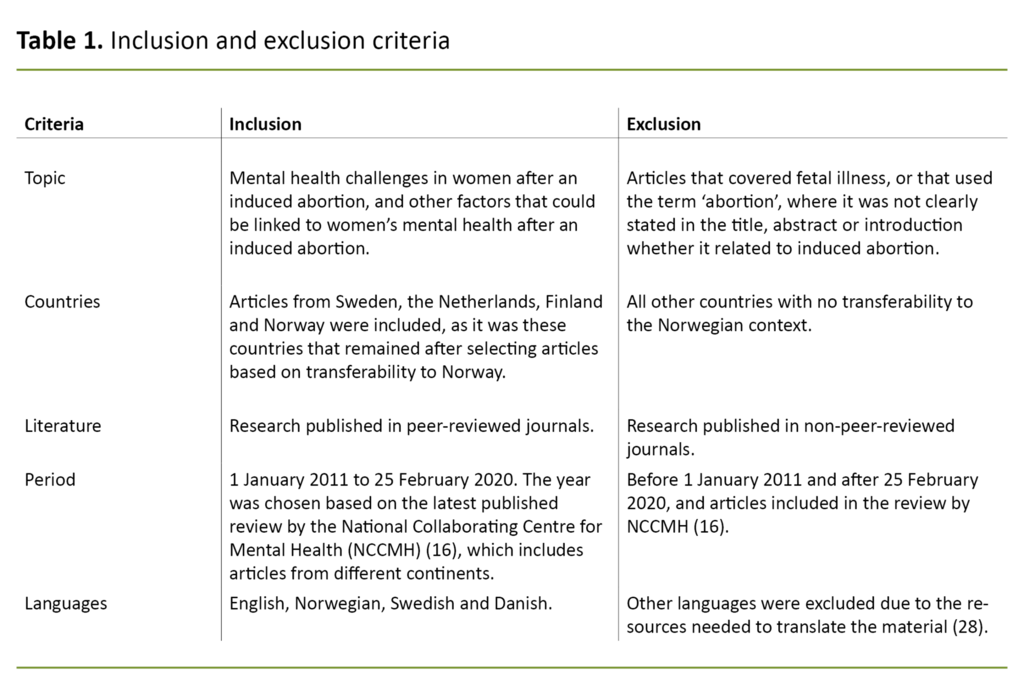

The search terms used were (Abortion, induced) OR (Induced abortion) AND (Decision-making) OR (Self-concept) OR (Personal satisfaction, life satisfaction) OR (Mental health). Search terms such as ‘Abortion induced’, ‘Decision-making’ and ‘Mental health’ were categorised as keywords and used both in Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH) and free text in order to include recently published research that had not been allocated a MeSH term from the databases. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Table 1.

The selection process

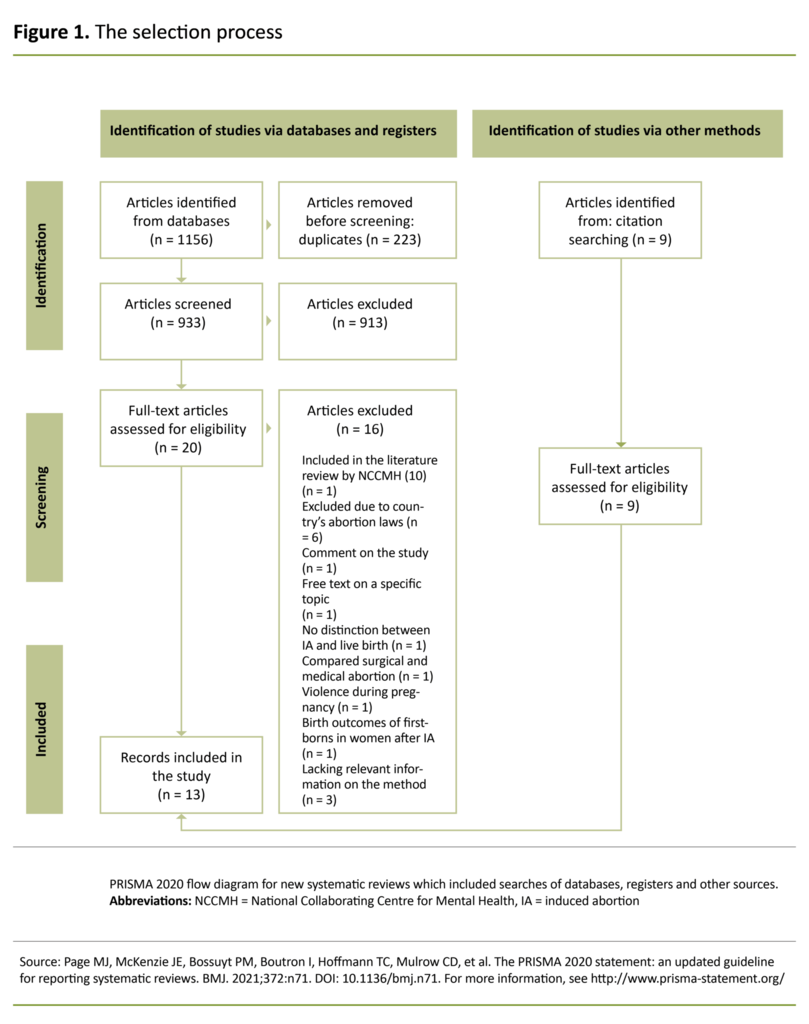

We excluded articles by reading titles, abstracts and full text in accordance with Arksey and O'Malley’s (26) strategy. After duplicates were removed, the selection began with the help of the reference management software EndNote. We then deselected articles where the abstract did not match the topic of the study.

This resulted in 29 remaining articles being read in their entirety, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 13 articles were included. The most common reasons for exclusion were unsuitable format and content for the topic of the study. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process.

Analysis

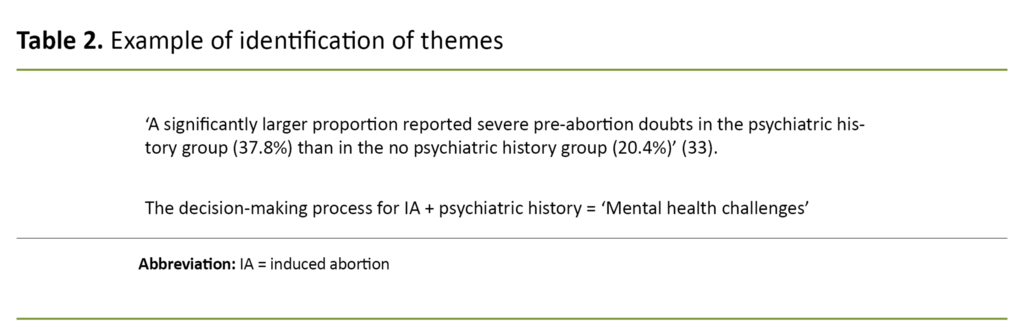

Arksey and O’Malley (26) recommend using an analytical framework or a thematic structure to analyse the data. We carried out a thematic analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke (31). The purpose of this analysis was to identify, map, describe and analyse the findings. When developing themes, we read the articles thoroughly, which led to us identifying 12 relevant themes. We then compared results and ended up with three main themes.

The themes were then further adjusted to align with the research question, resulting in three main themes, two of which had sub-themes: 1) Mental health challenges: Anxiety, quality of life, the decision-making process surrounding IA and mental health diagnoses, 2) Social challenges: Traumatic experiences and substance use, and 3) The role of the family.

Each theme was summarised with extracts from the relevant articles to ensure that relevant findings were not omitted. The excerpts were then viewed in context and rewritten as complete results. An example of how the themes were identified is given in Table 2, and is in accordance with Aveyard’s model (28).

Results

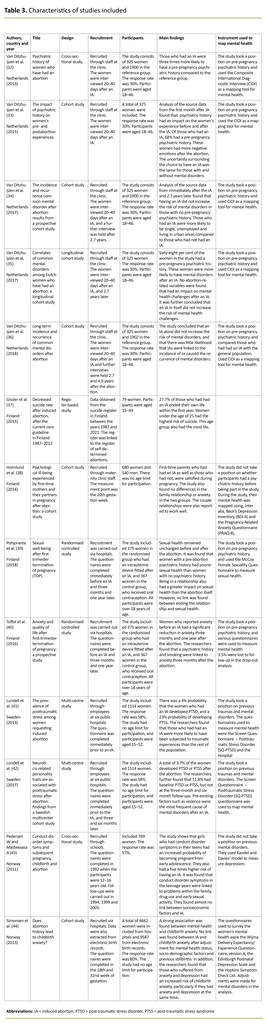

After the articles had been considered in relation to Norwegian abortion laws (10) and the inclusion criteria, we included 13 articles. Of these, five were from the Netherlands (32–36), four were from Finland (37–40), two were from Sweden (41, 42) and two were from Norway (43, 44). The included articles illuminated different perspectives of the research question and all had a different quantitative design. Several of the articles were from the same studies.

The five articles from the Netherlands were part of the Dutch Abortion and Mental Health Study (DAMHS), which was a cohort study with three measurement time points. The articles cover a variety of angles of the study topic and use different comparison groups to explore mental health challenges in women who have an IA (32–36).

Two of the articles from Finland reported secondary findings from a study on early provision of contraception after an IA. These findings were relevant for gaining a broader understanding of the women’s reactions after an IA (39–40). The two Swedish articles were from the same cohort study aimed at women who had an IA at six public hospitals in Sweden (41, 42). Table 3 presents the articles included and their key findings.

Mental health challenges

Psychiatric history prior to pregnancy was covered in ten of the thirteen articles. Here, Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (32–33, 35) found that more than half of the women who had an IA also had a pre-pregnancy psychiatric history. Negative associations to the abortion were more prevalent in women with a psychiatric history (32).

These women also had a higher risk of post-abortion mental health problems. More than half of the women who experienced post-abortion mental health problems could therefore be described as having a relapse of their original diagnosis (35).

The study by Toffol et al. (40) explored women’s anxiety levels during the abortion process. They found that a large proportion of the women experienced anxiety immediately prior to the abortion. Nevertheless, the level of anxiety was reduced at the first follow-up three months after the abortion. The women also reported a better quality of life.

Toffol et al. (40) and Lundell et al. (42) also showed that those with a psychiatric history prior to the abortion were also more likely to have had anxiety and a reduced quality of life at the last measurement time point one year after the abortion.

The study by Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) observed uncertainty about the decision to terminate or continue the pregnancy in 32% of the women in the study, while 10% were uncertain about the actual decision to have an IA. Several studies found that pregnant women with a psychiatric history were more likely to feel uncertainty in connection with the decision-making process.

The pregnancy was described as a heavy burden, and the abortion itself was also stressful (32, 35). Lundell et al. (41) also found that women with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSS), regardless of whether it was persistent or transient, were more likely to see a counsellor prior to the abortion. Nevertheless, Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) found no evidence that the decision-making process was associated with post-abortion mental health problems.

Social challenges

The women’s previous experiences had a major impact on how they dealt with the IA (41). Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (34–36) and Lundell et al. (41) found that a large proportion of women who had an IA had experienced major stresses in their life, such as severe physical and psychological abuse.

In addition, one in five women were in an unstable relationship when they fell pregnant. These factors alone could constitute a risk for mental health challenges independent of IA, similar to divorce or the death of a loved one (35).

In several studies, the average age of women who had an IA was 28–30 years (33, 35, 39–42). Many of the women already had children (32–35, 39–41), and many were unemployed (34, 35).

Two of the studies (33, 40) showed that repeated alcohol and drug abuse was more often found among the women in the study who had an IA. Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) pointed out that such substance abuse could increase the risk of post-abortion mental health problems, such as a relapse of their pre-pregnancy substance abuse.

The role of the family

Pohjoranta et al. (39) showed that the majority of women were in stable relationships when they fell pregnant, while Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (33) reported that most were single and lived in urban areas. Few studies, however, mapped the women’s marital status and place of residence. Nevertheless, there was evidence that partner support was important for the women who had an IA.

Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) found that the women received a lot of support from their partners, both during the pregnancy and after the abortion. The women who did not receive such support were more likely to develop depression or bipolar disorder after an IA. None of these women had had mental health challenges in the months leading up to the abortion, and almost half had no psychiatric history.

Pohjoranta et al. (39) found no evidence to suggest that IA affected couple and family relationships. Holmlund et al. (38) nevertheless found that women in stable relationships had less anxiety and a better quality of life after an IA than single women.

Discussion

Although IA has received extensive coverage in the media in recent years, this scoping review shows that the topic is under-researched. In the discussion section, we examine the main findings, which indicate that the women’s pre-pregnancy mental health status had a major impact on their post-abortion mental health.

This finding appears to be linked to factors unrelated to the abortion, such as illness, the death of a loved one, the role of the family and physical or psychological injuries.

Mental health challenges after an IA

Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) found that women were at greater risk of a relapse of a pre-abortion mental disorder than of developing a new one after the abortion. This finding is confirmed by previously published research, which found that women with a psychiatric history prior to pregnancy were most likely to experience post-abortion mental health challenges (14–19).

Our scoping review substantiates this, in accordance with Doane and Quigley (18), who found that the symptoms reported were consistent with the women’s psychiatric history.

Another explanation for how a woman’s psychiatric history may be linked to post-abortion mental health problems was that factors unrelated to the abortion could impact on their post-abortion mental health status (35, 41).

This finding is illustrated by the matching of participants in the study by Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (34) one to one with women who shared their characteristics but had not had an abortion. They found that the effects on post-abortion mental health challenges were most likely due to external factors, and not the abortion itself.

On the basis of these results, Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (34) considered it unlikely that terminating an unwanted pregnancy increased the likelihood of developing mental disorders. Similar findings were documented in Norwegian and international research (16, 23).

Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (34–36) also reported a connection between external factors, such as unemployment, and poorer post-abortion mental health. Such external factors could cause mental health problems regardless of whether the woman had had an IA or continued the pregnancy.

When meeting women in the clinic, it is important to be able to identify factors that make some people more predisposed to post-abortion mental health problems. Many of the women who experienced post-abortion mental health challenges had a psychiatric history prior to pregnancy (16).

Having knowledge of such factors can enable healthcare personnel to provide good information and support to ensure that measures can be initiated at an early stage. A systematic literature study (22) points out that many of the women who had an IA did not feel that their emotional needs were met in the decision-making process. This resulted in several needing to consult a psychologist after the abortion.

The decision-making process

Few of the studies in our scoping review referred to the decision-making process as a challenge for the women. This is in contrast to previous research from Norway examining the decision-making process (20, 24, 45). In order to shed light on the importance of the decision-making process for women, we need to consider the incidence of anxiety and their quality of life following an IA.

Lundell et al. (41, 42) found that women whose pre- and post-abortion mental disorder was of the same severity had the highest levels of anxiety. These women’s anxiety levels remained high up to six months after the abortion (42).

Furthermore, Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) and Toffol et al. (40) found that mental disorders did not necessarily disappear after the abortion in women with a psychiatric history. However, women whose pre- and post-abortion mental disorder differed in severity experienced less anxiety just a few months after the abortion (40, 42).

A similar reduction was found in the literature review by Martucci (13), who described how women were relieved to have the abortion. This was because the pregnancy was a stress factor and crisis event in their life, and the abortion was the solution to the problem.

Toffol et al. (40) showed that women had a better quality of life three months after the abortion than immediately before. This can be viewed in the context of previous studies (20, 24, 45), which indicate that the decision-making process itself constituted a stressor that disappeared after the decision had been made. It was the period between finding out they were pregnant and making the decision to continue or terminate the pregnancy that many women described as the most challenging (16, 21).

Similar findings were reported in the literature review by Petersen et al. (22), who found that women felt they had to make a decision about their plans for the future within a relatively short period of time, and that abortion was the expected choice. However, this was not reflected in our study. Nevertheless, we saw that after they had made the decision to have an abortion, few doubted their choice. We also did not find any evidence of the decision-making process being linked to post-abortion mental health challenges (35).

However, Broen et al. (15) found that those who were unsure about the decision were often plagued by uncertainty in the first six months after the abortion. Thus, lower level of anxiety and higher quality of life partly explain why many women felt both shame and relief at the same time (14, 23).

Partner support

In our scoping review, Van Ditzhuijzen et al. (35) and Holmlund et al. (38) showed that women’s mental health status was linked to the support they received from their partner. This finding was reflected in the fact that women who did not receive such support were more likely to develop post-abortion mental health challenges, on a par with women who were in unstable relationships (35).

This finding was consistent with the systematic literature review by Petersen et al. (22), which found that women put a high value on partner support. As in our scoping review, they found that the IA did not affect their relationship with their partner (39). Petersen et al. (22) explained this finding with the idea that IA was an event that brought the couples closer together, even if the partner often had a negative attitude towards the pregnancy and wanted the woman to have an abortion.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A weakness of the study was that some of the source data was based on the same participants. The articles were nevertheless included due to the lack of research on the topic. Although the articles from DAMHS (32–36) were based on the same participants, different control groups were used in the analyses.

Furthermore, some of the same analyses were repeated with data obtained from the participants at a later date. The analyses led to both new and supplementary findings, but also to some corrections of findings already presented.

An earlier literature review also revealed an absence of control groups in clinical studies in the field and poor definitions of the psychologic symptoms experienced by women (18). We believe that the articles included in our study have generated knowledge about which psychological symptoms and challenges may have significance for the women.

It is important to note that even though the articles were selected from countries with similar abortion laws, the type of findings reported by the countries may vary due to country-specific differences. There is also the possibility that IA in the control groups is underreported, even if the countries that are included have an open dialogue and a policy that supports women’s right to abortion (3–6).

The results in our study are nevertheless consistent with the results of Petersen et al. (22), who found that the decision-making process was challenging for many of the women, and that support from someone close was important for them.

Conclusion

To date, there is little research on IA and the impact it has on women’s mental health in countries where abortion laws are similar to those of Norway. This study has generated knowledge on women’s post-abortion mental health. The study shows that it is important to be aware that external factors such as unemployment may be linked to women’s post-abortion mental health.

Most women who faced mental health challenges after an IA had had similar challenges before the pregnancy. It may therefore be appropriate to pay particular attention to how women with a psychiatric history deal with abortion. This will enable healthcare personnel to initiate relevant health care at an early stage.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Comments