How nurses use experience from clinical placement in Madagascar in their daily work

The nurses remember how it felt to be an outsider, and therefore try to take a conscientious approach to minority patients.

Background: It is a national goal for half of all students to complete an international clinical placement. Student exchanges have proven to be important for achieving intercultural competence, but there is a lack of knowledge about how nurses use this competence in future practice. Such competence is necessary for meeting the need for equal access to health and care services in a multicultural society.

Objective: The objective of the study was to develop knowledge about how qualified registered nurses (RNs) in Norway use the experience gained from clinical placement in the Global South in their daily work.

Method: The study has a qualitative design that includes both a questionnaire with open-ended questions (n = 77) and individual interviews (n = 4) with qualified RNs who completed clinical placement in Madagascar. The data were collected in online questionnaires in May 2020 and interviews were held in the autumn of 2020. The informants were asked about clinical placement in Madagascar, and how they use the learning outcomes in their daily work.

Results: The study shows that the experience gained from clinical placement in the Global South provides intercultural competence, and also leads to personal and professional growth. In retrospect, the informants point out that as qualified RNs they try to have a conscientious approach to minority patients because they remember how it felt to be an outsider. The perspective of gratitude, which is largely linked to inequalities in health services, has motivated many RNs to help realise the goal of equal access to health and care services.

Conclusion: The study shows that the RNs acquired intercultural competence during clinical placement in Madagascar. They report that they use this competence actively in their work with patients from other cultures. Our findings indicate that former international exchange students can serve as bridge-builders by recognising the needs of minority patients whilst also helping them adapt to the Norwegian context. This suggests that clinical placement in the Global South should continue to be a core component in the Norwegian nursing education.

The number of inhabitants with a minority background is constantly increasing in Norway (1). This means greater cultural diversity, which requires a broader range of competence in RNs (2, 3).

A stronger focus on internationalisation for nursing students could be one way of meeting the need for equal access to health and care services. The Ministry of Education and Research has set a goal for half of all students to complete an international clinical placement (4).

Internationalisation can help ensure that students gain an intercultural understanding and develop the ability to solve problems, show initiative, exercise creativity and foster collaboration and change (4). This is in line with the regulations on national guidelines for nursing education: ‘The candidate must use cultural competence and cultural understanding in the assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation of nursing care’ (5).

In this article, we build on Dahl’s understanding of intercultural competence, i.e. ‘the ability to communicate adequately and appropriately in a given situation with people from different backgrounds. This requires appropriate behaviour, adequate knowledge and ethics’ (6, p. 294).

With a view to internationalisation, Norwegian educational institutions facilitate clinical placement in the Global South. Learning outcomes from such placements can include personal and professional growth, improved language skills, development of intercultural competence and knowledge about global health and health systems in other countries (7–12).

However, it cannot automatically be assumed that students learn relevant competence in clinical placement in the Global South. Studies show that factors such as language and major differences in resources and in the practice of nursing between Norway and the host country can hinder the exchange of knowledge (13). The result is also dependent on effective follow-up and supervision of the students (10–12).

Most studies of nursing student exchanges to Africa have been conducted shortly after completion of the clinical placement, and do not tell us very much about how nurses apply their practical experience from abroad to future practice (10, 11, 13–15).

Previous research therefore calls for more studies to find out more about the extent to which qualified RNs are able to use their clinical placement experience in their daily work in the health service (8, 16). Figure 1 provides some facts about Madagascar.

Objectives and research questions

The objective of the study is to develop knowledge about how qualified RNs use their experience from clinical placement in the Global South in their daily work in Norway. Key questions relate to the benefits of Norwegian nursing students travelling abroad to low-income countries like Madagascar, and how they report using this in their daily work.

Method

The study has a qualitative and exploratory design in which open-ended questions were asked in an anonymous questionnaire and individual in-depth interviews. We thus managed to obtain a large dataset from the survey, whilst also gathering more in-depth information about the informants’ experiences in individual interviews (19).

Material

Data were collected via an online questionnaire in May 2020. In the questionnaire, the informants were asked about the clinical placement in Madagascar and how they use their experiences from this in their daily work. In the individual in-depth interviews, a semi-structured interview method was used to explore what the informants felt they had learned from clinical placement in Madagascar, and how they use this competence in their nursing practice.

In the interviews, we used an interview guide that contained 17 questions divided into three thematic areas. This guide was designed with the aim of addressing the research question. The informants were given the opportunity to talk freely about the different topics, and some accounts addressed several of the questions in the interview guide.

The interviews were conducted via Zoom in the autumn of 2020, and the recordings were transcribed verbatim by the second author. Each interview lasted between 45 and 60 minutes.

Sample and data collection

In the period from autumn 2016 to spring 2019, 120 nursing students from several Norwegian educational institutions were on clinical placements of 4 to 12 weeks at various health institutions in Madagascar. The nursing students worked in association with a local competence centre and were recruited to the study through the study coordinator at the centre via already established Messenger chat groups.

All former nursing students who had a clinical placement in Madagascar during the relevant period were invited to participate in the study. Selection criteria were completed nursing education, at least one year of work experience as a nurse, and clinical placement in Madagascar.

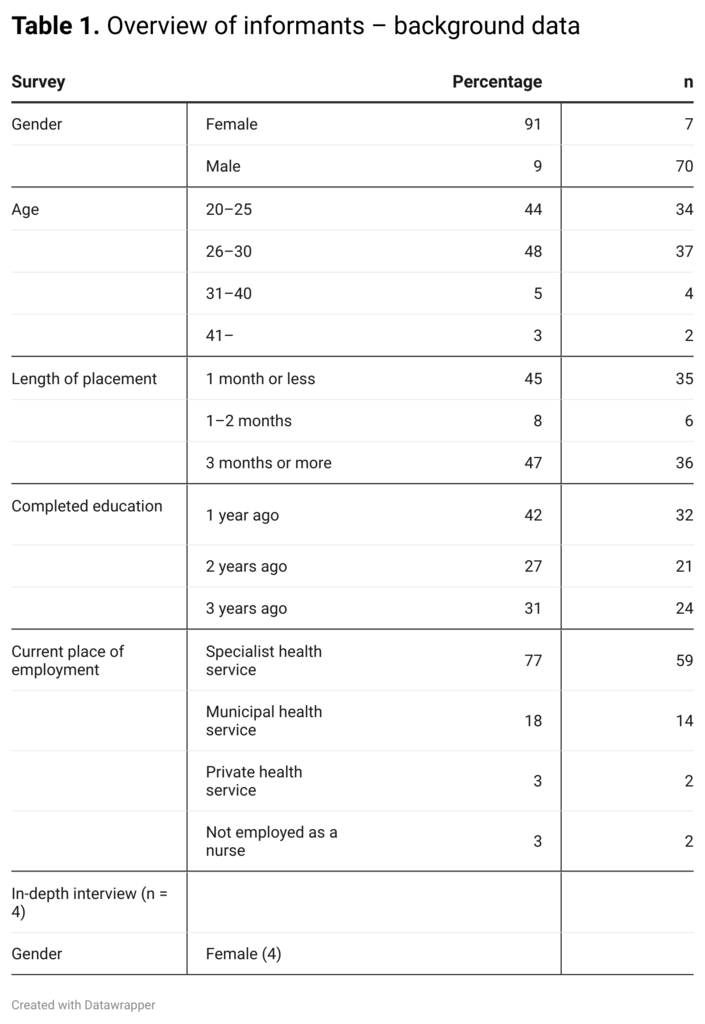

A total of 77 informants completed the entire questionnaire and met the selection criteria. Four informants were recruited via the questionnaire and took part in in-depth interviews conducted by the first author (LSA) and a colleague. Table 1 gives an overview of the informants.

Data analysis

The texts were analysed using systematic text condensation according to Malterud’s (20) four-step content analysis method. The aim was to obtain knowledge about the informants’ experiences during clinical placement, and how this has benefitted them in future practice.

The analysis process has gone back and forth between the various steps in several phases, and has not therefore been a linear process. In the first step, we familiarised ourselves with the material by reading the texts individually. This gave us an indication of preliminary themes (20).

We first read the answers to the open-ended questions in the survey and then the interviews. The themes that emerged in the in-depth interviews corresponded to those from the survey, and we gained a deeper understanding of these themes, but no new themes emerged.

In the second step, we returned to the texts and identified meaning units. Each of the authors colour-coded the units separately, which led to different code groups clearly emerging. We then jointly ensured that the various meaning units were placed in the right code group.

In the third step, we divided the code groups into several subgroups. We did this individually before discussing which subgroups were most relevant to our further work on the text.

The next step was to condense the content using artificial quotes based on a summary of several meaning units from the same subgroup. The code groups also changed during the process since the subgroups provided new insight into what would be relevant to include.

The fourth and final step was recontextualisation. The findings, which are loyal to what the informants reported and give the reader insight and understanding (20), were summarised in sub- and main categories. In the final step, these were presented in the results section.

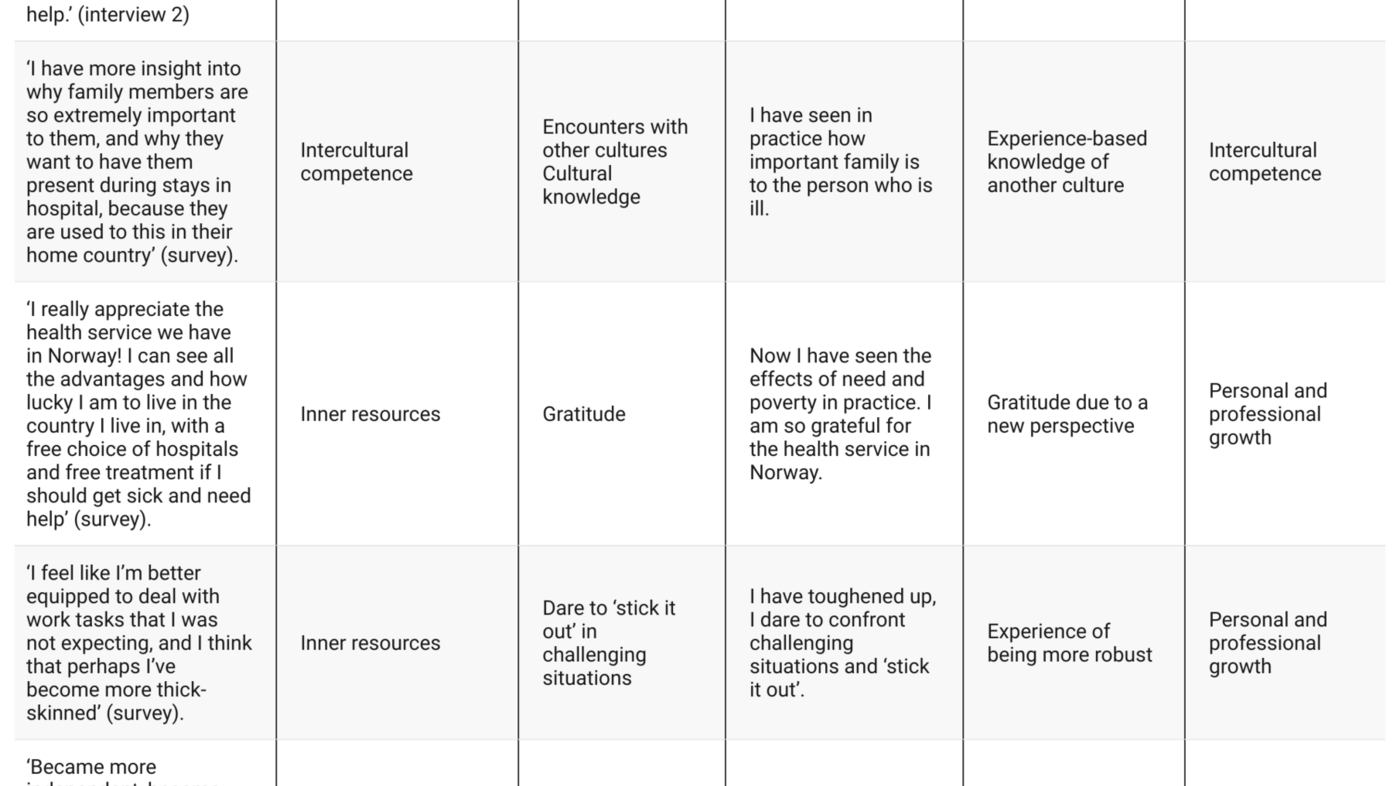

An excerpt of the analysis, from steps 2 to 4, is shown in Table 2. Here we deviate slightly from Malterud (20), whose model uses categories as opposed to sub- and main categories.

Ethical aspects

The study was evaluated by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), reference 297455. All informants provided informed consent.

Results

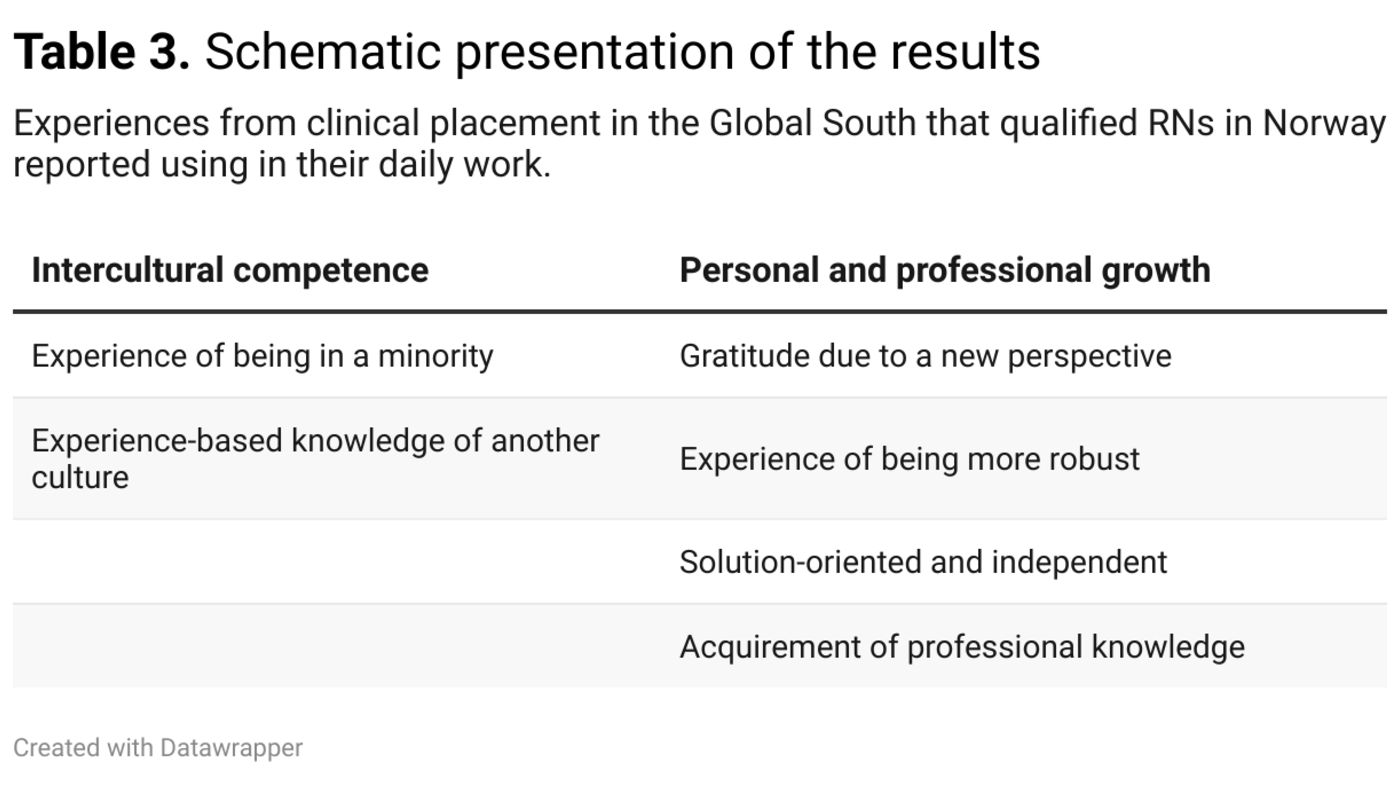

The findings from the study show that clinical placement in Madagascar leads to ‘intercultural competence’ and ‘personal and professional growth’, which is useful for future nursing practice (Table 3).

Intercultural competence

Experience of being in a minority

When the students describe the experience of being a Norwegian student in Madagascar and their encounter with a new culture, they use terms such as ‘being an outsider’ and ‘being a foreigner’:

‘It’s something I’ve thought about a lot in hindsight. I was able to experience what it felt like being the outsider, the one being seen as different’ (interview 4).

‘Being an outsider’ is described by the informants as an uncomfortable feeling of loneliness and of being the one who needs help and not understanding what is going on. The informants describe how, as qualified RNs, they try to have a conscientious approach to minority patients because they remember what it felt like to be the outsider:

‘I’m aware of when a patient cannot speak the language well, and we’re standing there talking in our language at our own speed. I can remember how uncomfortable that can be, because I couldn’t understand anything. I try not to talk over the heads of these patients and to use an interpreter or translation tool where possible, so that we understand each other at least to some extent’ (interview 1).

Several informants indicate that the learning outcome from such experiences has a high transfer value in their work in Norway with patients from other cultures.

Experience-based knowledge of another culture

Many of the informants describe how they now find it easier to deal with patients from another culture than prior to the clinical placement. They describe this new knowledge as insight into traditions, values and attitudes, which in turn provides greater understanding of the context of minority patients’ backgrounds:

‘I now have a better understanding of the culture of patients from other countries. I understand their scepticism about health care, and the positive and negative attitudes towards healthcare professionals. It’s easier to understand their situation’ (survey).

The informants now find it easier to deal with patients from another culture than prior to the clinical placement.

The role of patients’ families in health care is a recurring theme among the informants. One informant gained a better understanding of how families need to show compassion and express their desire for the patient’s recovery, while in Norway we are more preoccupied with rules and procedures:

‘Here it’s very much like, “No, no. The patient needs peace and quiet, and should only have a maximum of two visitors in their room, and preferably not too many visits.” But my experience abroad has made me look at this a little differently now. We need to find a solution that suits both parties, so that they don’t feel rejected’ (interview 4).

The informants say that they learned about other illness aetiology. One informant describes how she uses the experiences from a village with mentally ill patients, where the threat of witchcraft and the driving out of spirits were key elements:

‘I can see many similarities between the patients we met in the Madagascan village and the patients here from other countries. The witchcraft and evil spirits and all that. I get asked at work about my experiences and about how to deal with patients who think they are bewitched’ (interview 1).

However, several informants also report that they find it difficult to explain how they use the experiences they have gained in their daily work:

‘But it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what it is from Madagascar that informs my nursing’ (interview 3).

The informants possess knowledge that they are not fully aware of. This statement illustrates the paradoxical nature of this:

‘I don’t always have a good answer, but I tend to have some insight or experience that I can share’ (interview 1).

Personal and professional growth

Gratitude due to a new perspective

The informants describe how their experiences from Madagascar made them feel grateful. They describe the phenomenon of gratitude in relation to the resources in the Norwegian health service, their personal well-being and the privileges we enjoy in Norway.

The RNs remember working with patients who were denied life-saving treatment or relief for severe pain due to the lack of resources in the health service. Many of the informants said that it is these experiences that gave them perspective:

‘I’m now more aware of, or have first-hand experience of, the major inequalities in the world. We are so privileged here. It gives you a whole new perspective on things’ (interview 3).

Some of the informants also point out that this perspective makes them want to help foster change at home in Norway and to safeguard universal access to health care. One informant describes how she is now an advocate of equal access to health care for immigrant women because of her experiences in Madagascar. The informants highlight those who are marginalised for various reasons:

‘I work in the field of substance abuse, where there are a lot of wounds. I’m now trying to persuade my employer to let us perform simple wound management for patients with poor self-care. If they’re able to heal the terrible surgical wounds we saw in Madagascar using only gauze and salt water, surely a welfare state like Norway can provide an easily accessible service for those who lack self-care skills’ (survey).

Experience of being more robust

The informants describe the experience of being more robust as developing qualities such as courage, endurance, ‘daring to stick it out’ in difficult situations and becoming thick-skinned. In the survey and interviews, many informants describe tough episodes they have encountered in clinical placement. For example, children who have died, parents who could not afford to pay for a child’s medical treatment, or situations where patients were treated poorly due to their lack of resources or knowledge.

The informants indicate that clinical placement has developed them as human beings and as nurses.

The informants indicate that clinical placement has developed them as human beings and as nurses. One explained that she is better able to cope now with difficult situations in Norway:

‘My clinical placement experience in Madagascar means that I often dare to deal with situations that I find frightening and challenging’ (survey).

Solution-oriented and independent

Many informants are aware that conditions in a low-cost country like Madagascar mean that they need to think and act differently, and that these are characteristics and competence that can be useful in the Norwegian health service:

‘I would say that I’m much more independent and good at making decisions. I can think in more practical terms and outside the box. But I’m also flexible and solution-oriented’ (survey).

An example of being more solution-oriented is given by one of the informants who links their experiences with the reuse and lack of equipment in Madagascar to the specific work situation in Norway:

‘Some experiences stay with you, and now in the midst of a global pandemic, I’m drawing on my experiences from working in conditions where equipment has to be reused. You need to think differently and creatively when equipment runs out. I’ve become very creative in my thinking when it comes to solution-oriented nursing’ (survey).

Acquirement of professional knowledge

Several informants acquired a direct professional benefit from clinical placement in Madagascar:

‘The clinical experience is useful for future practice. I learned anatomy and physiology in clinical placement in a surgical ward, and saw the consequences of conditions going untreated’ (survey).

This sentiment was also reflected in statements about how nursing students in Norway learn a lot about training the clinical eye, but how the use of various medical instruments actually negates the need to use this knowledge:

‘If I’m unsure, I’ll grab some medical instrument or other. In Madagascar, you have to think for yourself and use what you have’ (interview 4).

Others also point to the value of repetition in clinical placement in Madagascar – for example, vaccination, inserting peripheral venous cannulas, and examining and treating children. Such statements indicate that the informants consider the professional competence acquired during clinical placement to be useful in professional practice in Norway.

Discussion

The aim of the study is to develop knowledge about how qualified RNs in Norway use the experience gained from clinical placement in the Global South in their daily work.

Intercultural bridge-builders

Equal access to health and care services is a goal for the Norwegian welfare state (2). This means that services must be adapted and arranged to suit the needs of the individual patient (3). The barriers that impede equal access to healthcare services for patients from minority groups have been shown to include language barriers, a low level of health literacy among patients, a lack of trust in the health service, differences in illness and health aetiology, and a lack of knowledge about patients’ cultures among healthcare personnel (3).

A study by Alpers and Hanssen (21) found that qualified RNs in Norway lack knowledge about the illness aetiology and medical traditions of non-Western cultures. This makes it difficult for healthcare personnel to understand the wishes, needs and behaviour of patients from minority groups and their families. Research also shows that a lack of intercultural competence impacts on patient care and exacerbates health inequalities (22).

The informants’ descriptions of how they apply their experience from clinical placements in Madagascar seem to indicate that they have acquired intercultural competence (6). In both the survey and the interviews, it was apparent that informants felt that they had become more aware that people’s experiences and perceptions can differ from their own. This demonstrates that they have gained insight into how a different set of beliefs, illness aetiology and perception of the role of the patient’s family can affect the nursing needs of the patient.

The feeling of being a foreigner and an outsider is something they are now able to use in contact with patients who have an immigrant background.

Several of the informants described how the feeling of being a foreigner and an outsider was something they were now able to use in their work with patients who have an immigrant background. This suggests that experiences from clinical placement make it easier for them to understand and show empathy for patients who have a different cultural background.

The informants explained that they employed different communication techniques, such as using interpreting services, to increase mutual understanding. This finding is in accordance with previous studies and it shows that clinical placement in the Global South can help break down some of the barriers to equal access to healthcare services for patients from minority groups (9, 11).

Our findings indicate that former nursing students who have completed a clinical placement period in the Global South can, ideally, take on the role of bridge-builder, as they are able to see the needs of minority group patients whilst also helping them adapt to the Norwegian context. On the basis of their experiences in Madagascar, the informants understand the value of being familiar with the background and culture of the patient, and they are able to make adjustments accordingly. This is in line with the key learning outcomes in the regulations on national guidelines for nursing education (5), as mentioned in the introduction.

Many of the informants in our study state that they have learned a great deal from their clinical placement in Madagascar. However, it is also clear that many of them find it difficult to express in words what they have learned and that they struggle to transfer their experience to working life in Norway, especially with regard to intercultural competence.

This is a well-known problem found in studies focusing on transforming learning experiences to sustainable knowledge for future practice (23). It may indicate that students undertaking clinical placement in the Global South have a greater need than other students for guidance and tools, both during and after completing their placement, as other studies also show (10–12).

The perspective of gratitude and social involvement

In the survey, many of the informants indicated that one of the greatest benefits of clinical placement in Madagascar was the sense of perspective they developed. This was particularly linked to the poverty they encountered as well as the lack of resources in the health service. Does the feeling of gratitude acknowledged by the informants have relevance in the workplace? In the interviews, the perspective of gratitude was linked to a stronger commitment to help minority groups and those on the margins of society in Norway.

Gratitude can serve an important purpose in providing a basis for solidarity with people less fortunate than ourselves. The government white paper on international student mobility in higher education (Meld. St. 7 (2020–2021)) (4), points to social involvement as a benefit for students who travel abroad and indicates that this is a skill and attribute that can be useful later in connection with work. The white paper suggests that this effect is more a result of staying in a foreign country than the content of the study programme or work placement. This indicates that for many of the informants, the perspective of gratitude has become a motivation for them to work towards the goal of equal access to health and care services.

The experience of gratitude has also been found in other studies of clinical placement experiences in low-income countries (9, 10). In contrast to the ethnocentric gratitude identified in the study by Hovland and Johannessen (10), where the informants show a condescending and critical attitude towards the health service and the competence of the healthcare personnel in the host country, the informants in our study are generally more positive towards the local health service.

It is possible to find similar attitudes among some of our informants, but the majority of the participants in our study expressed admiration over how much the local healthcare personnel were able to accomplish with so few resources.

The differing attitudes do not necessarily mean that the informants in our study are more culturally sensitive than those in the study by Hovland and Johannessen (10), but may be because a longer space of time had elapsed between the informants’ clinical placement and the interview in our study. However, the ability of students to participate in self-reflection, and the supervision and guidance they receive during the clinical placement can also contribute to forming these attitudes, as Hovland and Johannessen point out.

Personal growth

In line with the previous national guidelines for nursing education (24) and the new regulations (5), it is a primary aim to educate independent, responsible and innovation-oriented professionals. The informants’ responses show that although many of the experiences they had in clinical placement were ‘unpleasant’, they had still managed to have a valuable learning experience. An example of such learning is the increased development of insight into their own competence.

Both personal and professional growth are topics that recur in many studies that address the benefits of student exchange programmes (8, 9, 15, 16). In our study, we discuss how these forms of growth can be useful when working as a qualified RN.

Participants described how they had developed their creativity, and how they felt they had become more robust and dared to ‘stick it out’ in challenging situations.

One study (9) found that nursing students who had carried out a clinical placement abroad had developed individual skills and gained cultural competence that they were able to use later in working life. This corresponds with our results, in which participants explained that they had developed their creativity and felt that they had become more robust and ‘dared to stick it out’ in difficult situations. These are important qualities for a capable nursing professional facing a challenging working day in Norway.

Gained professional knowledge despite barriers

One study comparing students on international exchanges in high-income countries and low-income countries found that it was more difficult for the latter group to develop professionally (7).

In our study, several informants felt that they had gained cultural and personal insight as a result of clinical placement, in addition to professional knowledge. Increased knowledge about anatomy and physiology, training in developing the clinical eye and repetition were areas that the informants mentioned specifically. Previous studies have mainly focused on learning outcomes in the form of intercultural competence and personal development, and have had little focus on the professional knowledge gained through clinical placement in the Global South (8, 10, 11).

This article shows that Norwegian students can also obtain professional knowledge from these types of placements, despite significant socioeconomic differences and cultural barriers. However, this is conditional on the students being well-prepared, having clear course requirements for the clinical placement and having supervisors that follow up the students’ reflections during the placement period (8, 9).

Implications for nursing education and further research

Our findings show that informants achieved learning outcomes as a consequence of clinical placement in the Global South, but that it can be difficult for them to translate this competence into actual words and actions. This suggests that students who carry out clinical placement in the Global South have a greater need for guidance.

Emphasis should be placed on giving students guidance in how to use their experiences and learn from them, so that they are able to use the competence gained in a Norwegian context. There is also a need for more research to follow up the long-term benefits of international clinical placement and its relevance for work in the Norwegian health service.

Strengths and weaknesses

One strength of the study is that it provides knowledge about the experience of clinical placement, via in-depth interviews and written responses to the survey. However, only four in-depth interviews were conducted and some of the free-text responses were rather brief. Moreover, we do not know if the 40 odd people who did not respond to the survey felt that they had learnt anything.

A weakness of the study is that it only features informants who have been in Madagascar, and we cannot therefore generalise the findings to clinical placements in other countries. However, we have included a broad selection of former students from different educational institutions in Norway who carried out clinical placement in Madagascar over a time span of several years.

In our study, we did not examine whether there were systematic differences between the experiences of students in four-week placements and those in twelve-week placements, but our review of the data did not reveal any obvious differences. This is an area that requires further research.

Conclusion

The study shows that RNs acquired intercultural competence as a consequence of clinical placement in Madagascar, which they report using actively in working with patients from other cultures. Many of the informants said it is now easier to address patients from another culture than it was before the clinical placement, and indicated that they benefitted from the exchange both from a professional and personal perspective.

Our findings indicate that former international exchange students can take on the role of bridge-builder, as they are able to see the needs of minority group patients whilst also helping them adapt to the Norwegian context. This suggests that clinical placement in the Global South should also have a key place in Norwegian nursing education in the future.

References

1. Folkehelseinstituttet. Befolkningen i Norge. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 2018. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/nettpub/hin/befolkning/befolkningen/ (downloaded 07.04.2021).

2. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Likeverdige helse- og omsorgstjenester – god helse for alle. Regjeringen.no; 2013. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/likeverdige-helse--og-omsorgstjenester/id733870/ (downloaded 07.04.2021).

3. Jakobsen MD, Spilker RS. Innvandrere og brukermedvirkning i helse- og omsorgstjenestene. Hvordan ivareta innvandreres brukermedvirkning i avgjørelser om egen helse, utforming av tjenester og tjenesteforskning. En oppsummering av kunnskap. Senter for omsorgsforskning; 2020. Available at: https://omsorgsforskning.brage.unit.no/omsorgsforskning-xmlui/handle/11250/2686528 (downloaded 02.02.2022).

4. Meld. St. 7 (2020–2021). En verden av muligheter – internasjonal studentmobilitet i høyere utdanning. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2020. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-7-20202021/id2779627/ (downloaded 07.04.2021).

5. Forskrift 25. januar 2008 nr. 128 til rammeplan for sykepleierutdanning. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2008-01-25-128 (downloaded 07.04.2021).

6. Dahl Ø. Møter mellom mennesker: innføring i interkulturell kommunikasjon. 2nd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2013.

7. Granel N, Leyva-Moral JM, Morris J, Šáteková L, Grosemans J, Bernabeu-Tamayo MD. Student’s satisfaction and intercultural competence development from a short study abroad programs: A multiple cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;50(01):102926. DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102926.

8. Dietrich Leurer M, Kent-Wilkinson AE, Luimes J, Murray L, Squires V, Ferguson LM, et al. Reflections on study abroad: insights from registered nurses. Qual Adv Nurs Educ. 2020;6(1). DOI: 10.17483/2368-6669.1225

9. Jansen MB, Lund DW, Baume K, Lillyman S, Rooney K, Nielsen DS. International clinical placement – experiences of nursing students’ cultural, personal and professional development: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;51(2):102987. DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.102987

10. Hovland OJ, Johannessen B. Sykepleierstudenter utvikler kulturell kompetanse på utveksling i Tanzania. Sykepl Forsk. 2018;(73782):e-73782. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2018.73782

11. Ulvund I, Mordal E. The impact of short term clinical placement in a developing country on nursing students: a qualitative descriptive study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;55(8):96–100. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.05.013

12. Gower S, Duggan R, Dantas JAR, Boldy D. Something has shifted: nursing students’ global perspective following international clinical placements. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(10):2395–406. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13320

13. Tjoflåt I, Razaonandrianina J, Karlsen B, Hansen BS. Complementary knowledge sharing: experiences of nursing students participating in an educational exchange program between Madagascar and Norway. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;49(02):33–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.011

14. Morgan DA. Learning in liminality. Student experiences of learning during a nursing study abroad journey: a hermeneutic phenomenological research study. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;79(8):204–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.05.036

15. Edmonds ML. An integrative review of study abroad programs for nursing students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(1):30–4. DOI: 10.5480/1536-5026-33.1.30

16. Roy A, Newman A, Ellenberger T, Pyman A. Outcomes of international student mobility programs: a systematic review and agenda for future research. Stud High Educ. 2019;44(9):1630–44. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1458222

17. The World Bank. The World Bank in Madagascar. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/madagascar/overview#1 (downloaded 01.09.2021).

18. United Nations. Madagaskar. Available at: https://www.fn.no/Land/madagaskar (downloaded 01.09.2021).

19. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 3rd ed. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

20. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

21. Alpers L-M, Hanssen I. Caring for ethnic minority patients: a mixed method study of nurses’ self-assessment of cultural competency. Nurse Educ Today. juni 2014;34(6):999–1004. DOI: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.004

22. Papadopoulos I, Shea S, Taylor G, Pezzella A, Foley L. Developing tools to promote culturally competent compassion, courage, and intercultural communication in healthcare. J Compassionate Health Care. 2016;3(1):2. DOI: 10.1186/s40639-016-0019-6

23. Askeland GA, Døhlie E, Grosvold K. International field placement in social work: relevant for working in the home country. Int Soc Work. 2018;61(5):692–705. DOI: 10.1177/0020872816655200

24. Kunnskapsdepartementet. Rammeplan for sykepleierutdanning. Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet; 2008. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/vedlegg/uh/rammeplaner/helse/rammeplane_sykepleierutdannin_08.pdf (downloaded 07.04.2021).

Comments