Accept or decline? Nurses and patients as Facebook friends

All the nurses in the study had received friend requests from patients. They had different, and sometimes conflicting, attitudes to contact with patients on Facebook.

Background: Revised ethical guidelines for nurses include requirements about digital common sense and conduct. Facebook friendships between nurses and patients can test professional boundaries by jeopardising privacy protection and the nurse’s professional role. Previous studies reveal a variety of attitudes to Facebook friendships between health professionals and patients; nonetheless, health professionals’ experiences with social media have been under-researched.

Objective: The study seeks to describe nurses’ experiences and reflections around their own and their colleagues’ contact with patients on Facebook.

Method: The study is based on interview data from a doctoral thesis on professional boundaries between nurses and patients in the mental health service. In individual interviews, 14 experienced nurses, most with advanced training in mental health care, shared their experiences and reflections around their own and their colleagues’ use of Facebook. The group of nurses comprised eleven women and three men from 40 to 60 years of age. Eleven of them worked in the specialist health service, and three worked in the primary care health service.

Results: The nurses found that having contact with patients on Facebook could test professional boundaries and roles, partly because it could blur the line between their work and their private life. There was variation with regard to whether they chose to use Facebook at all, and if they did, how they used it. The nurses described different, and sometimes conflicting, attitudes to contact with patients on Facebook. All the nurses who used Facebook had received friend requests from patients. Some nurses chose to accept the friend requests and had various reasons for doing so. For example, some thought that having contact on Facebook was not especially personal.

Conclusion: Contact between nurses and patients on Facebook can test professional, ethical and legal boundaries. Digital common sense for nurses must involve critical assessments of how social media can affect the nurse-patient relationship. Such assessments are examples of skills that are part of the learning outcomes for technology and digital competence in the nursing education.

Facebook is the most used social media platform in Norway, and the percentage of the population that uses Facebook on a daily basis has increased from roughly 50 per cent in the mid-2010s (1) to 69 per cent in 2020 (2).

A study from 2020 showed that one in four nurses had a positive view of being friends on social media with former patients or their family (3). Other studies of health professionals report both higher and lower percentages (3–7).

Contact between health professionals and patients on social media platforms such as Facebook has ethical as well as legal implications. In the spring of 2019, the ethical guidelines for nurses in Norway were revised and approved (8). The revision includes requirements regarding nurses’ conduct on digital media and expectations about digital common sense.

Guidelines for social media use

In the autumn of 2019, the Norwegian Council for Medical Ethics presented new guidelines and advice on doctors’ use of social media (9). Unlike the general wording on digital common sense and conduct in the ethical guidelines for nurses, the Council states that doctors should not be Facebook friends with patients.

The Norwegian Medical Association asks doctors to consider ‘whether being friends with patients on social media can affect the doctor-patient relationship’ (9). Both the Norwegian Directorate of Health (10) and the Council for Medical Ethics recommend that doctors decline friend requests but that they should explain their reason for doing so.

The guideline on avoiding contact with patients on social media has two purposes: privacy protection and the nurse’s professional role. Nurses have a legal responsibility to uphold their duty of confidentiality (11) and an ethical duty to protect patients’ confidential information (8).

Guidelines on social media use often address the topic of privacy protection (12). When nurses and patients connect on social media, there is a risk that outside individuals will gain knowledge of the patient relationship or that sensitive information will fall into the wrong hands (13).

Moreover, professional guidelines specify that nurses must be cognisant of their professional role vis-á-vis patients (8).

Previous research on this topic

A database search revealed that breaches of personal privacy and vague professional boundaries are typical ethical problems in studies on the use of social media by health professionals (14–15).

According to a study from 2020, health professionals’ perceptions and experiences related to social media have been under-researched (3). With a view to the legal and ethical framework for the nurse-patient relationship, it is important for nurses to decide whether and to what extent they should be accessible to patients on social media.

Objective of the study

The objective of this study was to describe nurses’ experiences and reflections around their own and their colleagues’ contact with patients on Facebook.

The aim of the study was to gain insight into nurses’ experiences regarding professional boundaries in social media with a view to helping nurses deal with ethical dilemmas and support their practice of digital common sense by providing nuance to official advice and guidelines.

Method

The study was based on qualitative interview data from the author’s doctoral thesis on professional boundaries between nurses and patients in the mental health service (16).

Relational work is the hallmark of mental health care, and the close relationships between nurses and patients can test professional boundaries, including through contact outside of work, such as on social media.

Sample

Sixteen nurses took part in the doctoral study. In individual interviews, 14 of the 16 nurses shared their experiences and reflections around their own and their colleagues’ use of Facebook. It is these nurses who comprise the sample for this study.

Of the 14 nurses, 11 were women and three were men; 11 worked in the specialist health service and three in the primary care health service. They ranged in age from 40 to 60 years old. The amount of time since they had completed their nursing education varied from five to 37 years, and 13 of 14 had advanced training in mental health care.

The doctoral study employed a sampling strategy that combined convenience sampling with the snowball technique. In order to increase variation in the sample, the author recruited participants from both the specialist and the primary care health services in a city and in some smaller towns in central Norway.

Data collection

The author interviewed the participants in the period from September 2013 to March 2014. The interviews were individual and semi-structured, and the interview guide included the topic of social media. The author made digital recordings of the interviews and then transcribed them.

Most of the participants were interviewed twice, while three of them were interviewed three times. The topic of social media was usually brought up in the second or third interview. The questions mainly focused on whether the participants used Facebook or other social media and whether they had contact with patients on social media.

Analysis

The analysis took its point of departure in describing the nurses’ experiences and reflections around their own and their colleagues’ contact with patients on Facebook. The participants who did not use Facebook at the time of the interviews reflected on their choice to not be on Facebook and on their colleagues’ use of the platform.

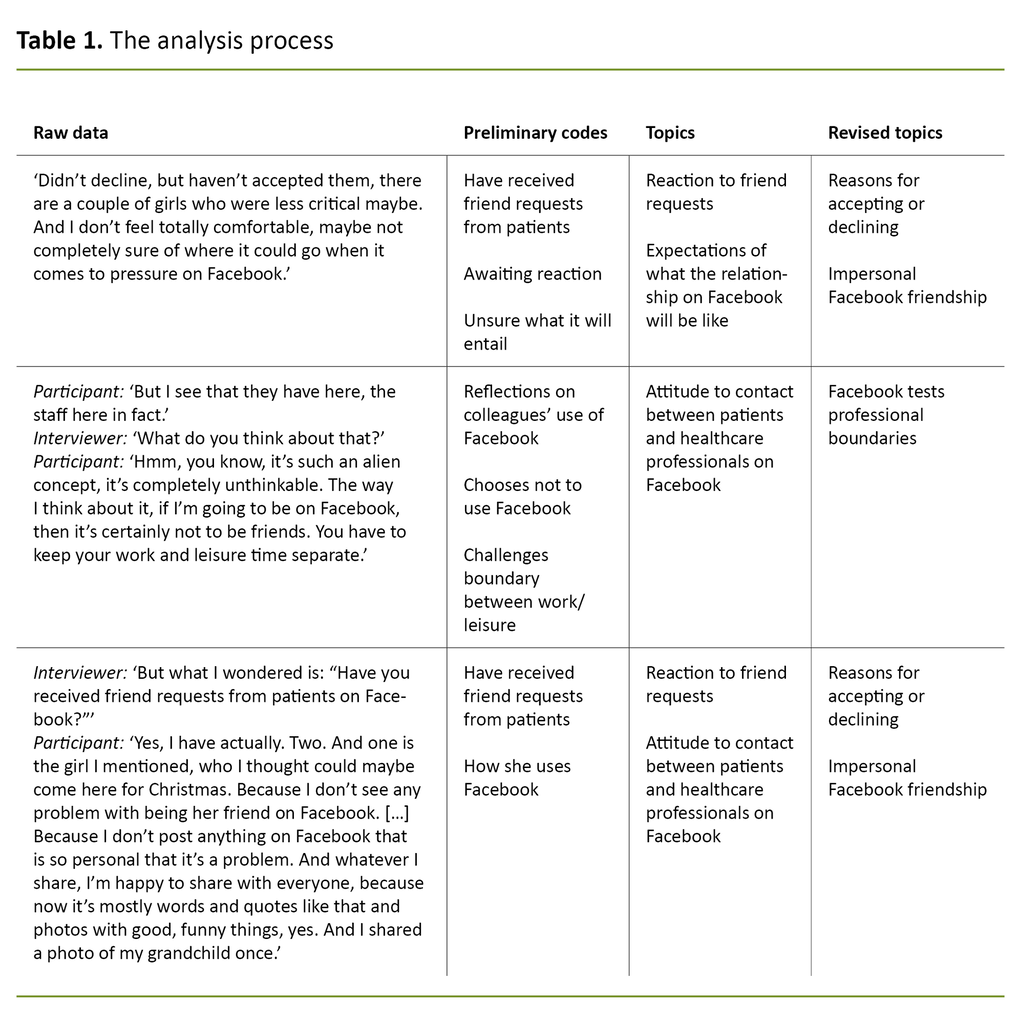

The analysis process was based on Braun and Clarke’s (17) thematic analysis, and NVivo 12 software was used to code the data, which comprised 30 pages of text. Codes were processed and interpreted in multiple rounds, during which the topics were revised.

Table 1 illustrates the process from raw data to final topics. Table 2 shows which participants talked about the various topics.

Research ethics

Participation in the study was voluntary, and the participants received verbal and written information. The doctoral study was registered with the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD), now known as the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, project number 34079.

Personal information has been handled in accordance with NSD guidelines; for example, personally identifiable data have been anonymised and audio recordings have been erased. The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC) concluded that the study could be conducted without its approval.

Results

Eight of the 14 nurses in the study used Facebook. All eight had received friend requests from patients, of which five chose to accept some friend requests. Both the nurses who used Facebook and those who did not reflected on how Facebook could test professional boundaries in the nurse-patient relationship.

The nurses had different reasons for either accepting or declining friend requests from patients. The Facebook friendships in themselves could be relatively impersonal.

Facebook tests professional boundaries

The nurses found that having contact with patients on Facebook could test professional boundaries. For instance, they felt it was not appropriate to send messages to patients on Facebook because this involved a mixing of roles.

Several nurses stated that Facebook should be reserved for their private life. One of them said, ‘The way I think about it, if I’m going to be on Facebook, then it’s certainly not to be friends. You have to keep your work and leisure time separate.’

Two nurses said that they chose not to be on Facebook because of their work as a nurse. One of them said, ‘I accept the consequences of my being here and the profession I have’. She explained that if she had been on Facebook, she would have received friend requests from patients, and she was not interested in ‘sitting there and clicking on decline’.

Several nurses stated that Facebook should be reserved for their private life.

The other nurse used to be on Facebook but found that it led to problems she did not want to deal with.

The nurses found that their colleagues had different practices regarding contact with patients on Facebook. ‘We have actually discussed it,’ said one of the nurses, ‘because I’ve seen psychologists, psychiatric nurses and auxiliary nurses who actually are friends with patients’.

Some nurses expressed surprise that their colleagues, whom they regarded as highly competent, chose to be Facebook friends with patients. One of the nurses who had not accepted patients’ friend requests said the following:

‘I think this applies to all of us, but maybe I’ve thought now and then that a psychologist should have an even better understanding of how things can turn out, or what it will do to the patient and relations between them. But I think the psychologist had had this patient over the years, so it’s almost like [I] think that there are some patients you have a lifelong relationship with. So it could be that.’

Some nurses mentioned the existence of general recommendations and rules, while others had no knowledge of any such rules or prohibitions. One nurse, who had accepted friend requests from several patients, said the following:

‘Strictly speaking, one or another guideline [has come out]. I don’t remember if it was from the Norwegian Nurses Organisation in general. But in any case, it said that nurses aren’t supposed to be friends with patients.’

Reasons for accepting or declining friend requests

All eight of the nurses who used Facebook had received friend requests from patients. The friend requests elicited different responses from the nurses. Five nurses chose to accept some friend requests from patients, while three nurses declined patients’ friend requests. For some nurses, it was a relief not to receive a lot of requests.

One nurse who had accepted a friend request explained that he had many patients who wanted to be friends on Facebook. He had let most of the requests go unanswered, but there was one he had decided to accept. In his explanation, the nurse emphasised that they had had many ‘good experiences together’ and that they ‘were on the same wavelength in lots of areas’.

Furthermore, the nurse assessed the specific patient to be ‘higher functioning’ than other patients. He feared that other patients might begin to ‘open up more and perhaps talk about their problems and want help with this and that’.

One of the other nurses who accepted friend requests from patients also stressed the positive contact she had with those patients.

A nurse who had accepted friend requests from patients explained that she tells the patients before she adds them as a friend that she thinks it is nice that they want to be friends on Facebook – but that if she receives ‘a chat message there about how life is difficult or something similar’, then she will block them. For her, Facebook is something she does in her spare time, so she does not want to sit and interpret what the patients are really thinking.

Some nurses felt reluctant to decline their patients’ friend requests.

One nurse who did not accept any patients’ friend requests described how she had responded when she received a friend request from a patient with whom she had had an especially positive and trusting relationship:

‘Then I was advised that I could block her. And I was also advised to ignore it. I didn’t follow any of that advice. Because if you are blocked, you are completely rejected, you can’t look that person up on Facebook, and it’s a real rejection. I didn’t want to do that to her. And to ignore her request would be hurtful, too, so I chose not to do that either. But what I did do was to write an email to her and explain that we had a sort of common understanding that we would not be Facebook friends with patients, former patients, and that this was just a common rule we had.’

She continued: ‘And then I wrote that I hoped she was doing well, hoped she understood that it was the policy in our department, that that’s the way it was, then I wished her a good autumn or something like that. So I tried to handle it politely, which felt right to me, because [I] run into her in town […], so in a way [...], yes, it’s showing the patients respect.’

Some nurses felt reluctant to decline their patients’ friend requests, and they found it helpful to refer to common rules. Others avoided directly declining such requests by letting them go unanswered.

Impersonal Facebook friendship

Three of the nurses who had patients as Facebook friends said that they used Facebook in a way that did not involve close personal contact. They described this with statements such as: ‘Whatever I share, I’m happy to share with everyone’.

A nurse posted photos of herself and her children on Facebook but commented that she did not share anything that could not appear in the local newspaper – it was ‘not a secret’.

Some nurses restricted what they posted on Facebook since their relationships with different people varied, including with patients. They felt it was both simpler and more appropriate to share information in person with each individual.

The information that patients chose to share on Facebook affected the nurses’ perception of the Facebook friendship. When a patient sent a photo of her children to one of the nurses, the nurse thought it was completely inappropriate to ‘have her children in my living room’.

The information that patients chose to share on Facebook affected the nurses’ perception of the Facebook friendship.

Another nurse described how she used Facebook to ‘educational effect’ in one case. The nurse said that she and her patient who was a Facebook friend had looked together at how the patient was using Facebook:

Nurse: ‘We talk a little about what we’re trying to communicate where, and as in her case, she could be on Facebook and […] which statuses here do you think are fun to read and do you feel puts you in a good mood?’

Interview: ‘I see, so you sit beside her and look at Facebook?’

Nurse: ‘Yes. And then it’s a little odd that there are no Facebook profiles resembling hers that she likes to read. So it can be a bit like that. What you communicate and the impression you give, you don’t need to show your pain and disappointment or the indignities you’ve suffered all the time. It’s sort of like that. So it’s now become sort of positive that she uses it much more to share her interests and what she has achieved. Look at the difference in the likes and comments [based on what the patient has written on Facebook].’

Some nurses gave feedback to the patients who were Facebook friends by liking or commenting on their posts. However, some nurses felt this entailed so little contact that, in the words of one nurse, ‘it’s really just nonsense that we’re friends on Facebook’.

Thus, impersonal and limited contact on Facebook could be used both as an argument against and as an argument for the acceptability of being friends with patients on Facebook.

Discussion

According to new ethical guidelines, nurses are expected to exercise digital common sense (8). However, it is difficult to know what constitutes good judgment regarding digital media without more specific recommendations.

The concept of digital common sense has its origins in the digital revolution in compulsory education (18) and is defined as the ability to acquire important information, evaluate media content and think critically (19–20).

For nurses, this can be a matter of how they relate to their own and their patients’ Facebook content, as well as critically reflecting on professional boundaries on social media. This study and other studies (3–6) reveal great variation in both attitudes to and experiences with social media in general, and with Facebook in particular.

Digital common sense and professional boundaries

Like other ethical and professional dilemmas, digital common sense will be subject to the individual practitioner’s assessment, and there is no guarantee that everyone will demonstrate good judgment.

Nurses’ assessments of specific issues will differ, such as in this study which reveals different views on whether nurses should accept Facebook friend requests from patients.

Health professionals with a negative view of having contact with patients on Facebook emphasised the challenges related to professional boundaries and privacy protection (5, 14). Scepticism about being Facebook friends with patients is reflected in the nurses in this study, which explored the problem of how Facebook friendships with patients can blur the line between work and private life. Facebook friendships can be regarded as a mixing of roles (13) – a situation where the nurse and patients take on multiple roles in relation to each other.

Nurses can have different perceptions of their own role and the patients’ roles on Facebook. Some nurses in this study expected patients not to burden them with their distress and need for comforting on Facebook.

Sometimes nurses accepted a patient’s friend request on the condition that the patient only expected to have superficial contact with them on Facebook. Such assessments of individual patients may be recommended (13), but they can also result in differential treatment that can affect the nurse’s professional relationship with that patient and possibly with other patients.

By the same token, declining a friend request can have a negative impact on the professional relationship (21). Rejection on social media can be particularly difficult in mental health care, where the therapeutic relationship between nurses and patients is essential for the ability to provide care and support (12).

Advice on what to do and not do

The professional guidelines on digital common sense allow for various assessments of what constitutes good judgment in different situations. Many people may find it difficult to assess what is appropriate use of social media (7), which may be a source of conflict among colleagues (22).

As this study shows, colleagues in the same field can have quite different opinions of how to behave on social media platforms such as Facebook. Some choose not to use Facebook precisely because of the discomfort that comes from having to decline patients’ friend requests. Such challenges can also lead nursing students to choose not to have a Facebook account (23).

Specific recommendations on digital common sense can be a support for nurses as they make decisions regarding digital and social media – such as in this study where a nurse referred to common departmental policy when she declined a patient’s friend request.

Facebook friendships between nurses and patients are often not recommended. It is described as ‘best practice’ for nurses to avoid being Facebook friends with patients or families with whom they have a professional relationship (24).

Although nurses may be tempted to maintain contact with patients through Facebook after discharge (25), social media platforms are covered by laws and general ethical guidelines that recommend declining patients’ friend requests (26).

Nurses can end up in an unfortunate situation if they breach their duty of confidentiality with likes or comments.

A widespread perception is that privacy settings on social media are adequate, but this is regarded as a myth (24). Nurses can end up in an unfortunate situation if they breach their duty of confidentiality with likes or comments exchanged between them and patients who are Facebook friends.

Confidentiality, privacy protection and professional boundaries are overarching concerns for nurses, regardless of the context. As such, overstepping boundaries on social media is more an example of one of the many contexts in which ethical and legal boundaries are practised than an example of a cause of a breach of professionalism (12, 27).

Context independence and ongoing technological advancement can be good reasons for strongly encouraging digital common sense rather than tying instructions to specific digital solutions.

The foundation for exercising digital common sense must be established during the nursing education, but ethical reflection on digital dilemmas in nursing practice should also be facilitated.

Limitations of the study

The use of social media changes over time. With regard to Facebook, the changes in the past decade have centred around how the platform is used. The trend has moved in the direction of liking, commenting and sharing less (28).

This can have an impact on whether nurses view Facebook as a part of their private life and whether being Facebook friends with patients could test professional boundaries.

Facebook is the most used social media platform across all age groups, but other platforms are growing (1). Given that Facebook is more widely used now than it was when the study was conducted, nurses and patients are now more likely to find each other on Facebook.

However, the increased emphasis on privacy protection in recent decades may have resulted in a greater focus on protecting personal information on social media. If nurses, for example, restrict access to their Facebook profile, patients will have a harder time finding them.

Dilemmas regarding contact with patients on Facebook had already surfaced in 2013 and 2014 when the study was conducted. Patterns of use change over time, but nurses must still take a position on these dilemmas – both on Facebook and on other social media platforms.

Social media was created to make people more accessible to each other, and nurses must decide how they will handle the professional boundaries between themselves and their patients in the digital sphere.

Conclusion

This study shows that nurses make different, and sometimes conflicting, assessments of having contact with patients on Facebook. Digital common sense depends on knowledge about and reflection on how social media can test professional boundaries and affect the nurse-patient relationship.

As such, digital common sense can be linked to the various learning outcomes that apply for the competence area of technology and digital competence in the nursing education (29).

Digital media are an important part of everyday life for both nurses and patients. In the future, it will be necessary to more closely examine how contact, as well as the absence of contact, on these platforms can affect relations between nurses and patients.

References

1. Medienorge. Bruk av sosiale medier en gjennomsnittsdag. Bergen: Medienorge; 2020. Available at: http://medienorge.uib.no/statistikk/medium/ikt/412 (downloaded 06.06.2020)

2. Ipsos. Ipsos SoMe-tracker Q1'20. Oslo: Ipsos; 2020. Available at: https://www.ipsos.com/nb-no/ipsos-some-tracker-q120 (downloaded 06.06.2020).

3. Lefebvre C, McKinney K, Glass C, Cline D, Franasiak R, Husain I, et al. Social media usage among nurses: Perceptions and practices. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2020;50(3):135–41.

4. Piscotty R, Martindell E, Karim M. Nurses' self-reported use of social media and mobile devices in the work setting. On-Line Journal of Nursing Informatics. 2016;20(1).

5. Peluchette JV, Karl KA, Coustasse A. Physicians, patients, and Facebook: Could you? Would you? Should you? Health Mark Q. 2016;33(2):112–26.

6. Bosslet GT, Torke AM, Hickman SE, Terry CL, Helft PR. The patient–doctor relationship and online social networks: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1168–74.

7. Haugen K, Johansen H. Digital dømmekraft er et tema du bør diskutere med dine kolleger. Sykepleien. 2019;107(77356):(e-77356). DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleiens.2019.77356

8. Norsk Sykepleierforbund (NSF). Yrkesetiske retningslinjer for sykepleiere. Oslo: NSF; 2019. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/vis-artikkel/2193841/17036/Yrkesetiske-retningslinjer-for-sykepleiere (downloaded 02.01.2020).

9. Aarseth S. Leger og sosiale medier. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2019;13. DOI: 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0448

10. Helsedirektoratet. Veileder i bruk av sosiale medier i helse-, omsorgs- og sosialsektoren. Oslo: Direktoratet for e-helse; 2019. Available at: file:///C:/Users/sigfla/Downloads/Veileder-sosiale-medier-versjon-2%200.pdf (downloaded 17.12.2020).

11. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 64 om helsepersonell m.v. (helsepersonelloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64 (downloaded 02.01.2020).

12. Ryan GS. International perspectives on social media guidance for nurses: a content analysis. Nurs Manage. 2016;23:28–34.

13. Zur O, Walker A. To accept or not to accept? How to respond when clients send «friend request» to their psychotherapists or counselors on Facebook, Linkedin, Twitter, or other social networking sites. Zur Institute; 2011. Available at: https://www.zurinstitute.com/socialnetworking/ (downloaded 02.01.2020).

14. Green J. Nurses’ online behaviour: lessons for the nursing profession. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53(3):355–67.

15. Basevi R, Reid D, Godbold R. Ethical guidelines and the use of social media and text messaging in health care: a review of literature. NZJ Physiother. 2014;42(2):68–80.

16. Unhjem JV. Nurses' experiences of professional boundaries in mental health care : a multisite qualitative study using source triangulation [Doctor's thesis]. Oslo: University of Oslo, Det medisinske fakultet, Institutt for helse og samfunn; 2019. Available at: https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/67680 (downloaded 02.01.2020).

17. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101.

18. Bjørndal KEW. Digital dømmekraft: utprøving og empirisk analyse av et undervisningsopplegg for ungdomstrinnet, inspirert av filosofering med barn-bevegelsen, med formål og å fremme kritisk internettbruk. (Doktoravhandling.). Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø, Fakultet for humaniora, samfunnsvitenskap og lærerutdanning; 2012. Available at: https://munin.uit.no/handle/10037/4365 (downloaded 02.01.2020).

19. Meld. St. 17 (2006–2007). Eit informasjonssamfunn for alle. Oslo: Det kongelige fornyings- og administrasjonsdepartementet; 2006. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-17-2006-2007-/id441497/ (downloaded 02.01.2020).

20. Engen BK, Giæver TH, Mifsud L. Digital dømmekraft. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 2017.

21. Sabin JE, Harland JC. Professional ethics for digital age psychiatry: Boundaries, privacy, and communication. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2017;19:55.

22. Miller LA. Social media savvy: risk versus benefit. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 2018;32(3):206–8.

23. Barnable A, Cunning G, Parcon M. Nursing students’ perceptions of confidentiality, accountability, and e-professionalism in relation to Facebook. Nurse Educ. 2018;43(1):28–31.

24. Westrick SJ. Nursing students’ use of electronic and social media: Law, ethics, and e-professionalism. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2016;37(1):16–22.

25. Ashton KS. Teaching nursing students about terminating professional relationships, boundaries, and social media. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;37:170–2.

26. Becker F. Etiske aspekter ved lege-pasient-relasjoner i nye medier. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2011;17(131):1677–9. Available at: https://tidsskriftet.no/2011/09/medisinsk-etikk/etiske-aspekter-ved-lege-pasient-relasjoner-i-nye-medier (downloaded 02.01.2020).

27. Brandtzæg PB, Gillund L, Krokan A, Kvalnes Ø, Meling AT, Wessel-Aas J. Sosiale medier i all offentlighet: lytte, dele, delta. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget, 2011.

28. Deloitte. Deloittes medievaneundersøkelse 2018. Oslo: Deloitte; 2018. Available at: https://info.deloitte.no/rs/777-LHW-455/images/Deloittes_Medievaneundersøkelse_2018.pdf (downloaded 06.06.2020).

29. Kunnskapsdepartementet. Forskrift 15. mars 2019 nr. 412 om nasjonal retningslinje for sykepleierutdanning. 2019. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2019-03-15-412 (downloaded 15.04.2020).

Comments