Is it acceptable to be asked about alcohol habits when admitted to a somatic hospital ward?

The patients accepted being asked about their alcohol habits and being referred to an alcohol and drug counsellor. The under-60s were more positive.

Background: Excessive consumption of alcohol is an important cause of increased morbidity and mortality. When a patient’s alcohol consumption is a potential contributory factor to poor health, Norwegian hospitals have a duty to identify this and take the necessary steps. Understanding the patients’ values, preferences and experiences is key to evidence-based practice, combined with knowledge about the effects of treatment and the clinicians’ experiential knowledge.

Objective: To explore what patients with no known history of substance use problems felt about being referred to and having a conversation with an alcohol and drug counsellor.

Method: Since 2008, Stavanger University Hospital (SUH) has offered the services of a drug and alcohol liaison team, currently consisting of a registered nurse and a social worker. The team’s objective is to improve the quality of treatment on somatic wards by identifying underlying substance use problems and offering appropriate help. Patients who had talked to an alcohol and drug counsellor at SUH and who had no previous history of substance use problems were invited to take part in a telephone interview one week after they were admitted to hospital.

Results: The majority of the study participants took a positive view on having their alcohol habits addressed. Patients under 60 years of age were generally more positive, and they saw a clearer connection between their alcohol habits and their own health than patients who were 60 years of age or older. Ninety-three per cent of the participants felt that their conversation with the alcohol and drug counsellor had focused on their own health and life situation to some extent or to a great extent, while 54 per cent believed that alcohol habits would be addressed during later consultations with their general practitioner.

Conclusion: The study shows that patients with no previous history of substance use problems generally accepted that their alcohol habits were addressed and that they were g referred to an alcohol and drug counsellor. We need more knowledge about how the subject of alcohol can be raised in ways that are meaningful to the individual patient, and about the patients’ perspective on interaction between general practitioners and the specialist health service.

Excessive consumption of alcohol is an important cause of increased morbidity and mortality (1). From a public health perspective, and from the perspective of the individual patient, it is therefore important that the health services are aware of alcohol as a possible contributor to – or complicating factor for – patients’ health problems.

In Norway, alcohol consumption per person over 15 years of age increased by almost 40 per cent between the early 90s and 2010, from approximately 5 litres of pure alcohol. Consumption has now dropped again to its current level of just over 6 litres (2, 3). In a lifespan perspective, 10–20 per cent will experience injuries caused by substance use, most commonly alcohol (2).

In a lifespan perspective, 10–20 per cent will experience injuries caused by substance use, most commonly alcohol.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the number of alcohol-related hospital admissions increased by 44 per cent, calculated per 100 000 inhabitants (4). In Norway and the rest of the Western world, the greatest increase in alcohol consumption is found among the so-called baby boomers, the large cohorts who were born in the two decades following the second world war (5).

Furthermore, physiological changes, ailments and the use of medication make the elderly more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol use (6).

Procedures for identifying substance abuse have been established

In 2013, the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services issued a commissioning document to Norwegian hospitals which accentuated the need for somatic wards to implement systems that would identify patients with underlying substance use problems and refer them for interdisciplinary specialist treatment if appropriate (7).

In parallel, we saw the setting up of a national competence service for interdisciplinary specialised treatment of substance use problems (NK-TSB) to assist with developing such initiatives, among other things. Similar measures have been introduced in other countries, amongst them the UK, where routine screening is recommended (8).

However, it has been challenging to establish such routines as a part of normal clinical practice, and it has been difficult to document the effect in research (9, 10). Researchers at Sørlandet Hospital in Kristiansand found that compared to smokers, a significantly lower proportion of patients with unhealthy or harmful alcohol consumption were given advice on behaviour change while in hospital (11).

Nevertheless, there is reason to claim that talking to patients about their alcohol habits during a stay in hospital may be effective if the patient understands the connection between the health problem and the intervention (12).

What do patients think about having their substance use addressed?

It is likely that many patients with serious and complex substance use problems wish to receive help when they are admitted to hospital (13). However, with respect to patients who have never previously had their alcohol habits reviewed, we have little knowledge of what they think about being ‘identified’ and offered assistance while in hospital (14).

Evidence-based practice builds on research into the effects of treatment, clinicians’ experiential knowledge, and the patients’ values and preferences (15). The patients’ acceptance of being asked about their alcohol habits is a key issue, because healthcare personnel have been found to assume a lack of patient acceptance, which forms a significant barrier to asking (16, 17).

It has also been shown in population surveys that people whose consumption of alcohol is unhealthy or harmful are more negatively inclined to having their alcohol habits addressed by the health service (18, 19).

Internationally, the assessment is generally conducted by registered nurses in accident and emergency departments. Only a few qualitative studies have been conducted, and these have primarily identified barriers, whether of a personal nature or related to systems or patients (17, 20, 21).

The study’s objective

The objective of our study was to explore what patients felt about having their alcohol habits addressed for the first the time on a hospital somatic ward, and what they felt about the help they received. We also explored whether there were systematic differences between the perceptions of different age groups.

Method

The survey was conducted at Stavanger University Hospital (SUH) in the period between 1 December 2015 and 1 June 2017. Patients were recruited by the drug and alcohol liaison team in their day-to-day work.

The inclusion criteria were: older than 18 years of age, no previous history or treatment of an alcohol problem, ability to communicate in one of the Scandinavian languages or in English, normal cognitive status and clinically non-intoxicated. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were asked by the alcohol and drug counsellor to give their consent during their first session.

The drug and alcohol liaison team at Stavanger University Hospital

In 2008, SUH was the first hospital in Norway to start a project that involved providing the services of a dedicated alcohol and drug counsellor in the Emergency Department’s observation and treatment ward, the Infectious Medicine Department and the Gastroenterological Department. The counselling service is now a permanent feature on all somatic wards.

The objective is early intervention in cases of substance-related health problems. This is achieved by identifying and intervening in cases of unhealthy or harmful substance use, thereby offering better treatment for the ailment or injury for which the patient was admitted.

A referral is sent by a ward nurse or doctor whenever a disease, condition or finding suggests that alcohol habits may be an influencing factor, whenever emergency incidents are combined with intoxication, and whenever a patient’s family raises a concern. The drug and alcohol liaison team also provides an information service for departments and disciplines.

The offer of one-on-one conversations in private involves reviewing the patient’s life situation, alcohol habits and use of other substances and providing help for patients to change their alcohol habits. The conversations are generally conducted while the patient is in hospital, and sometimes shortly after discharge.

The method is based on motivational interviewing (MI), with all advice and information being linked to the patient’s health problem (22). The general practitioner receives a summary of the conversation or conversations, and if required, the patient is referred to a municipal programme or to the interdisciplinary specialised treatment service for substance use.

Target groups for the drug and alcohol liaison team

The drug and alcohol liaison team has two target groups. The primary group consists of patients with health problems that may be alcohol related, but who have no previous substance use diagnosis and who have never previously had their alcohol habits addressed. The secondary group consists of patients with known and serious substance-related health problems, often with a history of multiple hospital admissions related to substance use problems.

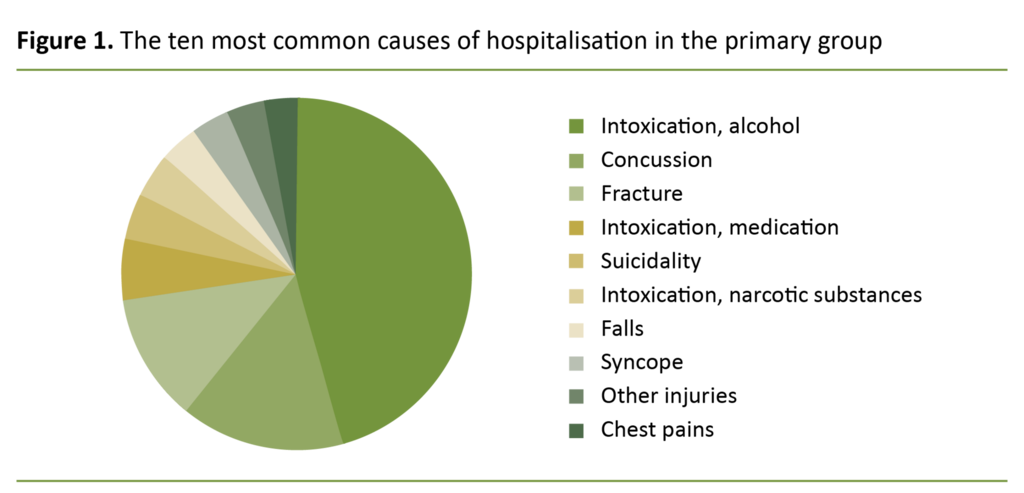

Figure 1 shows the ten most common causes of hospitalisation in the primary group. The differentiation between a primary and a secondary group was introduced in order to increase awareness of ‘the invisible’ problems caused by substance use, particularly alcohol.

A qualitative study had shown that general practitioners were particularly keen to receive feedback relating to previously unidentified alcohol problems, as they knew there were some patients with alcohol problems they were unaware of (23).

Because there is insufficient evidence to establish which screening strategies are best suited for what patients, SUH chose a strategy based on clinical relevance rather than opting for general screening of all patients (14, 24). In the course of the study period, 1026 patients were referred to see a counsellor. Of these, 301 patients were in the primary group.

Details about the overall material during the study period were obtained from a time-limited quality registry associated with the drug and alcohol liaison team. We compared the participants’ background information to similar background information for everyone in the primary group during the study period.

The questionnaire and the interview

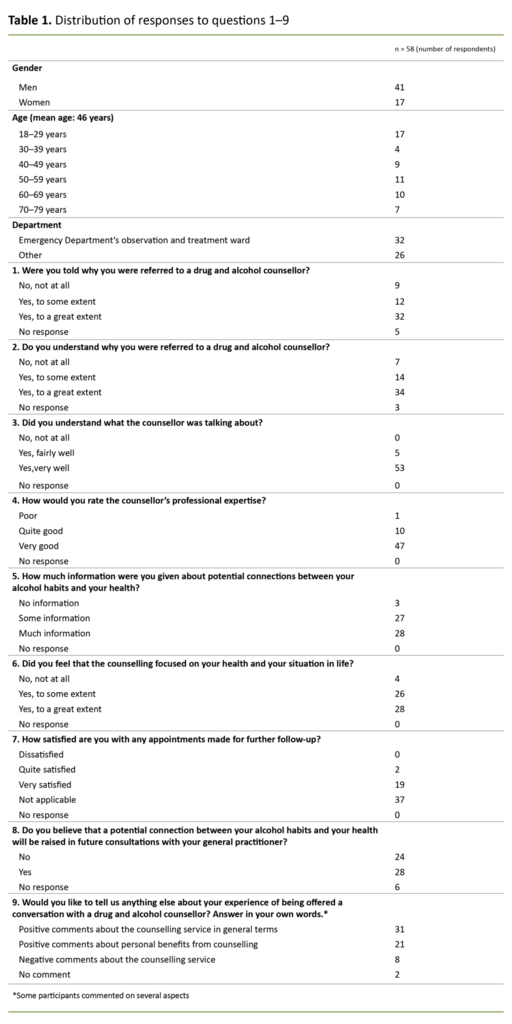

The questionnaire that was used during the interview had been specifically designed for the purpose of the study. The questions are listed in table 1, along with the total number of answers in each response category.

There were eight questions with graded response options and one open-ended question: ‘Would you like to tell us anything else about your experience of being offered a conversation with an alcohol and drug counsellor?’

Registered nurses as well as patients may consider it a sensitive matter for the healthcare service to address unhealthy alcohol habits and introduce interventions in identified cases. Our questions were therefore phrased so as to shed light on important aspects that might make the intervention acceptable to the patients.

The questions address whether patients received the required information about the counselling initiative, whether they felt it was relevant and adapted to their own situation, whether it was well executed, and whether they perceived the counselling service to be an integral part of the hospital’s overall provision of healthcare.

Patients who gave their consent to taking part in the study were interviewed over the telephone by a research assistant one week after they were admitted to hospital. Patients who did not answer the phone were called a total of three times. The correlation between the participants’ responses and their age has been analysed using chi-squared tests.

We used a chi-squared test to investigate whether there were significant differences between the age groups. If the test result was significant, we tested pairs of age groups. The analyses were conducted in SPSS 24.

Ethical approval

The research project was approved by the Data Protection Officer at SUS.

Results

In the course of the study period, a total of 1026 referrals were sent to the liaison team. Of these, 301 patients were in the primary group and over 18 years of age. In the primary group as a whole, the percentage of women was 37, and 60 per cent were in employment. In the secondary group (725 patients), 31 per cent were women and 18 per cent were in employment.

The counsellors conducted at least one conversation with 182 patients, of whom half (91 patients) gave their consent to taking part in the study. Of these 91 patients, 58 responded while 12 patients withdrew their consent and 21 patients did not answer when the research assistant phoned them.

Based on the number who gave their consent, this gives a response rate of 64. Out of the 301 patients in the primary group during the study period, 119 did not talk to a counsellor. This was because the patient was not present (they had either been discharged or left the ward of their own accord), because of the patient’s condition (serious somatic illness, undiagnosed mental condition, intoxication or cognitive impairment) or because of language problems.

Ninety-one patients who did talk to a counsellor were either not invited to take part or did not give their consent. Most of these were not invited because they appeared to be too ill, cognitively impaired or clinically intoxicated during the conversation.

Unfortunately, no record was made of how many patients were not asked because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and how many were asked but did not give their consent to participate.

The participants’ gender distribution

No identifiable information was recorded for any of the patients in the primary group. Consequently, some study participants were included in both groups when we compared them to all patients in the complete primary group who had talked to an alcohol and drug counsellor.

The gender distribution among the study participants was relatively similar to the gender distribution among patients in the full primary group, with 29 per cent women in the study participants and 34 per cent women in the primary group.

Forty-five per cent of the study participants had been admitted to wards other than the Emergency Department’s observation and treatment ward, while this percentage was somewhat lower (36 per cent) in the full primary group. There were no clear age differences between the full primary group and the study participants.

Participants took a positive attitude to their referral and conversation

Completely positive responses (‘yes’, ‘to a great extent’ or ‘very well’) made up the largest percentage of answers to questions that concerned the patients’ perception of their referral to and conversation with the counsellor. However, answers were more or less evenly distributed between completely positive and partly positive responses to questions about the connection between alcohol habits and the patient’s own health and life situation (table 1).

When asked about further follow-up, two respondents were quite satisfied and 19 were very satisfied, while the remaining 37 answered that the question was not applicable to them. Twenty-eight believed that the connection between alcohol habits and their own health would also be raised in future consultations with their general practitioner. This was a higher number than the 21 respondents (question 7) who had in fact been given appointments for further follow-up.

The majority understood why they had been referred

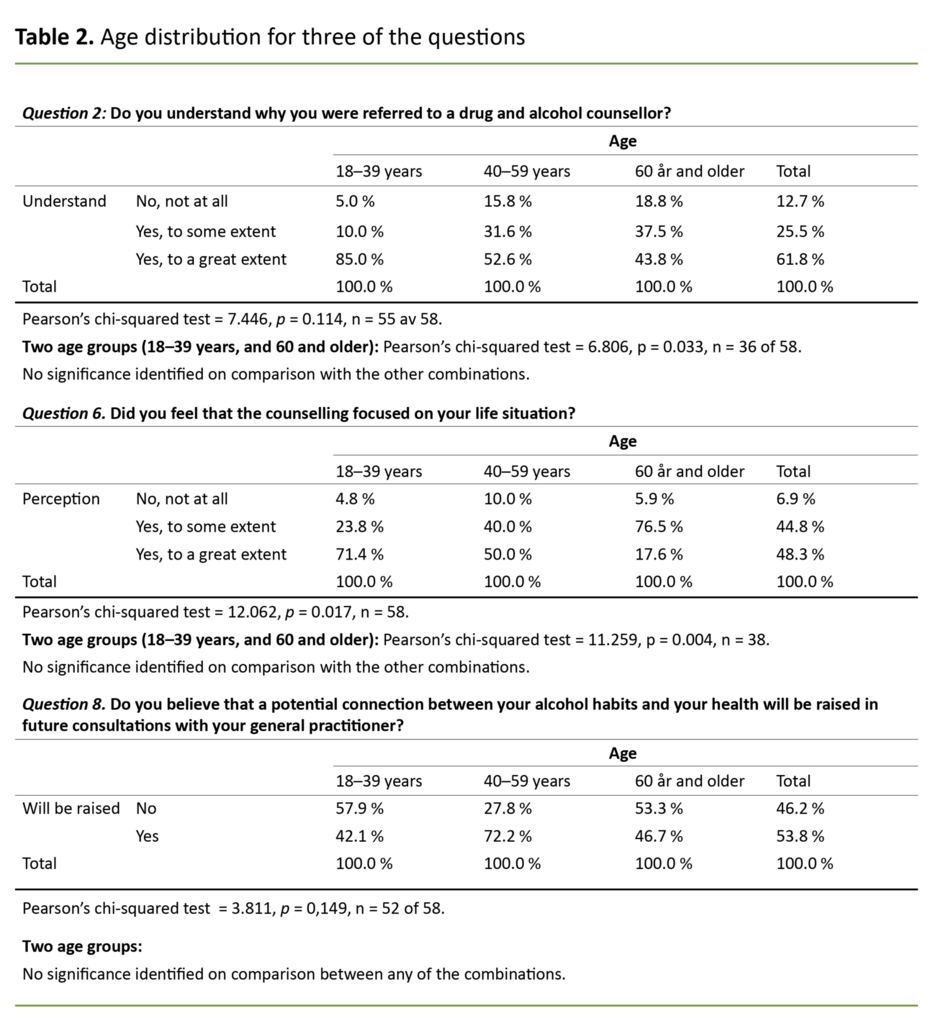

Table 2 presents the answers to questions 2, 6 and 8 in greater detail. These questions particularly addressed the patient’s own understanding of the connection between their alcohol habits and their health. Overall, a large majority of the patients answered that they understood, to some or a great extent, why they had been referred (87.3 per cent) (table 2).

Overall, a large majority of the patients answered that they understood, to some or a great extent, why they had been referred.

As many as 93.1 per cent of the participants felt that the conversation focused to some or a great extent on their own health and life situation (table 2). A clear majority of patients in the 40–59 age group (72.2 per cent) believed that alcohol habits would be raised in future consultations with their general practitioner, while this applied to a minority of patients who were younger than 40 or older than 60 (table 3).

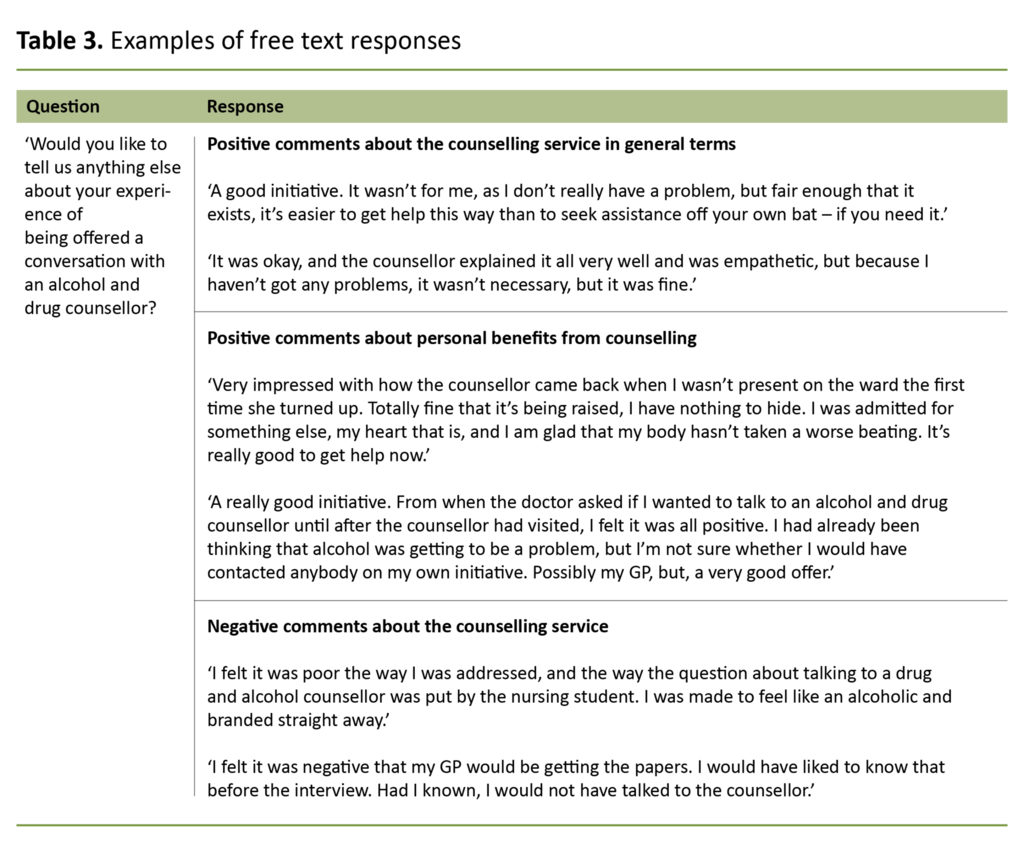

We saw from the free text responses that more than 50 per cent of the positive comments were concerned with the counselling service in general, while less than 50 per cent of these comments were concerned with the patient’s personal experience of benefitting from counselling (see table 3 for examples). Eight patients described a negative perception of how the intervention was conducted or the substance of the service.

Younger respondents expressed a greater level of understanding than older respondents

We have studied correlations between age and the patients’ responses to being asked if they understood why they had been referred to an alcohol and drug counsellor (question 2), whether they felt that the counselling focused on their own health and life situation (question 6), and potential follow-up by their general practitioner (question 8).

These are key questions that concern the patients’ perception of the identification and intervention processes as well as their expectation of a follow-up with their general practitioner. Patients in the 18–39 age group expressed significantly greater understanding of being referred for counselling than patients over the age of 60.

The over-60s were less inclined than the youngest respondents (18–39 years) to feel that the conversation focused on their own life situation. There were no significant differences between the 18–39 and 40–59 age groups with respect to questions 2 and 6. We found no significant differences between age groups with respect to question 8.

Discussion

The study’s objective was to examine what patients on somatic wards felt about having their alcohol habits addressed for the first time while in hospital, and what they felt about their referral to and conversation with the counsellor.

The results showed that a great majority of the patients understood the reason for referral, and that they felt their conversation with the counsellor was relevant to their own health, to some or a great extent.

Significantly fewer patients over the age of 60 took a positive view of the referral and of the connection between their alcohol habits and their health.

There were no significant gender differences, but significantly fewer patients over the age of 60 took a positive view of the referral and of the connection between their alcohol habits and their health.

The study was conducted as part of normal clinical practice at SUS. This means that the patients were identified by registered nurses or doctors either on the emergency observation and treatment ward or on an inpatient ward, and that they were given advice and guidance by counsellors who routinely provide this service.

The strengths and weaknesses of the study

It is a strength that the study is closely linked to practice and examines clinical work which is routinely carried out. However, it is an important weakness that we failed to record how many of the 91 patients did not give their consent to participate, declined the invitation, or were not asked because they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Furthermore, we have no information about the participants’ use of alcohol. The survey was completed by sixty-four per cent of the 91 included patients.

There were no age or gender differences between the study participants and the remainder of the primary group. This suggests that our material is representative for a large proportion of patients who are admitted to somatic wards with no pervious history of substance use diagnoses, but whose condition is affected by alcohol, either directly or indirectly. This is one of the study’s strengths.

Research on brief alcohol interventions in hospital is normally conducted in emergency departments, and surveys as well as interventions are frequently conducted by researchers rather than by clinical staff, which weakens the external validity of these studies (9, 10). There is little difference between the study participants and the full primary group, which strengthens the relevance of our findings.

Many would have gone below the radar

Patients with alcohol-related health problems but no known history of substance use problems are difficult to recognise unless there is a direct and obvious connection with alcohol habits. Figure 1 shows that a large proportion of admissions are clearly alcohol-related. This is particularly the case with intoxication whereas the link is less obvious when it comes to many of the injuries.

Additionally, some patients in the primary group present with vague symptoms, such as a tendency of falling over, syncope and chest pain. We do not know what share of patients would have been asked about their alcohol habits if the drug and alcohol liaison team had not been in operation.

However, the primary group includes a considerably higher proportion of individuals (60 per cent) in employment or education than the secondary group (18 per cent), and there is clearly a larger proportion of women in the primary group (37 per cent) than in the secondary group (31 per cent).

These figures indicate that if no special measures had been in place to identify underlying substance use problems many of these patients would have been admitted and treated without a potential connection with alcohol being recognised and addressed.

Many believed that their alcohol habits would be raised in consultations with their general practitioner

Fifty per cent of participants responded that they believed the link between alcohol habits and health would be raised in consultations with their general practitioner. We consider this to be a high number based on what we know about alcohol conversations in the health service. However, we do not know whether they themselves intended to raise the subject or whether they believed that the doctor would do so.

Also, we do not know why 50 per cent did not think that alcohol habits would be a subject raised in consultations with their general practitioner. It may be because they felt the problem was a minor one, and that they therefore would need no further assistance. A considerable proportion of patients change their alcohol habits with no further help from the health service (25).

Fifty per cent of participants responded that they believed the link between alcohol habits and health would be raised in consultations with their general practitioner.

It may also be the case that the subject is associated with shame, and therefore difficult to talk about, or patients may prefer not to talk specifically to their general practitioner about it, or they may be uncertain whether the general practitioner is interested in the subject. Based on earlier research, we know that general practitioners consider any relevant hospital admission to form a good starting point for raising questions about alcohol habits (23).

Interestingly, there was a clear majority in the group between 40 and 59 years of age who thought that alcohol consumption would be raised in consultations with the general practitioner, while younger and older patients did not think it would be. We know that hospitalisation can be a clear incentive for patients to reflect on their own alcohol habits, even without receiving targeted assistance (12).

Patients over 60 years of age are more vulnerable to alcohol and are therefore at greater risk of harming their health by using alcohol, for reasons of physiological age changes, other medical conditions and use of medication (26).

It is therefore worrying that patients in this age group took the least positive view on having their alcohol habits addressed when in hospital.

Interventions related to alcohol consumption are particularly useful for the elderly

It has been suggested that more resources should be spent on brief alcohol interventions in the evenings, at night and over weekends (24, 27). This will strengthen the opportunity to help patients who are admitted with acute problems that are clearly alcohol-related (28).

However, a potential link with alcohol consumption will be less frequently picked up when patients present with vague clinical complaints such as dizzy spells, falls and repeated admissions for stomach pains or chest pains (28). These patients are often elderly and are admitted to general inpatient wards. A greater focus on brief alcohol interventions in emergency departments is unlikely to contribute to improving the health care they receive (24).

It is therefore a strength of the study that as many as 45 per cent of participants were recruited from other wards than the Emergency Department’s observation and treatment ward. Interventions based on the relevance of alcohol to the patient’s health problem appear to be particularly useful to the elderly, due to their reduced tolerance to alcohol, a greater number of relevant clinical issues and more frequent contact with the health service (26, 29).

The majority took a positive view on being referred to a counsellor

The free text responses show that most participants took a positive view on the offer of counselling, either in general or because they felt it was useful to them personally. Out of the eight negative comments, most referred to the way they had been identified and the way the referral had been conducted.

At the same time, many commented positively on the conversation they had with the counsellor. This suggests that there is a great need to normalise talking about alcohol habits as a standard part of procedures in relation to diagnostics, treatment and follow-up.

Alcohol habits may be associated with shame and are therefore difficult to talk about, and it may be particularly difficult for patients to initiate such a conversation of their own accord. As one of the quotes suggests (table 3), it is easy to be hurtful when raising such matters with the patient, or the subject may be raised in a situation that fails to protect the patient’s privacy and dignity (30).

At the same time, the serious nature of hospitalisation may provide a good basis for patients to review their thinking about possible connections between alcohol habits and health (12, 23).

Conclusion

Patients who are admitted to somatic hospital wards largely accept that their alcohol habits are being addressed, and that they are referred to an alcohol and drug counsellor as a part of their treatment. This is important knowledge as we seek to further develop the service. However, patients over 60 years of age are less positively inclined than younger patients towards having their alcohol habits addressed.

We need to normalise talking about alcohol habits as a standard part of procedures in relation to diagnostics, treatment and follow-up. We also need more clinically focused research in order to increase our knowledge about who needs further follow-up, and which interventions are effective.

References

1. Knudsen AK, Kinge JM, Skirbekk V, Vollset SE. Sykdomsbyrde i Norge 1990–2013. Resultater fra Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study 2013 (GBD 2013). Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 2016.

2. Folkehelseinstituttet. Folkehelserapporten 2014. Helsetilstanden i Norge. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet; 2014.

3. Statistisk sentralbyrå. Alkoholomsetning. Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå; 2018 [updated 06.03.2018, cited 21.03.2018]. Available at: https://www.ssb.no/varehandel-og-tjenesteyting/statistikker/alkohol

4. Rossow I. Challenges in an affluent society. Trends in alcohol consumption, harms and policy: Norway 1990–2010. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;27:449–63.

5. Barry KL, Blow FC. Drinking over the lifespan: focus on older adults. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):115–20.

6. Stewart D, McCambridge J. Alcohol complicates multimorbidity in older adults. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2019;365:14304.

7. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Oppdragsdokument 2013 Helse Vest RHF. Oslo: Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet; 2013.

8. NICE. Alcohol-use disorders: prevention. In: Excellence NIfHaC, ed. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2010.

9. McQueen J, Howe TE, Allan L, Mains D, Hardy V. Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(8):CD005191.

10. Drummond C, Deluca P, Coulton S, Bland M, Cassidy P, Crawford M, et al. The effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief intervention in emergency departments: a multicentre pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99463.

11. Vederhus JK, Rysstad O, Gallefoss F, Clausen T, Kristensen Ø. Kartlegging av alkoholbruk og røyking hos pasienter innlagt i medisinsk avdeling. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2015;135(14):1251–5.

12. Bischof G, Freyer-Adam J, Meyer C, John U, Rumpf HJ. Changes in drinking behavior among control group participants in early intervention studies targeting unhealthy alcohol use recruited in general hospitals and general practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1–2):81–8.

13. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. ‘It's been an experience, a life learning experience’: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296–303.

14. Makdissi R, Stewart SH. Care for hospitalized patients with unhealthy alcohol use: a narrative review. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2013;8(1):11.

15. Nortvedt MW, Jamtvedt GJS. Kunnskapsbasert praksis: engasjerer og provoserer. 2009;97(7):64–9.

16. Broyles LM, Rodriguez KL, Kraemer KL, Sevick MA, Price PA, Gordon AJ. A qualitative study of anticipated barriers and facilitators to the implementation of nurse-delivered alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for hospitalized patients in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:7.

17. Hellum R, Bjerregaard L, Nielsen AS. Factors influencing whether nurses talk to somatic patients about their alcohol consumption. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;33(4):415–36.

18. Nilsen P, Bendtsen P, McCambridge J, Karlsson N, Dalal K. When is it appropriate to address patients' alcohol consumption in health care-national survey of views of the general population in Sweden. Addict Behav. 2012;37(11):1211–6.

19. O'Donnell A, Abidi L, Brown J, Karlsson N, Nilsen P, Roback K, et al. Beliefs and attitudes about addressing alcohol consumption in health care: a population survey in England. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):391.

20. Groves P, Pick S, Davis P, Cloudesley R, Cooke R, Forsythe M, et al. Routine alcohol screening and brief interventions in general hospital in-patient wards: acceptability and barriers. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2010;17(1):55–71.

21. Derges J, Kidger J, Fox F, Campbell R, Kaner E, Hickman M. Alcohol screening and brief interventions for adults and young people in health and community-based settings: a qualitative systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):562.

22. Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):157–68.

23. Lid TG, Oppedal K, Pedersen B, Malterud K. Alcohol-related hospital admissions: Missed opportunities for follow up? A focus group study about general practitioners' experiences. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):531–6.

24. Roche AM, Freeman T, Skinner N. From data to evidence, to action: findings from a systematic review of hospital screening studies for high risk alcohol consumption. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83(1):1–14.

25. Willenbring ML. The past and future of research on treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(1–2):55.

26. Taylor C, Jones KA, Dening T. Detecting alcohol problems in older adults: can we do better? Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1755–66.

27. Parkinson K, Newbury-Birch D, Phillipson A, Hindmarch P, Kaner E, Stamp E, et al. Prevalence of alcohol related attendance at an inner city emergency department and its impact: a dual prospective and retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(3):187–93.

28. Huntley J, Blain C, Hood S, Touquet R. Improving detection of alcohol misuse in patients presenting to an accident and emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2001;18(2):99–104.

29. Rehm J, Manthey J. The role of standardized instruments in identifying older adults with alcohol problems. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(2):351–2.

30. Malterud K, Thesen J. When the helper humiliates the patient: a qualitative study about unintended intimidations. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(1):92–8.

Comments