How parents react when their child is overweight

When staff in the child health clinic and school health services tell parents that their child is overweight, many feel both a sense of shame and guilt.

Background: National clinical guidelines recommend individual assessment and counselling of overweight children and adolescents by the child health clinic and school health services.

Purpose: The purpose of the study was to acquire knowledge of how the parents of children aged 4 and 8−9 felt about being told that their child was overweight, and their experiences of participating in counselling sessions and activity groups.

Method: A qualitative study with individual interviews of six mothers. We analysed the interviews using text condensation inspired by Giorgi’s method.

Results: We found common features in parents’ experiences, which are summarized in four key topics: (1) Perception of criticism of the child and oneself, (2) A wish to protect the child, (3) Concern about the child’s experiences, and (4) Raising awareness and support for lifestyle changes.

Conclusion: Parents not only feel that the child’s weight gain is criticism of the child, but also a criticism that they have failed as parents. Having an overweight child may be perceived as shameful. Counselling sessions organized by the school health services provided good support but parents do not want their child to take part in order to protect him/her. The parents who did not wish to participate in the activities offered found it problematic that the child might be associated with being overweight. Those who participated in the activities offered felt it was very helpful to be with others in the same situation. They emphasized the positive aspects of children and parents taking part in fun activities together.

The child health clinic and school health services have a long tradition of carrying out height and weight measurements during health check-ups of children and adolescents. Such check-ups have provided vital information and an overview of Norwegian children’s weight development. In 1998 however, the number of routine measurements of height and weight was reduced, and replaced by measurements undertaken when the public health nurse or doctor felt this was required on medical grounds (1). The reasons for the change in practice include a lack of documentation on the effect and usefulness of screening for height and weight, as well as concern that a focus on weight might trigger eating disorders (2).

More children and adolescents are overweight

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents has increased in recent decades and is described today as one of the greatest challenges in public health work (2–4). In Norway, 15 per cent of boys and 18 per cent of girls aged 4–16 are either overweight or obese (2). This increase places prevalence in Norway on a par with Great Britain and the other Nordic countries.

Overweight and obesity constitute a complex challenge (5) that can partly be explained by more sedentary lifestyles combined with changed eating habits (6). The increase in weight is found in all social classes but overweight is more prevalent in the lower socioeconomic groups (7). Such groups are associated with less physical activity and a lower intake of fruit and vegetables (8, 9). Based on the weight increase, the Norwegian health authorities have decided to reintroduce systematic measurements of weight and height. They also recommend measures to prevent and treat overweight and obesity (2, 6).

New guidelines

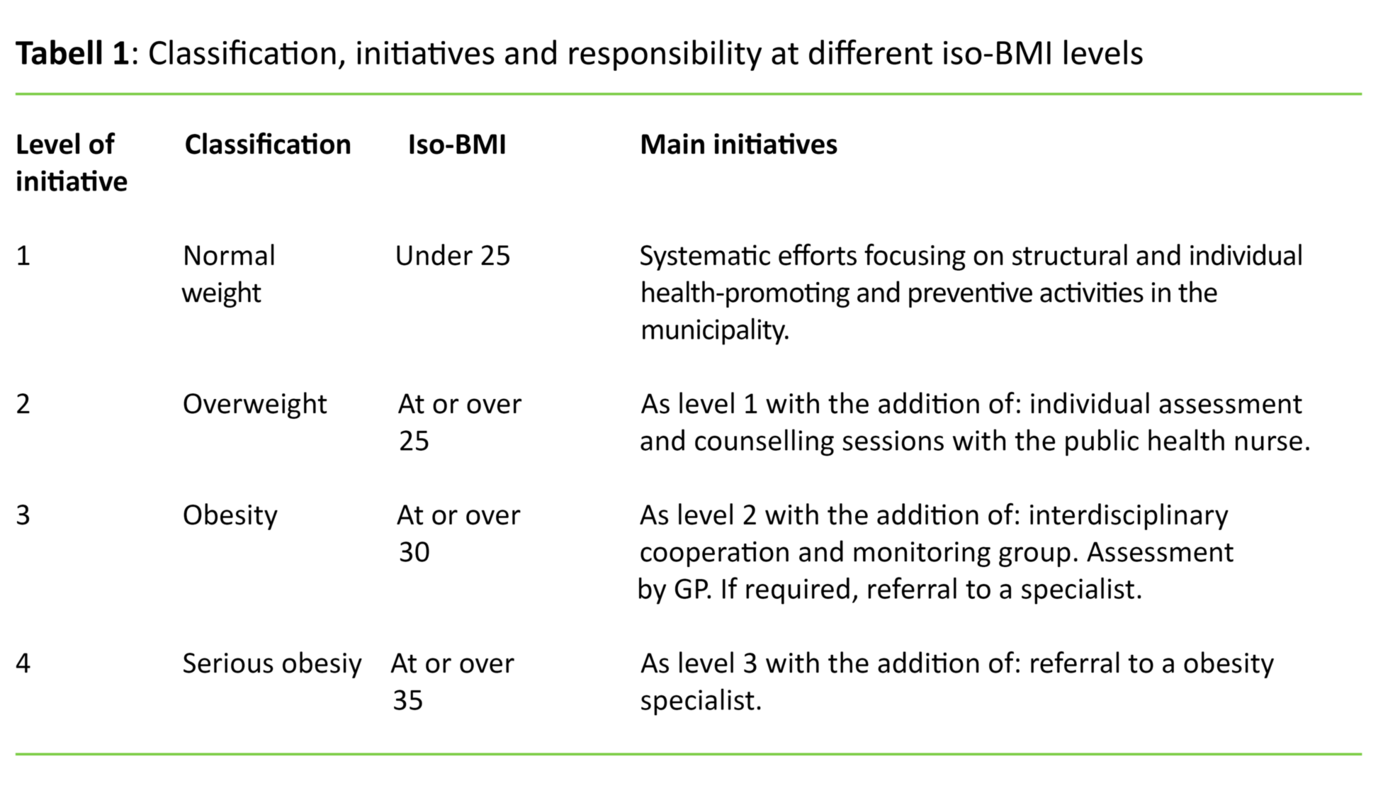

In 2010, the Norwegian Directorate of Health issued national clinical guidelines for the primary health service on the prevention, assessment and treatment of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents (6). The guidelines describe the responsibility of health professionals for health-promoting and preventive measures, assessment and treatment. The measures are categorized based on iso-BMI. BMI stands for Body Mass Index, which is calculated on the basis of weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. Iso-BMI is BMI adjusted for age and gender (10). The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified weight in four iso-BMI levels (6, p. 31), as presented in table 1.

An iso-BMI of 25 to 30 is defined as overweight (6), and the national clinical guidelines recommend individual assessment and counselling by the public health nurse for this group. Research shows that it is beneficial to initiate measures as early as possible since this can result in the child ‘outgrowing its overweight’ (6). In 2011, the Norwegian Directorate of Health also issued national clinical guidelines on measuring weight and height at the child health clinic and school health services designating the points in time recommended for measurement (2).

Project to motivate lifestyle changes

A project group from the child health clinic and school health services in a municipality in south-east Norway conducted a project in the 2011/2012 school year. The aim was to encourage overweight children and their parents to change their lifestyle. Based on the point of time recommended for height and weight measurements in the national clinical guidelines (2), the project group focused on children aged 4 and 8-9 (Year 3 of primary school).

One cohort of Year 3 pupils from two schools, and four-year-olds from one cohort linked to a public health nurse at the child health clinic were given the opportunity to participate in the project. The project group made a strategic choice of two primary schools in order to include children from different social classes. The public health nurse at the health centre or at the child’s school informed the parents if weight and height measurements showed an iso-BMI of 25 or above. The children and their parents were invited to participate in one of the two following initiatives:

- Three counselling sessions with a public health nurse and a physiotherapist at 0, 1 and 6 months after the measurement.

- Three counselling sessions with a public health nurse and a physiotherapist at 0, 1 and 6 months after the measurement. In addition, the offer of participation in an activity group in the evening, once a week for eight weeks.

The aim of the first counselling session was to map the eating and physical activity habits of the child and the family in order to motivate them to start a change process and help them to set goals (11). The public health nurse and the physiotherapist carried out two more sessions with the aim of providing further counselling as required.

If the family agreed to participate in the second initiative, both the child and the parents were expected to take part in the activity groups, which consisted of different games and physical activity. A physiotherapist was responsible for the groups and conducted them in cooperation with physiotherapy students. As part of the activities offered, there were also two group sessions on the topic of diet. The parents of nine Year 3 pupils agreed to take part in either the counselling sessions (initiative 1) or the counselling sessions plus the activity group (initiative 2), while none of the parents of the four-year-olds wished to take part.

The study and its purpose

In this study, we examine parents’ experiences with the project described above. In order to elicit parents’ perceptions, thoughts and experiences, we carried out a qualitative study with individual interviews (12). We wanted to acquire knowledge about how parents reacted to being told that their child was overweight, and how they felt about participating in counselling sessions and the activities offered. We applied to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data for permission and received approval to carry out our study.

Method

All nine parents who had participated in the project under the auspices of the child health clinic and school health services were asked to participate in the interview study. Six mothers agreed. Of the six who were interviewed, two participated in initiative 1 and four in initiative 2. Those who did not wish to participate said this was due to time constraints. We carried out the interviews in autumn 2012.

The first author of the article headed the child health clinic during the project period, but had not met the parents prior to the project. She was also project manager and carried out the semi-structured interviews. In order to be able to ask follow-up questions aimed at acquiring a deeper understanding, the interview format was flexible (12). We transcribed the interviews verbatim and analysed them with a view to eliciting the parents’ perceptions. Both authors read the interview texts in their entirety and we collaborated in the further analysis process to elicit further nuances in meaning. We used Giorgi’s method of text condensation and identified key topics in the results (13).

Results

A key finding in this study is that parents who were contacted by the public health nurse on account of the child’s overweight had conflicting emotions. They were concerned about protecting the child from the feeling that he/she was not good enough, whilst also recognizing the need for change in order to counter the further development of overweight. The findings shared common features that are summarized in four main topics: 1) Perception of criticism of the child and oneself, 2) A wish to protect the child, 3) Concern about the child’s experiences, and 4) Raising awareness and support for lifestyle changes.

Feeling that the child and the parents are being criticized

The public health nurse called the parents and informed them that their son or daughter had shown a considerable weight increase since the last measurement performed by the school health services. In our study, all the telephone calls were answered by mothers, and their reactions varied from surprise and anger to gratitude that someone cared. Some of the mothers were single parents, but when the parents lived together, the mother had discussed this communication with the father. Several said that they were unprepared when the public health nurse called, and that they felt ashamed and had a need to defend themselves. They stated that a letter in advance of the telephone call would have prepared them better.

Several felt that the child’s weight gain was not only a criticism of the child but also an indication that they had failed as parents:

‘But it’s like receiving a blow just where you’re most sensitive. And when it’s your child, it always hurts. And we kind of know that we haven’t done our job as parents. And there’s also an element of shame. You try to be positive and all that, but actually these feelings are still smouldering under the surface.’

Several of the parents in the study said that they too struggled with their weight, and that it was difficult to help the child with something they could not deal with themselves:

‘It was actually difficult thinking – now I have to go there (to the public health nurse), and I’m a bit heavy myself, and they might think that I’m not capable of eating sensibly.’

A wish to protect the child

All the parents felt that it was negative to direct too much attention to weight. They were worried that their child might acquire negative feelings about his/her own body, and at worst develop an eating disorder. Therefore, they did not want the child to be present during the sessions with the public health nurse, or that the nurse spoke to him/her alone about the weight development. There were variations in to what extent the parents told the child about their own participation in counselling sessions with the school health services, or why they were participating.

When both the child and the parents took part in the activities offered, several parents wanted to protect the child by saying that the activities were offered to all children. Other parents declined to take part because they were afraid that the child would be associated with ‘those who are overweight’.

‘And throughout the entire process he has never understood what he’s been part of. I don’t want him to go around thinking he’s fat, I don’t like the thought. I think he should have a good self-image, and that he should feel fine just as he is. The last thing I want is for him to find out in any way whatsoever that he’s chubby, or that he’s fat or that there’s something wrong with him, because there isn’t.’

Concern about the child’s experiences

Several parents said that the children perceived themselves as fat, and that they had said they were upset about this. Some of the children were very preoccupied with their weight, and weighed themselves every day. Several had received comments from their peers, and some had been teased by their fellow-pupils:

‘So he said himself that his tummy had grown big, and that he’d received comments in the shower at school that …, and he didn’t like that, so he was very upset about it. And this autumn he started Year 4, and they’ll have swimming so he’s dreading that, because of the girls.’

‘But he notices that when he has physical training, he soon starts sweating. And he thinks that’s uncomfortable. And he gets tired more quickly and lags a bit behind the others – they are faster.’

The mothers were frightened that the child would take it as a criticism if they limited their food intake. This was particularly challenging if the child was the only one in the family who needed such restrictions. Several mothers wanted more attention paid to healthy food in teaching at school – as a topic for all the children regardless of weight. It was difficult, for example, if other children took food to school that their child had been told was ‘off limits’.

Raising awareness and support for lifestyle changes

Despite feelings of shame and guilt, the mothers said that they wanted information about the child’s weight gain. Some had not been aware that the child had gained so much weight, and the counselling sessions with the school health services had raised their awareness sufficiently to deal with the situation. Others wanted closer follow-up and were very satisfied with both the activity groups and the counselling sessions.

Taking part in physical activity without pressure to excel was a new and positive experience for the child. The mothers got ideas for different activities they could do together as a family, and that led to happy and satisfied children and positive parents. They received crucial support in their attempts to change the family’s routines, and felt it was positive that people other than the parents provided information about physical activity and a healthy diet. The mothers were aware that the child’s diet was their responsibility, but found it a challenge.

‘It feels good to sit around a table and talk about it, but how will we manage to do this at home, and how can we ensure that the children are happy with what we’re doing, without putting pressure on them in any way?’

Discussion

The interviews reveal that the child’s overweight is a sensitive issue for the parents. Several parents were also unprepared for being told that their child was in the overweight category, as other studies have also demonstrated. Parents are more frequently unprepared in the case of boys, and the younger the child, the more unprepared they are (14–16). Our study shows that it was difficult to involve the parents of four-year-olds; none of them wanted to be followed up by the child health clinic. Perhaps this is related to the fact that many do not think about overweight in connection with a small child (14), and public health nurses are often met with resistance when they point out the increase in a child’s weight.

A new study, however, shows that overweight can be predicted from an early age, and when a small child’s iso-BMI increases, this should be noted (17). Parents feel that their parenting skills are being questioned when health personnel call attention to overweight. This perception is heightened when the parents themselves are overweight (10), as our study also found. Moreover, they feel that criticism is being aimed at a vulnerable and innocent child (18). Several of the parents in our study had unsuccessfully tried to lose weight, and they did not want their child to have the same experience. We see similar findings in another study (14).

Uninformed, judgmental and disrespectful approaches to problems of overweight may lead to reluctance to seek help from health professionals (14, 19). Our study confirms that overweight is stigmatized and reflects norms in contemporary society. This confirms that the public health nurse’s professional attention to the child’s weight development demands both sensitivity and professionalism in the encounter with parents. The public health nurse must speak to the parents about the child’s weight and development, and find out what kind of help and guidance they want. It is vital to take the parents’ feelings of shame and guilt seriously when planning preventive measures (20).

Parents have ambivalent feelings

In our study, as in others (16, 18, 21), parents are afraid that a child will form a negative perception of its own body if attention is drawn to weight. Being the parents of a child with a big body can be perceived as an ambivalent process. On the one hand, the parents will do everything they can to ensure that the child is in good health and does not suffer from overweight. On the other hand, they have an even stronger desire for their child to have a good self-image (18). A longitudinal study of Canadian children aged 10–11 shows the correlation between overweight and the risk of developing low self-esteem and poor mental health later in life (21, 22). Children as young as four–five are preoccupied with their own bodies and what they look like (23), and several of the children in the study themselves thought that they were too fat, and had received comments from their fellow pupils and been teased.

The public health nurse plays a dual role in that he/she ‘warns’ the parents that the child is too heavy, while also counselling the child and the parents on how to achieve a good self-image. This poses a dilemma. It is vital that health professionals are concerned about the child’s self-esteem and mental health as well as the overweight (16, 19). The session with the parents should focus on the opportunity to safeguard the child’s self-esteem while initiating the necessary measures to stop the overweight. We know that it is better if the child outgrows its overweight as opposed to waiting for the child to put on even more weight, when it is more difficult to treat (17, 24).

Participated in activities

Parents of overweight children have different reasons for declining to take part in interventions against overweight. For example, some people are frightened that the child will be viewed as overweight (16), as was found in our study. It is important to take this challenge seriously so as not to do more harm than good.

Some mothers, nevertheless, chose to participate in the activity groups and found that being together with others with the same challenges was a help. They described how being physically active together with their own children and other parents and their children was a new and positive experience. Children’s sports activities often consist of various kinds of competitions instead of fun and games. Overweight children often feel a sense of defeat when they are not picked for the team, or when they realise that they cannot keep up (21). It is vital that there are alternative arenas where everyone can enjoy being physically active without being pressurized by a performance culture.

In our study, it was the mothers who participated in conversations and the activities offered. They explained that the fathers had no opportunity to participate. A systematic study of the literature shows that the mother often plays a more active role than the father in terms of the family’s diet (25), but in our study it emerged that the mothers may need support in this respect. The fathers can provide such support but research indicates that fathers often do not regard themselves as a target group for the work of the child health clinic (26). This gives pause for thought in terms of efforts to promote health.

The mothers in our study found the activities offered helpful, and they felt that they themselves were an important driver for activity and happy children. These perceptions are backed up by knowledge of the positive correlation between physical activity and self-image (21). Other studies also show that interventions focusing on physical activity and diet can have a positive effect on both weight and physical health (27, 28).

Although our study was small, and the findings cannot be generalized, it nevertheless provides important knowledge about parents’ experience with initiatives at the child health clinic and school health services.

Conclusion

Our study provides fresh knowledge about how parents perceive the encounter with the child health clinic and school health services regarding efforts to prevent overweight and obesity. Parents feel that the child’s weight gain is not only equated with criticism of the child but also criticism that they have failed as parents. Having an overweight child can entail a sense of shame. In order to protect their children, parents do not want to include them in dialogue with the school health services. Public health nurses play an important role in disseminating new information that overweight children can become overweight adults, and that the earlier attempts are made to reverse this adverse development, the better.

Lifestyle interventions can have a positive effect on the child’s weight development and health, and the public health nurse must support the parents in efforts to safeguard the child’s self-esteem in parallel with making changes to the level of activity and the diet. The study reveals that mothers feel that counselling sessions with the school health services are helpful, as is participation in the activities offered where they meet others in the same situation.

A positive feature was that the intervention involved both parents and children, and that the competitive element was replaced by fun and games. However, it is vital to focus more on including the fathers. The parents who did not wish to participate in the activities offered found it problematic that the child might be associated with being overweight. More research is needed on how lifestyle interventions can prevent overweight and safeguard the child’s self-image.

References

1. Sosial- og helsedirektoratet. Kommunenes helsefremmende og forebyggende arbeid i helsestasjons- og skolehelsetjenesten: veileder til forskrift av 3. april 2003 nr. 450. Oslo: Sosial- og helsedirektoratet. 2004.

2. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonale faglige retningslinjer for veiing og måling i helsestasjons- og skolehelsetjenesten. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet. 2011.

3. Kipping RR, Jago R, Lawlor DA. Obesity in children. Part 1: Epidemiology, measurement, risk factors, and screening. BMJ 2008;337:a1824.

4. Kipping RR, Jago R, Lawlor DA. Obesity in children. Part 2: Prevention and management. BMJ 2008;337:a1848.

5. Elinder LS, Heinemans N, Zeebari Z, Patterson E. Longitudinal changes in health behaviours and body weight among Swedish school children – associations with age, gender and parental education – the SCIP school cohort. BMC Public Health 2014;14:640.

6. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonale faglige retningslinjer for primærhelsetjenesten: forebygging og behandling av overvekt og fedme hos barn og unge. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet. 2010.

7. Juliusson PB, Eide GE, Roelants M, Waaler PE, Hauspie R, Bjerknes R. Overweight and obesity in Norwegian children: prevalence and socio-demographic risk factors. Acta Paediatr 2010;99(6):900–5.

8. Øvrum A. Socioeconomic status and lifestyle choices: evidence from latent class analysis. Health Economics 2011;20:971–84.

9. Øvrum A, Gustavsen G, Rickertsen K. Age and socioeconomic inequalities in health: Examining the role of lifestyle choices. Advances in Life Course Research 2014;19:1–13.

10. Juliusson PB, Roelants M, Eide GE, Moster D, Juul A, Hauspie R et al. Growth references for Norwegian children. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2009;129(4):281–6.

11. Barth T, Børtveit T, Prescott P. Motiverende intervju : samtaler om endring. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2013.

12. Kvale S, Brinkmann S, Anderssen TM, Rygge J. Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. 2. utg. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2009.

13. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning: en innføring. 3. utg. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget 2011.

14. Toftemo I, Glavin K, Lagerlov P. Parents’ views and experiences when their preschool child is identified as overweight: a qualitative study in primary care. Fam Pract 2013;30(6):719–23.

15. Juliusson PB, Roelants M, Markestad T, Bjerknes R. Parental perception of overweight and underweight in children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr 2011;100(2):260–5.

16. Newson L, Povey R, Casson A, Grogan S. The experiences and understandings of obesity: families’ decisions to attend a childhood obesity intervention. Psychol Health 2013;28(11):1287–305.

17. Glavin K, Roelants M, Strand BH, Juliusson PB, Lie KK, Helseth S et al. Important periods of weight development in childhood: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:160.

18. Haugstvedt KT, Graff-Iversen S, Bechensteen B, Hallberg U. Parenting an overweight or obese child: a process of ambivalence. J Child Health Care 2011;15(1):71–80.

19. Turner KM, Salisbury C, Shield JP. Parents’ views and experiences of childhood obesity management in primary care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract 2012;29(4):476–81.

20. Øen G. Forebygge overvekt hos barn og unge – et økologisk perspektiv. In: Holme H, Olavesen ES, Valla L, Hansen MB (eds.). Helsestasjonstjenesten: barns psykiske helse og utvikling. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2016. p. 481–94.

21. Danielsen YS, Stormark KM, Nordhus IH, Maehle M, Sand L, Ekornas B et al. Factors associated with low self-esteem in children with overweight. Obes Facts 2012;5(5):722–33.

22. Wang F, Wild TC, Kipp W, Kuhle S, Veugelers PJ. The influence of childhood obesity on the development of self-esteem. Health Rep 2009;20(2):21–7.

23. Goodell LS, Pierce MB, Bravo CM, Ferris AM. Parental perceptions of overweight during early childhood. Qual Health Res 2008;18(11):1548–55.

24. Lekdahl S, Holme H. Overvekt og fedme hos barn. In: Holme H, Olavesen ES, Valla L, Hansen MB (eds.). Helsestasjonstjenesten: Barns psykiske helse og utvikling. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk. 2016. s. 241–56.

25. Savage J, Fisher J, Birch L. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. Journal of Law and Medical Ethics 2007;35(1):22–34.

26. Sheriff N. Engaging and supporting fathers to promote breastfeeding: a new role for health visitors? Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 2011;25:467–75.

27. Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur L, Burrows T, Stewart L, Neve M et al. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012;130(6):e1647–71.

28. Reinehr T. Lifestyle intervention in childhood obesity: changes and challenges. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2013;9(10):607–14.

Comments