International student exchange in Africa – the experiences of nursing students after returning home

On returning home from their clinical placement in southern Africa, the nursing students missed having someone to share their intense experiences with.

Background: Student mobility and international collaboration are essential prerequisites for the international community to be able to train responsible, committed nurses. In Norway, the national target is for 50 per cent of all students to take part in an international exchange programme during their time in education. With increased student mobility in higher education comes a need for more attention to be paid to the transition from studying abroad to returning home and the ensuing period.

Objective: The study’s objective was to increase the knowledge of nursing students’ experiences of returning home after a clinical placement in southern Africa.

Method: The study has a qualitative explorative design. Over a period of six months, we conducted multi-stage focus group interviews involving ten students for the first interview, eight students for the second and five students for the third interview. The data material includes reflective notes and an end report from the students’ period abroad. The analysis was based on Malterud’s systematic text condensation method.

Results: The nursing students described the time immediately after returning home by referring to a sense of emptiness – a feeling of being alone, emotionally and morally, with their experiences from their clinical placement abroad. It became apparent during this period that they were missing the fellowship they had shared with other students on the international exchange programme. Their self-assurance and confidence as healthcare professionals were strengthened. They also developed cultural sensitivity and an awareness of the importance of this in a multi-cultural context.

Conclusion: The study increases the knowledge of how nursing students experience returning home after an exchange. The students reported that they felt alone with recollections of intense experiences, and they missed sharing these with fellow students from the exchange programme. This demonstrated a need for nursing courses to facilitate better and more structured follow-up of students’ re-entry, to help them process and acknowledge their experiences. There is a need to conduct further research into students’ experiences of international clinical placements with a particular focus on the time after returning home.

Introduction

International exchange has become an important part of the bachelor programme. Student mobility and international collaboration are prerequisites for training responsible and committed participants for roles in the international community (1, 2).

In 2015, fifteen per cent of Norwegian students took part in international exchange programmes, and the long-term objective is for this to be increased to 50 per cent. While it is necessary and important to increase student mobility in higher education, improving the quality of the study programmes for those who travel overseas will remain key (1–4).

Knowledge about global health challenges and nursing practice in an international perspective are among the learning outcomes listed in the Regulations on National Guidelines for Nursing Education (5). Oslo Metropolitan University has signed inter-institutional Erasmus agreements with countries in southern Africa.

Every year, 30–50 nursing students in the 2nd year of their course spend three months working in health promotion and prevention placements, while third-year students spend three months in surgical/medical practice in a hospital setting. During their exchange period, students are required to keep reflective notes and to compile an end report from their placement. Entry to the exchange programme is by interview combined with good average grades.

Oslo Metropolitan University provides a mandatory preparatory course for exchange students assigned to placements in the global South. The course focuses on cultural awareness, safety and suitability. Throughout their period abroad, the students attend weekly monitoring sessions with a teacher at their home university who draws on international experience. A coordinator from the host country meets up with the students every two weeks.

International exchange and cultural sensitivity

Nursing students’ clinical practice in two public hospitals in southern Africa formed the context and starting point for this study. This particular African country has been struggling with health challenges for many years, and the population has been severely affected by HIV and AIDS. Other challenges include road traffic accidents, violence, knife injuries and burns, as well as alcohol abuse. Due to a shortage of doctors, registered nurses (RNs) are assigned to a wide range of tasks, while authoritarian and hierarchic attitudes towards patients prevail (6, 7).

A quarter of the population is categorised as poor. Nevertheless, this part of Africa is plagued by fewer political and economic conflicts than previously, and society is more stable than it used to be. Child mortality, the number of qualified nurses and midwives, as well as public-sector spending on health are generally the most important indicators of differences between southern Africa and Norway. These factors give good grounds for prioritising the health sector in the years ahead (6, 8).

Students are confronted with vast contrasts when faced with disparate healthcare systems. There are however many reasons for wanting to take part in overseas exchange programmes. Research tells us that the benefits of international student exchange include professional and personal growth, new cultural encounters, and improved confidence (4, 9–14).

Students who are exposed to different and unfamiliar learning environments find that their ability to collaborate and adapt improves. They have also been found to be valued as responsible and active employees in connection with international collaboration and when handling cultural challenges (2, 4).

Clinical placements abroad have an important part to play in increasing the level of nursing students’ understanding of other countries’ healthcare systems and developing their cultural competence (9, 12). According to Papadopoulos (15), cultural sensitivity is one of the precursors to developing cultural competence, which is in strong focus in this context. Cultural sensitivity is defined as the ability to understand other people’s values and world view by learning about and reflecting on other cultures. Such reflection requires awareness of one’s own attitudes and starting points (15, 16).

Students see the other party’s world through the spectacles of their own lives and interpret cultural expressions from their own point of view rather than the other person’s thoughts and feelings. Cultural sensitivity is an approach to communicative skills and attitudes that requires empathy, trust, respect, and acceptance. Demonstrating sensitivity in encounters with another person involves making use of both affective and cognitive abilities (15, 16).

Returning home after an overseas exchange

The initial period after returning home from a practice and study placement in Africa represents an intercultural transition phase. Gaw (17) refers to the experience of this phase as ‘the reverse culture shock’. A culture shock is the sense of disorientation we feel when adjusting to a different culture. The reverse culture shock involves a further transition that can entail unexpected challenges.

Expectations surrounding re-entry incorporate a cognitive dissonance – what students expect of their inner circle and their loved ones is inconsistent with changes within their own selves. Studies show that students find insufficient interest voiced by friends and family and at their place of education (18–20).

Altered values and a recognition that one’s point of view is different after the exchange have generated feelings of stress, yearning and loneliness. Other factors that are pointed out in connection with the transition phase after returning home include other people’s inability to comprehend the experiences and learning that students have acquired abroad (17–19).

In other words, intercultural transition phases after the exchange can give rise to challenges. Recent experiences, different ways of practising nursing, and knowledge recently acquired in an unfamiliar learning arena that is rich in contrasts are all factors that require extensive processing.

The literature in the field appears to be fragmented and tends to under-communicate the nursing students’ professional and personal situation. It is therefore necessary that we turn our attention to the students’ re-entry after the exchange and the immediate period thereafter.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain more knowledge about the experiences of nursing students after they returned home from a period in southern Africa.

We asked the following research question: ‘What themes preoccupy nursing students after they return home from a clinical placement in Africa?’

Method

Sample and data collection

The study has a qualitative explorative design. We conducted multi-stage focus group interviews over a period of six months with ten students taking part in the first interview, eight in the second and five in the third interview. When working with multi-stage focus groups it is sufficient to involve a single group with approximately the same number of participants in each interview (21).

All of the ten students who took part in the exchange programme in the autumn of 2019 were invited to a group interview after returning home. The participants were third-year students on the bachelor’s degree course: one man and nine women between the ages of 20 and 25.

The group interviews were conducted in the spring of 2020. In January they took place on campus, but due to COVID-19, the interviews were conducted using the Zoom platform in March and June. The first and second interview sequences lasted for 90 minutes and were minuted. The third sequence was an hour long and was recorded for later transcription.

The participants felt secure in one another’s company and that of the second author, who had been their supervisor during their overseas placement. By engaging in an affirmative dialogue during the first group interview, the participants and authors developed a shared interest in exploring the themes. This was achieved by conducting two follow-up group interviews three months apart.

This multi-stage focus group interview can be seen as an exploratory dialogue designed to provide opportunities to enrich the data material further in each sequence, and to arrive at a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences (21). At the same time, the method provided scope for us to confirm our interpretations of the data obtained at earlier stages, which in turn helped to strengthen its credibility.

The approach is suitable for use in explorative and descriptive studies (21, 22). The reassuring setting allowed the participants to share themes of a sensitive nature. Some themes were characterised by vulnerability and strong emotions in connection with the use of coercion in the treatment of children and dying patients being kept in an unhygienic environment. It was important for the moderators to be attentive to sensitive situations the participants had experienced, and to provide appropriate affirmation (23).

Data material

The data material is based on three group interviews, ten reflective notes and one group report written at the end of the exchange. The interview minutes and transcriptions, the end report and the reflective notes were dealt with as a single body of text.

The group interviews produced rich descriptions of themes that concerned the participants at different points in time. The end report and reflective notes described the exchange, but related to impressions formed during a specific, pre-defined period of time. They complemented the material provided by the interviews.

The notes and the report generally focused on cultural similarities and differences between healthcare systems. The first group interview asked three open-ended questions about experiences during the placement period, experiences after returning home, and any other themes the students might want to discuss. After the first group interview, we devised a semi-structured interview guide based on key themes in the first interview sequence.

The theme for the third interview was informed by topics raised by the students in the second interview sequence, and this gave further nuance and richness to their experiences. Consequently, the students’ reflections developed within the time frame of the interviews (21).

The concept of ‘emptiness’ provides an appropriate example. This was mentioned by several participants during the first group interview and was repeated in sequences two and three, thus allowing us to arrive at a richer description of the meanings assigned to this concept by the students.

Their experiences related to returning home from the overseas exchange and highlighted feelings of being alone with recollections of intense experiences and missing the group of students who had been abroad together. Their everyday life at home gradually gained prominence as the intensity of these experiences faded away. The period of six months after re-entry provided time for them to process their experiences and to acknowledge them in a new light.

Data analysis

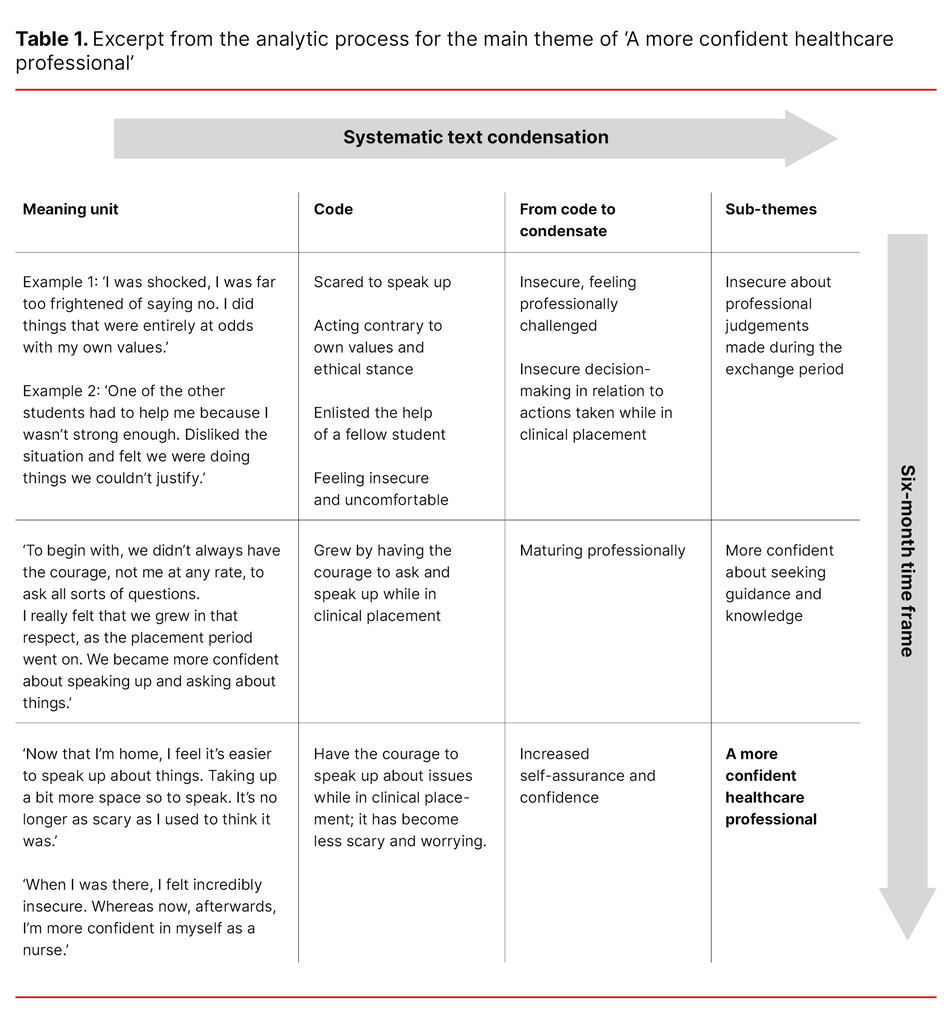

The data analysis was based on Malterud’s four phases of systematic text condensation (STC): 1) overall impression – from chaos to preliminary themes, 2) meaning units – from themes to codes and sorting, 3) condensation – from code to abstracted meaning, and 4) synthesis – from condensation to descriptions, concepts and results (22).

The full text was read by both authors to allow them to form an overall impression and to identify preliminary themes associated with the research question. After a systematic review, we identified meaning units to allow us to agree on how to interpret the material. The units were coded, after which we arrived at condensates. We proceeded to discuss the condensed meanings and arrived at sub-themes that summarised what was on the students’ mind after returning home.

The period of time over which the three group interviews were scheduled was a factor that allowed reflections to develop. Through our analysis, we arrived at three main themes, as listed in the Results section. Table 1 includes an example of a main theme (italicised). In the Results section, all the main themes are described in full and supported by quotes.

Research ethics

In order to ensure that both authors would have the same overall impression of the data material, it was necessary for the first author to obtain permission to view the participants’ reflective notes. An application was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) under reference number 188588.

The students received information about the project and signed a declaration of consent. Anonymity was ensured by coding printouts, and the results were presented to the participants prior to publication. We used COREQ for all our reporting.

Results

The results of the study show that three main themes preoccupied participants after re-entry: 1) A sense of emptiness after returning home, 2) A more confident healthcare professional, and 3) Developing cultural sensitivity. Quotes are coded; participants are referred to as S1–S8 and the end report as ER.

A sense of emptiness after returning home

This theme was subdivided into two sub-themes: a) ‘Being alone with recollections from the clinical placement’, and b) ‘Missing the fellowship of other students from the exchange’.

Being alone with recollections from the clinical placement

In all the data collection sequences, participants expressed a sense of emptiness after returning home. In the initial period after the exchange, they described this as a feeling of being alone with their recollections. Although the people around them showed an interest in hearing about their time abroad, the students held back and did not communicate important, intense aspects of their placement period. For some of the participants, being alone with these experiences was an overwhelming feeling:

‘To start with, we all returned home, each to our own. There was no-one to talk to about having been to Africa, because people don’t tend to understand what we have been a part of. There are such a lot of things we need to talk about, that can’t be addressed in the same way when we talk to people we didn’t share those experiences with’ (S5).

In S5’s words: ‘I’m unable to recount it all, and I can’t share the important things. I can hardly bear thinking about it, there is such a lot of it. I feel I need to establish some distance to it.’

In the second sequence, three months later, the existential void in social settings is described as persisting, but the time that had passed put the events of the exchange period at a greater distance. Developments since the previous group interview showed that the students continued to have these thoughts and still felt a need to talk about and share their experiences.

S3 described it in these terms: ‘You [the fellow students] know what we have been through, but it was worst during the first two months [after returning home]. Then it gradually faded, that constant churning of thoughts. But I do keep thinking about it.’

The most intense impressions appear to fade over time, but recollections and thoughts relating to the exchange remained with them.

Missing the fellowship of other students from the exchange

It emerged that during the period of the exchange, the fellowship of other students on the programme was important. This provided them with a perspective and a forum for sharing and putting words to their own experiences during the placement period.

It became apparent after re-entry that they were missing this fellowship: ‘Even if you were in the company of others, you were still alone in a way. You were spending time with people who hadn’t been a part of some of the things you had been doing. So, all you had was your own thoughts’ (S3).

After six months at home, the participants still felt a sense of loss from being separated from their group as they all went on to follow their own educational paths: ‘I feel a need to talk about it [the exchange]. This group of people understand me best, and if I suddenly think of a situation then it’s not a particularly natural thing to – not everyone is that keen to hear about my experiences and what I’ve been thinking’ (S2).

The students felt a need to remember and to share their experiences with the group. Their period abroad was a shared reference and they found that this brought understanding and fellowship.

A more confident healthcare professional

Being confronted with challenging situations in the field of practice made a strong impact on the students. They had dealt with situations that gave rise to ethical dilemmas, but that nonetheless raised the participants’ awareness of their own professional values. They felt it was unethical and frightening to be restraining and tying up unruly or aggressive patients while caring for them:

‘After experiencing this situation, I have been giving it much thought and reflection. These were things that were completely at odds with my own values as a human being, and as a soon-to-be nurse. The four most important ethical principles of nursing, which are beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy and justice, were all totally ignored by the nurse in this situation’ (S8).

Difficult situations gave rise to uncertainty in several participants. Having to restrain frightened, crying children who were suffering from burns was distressing and unpleasant. Degrading, unhygienic situations involving dead fetuses gave rise to thoughts of disrespect for their intrinsic human worth.

The situations they found themselves in triggered a need for reflection among the participants and they shared knowledge among themselves both during and after the placement period. The different group interview sequences demonstrated development over time; there was a growing awareness of their own values and learning:

‘Before, I was never entirely aware of my own values and my nursing values, but in practice it’s all very black-and-white what I can justify and what I cannot. We frequently found ourselves in situations that quite simply were awful for us to be in, and that’s something I will bring with me. It’s a good experience to know where you stand as a nurse’ (S6).

After re-entry and clinical practice in Norwegian hospitals, the participants’ confidence grew from feeling insecure while in practice overseas to becoming more self-assured as healthcare professionals and being less worried about raising challenging situations with their practice supervisor at home. See Table 1.

Developing cultural sensitivity

This theme deals with the students’ reflections surrounding various cultural expressions encountered while in a different clinical setting. During their placement, their emotional and empathetic abilities were challenged. The participants often found that the relationship between the doctor, the nurse and the patient was marked by an authoritarian attitude and a lack of communication.

S8 explained: ‘There was no communication with the patient. I think he was terrified because he never received any information about what was going to happen. […] suddenly having a tube stuck down your throat must be really uncomfortable when you’re not prepared for it.’

Their stories were rich in contrasts and ranged from shock, worry and uncertainty to being emotionally impacted. The absence of information, reassurance and encouragement, and situations where women in childbirth were roughly treated and chided by nurses or midwives, were upsetting experiences. However, the participants also received the gratitude of patients they had calmed down, supported and comforted.

The participants reported to be humbled by and aware of the importance of cultural sensitivity, and how, in some cultures, care must be provided and actions taken with the resources available and based on a different world view. The participants’ adaptability and sensitivity gradually grew stronger, which made it easier for them to understand and deal with the unfamiliar on the host country’s terms, without using their own personal world view as a yardstick:

‘Lately we have reflected on several things, and we now see them in a different way. They are extremely skilful, and despite having access to very little equipment they are able to find solutions and make ends meet. Considering their knowledge, funding and equipment, they did their very best based on their understanding’ (ER).

The rough and sometimes shocking treatment of patients gradually became easier for the participants to understand as their insight grew and they learnt more about the healthcare system’s premise and circumstances: ‘Thanks to our exchange placement, we find that we have acquired valuable insights into a different culture. We believe that this will give us greater tolerance, acceptance and understanding as future nurses’ (S6).

The students’ reflections demonstrated how their experiences may be transferable to their work as fully qualified RNs.

After returning home, the students developed greater awareness of their own culture as seen from a different perspective, and they came to cherish this after their experience of being foreign in a culture that was different to Norwegian culture: ‘I now have greater understanding for what it’s like to be a minority when I encounter patients from other cultures in clinical practice’ (S3).

S2 followed up: ‘I am very grateful, not only for having learnt about other cultures and ways of practising nursing, but for being able to appreciate what we have, and reflecting on our own lives and the advantages we have because we grow up in an affluent society.’

Discussion

The study’s objective was to increase our knowledge about the experiences of nursing students after returning home from clinical placements in southern Africa.

The time after re-entry, and follow-up of exchange students

One of our main findings deals with the emptiness that students felt after returning home from abroad. The participants linked this to a notion that their own networks had no frame of reference that would allow them to understand their recent experiences and learning situations in a foreign culture. It appears that this emptiness reflected an imbalance between their expectations of returning home and their preparedness for the transition phase after re-entry.

Students who have completed an exchange acquire a perspective that cannot be grasped by members of their home community because they have no frame of reference that will allow them to do so. Other studies describe students who distance themselves from their loved ones by holding back on communicating details or impressions from their exchange, so as not to offend anyone (24).

However, our study shows that the students were left feeling that there was no-one they could share important experiences with. This could also refer to unspoken expectations of the closest group of friends and fellow students. No-one asked the participants about their intense and upsetting experiences. This may serve to undermine the students’ need to verbalise their recollections.

The group of fellow students in whose company they spent large parts of their overseas placement were no longer available in the way they used to be. There was no-one for the students to exchange experiences with, which reinforced their sense of emptiness. Their expectations of returning home to their normal surroundings were transmuted into an unexpected further transition phase (17, 20, 25).

The fact that the students were missing the fellowship of other students highlighted the importance of togetherness and having access to a meeting hub where students could exchange and express thoughts and events with others who shared their frame of reference. Based on the study’s findings, it would be natural to ask nursing education programmes to address the need for support networks linked to intercultural transition phases.

Flobakk-Sitter (26) argues that study programmes should include the educational dimension of internationalisation to a greater extent. Educational institutions can be supportive and nurturing bodies that allow students to process and enrich their positive experiences, as well as their more profound experiences, during and after clinical placements in an international setting.

The intention behind a post-exchange follow-up programme is to help reduce the students’ sense of being alone in dealing with the emptiness. However, the education authorities’ aspirations to increase student mobility may introduce changes to the various institutions’ internationalisation programmes (2, 4).

Jansen et al. (20) outline a structured professional programme that provides follow-up before and during the exchange, as well as during the adjustment process that follows after returning home. The findings of our study suggest there is a need for such measures to be introduced in the time immediately following re-entry. By way of an example, such measures could involve group get-togethers at regular intervals, with a supervisor, or two or more students from the group placed in the same location.

An educational programme that promotes reflection and provides recognition of the students’ experiences can help them become more aware of their own competencies and give them an opportunity to benefit further from their overseas exchange. The nursing courses, for their part, may find that providing follow-up for students in the period after re-entry provides access to further knowledge about international exchanges. It may also help to uncover themes that ought to be further examined.

Professional and personal learning

Another important finding was the nursing students’ development of confidence in their own role. Recognising cultural and professional differences, on top of putting themselves outside of their comfort zone, gives significant professional and personal learning (9, 11, 12).

The students were involved in complex and challenging situations in an alien and different learning context which involved ethical uncertainty and a feeling of helplessness. However, engaging in conversations with fellow students, and with supervisors in the host country and at home during the placement period and after returning home, gives greater awareness of one’s own competence. Studies show that support and guidance during an overseas placement is essential for students (14, 27).

Such support provides an opportunity to verbalise experiences and can ease the process of adjusting to practice placements at home (18–20).

The students also linked their growing confidence with nursing values. Ethical guidelines for the nursing profession establish that the role of RNs is to promote the patients’ dignity and integrity and to protect patients from disrespectful treatment (28).

An awareness emerged among the participants about their own ethical stance. This helped to boost their confidence and made it easier to navigate in new and unfamiliar learning situations. Their experiences had made them more self-assured in encounters with challenging situations in practice placements at home, and had made them more receptive to cultural differences. Overseas exchange programmes create greater engagement in own learning, increased understanding of ethical problems and an ability to communicate in an international context (4).

There is nevertheless a need to highlight the role played by educational institutions in the host country as well as in the home country when it comes to following up on learning situations where international practice provides professional and ethical challenges (29, 30).

Increased awareness of cultural sensitivity

When the students first encounter the new culture, their initial interpretations will be tainted by their Norwegian ‘spectacles’. What to them appears to be brutal and less than caring treatment of patients, and situations involving disrespectful communication and a lack of patient empathy, give rise to puzzlement and despair.

Contrasts are often the most conspicuous, and it is easy to moralise and pass judgement. Having the complexity of vulnerable situations explained to them, and being able to understand what motivates certain actions, will change attitudes and contribute to increased acceptance and respect of a different world view (12, 14).

Cultural sensitivity requires such understanding of the other party’s actions and world view, which in turn is an important premise for developing cultural competence. The findings show that over time, greater awareness and understanding emerged of the importance of sensitivity when facing unfamiliar situations. However, reflection was also needed.

The three group interviews gave the participants an opportunity to reflect. The interviews’ six-month time frame may in itself have been a significant factor that allowed for processing of the experiences.

The participants’ experiences made them more independent and self-assured in their encounters with cultural diversity in clinical practice after returning home. They had personal experience of representing a minority in a foreign culture and this had given them a perspective that allowed them to empathise with the other person’s position. They drew on their own experiences and treated the other party with trust and respect, which are important enabling factors for delivering culturally sensitive care (15).

Inquisitive, affirming and empathetic conduct and communication give scope to develop cultural sensitivity (15, 16). Making use of their sensitivity in this way involves using their cognitive as well as their affective abilities in an attempt to read and understand situations (16).

Methodology

One of the study’s strengths was the sincerity and candour of the participants’ descriptions, which gave depth to the themes and allowed for better comprehension. However, the findings cannot be generalised because the sample is too small. Only five participants attended the last sequence of the multi-stage group interview. An explanation for the smaller number of participants may be found in the weariness of Zoom meetings following the COVID pandemic.

Norway is working in partnership with other countries’ higher education institutions within and outside of Europe. A weakness of the study is that the sample only included placements in one of several partnering countries in southern Africa.

We have sought to describe our methodology and our analysis as transparently as possible in order to boost the credibility of the study. The original intention was for the group interviews to be conducted face-to-face in minuted meetings. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was more convenient to make an audio recording of the last group interview, which was later transcribed.

In our assessment, this procedure has not impacted on the analysis of the overall text or results.

Conclusion

The study’s findings provide greater understanding of the experiences of nursing students re-entry from an exchange, when they feel alone with their intense experiences and miss the fellowship of other students. Reflections during and after the placement abroad demonstrate strengthened professional confidence, development of cultural sensitivity, and recognition of the importance of cultural sensitivity in multi-cultural settings.

The findings imply a need to discuss the requirement for changes to and/or a strengthening of the nursing courses’ follow-up of exchange students. We recommend that further research is conducted into the short and long-term gains and experiences of nursing students after an international exchange.

The authors would like to thank the students who took time to take part in the study, and who shared their rich and valuable experiences with us.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Comments