Individual care plan at the palliative stage – helping relatives to cope

Establishing an individual care plan at an early stage of palliative care gives relatives hope and support. They also feel seen and their burden of responsibility is lessened.

Background: Patients at the end of life often want to stay at home, and how their relatives cope with the home situation can be crucial. In a patient pathway, an individual care plan can ensure interdisciplinary interaction with the patient and his or her relatives.

Objective: The objective of the study was to examine how an individual care plan at the palliative stage helped relatives to cope.

Method: A qualitative study was carried out. We collected data from two multi-stage focus groups consisting of 12 adult surviving relatives, and used a phenomenological hermeneutical approach to examine their experiences. The Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) approved the study.

Results: The informants described a challenging everyday life in a state of constant alertness. They perceived the individual care plan as a support. The content and process elicited resources and structure as well as creating meaning and coherence. The plan inspired the informants to feel hope, to feel that they were a resource and were part of a team surrounding the patient. ‘Person-centred’ care summarises the holistic understanding. The topics ‘Relieve the burden – share responsibility’ and ‘Knowing that someone cares’ are presented in the results section, and the focus areas ‘Relatives need support in order to be a care resource’ and ‘Person-centred collaboration’ are discussed in the article.

Conclusion: Having an individual plan for palliative care can help relatives to cope. Early establishment of an individual care plan, person-centred relationships and collaboration can strengthen user involvement and collaboration with relatives. The relatives’ burden can be lessened by clarifying important questions about treatment and the future. Strengthening relatives’ ability to cope paves the way for a better end of life at the palliative stage. Further research is needed on the factors affecting work on the individual care plan at the palliative stage and on collaboration with relatives.

Many patients at the end of life often want to stay at home, and how their relatives cope with the home situation can be crucial in fulfilling this wish (1–3). Policy and research documents emphasise that an individual care plan can ensure user involvement and interdisciplinary collaboration, and can highlight contact persons and the needs of patients and relatives (1, 4–6).

It is vital for a patient pathway that services are coordinated and holistic, that they secure good quality treatment and include relatives (6–9). This article is based on a study examining whether an individual care plan at the palliative stage helped relatives to cope (10).

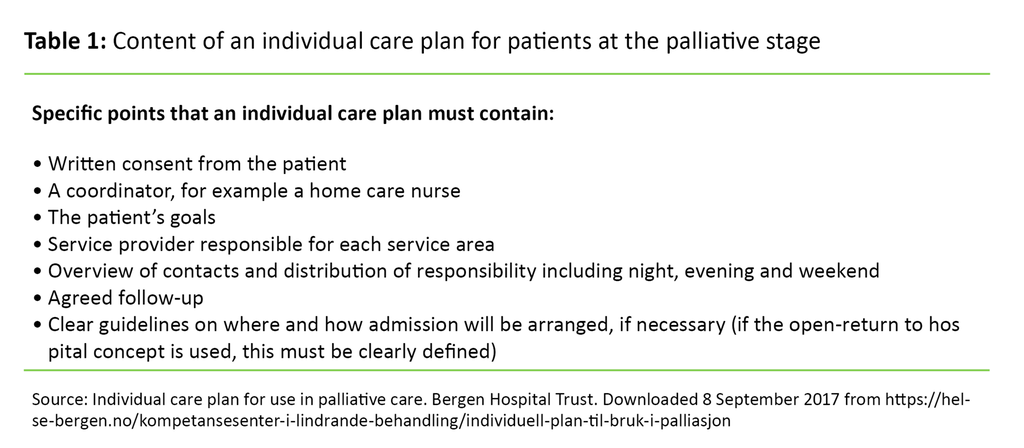

An individual care plan is an overall plan and tool that sets out what care services are required, goals, resources, service providers responsible, the coordinator and close relatives (4, 5, 11) (Table 1). When the patient requires the coordination of two or more services over time, this triggers a legal right to an individual care plan (4, 5, 11, 12). Legislation such as sections 2−5 of the Patients’ Rights Act and appurtenant regulations and guidelines (11, 12) sanction this right.

The patient must consent to the establishment of an individual care plan, the group responsible and the involvement of relatives. He/she shall define who is next of kin, cf. Section 1 paragraph 3b of the Patients’ Rights Act (4, 8, 12, 13). An individual care plan is considered to be a relational contract in which the service content of care services is clarified in a collaboration between the patient, relatives and service providers (14).

Palliative care consists of active treatment and holistic care for patients with an incurable disease and limited remaining lifetime. The aim is to achieve the best possible quality of life for patients and their relatives. Patients often present a complex clinical picture with frequent changes in their health situation that require coordinated follow-up by the health care services, and this triggers the right to an individual care plan. At the same time, individual care plans are infrequently used at the palliative stage (1, 15).

Search words and earlier studies

A literature search was undertaken in health care databases such as Oria, EBSCO-Cinahl, Ovid, Evidenced-Based Nursing, Cochrane, ProQuest, Norart, Idunn, Swemed. We carried out our search using the following MesH search terms: individual plan, individual care plan, patient care plan, caregivers, family, coping, palliative care, palliative care nursing and terminal care. Our last search was carried out on 16 May 2017.

There are a number of studies on the individual care plan (16–19), but none of them deal with both palliative care and the perspective of relatives. Several Norwegian studies deal with relatives as part of palliative care (20–26). In summary, the studies show that relatives want information, advanced care planning, support, and interdisciplinary and accessible health care services in order to cope with the complexities of everyday care provision.

Background for this study

‘Advanced care planning’ (ACP) consists of structured conversations aimed at clarifying wishes and needs (2, 6, 21). We have used the findings of the literature search to discuss the results of this study.

In our study, the experiences of relatives are examined in light of Antonovsky’s theory of salutogenesis (27). Antonovsky’s coping-oriented approach stresses factors that promote health and contribute to an overall sense of coherence (SOC). This requires that the inner and outer environment of the individual is comprehensible, manageable and meaningful.

This means having available resources and challenges that are worthy of involvement (27). Heggen depicts coping as the ability to tackle challenging, stressful situations and using one’s own resources to move on (28, p. 65). The question this raises is ‘How can an individual care plan at the palliative stage help relatives to cope?’

Method

We have conducted a qualitative study with a phenomenological hermeneutical approach (29). The phenomenological perspective consists of the subjective descriptions of the informants – the case itself. The hermeneutic perspective – the abstract meaning – emerges through analysis and interpretation of the transcribed conversations. We chose this approach in order to elicit the experiences of relatives with an individual care plan at the palliative stage.

The research design used was two multi-stage focus groups (30). Wibeck (31) refers to Morgan (1996) who describes the focus group as a research technique whereby data are gathered through group interactions between the group members in order to elicit qualitative data about a research issue chosen by the researcher. Teamwork and dynamic interaction among the informants will facilitate new insights and knowledge (32).

Multi-stage focus groups

In multi-stage focus groups, informants discuss topics and experiences in the course of several meetings. The dialogues create enhanced understanding by considering phenomena in detail and in depth, elevating the informants’ experiences to a higher level of abstraction (30).

The role of the moderator is to guide the informants’ conversation, maintain a balance between empathy and distance, listen and identify the meaning of what is expressed, ask key questions and ensure structure in the group conversations (31, 32).

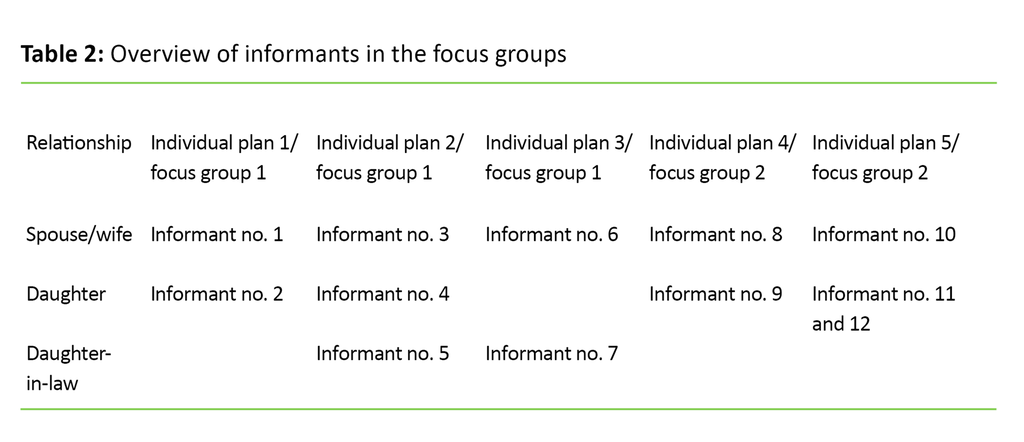

The multi-stage focus groups, which had five and seven female participants respectively, met three times, with six group meetings altogether. Table 2 provides an overview of the informants.

The informants were adult surviving relatives who had helped to design an individual care plan at the palliative stage. Their participation in the study took place between four and eighteen months after the death of an adult family member. The relatives were spouses, daughters and daughters-in-law recruited by health care personnel who were in contact with them during the palliative stage.

The sample represented five individual care plans that had been established late in the palliative stage – from four months to one week before the death. The informants were unknown to the researcher before they consented to participate. The researcher was the moderator of the groups. An interview guide with open-ended topics based on the research questions was used in order to promote dialogue and the exchange of experiences.

Topics that emerged from analysis of the data from the previous group meeting were introduced at the next meeting. This led to further elaboration of the topic. The Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), formerly the Norwegian Social Science Data Services, approved the study, which was carried out in accordance with research ethics’ legislation and guidelines for medical and health care research (10).

Phenomenological hermeneutical analysis

We chose Lindseth and Norberg’s (2004) method of phenomenological hermeneutical analysis (29). The phenomenological perspective, the lived experience, was described by the informants in the interviews. The hermeneutical perspective – meaning in a wider sense – emerged through the interpretation of the interview texts. The interpretation of the texts builds on Ricoeur’s hermeneutic circle, which moves between understanding and explanation (29).

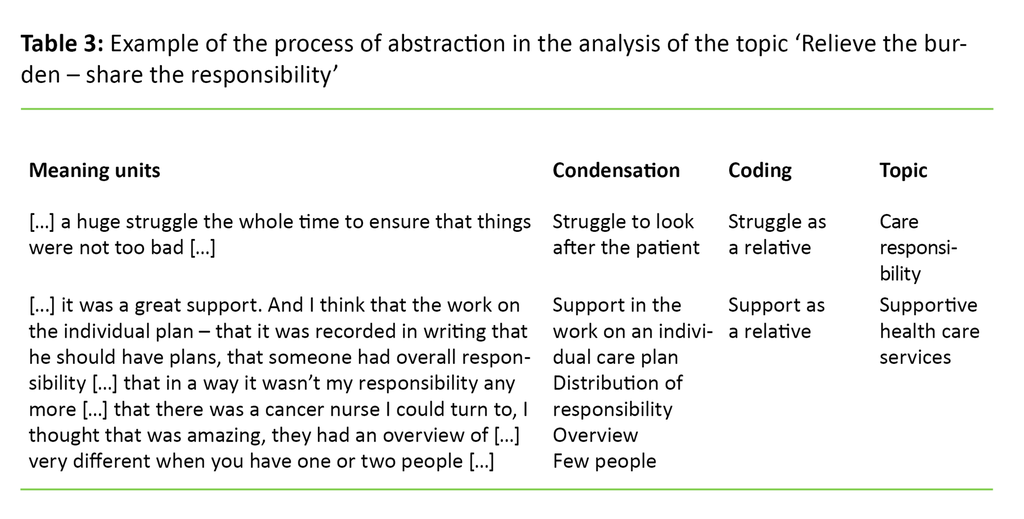

The steps in the analysis are 1) naive understanding, 2) structural analysis and 3) deeper understanding. Naive understanding is an initial read-through of the text in order to elicit a deeper understanding whereby the text ‘speaks to us’. Then we carried out a structural thematic analysis with interpretation of the transcribed text.

We divided the text into meaning units that were condensed and abstracted in order to elicit topics in light of naive understanding. Finally, we read and reflected on the text in order to elicit an overall understanding and to quality assure the correlation between naive understanding and the structural thematic analysis (29). Table 3 presents an example of structural thematic analysis in the study.

Results

The informants described a demanding and complex everyday life with serious illness and constant alertness with little sleep or relief. Several informants found it supportive to have a formal, individualised plan in which the coordinator, contact persons and therapists were named.

The article is based on a study with several findings: trusting relationships, holistic care and treatment, bringing hope and dignity, the struggle of relatives, support for relatives and the final hours together (10).

The further analysis and literature search highlight the perspective of relatives, and findings are reformulated. ‘Person-centred care’ summarises overall understanding, and in the article we present topics such as ‘Relieve the burden – share responsibility’, and ‘Knowing that someone cares’.

Relieve the burden – share responsibility

Receiving an individual care plan was like ‘bringing order to chaos’ according to one informant and gave a sense of security in an uncertain situation.

Informant 6 said: ‘[…] you get a real sense of security as when everything else is up in the air […].’

Being met in a good way was important for establishing trust in the health care services. The content of the individual care plan clarified what professional resources could be contacted at different levels of the health care services. The informants found that there was better planning and more holistic care when a care group supported the family. Participating in the planning prepared the informants even though the patient pathway differed from what had been planned.

At the end of life when there was a great need for symptomatic relief, a coherent, interdisciplinary 24-hour service gave the informants a sense of security because they perceived that the health care services collaborated and were better informed, in contrast to the time prior to the establishment of an individual care plan.

One of them said: ‘[…] we knew them, we felt safe […] it was positive even though it was sad […].’

The informants stressed that the GP is of central importance and must be involved at an early stage. In a more peaceful pathway, where there are good relations with the health care services, an individual care plan was not so important.

Several informants perceived being part of the decision to terminate life-prolonging treatment as a burden that affected their grief afterwards. When such a decision had to be made, the patient was too ill to make this choice. An interdisciplinary meeting in connection with the individual care plan at which the treating physician made the final decision was nevertheless a good support. The informants were of the opinion that the question of life-prolonging treatment should have been clarified with the patient and should then have been embedded in the individual care plan.

The informants emphasised that information must be given and an individual care plan established early in the course of the disease. At that time, the patient is strong enough to understand what an individual care plan is, and can be involved in the planning.

Knowing that someone cares

The process surrounding the individual care plan was more important than the document. The coordinator was described as a mentor for the patient – a professional who prioritised time, inspired confidence and established a dialogue that gave strength and support. The informants reported meeting professionals who were familiar with the patient’s situation and they knew that someone in the health care services ‘cared’. ‘That someone cares, and that there are plans for a life – a plan for a dignified life,’ explained informant 12.

Patients and relatives took part in the planning. Individual care plans often included the goal of being at home. Activities were planned so that life was not merely ‘waiting for death’. This goal gave patients and relatives a hope – not of recovery, but something to strive for in order to regain a zest for life.

Informant 9 said: ‘[…] what I hoped – we can’t demand that he recovers. But that he can walk around or be at home as much as possible.’

The support the informants experienced in the planning process was particularly important.

‘I found it was a huge support. And I think the work on the individual care plan – that it was recorded in writing that he should have plans, that someone had overall responsibility, that there was an overview […]. So when we received this plan – I felt that a terrible responsibility was kind of shared.’ Informant 2

Discussion

Our findings show that an individual care plan was vital in creating meaning and coherence. In order to shed light on how the individual care plan can help relatives to cope, we will discuss ‘Relatives need support to be a care resource’ and ‘Person-centred collaboration’.

Relatives need support to be a care resource

Studies show that relatives need care and support in order to be resource persons for the patient (1, 7, 8, 13, 20, 22, and 33). Milberg writes that relatives experience uncertainty and anxiety when no family-based and professional health care support is available at the palliative stage (3).

Sørhus, Landmark and Grov’s study (22) confirms that relatives need information and support from the health care services, while at the same time they feel responsibility, a sense of coping and meaning in the care tasks they perform. In Fjose et al.’s study (20), relatives confirm how valuable the meaningful and yet challenging end of life stage is.

For the informants in our study, it was challenging to have a family member who was seriously ill and at the same time find themselves in a situation characterised by uncertainty and helplessness. They felt that having an individual care plan and being part of a team surrounding the patient lessened their responsibility. Moreover, they found that having a coordinator and an individual care plan created order, and gave them an overview of relevant professional resources and a plan for the time ahead.

This reduced their uncertainty and made everyday life more comprehensible and manageable. According to Antonovsky, receiving support in challenging situations can help people to understand, perceive meaning and cope with the situation (27).

Relatives in a dilemma

Milberg points out that relatives can experience conflict between the patient’s wish to die at home and their own uncertainty as to whether they will be able to cope with this (3). Stensheim, Hjermstad and Loge reveal that relatives experience great responsibility and strain, and must be seen and looked after (34). Collaboration between the relatives, the collaborating care services and the coordinator then becomes crucial. According to Breimo, Normann, Sandvin and Thommesen’s study, work on an individual care plan gave a feeling of security and of being taken seriously, and the coordinator was perceived as being more important than the plan itself (4).

In contrast, substance users in Humerfelt’s study (16) found that an individual care plan did not lead to coordinated, holistic and individually-adapted services. They experienced a lack of participation, disappointing follow-up and disrespectful behaviour. This shows the importance of the coordinator’s attitude and dedication towards securing user involvement in the planning process. Holum and Nilssen’s studies show that a good process in relation to the individual care plan strengthens user involvement and empowerment (14, 18).

The informants in our study felt that the coordinator alleviated relatives’ burden by acting as a support and a mediator between patients and relatives. In retrospect, they saw this time as a strength during the grieving process. The study shows that the process of putting in place an individual care plan – with a better information flow, distribution of responsibility and overview – created meaning and coherence.

Person-centred collaboration

When working on the individual care plan, informants met professionals who had knowledge of the patient’s situation, and they knew that someone in the health care services cared. This created hope and meaning. The planning work ensured greater commitment, and provided goals to strive for and a perception of being seen as a person, as Alves’ study confirms (17).

Alidina and Tettero (35) refer to Dufault and Martocchio’s definition of hope (1985), whereby hope can highlight strategies and motivation for reaching goals. The study showed that patients at the palliative stage needed hope in order to maintain their dignity, cope with stress and achieve a better quality of life. Hope is therefore an important resource in coping with life-threatening illness. The work on the individual care plan backs up this hope while our study also shows that relatives felt that they did not have to cope with the responsibility alone.

Must look after the relatives

The relatives Grøthe interviewed said it was important to encounter professionals with dedication and expertise who kept them informed and attended to their needs (23). Relatives in Michael’s study wanted a plan for the future, even though the discussions were confrontational. This could secure patient involvement, information, joint decisions and support for relatives (36).

The informants in our study said that the question of life-prolonging treatment and of where the patient wanted to be cared for at the end of life stage should have been clarified with him/her earlier, and this should have been included in the individual care plan. Such clarification would alleviate the situation of relatives. Bollig, Gjengedal and Rosland’s study (21) supports this since relatives in their study found that having to take important choices at the end of life stage was a burden because they were uncertain of the patient’s wishes.

At the same time, patients in the study who lived in nursing homes had faith in leaving these decisions to relatives and health care personnel. The study concludes by stressing the need to systemise advanced care planning in order to clarify future wishes and thereby reduce relatives’ burden. Likewise, Gawande (37) points out that patients and relatives find that they are not in a position to make decisions about care in connection with life-shortening disease.

Adapted information

Laws, who interviewed the caregivers of late-stage cancer patients, confirms the need for early, regular information and planning for the future by means of advanced care planning. This reduced the anxiety and uncertainty of caregivers and strengthened their coping strategies (38). Relatives interviewed by Hunstad wanted health care personnel to take the initiative in discussing and planning in order to reach specific goals, clarify the role of the caregiver and ensure 24-hour health care services and holistic care (24).

Bøckmann emphasises that early involvement and targeted advanced care planning can create trust and clarify the needs of relatives (13). According to Brenne and Estenstad, access to palliative home care services, social support and the expertise of health care personnel are key factors in making provision for dying at home (2). Heath care personnel should therefore provide relevant information and take the initiative to carry out advanced care planning as early as possible so that patients and their relatives can make qualified decisions that can be embedded in an individual care plan.

The dialogue the patient and relatives has with the coordinator, treating physician and the health care service is of fundamental importance for teamwork. Palliative care requires interdisciplinary collaboration (1, 15). In a study on an individual care plan in a course of rehabilitation, teamwork in the planning process was a tool for flexible collaboration (17).

Good interdisciplinary teamwork in connection with an individual care plan can ensure the transfer of information and coordinated, targeted services, as confirmed by Nordsveen and Andershed’s study (39). An individual care plan can promote the involvement of relatives, create structure and highlight resources, so that relatives have an action tool in an uncertain future. According to Antonovsky, this reinforces their coping ability (27).

An individual care plan reinforces the ability to cope

The Norwegian Directorate of Health stresses that an individual care plan is vital for user involvement in a patient pathway (1). Involving patients and their relatives in decisions about their own future can help them to cope better with the situation. Wilson confirms how important relationships are in securing user involvement and independence of choice (autonomy) in a person-centred palliative practice (40).

Breimo et al. write that the individual care plan requires an approach characterised by reciprocal enthusiasm (4). Mutual respect, dialogue and joint decisions were of fundamental importance in strengthening user involvement in Rise’s study (36). A study of people who were chronically ill in the Netherlands revealed that the individual care plan contributed to a more person-centred, planned and inclusive collaboration than if no such plan existed (41).

Person-centred care is central to McCormack and McCance’s nursing model (42). The model emphasises individually adapted services, therapeutic relationships and user involvement, and is based on values such as respect and autonomy. ‘What is important to you?’ is a vital question in person-centred care. A person-centred relationship underpins the work on the individual care plan in which the nurse often plays a key role as a facilitator and coordinator.

Discussion of method

Although the study was conducted in 2011 prior to the entry into force of the new Act and regulations, the findings are still relevant and have been examined in light of new legislation and research. The objective of the study was to gain insight and knowledge about a topic on which there is little research. The multi-stage focus group design functioned as planned because new topics promoted fresh reflections and a deeper understanding. An example is the strain relatives experience when they are involved in the decision to terminate life-prolonging treatment.

The sample was representative although one weakness was that only women were recruited. The sampling criterion was that relatives had been involved in the individual care plan process at the palliative stage. One man and one woman withdrew from the study before the first focus group interview.

Another weakness was that one of the individual plans was only established one week before the patient’s death. According to Hummelvoll (30), groups of 5–8 participants are preferable in multi-stage focus groups, and one group is sufficient.

The strength of the study is that the two focus groups have described shared experiences, for example the importance of hope and dignity, independently of each other. Although the sample is small, the findings of the study can be transferred to similar contexts. In retrospective studies, informants may recall experiences differently. The study has put emphasis throughout the process on answering the research questions.

Conclusion

Our study shows that the individual care plan process at the palliative stage can help relatives to cope better. The informants experienced hope, being seen, less responsibility, involvement and support in a challenging everyday life. The planning process activated resources, established structure, created meaning and coherence.

The coordinator and the individual care plan ensured user involvement by identifying the goals, roles and choices of patients and relatives at the end of life. The health care services emerged as a holistic, coordinated and coherent service in which the flow of information was strengthened.

Nevertheless, our study shows that individual procedures must be quality assured. In order to strengthen user involvement and collaboration with relatives, individual care plans must be established at an early stage of palliative care. Clarifying important questions about treatment and the future can relieve the burden of relatives.

The health care services should initiate advanced care planning so that important decisions can be embedded in the individual care plan. By strengthening relatives’ coping abilities, the health care services make provision for a better end of life at the palliative phase.

There is a need for further research on factors contributing to the work on an individual care plan at the palliative stage and the collaboration of relatives.

In order to achieve individually adapted, coordinated services and the use of an individual care plan in a patient pathway, a person-centred approach is fundamental. A person-centred, balanced approach and the use of an individual care plan requires a change of attitudes in the health care services.

Many thanks to the informants who shared their life experiences and to the health care personnel who helped to find informants. I would also like to thank Kristin Ådnøy Eriksen, Gerd Bjørke and Geir Sverre Braut for critical and constructive feedback on the text in the ongoing process.

References

1. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonalt handlingsprogram med retningslinjer innen palliasjon i kreftomsorgen. 2015;IS-2285.

2. Brenne AT, Estenstad B. Hjemmedød. I: Kaasa S, Loge H (eds). Palliasjon: Nordisk lærebok (2. ed.). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2016 (p. 161–71).

3. Milberg A. Närstående vid palliativ vård. I: Strang P, Beck-Friis B (eds). Palliativ medicin och vård Stockholm: Liber; 2012 (p. 144–51).

4. Breimo JP, Normann T, Sandvin JT, Thommesen H. Individuell plan. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2015.

5. Kjellevold A. Retten til individuell plan (4. ed.). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2013.

6. Helsedirektoratet. Rapport om tilbudet til personer med behov for lindrende behandling og omsorg mot livets slutt – å skape liv til dagene. 2015;02.

7. Meld. St. 26 (2014–2015). Fremtidens primærhelsetjeneste – nærhet og helhet. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-26-2014-2015/id2409890/(downloaded 24.04.2017).

8. NOU 2011:17. Når sant skal sies om pårørendeomsorg. Fra usynlig til verdsatt og inkludert. Norges offentlige utredninger 2011;17.

9. Helsedirektoratet. Veileder om pårørende i helse- og omsorgstjenesten. 2015;IS-2587.

10. Lunde SAE. Individuell plan – ein plan for eit verdig liv. Masteroppgåve. Volda: Høgskulen i Volda; 2012.

11. Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. Forskrift om habilitering og rehabilitering, individuell plan og koordinator. 2011;1256.

12. Lov av 2. juli 1999 om pasient- og brukerrettigheter (pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63(downloaded 26.09.2017).

13. Bøckmann K, Kjellevold A. Pårørende i helse- og omsorgstjenesten – en klinisk og juridisk innføring (2. ed.). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2015.

14. Nilssen E. Kommunal iverksetting av retten til individuell plan. Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 2011;14(2):79–94.

15. Kaasa S, Loge JH. Palliativ medisin – en innledning. I: Kaasa S, Loge JH (eds.). Palliasjon – nordisk lærebok (2. ed.). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2016 (p. 34–50).

16. Humerfelt K. Brukermedvirkning i arbeid med individuell plan. (Doktoravhandling). Trondheim: Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet, Fakultet for samfunnsvitenskap og teknologiledelse, Institutt for sosialt arbeid og helsevitenskap; 2012.

17. Alve G, Madsen VH, Slettebø Å, Hellem E, Bruusgaard KA, Langhammer B. Individual plan in rehabilitation processes: a tool for flexible collaboration? Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 2012;15(2):156–69.

18. Holum LC. “Individual plan” in a user-oriented and empowering perspective: A qualitative study of “individual plans” in Norwegian mental health services. Nordic Psychology 2012 03/01;64(1):44–57.

19. Sægrov S. Sjukepleiarens arbeid med individuell plan for kreftramma. Sykepleien Forskning 2015;10(1):54–61.

20. Fjose M, Eilertsen G, Kirkevold M, Grov EK. A Valuable but Demanding Time Family Life During Advanced Cancer in an Elderly Family Member. ANS 2016 Oct;39(4):358–73.

21. Bollig G, Gjengedal E, Rosland JH. They know! – Do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives views on advance care planning, end-of-life care, and decision-making in nursing homes. Palliative Medicine 2016;30(5):456–70.

22. Sørhus GS, Landmark BT, Grov EK. Ansvarlig og avhengig – pårørendes erfaringer med forestående død i hjemmet. Klinisk sygepleje 2016;43(2):87–100.

23. Grøthe Å, Biong S, Grov EK. Acting with dedication and expertise: Relatives’ experience of nurses’ provision of care in a palliative unit. Palliative Supportive Care 2015 12;13(6):1547–58.

24. Hunstad I, Svindseth MF. Challenges in home-based palliative care in Norway: a qualitative study of spouses’ experiences. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2011;17(8):398–405.

25. Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19(10):1013–25.

26. Hanssen S. Lindring av lidelse mot livets slutt – et pårørendeperspektiv. (Master's thesis). Göteborg: Nordiska högskolan för folkhälsovetenskap; 2006.

27. Antonovsky A. Helbredets mysterium. København: Hans Reitzel Forlag; 2000.

28. Heggen K. Rammer for meistring. I: Ekeland TJ, Heggen K (eds.). Meistring og myndiggjering Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2007 (p. 64–82).

29. Lindseth A, Norberg A. A phenomenological hermeneutical method for researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci 2004;18(2):145–53.

30. Hummelvoll JK. Multi-stage focus group interview: a central method in participatory and action-oriented research designs. Klinisk sygepleje 2010 07;24(3):4–13.

31. Wibeck V. Fokusgrupper – om fokuserade gruppintervjuer som undersökningsmetod. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2010.

32. Malterud K. Fokusgrupper som forskningsmetode for medisin og helsefag. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2012.

33. Wold KB, Rosvold E, Tønnesen S. «Jeg må bare holde ut...» Pårørendes opplevelse av å være omsorgsgiver for hjemmeboende kronisk syke pasienter – en litteraturstudie. In: Tønnesen S, Kassah B (eds.). Pårørende i kommunale helse- og omsorgstjenester – forpliktelser og ansvar i et utydelig landskap Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2017 (p. 52–78).

34. Stensheim H, Hjermstad MJ, Loge JH. Ivaretakelse av pårørende. In: Kaasa S, Loge JH (eds.). Palliasjon: Nordisk lærebok (2. ed.). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2016 (p. 274–86).

35. Alidina K, Tettero I. Exploring the therapeutic value of hope in palliative nursing. Palliative & Supportive Care 2010;8(3):353–8.

36. Michael N, O’Callaghan C, Baird A, Hiscock N, Clayton J. Cancer Caregivers Advocate a Patient- and Family-Centered Approach to Advance Care Planning. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2014;47(6):1064–77.

37. Gawande A. Quantity and Quality of Life – Duties of care in Life-Limiting Illness. American Medical Association 2016;315(3):267–9.

38. Laws RF. Evaluating the perceptions of quality of life in informal caregivers caring for hospice patients. (Ph.d. thesis). Hattiesburg: University of Southern Mississippi; 2014.

39. Nordsveen H, Andershed B. Pasienter med kreft i palliativ fase på vei hjem – sykepleieres erfaringer med samhandling. Nordisk sygeplejeforskning 2015;5(3):239–52.

40. Wilson F, Ingleton C, Gott M, Gardiner C. Autonomy and choice in palliative care: time for a new model? J Adv Nurs 2014 05;70(5):1020–9.

41. Jansen DL, Heijmans M, Rijken M. Individual care plans for chronically ill patients within primary care in the Netherlands: Dissemination and associations with patient characteristics and patient-perceived quality of care. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 2015;33:100–6.

42. McCormack B, McCance T. Underpinning principles of person-centred practice. In: McCormack B, McCance T (red). Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom: WILEY Blackwell; 2017 (s. 13–35).

Comments