Newly qualified midwives in Norway and adverse events at work

Summary

Background: Midwives are key personnel in the health service. There is a known shortage of midwives in Norway. Midwives’ job satisfaction affects the quality of care provided to pregnant women and their families.

Objective: To explore the characteristics of newly qualified midwives who experience adverse events at work, the coping strategies they employ and their reactions in the aftermath of such events. The aim of the study was also to map what follow-up newly qualified midwives reported receiving from their employer, as well as their wishes for follow-up after adverse events at work.

Method: This is a cross-sectional study conducted in Norway. A total of 125 newly qualified midwives who graduated between 2018 and 2023 responded.

Results: The findings show that 42% of newly qualified midwives had either quit or considered quitting their job as a midwife. High workload, the burden of shift work and low staffing levels were cited as the main reasons for quitting or considering quitting. Coping strategies after adverse events included debriefing with colleagues and talking to friends and family. Midwives who had quit or considered quitting were more likely to have changes in duties or departments, a higher incidence of burnout, and a feeling of not being suited for the job. Regardless of whether they had considered quitting or not, nearly 70% reported experiencing physical stress reactions when reminded of adverse events they had faced. In total, over 40% of newly qualified midwives said they did not know whether follow-up guidelines existed at their workplace. More than 70% either agreed or strongly agreed that changes are needed in the follow-up after adverse events at work.

Conclusion: The study’s findings show that newly qualified midwives experience physical reactions and consider leaving the profession after adverse events at work. Furthermore, the findings point to a need for employers to work with midwives to develop guidelines and a clear follow-up plan in connection with adverse events at work.

Cite the article

Bergland A, Molden C, Aanensen E, Vik E. Newly qualified midwives in Norway and adverse events at work. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(99423):e-99423. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.99423en

Introduction

Midwives play an important role in the health service (1, 2). Their well-being and sense of security in the workplace affect the quality of care they provide to pregnant women and their families (3, 4).

Women report a more positive birth experience and a greater sense of security when supported by a midwife throughout the entire birth process. This can influence the use of pain relief (3, 5) and birth outcomes, such as fewer caesarean sections and fewer interventions (3, 6).

However, there is a known shortage of midwives, and the Norwegian Health Personnel Commission has estimated a shortfall of 600 full-time midwife positions by 2040 (7). Moreover, it is not uncommon for midwives to experience traumatic births or other adverse events at work (8, 9), which may help explain why some leave clinical positions.

Some pregnant women have complex health needs. Maternal age is higher than before and an increasing proportion are immigrants, which underscores the need to strengthen midwifery capacity in Norway (1).

However, the Norwegian Directorate of Health reports that one in five midwives have considered leaving the profession (2). A recent report from the National Audit Office of Norway shows that the capacity of midwifery education programmes in Norway is lower than the demand. Staffing challenges are increasing, and long-term staffing shortages can have serious implications for the service provision (10).

If the health service provides good support for newly qualified midwives, they are more likely to remain in the profession longer. This is important in light of the current shortage of midwives, limited educational capacity and lack of clinical placements (1, 2).

A systematic review examining how adverse events affect midwives and nurses highlights the need for a stronger focus on these occupational groups in order to strengthen their ability to cope with adverse events at work and to regain the professional confidence needed to stay in the profession (9).

Studies from Norway, Sweden and Turkey have shown that one in five or more midwives develop symptoms of burnout (11, 12) and that many midwives and nurses in the field report symptoms of post-traumatic stress following adverse events at work (13–15).

The findings are supported by a British study, which concluded that midwives who experienced traumatic events at work also reported symptoms of burnout and stress (16).

An Italian study found that midwives are at increased risk of burnout after just five years in the profession (17). It also identified an association between burnout and exposure to stressful events, particularly among midwives who had been involved in stillbirths (17).

A Swedish study also shows that midwives working shifts and with little experience are particularly vulnerable to burnout (18).

A Dutch cross-sectional study investigated the prevalence of potentially traumatic events in the workplace, health-related symptoms and support systems among paediatricians, gynaecologists and orthopaedic surgeons (19).

The study concluded that these groups are frequently exposed to events with a high emotional impact over the course of their career (19). A lack of guidelines for follow-up and support after traumatic events was associated with an increased incidence of post-traumatic stress among employees (19).

The Dutch study did not include midwives (19), an occupational group in Norway that often encounters the same traumatic events described in the study. We based our work on the validated questionnaire used in the Dutch study (19) and conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the characteristics of newly qualified midwives in Norway who experience adverse events at work.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to examine the coping strategies used by newly qualified midwives and their reactions following adverse events at work. We were particularly interested in differences between those who had considered leaving or had already left the profession and those who chose to stay.

The study also mapped the follow-up that newly qualified midwives received and would like to receive from their employer.

Method

This is a cross-sectional study. Participation was open between 13 November and 4 December 2023 via the website nettskjema.no. We used the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies to quality assure this article.

Adverse events

It is uncertain how to best define an adverse event in obstetrics and how common it is to experience adverse events at work as a midwife (9). In this study, the participants themselves defined what they considered to be an adverse event at work.

Sample

The sample in our study was recruited through self-selection and snowball sampling (20). The study includes newly qualified midwives in Norway who graduated between 2018 and 2023.

Recruitment

A poster with information about the study was posted in the Facebook group ‘Midwives in Norway’ (Jordmødre i Norge). At the time of recruitment, the group had 3100 members. We also contacted the administrators of 20 Instagram accounts representing various maternity units in Norway.

Additionally, we contacted the Norwegian Midwives Association and the NSF Midwives Union in the hope that they could distribute the survey to their members. The NSF Midwives Union declined the request due to lack of capacity.

One week after starting recruitment, we found that the study had few respondents from certain regions. We therefore posted a new message in the Facebook group ‘Midwives in Norway’, encouraging members to share the survey with midwives from underrepresented areas.

The mailrooms at all health trusts in Norway were also emailed information about the study, with a request to forward the study information to the maternity units in their region.

Devising the questionnaire

The questionnaire used in this study was based on part of a validated questionnaire aimed at gynaecologists in a Dutch cross-sectional study (19). The final questionnaire used in our study consisted of 25 questions (Appendix 1 – only in Norwegian).

The appendix shows which questions were inspired by the Dutch study (n = 17) (19) and the Swedish study (n = 2) (14), and which were specifically developed for our study (n = 6). All questions included were carefully selected based on their relevance to the study's objectives.

The questions from the Dutch study were translated into Norwegian using a four-step process described by Tsang et al. (21). In the first step, the English questionnaire was translated into Norwegian. In the second step, the Norwegian version was translated back into English.

In the third step, the questionnaire was adapted to midwifery. We also contacted the first author of a research article based on a Swedish study in which the authors had investigated post-traumatic stress reactions in midwives and gynaecologists (14).

The authors of this study received the validated questionnaire from the Swedish study by post. We included two of the questions from the Swedish questionnaire in order to better address the aims of our study (14).

Finally, we formulated six questions that were unique to this study. We conducted a pilot study as part of the fourth and final step in the quality assurance of the final questionnaire (21).

We then pilot-tested the survey with 14 midwives and midwifery students who did not meet the study’s inclusion criteria. Feedback from the pilot study regarding the response options was taken into account in the final version of the questionnaire.

Collected data

This study included the following background characteristics: age group (24–34 years, 35–44 years, 45 years and older), region (Northern Norway, Trøndelag, Western Norway, Eastern Norway, Southern Norway), workplace (primary health service, specialist health service, non-clinical, private practice, non-midwifery work, other, free text), change of department or duties after adverse events (yes, no), and adopting a more cautious approach (agree/strongly agree, disagree/strongly disagree).

We collected data on whether the midwives in the study had considered leaving the profession (yes, no, already left). We also collected their descriptions of what they defined as adverse events (critical situations involving risk to life, deaths of pregnant women, women in labour, postpartum women, or newborns, overlooked risk factors, inability to help patients, uncertainty about whether you made the right decision, feelings of guilt, negative reactions from parents, being left to their own devices, other, free text).

Reasons given for quitting or considering quitting their job were also collected (pressure of work, adverse events, low pay, lack of autonomy, understaffing, medicalisation, the burden of shift work, non-work-related challenges, other, free text), as well as reasons for staying in the profession (job satisfaction, working environment, variety, other).

We also collected information about the midwives’ coping strategies following adverse events (not applicable, continuing as before, seeking professional help, going home as soon as possible, drinking more alcohol, smoking more cigarettes or using more snus, taking medications or drugs, finding a distraction, religious activities, formal case review, debriefing, working out or doing a hobby, talking to friends or family, sick leave, quitting, other).

Physical reactions were also mapped (burnout symptoms, thoughts about personal suitability, stress reactions, feelings of guilt).

In addition, we collected data on perceived support (lack of support from manager, colleagues, friends or partner, negative debriefing, feeling of being talked about behind one’s back), follow-up guidelines (yes, no, don’t know), follow-up after the event (debriefing by management, informal conversations with manager), and desired changes in practice (access to a psychologist, occupational health service for debriefing, temporary accommodations, cautious discussion in group sessions, one-on-one conversation with manager, more management involvement).

Free-text responses from the survey are attached (Appendix 2 – only in Norwegian).

Analysis

Based on concerns about a growing shortage of midwives in Norway, the material in the study was divided into two groups: those who had left or were considering leaving the profession as a midwife (n = 50), and those who were not considering leaving the profession (n = 69).

This division made it possible to identify risk factors, resources and coping strategies that may be effective in supporting newly qualified midwives early in their careers.

The results are presented as absolute numbers, percentages and p-values. The variables in this study are categorical. To assess differences between the groups, we used Pearson’s chi-square test. The null hypothesis (H0) was that there were no significant differences between the groups studied, while the alternative hypothesis (Ha) indicated a possible difference.

P-values were reported to evaluate the validity of H0 (22). In line with common practice in studies calculating p-values, the significance level was set at p < 0.05. By comparing midwives who had either left or were considering leaving with those who were not considering it, the aim was to identify any differences between the groups.

We analysed the data using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.0.0 and Microsoft Excel version 2307.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (23) and was deemed not subject to review by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK), in accordance with section 2 of the Health Research Act (reference number 674038, REK North).

The data in the project were stored and handled in accordance with UiT The Arctic University of Norway’s guidelines for secure storage, collection and processing (24). The information and consent form were prepared using a template from Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research.

The survey was anonymous, and respondents could withdraw at any time before submitting the questionnaire.

Results

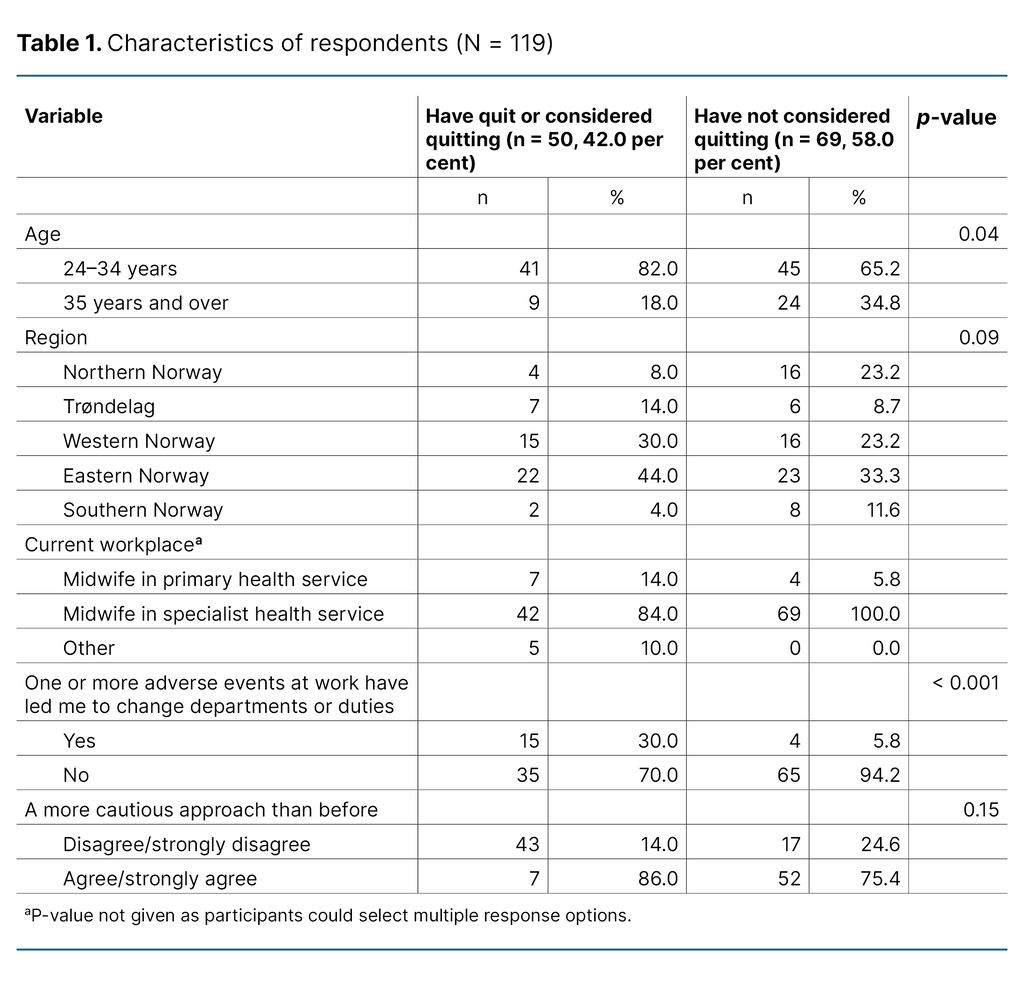

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the respondents. Of the 119 newly qualified midwives included in the study, 42.0% reported that they had either left (n = 3) or were considering leaving (n = 47) the midwife profession.

Among those who were not considering leaving, a greater proportion were aged 35 or over (p-value < 0.04) compared to the group of midwives who had left or were considering leaving. Regardless of whether the midwives were considering leaving or not, the largest group of respondents were from Eastern Norway, followed by Western Norway and Northern Norway.

The midwives had the option to select more than one current workplace from the categories ‘primary health service’, ‘specialist health service’ and ‘other’.

Table 1 shows that the majority of newly qualified midwives worked in the specialist health service. Among those who had left or were considering leaving, 84.0% worked in the specialist health service. All those who were not considering leaving worked in the specialist health service.

The group of midwives who had quit or were considering quitting their job changed departments or duties more frequently (p-value < 0.001) compared to the group who were not considering quitting.

A considerable proportion agreed or strongly agreed with the question of whether they had adopted a more cautious approach to their work: of those who had quit or were considering quitting, 86.0% agreed. In the group not considering quitting, 75.4% agreed.

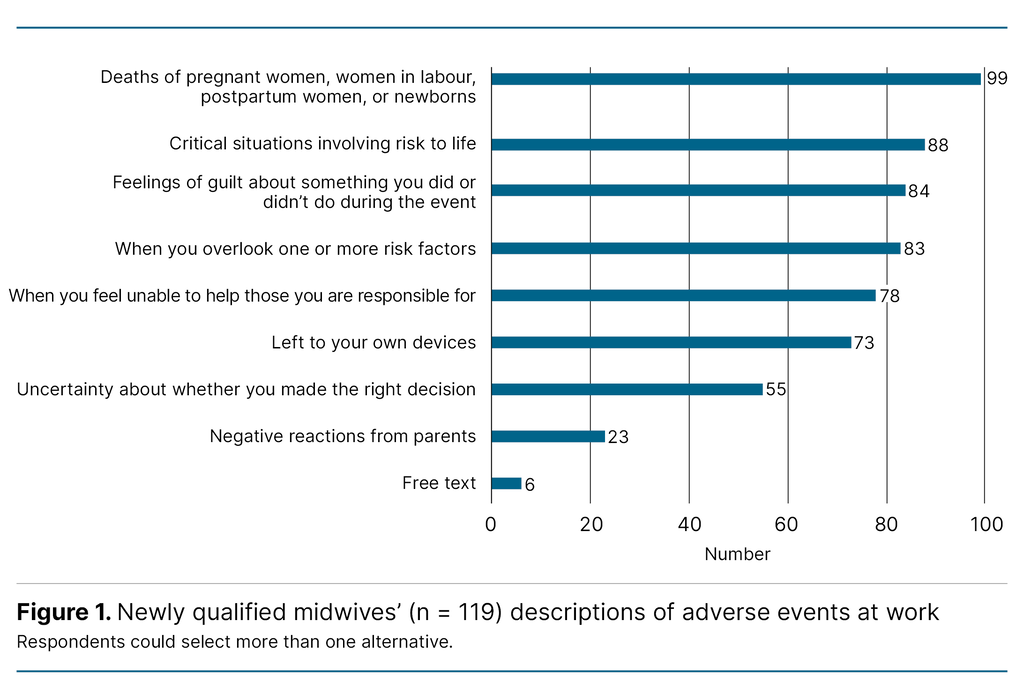

Figure 1 shows the types of events that the newly qualified midwives defined as adverse events related to their work. Maternal and perinatal deaths or situations where lives were at risk were the most commonly reported types of adverse events identified by participants in relation to their work.

In addition to predefined categories, the midwives provided the following free-text responses (n = 6) when asked what they would describe as an adverse event in relation to their work:

‘When the person on duty/responsible midwife seems dissatisfied with my work’, ‘Negative comments from more experienced midwives’, ‘When I am sent around different departments without training in those departments’, ‘Not being able to meet patients’ needs due to staffing or budget constraints; closed delivery rooms’, and ‘Neonatal asphyxia, leading to the baby requiring therapeutic hypothermia’.

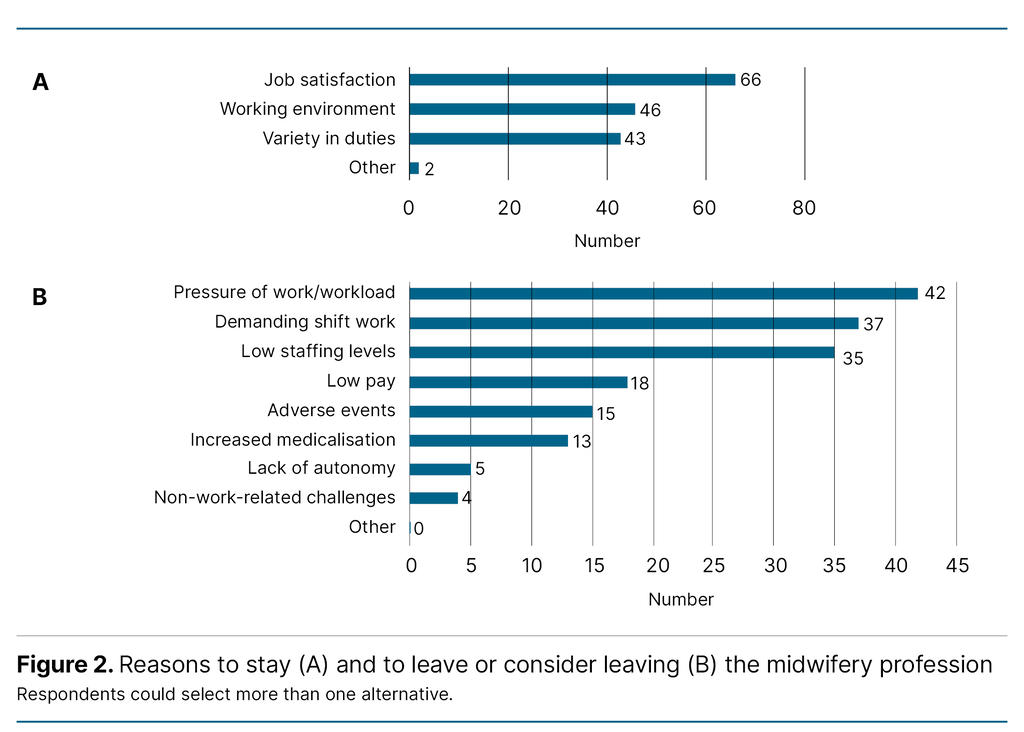

Figure 2 shows the reasons midwives gave for not quitting the profession (A), or for quitting or considering quitting the profession (B). Job satisfaction (n = 66) was the most common main reason for staying in the profession. The dominant reasons midwives gave for considering quitting their job included pressure of work or workload (n = 42), the burden of shift work (n = 37) and low staffing levels (n = 35).

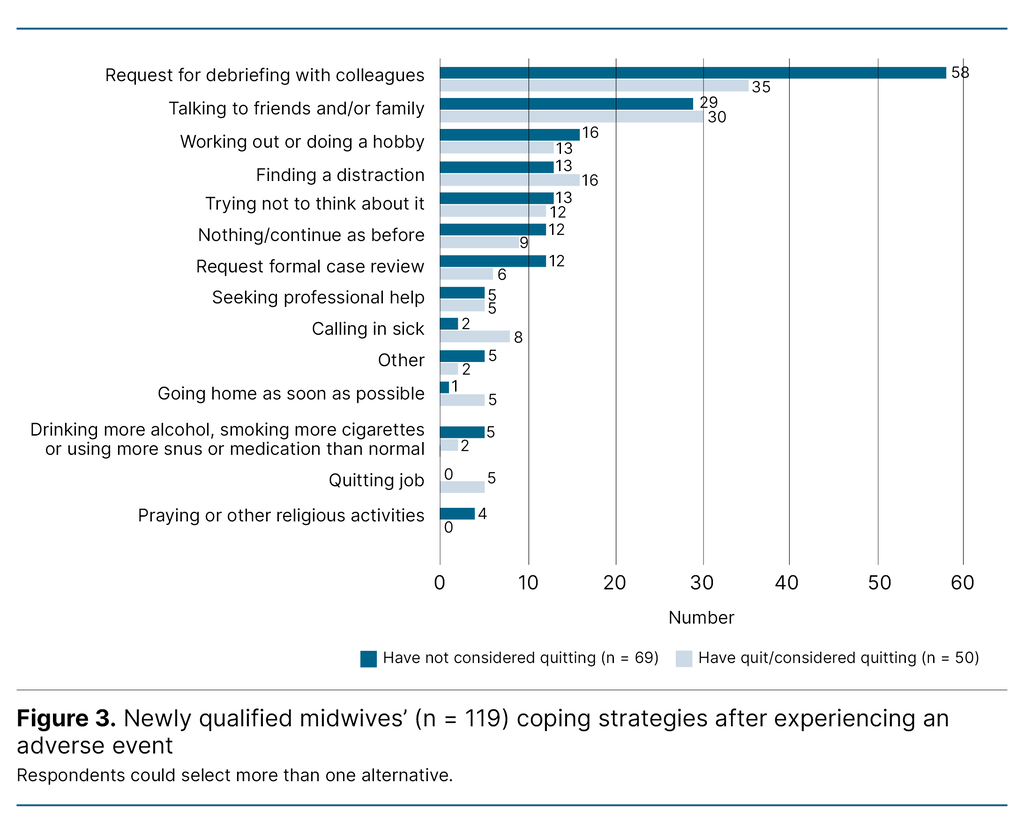

After experiencing adverse events at work (Figure 3), the majority in both groups requested debriefing with colleagues (n = 58 and n = 35), followed by talking to friends or family (n = 29 and n = 30), and working out or doing a hobby (n = 16 and n = 13).

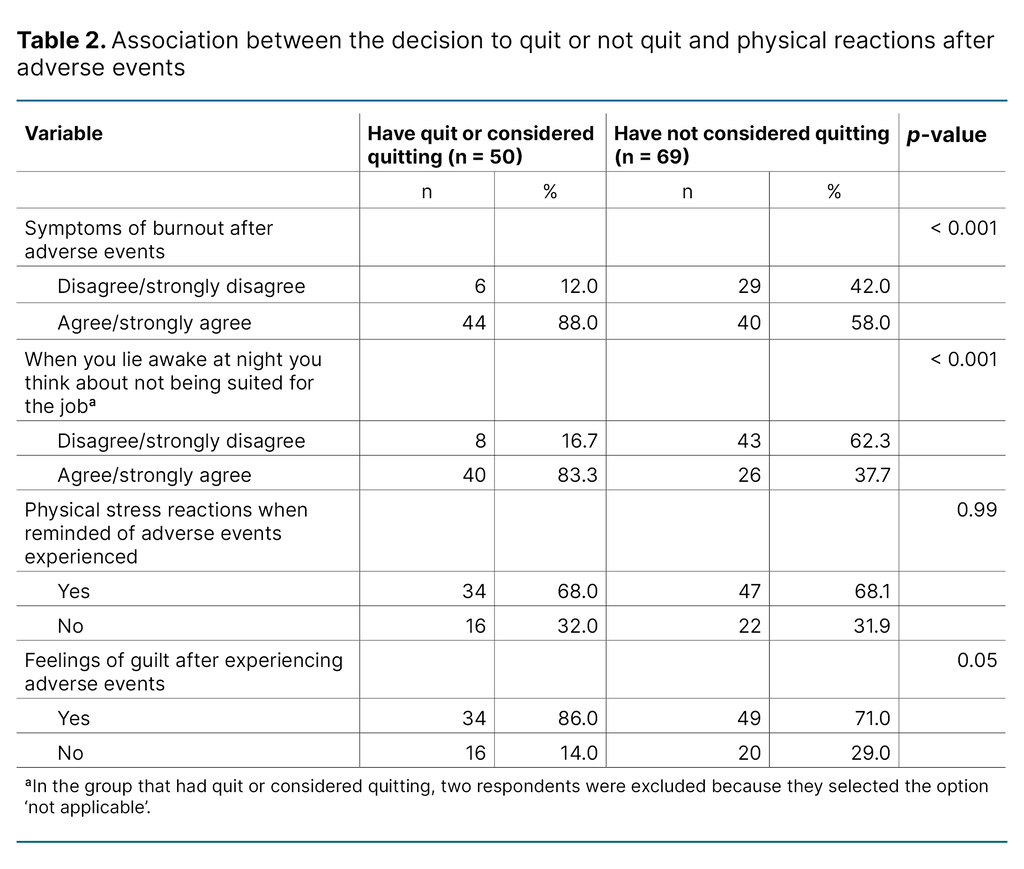

Table 2 presents the physical reactions of those who had quit or were considering quitting, compared with those who were not considering quitting. Midwives who had quit or were considering quitting experienced symptoms of burnout to a greater extent (p-value < 0.001) and were more likely to question their suitability for the job (p-value < 0.001) than those who were not considering quitting.

Midwives who had quit or were considering quitting (68.0%) as well as those who were not considering quitting (68.1%) reported experiencing physical stress reactions when reminded of adverse events they had faced.

When asked about feelings of guilt after adverse events, 86.0% of those who had quit or were considering quitting and 71.0% of those who were not considering quitting said they had felt this way.

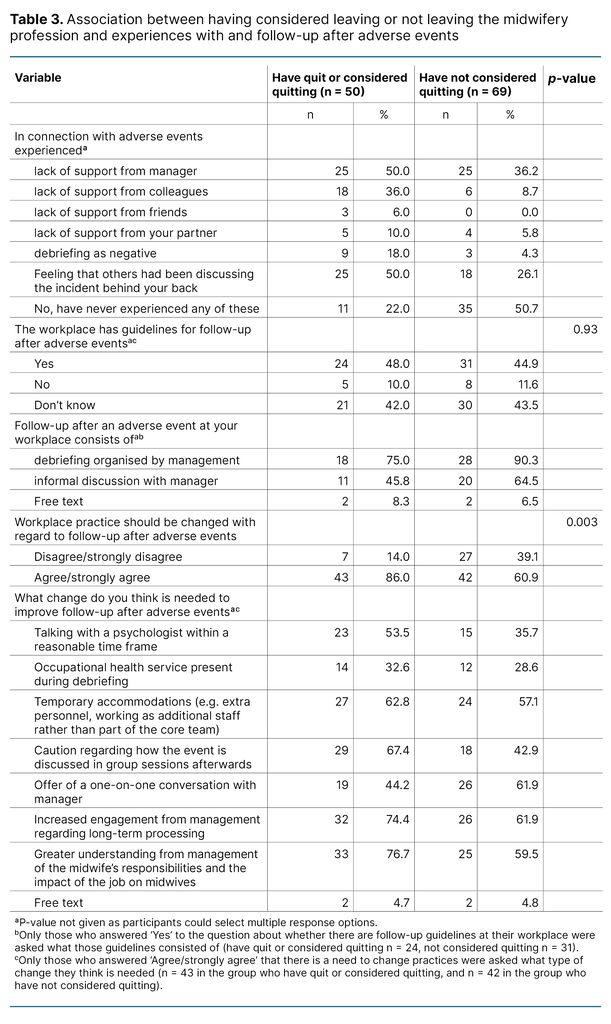

In connection with adverse events, it emerged that the midwives who had quit or were considering quitting the profession had experienced a lack of support from their manager (50.0%) and a feeling that others had been discussing the incident behind their back (50.0%).

Several in the group who were not considering quitting experienced neither of these (50.7%) (Table 3).

Overall, 46.2% of the newly qualified midwives (48.0% in the group who had quit or were considering quitting, 44.9% in the group who were not considering quitting) reported that their workplace had guidelines for follow-up related to adverse events. Such follow-up mainly consisted of debriefing organised by management (75.0% in the group who had quit or were considering quitting, 90.3% in the group who were not considering quitting).

A greater proportion of those who had quite or were considering quitting agreed or strongly agreed that follow-up after adverse events at the workplace should be improved, compared to those not considering quitting (p = 0.003).

The midwives who had quit or were considering quitting responded that the following factors were important for improving follow-up: greater understanding from management of the midwife’s responsibilities and the impact of the job on midwives (76.7%), increased engagement from management regarding long-term processing (74.4%), and caution when discussing incidents in group sessions (67.4%).

The group who were not considering quitting highlighted the offer of a one-on-one conversation with their manager (61.9%) and greater engagement from management regarding long-term processing (61.9%) as the most important measures for improving follow-up, followed by greater understanding from management of the midwives’ responsibilities and the impact of the job on them (59.5%).

Discussion

The findings of this study show that good working conditions and a positive working environment are important for newly qualified midwives who wish to continue in the profession. A large proportion (42%) of the newly qualified midwives in our study had left or were considering leaving the profession.

Reasons for wanting to leave the profession included high workload, demanding shift work and low staffing levels. More of those who had either quit or were considering quitting reported having changed department or duties, increased burnout and feelings of inadequacy than those who were not considering quitting.

Regardless of whether the midwives were considering quitting or not, nearly 70% reported experiencing physical stress reactions when reminded of adverse events they had faced.

Coping strategies after adverse events at work included debriefing with colleagues and conversations with friends and family.

Furthermore, this study shows that over 40% of respondents were uncertain about existing guidelines for follow-up after adverse events in the workplace, while over 70% expressed a desire for changes in how such events were handled.

Good working conditions and a positive working environment were identified as important factors for newly qualified midwives wanting to remain in the profession. This finding aligns with results from other studies (25–27).

Nearly half of the newly qualified midwives in our study were considering leaving the profession or had already left. Common reasons included high workload, demanding shift work and low staffing levels. Newly qualified midwives should have a long career ahead of them (2).

However, studies show that young midwives are overrepresented among those considering leaving the profession (25, 28). A recent exploratory review highlights that midwives often leave the profession due to factors such as job-related stress, the burden of shift work and lack of support from management or colleagues (25).

An Australian study shows that midwives tend to stay in the profession if they have good relationships with colleagues and are passionate about their work (26). A review article, which also includes the Australian study, adds that midwives are likely to remain in the profession if they enjoy their job, have professional pride, satisfactory pay and flexibility regarding voluntary part-time working (27).

Furthermore, studies from Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom show that young midwives with little work experience appear to have a particularly high risk of work-related stress and burnout compared to their older colleagues (12, 18, 29).

To retain newly qualified midwives in the profession, it is important to examine the reasons why they might want to leave. The reasons highlighted in this study align with findings from a study in Australia (30) and a report from the National Audit Office of Norway which showed that high workload is a typical reason why midwives and nurses work part time (31).

High workload can partly be explained by the fact that an increasing number of pregnant women have complex health needs. Reasons include older maternal age and an increasing proportion of immigrants (1, 32, 33), which affect both staffing and financing (1).

Our study shares many similarities with other Norwegian studies (34, 35). It shows that there is a need to implement measures to reduce workload and involuntary part-time working, evaluate shift rotas and improve baseline staffing to retain midwives in the profession.

A Norwegian study adds that opportunities for professional development and good relationships with other occupational groups are important factors for staying in the profession (34). Intervention studies are needed to test the effect of the various measures.

Debriefing is a coping strategy

One of the findings of this study was that coping strategies after adverse events included debriefing with colleagues and talking to friends or family. This finding is consistent with a 2020 systematic review, which shows that midwives and nurses seek support from colleagues, management, family and friends after experiencing adverse events at work (9).

Debriefing with those closest to them, both at work and in their personal lives, has been identified as an important factor in processing complex and difficult events. The systematic review further shows that the absence of formal debriefing following an adverse event can have a negative impact on professional confidence and contribute to staff leaving their jobs (9).

Many want better follow-up in the workplace

In 2024, the Norwegian Directorate of Health published a guide for the follow-up of patients, their families and employees after adverse events. The aim is to promote a culture of support, openness and learning in the health service (36). The guide emphasises how a systematic approach and peer support are key elements in the follow-up of employees after adverse events (36).

An exploratory review article from 2023 found that midwives often consider leaving the profession due to lack of support and dissatisfaction with the working environment (25). Experiences from various peer support arrangements were also compiled in a report published the same year (37).

A large proportion of the newly qualified midwives in our study reported that they did not know whether guidelines for follow-up existed in their workplace. More than one in three midwives said they wanted changes in how follow-up after adverse events at work is handled.

The systematic review article mentioned above also showed that follow-up after adverse events varied across workplaces, and the arrangements in place were described as ranging from satisfactory to completely non-existent (9).

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is small, and the results should be interpreted with caution. Respondents (n = 6) who had not experienced adverse events at work were excluded due to potential selection bias, as the wording of the invitation may have appealed more to those who had had such experiences.

However, the six excluded respondents would have represented 5.0% of the sample, which corresponds to the proportion reported in an Israeli study, where 94.3% of midwives had been present at a traumatic birth (8).

To minimise the risk of information bias, we based our study on validated questionnaires. However, some of the original response options were changed from a gynaecology context to a midwifery context, and we added questions of our own.

One limitation of the study is the variations in the definitions and understandings of the terms ‘adverse events’ and ‘traumatic births’ (9).

In our study, the term ‘adverse events’ covers a broad range, from life-threatening situations to negative reactions and emotions. Future studies should consider specifying the types of adverse events being investigated to make it easier to compare results across studies.

Conclusion

The results of the study show that newly qualified midwives experience physical reactions and consider leaving the profession after adverse events at work.

The findings also highlight the need for employers to familiarise themselves with national guidelines and work closely with midwives in developing local protocols for follow-up after such events.

Further research is needed to explore the reasons why midwives consider leaving the profession. Intervention studies are also needed to assess the effectiveness of guidelines and various support measures aimed at ensuring that newly qualified midwives receive the support they need to remain in the profession throughout their career, even after experiencing adverse events at work.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the newly qualified midwives who took part in this study. We would also like to thank Ingvild Hersoug Nedberg, associate professor, for her valuable input.

Alise Tamara Bergland and Camilla Molden share first authorship.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments