Being in contact with nature activates memories and offers elderly people in nursing homes beneficial experiences

Nursing home residents are dissatisfied with a sedentary life indoors and reach out more to others socially when they are outdoors. Nevertheless, they have little contact with nature and the outdoor environment.

Background: Earlier research shows that contact with nature can promote well-being in nursing home residents. However, little use is made of nature and the outdoors as therapeutic environments in nursing homes.

Objective: The objective of this study was to explore and describe what characterises experiences and memories linked to nature and the outdoor environment in a Norwegian context for residents staying permanently in a nursing home.

Method: The study had a qualitative exploratory and descriptive design. We collected data using semi-structured interviews. Eight participants aged between 62 and 90 were interviewed twice. We carried out one interview outdoors and one indoors in the resident’s room with the aid of photographs of natural environments, with each participant. The audiotaped interviews were transcribed and analysed using systematic text condensation.

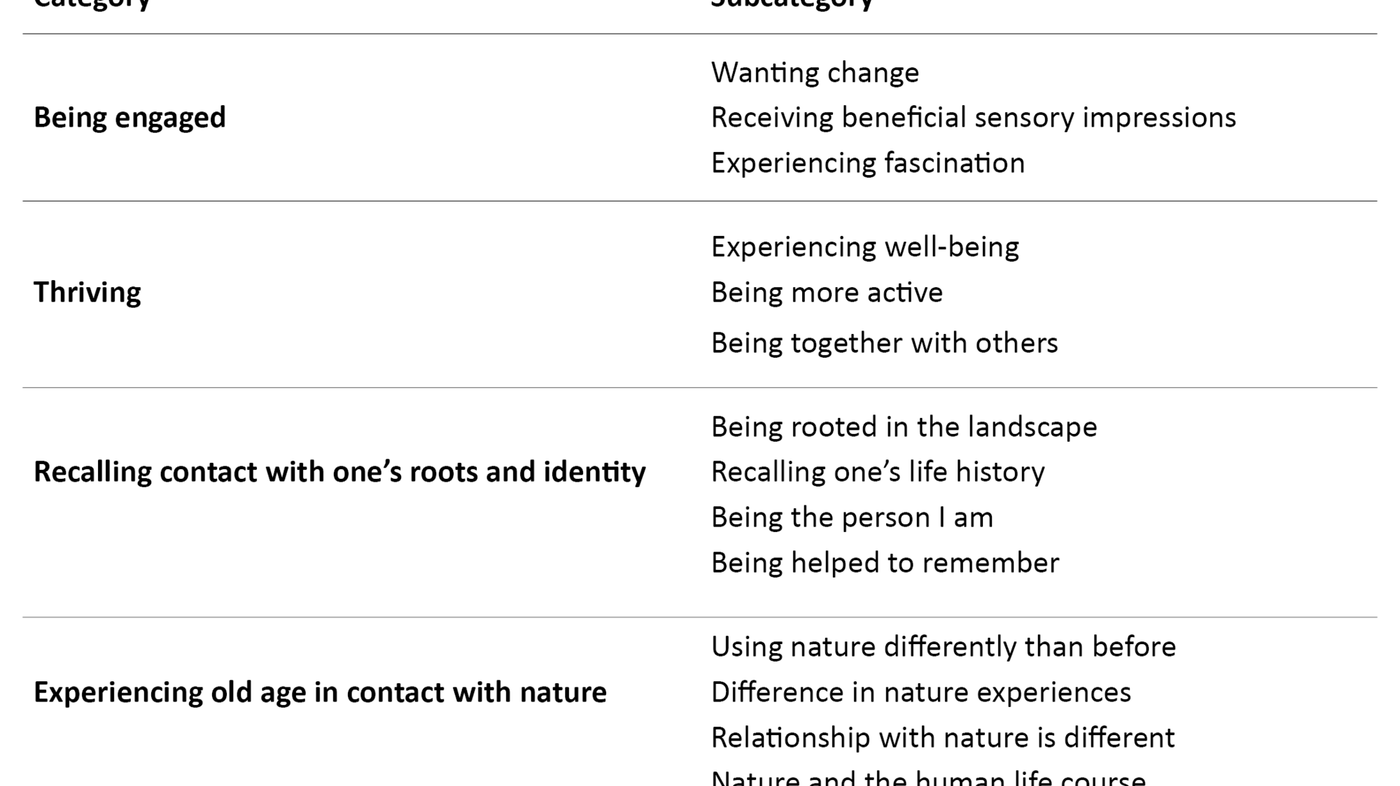

Results: We identified four main themes with sub-groups:

Being engaged: wanting change, receiving beneficial sensory impressions, experiencing fascination

Thriving: experiencing well-being, being more active, being together with others

Recalling contact with one’s roots and identity: being rooted in the landscape, recalling one’s life history, being the person I am, being helped to remember

Experiencing old age in contact with nature: using nature differently than before, difference in nature experiences, relationship with nature is different, nature and the human life course

Conclusion: Residents’ perceptions of nature and the outdoor surroundings are characterised by good experiences and a reactivation of their own life history. Nature and the outdoor surroundings should have a key position as therapeutic environments in nursing homes. The findings are in line with established theories and are supported by reported research in the field.

Elderly people living permanently in nursing homes have little contact with nature. This often entails a significant difference from what they were accustomed to in their earlier years (1). Nature and the outdoor environment have important qualities in promoting well-being, reducing stress, improving cognitive functions and activating good memories. Nevertheless, little use is made of nature, the outdoors, and outdoor activities in the therapeutic use of environments (2, 3), despite the fact that this may significantly affect elderly people’s quality of life (4).

The opportunity to get out of the nursing home ward and take part in meaningful activities is of key importance for thriving (5), happiness, well-being and quality of life (6). Likewise, the ability to concentrate has been reported to be improved in elderly people who regularly spend time outdoors compared with those who primarily remain indoors (7).

A systematic review addressing the benefits of sensory gardens for dementia disorders reports increased well-being, improved sleep, a reduction in serious falls and less use of psychotropic medications (8). A well organised outdoor environment or a sensory garden helps the elderly to get outside and facilitates meaningful conversations (9).

Reminiscence

Nature and gardens provide a multisensory and symbolic environment that can help to recall episodes from a person’s past (10), since different sensory stimuli have the potential to activate memories (11), both referred to as reminiscence. Reminiscence is defined as the process of thinking about or telling others about one’s own past experiences (12).

The process of reminiscence helps to activate memories that promote identity, self-worth and self-perception, which in turn reinforces the feeling of wholeness, coherence (11) and meaning (13). The outdoor surroundings are also important in terms of exposure to daylight (14), participation in enjoyable activities (15) and experiences involving change and freedom (16). In addition, the garden and outdoor surroundings pave the way for social interaction and meaningful conversations (9).

When people are outdoors, both an emotional and an aesthetic response are triggered (17). The emotional response affects perception and cognition, activating a complex interaction of thoughts, feelings, meaningful experiences and memories (17). The aesthetic response is characterised by joy and positive feelings, and may have a stress-reducing effect by blocking worries and negative thoughts (17, 18).

According to the Attention Restoration Theory (ART) developed by Kaplan and Kaplan (19), exposure to and experience with nature can also help to restore attentional functions and reduce mental tiredness. Four qualities of the natural environment are of key importance for the occurrence of these processes:

- The natural environment entails a real change and distance (being away) from one’s ordinary environment.

- The natural environment has the potential to fascinate (fascination).

- The natural environment is extensive enough to be explored and retain engagement over time (extent).

- The natural environment’s qualities must be in accordance with the individual’s interest in nature (compatibility).

A change in the environment from indoors to outdoors thus entails a change in stimuli that permits multisensory perceptions, emotional and aesthetic responses, cognitive engagement, fascination and stress reduction.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to explore in a Norwegian context what characterises experiences and memories linked to nature for nursing home residents, underpinned by the theoretical perspectives presented and earlier research.

Method

Design

The study had a qualitative exploratory and descriptive design where individual semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. We selected three nursing homes situated in rural surroundings as the research context.

Sample

The informants in the study were residents staying permanently in a nursing home. The inclusion criteria were the ability to narrate stories from their own lives and the absence of serious sight or hearing impairment. The informants were recruited by the nursing home director passing on the request to the ward managers who then asked suitable residents if they would like to participate.

Eight residents between the ages of 62 and 90 agreed to take part in the study. Three of these were women. The residents had an average residence time of 3.7 years, with a variation of from one to twelve years.

Collection and analysis of the data

We interviewed all eight residents twice using the same interview guide – once outdoors in the natural environment and once indoors in the patient’s own room. In the outdoor interviews, we focused on the residents’ experiences of the surroundings in a here and now perspective. In the interviews that took place in the resident’s room, we addressed the recalling of memories and the life history of the individual related to nature experiences. In the latter interviews, we used photographs of four different natural environments as a supportive tool since this has proved to be useful in interviews with frail elderly people (20, 21). We conducted altogether 16 research interviews with the eight nursing home residents. The interviews lasted 45 minutes on average, with a total interview time of 7.5 hours. All the interviews were audiotaped.

The activation of the residents’ memories was triggered by the interviewer’s questions, by what the interviewer added, by the photographs accompanied by the interviewer’s questions, and in some cases by the photograph itself. The findings of the interviews outdoors were consistent with the interviews indoors using photographs.

We transcribed the audiotaped recordings and analysed the transcribed material in accordance with Malterud’s method of systematic text condensation (22). This method entails the condensation of meaning units with the ensuing development of categories and subcategories. Our text material coded into categories and subcategories provided the basis for preparing analytical texts that in turn resulted in meaningful descriptions of the different categories in the material.

Ethical issues

We obtained written consent from the residents who participated in the study. The project was approved by the then Norwegian Social Science Data Services, now NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data (project no. 38162).

Results

We present the findings in accordance with the structure used in Table 1. The findings are presented as a summary informed by illustrative statements.

Being engaged

The category ‘being engaged’ was related to a need for change, acquiring good sensory impressions and being fascinated. The wish for change was linked to a longing for engagement since staying indoors was associated with being passive: ‘I find it easy just to put my feet up in my room and not move, and that’s not good.’

‘If I spot a roe deer in a field outside, I feel like going outdoors, but I just can’t manage it.’

The residents appreciated good sensory impressions both indoors and outdoors: ‘That birch tree over there – the tall one – I think it’s so beautiful. Now it’s come into leaf, but the first thing you see are the small green shoots, they’re so pretty.’

‘I like to sit and gaze at the trees from the window, I need to have a glimpse of that.’

Being engaged was related to the experience of fascination and joy inspired by nature: ‘Oh look! There’s Pussy and just look. It’s caught something!’

‘When the birds are in the trees, it’s such fun [voice expresses emotion].’

Thriving

This category accommodates perceptions of well-being, activity and being outdoors together with others. The residents said, ‘I feel more alive in springtime’, and that being able to go outside gave a feeling of freedom: 'It represents freedom, I think it’s wonderful to be outdoors as much as possible.’

Some residents also associated being outdoors with their enjoyment of the sunshine: ‘I think you need all the sunshine you can get, because after all, it’s medicine.’

Several residents emphasised that being outdoors also entailed being active and in the company of others: ‘Outdoors I’m kind of more active and talk more and so on.’

‘Now that I’m at the nursing home, the thing is to get out and get some fresh air and meet other people.’

Recalling contact with one’s roots and identity

This theme was related to how identity and stories set against the natural surroundings of childhood and adolescence were linked to being rooted in the landscape, remembering your life history and being the person you are. The longing for the landscape of childhood was central: ‘If I could only go back and see the ocean now and again. I miss that here.’

‘Seeing the ocean is like experiencing tranquillity and finding your place.’

Some of the residents also related how their memories of nature helped them to remember their own life history: ‘I bought climbing boots and climbed all the way up Galdhøpiggen. Climbed to the very top, then I had a view of several countries.’

The residents might also say things that for them described sources of meaning: ‘That was kind of what life was all about, sitting outdoors picking [berries].’

Nature was also closely linked to the residents’ identity: ‘If you were born by the ocean, then you feel it’s something that lies in your blood.’

The photographs helped to bring back memories of natural landscapes and experiences of nature. ‘When we talk about it, I remember fishing trips, and I haven’t thought about fishing for several years.’

Experiencing old age in contact with nature

Experiencing old age in contact with nature was characterised by using nature differently than before, that the perception of nature was different, and that one’s relationship with nature had become different during the life course. They talked about functional impairment and tiredness, using expressions such as: ‘Then I was in good health and I went walking and things.’

‘I don’t miss the mountains now, I have a lot of difficulty walking. Hiking in the mountains was something I did earlier, when I was younger.’

The residents’ statements made it clear that when you can no longer move around on foot in the natural environment, your attitude to nature changes. Some of the utterances also showed signs of reconciliation with their own functional impairment and their determination to make the best of the situation: ‘Yes, now I don’t get out and about, so I simply have to sit here. Well, I have to face it with a smile.’

Several residents also found that their impaired senses meant that they could not hear the sounds of nature and birdsong. The course of nature and the changing seasons were also associated with their own life course: ‘It was green and lush with flowers, but when autumn comes, they wither one by one [said in a sad tone of voice].’

Discussion

The interviews gave the overall impression that the residents had made active use of the natural environment where they had lived earlier, and that contact with nature offered them joy, meaningful experiences and activities, and fellowship with others. The findings suggest that their relationship with nature had become somewhat different in old age, and indicated that their roots, identity and good memories were closely linked to experiences and a life lived in nature and the outdoor environment.

The findings referring to involvement and activity are interesting in light of the findings of other studies that have reported that elderly people stress the importance of having days filled with meaning at the nursing home (23). Moreover, good sensory experiences and variation in everyday life are reported to be essential (16), and the outdoor environment and nature may significantly influence the quality of life of elderly people (4).

Passivity led to discontent

Studies that report that the outdoor surroundings promote physical and mental well-being (16, 24, 25) also confirm our findings, in particular that passivity is reported as being a major problem for nursing home residents (26). The residents mostly appreciated being outdoors. They expressed their discontent with a passive and sedentary life indoors.

These findings further underline the importance of nursing homes actively utilising the outdoor environment, since inactivity rather than the ageing process has most impact on functional impairment and the ability to take care of oneself (27). The residents’ voices in this study contrast with reported findings that nursing home staff have low expectations of residents’ ability and willingness to take part in activities (28). Our findings are more in line with Day et al. (29) who reported contact with nature and the outdoor environment can strengthen the feeling of having good health, and help to mitigate the sense of functional impairment.

We consider that both the categories and individual statements in the study suggest that the elderly expressed the view that being outdoors and experiencing a change of environment led to both fascination with the surroundings (19) and relief from stress, worries and negative thoughts (30). This concurs with ART and research reporting that environments that provide relief from stress and tiredness are important in the care of the elderly (7).

Important social arenas

Nature and the outdoor environment were also important social arenas. This finding is in accordance with Kearney and Winterbottom (24), who reported that meeting others is one of several reasons why nursing home residents want to be outdoors. Furthermore, Bengtsson and Carlsson (16) wrote that outdoor areas facilitate a variety of ways of being together with other people.

Research reporting that the natural environment helps to promote social interaction as a source of restitution (30), and that staff find that sensory gardens encourage communication and strengthen social interaction (9), also supports these findings. Interestingly, both the findings of our study and the studies mentioned stand in contrast to those of studies reporting that the staff spend the minimum amount of time facilitating social interaction among the nursing home residents (31, 32).

Our findings indicate that the residents had a sense of loss in relation to the place where they had their roots, their affiliation and their identity. Giuliani’s findings (33) that involuntary separation from places to which you are attached can lead to pain and despair, and entail an interruption in the continuity of the life course, also support our findings.

We found that using photographs strengthened recollections of good memories, stories and the feeling of identity, which is of considerable importance in geriatric care (34). Drageset, Normann and Elstad (35) emphasise that nursing home residents with dementia disorders also ‘appear strengthened’ when they relate recollections linked to nature experiences.

In various ways, the residents indicated that their relationship to nature and outdoor activities had become different in old age, and that fellowship and social interaction were more associated with being outdoors than previously. If this is interpreted as part of the process of adaptation in later years, the findings are in line with Bergland’s study (5), in which it is reported that elderly people adjust their expectations in line with the reality of their situation.

The findings can also be understood as a desire for more social activity and outdoor life than what they experience in their everyday lives in the nursing home. These are significant factors in enabling them to regard the nursing home as a real home (36). In addition, next of kin value these factors as important qualities in the nursing home (37).

Experiences linked to the connection between the life course and the course of nature can help to create meaning and support a sense of coherence and wholeness, as Takkinen and Ruoppila (38) have reported. These existential reflections can contribute to the important work of reflecting on peace and reconciliation when facing death, as Andersson, Halberg and Edberg (39) have described.

The study’s strengths and limitations

It is considered a strength of the study that we have conducted two interviews with eight residents in two different contexts, and that we have used photographs to elicit the residents’ memories. The outdoor interviews helped us to acquire good and spontaneous descriptions of here and now experiences. The use of photographs also allowed for activating reflections and memories of residents’ earlier lives in connection with nature, and they constituted a helpful tool as described by Chao et al. (20). The interviewer himself had a strong commitment and a close relationship with nature as well as considerable clinical experience with nursing home residents, which was also considered to strengthen the study.

Limitations of the study are that the interviewer was inexperienced, and that all the interviews were conducted prior to transcription and analysis (22).

Conclusion

When asking nursing home residents about their experiences and memories related to contact with nature, this study shows that they acquired a change of environment, beneficial sensory experiences, meaningful activities, social interaction and good memories. They also got in touch with feelings such as sadness at impaired functional ability and the loss of childhood landscapes and geographical affiliation. Conversations inspired by photographs of different kinds of landscape activated memories and stories linked to their roots and identity. The findings are in line with research and relevant theories.

Based on the findings, we recommend a practice that makes it easy for elderly people to spend time outdoors regularly. Moreover, we recommend that being outdoors is established as a regular and natural component of the therapeutic environment at nursing homes, based on the individual resident’s preferences and resources (40).

Research communities in this field are challenged to explore and describe further relations between ageing and experiences of the natural environment. In addition, research should address how experiencing nature on a regular basis can promote well-being, quality of life, improved functioning and greater satisfaction of the basic needs of elderly people. We also encourage researchers to identify similarities and differences between residents’ needs and wishes for good days at the nursing home and the staff’s expectations and priorities in the everyday life of the nursing home.

References

1. Rodiek K, Schwartz B. Introduction: The outdoors as a multifaceted resource for older adults. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2006;19(3–4):1–6.

2. Kearney A, Winterbottom D. Nearby nature and long-term care facility residents: Benefits and design recommendations. Journal of Housing For the Elderly. 2006;19(3–4):7–28.

3. Cutler LJ, Kane RA. As great as all outdoors: A study of outdoor spaces as a neglected resource for nursing home residents. Journal of Housing For the Elderly. 2006;19(3–4):29–48.

4. Sugiyama T, Thompson CW. Environmental support for outdoor activities and older people's quality of life. Journal of Housing For the Elderly. 2006;19(3–4):167–85.

5. Bergland Å, Kirkevold M. Thriving in nursing homes in Norway: contributing aspects described by residents. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43(6):681–91.

6. Orr N, Wagstaffe A, Briscoe S, Garside R. How do older people describe their sensory experiences of the natural world? A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. BMC Geriatrics. 2016;16(1). DOI: 10.1186/s12877-016-0288-0.

7. Ottosson J, Grahn P. Measures of restoration in geriatric care residences: The influence of nature on elderly people's power of concentration, blood pressure and pulse rate. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2006;19(3–4):227–56.

8. Gonzalez MT, Kirkevold M. Benefits of sensory garden and horticultural activities in dementia care: A modified scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(19–20): 2698–715.

9. Gonzalez MT, Kirkevold M. Clinical use of sensory gardens and outdoor environments in Norwegian nursing homes: A cross-sectional e-mail survey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2015;36(1):35–43.

10. Webster JD, Haight BK. Memory lane milestones: Progress in reminiscence definition and classification. In: Webster JD, Haight BK, eds. The art and science of reminiscing: Theory, research, methods, and applications. London: Taylor & Francis, 1995;273–86.

11. Webster JD, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Mapping the future of reminiscence: A conceptual guide for research and practice. Research on Aging. 2010;32(4):527–64.

12. Cappeliez P, O’Rourke N, Chaudhury H. Functions of reminiscence and mental health in later life. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9(4):295–301.

13. Chao JS-Y, Liu JH-Y, Wu JC-Y, Jin JS-F, Chu JT-L, Huang JT-S, et al. The effects of group reminiscence therapy on depression, self esteem, and life satisfaction of elderly nursing home residents. Journal of Nursing Research. 2006;14(1):36–45.

14. Burns A, Byrne J, Ballard C, Holmes C. Sensory stimulation in dementia. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2002;325(7376):1312–13.

15. MacDonald C. Back to the real sensory world our «care» has taken away. Research into the effects of multisensory stimulation. Journal of Dementia Care. 2002;10(1):33–6.

16. Bengtsson A, Carlsson G. Outdoor environments at three nursing homes – Qualitative interviews with residents and next of kin. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2013;12(3):393–400.

17. Ulrich RS. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In: Altman I, Wohlwill JF, eds. Human behavior and the environment. New York: Plenum; 1983; 88–125.

18. Ulrich RS. Visual landscapes and psychological well-being. Landscape Research. 1979;4(1):17–23.

19. Kaplan R, Kaplan S. The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

20. Chao SY, Chen CR, Liu HY, Clark MJ. Meet the real elders: Reminiscence links past and present. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(19):2647–53.

21. Kirkevold M, Bergland D. The quality of qualitative data: Issues to consider when interviewing participants who have difficulties providing detailed accounts of their experiences. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2007; 2(2):68–75.

22. Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2012;40(8):795–805.

23. Dybvik TK, Gjengedal E, Lykkeslet E. At the mercy of others – For better or worse. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2014;28(3):537–43.

24. Kearney AR, Winterbottom D. Nearby nature and long-term care facility residents. The role of the outdoors in residential environments for aging. New York: Routledge; 2005;7–28.

25. Reynolds L. A valued relationship with nature and its influence on the use of gardens by older adults living in residential care. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2016;30(3):295–311.

26. Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(7):875–81.

27. Bergland A. Fysisk aktivitet og trening gir størst gevinst for de eldste. In: Bondevik M, Nygaard HA, eds. Tverrfaglig geriatri. En innføring. 3. utg. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. 2012. s. 221–38.

28. Haugland BØ. Meningsfulle aktiviteter på sykehjemmet. Sykepleien Forskning. 2012;7(1):16–21. DOI: 10.4220/sykepleienf.2012.0030.

29. Day AM, Theurer JA, Dykstra AD, Doyle PC. Nature and the natural environment as health facilitators: The need to reconceptualize the ICF Environmental Factors. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2012;34(26):2281–90.

30. Ulrich RS. Effects of gardens on health outcomes: theory and research. In: Marcus CC, Barnes M, eds. Healing gardens therapeutic benefits and design recommendations. New York: Wiley; 1999. s. 27–86.

31. Mallidou AA, Cummings GG, Schalm C, Estabrooks CA. Health care aides use of time in a residential long-term care unit: A time and motion study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2013;50(9):1229–39.

32. Slettebø Å. Safe, but lonely: Living in a nursing home. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2008;28(1):22–5.

33. Giuliani MV. Theory of attachment and place attachment. Psychological theories for environmental issues. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company; 2003. s. 137–70.

34. Calnan M, Badcott D, Woolhead G. Dignity under threat? A study of the experiences of older people in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Health Services. 2006;36(2): 355–75.

35. Drageset I, Normann K, Elstad I. Personer med demenssykdom i sykehjem: Refleksjon over livet. Nordisk tidsskrift for helseforskning. 2013;9(1):50–66.

36. Rijnaard M, van Hoof J, Janssen B, Verbeek H, Pocornie W, Eijkelenboom A, et al. The factors influencing the sense of home in nursing homes: A Systematic review from the perspective of residents. Journal of Aging Research. 2016; Article ID 6143645.

37. Isola A, Backman K, Voutilainen P, Rautsiala T. Family members’ experiences of the quality of geriatric care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2003;17(4):399–408.

38. Takkinen S, Ruoppila I. Meaning in life in three samples of elderly persons with high cognitive functioning. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2001;53(1):51–73.

39. Andersson M, Hallberg IR, Edberg A-K. Old people receiving municipal care, their experiences of what constitutes a good life in the last phase of life: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45(6):818–28.

40. Gonzalez MT, Kirkevold M. Design characteristics of sensory gardens in Norwegian nursing homes: A cross-sectional e-mail survey. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2016;30(2):141–55.

Comments