Registered nurses’ experiences of working with suicidal patients

Summary

Background: Each year, approximately 650 people take their own lives in Norway. Registered nurses (RNs) have a key role in the care provided to patients admitted after a suicide attempt. RNs must be able to regulate their own emotions and emotional expressions, as well as balancing their own involvement and distance to ensure good care for suicidal patients. The emotional reactions experienced by RNs can lead to burnout, as well as a desire to stop working with suicidal patients.

Objective: To examine how registered nurses who work with suicidal patients are affected. We also wanted to examine the reactions experienced by RNs when working with patients at risk of suicide, how they perceived that they themselves were looked after, as well as what they learned.

Method: This is a qualitative study in which the data have been obtained from individual, semi-structured interviews. The informants are five RNs, three of whom were specialist nurses and two who were in the process of specialising.

Results: One of the main findings was that the RNs relied upon their own feelings in the form of gut instincts in interactions with patients for whom they were responsible. The RNs were exposed to intense impressions in their everyday working situation, in which their patients experienced hopelessness, existential pain, a lack of privacy and autonomy, and some actually took their own lives. Nevertheless, the RNs often decline offers of supervision.

Conclusion: The informants in this study used themselves and their own bodies as tools when assessing the risk of suicide. Furthermore, they developed a clinical eye and created arenas in which the patients could share vulnerable and oppressive feelings and thoughts. They also experienced moral stress, where informal collegial support was vital. They felt that there were inadequate opportunities for debriefing, guidance and increasing knowledge. This finding highlights the duty of the employer to facilitate the care of the staff, to prevent burnout and high staff turnover.

Cite the article

Haugen N, Nortvedt L. Registered nurses’ experiences of working with suicidal patients. Sykepleien Forskning. 2023;18(91895):e-91895. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2023.91895en

Introduction

Each year, approximately 650 people take their own lives in Norway (1). The experience of having a patient take their life or attempt suicide during a stay in a psychiatric ward will have an impact on most registered nurses (RNs) in their interactions with this patient group (2).

It is demanding to have responsibility for a patient that requires extra follow-up and, in some cases, tracking or continual observation (3). RNs have a key role in the care provided on the admission of patients, and can observe any changes in the patient’s condition on an ongoing basis during treatment (4).

However, RNs must be able to regulate their own emotions and emotional expressions, as well as balancing their own involvement and distance to provide good care for suicidal patients (5). Interactions with patients require that RNs are capable and have necessary knowledge about suicide and its dynamics (6). They must be capable of assessing and observing the patient concerned, as well as having interpersonal skills in dealing with suicidal patients (7).

Research shows that RNs who work with this patient group experience feelings such as anger, frustration, shame, guilt, fear, anxiety, panic, helplessness, depression, self-reproach (8), grief and emptiness (9), condemnation, inadequacy and fear of reprisals (10).

The emotional reactions can lead to burnout (11), as well as a desire to stop working with suicidal patients (12). In the case of some RNs, working with patients who display suicidal behaviour and carry out suicide attempts can, in addition, constitute a threat to their own professional identity (13).

Suicide and attempted suicide affect the practices and behaviour of the staff, and losing a patient affects RNs on both a professional and a personal level for a long time (14).

RNs who experience that one of their own patients attempts suicide or takes their own life will, in some cases, have the same need for therapy and support as the patient’s family (11).

Studies show that supervision and debriefing after a suicide or attempted suicide is key to preventing consequential injury that may result in sick leave (11). After losing a patient, the informal support of colleagues is essential (15). The work environment should be a place in which individuals can express their own feelings and reflections without being judged by others (16).

Furthermore, nursing education programmes should provide training in assessing suicide risk, as well as procedures for dealing with suicide. A conciliatory inner dialogue on suffering that entails going back and reconciling previous thoughts, feelings and memories with the present can be a key coping mechanism for RNs who experience patient suicide (12, 13).

Generally, it is the healthcare facility’s duty to enable staff to process emotional discomfort, to ensure that they can deal with the challenges surrounding suicide and continue to provide good care (17).

Studies have shown how RNs are affected and what measures may help them after a suicide. Nevertheless, we have little information about how RNs use and acquire knowledge, whether they accept offers of supervision, and what they believe is lacking.

Moreover, there is little research on RNs’ perceptions of how they are looked after when working with suicidal patients and how they carry these experiences with them into their future work. Against the backdrop of the downgrading of mental health care, the experiences and perspectives of RNs are central.

Objective of the study

The objective of the study was to examine how registered nurses are affected by their work with suicidal patients. We also wanted to examine the reactions experienced by RNs when working with suicidal patients, how they perceived that they themselves were looked after, as well as what they learned.

Method

Design

We used a qualitative exploratory design and conducted individual research interviews with RNs who work in mental health care.

Sample

The interviews were carried out in the period from September to November 2020. We interviewed a total of seven RNs, but two of the informants chose to withdraw after the interviews had taken place. One male and four female RNs participated in the study. Of these five, two were studying to become specialist mental health nurses, while three were qualified specialist nurses. They ranged in age from 24 to 62, with an average age of 44.

All of the informants who were interviewed work at the same hospital, but in different departments. The period of time that informants said they had worked with suicidal patients ranged from a couple of years up to several decades. We experienced data saturation related to the objective of the study.

Even though two of the informants chose to withdraw after the interviews had taken place, the data from the other five interviews was rich enough to proceed with the project.

Recruitment

We contacted the clinical directors at three hospitals in south eastern Norway to request access to the relevant field of work, and we received a positive response from one of the hospitals. All heads of departments at the hospital concerned received a request containing detailed information about the study, recruitment tips, a poster to hang up in the department and a deadline for submitting relevant candidates.

The heads of departments asked if there were any staff who would like to participate in the study, for example, at staff meetings and at morning meetings. Those who were interested were put in contact with the first author, who provided more detailed information. Then we contacted them to arrange a time to interview each individual informant.

Implementation and data collection

All of the informants wanted to be interviewed at the hospital where they worked. We used different interview rooms separate from the departments where they worked to protect informant confidentiality. The first author conducted all the interviews using a semi-structured interview guide, which was drawn up on the basis of previous research on the topic (4–18).

The interviewer started by asking questions about whether the informant could tell us about incidents involving patients who had been at risk of suicide over a period of time, or about patients who had taken their own lives. We then proceeded to ask the following main questions:

- How has having a patient at risk of suicide or losing a patient affected you as an RN and as a person?

- What type of follow-up did you receive?

- What kinds of reactions did or does this patient group arouse in you?

- What experiences will you take with you?

The interviews had a duration of between 46–121 minutes, with an average of 45 minutes. They were digitally recorded.

Analysis

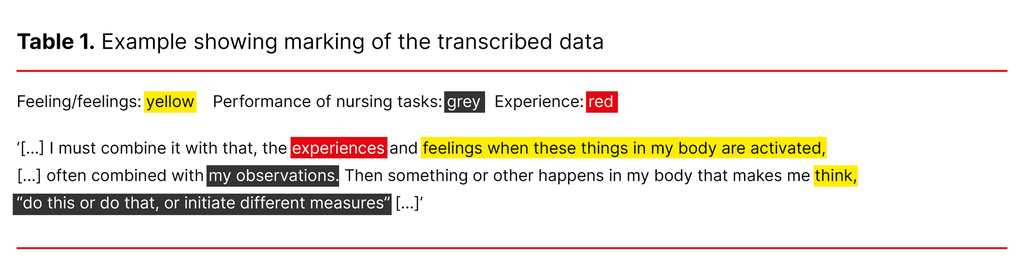

The first author transcribed the interviews after they were carried out, and both authors together used Malterud’s (19) four-step systematic text condensation of the data. The first step involved gaining an overall impression of the transcribed material by reading through the text several times, as we noted down ideas. Table 1 shows an example of an excerpt from the data provided by an informant with colour coding of the text.

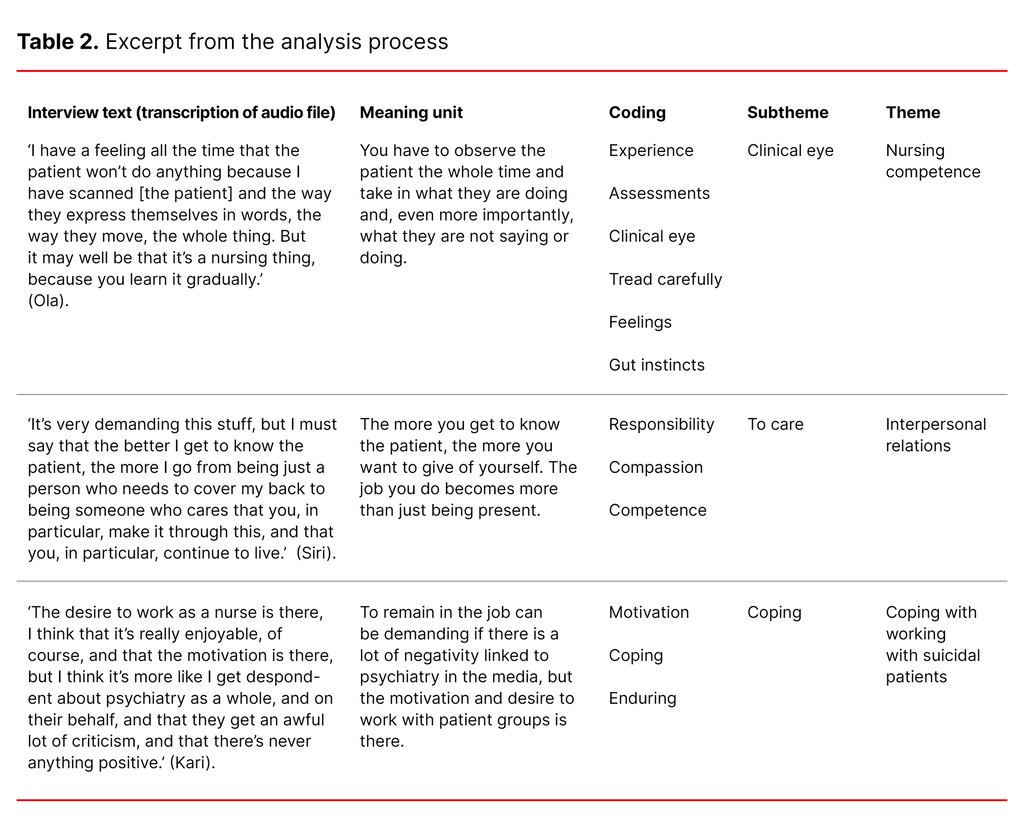

During step 2, meaning units were constructed (19). The first author cut and pasted text that carried independent meaning in relation to the research problem and questions. The third step involved the first author identifying codes and illustrative quotes. In the last part of the analysis, we reconstructed the material we had gone through; this is called ‘recontextualisation’ (19). Table 2 shows an excerpt from the analysis process.

Ethical considerations

The study was submitted to and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) (reference number 652737). The participants received oral and written information about the study. They were informed that participation was voluntary, and that they could withdraw if they wanted to without having to give a reason. We obtained written consent.

Confidentiality was protected by not conducting interviews at the individual’s place of work, and by storing the transcribed interviews on a password-protected PC in encrypted folders and deleting them after analysis had been carried out.

Anonymity was protected throughout the study by replacing names and contact details with codes and storing these in a name list that was kept separate from the rest of the data. Only the first author had access to this list.

The authors’ backgrounds and preconceptions

The first author worked as an RN within mental health care at the same health facility as the informants, but not in the same departments and she did not know the informants beforehand. The second author is an RN and associate professor. Both have specialist training in mental health care, which forms part of their preconceptions.

Results

Through analysis, the following themes emerged: 1) Nursing competence; 2) Interpersonal relations; and 3) Coping with working with suicidal patients. We have chosen to give the informants pseudonyms.

Nursing competence

The RNs told us that they paid attention to and relied on their own feelings and experiences. Combined with professional knowledge, they used themselves as tools in interactions with suicidal patients. One RN recounted the following:

‘I must combine it with that, the experiences and feelings when these things in my body are activated, [...] often combined with my observations. Then something or other happens in my body that makes me think, “do this or do that, or initiate different measures”.’ (Kari)

Kari claimed that in her interactions with patients, she used tools such as observation, as well as activating her own bodily knowledge and feelings. She further elaborated that she relied on research and literature in work with the patients, and claimed that ‘you yourself would be the ultimate tool in patient interaction’.

Several of the RNs mentioned ‘bodily activation’ in the form of vigilance, alertness or gut instinct, which they believed should not be ignored. One RN used the term ‘scanning’ to get an impression of whether he could trust a patient. He elaborated on the term thus:

‘I have a feeling all the time that the patient won’t do anything because I have scanned [the patient] and the way they express themselves in words, the way they move, the whole thing. But it may well be that it’s a nursing thing, because you learn it gradually.’ (Ola)

After the RN has scanned the patient, he gets an impression of how the patient is feeling, he takes in and observes body language, facial expressions, tone of voice and the words that are said.

A number of patients struggle with hopelessness. In this context, an RN recounted creating an alternative space:

‘Suicidal patients need privacy, they shouldn’t have someone hanging over them all the time, you shouldn’t talk to them all the time, so you can go back and forth because – it’s incredibly intense to be in that space, so much of nursing is about creating alternative spaces, or spaces to be in so that life is endurable there and then.’ (Siri)

In the alternative space, it is possible to give the patient faith that the treatment is working, even though it can seem invasive and you are divesting the patient of their autonomy. In addition, confidentiality and the use of humour were mentioned as key factors in milieu therapy with suicidal patients.

Interpersonal relations

All of the RNs emphasised the importance of colleagues and the support they received from those with whom they were on duty, with a low threshold for talking about uncertainty and challenging, terrible and positive experiences. One RN said:

‘What I take home with me is what my colleagues are struggling with. [...] I’ve put away what I’m struggling with.’ (Ola)

The RN told us that over several years in the profession, he had developed routines for dealing with what happens in the course of a shift. He no longer takes his patient experiences home with him, but rather what his colleagues are struggling with.

Another RN stressed that having detailed knowledge of each patient helped to establish a caring relationship, and that RNs give of themselves and are affected in a different way than they would otherwise be if they simply performed their duties in an instrumental manner:

‘It’s very demanding this stuff, but I must say that the better I get to know the patient, the more I go from being just a person who needs to cover my back to being someone who cares that you, in particular, make it through this, and that you, in particular, continue to live.’ (Siri)

The RNs felt that it was difficult to have responsibility for weighing up the options and making choices:

‘You have to make some tough decisions about priorities: “Shall I drop that nursing round and say that it must be postponed for half an hour or an hour?” and think that that’s how it will be this evening because I have to be here now. Or should you leave it be, prod it a bit and perhaps come back again, losing that thread [...].’ (Solveig)

The RNs were aware that they were there primarily for the patients. Nevertheless, it can be challenging to explain to patients why you are doing what you are doing since they are not familiar with everything that happens in a department.

Coping with working with suicidal patients

The RNs reported feeling that they would have liked more emphasis on knowledge development, supervision and debriefing, since working closely with people who are mentally ill affects them as nursing professionals. In addition, the RNs believed that they rarely sought supervision because their own experiences from challenging situations were not of sufficient importance for a supervision session, or because arrangements had not been made to enable them to have supervision.

Furthermore, they claimed that there was rarely or never an offer of a briefing or debriefing after a suicide attempt. Some of them had a guilty conscience and felt doubt, and had thoughts like ‘we should have prevented’ the suicide. One RN expressed it like this:

‘Mental illness is difficult. It’s so individual, and [to] sit and assess and see and save, thinking that everybody must be saved, everybody should have a chance to see hope in life.’ (Solveig)

For Solveig, the patients’ mental illnesses were challenging because they are personal, and because some patients cannot see any hope. Another RN also mentioned planting a seed of hope or carrying a patient’s hope for a few hours, even though it may have felt meaningless for some patients at the time.

When the job is perceived as rewarding, demanding and complex, one RN emphasised the following:

‘The desire to work as a nurse is there, I think that it’s really enjoyable, of course, and that the motivation is there, but I think it’s more like I get despondent about psychiatry as a whole, and on their behalf, and that they get an awful lot of criticism, and that there’s never anything positive.’ (Kari)

Furthermore, several informants pointed out that you cannot measure whether you are doing a satisfactory job, especially in relation to assessing suicide risks. They described uncertainty linked to whether a suicide could have been prevented, but at the same time, they had built up self assurance based on experience that helped them to make the right decisions.

One RN emphasised the importance of collegial support after a patient took their own life just after being transferred to another hospital. The consultant invited the RN to a review and reflection on whether they could have done anything differently. They concluded that ‘it was actually [the patient’s] choice, and the person concerned should be allowed to take ownership of that.’ (Siri)

Another RN also took up the issue of how to know if you are doing a good job in interactions with patients. Ola pointed out that he cannot do anything about the patient’s condition or situation, but to be able to say to yourself that ‘I had a good conversation with the patient’ makes it easier to continue in the profession.

Discussion

Coping with a demanding job

One of the main findings in the study was that the informants relied upon their own feelings in the form of gut instincts in interactions with patients for whom they were responsible. RNs develop a clinical eye (20) or intuition, while they also use knowledge built up on the basis of suicide risk assessments (21). However, finding a balance between trusting your own judgement and knowing when to ignore gut instincts is described as being difficult by our informants, especially for those who are newly qualified.

RNs must also be capable of holding conversations with patients without being emotionally overwhelmed. Moreover, RNs should not transfer what they are feeling, for example, in their interactions with patients (22), but strive to maintain a distance to their own experiences in patient interactions and behave like professionals (23).

Through working with suicidal patients, RNs gain an insight into the patients’ inner lives that the patient may not necessarily share with others. RNs should acknowledge the patient’s will to live or die (4) and, at the same time, attempt to understand the patient’s existential pain (7, 23).

The informants said that the work they do is not measured, while one RN found a sense of comfort and reward in conversations with the patients. Supervision is intended to provide an opportunity to get to know yourself, to develop on a professional and personal level and be able to reflect over your own practice (24).

However, RNs found that they did not have the opportunity to receive supervision, which could hinder them from working through their impressions and reactions. In order for RNs to maintain a belief in themselves as competent professionals (17), as well as to look after their own needs after a suicide (25), it should be a priority for employers to offer debriefing and supervision, in our opinion.

In addition, RNs should establish self preservation or coping strategies (26). It is possible that some of the RNs who have not established such strategies will react in the same way as patients’ families. When a crisis occurs, the sense of time will cease for some people, while others will experience a state in which they ‘freeze’ or experience affective stupor (27).

The consequences of working with suicidal patients manifest as bodily reactions, guilt feelings, anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms, according to the literature (8, 13–14, 18, 26). Moreover, Hofmann (28) claims that such work can threaten both physical and mental well-being, in addition to restricting reality.

Dyregrov (26) places emphasis on the need to practise or run through potential outcomes, as well as how one should react, in order to be able to respond to new crises in the best possible way. RNs also need to be reminded about the reactions that can arise after a crisis or traumatic event, and be given the opportunity to work through these together with colleagues (29).

Such follow-up can lead to increased solidarity and support, as well as enhancing understanding of their own reactions. Furthermore, it can make it easier to deal with future incidents (26).

The valuable collegial fellowship

The informants thought it was demanding to work with people who are mentally ill. However, they stressed that collegial fellowship was valuable in providing support and for working through challenging situations.

People who have experienced a crisis need to be met with consideration, understanding, respect and a safe environment (30). They must be given the opportunity to work through and deal with difficult emotions. Research also shows that, in particular, the informal support provided by colleagues, as well as the opportunity to vent feelings, is invaluable – especially when you have lost one of your patients to suicide (7, 8, 30).

Additionally, Wasserman (25) claims that the purpose of formal, emotional collegial support is to enhance RNs’ professional development by integrating newly attained knowledge after a suicide with previous knowledge and experience.

‘Moral stress’ is used in conjunction with RNs’ experiences with suicidal patients (17), which was also emphasised by our informants. It is understood to mean that what is expected of you is ethically demanding. For example, RNs may believe that taking your own life is wrong, but they also see how patients struggle to continue living. With increased demands for service user involvement, difficult dilemmas can arise at the time of discharge if service users disagree with therapists’ suggestions for further follow-up at home (31).

Making decisions that are contrary to the RNs’ values, thoughts and convictions can lead to exhaustion and burnout (29). In regard to retaining RNs in their positions, preventing burnout is key, by fostering a working environment that promotes reflection and consideration, as well as being given support by the management (32).

It is the duty of the workplace to help RNs and other personnel deal with work challenges in a healthy way, so that they can continue to provide good patient care. After a patient has taken their own life or attempted to do so, it is crucial that RNs have the opportunity to participate in debriefing, to enable them to regulate their own emotions and prevent feelings of guilt, shame and self-reproach (6, 10).

In addition, debriefing will help the organisation to gain an insight into the incident and be able to learn from it (14). In other words, employers must facilitate emotional and professional development in the form of immediate debriefing, as well as individual and group supervision. RNs must also be given training in suicide risk assessment, so that absenteeism and high staff turnover can be prevented (11).

This view is supported by Vråle and Drangsholt (24), who stress that supervision can contribute to increased ability to cope with the job, enhanced ability to deal with stress, as well as counteracting the feeling of being alone when making vital decisions. In this way, wear and tear and reduced work motivation can be countered. Organisations should also ensure that RNs have sufficient competence in supporting the families of patients in conjunction with a suicide or attempted suicide.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The informant group was relatively homogeneous, consisting of four women and one man. However, there was a good variation in age, ranging from people in their twenties up to those in their sixties. Some were beginning their careers while others were approaching the end of their working life. This indicated that the informants had very different and varied experience. Four of the informants were ethnic Norwegians while one came from another European country.

Two of the informants withdrew after the interviews had been carried out. However, these interviews did not bring anything more to light than the other interviews that were included. The number of informants was considered sufficient because we achieved saturation under way.

Furthermore, validity was enhanced by trying out the interview guide in two pilot interviews with nursing colleagues. The first author carried out the bulk of the work in the analysis process, while a reflexive approach was ensured throughout the entire research process by open discussion between the authors.

Conclusion

The informants in this study used themselves and their own bodies as tools when assessing the risk of suicide. Furthermore, they developed a clinical eye and created arenas in which the patients could share vulnerable and oppressive feelings and thoughts. They also experienced moral stress, in which informal collegial support was vital.

Nevertheless, they felt that their opportunities for debriefing, supervision and acquiring knowledge were inadequate. This highlights the employer’s duty to facilitate this kind of care for the staff to prevent burnout and high staff turnover.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0.

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments