Forensic nursing in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres

Registered nurses in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres participate in or perform all tasks in the emergency treatment of victims of sexual assault, including forensic tasks.

Background: Sexual assaults involve serious criminal actions that can result in great suffering and loss of health. Norwegian sexual assault reception centres offer holistic health services with an emphasis on medical tasks such as the treatment of injuries and the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy. They also offer psychosocial care and safeguard the legal perspective by means of forensic examination and documentation. This is provided by doctors and registered nurses. We have little knowledge of the tasks performed by the registered nurses, and what competence registered nurses in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres possess.

Objective: The objective of the study is to acquire knowledge about registered nurses’ competence and their performance of tasks in sexual assault reception centres.

Method: Online questionnaire surveys among staff at sexual assault reception centres in Norway.

Results: The study had a response rate of 50 per cent (n = 142). Registered nurses from all 24 sexual assault reception centres in Norway were represented. All were female and two out of three had more than 10 years’ work experience. One out of four registered nurses had completed a course in forensic medicine. In relation to forensic tasks such as collecting trace evidence on the surface of the body and oral cavity, three out of five registered nurses reported that they performed these actions independently or when the examining doctor delegated the tasks to them. No nurses reported collecting trace evidence from the genitalia or rectum independently or by delegation. Courses in clinical forensic medicine do not appear to impact on the registered nurses’ independence and delegated performance of forensic tasks. Registered nurses who had acquired competence through the basic course or the clinical course in forensic medicine or who had more than five years’ work experience in a sexual assault reception centre more often reported that they performed and documented psychosocial care and medical tasks either independently or when delegated to do so by the examining doctor, compared with those who did not possess such competence. Nine out of ten registered nurses wished to have greater competence.

Conclusion: Registered nurses in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres participate in or perform all tasks in the emergency treatment of sexual assault victims, including forensic tasks. Completing a course in forensic medicine appears to impact on the registered nurse’s role in psychosocial and medical tasks, but not in forensic tasks. The study shows that one out of four registered nurses wish to have a dedicated further education programme specialising in clinical forensic medicine.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), sexual assault is a widespread social problem that is found in all cultures and all levels of society worldwide (1, 2). Sexual assault involves serious criminal actions that can result in great suffering and loss of health for the victims (3).

In criminal law, sexual assault is sexual or indecent behaviour, sexual acts or sexual activity without informed consent (4, 5). In everyday language, different terms are used such as sexualised violence, rape and sexual assault, all of which include physical and/or mental violation of a person’s sexual integrity (6).

A 2014 Norwegian study reported that 9.4 per cent of women and 1.1 per cent of men had experienced rape at some point in their lives (7). In 2017, 2000 people attended Norway’s 24 sexual assault reception centres (8).

What does a forensic examination entail?

The victims of sexual assault need a holistic provision of health services, which includes emergency treatment of injuries, psychosocial care and the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy, in addition to forensic examination and documentation (2).

The aim of a forensic examination is to examine and document injuries and findings related to a criminal act. The victim’s body is ‘the crime scene’, and the examination must be performed as soon as possible and in a completely correct manner (9, 10). The work must be performed with a focus on high quality since the evidence may be decisive for the outcome of legal proceedings (9).

Services of the sexual assault reception centre

As a result of the need for a specialised service for sexual assault victims, Norway’s first rape reception centre was established in Oslo in 1986. In the Action Plan against Domestic Violence 2008–2011 – Turning Point, measures were outlined and funding provided for the establishment of reception centres for victims of sexual violence in all counties (11).

The sexual assault reception centres provide a 24-hour emergency service, regardless of whether the matter has been reported to the police, to anyone aged 14 or over (9, 12). The centres cater for all population groups and the number of cases varies from 7–552 annually.

There are considerable variations in the reception centres in relation to the form of organisation, service provision and quality of the forensic work (13). The specialist health service is responsible for ensuring that sexual assault victims are offered such services.

These services are provided at reception centres organised by Norwegian primary care emergency unit (primary health care services) as well as the gynaecology departments (specialist health service). The reception centres are mainly staffed by doctors and registered nurses (RNs) in part-time positions with different rota systems that entail them being present in person and/or being on call (13).

In Norway, most sexual assault reception centres work on the assumption that forensic work is traditionally regarded as being the remit of the doctor. The national documentation protocol and pre-packaged rape kits are adapted to this model.

In a few sexual assault reception centres, the RNs also have defined responsibilities and tasks in relation to the forensic work. The work of the reception centres is described in Guidelines IS1457: The sexual assault reception centre – guidelines for the health service (9).

The Health Personnel Act stipulates that health personnel must provide professional and compassionate care according to the situation in general, the nature of the work and their own qualifications (14). Health personnel are professionals. This means being competent – which is associated in turn with autonomy and professional qualifications (15).

Clinical forensic medicine in other countries

In Europe, clinical forensic medicine falls primarily within the professional sphere of doctors, but it is also emerging as a nursing specialisation (16, 17). In the USA and Canada, this is also a well-established professional work area for nurses.

Within forensic nursing, we find sexual assault nurse examiners (SANE) – a group of RNs with special competence in providing emergency treatment to the victims of sexual assault (18).

Clinical forensic medicine in Norway

In Norway, clinical forensic work is not a specialty for either doctors or nurses. There are no formal competence requirements for working in a sexual assault reception centre.

Competence enhancement in the field is based on short, individual courses arranged by the National Centre for Emergency Primary Health Care (NKLM).

The courses consist of a basic course for the staff of sexual assault reception centres that provides a general introduction to the various components of the emergency treatment provided, follow-up courses on different topics and a dedicated 3-day course on clinical forensic medicine related to sexual assault. Although the 3-day course is primarily for doctors, nurses can also apply.

Challenges linked to the quality of forensic work are pointed out in several reports (13, 19). NKLM states that the deficiencies in quality mean that there are no clear professional requirements in relation to personnel at the reception centres, and that ‘the challenges of establishing good forensic practice have been underestimated’ (19).

The guidelines give no clear recommendations in relation to responsibility and task distribution (9), nor is this clarified in the national protocol, which often acts as a guide to best forensic practice. The doctor is responsible, and the RNs’ work becomes almost ‘invisible’ in the forensic context.

No available Norwegian research describes current practices in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres in relation to task distribution and the performance of tasks in the provision of emergency treatment. Nor is there any research on what competence RNs in Norwegian reception centres possess.

The objective of the study

The objective of the study was to gain knowledge about RNs’ competence and performance of tasks in sexual assault reception centres as a basis for quality assuring and developing their competence within the provision of emergency treatment to assault victims.

Two research questions formed the point of departure for the study:

- What tasks in the overall provision of emergency treatment in the sexual assault reception centres do RNs participate in or perform?

- Are any of the following factors associated with whether RNs perform and document psychosocial, medical and forensic tasks independently or when delegated to them: number of years of work experience in sexual assault reception centres, further education, courses or organisation and size of the reception centre?

Method

Design

The study was a quantitative cross-sectional survey in the form of an online questionnaire.

Sample

The inclusion criteria were as follows: employed as an RN in one of the 24 sexual assault reception centres in Norway at the time of the survey.

Recruitment of respondents

We recruited respondents via the administrative manager at the sexual assault reception centre. The managers sent an email to RNs employed there with an information letter and a link to the questionnaire in Questback.

The data program ensured anonymity in that it was impossible to match the respondent’s email address or identity with the responses. Data collection took place in the period from 10 October 2017 to 1 December 2017.

Questionnaire

In a search of the literature, we could not find any previously developed questionnaires that were suitable for the survey. Therefore, we compiled a questionnaire, which was unvalidated, with the following topics: demographic data, psychosocial, medical and forensic tasks, self-reported competence and desired competence enhancement.

The electronic questionnaire contained 85 questions. The questionnaire was reviewed beforehand by three reception centre managers who assessed whether the questions were unambiguous and relevant. This assessment did not lead to any changes.

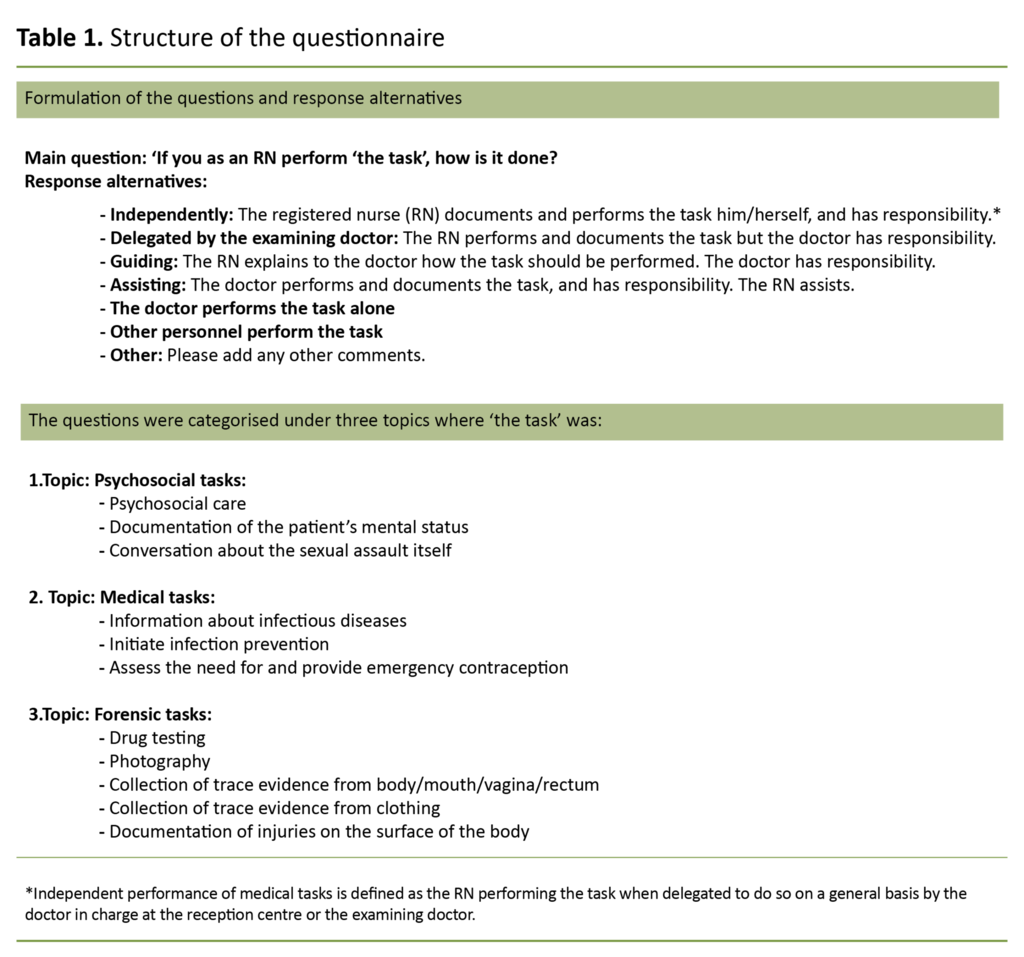

Table 1 shows the formulation of the main questions with alternative responses in the questionnaire. The questionnaire is too comprehensive to include as an appendix, but the first author can be contacted for more information.

The questions had mutually exclusive response alternatives, but a design error in the electronic questionnaire meant that the questions relating to psychosocial care and medical treatment were multiple choice.

When two alternative responses were given, the highest degree of independence was used, based on a descending order of importance: independent, delegated, guiding and assisting. Where the respondent had given three or more alternative responses, we categorised this as ‘Other’.

In addition, we asked the RNs whether they documented their own observations of the patient’s mental state, and if they marked and packed the trace evidence envelopes. The questions had yes/no response alternatives.

Analysis

The material is described with figures and percentages as well as the mean standard deviation (SD), median and range of the continuous variables.

We tested possible associations between the demographic and organisational variables and the RNs’ independent or delegated performance of tasks by using chi-squared tests. P-values were regarded as significant if they were below 0.05 (p < 0.05). All the analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25.

We divided the respondents into two groups in the analyses: one group consisted of those who reported that they performed and documented the task as an RN either independently or when delegated to do so by the examining doctor.

The other group consisted of those who reported that they had a guiding or assisting role in the tasks, or that a doctor or other health personnel performed the task.

Psychosocial tasks include care as well as conversations about the assault. During the emergency examination, the medical tasks include infection prevention and assessing the need for emergency contraception. Forensic tasks include drug testing, photography, collecting biological trace evidence from the surface of the body and mouth, and collecting trace evidence from clothing.

The sexual assault reception centres were categorised according to size and the number of sexual assaults in 2017 as follows: large reception centre: more than 100 cases, medium-sized reception centre: 40–99 cases, small reception centre: less than 40 cases.

In the analysis, the sexual assault reception centres were categorised according to whether the service was provided by the primary health care services or the specialist health service.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved on 26 June 2017 by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) (reference number 54683). Together with the request to participate, the informants received an information letter about voluntary participation and the right to withdraw from the study.

Answering the questionnaire was registered as consent to participating in the study. The data were anonymised and stored in a locked archive system.

Results

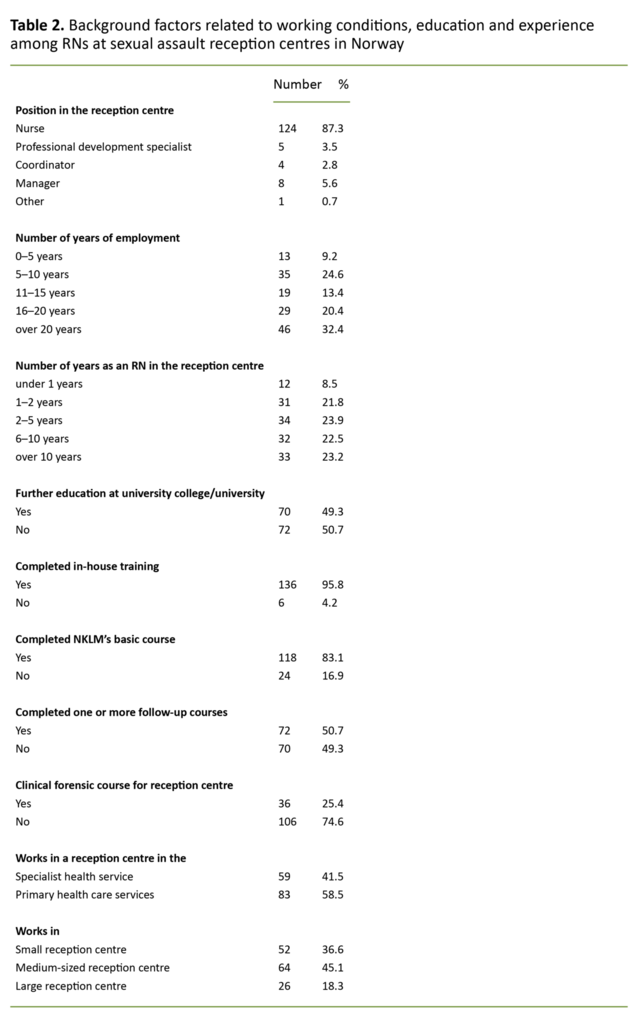

All the 24 sexual assault reception centres in Norway were represented. A total of 142 RNs out of 283 answered the questionnaire – a response rate of 50 per cent. All respondents were female RNs, and the mean age was 43.5 years (SD = 10.0).

The RNs stated that they had participated in from 0 to more than 300 emergency examinations, and the median was 20 examinations (mean 37, SD = 59.0).

The RNs stated that they had participated in from 0 to more than 300 emergency examinations.

Table 2 shows the RNs’ work experience, education and participation in relevant courses. A total of 58.5 of the nurses stated that they worked in the primary health care services, and 41.5 per cent in the specialist health service.

Some 36.6 per cent of the respondents worked in small reception centres (<40 cases), while 45.1 per cent worked in medium-sized reception centres (40–100 cases) and 18.3 per cent in large reception centres (>100 cases).

Performance of tasks in the emergency examination

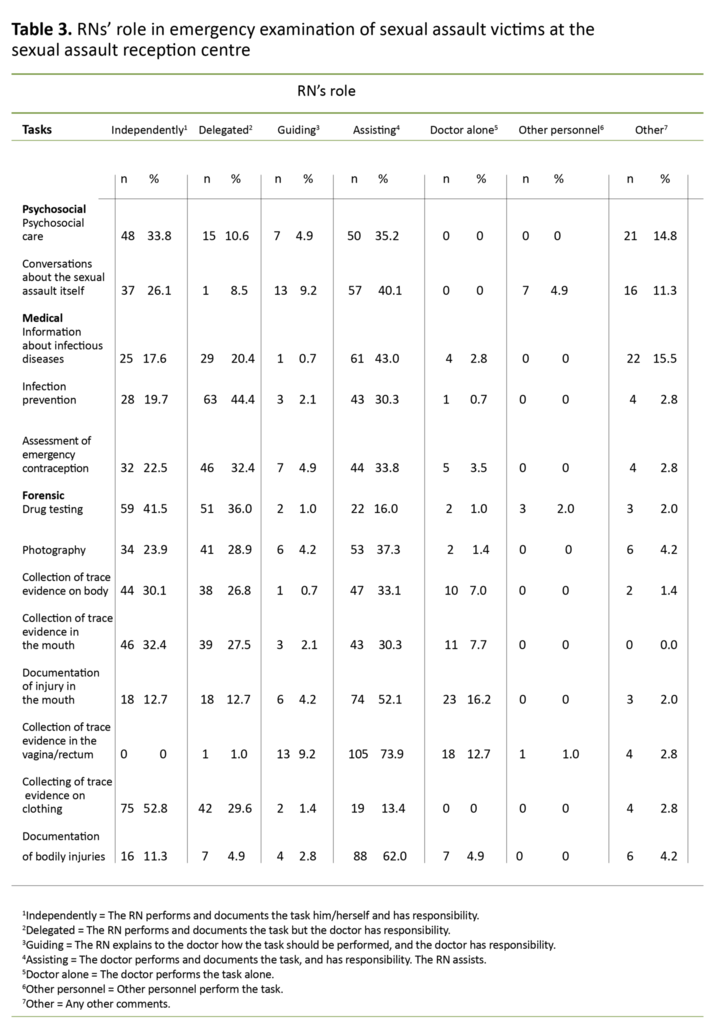

In relation to the tasks performed in the emergency examination, 33.8 per cent of the RNs reported that they carried out psychosocial care independently. The RNs reported collecting trace evidence from the surface of the body (30.1 per cent) and from the mouth (32.4 per cent) independently.

No one reported collecting trace evidence from the genitalia or rectum. When securing trace evidence from the genitalia or rectum, 9.0 per cent reported that they guided the doctor (Table 3).

Sixty-three per cent of the RNs documented their own observations of the patient’s mental health status. The RNs reported that they marked and packed the trace evidence envelopes after collecting trace evidence from the mouth (99.0 per cent) and from the surface of the body (100 per cent).

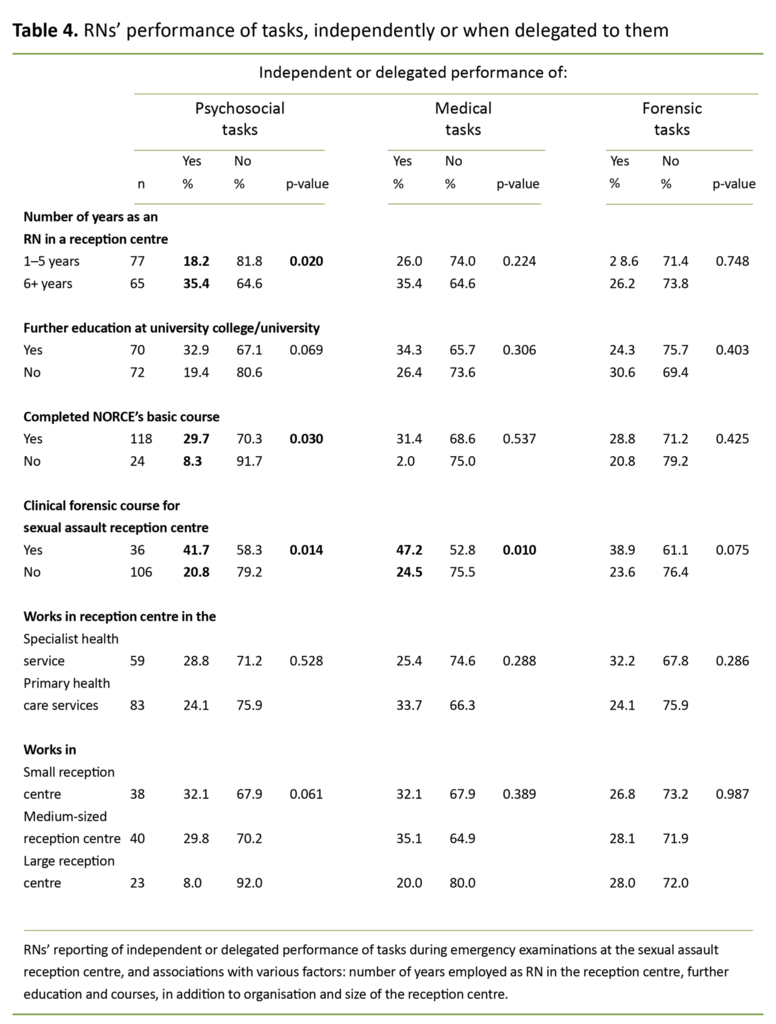

Courses in forensic medicine were associated with independent or delegated performance and documentation of psychosocial tasks (p = 0.014) and medical tasks (p = 0.010) (Table 3), but not forensic tasks.

More than five years’ work experience as an RN in the sexual assault reception centre was associated with performing and documenting psychosocial tasks independently or when delegated to do so (p = 0.020).

A higher percentage of those who had taken part in NKLM’s basic course performed and documented psychosocial tasks themselves, either independently or when delegated to do so (29.7 per cent), compared with those who had not participated in the course (8.3 per cent) (p = 0.030) (Table 4).

There were no significant differences between the RNs working in small and large sexual assault reception centres or between those working in reception centres in the primary health care services or specialist health service in relation to the degree of independence in how the tasks were performed.

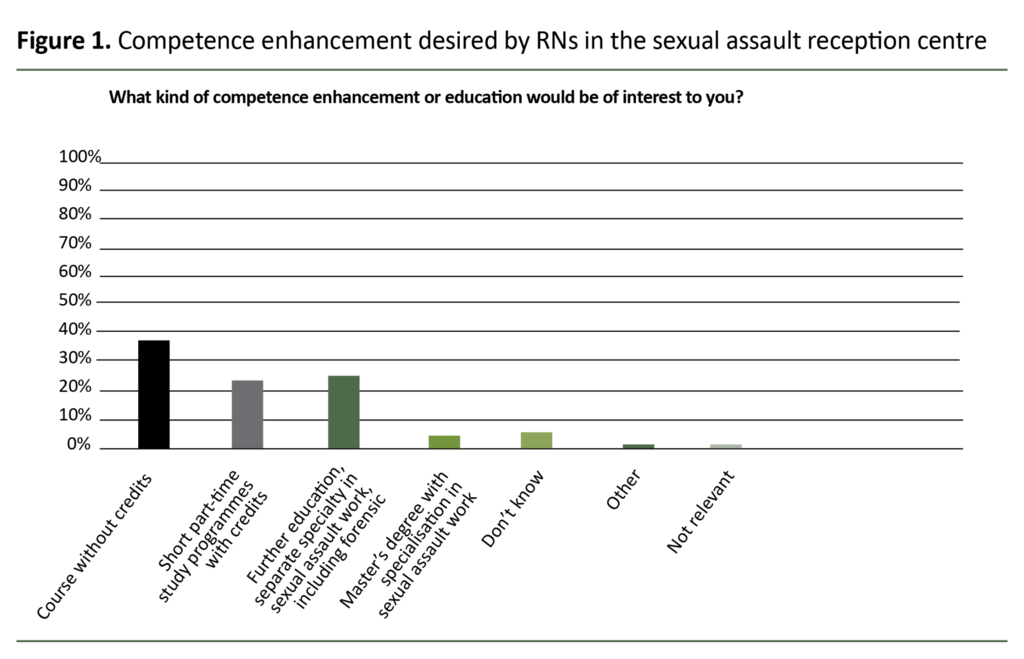

Of the RNs, 93 per cent reported that they wished to enhance their competence – 25.4 per cent wanted a dedicated further education programme specialising in clinical forensic work (Figure 1).

Discussion

RNs in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres participated in all kinds of tasks in the emergency treatment of sexual assault victims, including forensic work. The RNs reported a varying level of responsibility for the performance of the different tasks – from assisting the doctor to performing and documenting the tasks independently.

A higher percentage of those who had taken part in a clinical forensic course reported performing medical and psychosocial tasks independently or when delegated to do so.

However, participation in the course was not associated with performing forensic tasks. The study shows that most RNs at the sexual assault reception centres had extensive work experience, and half of them had further education.

Psychosocial care

Almost everyone in our study reported that they participated in the psychosocial care of the patient, but a smaller group (33.8 per cent) stated that they carried out this work independently. At the same time, the majority of RNs documented their own observations of the patient’s mental status (63.0 per cent).

Psychosocial care in different kinds of crises is covered in the bachelor’s degree, and is regarded as a nursing task. Our study shows no association between further education/a higher degree and the reporting of the independent or delegated performance of tasks.

Conversely, the study shows that the RNs who performed psychosocial tasks independently or when delegated to do so often had completed both the basic course and forensic course, and had more than five years’ work experience in sexual assault reception centres.

The competence of RNs may be of considerable significance in their interaction with the patient (20). Du Mont et al. assert that sexual assault victims state that the ability of health personnel to show respect, listen and believe their story is important (21).

Almost everyone reported that they participated in the psychosocial care of the patient.

The action plan against rape from the Ministry of Justice (2019–2022) points out that the prerequisite for good, holistic help is that health personnel have sufficient expertise (2). The findings in our study may indicate that specific competence can affect the performance of the RNs more than general competence.

The action plan states that the personnel at sexual assault reception centres must have the required competence but gives no detailed specification of the type of competence and/or measures for competence enhancement (2).

Conversations about the sexual assault are part of psychosocial care but are also an important part of the forensic examination, since this can be of decisive importance for the collection of adequate trace evidence and documentation of injuries (22, 23).

In legal proceedings, trace evidence and documentation of injuries alone cannot always decide the question of guilt. The patient’s mental and emotional state may be of decisive importance for the outcome of the criminal case (24).

Our study does not answer how RNs’ observations are used as a basis for the psychosocial care of the patients’ health or whether they are included in the forensic documentation. The findings highlight relevant issues linked to the performance and documentation of medical assistance that may also be important in a legal context.

Medical tasks

Prevention of infectious diseases and pregnancy is important for patients. This study shows that it was mostly RNs who gave information about and initiated infection prevention, and that the doctor rarely performed medical tasks on his/her own (0.7–3.5 per cent).

The questionnaire defined ‘independent performance of medical tasks’ as RNs performing the task when delegated to do so on a general basis by the doctor in charge at the reception centre or the examining doctor.

The findings are in line with the fact that initiating drugs treatment prescribed by a doctor is a standard nursing task.

An interesting finding is that there is a significant association between having participated in a forensic course and the RNs reporting that they performed medical tasks and documented these independently or when delegated to do so.

Our study does not elucidate the causal connection, but points out that specific competence also impacts on RNs’ performance of medical tasks.

In future development work, competence enhancement should be viewed in conjunction with the performance of tasks since RNs often carry out work to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy. A possible model is SANE education, which provides specialised knowledge about infection prevention and provides certification for the regulation of relevant medical treatment (18).

Forensic tasks

A forensic examination consists of various tasks, some of which require medical knowledge, while others are more closely linked to technical procedures such as trace evidence collection, including on clothing, and photography. Biological trace evidence can help to confirm or disprove the course of events and/or link a particular person to the assault (23, 24).

Almost all RNs reported that they participated in collecting trace evidence from the surface of the body and the oral cavity. In the case of the oral cavity, two-thirds of the RNs stated that they did this either independently (32.4 per cent) or when delegated to do so (27.5 per cent). No RNs reported that they themselves collected trace evidence from the genitalia or rectum.

Our study shows that RNs most often collect trace evidence from the oral cavity while the doctor collects trace evidence from the vagina and rectum. The study reveals a different approach to the oral cavity. This may be based on practical considerations, for example that the RN usually meets the patient first, and biological traces in the mouth swiftly disappear and must be secured before the patient can drink or brush their teeth (9, 22).

The traditional understanding of the tasks of doctors and RNs, and the fact that the trace evidence material is marked ‘Sampler: doctor’ may also impact on the RNs’ degree of independence in the performance of the tasks.

Examination of the vagina and rectum is a task that requires specific medical competence beyond trace evidence competence, since the patient must be examined for injury or disease concurrently with the trace evidence examination. In the Norwegian General Civil Penal Code, penile penetration of the mouth is placed on an equal footing with penile penetration of the vagina and rectum (4).

The requirement for correctly performed sampling, prevention of contamination, and packing and marking the sample material (9, 22) is the same for all orifices. Our study does not answer whether RNs’ performance of trace collection in the mouth is of lower quality than that of doctors.

This study shows that RNs perform trace collection in the oral cavity, which may be a significant factor for the legal outcome and determination of sentence, even though few of them have taken a forensic course (4, 25).

The findings in our study indicate that more knowledge is needed about how forensic work as a whole is practised in sexual assault reception centres, and that trace evidence material should be adapted to current practice.

Competence

This study shows that RNs perform forensic tasks that may be of decisive importance in the legal context. It is somewhat surprising to find that the course in forensic medicine does not appear to impact on the RNs independence and the delegation of forensic tasks, but on psychosocial and medical tasks.

The findings may be of significance for how we should view professional competence development in the discipline. The Health Personnel Act sees professional diligence in the context of competence (14).

When the specialist health service was given responsibility for the sexual assault reception centres, NKLM wrote in its professional recommendations that RNs have a key function in the reception centres and have poorer access to relevant courses than the doctors (19). Those performing the tasks must be given the opportunity to acquire relevant competence enhancement related to the tasks.

Almost all RNs wished to boost their competence.

In countries that have introduced forensic nursing in order to safeguard sexual assault victims, research reveals that this has had a positive effect on psychosocial care, medical treatment such as infection prevention, and not least the performance of forensic examinations and documentation (25, 26).

Almost all RNs (92.3 per cent) wished to boost their competence and half of them were interested in formalised competence enhancement in the form of higher education.

This is in line with international practice where forensic nursing has evolved from individual courses to formal qualifications with certification and/or higher education (18, 22).

Romain-Glassey (16) points out that the work of Swiss forensic RNs in connection with domestic violence follows in the footsteps of advanced clinical nursing at master’s degree level at several competence tiers.

Internationally, forensic nursing is a fast-growing field targeted at meeting society’s needs in the efforts to combat violence and assault (27). Standardised and systemised competence enhancement and educational pathways are key to boosting the quality of the service performed (28).

Strengths and limitations

A weakness of the study is that we used a self-developed, unvalidated questionnaire, and that the term ‘role’ is ambiguous and is only described in the introduction to the questionnaire. The formulation of questions may affect the respondents’ understanding, which may constitute a threat to validity (29).

The response rate of 50 per cent is acceptable in the methodology literature. However, this also means that we must be careful about generalising the findings (29, 30).

A strength of the study is that RNs from all sexual assault reception centres participated in the study, but it was not possible to test whether the participants were representative as regards demographic variables. The RNs’ perceptions of the topic’s relevance, their work situation, course participation or length of employment in the reception centre may have impacted on their participation and thus the results.

The first author is a nurse and heads the Vestfold sexual assault reception centre. Her experience and knowledge of the field have been crucial in designing and implementing this study. Conversely, her experiences may have affected the approach adopted and thus set limitations for the study (29).

Conclusion

RNs play a key role in Norwegian sexual assault reception centres. The RNs in the study participated in or performed all tasks in the provision of emergency treatment to sexual assault victims, including forensic tasks.

There was an association between the completion of a course in forensic medicine and the RN’s role in the performance of psychosocial and medical tasks but not in the performance of forensic tasks.

The RNs carried out forensic tasks that may be of importance in the legal context. The study showed that 9 out of 10 RNs wished to boost their competence in clinical forensic work.

The study raises relevant questions that can form the starting point of further research into competence enhancement for RNs and their role in the development of clinical forensic work vis-à-vis sexual assault victims.

References

1. World's Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for medico-legal care for victims of sexual violence. Genève: WHO; 2003. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42788/924154628X.pdf;jsessionid=6FDCD13422467D64BDF6E6D544F7F759?sequence=1 (downloaded 16.04.2020).

2. Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet. Handlingsplan mot voldtekt (2019–2022). Oslo: Justis- og beredskapsdepartement; 2019.

3. Kirkengen AL, Næss AB. Hvordan krenkede barn blir syke voksne. 3rd ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2015.

4. Lov 20. mai 2005 nr. 28 om straff (straffeloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2005-05-20-28/KAPITTEL_2-11#KAPITTEL_2-11 (downloaded 28.08.2019).

5. Store norske leksikon. Seksuelle overgrep. Store norske leksikon; 2019. Available at: https://snl.no/.search?query=seksuelle+overgrep (downloaded 06.09.2020).

6. Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for legevaktmedisin (NKLM). Seksualisert vold mot gutter og menn. Bergen: NKLM; 2017.

7. Thoresen S, Hjemdal OK. Vold og voldtekt i Norge. En nasjonal forekomststudie av vold i et livsløpsperspektiv. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress; 2014.

8. Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for legevaktmedisin. Årsmelding 2017. Bergen: Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for legevaktmedisin, Uni Research Helse; 2018. Report no. 1-2018. Available at: https://norce.s3.amazonaws.com/Nklm_%C3%85rsmelding_2017.pdf (downloaded 15.09.2020).

9. Sosial- og helsedirektoratet. Overgrepsmottak: Veileder for helsetjenesten. Oslo: Sosial- og helsedirektoratet; 2007.

10. Rognum TO, ed. Lærebok i rettsmedisin. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2016.

11. Justis- og politidepartementet. Vendepunkt: Handlingsplan mot vold i nære relasjoner 2008–2011. Oslo: Justis- og politidepartementet; 2007.

12. Det kongelige barne- og likestillingsdepartement. Opptrappingsplan mot vold og overgrep (2017–2021). Oslo: Det kongelige barne- og likestillingsdepartement; 2016–2017. Prop 12 S.

13. Eide AK, Fedreheim GE, Gjertsen H, Gustavsen A. «Det beste må ikke bli det godes fiende!» En evaluering av overgrepsmottakene. Bodø: Nordlandsforskning; 2012. Report no. 11/2012.

14. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 64 om helsepersonell m.v. (helsepersonelloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-64#KAPITTEL_2 (downloaded 14.12.2019).

15. Skau GM. Gode fagfolk vokser: Personlig kompetanse i arbeid med mennesker: Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2017.

16. Romain-Glassey N, Ninane F, de Puy J, Abt M, Mangin P, Morin D. The emergence of forensic nursing and advanced nursing practice in Switzerland: an innovative case Study Consultation. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2014;10(3):144–52.

17. Cowley R, Walsh E, Horrocks J. The role of the sexual assault nurse examiner in England: nurse experiences and perspectives. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2011;10(2):77–83.

18. International Association of Forensic Nurses. SANE, Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner: education guidelines 2018. Available at: https://www.forensicnurses.org/page/EducationGuidelines (downloaded 28.08.2019).

19. Johnsen GE, Hunskaar S, Alsaker K, Nesvold H. Overgrepsmottak 2017. Status etter spesialisthelsetjenestens ansvarsovertakelse. Bergen: Nasjonalt kompetansesenter for legevaktmedisin, Uni Research Helse; 2017.

20. Fehler-Cabral G, Campbell R, Patterson D. Adult sexual assault survivors' experiences with sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs). Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011:26(18);3618–39.

21. Du Mont J, Macdonald S, White M, Turner L, White D, Kaplan S, et al. Client satisfaction with nursing-led sexual assault and domestic violence services in Ontario. Journal of Forensic Nursing. 2014;10(3):122–34.

22. Lynch VA, Duval JB. Forensic nursing science. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2010.

23. Tozzo P, Ponzano E, Spigarolo G, Nespeca P, Caenazzo L. Collecting sexual assault history and forensic evidence from adult women in the emergency department: a retrospective study. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):383.

24. Politiet. Voldtektssituasjonen. Oslo: Kripos; 2014.

25. Dahl JY, Lomell HM. Fra spor til dom – en evaluering av DNA-reformen. Oslo: Politihøgskolen; 2013.

26. Campbell R, Patterson D, Lichty LF. The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs: a review of psychological, medical, legal, and community outcomes. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2005;6(4):313–29.

27. World's Health Organization (WHO). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women WHO clinical and policy guidelines 2013. Genève: WHO; 2013. Available at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241548595/en/ (downloaded 18.06.2019).

28. Simmons B. Graduate forensic nursing education: how to better educate nurses to care for this patient population. Nurse Educator. 2014;39(4):184–7.

29. Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2012.

30. Johannessen A, Christoffersen L, Tufte PA. Introduksjon til samfunnsvitenskapelig metode. 4th ed. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag, 2010.

Comments