Why do I stay in my job? A qualitative study on intensive care nurses’ working conditions

Summary

Background: Norway is facing a severe shortage of intensive care nurses, which became particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence suggests that the demand for intensive care nurses will continue to grow. Most research has focused on why intensive care nurses leave the profession, with an emphasis on the negative aspects of the job. However, many nurses are satisfied in their roles, and it is essential to understand which factors they consider important for remaining in the profession so these can be reinforced.

Objective: The objective of this study was to investigate the key attendance factors that impact on experienced intensive care nurses’ intention to remain in the profession.

Method: We conducted a qualitative study entailing nine individual, semi-structured interviews with intensive care nurses from three different intensive care units at St Olav’s Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital. The interviews were held in spring 2023. Participants had more than ten years of experience and worked in 70–100% positions. The data were analysed using systematic text condensation.

Results: The analysis resulted in six categories, grouped under three overarching themes: 1) ‘Meaning and variation’, describing intensive care nurses’ motivation in their daily work, highlighting that no two days are alike, as well as the sense of professional pride; 2) ‘A good working environment’, describing the importance of strong relationships with colleagues and supervisors for job satisfaction; and 3) ‘Professional engagement’, describing the need and opportunities for continuous development, as well as the significance of experience.

Conclusion: The study has deepened the understanding of key attendance factors that can support the retention of intensive care nurses. The main findings indicate that a good working environment, professional development and meaningful work are important for achieving a balance between job demands and control over the daily work. These findings can inform strategies at various levels of the health service to support the retention of intensive care nurses.

Cite the article

Krybelsrud S, Kamsvåg A, Mastad V, Gjeilo K. Why do I stay in my job? A qualitative study on intensive care nurses’ working conditions. Sykepleien Forskning. 2025;20(99714):e-99714. DOI: 10.4220/Sykepleienf.2025.99714en

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 highlighted the need for increased intensive care capacity and improved preparedness in Norwegian intensive care units (ICUs). The competence of intensive care nurses was also brought into focus (1–3). There is no official register of intensive care nurses in Norway, but Statistics Norway estimated that approximately 2500 were employed in the country in 2019 (4).

The demand for treatment of acutely and critically ill patients is steadily increasing, driven by demographic changes such as an ageing population, longer life expectancy and advances in medical technology that enable new treatment methods and improved access to care (5, 6).

The Health Personnel Commission’s report, ‘Time to Act’, highlights the challenges and conflicts facing healthcare services in light of these demographic shifts and the increasing demand for treatment. The report also outlined the need for greater specialisation in the health service and the challenges of ensuring an adequate and competent workforce (6).

Both nationally and internationally, efforts have been focussed on identifying measures to prevent future shortages of competence in intensive care nursing (2, 3). Many intensive care nurses do not anticipate working in intensive care until retirement age (7).

Hospitals not only struggle to retain intensive care nurses, but also to recruit new ones (6, 8). However, there is no large reserve of intensive care nurses, as many are already employed in other positions within the health sector, such as professional development and quality assurance (9).

Intensive care nursing is one of the occupational groups in Norwegian hospitals where staffing shortages are often addressed by hiring temporary agency staff, which is extremely costly for the health authorities (6).

When exploring what motivates employees to remain in the profession, the concept of ‘attendance factors’ is relevant. Attendance factors relate to the personal sense of meaning in the daily work, psychosocial elements that increase the likelihood of staying in a job, and aspects such as relationships with colleagues, interesting tasks and effective leadership (10, 11). Attendance factors contribute to employee retention and reduce absenteeism. The opposite are known as non-attendance factors.

We conducted a systematic literature search prior to the study, which showed that earlier studies have largely focused on the negative aspects of the profession, such as physical strain, stress, burnout and leaving the profession (intention to leave). Only a few studies have examined the factors that promote intensive care nurses’ job satisfaction and encourage them to remain in the profession (intention to stay) (12–20).

The studies described how the working environment and collaboration among intensive care nurses were important for job satisfaction (13–20). Research has shown that intensive care nurses who feel that their work is valued are more likely to remain in the profession. Being able to apply their own competence and experience in their work was also seen as meaningful (19, 20).

It was also considered important to be available to support people in vulnerable situations (16, 19). Other studies addressed the satisfaction that intensive care nurses derive from skills development (16). One study also showed a higher level of job satisfaction among intensive care nurses with more than ten years of experience compared to those with less experience (15).

None of the studies were conducted in a Scandinavian intensive care context, which is a significant limitation, as the organisation of hospital departments may differ and the role of the intensive care nurse varies. Moreover, the broader working conditions also differ considerably.

In order to maintain a high standard of care in the future, it is essential to retain intensive care nurses in the specialist health service (6).

Objective of the study

The lack of in-depth knowledge about attendance factors prompted us to investigate the factors that help retain experienced intensive care nurses in the profession. We based the study on the following research question:

‘What attendance factors do experienced intensive care nurses consider important for staying in the profession?’

Method

The study had a qualitative design. We followed the COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative research (21). The first two authors are newly qualified intensive care nurses, the third author is an experienced intensive care nurse and manager, and the last author is a researcher with no intensive care background.

Sample and data collection

In the period March–May 2023, we conducted nine semi-structured interviews with intensive care nurses from three ICUs at St Olav’s Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital. The inclusion criteria for participating in the study were patient-facing work as an intensive care nurse for at least ten years in a 70–100% position.

The participants had an average of 18.8 years of experience as intensive care nurses. Seven were female and two were male. Participants were recruited through email invitations sent to ICU managers and notices posted in staff rooms. All nurses who responded and wished to participate were included in the study. We first tested the interview guide with a pilot interview of an intensive care nurse who did not meet the inclusion criteria (Appendix 1 – only in Norwegian).

The interviews were conducted in a suitable room within the department, lasting an average of 28 minutes and were audio-recorded. They were transcribed immediately afterward. Data saturation was reached after eight interviews; however, one additional male participant was included to ensure gender diversity in the sample.

The first two authors conducted the interviews. They were familiar with several of the participants through student placements and work. The participants were therefore assigned such that none of the authors interviewed their own colleagues.

Analysis

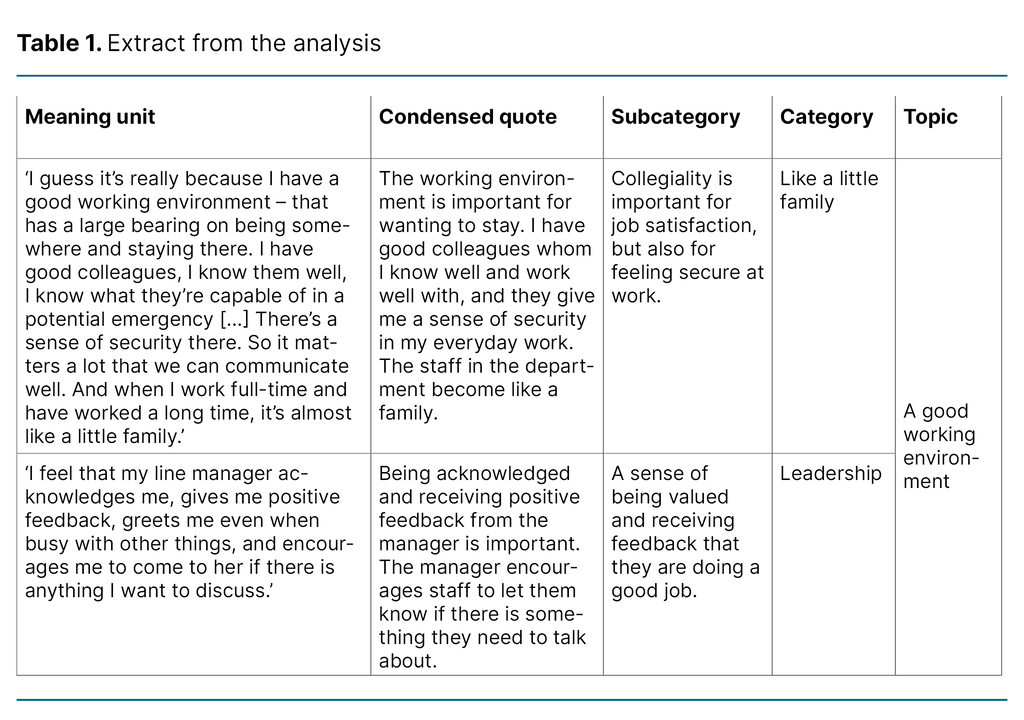

We analysed the interviews using systematic text condensation (22). The first authors conducted the analysis together. The data were analysed in four steps, with an additional fifth step added to obtain a comprehensive and refined overview of the categories (Table 1):

- We first read through the material to form an overall impression and identify preliminary codes.

- The preliminary codes were used as a basis when we reviewed the data again to identify meaning units, which were then sorted into code groups.

- We condensed and sorted the meaning units into subcategories within each code group.

- The condensed text was compiled into a results section, forming an analytical text. The subcategories were then arranged into categories.

- Finally, we grouped the categories into overarching themes.

Ethical considerations

Sikt – the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research was notified of the study (reference number 769705). We also applied to the clinics’ research committees and department heads to recruit participants for the study. The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) was responsible for the research in the study. We obtained written consent from all participants.

All data were treated confidentially and stored on a server at NTNU with two-step authentication. Data were anonymised in order to protect participants’ privacy, and we have not therefore given detailed descriptions of the participants.

Results

The analysis resulted in the following themes: Meaning and variation, A good working environment and Development and professional engagement.

Meaning and variation

Professional pride

All participants found it meaningful and rewarding to make a difference and to support patients in vulnerable situations, as well as their families. This was also important for job satisfaction. The intensive care nurses found it meaningful not only to see patients improving, but also to help ensure a dignified death when treatment was unsuccessful.

They found working with vulnerable people rewarding and considered their work to be beneficial to society. Participant 9 expressed it as follows: ‘If you find meaning in your work, you will stay.’

Several participants described many challenging situations in their work, but positive feedback on their efforts helped them cope with these situations. This contributed to a sense of professional pride among the intensive care nurses.

Varied workday

A varied workday was described as a valuable attendance factor. The intensive care nurses found challenges and unforeseen events stimulating. The diversity of patients, the complexity and the unpredictability of their working day were described as important factors for job satisfaction.

Participant 9 described the working days as follows: ‘Two patients can have the same diagnosis but behave in two completely different ways. That’s what makes being an intensive care nurse stimulating, absolutely.’

Having varied work tasks was seen as positive. Flexibility and working days that are never the same were considered important. Some participants expressed that working directly with intensive care patients and monitoring postoperative patients was the most stimulating part of the job. Others enjoyed shifts where they had no responsibility for their own patients, allowing them to assist wherever needed. The variation was a key factor in remaining in the profession, and fostered curiosity about the field.

Having control over their working day and the ability to contribute to decisions regarding their tasks was central to job satisfaction. A varied workload was also highlighted as an essential factor. Several participants described busy and demanding working days, but noted that quieter periods balanced out the hectic ones.

Participant 4 said: ‘It varies from day to day, week to week. Sometimes you have to work really hard, and other times there are slow days.’

Shift work was highlighted as a positive factor associated with a varied working day. It was crucial for the intensive care nurses to have input into their own shift rosters, which made shift work more manageable. Some preferred to avoid night shifts, while for others, aligning the roster with family life was important.

A good working environment

Like a little family

All the intensive care nurses highlighted supportive colleagues as one of the most central and valuable factors in their decision to remain in the profession. They described how a positive and supportive working environment contributed to job satisfaction and made working days more enjoyable. It helped them cope with stress during busy periods. They also mentioned a good working environment and a culture of mutual support.

The participants felt that they were good at looking out for each other. There was scope to support one another, both by asking for help and proactively offering to assist. The intensive care nurses also considered collaboration with other occupational groups to be meaningful and crucial for maintaining a good working environment.

They found it reassuring to have competent colleagues. Participant 4 described the collegial environment as follows: ‘And we have really good colleagues in my department, people work very intensely together, you know. It’s kind of like a family.’

Several participants said that social gatherings outside of work helped strengthen relationships. They felt closer to one another, which in turn improved collaboration at work. Good relationships were seen as crucial for feeling secure at work and helped them have constructive conversations after challenging situations. Participant 7 said: ‘My work colleagues, I really like them, actually.’

Leadership

Having a manager who is reassuring and invests in employees’ well-being at work was crucial for job satisfaction. The intensive care nurses felt it was important for managers to give feedback while also being open to receiving feedback. A manager who motivates staff and encourages them to discuss difficult issues was considered important.

It was essential for the nurses that managers view the employees as individuals and treat them as equals. Participant 7 said: ‘I feel that my line manager acknowledges me, gives me positive feedback, greets me even when busy with other things, and encourages me to come to her if there is anything I want to discuss.’

Development and professional engagement

Professional development

The intensive care nurses expressed that personal development in their profession was a priority. Several highlighted how the departments make considerable effort to hold professional development days and courses. The participants highlighted the importance of having the opportunity to keep their theoretical knowledge and practical skills up to date, so they can competently use medical-technical equipment and care for critically ill patients.

Participant 6 said: ‘Professional development is important. It helps maintain interest in the field and keeps our skills up to date.’

Several participants mentioned their curiosity and interest for the profession. Sustaining interest in the field and nurturing curiosity made the working day more rewarding and increased job satisfaction. Many also felt that a professional environment with clinical discussions among staff was both necessary and beneficial, and that they could learn a lot from colleagues and students.

Professional confidence

Experience and professional confidence in the field and in working with the patient group made the work less burdensome and was essential for remaining in the job. The intensive care nurses considered experience a contributing factor in achieving a sense of calm in the working day and retaining a sense of control. They described this as ‘coasting on experience’, meaning their accumulated knowledge allowed them to navigate the work more easily.

Their experience could also be used to support colleagues. The intensive care nurses found that supporting less experienced colleagues was both rewarding and motivating. Participant 2 said: ‘I’ve encountered so many different situations, and many people come to me with questions. I’ve had feedback such as, “It’s so helpful that you know this”, “It’s good that you’re here”, and things like that, [it] really boosts your motivation’.

this”, “It’s good that you’re here”, and things like that, [it] really boosts your motivation’.

Discussion

We identified several factors that are crucial for the retention of intensive care nurses in the long term. There was general consensus among the participants on which attendance factors were important.

Meaning and variation as motivators in the job

Our study showed that intensive care nurses found meaning and experienced professional pride in their daily work, which had a significant impact on job satisfaction. According to Nytrø (23), content and meaning in the daily work are ranked highly as important working environment factors.

Professional pride can be considered a key attendance factor for intensive care nurses. Several studies indicate that feeling valued by patients enhances nurses’ sense of professional pride and meaning in their work (16, 19, 20).

The findings also showed that having flexible and varied tasks is important. The intensive care nurses viewed shift work in a positive light, as it provided more variety in their daily routines. Our findings thus contrast with previous research, which shows that shift work is largely perceived as a negative aspect of the profession (24).

However, this positive attitude was contingent on having input into their own shift roster. Shift work can therefore be both an attendance factor and a non-attendance factor. This illustrates that the relationship between attendance factors and non-attendance factors is complicated and can vary between groups and individuals.

The complex interplay between attendance factors and non-attendance factors was also shown in a British study examining the relationship between intention to stay and intention to leave. The study showed that attendance factors did not necessarily prevent healthcare workers from leaving their jobs (25). The determining factor is the balance between non-attendance factors and attendance factors.

The intensive care nurses in our study regarded complex and unpredictable patients as a positive challenge. The tension helped prevent their daily work from becoming routine and boring. This finding aligns with research indicating that people who work with ICU patients enjoy challenging and fast-paced work (18, 20). Studies of attendance factors must therefore consider the characteristics of intensive care nursing.

Research shows that intensive care nurses are often exposed to stress and burnout, which can result in them leaving their jobs (26). Our findings indicate that intensive care nurses like variation in their workload, but this requires a balance between busy and quiet periods. Task variation contributes to job satisfaction, whereas monotonous tasks lead to boredom and dissatisfaction (27). Thus, variation can be seen as a buffer against occupational stress.

The importance of a good working environment and social support

Collegiality was highly valued by the intensive care nurses, who regarded fostering a good working environment as a shared responsibility. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which identify social support as one of the main factors for staff retention and job satisfaction (20, 27, 28).

Our study further shows that collegiality is essential for managing everyday work stress. This finding is supported by previous research, which indicates that social support mitigates the impact of high job demands. High turnover and workload pressures can lead to a poorer social environment and, consequently, a lack of social support (28).

Our findings also suggest that building good relationships with colleagues is often easier outside of work. Participation in social activities during leisure time enhances confidence and cohesion in the workplace. It is therefore important to initiate and facilitate such social gatherings.

Earlier research shows that a good working environment has a significant impact on job satisfaction (14, 20). One study found that colleagues working with critically ill patients experienced a greater degree of peer support than those in departments with less seriously ill patients (20). The participants described the same phenomenon as in our study: colleagues become like a family.

Our findings indicate that a supportive manager who actively involves staff is an important attendance factor for intensive care nurses and contributes to job satisfaction. Previous studies show that intensive care nurses’ relationship with their manager impacts on whether they remain in their jobs. Strong support from their manager is crucial (27, 29, 30). Our findings confirm this and highlight the importance of managers encouraging collaboration and supporting staff in their daily work.

Intensive care nurses’ professional engagement

For the participants in our study, professional development and curiosity about the field were essential for remaining in the job. Earlier research shows that opportunities for personal development can reduce perceived work pressure while simultaneously enhancing job satisfaction. This, in turn, improves the ability to manage constantly changing job demands, thereby contributing to staff retention in the profession (27, 28).

A lack of development opportunities is one of the reasons why intensive care nurses choose to resign. ICUs are characterised by rapid technological advances, requiring staff to continuously update and expand their skills (28, 31). This aligns with our findings, where intensive care nurses emphasised that staying abreast of theory and practice is crucial for effectively managing tasks and maintaining control over their work.

Balance between job demands and control

The intensive care nurses regarded extensive work experience as valuable, as it made their work feel less burdensome. Experience builds confidence and can enhance their sense of control in the daily work. Nursing is a profession characterised by high job demands and limited control over the daily work (32, 33). Low perceived control combined with high job demands has been shown to contribute to work-related stress (33).

Experience does not necessarily guarantee better control over the unpredictable nature of the work, but intensive care nurses with extensive experience probably manage it more effectively. A certain degree of flexibility in the work organisation and shift rosters can also enhance perceived control. Our findings are consistent with the principles of the demand–control model, a classical framework in occupational health research (23).

One of the model’s two hypotheses, the ‘buffer hypothesis,’ posits that employees with social support at work and control over their tasks can withstand high job demands. Both the model and our findings can be used to promote attendance factors among intensive care nurses. Our results also align with a recent study, which concluded that remaining in the profession depends on a complex interplay of multiple factors over time (34).

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study employed a qualitative design, allowing for a deeper exploration than previous questionnaire-based studies. New perspectives emerged, such as the significance of shift work and socialising with colleagues outside of work.

The study had clearly defined inclusion criteria, which enhances its validity. Although participants came from three different ICUs, they reported many of the same experiences. This suggests that the findings may be transferable to other ICUs. It may also have been a strength that we were familiar with some of the participants, as this facilitated recruitment.

Prior to the interviews, we developed an interview guide that was tested in a pilot interview. However, following the interviews, it became apparent that some questions could have been phrased differently to capture greater variation in the data. Another limitation is that the inclusion criteria may have excluded relevant participants who work fewer hours.

The interview and analysis process may have been influenced by our preunderstanding and interest in the topic, something we were conscious of and discussed both before and during the research process. However, we believe the authors’ different backgrounds and preunderstandings strengthen the credibility of the findings. We analysed and discussed the findings together, which perhaps enabled us to identify more nuances in the data than if we had analysed it individually (22).

The study is based on a thorough, systematic literature search. However, it is possible that we failed to identify relevant ‘grey literature’. We also cannot rule out the possibility that our familiarity with some of the participants led to information being withheld (35).

Conclusion

The study provides useful insights into attendance factors that may encourage experienced intensive care nurses to remain in the profession. The main findings highlight the importance of a good working environment, with strong relationships among colleagues and with managers. Professional development, extensive experience and a varied daily work routine, where nurses can contribute to decisions about their tasks, are also crucial.

The results can be used by managers and staff to maintain a balance between job demands, competence and control, and may also help improve nurses’ working day. Further research exploring attendance factors in greater depth is needed to develop targeted measures for retaining intensive care nurses in the profession.

Siw-Cathrin Krybelsrud and Ane Kamsvåg share first authorship.

The auhtors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open access CC BY 4.0

The Study's Contribution of New Knowledge

Comments